Abstract

There is an increased demand for comprehensive analysis of vitamin D metabolites. This is a major challenge, especially for 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1α,25(OH)2VitD], because it is biologically active at picomolar concentrations. 4-Phenyl-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione (PTAD) was a revolutionary reagent in dramatically increasing sensitivity of all diene metabolites and allowing the routine analysis of the bioactive, but minor, vitamin D metabolites. A second generation of reagents used large fixed charge groups that increased sensitivity at the cost of a deterioration in chromatographic separation of the vitamin D derivatives. This precludes a survey of numerous vitamin D metabolites without redesigning the chromatographic system used. 2-Nitrosopyridine (PyrNO) demonstrates that one can improve ionization and gain higher sensitivity over PTAD. The resulting vitamin D derivatives facilitate high-resolution chromatographic separation of the major metabolites. Additionally, a liquid-liquid extraction followed by solid-phase extraction (LLE-SPE) was developed to selectively extract 1α,25(OH)2VitD, while reducing 2- to 4-fold ion suppression compared with SPE alone. LLE-SPE followed by PyrNO derivatization and LC/MS/MS analysis is a promising new method for quantifying vitamin D metabolites in a smaller sample volume (100 µL of serum) than previously reported methods. The PyrNO derivatization method is based on the Diels-Alder reaction and thus is generally applicable to a variety diene analytes.

Keywords: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; major vitamin D metabolites; matrix effect; smaller sample volume; quantification

In 1943, vitamin D was recommended as an essential nutrient for the US public. People can acquire the precursors to the bioactive forms, vitamin D3 and vitamin D2, from diet, supplements, and sunlight. In the liver, both forms of vitamin D are rapidly hydroxylated to corresponding 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)VitD]. Being a predominant metabolite, circulating 25(OH)VitD serves as the preferred surrogate biomarker of vitamin D nutritional status (1, 2). Low levels of 25(OH)VitD indicate low vitamin D nutritional intake, which is related to many diseases, such as osteomalacia, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, asthma, and other health risks, including muscle weakness, diabetes, and cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s disease (3–7). Consequently, analytical techniques for measurement of 25(OH)VitD have been developed (8–12). In the kidney, 25(OH)VitD is further hydroxylated to 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1α,25(OH)2VitD]. 1α,25(OH)2VitD is the major biologically active metabolite and plays an important role in decreasing the risk of many diseases, including common cancers, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease, and chronic kidney disease (13–17). Most recently, we have demonstrated that 1α,25(OH)2VitD also appears to be important for the health of the eye (18). The influence that these biologically active forms of vitamin D have on these numerous diseases and associated organ systems has significantly increased scientific interest in their quantitative analysis (19–25).

Among the numerous analytical measurement techniques, Food and Drug Administration-approved DiaSorin RIA and Liaison assays (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN) are the most widely used for quantifying 25(OH)VitD and other nonhydroxylated vitamin D metabolites, but do not include 1α,25(OH)2VitD. Furthermore, the accuracy and precision of these assays are unsatisfactory (26–28). Therefore, the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey recommended liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) as the best method for quantifying vitamin D metabolites due to improved sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility (29). The 25(OH)VitD3 is present at relatively high levels (50–125 nM) in human serum and thus can be accurately quantified by LC/MS/MS (30). Additionally, a 25(OH)VitD test is included in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program, set up to assure accurate and reliable clinical measurements. By contrast, the 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 is challenging to directly quantify using LC/MS/MS. One challenge associated with 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 quantification is that its human serum concentration ranges from 35 to 150 pmol/l (14–60 pg/ml), approximately 1,000-fold lower than 25(OH)VitD3 (31). This serum concentration is significantly lower than the general instrumental detection limit of conventional LC/MS/MS methods. Second, the poor ionization efficiency of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 further weakens the advantage of LC/MS/MS methods. Finally, less-than-optimal sample preparation techniques may cause high ion suppression and loss of the targeted analytes. To overcome these challenges, accurately measuring 1α,25(OH)2VitD requires both a superior sample preparation method and a selective derivatization reagent to achieve good recovery and increased ionization efficiency, respectively. In previous studies, solid-phase extraction (SPE) sample preparation followed by 4-phenyl-1,2,4-triazole-3,5-dione (PTAD) derivatization proved to be a relatively more comprehensive, accurate, and sensitive method for quantitative analysis of major vitamin D metabolites (21, 22, 32). However, it is still difficult to quantify the low endogenous levels of 1α,25(OH)2VitD in small sample volumes. In an attempt to further increase the method sensitivity, new effective dienophiles, 4-(4′-dimethylaminophenyl)-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione; 4-[2-(3,4-dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-4-methyl-3-oxo-2-quinoxalinyl)ethyl]-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3,5(4H)-dione; and other “triazoline-diones,” have been developed (25, 33–37). Among them, the positively charged derivatization reagent, Amplifex-Diene and SecoSET, are reported to have a 10-fold ioniziation efficiency improvement over PTAD (25, 36, 38). Compared with PTAD, the SecoSET and Amplifex-Diene reagents are commonly used to detect 25(OH)VitD and 1α,25(OH)2VitD, respectively. However, they are more challenging for comprehensive profiling of vitamin D metabolites. It is acknowledged that the size and the fixed charge of derivatization reagents dramatically change the chromatography and can lead to poor separation of the derivatized vitamin D metabolites (25). In addition, some vitamin D derivatives will share the same MS product ion (25, 38), which may cause a cross-interference for the poor separating analytes {for example, 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [24R,25(OH)2VitD3] and 1α,25(OH)2VitD3}. PTAD is therefore the common choice for comprehensive quantification of vitamin D metabolites. 2-Nitrosopyridine (PyrNO), a click or Diels-Alder derivatization reagent and an excellent dienophile, offers the enhanced sensitivity of the SecoSET and Amplifex reagents, while retaining the excellent chromatographic properties.

Besides the choice of derivatization reagent, the accurate detection of vitamin D metabolites may be improved by optimizing the sample extraction method to decrease the ion suppression. For example, using immunoextraction proved to be more superior than SPE for purifying 1α,25(OH)2VitD from interfering compounds, where a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for 1α,25(OH)2VitD (3 pg/ml) was dramatically improved after PTAD derivatization (23, 24). However, the immunoextraction method was developed only for 1α,25(OH)2VitD and did not include other metabolites, 25(OH)VitD and 24R,25(OH)2VitD. These metabolites are also important to quantify, because the 24R,25(OH)2VitD has proved to be a critical component for healing processes in tissues and bones, and knowing the levels of both 25(OH)VitD and 24R,25(OH)2VitD is useful for epidemiological studies (35). In addition, immunoextraction required a relatively large sample volume (400–500 µl) compared with other methods. This suggests that a more sensitive and comprehensive method for quantification of major vitamin D metabolites will have value.

