Abstract

The Mga2 and Sre1 transcription factors regulate oxygen-responsive lipid homeostasis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe in a manner analogous to the mammalian sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1 and SREBP-2 transcription factors. Mga2 and SREBP-1 regulate triacylglycerol and glycerophospholipid synthesis, whereas Sre1 and SREBP-2 regulate sterol synthesis. In mammals, a shared activation mechanism allows for coordinate regulation of SREBP-1 and SREBP-2. In contrast, distinct pathways activate fission yeast Mga2 and Sre1. Therefore, it is unclear whether and how these two related pathways are coordinated to maintain lipid balance in fission yeast. Previously, we showed that Sre1 cleavage is defective in the absence of mga2. Here, we report that this defect is due to deficient unsaturated fatty acid synthesis, resulting in aberrant membrane transport. This defect is recapitulated by treatment with the fatty acid synthase inhibitor cerulenin and is rescued by addition of exogenous unsaturated fatty acids. Furthermore, sterol synthesis inhibition blocks Mga2 pathway activation. Together, these data demonstrate that Sre1 and Mga2 are each regulated by the lipid product of the other transcription factor pathway, providing a source of coordination for these two branches of lipid synthesis.

Keywords: fatty acid metabolism, hypoxia, lipid metabolism, membrane transport, transcription regulation, yeast, SREBP, mga2, sre1

Introduction

The fission yeast sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)2 transcription factor Sre1 maintains sterol homeostasis and regulates a low oxygen-responsive transcriptional program (1, 2). Sre1 is synthesized as an integral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane protein where it is sequestered under normoxic conditions. Sre1 is bound and regulated in the membrane by Scp1, a multipass transmembrane protein that senses sterols through eight transmembrane domains (1). Because synthesis of one ergosterol molecule requires 12 molecules of oxygen, the Sre1 pathway responds to oxygen availability (1, 3). Upon conditions of low oxygen, ergosterol synthesis decreases, and Scp1 transports Sre1 from the ER to the Golgi where Sre1 is proteolytically cleaved, releasing the active Sre1 N-terminal transcription factor fragment (Sre1N). A low level of Sre1-Scp1 transport and cleavage at the Golgi occurs even in the presence of oxygen, but under low oxygen or low sterols this transport is up-regulated dramatically (4). After release, Sre1N enters the nucleus and promotes transcription of sterol synthesis and oxygen-responsive genes. Sre1N also binds regulatory elements in its promoter and up-regulates its own expression in a positive feedback loop (1). In addition to Sre1, fission yeast has a second SREBP, Sre2, which is cleaved through the same mechanism as Sre1 but does not bind Scp1 and therefore is not regulated by ergosterol or oxygen levels (1). The constitutive activity of this homolog is useful for studying SREBP processing independently of Scp1 and the oxygen environment.

Fission yeast activate SREBPs in the Golgi through a unique mechanism that requires the five subunits of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase complex, dsc1-dsc5; the AAA ATPase cdc48; and the rhomboid protease rbd2 (5–7). The current model is that after transport of Sre1-Scp1 to the Golgi Sre1 is ubiquitinylated by the Dsc E3 ligase and then passed off to Rbd2 and Cdc48 for proteolytic cleavage and release of Sre1N. Proper localization of the Dsc E3 ligase in the Golgi requires that it is a functional ligase because Dsc E3 ligase subunits are retained in the ER when Dsc1 is catalytically dead or when complex members are missing (8). Therefore, ER-to-Golgi transport of multiple Sre1 pathway components, including Sre1-Scp1 and the Dsc E3 ligase, is required for Sre1 activation.

Recently, we found that the transcription factor Mga2 regulates triacylglycerol (TAG) and glycerophospholipid (GPL) homeostasis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (9). Deletion of mga2 resulted in broad lipidome disruption, a decrease in fatty acid desaturation, and an Sre1 cleavage defect. Similarly, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mga2 regulates a transcriptional program controlling fatty acid homeostasis. In S. cerevisiae, Mga2 and its homolog Spt23 are ER membrane-bound transcription factors until activated through partial proteolysis by the proteasome in response to low oxygen or increased fatty acid saturation. This cleavage releases the Mga2 transcription factor domain to up-regulate target genes, most notably the fatty acid desaturase OLE1 (10–12). Deletion of both MGA2 and SPT23 results in disrupted nuclear membrane morphology and is ultimately lethal. Addition of exogenous unsaturated fatty acid rescues these defects (13). A recent report by Covino et al. (14) described a mechanism for how S. cerevisiae Mga2 senses changes in membrane saturation. Using in silico and in vitro studies, they showed that different degrees of ER membrane lipid order stabilize distinct rotational conformations of Mga2 transmembrane helices. They proposed that highly saturated membrane conditions stabilize the transmembrane helix conformations necessary for Mga2 cleavage and activation. Interestingly, the authors conclude that Mga2 senses lipid packing and membrane fluidity rather than phospholipid saturation and suggest that Mga2 may therefore respond to changes in both fatty acid saturation and sterol levels (14). These results confirm that the S. cerevisiae Mga2 transcription factor is product-inhibited in a very similar manner to the S. pombe transcription factor Sre1. Both systems detect the presence of product in the ER membrane and are only activated for cleavage when product is decreased.

In this study, we demonstrate that the observed Sre1 cleavage defect in the absence of S. pombe mga2 correlates with a general membrane transport defect of multiple Golgi proteins. This cleavage and membrane transport defect is recapitulated by treatment with cerulenin, a fatty acid synthase inhibitor. Both Sre1 and membrane transport defects are rescued by addition of exogenous unsaturated fatty acid. We conclude that the Sre1 cleavage defect is due to mislocalization of Sre1 pathway components when fatty acid homeostasis is disrupted. Thus, Sre1 is uniquely positioned to detect changes in membrane fatty acid homeostasis due to the requirement for ER-to-Golgi transport of multiple Sre1 pathway components as well as positive feedback in the system, which magnifies small changes in Sre1 cleavage. Furthermore, we demonstrate that Mga2 cleavage in S. pombe is induced by treatment with cerulenin and inhibited by treatment with proteasome inhibitor. Chemical inhibition of sterol synthesis blocked Mga2-dependent target gene expression. Therefore, we propose that the products of both Sre1 and Mga2 transcription factor activity control the activity of the other pathway, resulting in coordination of these two branches of lipid homeostasis.

Results

mga2Δ Cells Have Reduced Sre1N Accumulation in the Presence and Absence of Oxygen

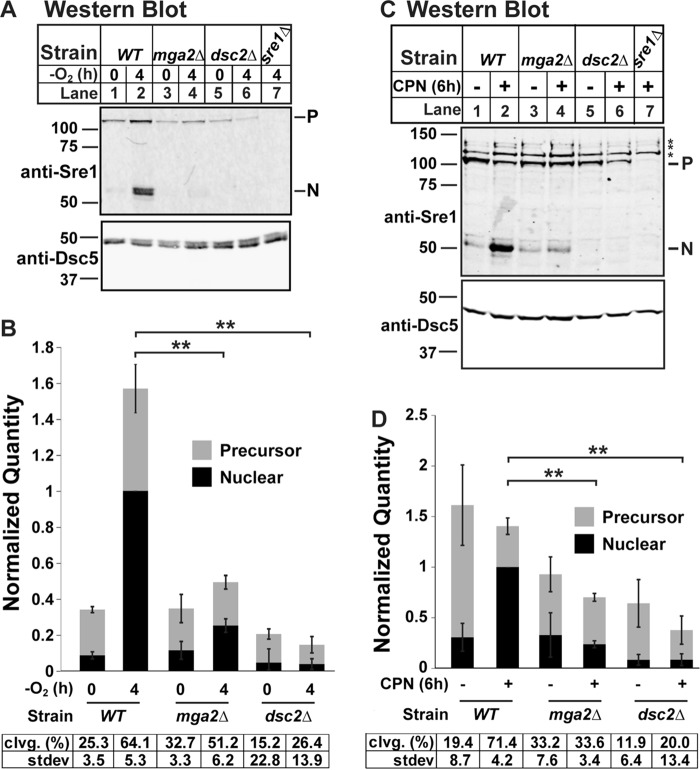

We previously screened the fission yeast deletion collection to identify regulators of Sre1 and found that mga2 deletion blocked Sre1 cleavage induction by low oxygen (9). Here, we confirmed this requirement by creating our own mga2 deletion strain (9). We cultured wild-type (WT), mga2Δ, dsc2Δ, and sre1Δ cells for 0 or 4 h minus oxygen. We then probed a Western blot of whole cell lysates with antibody against Sre1N, which detects both the Sre1 inactive membrane-bound precursor form and the cleaved N-terminal transcription factor form. As expected, WT cells accumulated cleaved Sre1N after 4 h minus oxygen, and the precursor increased due to Sre1N activation of sre1 transcription through positive feedback regulation (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 2) (1). In contrast, deletion of the Dsc E3 ligase subunit dsc2 resulted in a failure to cleave Sre1 (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 and 6). As reported, deletion of mga2 also resulted in a failure to accumulate Sre1N (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 4), leading to a 4-fold decrease in Sre1N accumulation compared with WT (Fig. 1B, lane 2 versus 4). To test whether Sre1 activation requires mga2 only under low oxygen, we assayed Sre1 cleavage in the presence of oxygen with addition of the statin drug compactin (CPN), which inhibits HMG-CoA reductase and blocks ergosterol synthesis (15). CPN induces Sre1 cleavage regardless of oxygen availability (1). CPN treatment induced Sre1 cleavage in WT cells but not mga2Δ cells (Fig. 1, C and D). Therefore, we conclude that the Sre1N accumulation defect in the absence of mga2 is independent of oxygen supply. This is consistent with results from our previous study showing that loss of mga2 disrupts TAG and GPL homeostasis under normoxic conditions (9).

FIGURE 1.

mga2Δ cells have reduced Sre1N accumulation in the presence and absence of oxygen. A and C, Western blots, probed with monoclonal anti-Sre1 IgG (5B4) and polyclonal anti-Dsc5 IgG (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h from WT, mga2Δ, dsc2Δ, or sre1Δ cells grown for 0 or 4 h in the absence of oxygen (A) or 6 h in the statin CPN (200 μm) or vehicle (0.12% EtOH, 400 μm NaCl) (C). P and N denote precursor and cleaved N-terminal transcription factor forms, respectively. Asterisks denote nonspecific bands. B and D, quantification from A and C of three (A and B) or four (C and D) biological replicates normalized for loading to Dsc5 and then normalized to maximum signal (WT N terminus band after treatment; lane 2) for comparison between blots. Error bars are 1 S.D. (**, p < 0.01 for N terminus by two-tailed Student's t test). Quantities of the precursor and nuclear form are stacked to give an approximation of total signal per treatment. Average percent cleavage (clvg.) is calculated by dividing the quantity of N terminus by the sum of both N terminus and precursor.

