Abstract

INTRODUCTION

It is standard practice in the UK that if conservative measures or chemical cautery fail to control epistaxis, patients receive nasal packing which is often uncomfortable, requires admission and has well documented associated morbidity. Our study aims to evaluate the use of FloSeal haemostatic sealant in managing patients with epistaxis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients were identified from those referred with active epistaxis. A successful outcome was defined as complete haemostasis with FloSeal alone, with no further significant bleeding requiring admission or further interventions in the subsequent 7 days. Patients reported satisfaction using a ten-point visual analogue scale. Ear, nose and throat doctors recorded patient demographics, time to prepare FloSeal, length of stay, need for further treatment and adverse events on an electronic database.

RESULTS

30 patients were enrolled in the study. The mean time to prepare FloSeal was 5 minutes. The success rate of FloSeal was 90%. The mean length of stay was 2.75 hours. The mean patient satisfaction with FloSeal was 8.4/10. No adverse events occurred.

DISCUSSION

FloSeal was found to be effective in controlling anterior epistaxis. There was a single case of posterior epistaxis which required operative management. The literature largely supports FloSeal in anterior epistaxis, but indicates sphenopalatine artery ligation as the definitive management of posterior epistaxis.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data support the use of FloSeal in patients with anterior epistaxis not controlled with conservative measures or chemical cautery. It was found to be easy to use, is well tolerated by patients and is efficient in financial terms.

Keywords: Floseal matrix, Epistaxis, Clinical study, Review

Introduction

Epistaxis is one of the most common otorhinolaryngology emergencies. The lifetime risk of developing epistaxis is estimated at 60% but, as most cases are self-limiting, only 6% of patients with nosebleeds seek medical attention.1 Epistaxis has a bimodal age distribution, with most cases occurring before 10 years and between 45 and 65 years of age.2 According to Hospital Episodes Statistics data for NHS England, in 2009/10 over 2,700 patients had epistaxis controlled in emergency departments. In the same year, there were over 21,000 emergency admissions for epistaxis with a mean 1.9-day inpatient stay. In 2014/15, around 6,400 cases of epistaxis were controlled in emergency departments. Although the number of admissions with epistaxis in 2014/15 was not reported, one can spot the trend in presentations with epistaxis, which is in accordance with projected trends in population ageing and population growth.3,4

It is standard practice in the UK that, if conservative measures or chemical cautery fail to control epistaxis, patients receive nasal packing in the form of Rapid Rhino® (Smith & Nephew, Austin TX, USA), Merocel® (Medtronic, Inc., Fridley, MN, USA) or bismuth iodoform paraffin paste-coated ribbon gauze. Nasal packing is often uncomfortable for the patient, requires admission for observation at significant financial cost and has well documented associated morbidity. FloSeal® (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) is a biodegradable matrix haemostatic sealant composed of gelatin granules and human thrombin. It is applied to a bleeding site topically as a high-viscosity gel. Initial research showed promising results in controlling bleeding in cardiac, vascular and spinal surgery.5 A number of ear, nose and throat (ENT) departments have conducted studies to assess the use of FloSeal in managing cases of epistaxis and the results have been encouraging.6,7,8

This prospective pilot clinical study aims to evaluate the use of FloSeal in managing patients with epistaxis as an alternative to standard nasal packing, in terms of both efficacy and safety, as well as ease of use and patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Patients were identified from those referred with active epistaxis not controlled with conservative measures or chemical cautery to our ENT department at a district general hospital. Referral units included local general practice surgeries and minor injury units, as well as our local emergency department and the emergency department of nearby hospitals without capacity to admit acute ENT patients. Patients with a history of hypersensitivity to materials of bovine origin and those on warfarin with an international normalised ratio (INR) above their therapeutic range were excluded from the study. Consecutive patients were included subject to FloSeal availability. As FloSeal has been an established treatment for epistaxis, its use was approved locally by the department’s clinical director and the trust’s procurement control committee. Since this treatment became standard for all suitable patients in our hospital, ethical approval was not required. Informed verbal consent for the application of FloSeal and inclusion in the study was obtained from all patients.

