Abstract

Background

Vitiligo is an autoimmune disease of the skin with limited treatment options; there is an urgent need to identify and validate biomarkers of disease activity to support vitiligo clinical studies.

Objective

To investigate potential markers of disease activity directly in the skin of vitiligo subjects and healthy subjects.

Methods

Patient skin was sampled via a modified suction blister technique allowing for minimally invasive, objective assessment of cytokines and T cell infiltrates in interstitial skin fluid. Potential biomarkers were first defined and later validated in separate study groups.

Results

In screening and validation, CD8+ T cell number and CXCL9 protein concentration were significantly elevated in active lesional compared to non-lesional skin. CXCL9 protein concentration achieved greater sensitivity and specificity by ROC analysis. Suction blistering also allowed for phenotyping of the T cell infiltrate, which overwhelmingly expresses CXCR3.

Limitations

A small number of patients were enrolled for the study, including a single patient to define the treatment response.

Conclusion

Measuring CXCL9 directly in the skin may be effective in clinical trials as an early marker of treatment response. Additionally, use of the modified suction blister technique supports investigation of inflammatory skin diseases using powerful tools like flow cytometry and protein quantification.

Introduction

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune disease of the skin that causes disfiguring depigmented macules and patches1. Depigmentation is the result of CD8+ T cell-mediated killing of melanocytes, the pigment producing cells in the skin2. Phototherapy and topical immunosuppressants are used off label, with moderate results that require long treatment courses. Based on studies in our mouse model and human tissues3,4, we hypothesized that targeting the IFN-γ/CXCL10 axis could be an effective new treatment strategy for vitiligo5. Recent case reports revealed that JAK inhibitors, which block IFN-γ signaling, are effective at reversing vitiligo6,7, supporting our hypothesis. Clinical trials to test new, targeted treatments for vitiligo are on the horizon.

When conducting clinical trials in vitiligo, monitoring disease activity will be critical for measuring the treatment response. A common misconception is that biomarkers of treatment response are unnecessary, since the skin can be observed clinically; however, even the earliest clinical changes in vitiligo take 2-3 months to become apparent due to the time required for melanocyte precursors to proliferate, migrate, differentiate, and produce pigment. Measurable responses require 6 months or more, and current outcome measures are largely subjective and insensitive to small changes 8,9. Thus, relying only on observable changes in skin pigmentation is problematic.

Recent studies reported that serum levels of IFN-y-induced chemokines are elevated in patients with active vitiligo4,10 and correlate with treatment responses10. Serum chemokine levels, while reflecting general trends of disease activity in large cohorts, are likely too variable to serve as sensitive and specific markers of disease activity in a single patient. Moreover, patients with other autoimmune diseases exhibit increased inflammatory markers in the serum as well11,12, precluding their use as specific markers in vitiligo. Measuring markers directly in the skin could be a more sensitive and specific approach, however conventional analysis of skin through immunohistochemistry is problematic because lesions have low numbers of infiltrating T cells that are difficult to detect and quantify, unlike more inflammatory diseases. Thus, a more efficient method to sample vitiligo lesional skin and reliably measure treatment responses is needed.

We adapted a minimally invasive, non-scarring skin biopsy technique13-17 to reliably and accurately sample vitiligo lesions by inducing suction blisters, which provide blister fluid (consisting of interstitial skin fluid18) for analysis. Lesional blister fluid revealed an infiltrate of CD8+ T cells and CXCL9 protein that was both sensitive and specific for disease activity, in contrast to analysis of patient blood and serum. Suction blistering provides an opportunity to sample lesional skin in patients in a minimally invasive way, while yielding highly useful material to study markers of disease activity for translational studies and treatment responses in clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Subjects were recruited into two sequential groups for this study: The first to define markers of disease activity in vitiligo, and the second to independently validate these markers in a separate, non-overlapping group of subjects (Table 1). Inclusion/exclusion criteria were as follows: subjects with a diagnosis of vitiligo by clinical exam performed by a dermatologist and who were off treatment for at least 6 weeks were included in screening and validation groups. Subjects with recent onset of new lesions and objective clinical signs of activity, specifically confetti-like macules and/or trichrome lesions, were recruited to represent the “active” subgroup. Subjects with stable disease were selected based on their report of no recent change in their lesions and no objective clinical signs of disease activity (no confetti, trichrome, or inflammatory lesions and no koebner phenomenon). Those on treatment, with other inflammatory skin diseases, or presenting with the segmental subtype of vitiligo were excluded from the study. One subject was blistered repeatedly before and after starting treatment to define the treatment response.