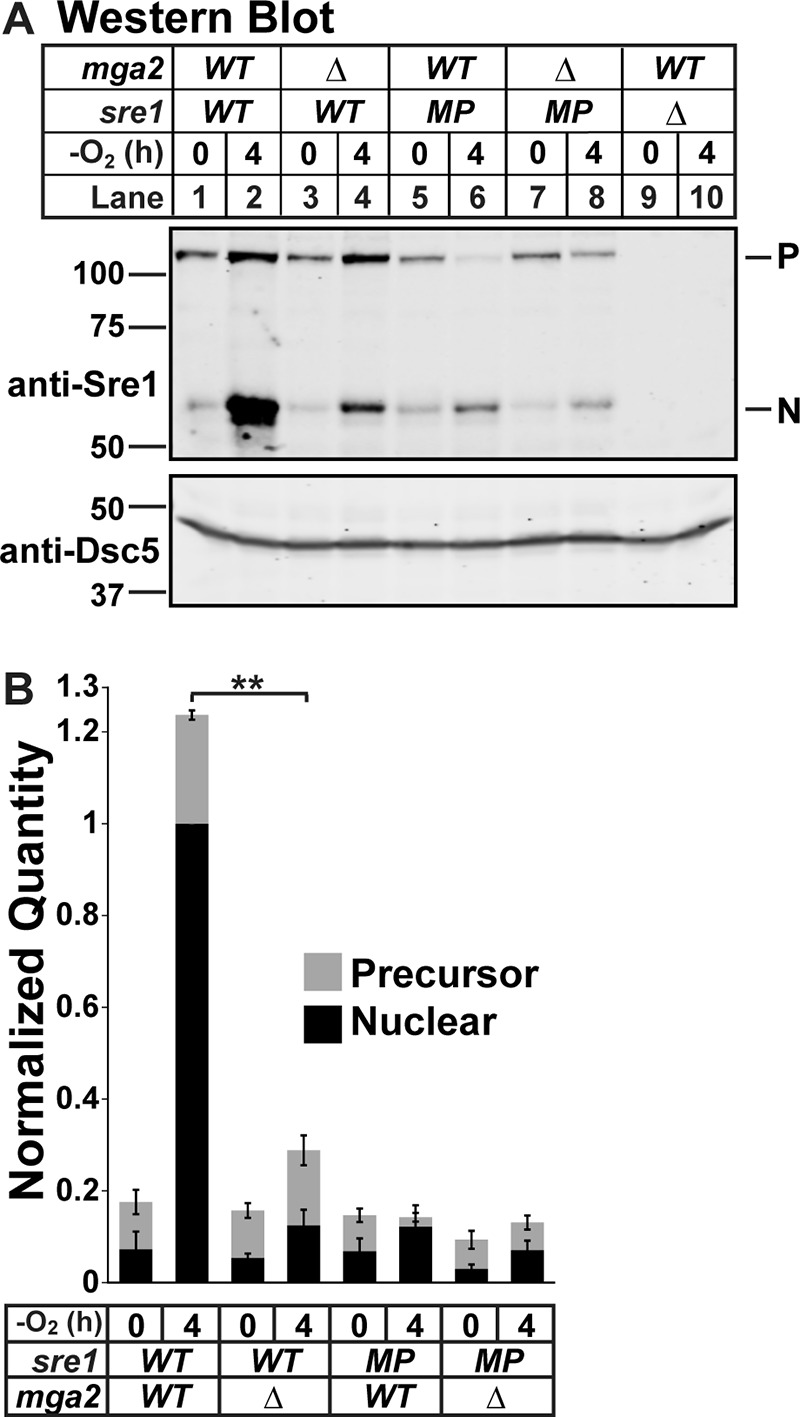

Defect in Sre1 Cleavage in the Absence of mga2 Is Amplified by Positive Feedback

Interestingly, the Sre1N accumulation defect in mga2Δ cells was not as strong as in the control dsc2Δ cells (Fig. 1, B and D, lane 4 versus 6). Although low oxygen or CPN could not induce Sre1N accumulation in the absence of mga2, basal levels of Sre1N in mga2Δ cells were close to WT in the presence of oxygen (Fig. 1, A–D, compare lanes 1 and 3). This indicated that in the absence of mga2 there was a failure to fully induce Sre1N accumulation rather than a strict block. To further dissect this, we examined Sre1N accumulation in a strain expressing sre1 from a mutant promoter (sre1-MP) in which Sre1 is not able to activate its own transcription via positive feedback (16). Thus, accumulation of Sre1N in this strain reflects only the rate of Sre1 cleavage and Sre1N degradation. Although mga2Δ cells showed a 4–8-fold decrease in Sre1N accumulation compared with WT cells (Figs. 1A, lane 2 versus 4, and 2, A and B, lane 2 versus 4), mga2Δ sre1-MP cells exhibited only a 1.5-fold decrease in accumulation compared with sre1-MP cells (Fig. 2, A and B, lane 6 versus 8). These data indicate that positive feedback to the sre1 promoter accounts for the majority of the observed difference in Sre1N accumulation and that mga2Δ cells likely fail to accumulate Sre1N to a threshold level that induces maximal sre1 transcription and positive feedback. Our previous work established that in the absence of mga2 Sre1 is successfully transcribed and translated and induces its own transcription when expressed without the membrane-anchoring domain (9). Together, these data show that the defect occurs in a step after Sre1 translation and prior to membrane release of the Sre1N transcription factor, referred to hereafter as the cleavage step.

FIGURE 2.

Defect in Sre1 cleavage in the absence of mga2 is amplified by positive feedback. A, Western blot, probed with monoclonal anti-Sre1 IgG (5B4) and polyclonal anti-Dsc5 IgG (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h from WT, mga2Δ, or sre1Δ cells with WT or sre1-MP as indicated. Cells were grown for 0 or 4 h in the absence of oxygen. P and N denote precursor and cleaved N-terminal transcription factor forms, respectively. B, quantification from A of four biological replicates normalized for loading to Dsc5 and then normalized to maximum signal (WT N terminus band after treatment; lane 2) for comparison between blots. Error bars are 1 S.D. (**, p < 0.01 for N terminus by two-tailed Student's t test). Quantities of the precursor and nuclear form are stacked to give an approximation of total Sre1 signal per treatment.

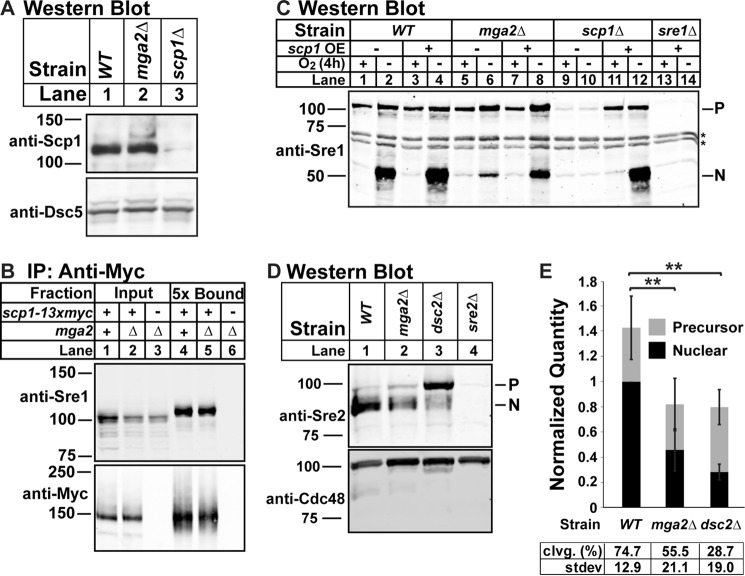

Cleavage Defect in mga2Δ Cells Occurs at a Step Downstream of Sre1-Scp1 Complex Formation and Is Not Specific to Sre1

We next wanted to further narrow down which step of Sre1 cleavage was defective in mga2Δ cells. A major point of regulation for the Sre1 pathway is the formation and ER-to-Golgi transport of the Sre1-Scp1 complex (4). Scp1 senses and responds to changes in sterol synthesis, transporting Sre1 to the Golgi for activation when sterols decrease (5). We showed previously that loss of Scp1 results in degradation of the Sre1 precursor via the Hrd1 E3 ligase (16). In mga2Δ cells, we observed wild-type levels of Sre1 precursor (Figs. 1 and 2) and Scp1 (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Therefore, low scp1 expression does not account for the observed Sre1 cleavage defect in mga2Δ cells. To test whether complex formation between Scp1 and Sre1 was disrupted in mga2Δ cells, we assayed Sre1-Scp1 binding. Immunopurification of Scp1-13xMyc recovered Sre1 precursor from scp1-13xmyc cells in both the presence and absence of mga2 (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 and 5). Together, these data indicate that the Sre1-Scp1 complex forms normally in mga2Δ cells.

FIGURE 3.

Cleavage defect in mga2Δ cells occurs at a step downstream of Sre1-Scp1 complex formation and is not specific to Sre1. A, Western blot of cell lysates from the indicated strains grown in the presence of oxygen probed with a mixture of anti-Scp1 IgG monoclonal antibodies 8G4C11, 1G1D6, and 7B4A3 (imaged by film) or anti-Dsc5 IgG (imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx). The blot is representative of four biological replicates. B, WT or mga2Δ cells expressing scp1-13xmyc and mga2Δ cells expressing untagged scp1 were grown in the presence of oxygen, and Scp1-13xMyc was immunoprecipitated (IP) from Nonidet P-40-solubilized membranes using monoclonal anti-Myc 9E10 IgG as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Input and 5-fold enriched bound fractions were analyzed by Western blotting and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx using polyclonal anti-Sre1 IgG and polyclonal anti-Myc IgG. The blot is representative of three biological replicates. C, indicated strains expressing vector (−) or scp1 (+) from a cauliflower mosaic virus promoter (17) were precultured in minimal medium lacking leucine, transferred to YES complete medium, and grown for 4 h in the presence or absence of oxygen. The Western blot was probed with anti-Sre1 IgG polyclonal antibody and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx and is representative of five biological replicates. P and N denote Sre1 precursor and N-terminal forms. Asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. D, Western blot, probed by polyclonal anti-Sre2 and polyclonal anti-Cdc48 (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h from WT, mga2Δ, dsc2Δ, or sre2Δ cells grown in the presence of oxygen. E, quantification from D of six biological replicates normalized for loading to Cdc48 and then normalized to WT N terminus band for comparison between blots. Error bars are 1 S.D. (**, p < 0.01 for N terminus by two-tailed Student's t test). Quantities of the precursor and nuclear form are stacked to give an approximation of total signal per treatment. Average percent cleavage (clvg.) is calculated by dividing the quantity of N terminus by the sum of both N terminus and precursor.

