Abstract

Purpose:

Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder caused by mutations in the α-galactosidase A gene. Migalastat, a pharmacological chaperone, binds to specific mutant forms of α-galactosidase A to restore lysosomal activity.

Methods:

A pharmacogenetic assay was used to identify the α-galactosidase A mutant forms amenable to migalastat. Six hundred Fabry disease–causing mutations were expressed in HEK-293 (HEK) cells; increases in α-galactosidase A activity were measured by a good laboratory practice (GLP)-validated assay (GLP HEK/Migalastat Amenability Assay). The predictive value of the assay was assessed based on pharmacodynamic responses to migalastat in phase II and III clinical studies.

Results:

Comparison of the GLP HEK assay results in in vivo white blood cell α-galactosidase A responses to migalastat in male patients showed high sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (≥0.875). GLP HEK assay results were also predictive of decreases in kidney globotriaosylceramide in males and plasma globotriaosylsphingosine in males and females. The clinical study subset of amenable mutations (n = 51) was representative of all 268 amenable mutations identified by the GLP HEK assay.

Conclusion:

The GLP HEK assay is a clinically validated method of identifying male and female Fabry patients for treatment with migalastat.

Genet Med 19 4, 430–438.

Keywords: enzyme replacement therapy, Fabry disease, lysosomal storage disorder, personalized medicine, pharmacological chaperone

Introduction

Fabry disease (MIM 301500) is a rare and progressive X-linked disorder that is due to deficiency of lysosomal α-galactosidase A (α-Gal A; MIM 300644, EC3.2.1.22).1 The accumulation of glycosphingolipid substrates leads to impairment of kidney, heart, and brain function and to early death.2

To date, more than 800 Fabry disease–associated mutations to the gene encoding α-Gal A (GLA) have been identified. Approximately 60% are missense mutations resulting in single amino acid substitutions in α-Gal A.2,3 Missense mutations result in heterogeneous phenotypes ranging from classic to nonclassic.4,5,6,7

Oral migalastat (1-deoxygalactonojirimycin, AT1001), a low-molecular-weight pharmacological chaperone, is being developed for Fabry disease as an alternative to intravenous enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). Migalastat binds to the active site of specific mutant forms of α-Gal A, thus stabilizing the enzyme and restoring trafficking to lysosomes where the enzyme can catabolize substrates.8,9,10,11

Certain patients with Fabry disease produce mutant forms of α-Gal A that are amenable to migalastat. These patients express mutant forms of α-Gal A that show increased total cellular α-Gal A activity after treatment with migalastat. These mutant forms are commonly single missense mutations in GLA,10,11,12,13 although some may be small in-frame insertions, deletions, or multiple-site missense mutations. Mutations in GLA that impair the synthesis of α-Gal A or severely affect protein structure (e.g., frameshift, truncation, large insertion or deletion mutations) and catalytic activity are expected to lead to mutant forms of α-Gal A that do not show increased cellular activity in response to migalastat.

Cell-based studies have shown that migalastat increases the levels of many different mutant forms of α-Gal A.11,14,15,16,17 The migalastat-mediated increases were consistent across different cell lines with the same mutation.11 The cell-based responses of 19 α-Gal A mutant forms to a clinically achievable concentration of migalastat (10 µmol/l) were generally consistent with observed increases in α-Gal A activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from male Fabry patients who were orally administered migalastat.16

Prior to the current study, only a small percentage of the approximately 800 GLA mutations that cause Fabry disease had been evaluated for their response to migalastat. These studies9,11,12,14,15,16,17 used different research-based assays with varying procedures, quality controls, and acceptance criteria. Many were conducted using patient-derived cells, fluids, or tissues. Samples derived from female patients present a challenge because the cells are a mixture that expresses either wild-type or mutant forms of α-Gal A.18 The measured α-Gal A activity in these cells is dominated by the wild-type enzyme, which is responsive to migalastat complicating the interpretation. Hence, neither the baseline activity nor the effect of migalastat on the mutant form can be accurately determined from cells from female Fabry patients.

In the current study, a good laboratory practice (GLP)-validated in vitro assay was used to express each of 600 primarily missense Fabry disease–causing mutations for testing in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK) cells and measuring increases in α-Gal A activity in response to migalastat. An amenable mutant form of α-Gal A in the GLP HEK (i.e., migalastat amenability) assay was defined by α-Gal A activity in the presence of 10 µmol/l migalastat that is ≥1.20-fold over baseline with an absolute increase of ≥3.0% wild-type α-Gal A activity. Clinical validation of the assay was assessed based on Fabry disease patient pharmacodynamic responses in phase II and III clinical studies. Seventy-three unique amenable and nonamenable mutations were represented in these studies.

Materials and Methods

Mutations that qualify for testing in the GLP-validated human embryonic kidney 293 cell in vitro assay

Fabry disease–causing GLA mutations that qualify for testing include missense mutations, nonsense mutations near the carboxyl terminus, small insertions and deletions that maintain reading frame, and complex mutations comprising two or more of these types of mutations on a single GLA allele.

Mutations that do not qualify for testing include large deletions, insertions, truncations, frameshift mutations, and splice-site mutations. These types of mutations grossly alter the structure and function of the enzyme and may result in complete loss of expression.

Mutations that do not qualify for testing in the GLP HEK assay are categorized as nonamenable (see the criteria for amenable mutation below).