For this study, we developed a new method for quantification of vitamin D metabolites using liquid-liquid extraction followed by solid-phase extraction (LLE-SPE) and PyrNO as a derivatization reagent. The method combines both LLE and SPE to reduce the serum ion suppression of dihydroxyvitamin D. Organicnitroso compounds and their rich chemistry have been studied for more than 60 years, and broad applications have been found in organic synthesis, as derivatization reagents for drug discovery and other applications (39–42). To the best of our knowledge, their utility for improving ionization efficiency has not been explored. The PyrNO reagent contains a reactive dienophile and results in better multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) signal intensity than the previously reported PTAD. As a result, the combination of the LLE-SPE and derivatization procedure followed by LC/MS/MS analysis can accurately quantify the major vitamin D metabolites from a small sample volume (100 µl). For example, we quantify1α,25(OH)2VitD; 24R,25(OH)2VitD; and 25(OH)VitD in 100 µl of serum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

The 1α,25(OH)2VitD3, 1α,25(OH)2VitD2, 25(OH)VitD2, and 25(OH)VitD3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The 24R,25(OH)2VitD3 was from BIOMOL (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Deuterated surrogates of vitamin D metabolites, 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD2-d6, were from Medical Isotopes (Pelham, NH), and 25(OH)VitD3-d6 was from Synthetica (Oslo, Norway). Pooled human serum was prepared in our laboratory. The 12-(3-cyclohexyl-ureido)-dodecanoic acid (CUDA) was synthesized in our laboratory. Hexane (mixture of isomers), acetonitrile, methanol, glacial acetic acid, and potassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Deionized water (18.1 MΩ/cm) was prepared in-house and used for mobile phase preparation and SPE. Oasis HLB 1-ml (30 mg of sorbent) SPE cartridges were purchased from Waters Corp. (Milford, MA). PyrNO was synthesized in the laboratory (see supplemental data).

Stock and calibration solutions

Calibration solutions of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD2 were prepared in 4% BSA in PBS buffer at levels of 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 nM. Similarly, calibration solutions of 24R,25(OH)2VitD3, 25(OH)VitD3, and 25(OH)VitD2 were at the levels of 0.2, 0.4, 1, 2, 10, 20, 100, 200, 400, and 1,000 nM. The internal standard solution was prepared in methanol containing 20 nM 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6, 20 nM 1α,25(OH)2VitD2-d6, and 200 nM 25(OH)VitD3-d6. Analysis of 24R,25(OH)2VitD3 and 25(OH)VitD2 relied on 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6 and 25(OH)VitD3-d6 as internal standards for quantification, respectively.

Sample preparation

The stock standard solution (50 µL) or serum/plasma samples (100 µL) were spiked with an internal standard solution (10 µL), mixed, and incubated for 30 min. After that, two LLE and one SPE methods were used in vitamin D extraction. The first LLE method was involved in protein precipitation. The vitamin D metabolites were released from the binding protein with the addition of 600 µl methanol/acetonitrile (80/20), followed by mixing with a Vortex® and centrifugation at 20,000 g (Eppendorf centrifuge 5804R) for 10 min.

The supernatant from protein precipitation was transferred into 2-ml microcentrifuge tubes, followed by the addition of 600 µl of 0.4 M K2HPO4. Then, 600 µl hexane was added for another LLE. The tubes were mixed for 5 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 20,000 g. As a result, all dihydroxy vitamin D metabolites [1α,25(OH)2VitD and 24R,25(OH)2VitD3] remained in the aqueous phase. Therefore, the aqueous layer [1α,25(OH)2VitD and 24R,25(OH)2VitD3] was further processed by SPE as described in supplemental data. The hydroxyvitamin D metabolites [25(OH)VitD] were extracted to the hexane phase. Finally, the hexane layer [25(OH)VitD) was transferred and evaporated on an RC10.22 vacuum concentrator (Jouan, Winchester, VA). The two dried samples, hydroxyvitamin D and dihydroxyvitamin D, were derivatized with PyrNO and analyzed separately.

Derivatization

PyrNO in methanol (2.5 mM, 40 µl) was added, and it redissolved the dried samples. Samples were subsequently transferred into an amber glass vial and were heated in the sand bath at 70°C for 1 h to complete derivatization. These samples were subsequently mixed with CUDA (10 µl, 200 nM), transferred to HPLC vials with 100 µl volume inserts, and stored at −20°C until analysis. Here, CUDA was added to account for instrument variability.

LC/MS/MS analysis

Separation of vitamin D metabolites was performed on an Agilent 1200 SL Liquid Chromatography series (Agilent Corp., Palo Alto, CA). The samples were kept in the autosampler at 4°C, and 10 µl samples were injected on the column. The Eclipse Plus C18 2.1 × 150 mm 1.8 µm column (Agilent) was kept at 50°C. Mobile phase A was water with 0.1% glacial acetic acid. Mobile phase B consisted of acetonitrile with 0.1% glacial acetic acid. Gradient elution was performed at a flow rate of 250 µl/min. Chromatography was optimized to separate all analytes from each other and the chief interferents in 13.0 min. The HPLC gradient is given in supplemental Table S1. The optimized instrument parameters are given in supplemental Table S2. The analytes were quantified by using a 4000 Q-Trap tandem mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems Instrument Corp., Foster City, CA) equipped with an electrospray source (Turbo V), operating in a positive MRM mode. The LC/MS/MS conditions are described in Materials and Methods and supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

Derivatization and extraction method comparison

The improved ionization after PyrNO derivatization was evaluated by comparing MS signals between PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and PTAD-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 in the MRM mode. The sensitivity of the LLE-SPE method was also compared with that from SPE alone. Finally, the PyrNO method was compared with the PTAD method by using the same pooled serum samples.

Method validation: calibration and sensitivity

LLOQ in PBS (Table 1) was the minimum concentration giving a ratio of signal to noise (S/N) > 10 in 4% BSA in PBS buffer. To calculate the LLOQ in serum samples, known concentrations of five vitamin D metabolites were diluted with 4% BSA in PBS buffer and tested by using our analysis protocol.

TABLE 1.

LLOQ and linear ranges of vitamin D metabolites

| Vitamin D Metabolites | Limit of Quantification in BSA [pmol/l (pg/ml)] | LLOQ in human serum [pmol/l (pg/ml)] | Linear Range (nmol/l) |

| 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 | 5.0 (2.1) | 25 (10) | 0.01–50 |

| 1α,25(OH)2VitD2 | 5.0 (2.1) | 25 (10) | 0.01–50 |

| 24R,25(OH)2VitD3 | 20 (8.4) | 25 (10) | 0.2–1,000 |

| 25(OH)VitD3 | 10 (4) | 100 (40) | 0.2–1,000 |

| 25(OH)VitD2 | 10 (4) | 100 (40) | 0.2–1,000 |

Recovery

Analytical recovery was determined by spiking both 10 µl 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6 (20 nM) and 10 µl 25(OH)VitD3-d6 (200 nM) into 100 µl pooled human serum before each step in the extraction method, i.e., protein precipitation (precrash), LLE (preLLE), SPE (preSPE), vacuum dry (predry), and postvacuum dry (postdry). Recoveries were calculated by dividing the peak areas of precrash, preLLE, preSPE, and predry by the peak areas of postdry.

Accuracy and precision

Method accuracy and precision were established by analyzing quality control (QC) samples. The QC samples included spiked samples in BSA prepared in PBS buffer and fortified QC samples, prepared by spiking standard compounds in pooled human serum. For intraday accuracy, four extraction replicates of each sample were analyzed within 24 h to provide percent difference between the measured mean and the expected concentration. For interday accuracy, each sample was tested to show percent difference over 3 days. The coefficient of variation provided the precision.