Previous work in our laboratory established that Sre1-Scp1 transport to the Golgi for cleavage is regulated both by the rate of ER-to-Golgi transport and by the amount of Sre1-Scp1 complex available in the ER (4). That model predicts that increasing Sre1-Scp1 complex concentration will increase Sre1 cleavage as long as no step of the pathway is completely blocked. Consistent with this, overexpressing scp1 in WT cells increased Sre1 cleavage under low oxygen (Fig. 3C, lanes 1–4) (17). Overexpression of scp1 in mga2Δ cells increased Sre1N to a similar proportion, although overall Sre1N accumulation was not rescued to WT levels (Fig. 3C, lanes 5–8). As expected, expression of scp1 in scp1Δ cells supported wild-type levels of Sre1 cleavage (Fig. 3C, lanes 9–12). Thus, overexpression of scp1 partially rescues the Sre1 cleavage defect in the absence of mga2, further demonstrating that there is not a complete block in Sre1 cleavage in mga2Δ cells and that Sre1-Scp1 complex formation is normal. However, overexpression of scp1 in mga2Δ cells does not rescue cleavage as well as overexpression of scp1 in scp1Δ cells, suggesting that the overexpressed Scp1 is affected by the same inhibition that blocks endogenous Sre1 cleavage in mga2Δ cells. This suggests that the defect in Sre1 activation in mga2Δ cells occurs at a step after Sre1-Scp1 complex formation.

Given our observed block in Sre1N accumulation under normoxic conditions and the normal expression and function of Scp1 in the absence of mga2, we tested cleavage of the Sre1 homolog Sre2 under normoxic conditions where Sre2 is constitutively activated independently of Scp1 or sterol levels (1). We cultured WT, mga2Δ, dsc2Δ, and sre2Δ cells under normoxia and probed a Western blot with antibody against the Sre2 N terminus (Sre2N). As observed for Sre1, deletion of the Dsc E3 ligase subunit dsc2 resulted in a failure to cleave Sre2 and accumulation of Sre2 precursor (Fig. 3D, lane 3). Deletion of mga2 resulted in an intermediate Sre2 cleavage defect (Fig. 3D, lane 2), resulting in a 2-fold decrease in Sre2N (Fig. 3E, lane 1 versus 2). Therefore, we conclude that Sre2 cleavage is also defective in the absence of mga2 and that the defect in these cells is not specific to the Sre1-Scp1 complex activity.

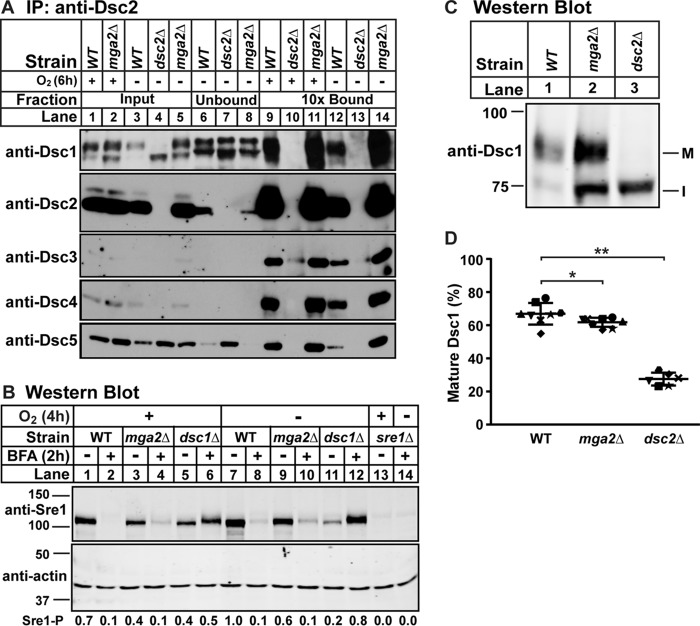

Dsc E3 Ligase Is Functional in mga2Δ Cells

In addition to Sre1-Scp1 complex formation, Sre1 cleavage and Sre2 cleavage both require Dsc E3 ligase activity (5, 6). To examine Dsc E3 ligase function in the absence of mga2, we first assayed Dsc E3 ligase complex assembly by immunopurifying Dsc2 in WT, dsc2Δ, or mga2Δ cells in the presence and absence of oxygen (Fig. 4A). We efficiently purified the Dsc E3 ligase complex from WT but not dsc2Δ cells and found no difference in complex formation between WT and mga2Δ cells in both oxygen conditions (Fig. 4A, lanes 9–14). This result indicates that Dsc E3 ligase complex assembly is not disrupted in mga2Δ cells.

FIGURE 4.

Dsc E3 ligase is functional in mga2Δ cells. A, digitonin-solubilized membrane protein was prepared from WT, mga2Δ, or dsc2Δ cells grown in the presence or absence of oxygen for 6 h, and the Dsc E3 ligase complex was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Dsc2 polyclonal IgG as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Equal quantities of input, unbound, and 10-fold bound fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using HRP-conjugated antibodies against Dsc1, Dsc2, Dsc3, Dsc4, and Dsc5 (imaged by film). The blot is representative of three biological replicates. B, Western blot, probed with polyclonal anti-Sre1 IgG and monoclonal anti-actin (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates from WT, mga2Δ, dsc1Δ, or sre1Δ yeast grown for 2 h in the presence or absence of oxygen and then treated with BFA (100 μg/ml) or EtOH vehicle for another 2 h in the presence or absence of oxygen. Quantification of Sre1 precursor (Sre1-P) normalized to WT vehicle in the absence of oxygen (lane 7) is shown below. The blot is representative of two biological replicates. C, Western blot, probed with polyclonal anti-Dsc1 IgG and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of Nonidet P-40-solubilized membrane protein from WT, mga2Δ, or dsc2Δ cells grown in the presence of oxygen. M and I indicate mature and intermediate glycosylated forms, respectively. D, quantification of Dsc1 from C of seven replicates. The quantity of the mature form was divided by total Dsc1 signal for percent mature, allowing comparison between lanes and blots. Error bars are 1 S.D. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by two-tailed Student's t test).

To confirm that the Dsc E3 ligase is not only assembled but also functional, we forced co-localization of the Dsc E3 ligase and Sre1 in the presence and absence of oxygen using brefeldin A (BFA). In BFA-treated cells, the ER and Golgi compartments mix, the Dsc E3 ligase and Sre1 co-localize, and the Sre1 precursor is degraded in a Dsc-dependent manner (5). To assess function of the Dsc E3 ligase, we assayed Sre1 precursor degradation in mga2Δ cells after BFA treatment. As expected, Sre1 precursor decreased upon BFA treatment in WT cells in both the presence and absence of oxygen (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2 and lanes 7 and 8). Degradation of Sre1 precursor upon BFA treatment was blocked in dsc1Δ cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 11 and 12), indicating that this Sre1 precursor degradation requires Dsc E3 ligase activity (5). Interestingly, the Sre1 precursor level increased upon addition of BFA in dsc1Δ cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 11 and 12), suggesting that BFA treatment prevented degradation of Sre1 by multiple mechanisms in dsc1Δ cells. Notably, Sre1 precursor was degraded normally in mga2Δ cells, demonstrating that the Dsc E3 ligase is functional in mga2Δ cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4 and lanes 9 and 10). Therefore, the Sre1 cleavage defect in the absence of mga2 is not due to a defect in Dsc E3 ligase activity, suggesting that the defect occurs before Sre1 cleavage at the Golgi, such as during ER-to-Golgi transport of pathway components.

We next tested whether the Dsc E3 ligase complex localizes properly to the Golgi (5). We can monitor Dsc E3 ligase localization by assaying maturation of Dsc1 N-linked glycosylation, which requires transport to the Golgi (8). As described previously, in WT cells transport of the Dsc E3 ligase to the Golgi led to the accumulation of Dsc1 primarily as a slower migrating, mature glycosylated form by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4, C and D, lane 1). In contrast, failure to properly assemble the Dsc E3 ligase complex in dsc2Δ cells resulted in detection of only the faster migrating, incompletely glycosylated form due to ER retention of Dsc1 (Fig. 4, C and D, lane 3) (8). In mga2Δ cells, Dsc1 existed in both forms, representing accumulation of some incompletely glycosylated protein (Fig. 4, C and D, lane 2). This suggested that the majority of Dsc1 was appropriately glycosylated. However, there was a small decrease in the percentage of Dsc1 that was fully glycosylated compared with WT, suggesting a defect in Dsc E3 ligase transport to the Golgi. These results demonstrate that the Dsc E3 ligase is assembled and functional in the absence of mga2 but that there may be a membrane trafficking defect in mga2Δ cells.