Summary of the GLP HEK assay method

Qualifying Fabry disease–associated mutations were identified from the Human Gene Mutation Database (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac), the Shire Human Genetic Therapies Fabry Outcome Survey registry (https://www.fabryos.com; accessed on or before 30 June 2009), clinical studies with migalastat, and other public sources. Qualified mutations (total number: 600) were engineered into a mammalian expression vector (pcDNA6/v5-His A) containing the human α-Gal A cDNA (Supplementary Figure S1 online) as previously described.16

The resultant recombinant mutant, wild-type (WT), or vector pcDNA constructs underwent validated DNA quality-control assessments conducted in compliance with relevant GLP regulations. Plasmids meeting the prespecified DNA quality-acceptance criteria were used for transfection.

HEK-293 cells were seeded into 96-well plates, transfected with individual mutant GLA-containing DNA plasmids, and incubated in the presence or absence of 10 µmol/l migalastat for 5 days. Then, lysis buffer was added to obtain cell lysates, which were assayed for total protein and α-Gal A activity. Transfection efficiency was measured as the amount of GLA cDNA in the cell lysates detected by qPCR.

The α-Gal A activity in each cell lysate was measured using the fluorogenic substrate, 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-d-galactopyranoside, and normalized to the total protein. The endogenous α-Gal A activity, as measured in empty vector-transfected cell lysates, was subtracted from the activity in mutant or wild type–transfected cell lysates. The resultant activity for each α-Gal A mutant form, in the presence or absence of 10 µmol/l migalastat, was thereby obtained and used to determine its response to 10 µmol/l migalastat. See the Supplementary Material online for the detailed methodology.

Amenable mutation criteria

Mutant forms that qualified for testing in the GLP HEK assay and showed α-Gal A activity in the presence of 10 µmol/l migalastat that is ≥1.20-fold over baseline with an absolute increase of ≥3.0% wild-type α-Gal A activity (equations provided in Supplementary Material online) and their corresponding GLA mutations were categorized as amenable. The approximate average maximum concentration measured in the plasma of Fabry patients following a single oral administration of 150 mg migalastat HCl is 10 µmol/l.19 The 3.0% wild-type minimum absolute increase was based on literature indicating that increases of 1 to 5% of normal enzyme activity in vivo may be clinically meaningful.20,21 The 1.20-fold over baseline criterion was specified to require mutant forms with high baseline activity in vitro to demonstrate greater absolute increases than mutant forms with low or zero baseline activity.

Assessment of the clinical validation of the GLP HEK assay

Mutant α-Gal A responses to migalastat in the GLP HEK assay and in male Fabry patient–derived lymphoblast cell lines in vitro were compared.

Mutant α-Gal A responses to migalastat in the GLP HEK assay were compared with the pharmacodynamic effects of orally administered migalastat on:

α-Gal A levels in PBMCs isolated from male Fabry patients.

Mean number of globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) inclusions per kidney interstitial capillary in male Fabry patients.

Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) in male and female Fabry patients.

GLP HEK testing and amenability categorization of all 73 unique mutations from phase II22,23 and phase III clinical studies (unpublished data; ref. 24) and 455 other Fabry disease–associated mutations were completed prior to the availability of pharmacodynamic results from phase III studies.

The α-Gal A levels in PBMCs and lymphoblast cell lines were measured as previously described.11,16,22,23 The mean number of kidney GL-3 inclusions per interstitial capillary was determined.25 Plasma lyso-Gb3 was quantitatively analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy using a novel, stable isotope-labeled internal standard13 called C6-lyso-Gb3 (unpublished data).

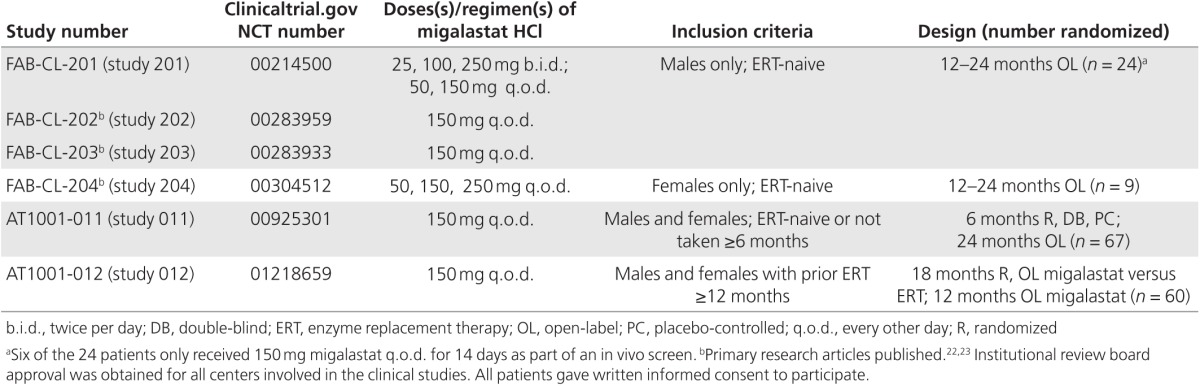

The clinical studies included in these analyses are summarized in Table 1. Supplementary Table S2 online lists the clinical studies and other sources used for comparison with each pharmacodynamic endpoint (α-Gal A, kidney GL-3 inclusions, and plasma lyso-Gb3).

Table 1. Summary of clinical studies.