Table 1.

Summary Demographic Information

| Active Vitiligo Defining Group |

Active Vitiligo Evaluation Group |

Stable Vitiligo Evaluation Group |

Healthy Controls Defining Group |

Healthy Controls Evaluation Group |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size, n |

8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 1 |

| Age, Mean (SD) y |

40.1 (9.2) | 46.3 (17.3) | 37.5 (7.2) | 29.8 (13.3) | 40 |

| Female, n (%) |

6 (75) | 6 (85.7) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (100.0) |

| Race n, (%) | |||||

| White | 5, (62.5) | 5, (62.5) | 4, (100.0) | 6, (75.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| Black | 2, (25.0) | 2, (25.0) | 0, (0.0) | 2, (25.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| Asian | 1, (12.5) | 1, (12.5) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Associated Autoimmune, n (%) |

0, (00.0) | 1, (12.5) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| FH Vitiligo, n (%) |

0, (0.0) | 1, (12.5) | 0, (0.0) | 1, (12.5) | 1 (100.0) |

| FH Other Autoimmune, n (%) |

0, (00.0) | 1, (12.5) | 0, (0.0) | 1, (12.5) | 0, (0.0) |

| Duration of Disease, Mean (SD) y |

19.6 (4.2) | 14.6 (16.1) | 19.3 (10.3) | N/A | N/A |

Age, sex, race, associated autoimmune disease, family history (FH) of vitiligo, FH of other autoimmune disease, and duration of disease are reported.

Suction blister skin biopsy and fluid aspiration was performed under IRB-approved protocols at UMMS and all samples were de-identified before use in experiments. Active vitiligo lesions were chosen based on a one-month history of new lesions and the presence of confetti-like depigmentation or trichrome lesions19,20. In stable subjects, selected sites were along the lesional edge with overlap between normal and depigmented skin. Non-lesional sites were selected as normal-appearing, non-depigmented skin when examined by Wood’s lamp, at least 5 cm from the nearest depigmented macule.

Blister Induction and Processing

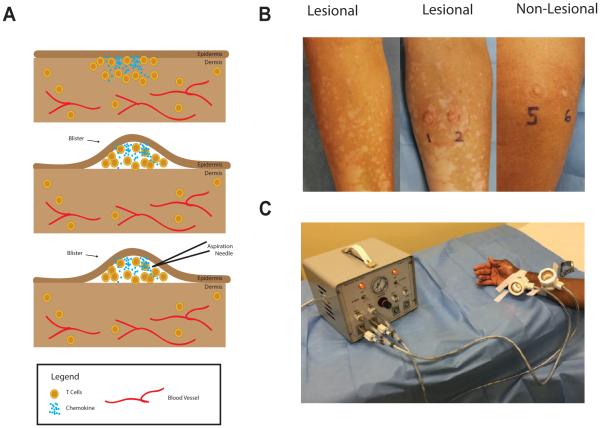

Suction blisters (1 cm in diameter) were induced on the skin using the Negative Pressure Instrument Model NP-4 (Electronic Diversities, Finksburg MD). The suction chambers were applied to the skin with 10-15 mm Hg of negative pressure and a constant temperature of 40°C; blisters formed between 30-60 minutes after initiation of the procedure. After blister formation, the blister fluid was aspirated through the roof using a 1 mL insulin syringe (Fig 1). Cells within the blister fluid were pelleted at 330×g for 10 minutes for cell staining and the supernatant was collected and frozen for future analysis by ELISA. Occasionally (9% of blisters) hemorrhage occurred in the blister, and these were excluded from analysis because the infiltrate more closely reflected that of the blood than the interstitial skin (data not shown).

Figure 1. Modified Suction Blister Technique.