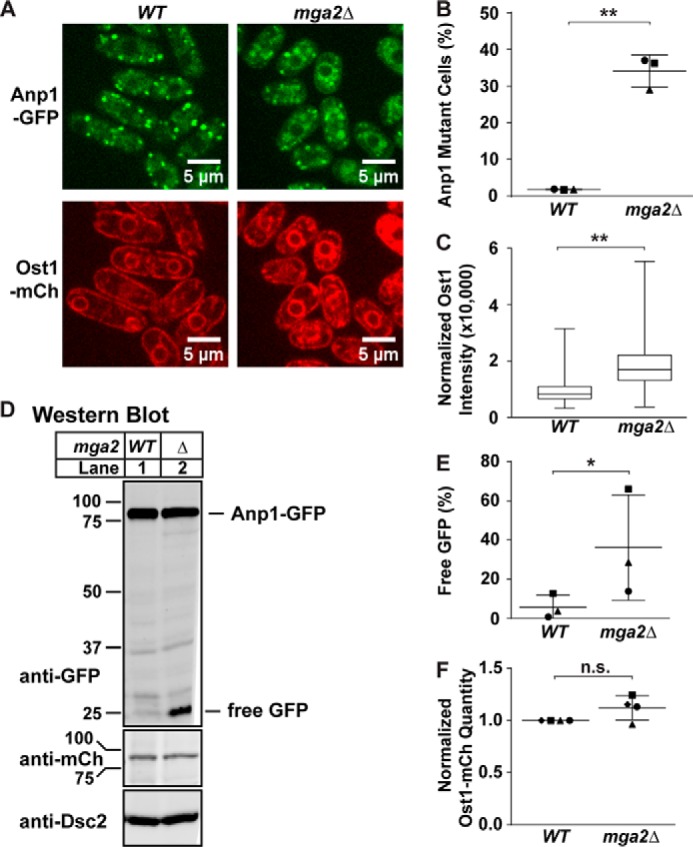

Membrane Transport Is Disrupted in the Absence of mga2

We wondered whether the small change in Golgi localization of the Dsc E3 ligase was due to a general defect in membrane transport caused by the altered lipid composition in mga2Δ cells. Lipid homeostasis, especially proper fatty acid saturation, is essential for proper membrane structure and fluidity (18). Defects in lipid homeostasis have wide ranging effects, including altering membrane-bound enzyme function and activating signal transduction pathways (9, 19, 20). To determine whether general membrane transport is deficient in the absence of mga2, we visualized localization of the Golgi marker Anp1-GFP and the ER marker Ost1-mCherry. Previous work in our laboratory showed that Anp1 localized to the ER when ER exit is blocked using a sar1ts mutant that is defective in coat protein complex II (COPII) vesicle formation (5, 24). Anp1-GFP localized to punctate Golgi structures in 98% of WT cells (Fig. 5, A and B). However, 34% of mga2Δ cells exhibited altered Anp1-GFP localization phenotypes, defined as no discernable GFP signal or complete or partial co-localization with Ost1-mCherry in the ER (perinuclear and around the cell periphery) (Fig. 5, A and B). Anp1-GFP also localized to the vacuole in mga2Δ cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, we observed a 2-fold increase in the ER signal for Ost1-mCherry in mga2Δ cells (Fig. 5, A and C).

FIGURE 5.

mga2 deletion disrupts general membrane transport. A, anp1-GFP ost1-mCherry (WT) and mga2Δ anp1-GFP ost1-mCherry (mga2Δ) cells were cultured in the presence of oxygen and 0.9% (w/v) BSA for 6 h and imaged by confocal microscopy. These images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar, 5 μm. B, quantification of cells with altered Anp1-GFP localization from A of three biological replicates denoted by different marker symbols. n ≥ 150 cells per replicate. Error bars are mean ± 1 S.D. (**, p < 0.01 by χ2 analysis with Bonferroni correction). C, box-and-whisker quantification of normalized Ost1-mCherry signal intensity from A of n ≥ 300 cells from three biological replicates. Whiskers are the maximum and minimum intensity values (**, p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA and post hoc multiple comparisons with Bonferroni correction). D, Western blot, probed by monoclonal anti-GFP IgG, polyclonal anti-mCherry IgG, and polyclonal anti-Dsc2 IgG (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates from anp1-GFP ost1-mCherry (WT) and mga2Δ anp1-GFP ost1-mCherry (mga2Δ) cells cultured in the presence of oxygen and 0.9% (w/v) BSA for 6 h. E, GFP quantification from D of three biological replicates represented by different marker symbols. The quantity of free GFP was divided by total GFP signal for percent GFP that is free, allowing comparison between lanes and blots. Error bars are 1 S.D. (*, p < 0.05 by paired two-tailed Student's t test, with pairing of WT and mga2Δ data on same blot due to significant interblot variance in WT signal). F, mCherry (mCh) quantification from D of four biological replicates represented by different marker symbols, normalized for loading to Anp1-GFP signal and then normalized to WT signal for comparison between blots. (n.s., no significant difference by paired two-tailed Student's t test).

To determine whether changes in Anp1-GFP and Ost1-mCherry signal were due to changes in protein expression, we probed a Western blot of whole cell lysate from these strains with antibodies against GFP, mCherry, and the loading control Dsc2 (Fig. 5D). In the absence of mga2, we observed a slight decrease in full-length Anp1-GFP signal and an increase in free GFP (Fig. 5, D and E). This suggests that the vacuolar GFP staining observed by microscopy is free GFP from partially degraded Anp1-GFP. We detected no change in Ost1-mCherry expression (Fig. 5, D and F). This indicates that the observed increase in Ost1-mCherry signal in the ER is due to changes in localization rather than changes in expression. These data demonstrate that localization of the Golgi protein Anp1 and the ER protein Ost1 is altered in the absence of mga2. These two proteins are not components of the Sre1 pathway, suggesting that membrane transport is broadly defective in mga2Δ cells.

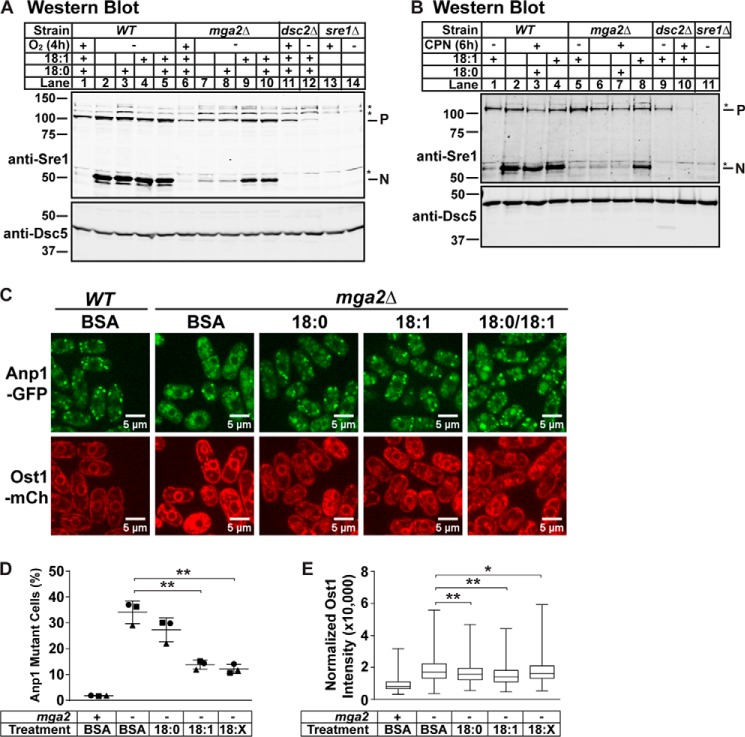

Exogenous Oleate Addition Rescues Sre1 Cleavage and General Membrane Transport in mga2Δ Cells

To examine whether the observed Sre1 cleavage and general membrane transport defects in mga2Δ cells result from defects in fatty acid homeostasis, we tested whether saturated or unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) could rescue Sre1 cleavage in mga2Δ cells under low oxygen and CPN treatment. We assayed Sre1 cleavage with the addition of bovine serum albumin (BSA)-conjugated stearate (18:0), oleate (18:1), or BSA control. WT cells showed robust cleavage under low oxygen that was unaffected by addition of 18:0, 18:1, or both (Fig. 6A, lanes 1–5). Addition of 18:1 alone, but not 18:0, rescued Sre1 cleavage under low oxygen in mga2Δ cells (Fig. 6A, lanes 7–9). Supplementing 18:1 with 18:0 had no additional effect on Sre1 cleavage (Fig. 6A, lane 10). Similarly, preincubation of mga2Δ cells with 18:1, but not 18:0, rescued CPN-induced Sre1 cleavage (Fig. 6B, lane 8). Therefore, addition of exogenous oleate is sufficient to rescue the Sre1 cleavage defect in mga2Δ cells.

FIGURE 6.

Exogenous oleate addition rescues Sre1 cleavage and membrane trafficking in mga2Δ cells. A and B, Western blots, probed with monoclonal anti-Sre1 IgG (5B4) and polyclonal anti-Dsc5 IgG (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h from WT or the indicated mutants grown for 4 h in the presence or absence of oxygen (A) or 6 h in the presence of 200 μm CPN or vehicle (0.12% EtOH, 400 μm NaCl) (B). All lanes contain 0.9% (w/v) BSA, and lanes with supplemental fatty acids conjugated to BSA are indicated. A, BSA-conjugated fatty acids were added at time 0 and were present for 4 h of growth. B, cells were grown overnight with the indicated fatty acid, washed with H2O, and then grown for 6 h with CPN or vehicle. P and N denote precursor and cleaved N-terminal transcription factor forms, respectively. Asterisks (*) indicate nonspecific bands. Blots are representative of three biological replicates. C, anp1-GFP ost1-mCherry (WT) and mga2Δ anp1-GFP ost1-mCherry (mga2Δ) cells were cultured with the indicated fatty acid supplement for 6 h and imaged by confocal microscopy. 18:X indicates supplementation of both 18:0 and 18:1. Experimental data for WT BSA and mga2Δ BSA are the same as reported in Fig. 5, A–C. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar, 5 μm. D, quantification of cells with altered Anp1-GFP localization from C of three biological replicates denoted by different marker symbols. n ≥ 150 cells per replicate. Error bars are mean ± 1 S.D. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by χ2 analysis with Bonferroni correction). E, box-and-whisker quantification of normalized Ost1-mCherry signal intensity from C of n ≥ 300 cells from three biological replicates. Whiskers are the maximum and minimum intensity values. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA and post hoc multiple comparisons with Bonferroni correction). mCh, mCherry.

To test whether alterations in fatty acid composition also cause the observed defects in general membrane transport, we examined Anp1-GFP and Ost1-mCherry localization under parallel conditions. Incubation of mga2Δ cells with 18:1 or both 18:0 and 18:1, but not 18:0 alone, significantly restored Golgi localization of Anp1-GFP, reducing the percentage of mutant cells to 14 and 12%, respectively (Fig. 6, C and D). Similarly, all of the fatty acid treatments significantly reduced Ost1-mCherry intensity in the ER but not to wild-type levels (Fig. 6, C and E). These data suggest that defects in fatty acid homeostasis in mga2Δ cells are responsible for the observed Sre1 cleavage and membrane transport defects.