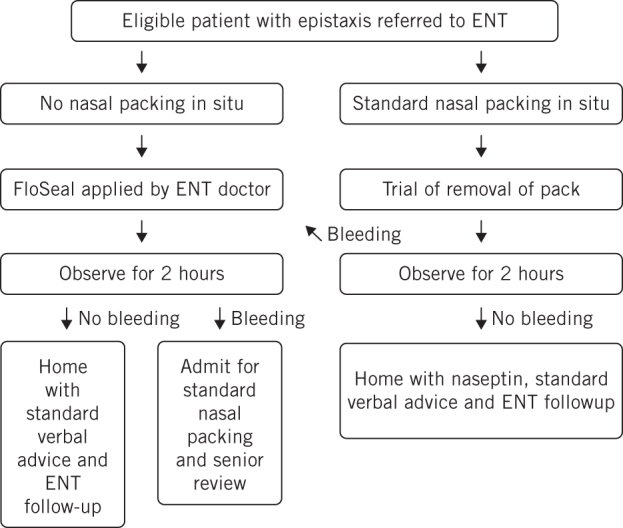

FloSeal was applied by junior ENT doctors, including a foundation trainee year 2, a general practice trainee year 2 , a core surgical trainee year 1, a core surgical trainee year 2 and 2 junior clinical fellows. All doctors received formal supervised training in the application of FloSeal by a local Baxter representative prior to their participation in the study. The on-call doctor would review the patient, suction blood and clots from the patient’s nasal cavity and reconstitute and apply FloSeal as per pack instructions. When the bleeding source was not readily seen, flexible fibreoptic nasendoscopy was performed to identify the level of bleeding and one unit of FloSeal was applied using the appropriate applicator directly to the bleeding point. The remaining gel was used to fill the ipsilateral nasal cavity. Although a rigid nasal endoscope would be more appropriate in this situation, this equipment was not easily available to junior doctors treating patients in the emergency department. Co-phenylcaine was also used as required, owing to its anaesthetic and vasoconstriction properties. When a nasal pack was already in place at the time of review and the patient was eligible and willing to participate in our study, the pack was removed and FloSeal was applied if bleeding occurred during an observation period of 2 hours. No antibiotic prophylaxis was administered. The patient was reassessed 10 minutes later and if there was ongoing epistaxis, the gel and clots were suctioned and a Rapid Rhino® pack was inserted. The first ten patients included in the study were admitted for observation overnight to ensure patient safety. Subsequent patients were discharged home following 2 hours observation and no further bleeding, with standard epistaxis verbal advice and a follow-up appointment one week later in our ENT acute clinic for review. Figure 1 demonstrates a summary of our study protocol.

Figure 1.

Study protocol

A successful outcome was defined as complete haemostasis with FloSeal alone, with no further significant bleeding requiring admission or further interventions in the subsequent 7 days. Patients completed a questionnaire following FloSeal application. Using a ten-point visual analogue scale, patients were asked to rank satisfaction with the technique (1 = extremely dissatisfied, 10 = extremely satisfied). ENT doctors also recorded patient demographics, time to prepare FloSeal, duration of admission, need for further treatment and adverse events for all patients on an electronic database.

Results

All eligible patients approached for enrolment agreed to participate; 30 patients were enrolled in the study from December 2014 to September 2015. The mean patient age was 62 years (range 13 to 98 years); 50% of patients were male and one was a pregnant woman. Seven patients were referred with standard nasal packing in situ. Following removal of packing, during a 2-hour period of observation, all of these patients continued to bleed and FloSeal was applied.

The mean time to prepare FloSeal was 5 minutes. The success rate of FloSeal was 90% (27/30 patients). The three patients for whom FloSeal failed to achieve haemostasis were packed with Rapid Rhino®, which was removed 24 hours later, and one of these patients eventually required sphenopalatine artery ligation. This was the only case of posterior epistaxis in our study. The initial ten patients enrolled were observed in hospital for 24 hours following FloSeal application. For the remaining patients, the mean length of stay was 2.75 hours (range 2–4 hours). One patient was an inpatient under the medical team and remained in the hospital for other reasons, and hence has been excluded from this calculation. All the patients included in the study (n = 30) completed the satisfaction questionnaire. As mentioned, this was a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied). The mean score was 8.4 (range 7–10). We had excellent feedback from patients who had experienced insertion of a nasal pack in the past. One patient said that the process of application of FloSeal was ‘so much better and less painful’. No adverse events occurred with the study patients associated with the use of FloSeal.

Discussion

Our data suggest that FloSeal achieves complete haemostasis with no significant further bleeding requiring admission or other intervention in the subsequent 7 days, in 90% of patients with epistaxis not controlled with conservative measures or chemical cautery. FloSeal was effective without complication in controlling epistaxis, including in one child and one pregnant woman in our study. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relating to the role of Baxter in our study.