Matrix effect

Three serum samples with deuterated internal standards spiked at three different concentration levels [1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6/1α,25(OH)2VitD2-d6/25(OH)VitD3-d6: set 1, 5/5/25nM; set 2, 10/10/50nM; and set 3, 20/20/100 nM] were prepared. The potential matrix effect present in human serum was calculated by dividing the response of IS spiked in methanol with the response of internal standards spiked in the pooled human serum (43). The absolute ion suppression caused by matrix was given by 100% minus the obtained value of matrix effect.

Verification of the developed method by Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme samples

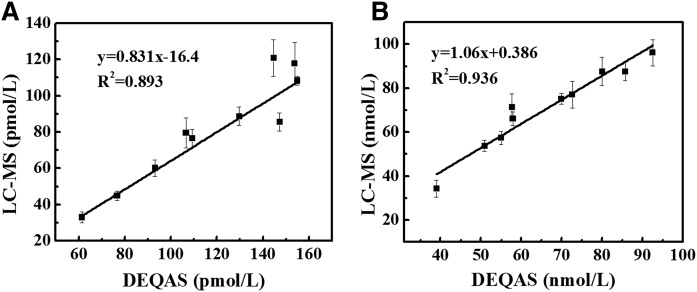

Twenty human serum samples (code nos. 456-465 and 346-355) from the Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme (DEQAS) QC program were selected to test the reliability of our method for analysis of 25(OH)VitD3 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD. All the samples were analyzed by the newly established method in quadruplicate. The known all laboratories trimmed mean (ALTM) values were compared with the resulting values obtained from our method.

RESULTS

Derivatization and LC/MS/MS analysis

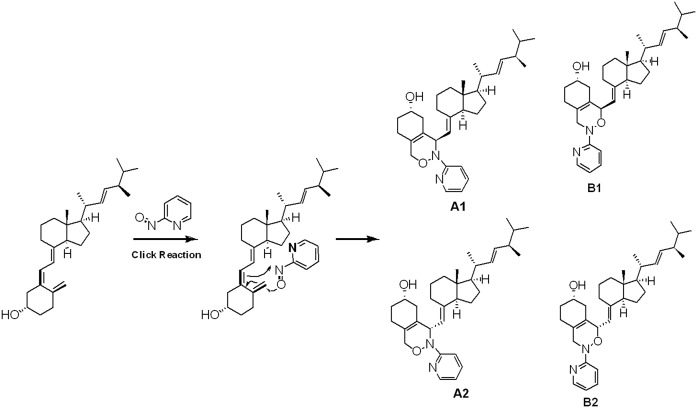

VitD2 was chosen as a representative conjugated diene to first test the click or Diels-Alder reaction with PyrNO. NMR, Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy, and MS were used for product characterization and structure elucidation (see supplemental data). The reaction between PyrNO and VitD2 is illustrated in Fig. 1. The reaction was then optimized for 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 because it was the analyte of the lowest endogenous abundance. Several rounds of optimization were conducted. The best reaction solvent was found to be methanol (supplemental Fig. S1A). This reaction was optimized by using a surrogate solution containing 2.0 nM 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 in methanol and by varying the following conditions: reaction temperature, reaction time, and PyrNO concentration (supplemental Fig. S1B–D). The best yield and consistency were obtained with 2.5 mM PyrNO at 70°C for 1 h. When 1 µM vitamin D metabolites were derivatized by 2.5 mM PyrNO, there were no remnant vitamin D metabolites (limit of detection = 5 nM) that could be detected. The derivatization yield was therefore assumed to be near 100%.

Fig. 1.

Diels-Alder or click reaction between VitD2 and PyrNO. Chemical reactions that are so highly favored that they proceed under a number of conditions are commonly referred to “click” reactions. Click reaction includes a class of biocompatible reactions intended primarily to join substrates of choice with specific biomolecules.

The stability of the derivatized 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 was tested by storing it at −80°C, −20°C, 4°C, and room temperature (RT) over 1 week. Supplemental Fig. S2 shows that, in contrast to 15% loss at 4°C and 20% loss at RT after 1 week when exposed to ambient light, there was no significant analyte loss at −20°C and −80°C. These data on the short-time stability of PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 under various conditions (supplemental Fig. S3) reveal that the main reason behind degradation regardless of temperature is the light exposure. This result is consistent with previous report on light sensitivity of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 (22). Therefore, all derivatized samples were stored below −20°C and less than 1 week before analysis. Derivatization was carried out in the dark.

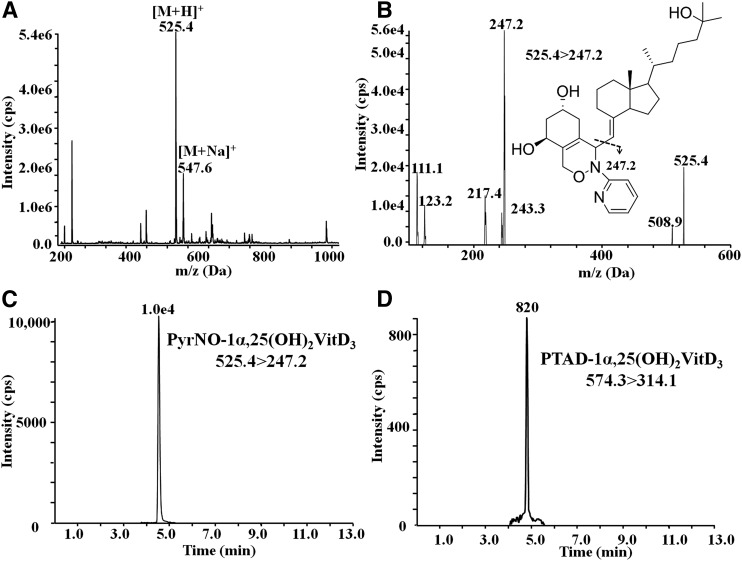

Figure 2A shows the major MS peak at m/z 525.4 and minor MS peak at m/z 547.6, corresponding to [M + H]+ and [M + Na]+ of PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3, respectively, in the direct-infusion full-scan mass spectrum. To avoid formation of sodiated ions, 0.1% glacial acetic acid was added in the HPLC mobile phase. The product ion scan of [M + H]+ (m/z 525.4) (Fig. 2B) shows the major fragment ion at m/z 247.2 with the collision energy at 30 eV, derived from the cleavage of C6-C7 bond in the 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 skeleton. The same fragmentation pattern is also observed for the other vitamin D metabolite derivatives. As a result, the ion transitions in supplemental Table S3 were selected for the quantification of vitamin D metabolites as their PyrNO derivatives. Collision energy (CE), declustering potential (DP), and collision cell exit potential (CXP) were optimized by direct infusion using a syringe pump. Because the DP value is affected not only by the chemical properties, but by the solvent composition and HPLC flow speed, the DP value was further optimized under the optimized HPLC conditions. The optimized MS/MS ion transition, CE, DP, and CXP value are listed in supplemental Table S3.

Fig. 2.

A: Direct infusion full-scan mass spectrum of the PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 product. B: Fragmentation of protonated PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3. C: Comparison of MRM intensity between PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and PTAD-1α,25(OH)2VitD3. The concentration of PTAD and PyrNO were 4.3 and 2.5 mM, respectively. The concentrations of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 for PTAD and PyrNO derivatization are both 1.5 nmol/l.