The process of suction blistering the skin (A): T cells cluster near the epidermis, where the chemokine concentration is highest (top panel). After the suction blistering, the epidermis forms the roof of the blister and is separated from the dermis. T cells and chemokine at the site are present in the blister fluid and can be aspirated by fine needle aspiration. Representative photos of active vitiligo before blistering (left panel), the same site after blistering (middle panel), and a non-lesional site from the same patient (right panel) (B). A study subject waits while the suction blisters form (C).

ELISA and Flow Cytometry

According to manufacturer’s instructions, details in supplementary material.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software. Dual comparisons were made with the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for nonparametric data. Groups of three or more were analyzed by Kruskall-Wallis with Dunn’s post-tests for nonparametric data. Multiplicity adjusted p values from the Dunn’s post-tests are reported as post-test p values. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the sensitivity and specificity of tests performed on blister samples. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

T cell infiltrates are elevated in active vitiligo lesions

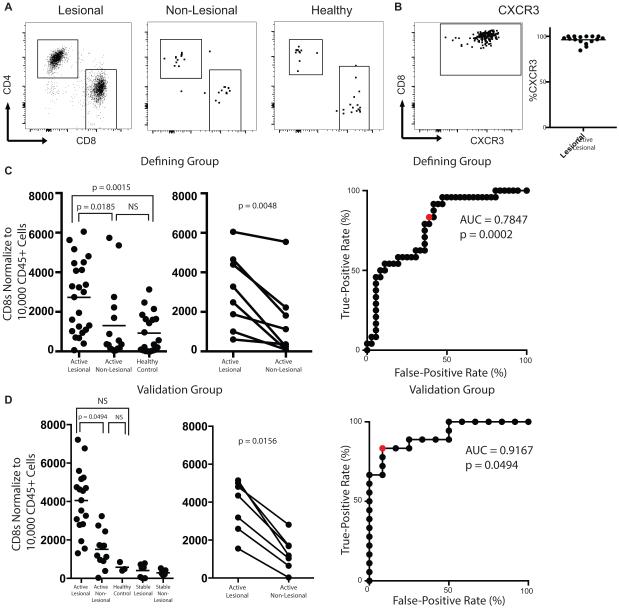

As CD8+ T recruitment to the skin is required for depigmentation4, we examined the T cell number in the skin as a potential biomarker for active disease. Flow cytometry of blister fluid in the screening group initially revealed that active lesional sites had a larger infiltrate of CD8+ T cells than non-lesional sites, or when compared to the skin of healthy individuals (Fig 2A and Supplementary Figure 1). We and others reported that skin-infiltrating CD8+ T cells express CXCR3, their receptor, when analyzed by IHC4,10,21. Here we found that CD8+ T cells uniformly express CXCR3 in the skin by flow cytometry (Fig 2B), supporting previous results.

Figure 2. CD8+ T cell Phenotyping and Quantification.

Representative flow plots of the T cell infiltrate isolated from lesional, non-lesional, and healthy control skin (A) and CXCR3 expression on CD8+ T cells in lesional skin (B). Quantification of the T cell infiltrate of each sample (left panels), paired analysis of vitiligo subjects (lesional vs non-lesional, right panels), and ROC curve for the Defining Group (C, D) and Validation group (E, F). Red dots mark threshold values described in the text.

We then sought to quantify the number of T cells in each blister. Lesional sites on average had a 2-fold increased infiltrate of CD8+ T cells with a mean of 2727 normalized cells to 1305 normalized cells in non-lesional skin (ANOVA all sites, p = 0.0009; t test lesional to non-lesional, post-test p = 0.0185; t test lesional to healthy, post-test p = 0.0015). There were no appreciable differences in infiltrates between non-lesional sites of active patients and healthy control skin (Fig 2C). We also found that total CD3+ T cell number is significantly higher in active lesional skin with an average difference of 1.4 fold (7651 Lesional, 5491 Non-Lesional p = 0.0015). Although CD4+ number in the skin was elevated in the defining group, comparisons did not reach statistical significance in the validation group or when the total data was compiled (Supplementary Figure 2). We then used a ROC analysis to test whether CD8+ T cell number could be used to predict disease activity and found it had reasonable predictive value (Fig 2D): a threshold of 1175 normalized CD8+ T cells achieved a sensitivity of 70% with specificity of 64%.