Comparison of amenable mutations from migalastat phase II and phase III clinical studies and all identified Fabry disease–associated amenable mutations

The following parameters were used to compare the two groups of amenable mutations:

1. Mean absolute increase and α-Gal A activity fold over baseline in response to 10 μmol/l migalastat

2. The proportion of amenable mutations grouped by phenotype

3. Mean baseline α-Gal A activity

4. Absolute increase and α-Gal A activity fold over baseline as a function of baseline

5. The proportion of conservative and nonconservative amino acid substitutions

6. The locations of the mutations within the structure of the GLA gene

7. The locations of substituted amino acid residues within the structure of α-Gal A

Pharmacogenetic reference table

Supplementary Table S11A,B online categorizes GLA mutations tested to date as amenable or nonamenable based on the GLP HEK assay.

Results

Mutant α-Gal A responses in the GLP HEK assay

The 600 α-Gal A mutant forms that were tested spanned the length of the GLA gene and showed a wide range of enzyme activities at baseline and following incubation with 10 µmol/l migalastat (Supplementary Figure S2 online; Supplementary Table S1 online). In response to 10 μmol/l migalastat, 360 mutant forms showed a statistically significant increase in α-Gal A activity; 268 mutant forms—approximately 45%—met the amenable mutation criteria and 332 mutant forms did not.

Degree of consistency between mutant α-Gal A responses to migalastat in the GLP HEK assay and in male Fabry patient–derived lymphoblast cell lines

The α-Gal A activity in the absence and presence of a migalastat concentration-response curve (with top concentrations up to 20 mmol/l migalastat) were previously reported in 74 male Fabry disease lymphoblast cell lines.11 Baseline activity and maximum α-Gal A activity after migalastat incubation in the GLP HEK assay (i.e., after 10 µmol/l migalastat) and the male lymphoblasts (i.e., at the top of the concentration-response curve) were significantly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were 0.7375 (n = 74) and 0.7869 (n = 74), respectively, with two-tailed P values <0.0001 for each). Although the correlations indicate a high degree of consistency in α-Gal A activity between the two assays, some mutant forms with high EC50 (effective concentration 50, i.e., the concentration of migalastat yielding 50% of the maximal effect) values and/or small statistically significant responses to migalastat in lymphoblasts did not meet the threshold level of response required by the amenable mutation criteria in GLP HEK assay. Thus, further comparison was evaluated by calculating the sensitivity and specificity after the amenable mutation criteria were applied to both datasets. The sensitivity and specificity26,27 were calculated to be 0.92 and 0.89, respectively (Supplementary Material online), again indicating a high degree of consistency between the two sets of results.

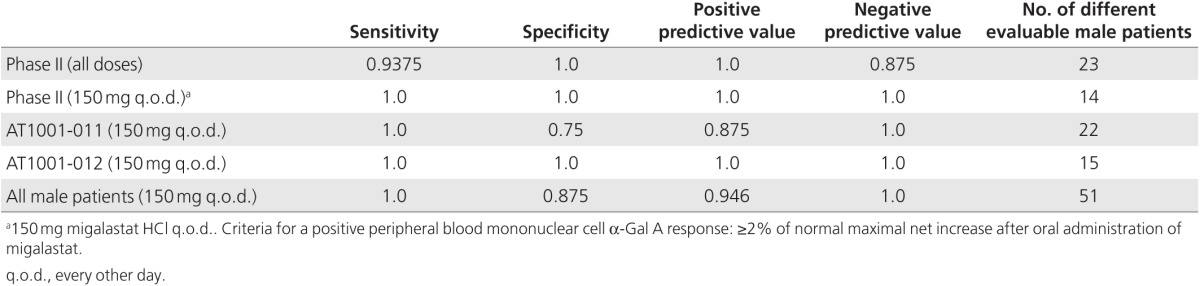

Comparison of mutant α-Gal A responses to migalastat in the GLP HEK assay and PBMCs in 51 male Fabry patients from phase II and phase III clinical studies

Supplementary Table S2 online provides the clinical study sources for these analyses. PBMCs derived from female patients were not included because the cells are a mixture that may express either wild-type or mutant α-Gal A.18 Based on sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values (≥0.875, n = 51, Table 2; Supplementary Tables S3–S6 online), there was a high degree of consistency between the GLP HEK assay and male patient PBMC results from phase II and phase III clinical studies. The predictive values based on male patients in only phase II studies (all doses and regimens or only 150 mg every other day (q.o.d.) and phase III studies AT1001-011 (study 011) or AT1001-012 (study 012) were also found to show high degrees of consistency. The ranges for all comparisons were as follows: sensitivity, 0.9375–1.0; specificity, 0.75–1.0; positive predictive value, 0.875–1.0; and negative predictive value, 0.875–1.0 (Table 2; Supplementary Tables S3–S6 online).

Table 2. Assessment of consistency between α-Gal A responses from male-derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells in phase II and III studies and GLP HEK assay.