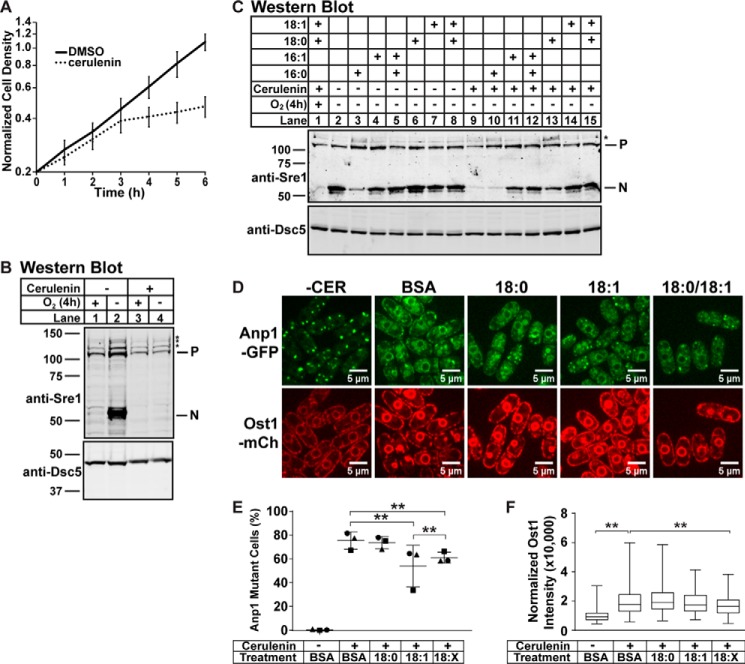

Chemical Inhibition of Fatty Acid Homeostasis Recapitulates mga2Δ Phenotype

After observing rescue of membrane transport and Sre1 cleavage defects by 18:1 in mga2Δ cells (Fig. 6, A and B), we wanted to independently test whether fatty acid homeostasis regulates Sre1 cleavage and membrane transport in WT cells. We were unable to genetically modulate expression of the fatty acid desaturase ole1 by either knockdown or overexpression (data not shown), and no Ole1 inhibitor is available. Instead, we treated WT cells with cerulenin (CER), an irreversible fatty acid synthase inhibitor that affects both saturated fatty acid and UFA homeostasis (21–23). To determine the effects of CER on S. pombe, we grew WT cells with CER or DMSO control for 6 h and measured growth (Fig. 7A). CER inhibited cell division after 3 h of treatment. We then tested the effects of CER on Sre1 cleavage. After 2 h of treatment with CER followed by 4 h of low oxygen treatment without CER, Sre1 cleavage was fully blocked in WT cells (Fig. 7B). Addition of exogenous 16:1 or 18:1 during the 4-h low oxygen treatment rescued this defect, but exogenous 16:0 or 18:0 did not support full cleavage (Fig. 7, C compare lanes 11 and 14 with lanes 10 and 13). Addition of 18:0 and 18:1 together showed cleavage rescue similar to that of 18:1 alone (Fig. 7C, lanes 12 and 15). Therefore, CER treatment recapitulates the Sre1 cleavage defect, and exogenous 18:1 rescues Sre1 cleavage as observed in mga2Δ cells.

FIGURE 7.

Disrupting fatty acid homeostasis blocks general membrane transport and Sre1 cleavage. A, WT cells were grown in liquid culture in 112 nm CER or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO for 6 h. Cell density was measured by absorbance at 600 nm. Data points are the average of four biological replicates. Error bars are 1 S.D. Absorbance at time 0 among the samples ranged from 0.10 to 0.29. To focus on the difference in growth rate between conditions, data were normalized for each sample to a value of 0.2 at time point 0 before averaging. B and C, Western blots, probed with monoclonal anti-Sre1 IgG (5B4) and polyclonal anti-Dsc5 (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h from WT cells. Cells were grown in 112 nm CER or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO for 2 h under normoxia. Cells were then washed, resuspended in fresh medium, and grown without cerulenin for 4 h in the presence or absence of oxygen (B and C) with the indicated BSA-conjugated fatty acid supplemented (C). P and N denote precursor and cleaved N-terminal transcription factor forms, respectively. Asterisks (*) indicate nonspecific bands. Blots are representative of two biological replicates. D, anp1-GFP ost1-mCherry cells were precultured for 1 h in the indicated BSA-conjugated fatty acid. Then 112 nm CER or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO (−CER) was added, and cells were cultured for an additional 3 h before imaging by confocal microscopy. 18:X indicates supplementation of both 18:0 and 18:1. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar, 5 μm. E, quantification of cells with altered Anp1-GFP localization from D of three biological replicates denoted by different marker symbols. n ≥ 100 cells per replicate. Error bars are mean ± 1 S.D. (**, p < 0.01 by χ2 analysis with Bonferroni correction). E, box-and-whisker quantification of normalized Ost1-mCherry signal intensity from D of n ≥ 300 cells from three biological replicates. Whiskers are the maximum and minimum intensity values (**, p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA and post hoc multiple comparisons with Bonferroni correction). mCh, mCherry.

We next examined Golgi localization of Anp1-GFP after 3 h of CER treatment. Anp1-GFP localized to punctate Golgi structures in 99% of control WT cells (Fig. 7, D and E, −CER treatment). However, in CER-treated cells, 75% of cells showed altered Anp1-GFP localization (Fig. 7, D and E, BSA treatment). Addition of exogenous 18:0 had no effect on Anp1-GFP localization, whereas addition of 18:1 or both 18:0 and 18:1 partially rescued Anp1 localization to the Golgi (Fig. 7, D and E). Treatment of cells with cerulenin increased Ost1-mCherry signal 2-fold, and only addition of both 18:0 and 18:1 significantly reduced Ost1-mCherry signal in the ER (Fig. 7, D and F). These data demonstrate that fatty acid homeostasis regulates both membrane transport and Sre1 cleavage in WT cells.

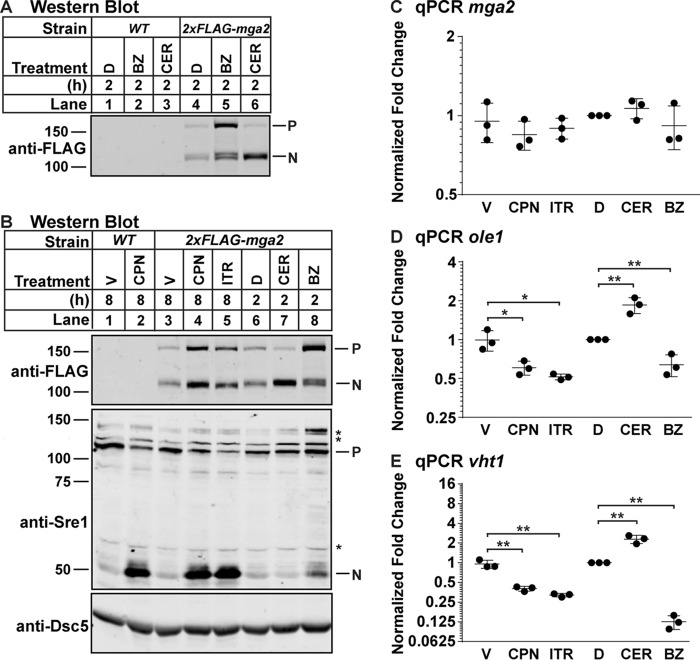

Inhibition of Sterol Synthesis Blocks Mga2 Transcription Factor Activity

Having established that products of the Mga2 transcription factor pathway regulate Sre1 activity, we wanted to test whether products of the Sre1 pathway, namely sterols, regulate Mga2 cleavage and activity. To develop an Mga2 cleavage assay in fission yeast, we N-terminally tagged mga2 at the his3 locus with 2xFLAG to create a construct that allows detection of the full-length, precursor form and the cleaved, active N-terminal transcription factor form. To characterize the function of this fusion protein, we treated WT and 2xFLAG-mga2 cells with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (BZ) or CER and examined Mga2 processing by Western blotting. Treatment of cells with BZ resulted in a strong accumulation of the precursor form and a slower migrating form of the Mga2 N terminus that may represent a ubiquitinylated species seen in S. cerevisiae (12). Conversely, treatment with CER induced Mga2 N terminus accumulation and decreased the precursor form (Fig. 8A). These results were consistent with data in S. cerevisiae showing that the proteasome is required for Mga2 cleavage and that Mga2 activation is regulated by unsaturated fatty acids (11, 12).

FIGURE 8.

Inhibition of sterol synthesis blocks Mga2 transcription factor activity. A, Western blot, probed with monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 IgG and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h from WT and 2xFLAG-mga2 cells grown for 2 h in 0.1% (v/v) DMSO (D), BZ (500 μm), or CER (112 nm). P and N denote precursor and cleaved N-terminal transcription factor forms, respectively. Asterisks denote nonspecific bands. B, Western blot, probed with monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 IgG, monoclonal anti-Sre1 IgG (5B4), and polyclonal anti-Dsc5 IgG (for loading) and imaged by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey CLx, of lysates treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h from WT and 2xFLAG-mga2 cells grown in the following treatments: 8 h in vehicle (0.12% EtOH, 400 μm NaCl; V), CPN (200 μm), or ITR (2 μm) or 2 h in 0.1% (v/v) DMSO (D), BZ (500 μm), or CER (112 nm). P and N denote precursor and cleaved N-terminal transcription factor forms, respectively. Asterisks denote nonspecific bands. C–E, quantitative PCR (qPCR) of the indicated genes of lysates from 2xFLAG-mga2 cells treated as indicated. Error bars are mean ± 1 S.D. of three biological replicates normalized to DMSO treatment (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by two-tailed Student's t test).

To test whether sterols have an effect on Mga2 cleavage and activity, we treated 2xFLAG-mga2 cells with the statin CPN or the lanosterol 14α-demethylase inhibitor itraconazole (ITR) alongside CER and BZ treatment controls and assayed Mga2 processing and target gene expression. CPN and ITR treatment caused accumulation of both the Mga2 precursor and N-terminal transcription factor, but the ratio of the two forms remained the same (Fig. 8B, lanes 3–5). Although the overall amount of Mga2 protein appears to change among these different treatments, there was no change in mga2 expression (Fig. 8, B and C), indicating that the increase in Mga2 protein results from a post-transcriptional mechanism. Importantly, treatment of 2xFLAG-mga2 cells with CPN induced Sre1 cleavage to the same level as in WT cells (Fig. 8B, lane 2 versus 4), confirming that this tagged protein is functional. Consistent with the observed changes in Mga2 N terminus accumulation, CER treatment induced expression of the Mga2 target genes ole1 and vht1, whereas treatment with BZ reduced expression to levels seen in mga2Δ cells (Fig. 8, D and E) (9). Interestingly, despite the increase in Mga2 N terminus accumulation in CPN- and ITR-treated cells, ole1 expression was reduced to the basal level seen with BZ treatment (Fig. 8D). Likewise, inhibition of sterol synthesis reduced vht1 expression (Fig. 8E). These data demonstrate that the 2xFLAG-mga2 fusion protein is functional and that Mga2 activation is regulated by fatty acids and requires the proteasome in S. pombe. Furthermore, Mga2 transcriptional activity requires sterol synthesis.