We next completed the same analyses in a second group of subjects to validate our observations and found similar results: lesional infiltrates contained significantly higher CD8+ T cells than in non-lesional sites (post-test p = 0.0494). This group also included four subjects with stable vitiligo, and T cell number in active vitiligo lesions was greater than that of stable lesional and stable non-lesional skin (post-test p < 0.0001 and post-test p < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig 2E). ROC analysis of this group revealed that a threshold of 2766 normalized CD8+ T cells yields 83% sensitivity and 92% specificity (Fig 2F).

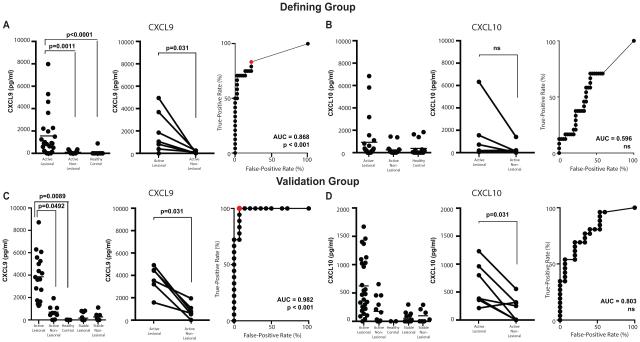

Skin CXCL9 protein is a more sensitive and specific marker of disease activity than CXCL10

We previously reported that CXCL9 and CXCL10 RNA transcripts were elevated in lesional skin of vitiligo patients4. CXCR3+ CD8+ T cells use CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 to traffic towards sites of inflammation22 and CXCL10 is functionally required for the progression and maintenance of vitiligo4. Using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), we found that CXCL9 was significantly elevated in lesional blister fluid compared to non-lesional skin and healthy controls and predicted disease activity better than CD8+ T cell numbers (Fig 3A). When we examined CXCL10 in the skin of vitiligo patients, we discovered it was not significantly higher in the active lesional skin and did not have good predictive value for disease activity (Fig 3B). When we evaluated CXCL9 as a candidate biomarker in the second validation group, we detected an average 5.5 fold difference between active lesional site and non-lesional skin (post-test p = 0.0492). ROC analysis suggests CXCL9 is a more sensitive and specific marker of disease activity than T cell number, achieving a threshold value of 1177 pg/mL with 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity (Fig 3C). We also evaluated CXCL10 in the skin of patients in the validation group and found similar results as the first group, although this time CXCL10 was 3.5 fold higher in lesional skin compared to non-lesional skin (post-test p = 0.0243). Despite detecting elevated levels of CXCL10 in active disease, these differences did not significantly increase the predictive value of CXCL10 (Fig 3D). In initial subjects, CXCL11 and IFN-γ were only detected at low levels if at all, and lesional levels of these chemokines were not elevated compared to non-lesional sites or healthy control skin despite having elevated CXCL9 and CXCL10 (Supplementary Fig 3). Thus, we did not measure these cytokines in the remaining subjects.

Figure 3. Chemokine Protein Levels in Blister Fluid.

Quantification of CXCL9 or CXCL10 in the blister fluid of the defining group (A and B, respectively) and validation group (C and D). Each panel is organized in the following manner: quantification by individual sample (left), paired analysis of vitiligo subjects (lesional vs non-lesional blister, middle panel), and ROC curve (right). Red dots mark threshold values described in the text.