Comparison of mutant α-Gal A responses to migalastat in the GLP HEK assay and Fabry patient substrate responses

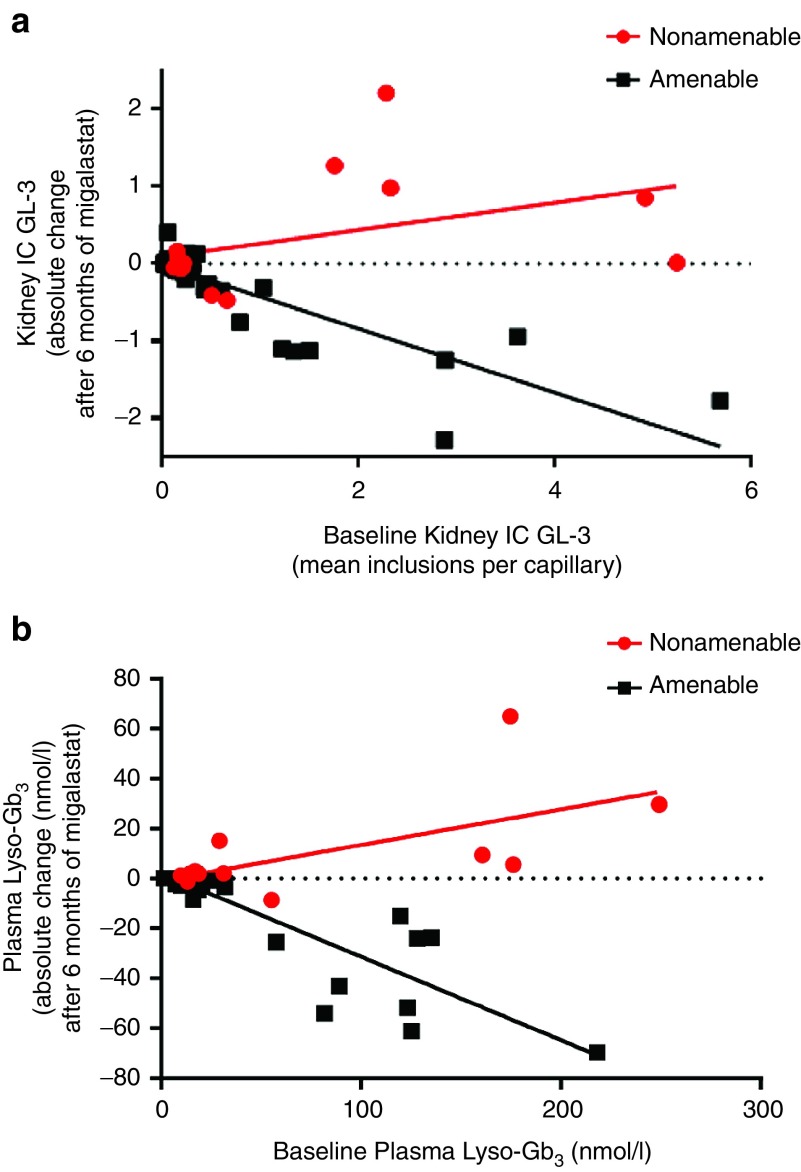

Kidney interstitial capillary GL-3. In study 011 (ERT-naive patients), the absolute change in the mean number of GL-3 inclusions per kidney interstitial capillary after 6 months of treatment with migalastat was calculated for evaluable male and female patients with amenable (n = 42) and nonamenable (n = 14) mutations and plotted as a function of the mean number of GL-3 inclusions per kidney interstitial capillary at baseline (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Substrate changes following migalastat treatment by amenability category. (a) (top): Kidney interstitial capillary GL-3 absolute change after 6 months of treatment with migalastat grouped by amenability category. Study 011 combines male and female patients receiving 6 months of migalastat (baseline to month 6 for patients randomized to migalastat at baseline, plus month 6 to month 12 for male patients receiving placebo from baseline to month 6). IC GL-3: mean number of GL-3 inclusions per interstitial capillary. Baseline refers to the kidney IC GL-3 value during the study 011 baseline visit (visit 1) for patients treated with migalastat during stages 1 and 2; it refers to the kidney IC GL-3 value at month 6 for patients treated with placebo during stage 1 and migalastat during stage 2. The mean (minimum, maximum) baseline IC GL-3 values for patients with amenable and nonamenable mutations were 0.646 (0.013, 5.692; n = 42) and 1.350 (0.117, 5.248; n = 14), respectively. After 6 months of treatment, the mean changes (95% confidence interval) from baseline for patients with amenable and nonamenable mutations were −0.282 (−0.455, −0.109; n = 42) and 0.324 (−0.105, 0.752; n = 14), respectively. The mean difference (95% confidence interval) in the change from baseline after 6 months (amenable minus nonamenable) was −0.606 (−1.059, −0.153). (b) (bottom): Plasma lyso-Gb3 absolute change after 6 months of treatment with migalastat grouped by amenability category. Study 011 combines male and female patients receiving 6 months of migalastat (baseline to month 6 for patients randomized to migalastat at baseline, plus month 6 to month 12 for patients receiving placebo from baseline to month 6). Baseline refers to the plasma lyso-Gb3 value during the study 011 baseline visit (visit 1) for patients treated with migalastat during stage 1 and stage 2; it refers to the kidney IC GL-3 value at month 6 in patients treated with placebo during stage 1 and migalastat during stage 2. The mean (minimum, maximum) baseline plasma lyso-Gb3 values for patients with amenable and nonamenable mutations were 45.236 (1.187, 218.333; n = 31) and 74.396 (9.720, 249.333; n = 13), respectively. After 6 months of treatment, the mean changes (95% confidence interval) from baseline for patients with amenable and nonamenable mutations were −13.011 (−20.642, −5.380; n = 31) and 9.801 (−1.6478, 21.2498; n = 13), respectively. The mean difference (95% confidence interval) in the change from baseline after 6 months (amenable minus nonamenable) was −22.812 (−36.100, −9.524).