Chromatography

In theory, a total of four isomers may be produced in the Diels-Alder reaction between PyrNO and VitD. The reaction could produce two regioisomers (A and B in Fig. 1), and each of the regioisomers is composed of two diastereoisomers (A1 and A2; B1 and B2). However, it has been suggested that the overall structure and the nature of the substituent on the unsymmetrical dienes and dienophiles affect the regioselectivity of the Diels-Alder reaction. Leach and Houk (44) recently published an excellent study on the mechanisms of the hetero-Diels-Alder reaction with nitroso species in which they drew generalizations on the regioselectivity in this reaction based on the literature data and quantum mechanical calculations. According to their results, the distal isomer (regioisomer A; Fig. 1) should be favored in the reaction between vitamin D and PyrNO. This suggested regioselectivity was further supported by the model reaction between vitamin D2 and PyrNO. The nuclear Overhauser effect experiments on the isolated major product revealed that it is a single regioisomer comprising two diastereoisomers (A1 and A2) (see NMR data in the supplemental data). The ratio between the two diastereoisomers is approximately 1:4 (supplemental Fig. S4).

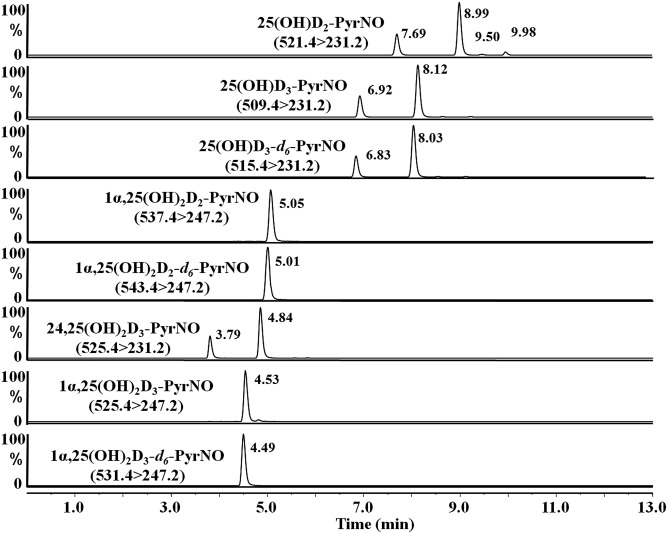

Column temperature, mobile phase composition, and HPLC gradient were optimized to separate all five targeted vitamin D metabolite derivatives, i.e., 25(OH)VitD3, 25(OH)VitD2, 1α,25(OH)2VitD3, 1α,25(OH)2VitD2, and 24R,25(OH)2VitD3. A representative chromatogram of the targeted vitamin D metabolites is illustrated in Fig. 3. The separation of the two diastereoisomers of each vitamin D metabolite depends on the mobile phase and analyte structure. As shown in Fig. 3, diastereoisomers of PyrNO-24R,25(OH)2VitD3, PyrNO-25(OH)VitD3, and PyrNO-25(OH)VitD2 can be separated as twin peaks under the optimized gradient condition (supplemental Table S1). In contrast, only one peak was detected for PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD2 with this gradient system, presented in Fig. 3. Although the separation of two diastereoisomers of PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 can be achieved (supplemental Fig. S5), the separation does not provide any improvement on quantification analysis.

Fig. 3.

Chromatography of PyrNO derivatives of major vitamin D metabolites and two deuterated surrogates of vitamin D metabolites. The separation condition is described in Materials and Methods. The HPLC gradient for separation of vitamin D metabolites is shown in supplemental Table S1.

Advantage of PyrNO compared with PTAD and Amplifex-Diene

Because of the presence of a cis-conjugated diene group in vitamin D and its metabolites, a highly reactive dienophile can be used to enhance electrospray ionization. Traditionally, dienophiles like PTAD were commonly used, followed by detection using LC/MS/MS, leading to 100-fold increases in ion intensity over the underivatized analytes and allowing for a relatively accurate quantification of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 (20, 31). In our previous research, PTAD derivatization after SPE had achieved a LLOQ of 60 pM (25 pg/ml) for the major metabolites using 0.5 ml of serum. However, the sensitivity of the method based on its reported LLOQs is sometimes not adequate to quantify low levels of 1α,25(OH)2VitD accurately, particularly with the small sample volume.

We demonstrate here the use of PyrNO as a highly effective derivatization reagent for LC/MS/MS detection of Vitamin D metabolites. PyrNO is a click or Diels-Alder reaction reagent for derivatizing diene-containing compounds that, as shown here, provides a better ionization efficiency than PTAD. From the available proton affinities of functional groups of PTAD-VitD and PyrNO-VitD in supplemental Table S4, we deduce that the PyrNO-VitD complex is more likely than PTAD-VitD to capture a proton. Additionally, the available pKa value of the conjugated acids of functional groups in PyrNO-vitamin D and PTAD-VitD (supplemental Table S4) also indicate that the PyrNO-VitD complex has a higher proton affinity than PTAD-VitD. These data in Fig. 2 C, D show an approximately 5-fold increase in signal intensity for the PyrNO derivative as compared with the PTAD derivative, each analyzed under their own optimized experimental condition.

The reaction rate of PyrNO was evaluated by comparing PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and PTAD-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 in the MRM mode. Supplemental Fig. S6 shows that PTAD reacts more quickly than PyrNO at 22 and 50°C. Supplemental Fig. S1C shows that PyrNO reacts quickly at 70°C and the reaction is completed in an hour.

The Amplifex-Diene reagent is reported to result in 10-fold ioniziation efficiency improvement over PTAD. However, the Amplifex-Diene reagent results in a large change of the hydrophobicity of the vitamin D complex, and the chromatopraphic retention will be dominated by the contribution of the reagent. As is shown in supplemental Fig. S7A and Fig. 3, when similar chromatographic conditions for the Amplifex-Diene and PyrNO derivatives are used, the permanently charged derivatives elute earlier than PyrNO derivatives. The smaller difference of polarity among the permanently charged derivatives requires more carefully optimization of separation. Even when chromatography is optimized for the more polar Amplifex-Diene derivatives (supplemental Fig. S7B), it is still challenging to obtain baseline resolution of the early eluting peaks with the permanently charged reagent. Therefore, the separation of the Amplifex-Diene-derivatized vitamin D metabolites will be more challenging, especially given that the Amplifex-Diene derivatives of vitamin D will share the same MS product ion (25, 38), potentially causing a cross-interference, especially for 24R,25(OH)2VitD3 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 (supplemental Fig. S7B). This limitation does not detract from the excellent sensitivity of that for the advertised use of the Amplifex-Diene reagent in the quantitative analysis of just 1α,25(OH)2VitD.

The data in supplemental Fig. S8 show that derivatization of vitamin D metabolites with PyrNO is water-tolerant. By comparison of PyrNO derivatization, the complete removal of water before Amplifex-Diene derivatization was found to be critical to obtain a high level of reaction completeness (supplemental Fig. S9).