Discussion

Taken as a whole, the data in this study show that unsaturated fatty acids regulate Sre1 transcription factor activation in S. pombe. Disrupting fatty acid homeostasis, either through deletion of the mga2 transcription factor, which regulates fatty acid desaturation and TAG and GPL synthesis, or through treatment with the fatty acid synthase inhibitor CER, blocked induction of Sre1 cleavage by sterols or low oxygen (Figs. 1 and 7B) (9). Importantly, the Sre1 cleavage defects in both mga2Δ and CER-treated cells were rescued by addition of exogenous 18:1, indicating that UFA regulates Sre1 cleavage and that a defect in fatty acid homeostasis is responsible for the Sre1 cleavage defect (Figs. 6, A and B, and 7C). Interestingly, the Sre1 cleavage defect that results from CER treatment of WT cells was more fully rescued by UFA than that observed in the absence of mga2 (Fig. 6, A and B, versus Fig. 7C). This is likely due to the fact that CER specifically inhibits fatty acid synthesis, whereas mga2 regulates a number of other lipid homeostasis pathways (9).

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that SREBP cleavage is disrupted due to a kinetic defect in the membrane transport component of the SREBP activation pathway when fatty acid homeostasis is disrupted. First, the observed Sre1 cleavage defect is largely a failure to induce cleavage under low oxygen conditions and is magnified by positive feedback within the system (Figs. 1 and 2), suggesting that the disruption in the absence of mga2 is incomplete and therefore more likely a kinetic defect than a complete block in cleavage. Second, overexpression of the Sre1 binding and trafficking partner Scp1 increased Sre1 cleavage in mga2Δ cells to a similar extent as WT cells, suggesting that the Sre1 cleavage defect in these cells can be bypassed and occurs at a step after Sre1-Scp1 complex formation (Fig. 3C). Third, the Sre1 homolog Sre2 also exhibited a cleavage defect in the absence of mga2, indicating a shared deficiency between these two pathways, which do not share Scp1 (Fig. 3, D and E). Fourth, the Dsc E3 ligase was functional in mga2Δ cells, supporting the existence of a defect prior to cleavage at the Golgi and narrowing the defective step to transport of pathway components (Fig. 4). Finally, mga2 deletion or treatment of WT cells with the fatty acid synthesis inhibitor CER altered the localization of the Golgi-resident protein Anp1 and the ER-resident protein Ost1 (Figs. 5 and 7D), indicating a general membrane transport defect when fatty acid homeostasis is disrupted. Both the Sre1 cleavage defects and the Anp1/Ost1 localization defects were rescued by addition of unsaturated fatty acid (Figs. 6 and 7). It is probable that the other members of the SREBP activation pathway are affected by these same membrane transport defects. Together, these data suggest that the observed Sre1 cleavage defects are due to membrane transport defects.

Interestingly, the rescue of the Sre1 cleavage defect with exogenous 18:1 was more robust than the rescue of Anp1 and Ost1 localization (Figs. 6 and 7). These observations suggest that both the defects and rescue observed for membrane transport in these systems are small but that they have a large effect on Sre1 N terminus accumulation. This is consistent with our observation that positive feedback in the system amplifies the small defect in membrane transport and that in the absence of this positive feedback Sre1 cleavage only decreases 1.5-fold (Fig. 2). Alternatively, if multiple Sre1 pathway components are negatively affected by the membrane transport defect, then small improvements in transport of all of those pathway components could combine to produce a larger improvement in Sre1 cleavage. We favor a model that incorporates both of these possibilities.

Although this study did not identify the precise step in membrane transport affected by fatty acid supply, membrane dynamics are highly sensitive to the lipid composition of the cell, and alterations in lipid composition have wide ranging effects, including on protein trafficking. Generally, increased saturated phospholipids, sterols, and sphingolipids result in more tightly packed, less fluid membranes, whereas phospholipid desaturation results in less densely packed, more fluid membranes (18). One possible source of the observed membrane transport defect that affects Sre1 and Sre2 cleavage is during COPII vesicle budding from the ER. Liposomes composed of diunsaturated glycerophospholipids form more COPII vesicles in vitro than liposomes composed of monounsaturated glycerophospholipids (25). This suggests that increasing saturated phospholipids reduces vesicle budding. Consistent with our study, treatment of S. cerevisiae with cerulenin blocked secretory protein transport from the transitional ER to the Golgi (26). Membrane curvature and saturation are also important for vesicle targeting to the appropriate cellular compartment. Diunsaturated phospholipids with bulky headgroups favor membrane curvature, whereas sterols disfavor curvature (27). In mammalian cells, small artificial liposomes containing diunsaturated phospholipids bound to the Golgi more strongly than liposomes containing monounsaturated or saturated phospholipids, and binding also decreased with increasing liposome size (28). Because the Dsc E3 ligase showed some accumulation in the ER, mga2Δ cells are most likely defective in ER exit, although we cannot rule out additional effects on vesicle targeting and fusion to the Golgi.

In our previous report, we highlighted similarities between Mga2 and Sre1 regulation of lipid homeostasis in fission yeast and SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 regulation of lipid homeostasis in mammalian cells. Both Mga2 and SREBP-1 regulate TAG and GPL biosynthesis, most notably through the regulation of stearoyl-CoA desaturases (ole1 in S. pombe and SCD1 in mammals) (9, 29). Likewise, both Sre1 and SREBP-2 regulate sterol biosynthesis (1, 30). Although regulation of mammalian SREBPs by sterols is well understood, how fatty acids regulate SREBPs is less clear (31–34). On the one hand, reports suggest that exogenous polyunsaturated fatty acids negatively regulate SREBP-1 cleavage (35–38). Another study showed that exogenous 18:1 does not impact SREBP cleavage under normal culture conditions but rather potentiates inhibition of cleavage by exogenous sterols (39). On the other hand, others report a failure to induce SREBP-1 in the absence of SCD1, indicating that fatty acid desaturation is required for SREBP-1 activation (29). It will be important to continue this line of inquiry in the mammalian system to better understand the regulation of SREBPs by fatty acids and glycerophospholipids.

Membrane fluidity affects multiple cellular functions ranging from secretion to apoptosis (40). Programmed co-regulation and coordination of sterol synthesis and TAG/GPL synthesis is necessary for maintenance of membrane fluidity. Despite parallels between the mammalian and yeast pathways, a crucial difference exists in how these cells coordinate sterol and TAG/GPL synthesis. In mammalian cells, SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 are activated by the same proteases and have a shared requirement for ER-to-Golgi transport by the Scp1 homolog SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP), providing an opportunity for strict balance of these related metabolic pathways (30). In contrast, although both Mga2 and Sre1 are synthesized as membrane-anchored proteins, their mechanisms of activation are distinct, raising the question of how their activities are coordinated.

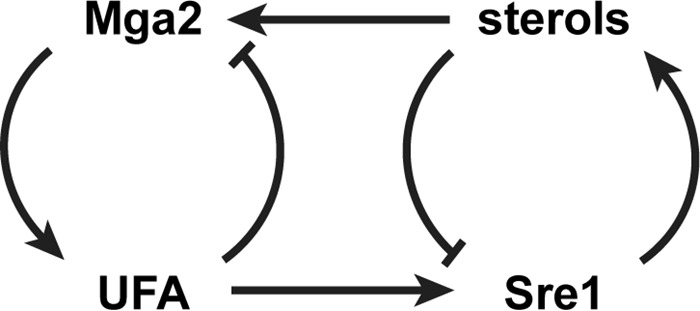

Given the results presented here, we propose that regulation of Sre1 cleavage by unsaturated fatty acids (the products of Mga2 activity) and regulation of Mga2 cleavage by sterols (the products of Sre1 activity) are one mechanism for coordinating these two interdependent pathways in fission yeast (Fig. 9). Interestingly, Covino et al. (14) showed that sterols increased membrane order and stabilized S. cerevisiae Mga2 in an active conformation in vitro. In S. pombe, we observed an accumulation of Mga2 protein when sterol synthesis was inhibited with CPN or ITR (Fig. 8B). However, rather than induce expression of Mga2 target genes, CPN and ITR inhibited ole1 and vht1 expression to levels seen in mga2Δ cells (Fig. 8, D and E) (9). Thus, Mga2 activity requires sterol synthesis. Understanding how sterols regulate Mga2 activity and protein levels will be the focus of future studies.

FIGURE 9.

Model of coordination of Mga2 and Sre1 pathways. Sterol and TAG/GPL lipid biosynthetic pathways are positively regulated by the transcription factors Sre1 and Mga2, respectively. Both Sre1 and Mga2 are product-inhibited, Sre1 by sterols and Mga2 by UFA. Mga2 regulates Sre1 through the requirement for UFA, and Sre1 regulates Mga2 through the requirement of sterols for Mga2 activity.

Collectively, these results outline a model in which both Mga2 and Sre1 are feedback-inhibited by their respective products but are also regulated by products of the other pathway (Fig. 9). In this way, both arms of lipid synthesis communicate, and the pathways can act in balance. Although our results suggest that cross-talk exists, further studies are needed to demonstrate the role for this regulatory network in physiological control of lipid homeostasis.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

General chemicals and materials were obtained from Sigma or Fisher. Other sources include yeast extract, peptone, and agar from BD Biosciences; digitonin from EMD Chemicals; brefeldin A, compactin, itraconazole, cerulenin, Igepal CA-630 (Nonidet P-40), amino acid supplements, and 1× protease inhibitors (PI) (10 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 0.5 μm PMSF) from Sigma; bortezomib from LC Laboratories; alkaline phosphatase (catalog number 713023) and complete EDTA-free PI from Roche Applied Sciences; Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase from New England Biolabs; RNA STAT-60 from Tel-Test; GoTaq qPCR Master Mix from Promega; oligonucleotides from Integrated DNA Technologies; horseradish peroxidase-conjugated, affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; IRDye donkey anti-rabbit and donkey anti-mouse from LI-COR Biosciences; Myc monoclonal 9E10 IgG and β-actin monoclonal C4 IgG from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; anti-Myc polyclonal IgG (catalog number 06-549) from Upstate Biotechnology; anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal IgG from Sigma (F1804); anti-GFP monoclonal IgG from Roche Applied Science (1814460); anti-mCherry polyclonal IgG from Invitrogen (PA5-34974); prestained protein standards from Bio-Rad; protein G magnetic beads from New England Biolabs; protein A-Sepharose from GE Healthcare; and fatty acid-free BSA from SeraCare Life Sciences.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-Sre1 IgG (aa 1–260) was generated using a standard protocol as described previously (1). Briefly, antigen was expressed in Escherichia coli and affinity-purified by an N-terminal polyhistidine tag. Sre1-specific antibodies were isolated from rabbit serum by affinity to the polyhistidine-tagged Sre1 antigen. Specificity of this antibody was assayed by loss of immunoreactivity in an sre1Δ strain. We generated rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-Sre2 IgG (aa 1–426) using a standard protocol as described above for anti-Sre1 (1).