The results indicate that decreases in the mean number of GL-3 inclusions per kidney interstitial capillary were observed in patients with amenable mutations. Larger decreases in the mean number of GL-3 inclusions per kidney interstitial capillary were observed with increasingly higher baseline values. In patients with nonamenable mutations, there were no consistent reductions in GL-3 substrate.

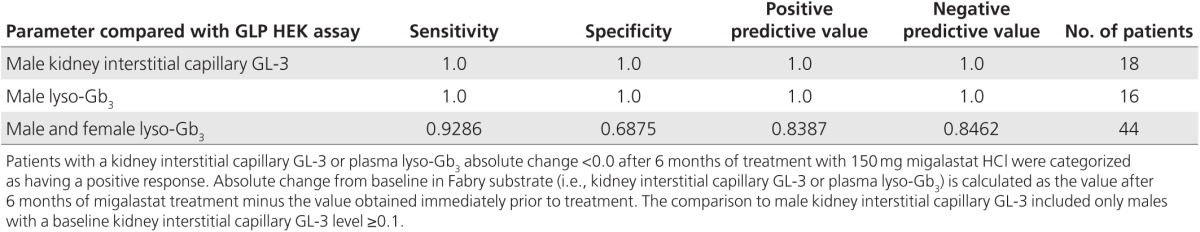

The predictive values for mutant α-Gal A responses in the GLP HEK assay with respect to changes in the mean number of GL-3 inclusions per interstitial capillary in response to migalastat were based on 18 male patients (n = 12 and n = 6 with amenable and nonamenable mutations, respectively) in study 011 with a baseline kidney interstitial capillary GL-3 level ≥0.1. A positive response was defined as a decrease in kidney interstitial capillary GL-3 after 6 months of migalastat treatment (an absolute change <0.0 from baseline). Three male patients were excluded from these analyses because their baseline interstitial capillary GL-3 was close to zero (<0.1 inclusions per capillary). All female patients were excluded because kidney interstitial capillary GL-3 levels were close to zero or more variable relative to male patients with levels ≥0.1, possibly due to the expression of a mixture of wild-type and mutant α-Gal A.18 There was a high degree of consistency between the GLP HEK assay results and kidney GL-3 findings, with all predictive values calculated to be 1.0 (Table 3; Supplementary Tables S7 and S8 online; see also Supplementary Material online).

Table 3. Assessment of consistency between mutant α-Gal A responses to migalastat in the GLP HEK assay and Fabry disease patient substrate responses in study 011.

Plasma Lyso-Gb3

In study 011 (ERT-naive patients), the absolute change in plasma lyso-Gb3 after 6 months of migalastat treatment was calculated for male and female patients with plasma lyso-Gb3 results (n = 44). The results were grouped by the GLA mutation category for patients with amenable (n = 31) and nonamenable (n = 13) mutations and plotted as a function of the baseline level (Figure 1b).

The results showed decreases within 6 months of treatment in plasma lyso-Gb3 in patients with amenable mutations, with larger decreases observed with increasingly higher baseline values. In patients with nonamenable mutations, there were no consistent reductions in lyso-Gb3.

The predictive values for mutant α-Gal A responses in the GLP HEK assay with respect to changes in plasma lyso-Gb3 were based on 16 evaluable male patients (n = 11 and n = 5 with amenable and nonamenable mutations, respectively) in study 011. A positive response was defined as a decrease in plasma lyso-Gb3 after 6 months of migalastat treatment (an absolute change <0.0 from baseline). There was a high degree of consistency between the GLP HEK assay results and plasma lyso-Gb3 findings (Table 3; Supplementary Table S8 online). All predictive values for male patients were calculated to be 1.0 (see also Supplementary Material online). The predictive values for all male and female patients (n = 44; 31 amenable and 13 nonamenable mutations) also indicated a high degree of consistency (Table 3; Supplementary Table S8 online).

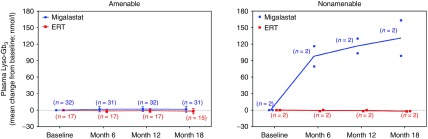

In study 012, patients using ERT (agalsidase alfa or beta) either were randomized to continue receiving ERT or were switched to migalastat (150 mg q.o.d.) for 18 months. Of the 60 patients randomized, 56 had amenable mutations and 4 had nonamenable mutations. The results (Figure 2) showed that in patients with amenable mutations, the plasma lyso-Gb3 levels remained stable for 18 months following a switch from ERT to migalastat, which is comparable to those seen in patients who continued using ERT. In patients with nonamenable mutations (two males), plasma lyso-Gb3 levels increased following the switch from ERT to migalastat, as compared to two patients (one male and one female) who continued using ERT.

Figure 2.

Plasma lyso-Gb3 absolute change from baseline after treatment with migalastat grouped by GLA mutation category. Study 012 changes from baseline in patients with amenable and nonamenable GLA mutations. Blue dotted lines represent zero change from baseline. Left: Data points represent the mean, error bars represent the standard deviation, and values in parentheses represent the number (n) of patients with amenable mutations. At month 18, in patients with amenable mutations, the mean changes (95% confidence interval) from baseline for migalastat and ERT were 1.728 (−0.301, 3.758) and −1.926 (−4.632, 0.781), respectively. Right: Data points are from individual patients with nonamenable mutations. Lines represent the mean, values in parentheses represent the number (n) of patients with nonamenable mutations. Due to small sample sizes, no statistical comparisons were made for patients with nonamenable mutations. Data are based on patients with available samples for this analysis.