Newly developed extraction method to reduce the matrix effect (ion suppression)

Another approach to promote the accurate detection of 1α,25(OH)2VitD is by choosing a highly effective sample preparation method to decrease the ion suppression. Previous researchers found significant interfering compounds with retention time similar to 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 (20–23). These interferences were regarded as a derivatization product from the matrix. In this regard, immunoaffinity extraction is among the best techniques for purifying 1α,25(OH)2VitD from interfering compounds (23, 24). However, 25(OH)VitD and 24R,25(OH)2VitD will be lost during the sample preparation process. A growing number of publications illustrate that knowing the levels of both hydroxyvitamin D and dihydroxyvitamin D are important. Although SPE preparation is a more comprehensive extraction method that can extract all major vitamin D metabolites, and proved to cause lower ion suppression than LLE preparation, there are still interfering peaks with similar retention times to 1α,25(OH)2VitD3, thereby impairing the sensitivity-improving effects of derivatization (20).

Here, we described a new sample preparation technique to extract all these major vitamin D metabolites, consisting of protein precipitation to release the vitamin D metabolites from serum protein and LLE-SPE to decrease the ion suppression. The extraction solution after protein precipitation was composed of methanol/acetonitrile/water (4:1:5.8). Hexane was the extraction solvent, and it was immiscible with methanol/acetonitrile/water. The combination of the hexane extraction and SPE will benefit in increasing the sensitivity by eliminating the most matrix effect. This partition takes advantage of the fact that hexane and methanol/acetonitrile are not miscible, and quite similar compounds can be partitioned between them by altering the amount of water in the methanol/acetonitrile layer.

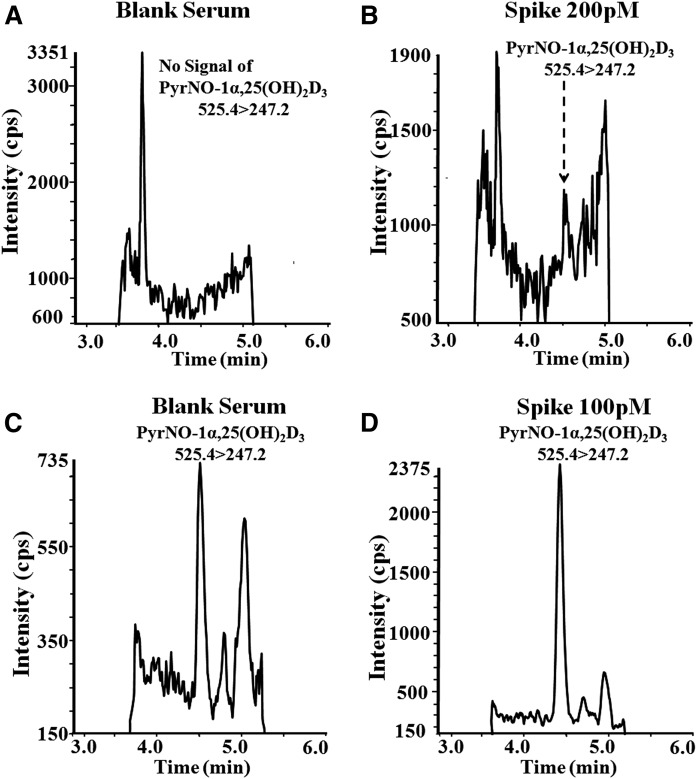

During hexane extraction, hydroxy-vitamin D [25(OH)VitD3 and 25(OH)VitD2] were extracted into the hexane layer, whereas dihydroxy-vitamin D [i.e., 1α,25(OH)2VitD3, 1α,25(OH)2VitD2 and 24R,25(OH)2VitD3] remained in the methanol/acetonitrile/water layer after LLE. The hypophase was further processed by SPE before PyrNO derivatization. Fig. 4 shows the comparison of the samples processed by using SPE and LLE-SPE. The introduction of the LLE step in the sample preparation procedure proved to be beneficial for decreasing the ion suppression because the baseline noise resulting from LLE-SPE was significantly lower than that resulting from the SPE samples, at 200 and 600 counts, respectively. After the LLE-SPE procedure, matrix interferences associated with PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 were reduced in both blank (Fig. 4C) and spiked (Fig. 4D) pooled human serum. After SPE alone, no signal for PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 was observed until the spiked concentration reached 200 pM (Fig. 4A, B). Thus, it is evident that LLE-SPE is better at purifying 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 than SPE alone, because it can reduce most of the interfering components, including 25(OH)VitD. This LLE-SPE purification procedure can also provide higher S/N values in the PTAD method by comparison with the normal SPE preparation procedure. As shown in supplemental Table S5, either PyrNO- or PTAD-derivatized dihydroxyvitamin D metabolites resulted in better sensitivities after LLE-SPE purification than after SPE alone. It is obvious that preparing samples by using LLE-SPE followed by derivatization with PyrNO can provide the most sensitive approach to do quantitative analysis of all dihydroxyvitamin D metabolites. In the LLE step, hydroxyvitamin D was extracted into the hexane layer along with other interfering compounds that could compete with ionization of dihydroxyvitamin D, which will further help increase the ionization of dihydroxyvitamin D. The remaining dihydroxyvitamin D in the lower layer (methanol/acetonitrile/water layer) was further purified by using SPE. By a comparison of the absolute ion intensity of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6, the LLE-SPE method provided a 2-4-fold increase in the detection sensitivity of dihydroxyvitamin D over the SPE alone. Finally, the LLOQ of the new assay is approximately 10-fold better than that of the PTAD assay (supplemental Table S5).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of LLE-SPE and SPE methods of decreasing the ion suppression. Detection of PyrNO-1α,25(OH)2VitD3 in 100 µl of serum after LLE-SPE and SPE purification. A: SPE purification of pooled human serum. B: SPE purification of spiked human serum. The spiked concentration is 200 pM. C: LLE-SPE purification of pooled human serum. D: LLE-SPE purification of spiked human serum. The spiked concentration is 100 pM.

Linearity, limit of quantification, recovery, accuracy and precision, matrix effect

Method validation results are presented in Table 1. Excellent linearity (R2 > 0.99) was obtained for the 10-point calibration curve over the 0.01–50 nM concentration range for both 1α,25(OH)2VitD2 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and between 0.2 and 1,000 nM for 24R,25(OH)2VitD3, 25(OH)VitD3, and 25(OH)VitD2.

In 100 µl 4% BSA in PBS buffer, the LOQ of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3, 1α,25(OH)2VitD2, 24R,25(OH)2VitD3, 25(OH)VitD3, and 25(OH)VitD2 are determined to be 5 pM (2 pg/ml), 5 pM (2 pg/ml), 20 pM (8 pg/ml), 10 pM (4 pg/ml), and 10 pM (4 pg/ml), respectively. Because of ion suppression in human blood samples, the LLOQ of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD2 was validated as 25 pM (10 pg/ml), in 100 µl human serum (supplemental Fig. S10). This LLOQ was obtained by diluting DEQAS samples with known concentrations of these analytes.

The recoveries of each of the extraction procedures of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6 and 25(OH)VitD3-d6 are listed in supplemental Fig. S11A, B. The recoveries of preLLE and preSPE are similar, indicating no analyte loss during LLE. The analytical recovery (precrash) of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6 and 25(OH)VitD3-d6 were both over 85%.