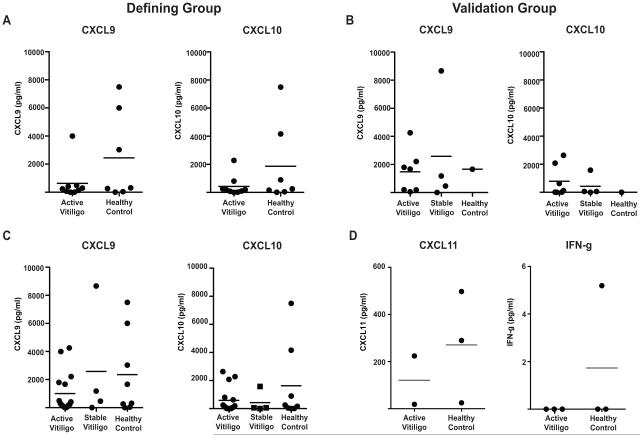

It was previously reported that serum CXCL9 and CXCL10 were significantly elevated in a large cohort of vitiligo patients compared to healthy controls and that upon intervention, the levels of CXCL10, but not CXCL9, experience a significant drop10. However we did not see a correlation between serum chemokines and disease activity in either cohort or in the total group when both cohorts were combined (Fig 4A-C), perhaps due to low sample size or our selection of patients with active disease phenotypes. Serum levels of CXCL11 and IFN-γ were either undetectable or not significantly different in sampled patients (Fig 4D).

Figure 4. Serum Chemokine Levels.

Serum levels of CXCL9 and CXCL10 are reported for the Defining Group (A) and the Validation Group (B). (C) Serum levels of CXCL9 (left) and CXCL10 (right) are compiled from both groups. (D) Serum levels of CXCL11 (left) and IFN-g (right).

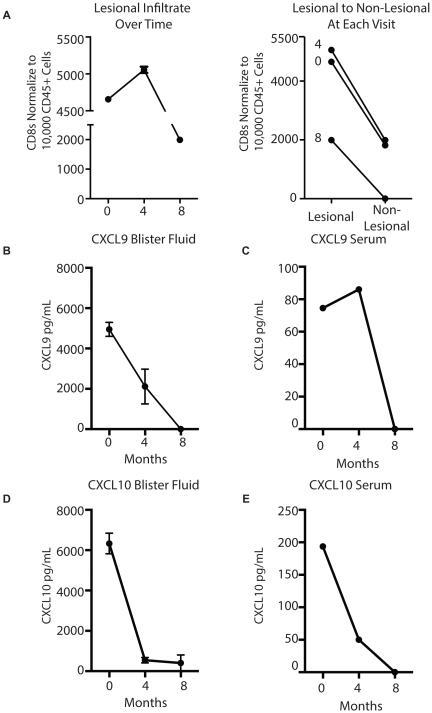

Case Study: CXCL9 protein is most responsive to multimodal treatment at an early time point

We followed one patient who was undergoing treatment for vitiligo using NB-UVB phototherapy and alternating topical tacrolimus and clobetasol. We sampled the same locations where the patient exhibited confetti on the first visit and at each subsequent visit. After the first four months, the patient reported inconsistent use of treatment, and no treatment for the previous 4 weeks. At this time, her T cell number remained largely unchanged, yet after an additional four months of consistent phototherapy and tacrolimus use, CD8+ T number declined 2-fold. However the non-lesional CD8+ T cell count also decreased, such that the lesional to non-lesional ratio remained unchanged (Fig 5A). Interestingly, lesional CXCL9 was decreased at the 2nd visit and undetectable at the 3rd visit (Fig 5B). Serum CXCL9 was undetectable at the final visit as well (Fig 5C). Lesional and serum CXCL10 was decreased at both visits (Fig 5C and 5D).

Figure 5. Case Study: Biomarkers Following Conventional Treatment.

Subject began inconsistent treatment at month 0, and then consistent treatment at the second visit, month 4. (A) T cells and chemokine protein reported at each visit (left panel). Representative slopes comparing lesional infiltrate to non-lesional infiltrate (right panel). (B,C) CXCL9 concentration measured in the blister fluid (B) and serum (C) at each visit. (D,E) CXCL10 concentration in the blister fluid (D) and serum (E) at each visit.

Discussion

We adapted a modified suction blister protocol to sample lesional skin from vitiligo patients and address the need for markers of disease activity and early treatment response. Our testing of potential biomarkers was founded upon observations made in our mouse model of vitiligo and in vitiligo patients. Thus, this work was hypothesis directed rather than a screen of multiple unrelated parameters. While both CD8+ T cell number and CXCL9 in the blister fluid demonstrated good predictive value in identifying those with active disease, CXCL9 had better sensitivity and specificity, and CXCL10 correlated only weakly.