Exploratory comparison of the increase in α-Gal A activity for amenable mutant forms in the GLP HEK assay and substrate reduction in patients following migalastat treatment

The relationship between the quantitative GLP HEK assay responses for amenable mutant forms and the amount of substrate reduction in patients with amenable mutations in study 011 was explored. In the subset of amenable α-Gal A mutant forms, the GLP HEK assay absolute increase and α-Gal A activity fold over baseline were each compared with the absolute change in substrate after 6 months of treatment with migalastat in patients with amenable mutations in study 011:

Absolute change in kidney GL-3 inclusions in male patients: Pearson correlation coefficients (r): 0.2172 (n = 12; P = 0.4978) and −0.0712 (n = 11; P = 0.8353), respectively (two-tailed P values) (Supplementary Figure S3 online)

Absolute change in plasma lyso-Gb3 in male patients: Pearson correlation coefficients (r): 0.1653 (n = 11; P = 0.6272) and −0.0248 (n = 10; P = 0.9458), respectively (two-tailed P values) (Supplementary Figure S4 online)

Absolute change in plasma lyso-Gb3 in male and female patients: Pearson correlation coefficients (r): 0.0328 (n = 31; P = 0.8608) and 0.2130 (n = 30; P = 0.2584), respectively (two-tailed P values) (Supplementary Figure S5 online)

Comparison of amenable mutations from migalastat phase II and phase III clinical studies and all identified Fabry disease–associated amenable mutations

Supplementary Tables S9 and S10 online list the unique amenable (total = 51) and the unique nonamenable (total = 22) mutations from 160 patients in phase II and phase III clinical studies. Fifty-one different amenable mutations were identified in 126 patients, representing 19% (51/268) of all amenable mutations categorized to date. These 51 mutant forms of α-Gal A were compared to all 268 amenable mutations.

Mean absolute and fold over baseline response to 10 μmol/l migalastat

The mean absolute increase and fold over baseline of the 51 mutant forms (24.7 ± 1.7 and 6.1 ± 0.8, respectively) were comparable to the corresponding changes for all 268 amenable mutations (23.7 ± 0.9 and 4.9 ± 0.3, respectively) (Supplementary Figure S6 online).

Proportion of amenable mutations grouped by phenotype

Clinical phenotypes based on published reports of Fabry disease–associated mutations tested in the GLP HEK assay are provided in the Supplementary Material online.

Based on published reports of clinical phenotypes associated with the amenable mutations of patients in clinical studies compared to all amenable mutations identified in the GLP HEK assay, the proportions of amenable mutations within each category were similar (Supplementary Figure S7 online). The majority were associated with the classic Fabry phenotype.

Additional comparisons

Results from additional comparisons of the two subsets of amenable mutations (Supplementary Figures S8–S12 online) indicate that the subset identified in the clinical studies is representative of all amenable mutant forms identified by the GLP HEK assay. The amenable mutant forms with higher baseline activity tended to have a greater absolute increase (Supplementary Figure S9 online), whereas the α-Gal A activity fold over baseline was greater for those mutants with lower baseline activity (Supplementary Figure S10 online).

Pharmacogenetic reference table

A pharmacogenetic reference table that categorizes GLA mutations based on the GLP HEK assay was compiled (Supplementary Table S11A,B online). Two hundred sixty-eight GLA mutations met the amenable mutation criteria (Supplementary Table S11A online) but 332 did not (Supplementary Table S11B online). The remaining 241 mutations that included large deletions, insertions, truncations, frameshift mutations, and splice-site mutations did not qualify for testing in the GLP HEK assay and were categorized as nonamenable without testing.

Discussion

The GLP-validated HEK assay (migalastat amenability assay) was developed to identify Fabry patients with amenable mutant forms of α-Gal A for treatment with migalastat. The assay does not require patient samples and is applicable to male and female patients. Approximately 800 GLA Fabry disease–causing mutations have been identified to date, with the majority being missense. Previous reports had speculated that an in vitro assay that measures the mutant α-Gal A response to migalastat may be useful in the identification of Fabry patients for treatment with a pharmacological chaperone.16,17 The results obtained with the GLP HEK assay provide clinical validation and generalizability of the assay for identification of male and female patients with Fabry disease for treatment with migalastat.

The predictive value of the GLP HEK assay and the amenability criteria were assessed based on Fabry patient pharmacodynamic responses in phase II and III clinical studies. Seventy-three unique amenable and nonamenable mutations were represented in these studies. The mutant α-Gal A responses in the GLP HEK assay were compared to α-Gal A activity and levels of disease substrate (kidney GL-3 and plasma lyso-Gb3). The accumulation of GL-3 in different kidney cell types is a known consequence of Fabry disease,1 and reduction of this substrate is a recognized beneficial treatment outcome.22,28 Plasma lyso-Gb3 also has become increasingly recognized as an important marker of disease severity.29,30

The comparisons between the GLP HEK assay amenable/nonamenable mutation results, PBMC α-Gal A activity, and disease substrate responses for Fabry patients after oral administration of migalastat revealed a high degree of consistency. High sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values strongly support the clinical validity of the GLP HEK assay for identifying Fabry disease patients amenable to treatment with migalastat. The analysis of the GLP HEK assay responses for amenable mutant forms indicated that these cell-based results did not quantitatively predict the magnitude of substrate reduction in treated patients. This is perhaps not surprising because, as with other treatments for Fabry, the magnitude of substrate reduction may be affected by many factors, including baseline disease severity, systemic risk factors, or modifier genes.31,32