The intraassay and interassay accuracy of PBS buffer QC samples are greater than 80%, and the precision (relative SD) does not exceed 20%, as shown in Table 2. These data indicate that the developed method has a satisfactory reproducibility. The spiked pooled serum samples show good accuracy that ranges from 2.6% to 16.14% (Table 3). All relative SD values of the spiked pooled serum samples were below 16%.

TABLE 2.

Accuracy and precision of the PyrNO method for quantification of vitamin D metabolites in 4% BSA in PBS buffer

| Vitamin D Metabolites | Spiked Concentration (nmol/l) | Detected Concentration [Mean (SD), nmol/l] | Intraday Accuracy (%) | Intraday Precision (%) | Interday Accuracy (%) | Interday Precision (%) |

| 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 | 0.01 | 0.010 (0.001) | 3.75 | 11.9 | 4.75 | 14.9 |

| 0.1 | 0.086 (0.004) | 14.2 | 4.32 | 14.8 | 13.8 | |

| 1 | 0.863 (0.011) | 13.7 | 1.28 | 14.9 | 2.65 | |

| 10 | 8.16 (0.103) | 18.3 | 1.26 | 14.8 | 4.39 | |

| 1α,25(OH)2VitD2 | 0.01 | 0.009 (0.002) | 8.12 | 18.7 | 11.1 | 17.0 |

| 0.1 | 0.082 (0.002) | 18.0 | 1.68 | 13.8 | 7.86 | |

| 1 | 0.897 (0.011) | 10.3 | 1.20 | 7.85 | 3.67 | |

| 10 | 8.26 (0.119) | 17.4 | 1.44 | 14.3 | 5.69 | |

| 24R,25(OH)2VitD3 | 0.4 | 0.330 (0.007) | 17.6 | 2.00 | 4.25 | 17.4 |

| 4 | 4.01 (0.152) | 0.313 | 3.77 | 10.4 | 12.3 | |

| 40 | 37.1 (0.700) | 7.19 | 1.89 | 0.281 | 8.65 | |

| 25(OH)VitD3 | 2 | 1.77 (0.190) | 11.3 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 9.41 |

| 20 | 21.6 (0.637) | 7.938 | 2.95 | 8.55 | 3.33 | |

| 200 | 195 (2.92) | 2.50 | 1.50 | 1.92 | 1.77 | |

| 25(OH)VitD2 | 2 | 1.83 (0.153) | 9.88 | 8.49 | 7.90 | 8.77 |

| 20 | 21.1 (0.606) | 5.62 | 2.87 | 5.25 | 2.14 | |

| 200 | 199 (5.58) | 0.750 | 2.81 | 0.081 | 3.39 |

PBS buffer was 100 μl.

TABLE 3.

Accuracy and precision of the PyrNO method for quantification of vitamin D metabolites spiked in pooled human serum

| Vitamin D Metabolites | Spiked Concentration (nmol/l) | Detected Concentration [Mean (SD), nmol/l] | Intraday Accuracy (%) | Intraday Precision (%) | Interday Accuracy (%) | Interday Precision (%) |

| 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 | 0.061a (±16.6%) | |||||

| 0.1 | 0.108b (0.009) | 3.32 | 8.44 | 6.40 | 14.7 | |

| 1 | 0.913b (0.044) | 8.71 | 4.80 | 10.0 | 5.51 | |

| 1α,25(OH)2VitD2 | ||||||

| 0.1 | 0.103b (0.016) | 14.0 | 15.3 | 10.3 | 11.9 | |

| 1 | 1.15b (0.040) | 12.7 | 3.48 | 6.19 | 8.88 | |

| 24R,25(OH)2VitD3 | 7.15a (±8.07%) | |||||

| 1 | 1.00b (0.122) | 7.26 | 12.1 | 14.7 | 5.22 | |

| 10 | 10.5b(0.708) | 15.9 | 6.71 | 15.9 | 13.0 | |

| 25(OH)VitD3 | 28.3a (±5.56%) | |||||

| 4 | 3.77b (0.342) | 5.83 | 9.08 | 8.54 | 1.70 | |

| 40 | 33.8b (1.65) | 15.5 | 4.88 | 14.2 | 1.51 | |

| 25(OH)VitD2 | 8.62a (±17.9%) | |||||

| 4 | 3.71b (0.191) | 7.21 | 5.14 | 2.62 | 5.32 | |

| 40 | 33.5b (1.06) | 16.1 | 3.18 | 15.5 | 1.12 |

Pooled human serum was 100 μl.

Concentration of targeted vitamin D metabolites in pooled human serum.

The endogenous level of targeted vitamin D metabolites have been subtracted from the measured value.

A deuterated internal standard presents a similar matrix effect to the targeted analytes and is therefore usually used to normalize the ion suppression caused by matrix (43). Supplemental Table S6 shows that the average of serum matrix effects is more than 68%, depending on different analytes at different levels. The ion suppression of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6, 1α,25(OH)2VitD2-d6, and 25(OH)VitD3-d6 were tested to be between 14.3% and 25.6%, 29.3% and 31.4%, and 12.5% and 22.5%, respectively (supplemental Table S7). It is worth mentioning that deuterium-labeled compounds are commonly subject to chromatographic shifts relative to the targeted analytes, known as the chromatographic isotope effect (45). In this paper, 1α,25(OH)2VitD-d6 and 25(OH)2VitD3-d6 were shifted 0.04 and 0.09 min from 1α,25(OH)2VitD and 25(OH)2VitD3, respectively. This may result in a small impact on the overall method accuracy.

Method comparisons

We validated our method using the reference samples from DEQAS, which was established to ensure the analytical reliability of 25(OH)VitD3 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD. The average mean values of DEQAS samples were calculated from different testing methods, including Cusabio ELISA (Cusabio, College Park, MD), DiaSorin RIA, DIASource RIA (DIASource, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium), IDS RIA (Immunodiagnostic Systems, Tyne and Wear, UK), IDS enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Immunodiagnostic Systems), IDS-Isys (Immunodiagnostic Systems), Immundiagnostik ELISA (Immundiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany), and LC/MS/MS. Twenty random DEQAS samples were analyzed by the developed method in quadruplicate. The new method was verified by using these samples to compare the concentration of vitamin D metabolites obtained by our method with the reported DEQAS data (Fig. 5). Figure 5A shows an excellent linear correlation (R2 = 0.936) of our results with DEQAS data for 25(OH)VitD3. The proportional and constant biases were 1.06 and 0.386, respectively. Figure 5B shows good correlation for 1α,25(OH)2VitD (R2 = 0.893). However, we obtained a proportional bias of 0.831 and constant bias of 16.4 for this analyte. This may simply reflect the methodological differences, because the ALTM is derived predominantly from the immunoassay data. In general terms, the correlation analysis of 25(OH)VitD3 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD provide R2 values of 0.936 and 0.893, respectively, which illustrated the good performance of the new method reported here.

Fig. 5.

A: Comparison of results obtained by the PyrNO method versus DEQAS mean value for analysis of 1α,25(OH)2VitD. B: Comparison of the result obtained by our method versus DEQAS mean value for analysis of 25(OH)VitD3. DEQAS was established to ensure the analytical reliability of 25(OH)VitD3 and 1α,25(OH)2VitD.