In contrast to previous studies4,10, we could not use serum chemokine levels to distinguish those with active disease from those with stable disease or even healthy controls. This may be due to the small number of subjects enrolled in this study compared to other studies, or may be due to patient selection for this study (highly active confetti or trichrome patterns). Either way, it highlights the limitations of using serum markers to reliably measure disease activity in individual patients, and the advantage of skin-specific analyses.

Our results also indicate that blister fluid CD8+ T cell infiltration and CXCL9 protein are not induced by the blistering process itself, since non-lesional sites showed minimal levels of both. CXCL10 was elevated in the non-lesional skin of some subjects, which could be partially from blister trauma and might explain why it is a less specific marker using this method. Alternatively, CXCL9 protein may be more bioavailable for detection by ELISA than CXCL10 in blister fluid based on their different spatial and temporal expression in the skin23, binding affinities to structural elements24,25, and/or oligomerization within tissues26. We previously reported that both CXCL9 and CXCL10 had functional roles in our mouse model of vitiligo, however only CXCL10-deficient mice were protected from clinical disease4. Although both chemokines are expressed in active disease, they are produced by different cell types and with different kinetics during vitiligo progression23. CXCL9 is expressed earliest in murine vitiligo lesions and may be a more specific marker of disease activity23.

These markers may provide important information to support clinical trials: 1) to efficiently identify and enroll subjects with active IFN-γ-specific inflammation; 2) to reveal early treatment responses and drug efficacy; and 3) to improve the sensitivity of current, subjective outcomes measures. Future studies will further characterize these markers and their sensitivity to change following treatment in a larger patient cohort, where subgroup analysis based on disease variants or subject demographics could provide additional clues for categorizing vitiligo. Future studies could assess the effects of sun exposure on these parameters; our data was gathered primarily in the colder months in the Northeast, where sun exposure is less intense. Finally, this modified suction blister technique provides an unparalleled opportunity to sample lesions in patients with other inflammatory skin diseases to study the natural history of these diseases and their treatment responses.

Supplementary Material

Capsule Summary.

Suction blistering is a minimally invasive method to measure immune biomarkers directly in the skin

CXCL9 protein concentration and CD8+ T cell number in blister fluid are sensitive and specific biomarkers of active disease in vitiligo

These markers may support clinical trials in identifying active patients for enrollment as well as detecting early treatment responses

Acknowledgements

We thank our patients for their generous contribution of tissues, and Celia Hartigan and staff of the Clinical Research Center at UMMS (supported by award number UL1-TR001453, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH) for assistance with study subject appointments. Flow cytometry equipment is maintained by the UMMS Flow Cytometry Core Facility. JEH is supported by NIAMS, part of the NIH, under award number AR069114, and a Stiefel Scholar Award from the Dermatology Foundation. JMR is supported by a Research Grant and Calder Research Scholar Award from the American Skin Association.

Funding Sources:

JEH is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, part of the NIH, under award number AR069114, and a Stiefel Scholar Award from the Dermatology Foundation. JMR is supported by a Research Grant and Calder Research Scholar Award from the American Skin Association. This work was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1-TR001453.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: none declared

IRB: This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board (H-14848)