The characteristics of the amenable mutant forms of α-Gal A from patients were similar to those for all amenable mutant forms categorized to date with the GLP HEK assay. Comparisons included absolute increases in α-Gal A activity, α-Gal A activity fold over baseline, the proportions associated with different Fabry phenotypes, and locations of the substituted amino acids. A majority (~70%) of amenable mutations in the clinical study subset and the larger subset were associated with classic Fabry disease based on published literature describing these mutations. The classic Fabry phenotype describes patients with early-onset, low residual α-Gal A activity (in male patients), multi-organ system disease, and elevated plasma lyso-Gb3.29,33,34 This indicates that patients amenable to treatment with migalastat commonly have classic Fabry disease.

The pharmacogenetic reference table (Supplementary Table S11A,B online) categorizes the amenability of approximately 800 Fabry disease–associated mutations. Six hundred qualified mutant forms of α-Gal A were tested with the GLP HEK assay. Two hundred sixty-eight met the amenability criteria. The majority of amenable mutations were missense, but some were small in-frame insertions or deletions. GLA mutations that did not qualify for testing with the GLP HEK assay were most commonly large deletions, insertions, truncations, frameshift mutations, and splice-site mutations, which often led to the loss of gross structural protein domains and loss of α-Gal A expression. These were considered nonamenable without testing with the GLP HEK assay. The pharmacogenetic reference table can be integrated into clinical practice to identify patients for treatment with migalastat and updated as new mutations are identified. The standard diagnostic workup for patients with Fabry disease includes genotyping to confirm the presence of a GLA mutation.

Because we primarily used Human Gene Mutation Database and literature-based sources to identify Fabry disease–associated mutations, the classifications of pathogenicity may vary or may be debatable for some. Most α-Gal A mutant forms studied with the GLP HEK assay have little to no baseline activity, suggesting pathogenicity. However, some mutant forms have been identified with normal or near-normal baseline activity in the GLP HEK assay. The GLP HEK assay and the pharmacogenetic reference table are not intended to be used to define mutations as pathogenic or to aid in the diagnosis of Fabry disease. The intended use is to identify Fabry patients with amenable mutant forms of α-Gal A for treatment with migalastat.

Orally administered migalastat is being developed as an alternative to ERT for the treatment of Fabry disease in patients with amenable mutations. Migalastat acts as a pharmacologic chaperone by selectively and reversibly binding to the active site of amenable mutant forms of α-Gal A. Migalastat binding to and stabilizing amenable mutant forms of α-Gal A may increase α-Gal A enzyme levels in a more consistent fashion than ERT infusions every other week. The higher volume of distribution of migalastat relative to ERT19 suggests that the pharmacological chaperone is distributed to many different cells and tissues, which may enhance α-Gal A levels in multiple organs, including the brain.8 As an orally administered small molecule, ERT-associated immunogenicity and infusion-associated reactions would be avoided with migalastat.

In recently completed phase III studies (unpublished data; ref. 24), migalastat treatment resulted in significant reductions in disease substrate in patients with amenable mutations, with efficacy in organ systems affected by the disease. The development and clinical validation of the GLP-validated HEK assay were critical for identifying Fabry patients with mutant forms of α-Gal A that are amenable to treatment with migalastat. Based on the current study, the GLP HEK assay is now a clinically validated pharmacogenetic method of identifying male and female Fabry patients for treatment with migalastat. The associated pharmacogenetic reference table could be integrated into clinical practice.

Disclosure

E.R.B., C.D.V., X.W., E.K., F.P., H.W., J.Y., J.K., J.B., K.J.V., and J.C. are employed by Amicus Therapeutics, Inc., and own shares in the company. S.B. and B.B. are employed by Cambridge Biomedical Inc. (Boston, MA), which received payment for the GLP validation of the HEK assay. D.J.L. is a former employee of Amicus Therapeutics, Inc. C.B. is a former contractor of Amicus Therapeutics, Inc. D.G.B. received grants from Amicus Pharmaceuticals and nonfinancial support from Amicus Pharmaceuticals outside of the submitted work. D.P.G., D.H., R.S., W.R.W., and R.G. received personal fees from Amicus Therapeutics outside of the submitted work. R.J.D. received grants from Alexion, Alnylam, and Amicus, owns shares in Alexion and Amicus, and receives royalties from Genzyme/Sanofi and Shire HGT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and clinical investigators who participated in the migalastat clinical program. Cambridge Biomedical Inc. (Boston, MA) performed GLP validation of the HEK assay and mutation testing. The study and its publication were funded by Amicus Therapeutics, Inc., Cranbury, NJ. The ClinicalTrials.gov registration IDs are NCT00214500 (FAB-CL-201), NCT00283959 (FAB-CL-202), NCT00283933 (FAB-CL-203), NCT00304512 (FAB-CL-204), NCT00925301 (AT1001-011), and NCT01218659 (AT1001-012).