DISCUSSION

The quantification of endogenous vitamin D metabolites is critical to further understanding their effects on human health and disease. Most techniques for the previous analysis focused on analysis of 25(OH)VitD, the major circulating form of vitamin D, as a surrogate for the bioactive metabolites. However, the major biologically active form of vitamin D is the 1α,25(OH)2VitD metabolite. The accurate measurement by LC/MS/MS presents a great challenge due to the lack of good ionization and 1,000-fold lower circulating concentrations compared with 25(OH)VitD. Therefore, derivatization to increase the ionization efficiency has been used to increase the sensitivity of LC/MS/MS. PTAD-based methods have been commonly used, followed by detection using LC/MS/MS, leading to 100-fold increases in ion intensity over the underivatized analytes, and they allow for relatively accurate quantification of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 (20, 31). However, the sensitivity of the method based on its reported LLOQs was sometimes not adequate to detect low levels of 1α,25(OH)2VitD. Additionally, there was a strong interference signal around the 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 derivative, reducing accuracy of the method. Larger sample sizes and more extensive cleanup could be helpful, but sample sizes are generally limited in epidemiological studies.

In this paper, we used LLE-SPE and PyrNO to reduce the ion suppression and enhance the ionization efficiency of dihydroxy vitamin D and related metabolites. The strategy has been optimized with emphasis on 1α,25(OH)2VitD3, the targeted analyte having the lowest endogenous abundance. The PyrNO derivatization markedly improved the ionization efficiency of the analytes. A new extraction method combining the LLE and SPE was developed to selectively extract hydroxyvitamin D and dihydroxyvitamin D to different fractions with high recoveries, while minimizing the ion suppression of dihydroxyvitamin D and achieving an ultrahigh sensitivity that enables a comprehensive quantification of all major vitamin D metabolites. Based on the combination of protein precipitation, LLE-SPE, and PyrNO derivatization, this highly sensitive method allows for the robust and comprehensive quantification of the major VitD metabolites by using lower volumes of serum/plasma (100 µl).

For validation, the newly developed method was applied to test the DEQAS samples. Because of the increased sensitivity, both 1α,25(OH)2VitD3 and 25(OH)VitD3 can be accurately quantified in 100-µl serum. As shown in Fig. 5, this method showed a good correlation with the ALTM on DEQAS samples.

Compared with previous methods, the method reported here offers several advantages. The comparisons among PyrNO, PTAD, SecoSET, and Amplifex-Diene derivatization reagents are shown in supplemental Table S8. The sensitivity after PyrNO derivatization improved 10-fold for quantification of 1α,25(OH)2VitD compared with the PTAD derivatization. In this study, PyrNO shows even higher ion intensity of 1α,25(OH)2VitD3-d6 than the corresponding permanently charged derivative (supplemental Fig. S12). Theoretically, the Amplifex-Diene derivatives can provide higher ionization efficiency than PyrNO derivatives. However, as advertised, all Amplifex-Diene derivatives of vitamin D metabolites are eluted out in a very narrow window (<1.0 min; supplemental Fig. S7B). Therefore, the permanent charge on the Amplifex-Diene derivatization reagent offers the advantage of high sensitivity and rapid analysis in separately detecting the 25(OH)VitD and 1α,25(OH)2VitD3. However, the PyrNO reagent offers advantages for more comprehensive profiling of all major vitamin D metabolites on a common C18 reversed column, including 1α,25(OH)2VitD3, 1α,25(OH)2VitD2, 24R,25(OH)2VitD3, 25(OH)VitD3, and 25(OH)VitD2. The immunoextraction method is reported in the literature to be the best extraction method for 1α,25(OH)2VitD, but it only targeted 1α,25(OH)2VitD and excluded important vitamin D metabolites Thus, the method is more comprehensive in that it can detect all the major vitamin D metabolites. It is worth mentioning that the sensitivity of the PyrNO method could be further enhanced by combing it with immunoextraction.

In summary, we developed a new method that allows comprehensive, sensitive, and simultaneous quantitative profiling of all the primary vitamin D metabolites. This method allows the routine measurement of primary vitamin D metabolites in 100-µl aliquots of serum/plasma, including 1α,25(OH)2VitD. The PyrNO method offers a comprehensive and highly sensitive quantification for vitamin D metabolites that may be generally applicable to various diene analytes. Currently, we are also screening other functionalized nitroso compounds to determine whether the ionization efficiency can be further improved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Rand for detailed discussion and revision. We also thank Julia Jones for providing us with the DEQAS samples.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- 1α

- 25(OH)2VitD, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

- 25(OH)VitD

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D

- 1α

- 25(OH)2VitD3-d6: 26,26,26,27,27,27-hexadeuterium-1α,25(OH)2VitD3

- 24R

- 25(OH)2VitD3, 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- 25(OH)VitD3-d6: 26

- 26,26,27,27,27-hexadeuterium-25(OH)VitD3

- ALTM

- all laboratory trimmed mean

- CUDA

- 12-(3-cyclohexyl-ureido)-dodecanoic acid

- DEQAS

- Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme

- LLE-SPE

- liquid-liquid extraction followed by solid-phase extraction

- LLOQ

- lower limit of quantification

- MRM

- multiple reaction monitoring

- PTAD

- 4-phenyl-1,2,4-triazole-3,5-dione

- PyrNO

- 2-nitrosopyridine

- QC

- quality control

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute grant R01 EY021747 (to M.A.W.), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) grant R01 ES002710, NIEHS Superfund Research Program grant P42 ES004699 (to B.D.H.), the West Coast Metabolomics Center at UC Davis (National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant U24 DK097154), and National Institutes of Health/NIEHS grant 1K99ES024806-01 (to K.S.S.L.).