References

- 1.Dell'Anna ML, Hamzavi I, Harris J, Parsad D, Taieb A, Vitiligo Picardo M. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2015;1(1):1–16. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.11. EK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Boorn JG, Konijnenberg D, Dellemijn TA, et al. Autoimmune destruction of skin melanocytes by perilesional T cells from vitiligo patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(9):2220–2232. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris JE, Harris TH, Weninger W, Wherry EJ, Hunter CA, Turka LA. A mouse model of vitiligo with focused epidermal depigmentation requires IFN-gamma for autoreactive CD8(+) T-cell accumulation in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(7):1869–1876. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Richmond JM, et al. CXCL10 Is Critical for the Progression and Maintenance of Depigmentation in a Mouse Model of Vitiligo. Science translational medicine. 2014;6(223):223ra223. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashighi M, Harris JE. Interfering with the IFN-gamma/CXCL10 pathway to develop new targeted treatments for vitiligo. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(21):343. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.11.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JE, Rashighi M, Nguyen N, et al. Rapid skin repigmentation on oral ruxolitinib in a patient with coexistent vitiligo and alopecia areata (AA) Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016;74(2):370–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craiglow BG, King BA. Tofacitinib Citrate for the Treatment of Vitiligo: A Pathogenesis-Directed Therapy. JAMA dermatology. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komen L, da Graca V, Wolkerstorfer A, de Rie MA, Terwee CB, van der Veen JP. Vitiligo Area Scoring Index and Vitiligo European Task Force assessment: reliable and responsive instruments to measure the degree of depigmentation in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(2):437–443. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamzavi I, Jain H, McLean D, Shapiro J, Zeng H, Lui H. Parametric modeling of narrowband UV-B phototherapy for vitiligo using a novel quantitative tool: the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(6):677–683. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Wang Q, Wu J, et al. Increased Expression of CXCR3 and its Ligands in Vitiligo Patients and CXCL10 as a Potential Clinical Marker for Vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bjd.14416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotondi M, Falorni A, De Bellis A, et al. Elevated serum interferon-gamma-inducible chemokine-10/CXC chemokine ligand-10 in autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency and in vitro expression in human adrenal cells primary cultures after stimulation with proinflammatory cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):2357–2363. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Frascerra S, et al. Circulating chemokine (CXC motif) ligand (CXCL)9 is increased in aggressive chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, in association with CXCL10. Cytokine. 2011;55(2):288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caixia T, Hongwen F, Xiran L. Levels of soluble interleukin-2 receptor in the sera and skin tissue fluids of patients with vitiligo. Journal of dermatological science. 1999;21(1):59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(99)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anbar T, Zuel-Fakkar NM, Matta MF, Arbab MM. Elevated homocysteine levels in suction-induced blister fluid of active vitiligo lesions. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26(1):64–67. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2015.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozdemir M, Yillar G, Wolf R, et al. Increased basic fibroblast growth factor levels in serum and blister fluid from patients with vitiligo. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80(6):438–439. doi: 10.1080/000155500300012918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S, Jain VK, Saraswat PK. Suction blister epidermal grafting versus punch skin grafting in recalcitrant and stable vitiligo. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al] 1999;25(12):955–958. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.99069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babu A, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ. Punch grafting versus suction blister epidermal grafting in the treatment of stable lip vitiligo. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al] 2008;34(2):166–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34034.x. discussion 178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossing N, Worm AM. Interstitial fluid: exchange of macromolecules between plasma and skin interstitium. Clin Physiol. 1981;1(3):275–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1981.tb00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosa JJ, Currimbhoy SD, Ukoha U, et al. Confetti-like depigmentation: A potential sign of rapidly progressing vitiligo. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015;73(2):272–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hann SK, Kim YS, Yoo JH, Chun YS. Clinical and histopathologic characteristics of trichrome vitiligo. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2000;42(4):589–596. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertolotti A, Boniface K, Vergier B, et al. Type I interferon signature in the initiation of the immune response in vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27(3):398–407. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 in T cell function. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317(5):620–631. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richmond Jillian M., Essien Kingsley I, Currimbhoy Shraif D., Groom Joanna R., Pandya Amit G., Youd Michele E., Luster Andrew D., Harris John E. Keratinocyte-derived chemokines orchestrate T cell positioning in the epidermis during vitiligo and may serve as biomarkers of disease. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.09.016. DSB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mortier A, Van Damme J, Proost P. Overview of the mechanisms regulating chemokine activity and availability. Immunology letters. 2012;145(1-2):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao X, Moseman EA, Saito H, et al. Endothelial heparan sulfate controls chemokine presentation in recruitment of lymphocytes and dendritic cells to lymph nodes. Immunity. 2010;33(5):817–829. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campanella GS, Grimm J, Manice LA, et al. Oligomerization of CXCL10 is necessary for endothelial cell presentation and in vivo activity. J Immunol. 2006;177(10):6991–6998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.