Supplementary Material

References

- Brady RO, Gal AE, Bradley RM, Martensson E, Warshaw AL, Laster L. Enzymatic defect in Fabry's disease. Ceramidetrihexosidase deficiency. N Engl J Med 1967;276:1163–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP. Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010;5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal A, Schäfer E, Rohard I. The genetic basis of Fabry disease. In: Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G (eds). Fabry Disease: Perspectives From 5 Years of FOS. Oxford PharmaGenesis: Oxford, UK, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP, Shabbeer J, Cotigny S, Desnick RJ. Fabry disease: twenty novel alpha-galactosidase A mutations and genotype-phenotype correlations in classical and variant phenotypes. Mol Med 2002;8:306–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filoni C, Caciotti A, Carraresi L, et al. Functional studies of new GLA gene mutations leading to conformational Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1802:247–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topaloglu AK, Ashley GA, Tong B, et al. Twenty novel mutations in the alpha-galactosidase A gene causing Fabry disease. Mol Med 1999;5:806–811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabbeer J, Yasuda M, Benson SD, Desnick RJ. Fabry disease: identification of 50 novel alpha-galactosidase A mutations causing the classic phenotype and three-dimensional structural analysis of 29 missense mutations. Hum Genomics 2006;2:297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Soska R, Lun Y, et al. The pharmacological chaperone 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin reduces tissue globotriaosylceramide levels in a mouse model of Fabry disease. Mol Ther 2010;18:23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam GH, Zuber C, Roth J. A synthetic chaperone corrects the trafficking defect and disease phenotype in a protein misfolding disorder. FASEB J 2005;19:12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan JQ, Ishii S, Asano N, Suzuki Y. Accelerated transport and maturation of lysosomal alpha-galactosidase A in Fabry lymphoblasts by an enzyme inhibitor. Nat Med 1999;5:112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin ER, Flanagan JJ, Schilling A, et al. The pharmacological chaperone 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin increases alpha-galactosidase A levels in Fabry patient cell lines. J Inherit Metab Dis 2009;32:424–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam GH, Bosshard N, Zuber C, Steinmann B, Roth J. Pharmacological chaperone corrects lysosomal storage in Fabry disease caused by trafficking-incompetent variants. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006;290:C1076–C1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemansky P, Bishop DF, Desnick RJ, Hasilik A, von Figura K. Synthesis and processing of alpha-galactosidase A in human fibroblasts. Evidence for different mutations in Fabry disease. J Biol Chem 1987;262:2062–2065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Murray GJ, Kluepfel-Stahl S, et al. Screening for pharmacological chaperones in Fabry disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;359:168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S, Kase R, Okumiya T, Sakuraba H, Suzuki Y. Aggregation of the inactive form of human alpha-galactosidase in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;220:812–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Katz E, Della Valle MC, et al. A pharmacogenetic approach to identify mutant forms of α-galactosidase A that respond to a pharmacological chaperone for Fabry disease. Hum Mutat 2011;32:965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas J, Giese AK, Markoff A, et al. Functional characterisation of alpha-galactosidase a mutations as a basis for a new classification system in fabry disease. PLoS Genet 2013;9:e1003632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria L, Benistan K, Toussaint A, et al. X-chromosome inactivation in female patients with Fabry disease. Clin Genet 2016;89:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson FK, Mudd PN Jr, Bragat A, Adera M, Boudes P. Pharmacokinetics and safety of migalastat HCl and effects on agalsidase activity in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2013;2:120–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conzelmann E, Sandhoff K. Partial enzyme deficiencies: residual activities and the development of neurological disorders. Dev Neurosci 1983;6:58–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnick RJ. Enzyme replacement and enhancement therapies for lysosomal diseases. J Inherit Metab Dis 2004;27:385–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP, Giugliani R, Hughes DA, et al. Safety and pharmacodynamic effects of a pharmacological chaperone on α-galactosidase A activity and globotriaosylceramide clearance in Fabry disease: report from two phase 2 clinical studies. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giugliani R, Waldek S, Germain DP, et al. A Phase 2 study of migalastat hydrochloride in females with Fabry disease: selection of population, safety and pharmacodynamic effects. Mol Genet Metab 2013;109:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP, Hughes DA, Nicholls K, et al. Treatment of Fabry's disease with the pharmacologic chaperone Migalastat. N Engl J Med 2016;375:545–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisoni L, Jennette JC, Colvin R, et al. Novel quantitative method to evaluate globotriaosylceramide inclusions in renal peritubular capillaries by virtual microscopy in patients with fabry disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;136:816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics Notes: diagnostic tests 1: sensitivity and specificity. BMJ 1994;308:1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics Notes: diagnostic tests 2: predictive values. BMJ 1994;309:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng CM, Banikazemi M, Gordon RE, et al. A phase ½ clinical trial of enzyme replacement in fabry disease: pharmacokinetic, substrate clearance, and safety studies. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:711–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombach SM, Dekker N, Bouwman MG, et al. Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine: diagnostic value and relation to clinical manifestations of Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1802:741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Breemen MJ, Rombach SM, Dekker N, et al. Reduction of elevated plasma globotriaosylsphingosine in patients with classic Fabry disease following enzyme replacement therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1812:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries M, Gal A. Genotype-phenotype correlation in Fabry disease. In: Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G (eds). Fabry Disease: Perspectives From 5 Years of FOS. Oxford PharmaGenesis: Oxford, UK, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altarescu G, Moore DF, Schiffmann R. Effect of genetic modifiers on cerebral lesions in Fabry disease. Neurology 2005;64:2148–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnick RJ, Brady R, Barranger J, et al. Fabry disease, an under-recognized multisystemic disorder: expert recommendations for diagnosis, management, and enzyme replacement therapy. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ, et al.; Fabry Registry. Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol Genet Metab 2008;93:112–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.