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holick M. F. 2006. Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. J. Clin. Invest. 116: 2062–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeLuca H. F. 2004. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80(Suppl): 1689S–1696S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zerwekh J. E. 2008. Blood biomarkers of vitamin D status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87: 1087S–1091S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knekt P., Kilkkinen A., Rissanen H., Marniemi J., Saaksjarvi K., and Heliovaara M.. 2010. Serum vitamin D and the risk of Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 67: 808–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Checkley W., Robinson C. L., Baumann L. M., Hansel N. N., Romero K. M., Pollard S. L., Wise R. A., Gilman R. H., Mougey E., and Lima J.. 2015. 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels are associated with childhood asthma in a population-based study in Peru. J. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 45: 273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick M. F. 2006. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin. Proc. 81: 353–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annweiler C., Llewellyn D. J., and Beauchet O.. 2013. Low serum vitamin D concentrations in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 33: 659–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter G. D., Jone J. C., and Berry J. L.. 2007. The anomalous behaviour of exogenous 25-hydroxyvitamin D in competitive binding assays. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 103: 480–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsugawa N., Suhara Y., Kamao M., and Okano T.. 2005. Determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in human plasma using high-performance liquid chromatography−tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 77: 3001–3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saenger A. K., Laha T. J., Bremner D. E., and Sadrzadeh S. M.. 2006. Quantification of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 using HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry and examination of reference intervals for diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 125: 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter G. D., Carter R., Jone J. C., and Berry J.. 2004. How accurate are assays for 25-hydroxyvitamin D? Data from the international vitamin D external quality assessment scheme. Clin. Chem. 50: 2195–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollis B. W. 2008. Measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D in a clinical environment: challenges and needs. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 88: 507S–510S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feskanich D., Ma J., Fuchs C. S., Kirkner G. J., Hankinson S. E., Hollis B. W., and Giovannucci E. L.. 2004. Plasma vitamin D metabolites and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 13: 1502–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garland C. F., Garland F. C., Gorham E. D., Lipkin M., Newmark H., Mohr S. B., and Holick M. F.. 2016. The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention. Am. J. Public Health. 96: 252–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill N. T., Zhang J., Leonard M. K., Lee M., Shamma H. N., and Kadakia M.. 2015. 1 alpha, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D-3 and the vitamin D receptor regulates Delta Np63 alpha levels and keratinocyte proliferation. Cell Death Dis. 6: e1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponsonby A. L., McMichael A., and van der Mei I.. 2002. Ultraviolet radiation and autoimmune disease: insights from epidemiological research. Toxicology. 181–182: 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holick M. F. 2005. Vitamin D for health and in chronic kidney disease. Semin. Dial. 18: 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu X., Elizondo R. A., Nielsen R., Christensen E. I., Yang J., Hammock B. D., and Watsky M. A.. 2015. Vitamin D in tear fluid. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56: 5880–5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollis B. W. 1986. Assay of circulating 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D involving a novel single cartridge extract ion and purification procedure. Clin. Chem. 32: 2060–2063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clive D. R., Sudhaker D., Giacherio D., Gupta M., Schreiber M. J., Sackrison J. L., and MacFariane G. D.. 2002. Analytical and clinical validation of a radioimmunoassay for the measurement of 1,25 dihydroxy Vitamin D. Clin. Biochem. 35: 517–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronov P. A., Hall L. M., Dettmer K., Stephensen C. B., and Hammock B. D.. 2008. Metabolic profiling of major vitamin D metabolites using Diels–Alder derivatization and ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 391: 1917–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan X., Weinstock-Guttman B., Wang H., Bang E., Li J., Ramanathan M., and Qu J.. 2010. Ultrasensitive quantification of serum vitamin D metabolites using selective solid-phase extraction coupled to microflow liquid chromatography and isotope-dilution mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 82: 2488–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strathmann F. G., Laha T. J., and Hoofnagle A. N.. 2011. Quantification of 1α,25 dihydroxy vitamin D by immunoextraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 57: 1279–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan C., Kosewick J., He X., Kozak M., and Wang S.. 2011. Sensitive measurement of serum 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry after removing interference with immunoaffinity extraction. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 25: 1241–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedman C. J., Wiebe D. A., Dey S., Plath J., Kemnitz J. W., and Ziegler T. E.. 2014. Development of a sensitive LC/MS/MS method for vitamin D metabolites: 1,25Dihydroxyvitamin D-2&3 measurement using a novel derivatization agent. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 953-954: 62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lensmeyer G. L., Wiebe D. A., Binkley N., and Drezner M. K.. 2006. HPLC method for 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurement: comparison with contemporary assays. Clin. Chem. 52: 1120–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glendenning P., Taranto M., Noble J. M., Musk A. A., Hammond C., Goldswain P. R., Fraser W. D., and Vasikaran S. D.. 2006. Current assays overestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D-3 and underestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D-2 compared with HPLC: need for assay-specific decision limits and metabolite-specific assays. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 43: 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gathungu R. M., Flarakos C. C., Reddy G. S., and Vouros P.. 2013. The role of mass spectrometry in the analysis of vitamin D compounds. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 32: 72–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volmer D. A., Mendes L. R., and Stokes C. S.. 2015. Analysis of vitamin D metabolic markers by mass spectrometry: current techniques, limitations of the “gold standard” method, and anticipated future directions. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 34: 2–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liebisch G., and Matysik S.. 2015. Accurate and reliable quantification of 25-hydroxyvitamin D species by liquid chromatography high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 56: 1234–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seiden-Long I., and Vieth R.. 2007. Evaluation of a 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D enzyme immunoassay. Clin. Chem. 53: 1104–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vreeken R. J., Honing M., vanBaar B. L., Ghijsen R. T., de Jong G. J., and Brinkman U. A.. 1993. On-line post-column Diels-Alder derivatization for the determination of vitamin D3 and its metabolites by liquid chromatography/thermospray mass spectrometry. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 22: 621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogawa S., Ooki S., Morohashi M., Yamagata K., and Higashi T.. 2013. A novel Cookson-type reagent for enhancing sensitivity and specificity in assessment of infant vitamin D status using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 27: 2453–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufmann M., Gallagher J. C., Peacock M., Schlingmann K. P., Konrad M., DeLuca H. F., Sigueiro R., Lopez B., Mourino A., Maestro M., et al. 2014. Clinical utility of simultaneous quantitation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by LC-MS/MS involving derivatization with DMEQ-TAD. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99: 2567–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Netzel B. C., Cradic K. W., Bro E. T., Girtman A. B., Cyr R. C., Singh R. J., and Grebe S. K.. 2011. Increasing liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry throughput by mass tagging: a sample-multiplexed high-throughput assay for 25-hydroxyvitamin D-2 and D-3. Clin. Chem. 57: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J. H., Woenker T., Adamec J., and Regnier F. E.. 2013. Simple, miniaturized blood plasma extraction method. Anal. Chem. 85: 11501–11508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones G., and Kaufmann M.. 2015. Vitamin D metabolite profiling using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 164: 110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan N., and Kaleta E. J.. 2015. Quantitation of 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by LC-MS/MS using solid-phase extraction and fixed-charge derivitization in comparison to immunoextraction. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 53: 1399–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li F., Yang B., Miller M. J., Zajicek J., Noll B. C., Mollmann U., Dahse H. M., and Miller P. A.. 2007. Iminonitroso Diels-Alder reactions for efficient derivatization and functionalization of complex diene-containing natural products. Org. Lett. 9: 2923–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wencewicz T. A., Yang B., Rudloff J. R., Oliver A. G., and Miller M. J.. 2011. N-O chemistry for antibiotics: discovery of N-Alkyl-N-(pyridin-2-yl)hydroxylamine scaffolds as selective antibacterial agents using nitroso Diels-Alder and ene chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 54: 6843–6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carosso S., and Miller M. J.. 2014. Nitroso Diels-Alder (NDA) reaction as an efficient tool for the functionalization of diene-containing natural products. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12: 7445–7468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang B., Miller P. A., Mollmann U., and Miller M. J.. 2009. Syntheses and biological activity studies of novel sterol analogs from nitroso Diels-Alder reactions of ergosterol. Org. Lett. 11: 2828–2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matuszewski B. K., Constanzer M. L., and Chavez-Eng C. M.. 2003. Strategies for the assessment of matrix effect in quantitative bioanalytical methods based on HPLC-MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 75: 3019–3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leach A. G., and Houk K. N.. 2001. Transition states and mechanisms of the hetero-Diels-Alder reactions of hyponitrous acid, nitrosoalkanes, nitrosoarenes, and nitrosocarbonyl compounds. J. Org. Chem. 66: 5192–5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hewavitharana A. K. 2011. Matrix matching in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with stable isotope labelled internal standards-Is it necessary? J. Chromatogr. A. 1218: 359–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.