We generated monoclonal antibody 5B4 IgG1κ to Sre1 (aa 1–260) as described previously using recombinant protein that was purified from E. coli by nickel affinity chromatography (Qiagen) and injected into BALB/c mice (9). Antibody specificity was tested by immunoblotting against S. pombe extracts from cells overexpressing sre1.

Generation of polyclonal antibodies to Dsc E3 ligase complex members 1–5 (Dsc1–Dsc5) was described previously (5, 6). Hexahistidine-tagged recombinant protein antigens Dsc1 (aa 20–319), Dsc2 (aa 250–372), Dsc3 (aa 1–190), Dsc4 (aa 150–281), and Dsc5 (aa 251–427) were purified from E. coli using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Qiagen). Dsc1–5 antisera were generated by Covance using a standard protocol. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugation of Dsc2–Dsc5 antisera was performed using the Thermo Scientific (Pierce) EZ-link Plus Activated Peroxidase kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. HRP conjugation of Dsc1 antiserum was performed using the One-Hour Western Detection System (GenScript).

Monoclonal antibodies to His6-Scp1 (aa 446–544) were made using recombinant protein that was purified from E. coli by nickel affinity chromatography (Qiagen) as described previously (17). Antibody specificity of the final clones was tested by immunoblotting against S. pombe extracts from cells overexpressing scp1. 8G4C11 (IgG1k), 1G1D6 (IgG2ak), and 7B4A3 (IgG1k) were mixed for Western blotting. Antiserum to Cdc48 was the kind gift of R. Hartmann-Petersen (University of Copenhagen) (41).

Yeast Culture

Yeast strains are described in Table 1. S. pombe were cultured to exponential phase at 30 °C in rich YES medium (0.5% (w/v) yeast extract plus 3% (w/v) glucose supplemented with 225 μg/ml each of uracil, adenine, leucine, histidine, and lysine (42)) unless otherwise indicated. For fatty acid supplementation, fatty acids were added to 1 mm in YES medium from a 12.7 mm stock in 12% (w/v) fatty acid-free BSA. Fatty acids were conjugated to fatty acid-free BSA as described previously (9). Brefeldin A was added from a stock concentration of 5 mg/ml EtOH to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml in 2% EtOH. Compactin was added to a final concentration of 200 μm from a 10 mm stock in 6% EtOH, 20 mm NaCl. Cerulenin was added to a final concentration 112 nm in medium from a 1000× stock in DMSO.

TABLE 1.

S. pombe strain list

| Strains | Genotype | Source/Ref. | Figs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| KGY425 | h− leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 | ATCC | 1–4, 6–8 |

| PEY1762 | h− leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 Δmga2-D1::kanMX6 | Burr et al. (9) | 1–4, 6 |

| PEY1792 | h+ leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 Δdsc2-D1::kanMX6 | This study | 1, 3, 4, 6 |

| PEY522 | h− leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 Δsre1-D1::kanMX6 | Hughes et al. (1) | 1–4, 6 |

| PEY888 | h− leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 sre1-MP (mutant promoter) | Hughes et al. (16) | 2 |

| PEY1793 | h+ leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 sre1-MP Δmga2-D1::kanMX6 | This study | 2 |

| PEY553 | h− leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 Δsre2-D1::kanMX6 | Hughes et al. (1) | 3 |

| PEY554 | h− leu1–32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 his3-D1 Δscp1-D1::kanMX6 | Hughes et al. (1) | 3 |

| PEY546 | h− ura4-D18 leu1–32 his3-D1 ade6-M210 scp1–13xmyc::kanMX6 | Burg et al. (44) | 3 |

| PEY1796 | h+ ura4-D18 leu1–32 his3-D1 ade6-M210 scp1–13xmyc::kanMX6 Δmga2-D1::natMX6 | This study | 3 |

| PEY1569 | h+ Δdsc1-D1::kanMX6 | This study | 3, 4 |

| PEY1797 | h+ leu1–32 his3-D1 ade6-M216 anp1-GFP::ura4+, ost1-mCherry::ura4+ | This study | 5–7 |

| PEY1798 | h− leu1–32 his3-D1 ade6-M216 Δmga2-D1::kanMX6, anp1-GFP::ura4+, ost1-mCherry::ura4+ | This study | 5, 6 |

| PEY1799 | h+ leu1–32 ade6-M216 Δmga2-D1::kanMX6, his3::2xFLAG-mga2-his3+ | This study | 8 |

Sre1 Cleavage Assay

Cells were grown in YES medium to exponential phase inside an InVivo2 400 hypoxic work station (Biotrace, Inc.) and harvested for protein extraction and immunoblotting. Cell pellets were resuspended in 17 μl of 1.85 m NaOH, 7.4% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol and vortexed. Samples were incubated on ice for 10 min. TCA was added to a final concentration of 30% (w/v), and the samples were vortexed and incubated on ice for 10 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was washed with cold acetone. Samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and dried completely under vacuum. Pellets were resuspended in 150 μl of SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1× protease inhibitors) and sonicated for 10 s. Protein was quantified using the BCA protein assay (Pierce). For alkaline phosphatase treatment, lysate was diluted at least 1:2 in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and then alkaline phosphatase was added to 20% (v/v). Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. SDS-polyacrylamide gels were loaded evenly for total protein, and consistent loading was confirmed following electroblotting by staining the membrane with Ponceau S. Blots were imaged using enhanced chemiluminescence and film or the Odyssey CLx infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences) as noted in the figure legends.

Dsc2 Immunoprecipitation

Exponentially growing cells (5 × 108) were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation as described previously (43). Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of digitonin lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 50 mm KOAc, 2 mm MgOAc, 1 mm CaCl2, 200 mm sorbitol, 1 mm NaF, 0.3 mm Na3VO4, 1% (w/v) digitonin, 2× PI, 1× Complete EDTA-free PI). Cells were lysed by bead beating for 10 min at 4 °C, and then beads were washed with 800 μl of digitonin lysis buffer to collect all lysate. The lysate was incubated with rotation for 40 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged for 10 min at 100,000 × g to pellet insoluble material. 1.3 mg of supernatant protein was incubated with 10 μl of anti-Dsc2 antiserum for 15 min and then incubated with 80 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads overnight at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times with digitonin lysis buffer, and the bound fraction was eluted into SDS lysis buffer + 1× PI and 1× loading dye (30 mm Tris-HCl, 3% SDS, 5% glycerol, 0.004% bromphenol blue, 2.5% 2-mercaptoethanol) at 95 °C for 5 min.

Dsc1 Glycosylation Assay

Exponentially growing cells (2.5 × 108) were collected and resuspended in 300 μl of B88 buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mm KOAc, 5 mm Mg(OAc)2, 250 mm sorbitol) + 1× protease inhibitors and 1× Complete EDTA-free PI. Cells were lysed using glass beads for 12 min and then centrifuged for 5 min at 500 × g to clear cell debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min, and the pelleted membranes were resuspended in 100 μl of B88 buffer with 1% Nonidet P-40 (v/v). The membranes were solubilized at 4 °C for 1 h, then samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected as detergent-solubilized membrane. Loading dye was added, and samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h before running SDS-PAGE. At no time were samples boiled as Dsc1 aggregates at high temperature.

Microsome Preparation for Scp1 Immunoblotting

Cell pellets from exponentially growing cells (5 × 107) were resuspended in 50 μl of B88 buffer + 2× PI. Cells were lysed by bead beating for 10 min with 200 μl of glass beads at 4 °C. Beads were washed with 500 μl of B88 buffer + 1× PI, and the lysate was transferred to a new tube. The lysate was centrifuged for 5 min at 500 × g at 4 °C. 80% of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000 × g at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the microsome pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of SDS lysis buffer + 1× PI + 1× DTT. Microsomes were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before BCA assay. Samples were diluted 1:2 with urea buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 6 m urea, 2% SDS) and 1× loading dye before loading for SDS-PAGE.

Scp1-13xMyc Immunoprecipitation

Cell pellets from exponentially growing cells (5 × 108) were resuspended in 200 μl of Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40 (v/v), 2× PI, 2× Complete EDTA-free PI). Cells were lysed by bead beating for 10 min at 4 °C, and then beads were washed with 800 μl of Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer to collect all lysate. The lysate was incubated with rotation for 40 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged for 5 min at 500 × g to clear intact cells and nuclei. 3 mg of supernatant protein was incubated with 4 μg of anti-Myc 9E10 IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 15 min and then incubated with 80 μl of protein G magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) for 2 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer, and the bound fraction was eluted into SDS lysis buffer + 1× PI and 1× loading dye at 95 °C for 5 min.

Fluorescence Microscopy

S. pombe cells expressing fluorescently tagged proteins were imaged on 2% agarose pads using an AxioObserver.Z1 inverted microscope (Zeiss) with a Yokogawa CSU22 high speed spinning Nipkow disk with microlenses (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc.), three >40-milliwatt solid state lasers (473, 561, and 658 nm), and a Cascade II electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Roper Scientific/Photometrics). Images were captured using a 100× oil objective and SlideBook software for data acquisition (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc.). Images were analyzed using NIH ImageJ software. All images were acquired and processed in an identical manner. For each frame, a Z-stack was captured of five slices 0.2 μm apart.

For analysis of microscopy data for Anp1-GFP localization, each slice was evaluated independently, and quantification data from all slices were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation. For statistical analysis, we divided the number of cells by 5 to account for the 5× sampling of each cell during analysis of all Z-slices. This method conservatively underestimated the number of mutant cells in any frame as a truly mutant cell may appear mutant in one Z-slice and WT in another. For quantification, cells were divided into two bins: WT (Golgi localization of Anp1, appearing as punctate signal with no ER staining around the nucleus or periphery) and mutant (three different phenotypes: no specific signal, ER signal only, and both ER and Golgi signals). For each experiment, we performed pairwise χ2 analysis of all treatments (28 comparisons) and a post hoc Bonferroni correction.

For analysis of microscopy data for Ost1-mCherry signal intensity, the middle Z-slice was selected from each frame, and all images were normalized for overall signal. A straight line was drawn along the long axis of each cell through the nucleus, and the maximum and minimum signal intensity values were recorded. To normalize for comparison between biological replicates and cell background, the minimum value was subtracted from the maximum value to get the normalized Ost1-mCherry intensity. Experimental data are represented by box-and-whisker plot with the midline the median and the whiskers extending to the largest and smallest values. Experiments were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc multiple comparison of means between all of the treatments and Bonferroni correction.

Author Contributions

R. B. designed and conducted the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. E. V. S. conducted preliminary experiments. P. J. E. conceived the project, designed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Mutchler (University of Massachusetts, Boston) for advice on statistical analysis and S. Zhao and other members of the Espenshade laboratory for help and advice.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL077588 (to P. J. E.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- TAG

- triacylglycerol

- GPL

- glycerophospholipid

- Sre1N

- Sre1 N-terminal transcription factor fragment

- Sre2N

- Sre2 N terminus

- PI

- protease inhibitors

- YES

- yeast extract plus supplements

- CPN

- compactin

- ITR

- itraconazole

- UFA

- unsaturated fatty acid

- CER

- cerulenin

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- BZ

- bortezomib

- aa

- amino acids

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- MP

- mutant promoter

- COPII

- coat protein complex II.

References

- 1. Hughes A. L., Todd B. L., and Espenshade P. J. (2005) SREBP pathway responds to sterols and functions as an oxygen sensor in fission yeast. Cell 120, 831–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Todd B. L., Stewart E. V., Burg J. S., Hughes A. L., and Espenshade P. J. (2006) Sterol regulatory element binding protein is a principal regulator of anaerobic gene expression in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2817–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Summons R. E., Bradley A. S., Jahnke L. L., and Waldbauer J. R. (2006) Steroids, triterpenoids and molecular oxygen. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361, 951–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Porter J. R., Burg J. S., Espenshade P. J., and Iglesias P. A. (2010) Ergosterol regulates sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) cleavage in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41051–41061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stewart E. V., Nwosu C. C., Tong Z., Roguev A., Cummins T. D., Kim D. U., Hayles J., Park H. O., Hoe K. L., Powell D. W., Krogan N. J., and Espenshade P. J. (2011) Yeast SREBP cleavage activation requires the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase complex. Mol. Cell 42, 160–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stewart E. V., Lloyd S. J., Burg J. S., Nwosu C. C., Lintner R. E., Daza R., Russ C., Ponchner K., Nusbaum C., and Espenshade P. J. (2012) Yeast sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) cleavage requires Cdc48 and Dsc5, a ubiquitin regulatory X domain-containing subunit of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 672–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim J., Ha H. J., Kim S., Choi A. R., Lee S. J., Hoe K. L., and Kim D. U. (2015) Identification of Rbd2 as a candidate protease for sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) cleavage in fission yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 468, 606–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raychaudhuri S., and Espenshade P. J. (2015) Endoplasmic reticulum exit of Golgi-resident defective for SREBP cleavage (Dsc) E3 ligase complex requires its activity. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 14430–14440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burr R., Stewart E. V., Shao W., Zhao S., Hannibal-Bach H. K., Ejsing C. S., and Espenshade P. J. (2016) Mga2 transcription factor regulates an oxygen-responsive lipid homeostasis pathway in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 12171–12183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kandasamy P., Vemula M., Oh C. S., Chellappa R., and Martin C. E. (2004) Regulation of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces: the endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein, Mga2p, a transcription activator of the OLE1 gene, regulates the stability of the OLE1 mRNA through exosome-mediated mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36586–36592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiang Y., Vasconcelles M. J., Wretzel S., Light A., Gilooly L., McDaid K., Oh C. S., Martin C. E., and Goldberg M. A. (2002) Mga2p processing by hypoxia and unsaturated fatty acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: impact on LORE-dependent gene expression. Eukaryot. Cell 1, 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoppe T., Matuschewski K., Rape M., Schlenker S., Ulrich H. D., and Jentsch S. (2000) Activation of a membrane-bound transcription factor by regulated ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent processing. Cell 102, 577–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang S., Skalsky Y., and Garfinkel D. J. (1999) MGA2 or SPT23 is required for transcription of the delta9 fatty acid desaturase gene, OLE1, and nuclear membrane integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 151, 473–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Covino R., Ballweg S., Stordeur C., Michaelis J. B., Puth K., Wernig F., Bahrami A., Ernst A. M., Hummer G., and Ernst R. (2016) A eukaryotic sensor for membrane lipid saturation. Mol. Cell 63, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown M. S., Faust J. R., Goldstein J. L., Kaneko I., and Endo A. (1978) Induction of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductase-activity in human fibroblasts incubated with compactin (Ml-236B), a competitive inhibitor of reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 1121–1128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughes B. T., Nwosu C. C., and Espenshade P. J. (2009) Degradation of SREBP precursor requires the ERAD components UBC7 and HRD1 in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20512–20521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hughes A. L., Stewart E. V., and Espenshade P. J. (2008) Identification of twenty-three mutations in fission yeast Scap that constitutively activate SREBP. J. Lipid Res. 49, 2001–2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lande M. B., Donovan J. M., and Zeidel M. L. (1995) The relationship between membrane fluidity and permeabilities to water, solutes, ammonia, and protons. J. Gen. Physiol. 106, 67–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brenner R. R. (1984) Effect of unsaturated acids on membrane structure and enzyme kinetics. Prog. Lipid Res. 23, 69–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Los D. A., and Murata N. (2000) Regulation of enzymatic activity and gene expression by membrane fluidity. Sci. STKE 2000, pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Omura S. (1976) The antibiotic cerulenin, a novel tool for biochemistry as an inhibitor of fatty acid synthesis. Bacteriol. Rev. 40, 681–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vance D., Goldberg I., Mitsuhashi O., and Bloch K. (1972) Inhibition of fatty acid synthetases by the antibiotic cerulenin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 48, 649–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Awaya J., Ohno T., Ohno H., and Omura S. (1975) Substitution of cellular fatty acids in yeast cells by the antibiotic cerulenin and exogenous fatty acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 409, 267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matynia A., Salus S. S., and Sazer S. (2002) Three proteins required for early steps in the protein secretory pathway also affect nuclear envelope structure and cell cycle progression in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 115, 421–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsuoka K., Orci L., Amherdt M., Bednarek S. Y., Hamamoto S., Schekman R., and Yeung T. (1998) COPII-coated vesicle formation reconstituted with purified coat proteins and chemically defined liposomes. Cell 93, 263–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shindiapina P., and Barlowe C. (2010) Requirements for transitional endoplasmic reticulum site structure and function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1530–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McMahon H. T., and Boucrot E. (2015) Membrane curvature at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 128, 1065–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Magdeleine M., Gautier R., Gounon P., Barelli H., Vanni S., and Antonny B. (2016) A filter at the entrance of the Golgi that selects vesicles according to size and bulk lipid composition. eLife 5, e16988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miyazaki M., Dobrzyn A., Man W. C., Chu K., Sampath H., Kim H. J., and Ntambi J. M. (2004) Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 gene expression is necessary for fructose-mediated induction of lipogenic gene expression by sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25164–25171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Horton J. D. (2002) Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins: transcriptional activators of lipid synthesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30, 1091–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vallett S. M., Sanchez H. B., Rosenfeld J. M., and Osborne T. F. (1996) A direct role for sterol regulatory element binding protein in activation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 12247–12253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lopez J. M., Bennett M. K., Sanchez H. B., Rosenfeld J. M., and Osborne T. F. (1996) Sterol regulation of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase: a mechanism for coordinate control of cellular lipid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 1049–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Magaña M. M., and Osborne T. F. (1996) Two tandem binding sites for sterol regulatory element binding proteins are required for sterol regulation of fatty-acid synthase promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 32689–32694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bennett M. K., Lopez J. M., Sanchez H. B., and Osborne T. F. (1995) Sterol regulation of fatty acid synthase promoter. Coordinate feedback regulation of two major lipid pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25578–25583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Worgall T. S., Sturley S. L., Seo T., Osborne T. F., and Deckelbaum R. J. (1998) Polyunsaturated fatty acids decrease expression of promoters with sterol regulatory elements by decreasing levels of mature sterol regulatory element-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 25537–25540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee J. N., Zhang X., Feramisco J. D., Gong Y., and Ye J. (2008) Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit proteasomal degradation of Insig-1 at a postubiquitination step. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33772–33783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hannah V. C., Ou J., Luong A., Goldstein J. L., and Brown M. S. (2001) Unsaturated fatty acids down-regulate SREBP isoforms 1a and 1c by two mechanisms in HEK-293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4365–4372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Takeuchi Y., Yahagi N., Izumida Y., Nishi M., Kubota M., Teraoka Y., Yamamoto T., Matsuzaka T., Nakagawa Y., Sekiya M., Iizuka Y., Ohashi K., Osuga J., Gotoda T., Ishibashi S., et al. (2010) Polyunsaturated fatty acids selectively suppress sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 through proteolytic processing and autoloop regulatory circuit. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11681–11691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thewke D. P., Panini S. R., and Sinensky M. (1998) Oleate potentiates oxysterol inhibition of transcription from sterol regulatory element-1-regulated promoters and maturation of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21402–21407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Melser S., Molino D., Batailler B., Peypelut M., Laloi M., Wattelet-Boyer V., Bellec Y., Faure J. D., and Moreau P. (2011) Links between lipid homeostasis, organelle morphodynamics and protein trafficking in eukaryotic and plant secretory pathways. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 177–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hartmann-Petersen R., Wallace M., Hofmann K., Koch G., Johnsen A. H., Hendil K. B., and Gordon C. (2004) The Ubx2 and Ubx3 cofactors direct Cdc48 activity to proteolytic and nonproteolytic ubiquitin-dependent processes. Curr. Biol. 14, 824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moreno S., Klar A., and Nurse P. (1991) Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194, 795–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lloyd S. J., Raychaudhuri S., and Espenshade P. J. (2013) Subunit architecture of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase required for sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) cleavage in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 21043–21054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burg J. S., Powell D. W., Chai R., Hughes A. L., Link A. J., and Espenshade P. J. (2008) Insig regulates HMG-CoA reductase by controlling enzyme phosphorylation in fission yeast. Cell Metab. 8, 522–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]