A literature review searched PubMed using the terms ‘epistaxis’ and ‘FloSeal’. The titles and abstracts of articles available in English were screened and the full text of potentially relevant articles obtained and reviewed.

Mathiasen and Cruz conducted a prospective, randomised, controlled, non-blinded, crossover clinical trial of FloSeal compared with standard nasal packing in 70 patients with acute anterior epistaxis. FloSeal was judged by physicians to be more effective than nasal packing at initial control of haemostasis (9.9/10 vs. 7.7/10, P < 0.001) and easier to use (9.4/10 vs. 3.2/10, P < 0.001). Patients experienced less discomfort with FloSeal than with nasal packing at initial control (1.4/10 vs. 8.9/10, P < 0.001) and patients using FloSeal were more satisfied overall (9.1/10 vs. 2.9/10, P < 0.001). Fewer ENT consultations were requested for patients using FloSeal (8.6% vs. 31.0%, P < 0.05) and they experienced lower rebleeding rates within 7 days (14% vs. 40%, P < 0.05).6

Côté et al reported a prospective clinical trial conducted on epistaxis patients whose nasal haemorrhage persisted despite adequate nasal packing.7 Although a small sample size (n = 10), they reported success rates with FloSeal of 80% in patients with persistent epistaxis who would have otherwise been taken to the operating theatre.7

Khan et al reported a comparison of outcomes of a series of 101 patients with epistaxis either treated with FloSeal or traditional epistaxis management techniques.8 The reported overall success rate for FloSeal was 14%; successful in 66% of anterior epistaxis cases and in only 9% of posterior epistaxis cases.8 This study supports our finding that FloSeal is less effective in controlling posterior epistaxis. Posterior epistaxis is generally more difficult to control, with a higher failure rate in nasal packing in terms of bleeding control. Endoscopic ligation of the sphenopalatine artery is now emerging as the most effective and cost efficient definitive treatment for this condition.9 There is also research supporting the domiciliary use of use of FloSeal in patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia to prevent admission,10 as well as during and after sinus surgery.11,12

There were no complications associated with the use of FloSeal in our study. This treatment offers a significant benefit over standard nasal packing, which has well documented complications in the literature, including pain and discomfort, alar or columellar skin pressure necrosis, nasal mucosal atrophy, toxic shock syndrome, sinus infection, displacement with airway obstruction, sleep apnoea and cardiovascular collapse secondary to nasal-pulmonary reflex.13 Standard nasal packing also requires admission or follow-up for removal, which is often poorly tolerated by patients.

Our study shows that FloSeal can be prepared quickly at the bedside, with a mean preparation time of 5 minutes. Our data also suggest high patient satisfaction (VAS 8.4) and other studies confirm that it is well tolerated compared with standard nasal packing.6,7

Patients receiving standard nasal packing are usually admitted under ENT for observation in UK hospitals. This is associated with significant financial costs, with an average bed day costing £299 in our hospital. FloSeal costs £106 per unit and so would result in significant financial savings. Furthermore, a hospital admission may have financial implications to the patient, particularly if they are self-employed. At a time of frequent bed crises and cancellations of elective surgery due to a lack of beds, this reduction in inpatient stay is welcomed.

Conclusion

The data from our pilot study support the use of FloSeal in patients with anterior epistaxis not controlled with conservative measures or chemical cautery. It was found to be easy to use, well tolerated by patients and efficient in financial terms. Further prospective, randomised controlled trials are needed to assess the outcomes of the use of FloSeal in comparison to other conventional treatments in controlling epistaxis.

References

- 1.Viehweg TL, Roberson JB, Hudson JW. Epistaxis: diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006; : 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pallin DJ, Chng YM, McKay MP, et al. Epidemiology of epistaxis in US emergency departments, 1992 to 2001. Ann Emerg Med 2005; : 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spielmann PM, Barnes ML, White PS. Controversies in the specialist management of adult epistaxis: an evidence-based review. Clin Otolaryngol 2012; : 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hospital Episode Statistics. Health and Social Care Information Centre. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes (cited July 2016).

- 5.Oz MC, Rondinone JF, Shargill NS. Floseal Matrix: new generation topical hemostatic sealant. J Card Surg 2003; : 486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathiasen RA, Cruz RM. Prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial of a novel matrix hemostatic sealant in patients with acute anterior epistaxis. Laryngoscope 2005; : 899–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Côté D, Barber B, Diamond C et al. FloSeal haemostatic matrix in persistent epistaxis: prospective clinical trial. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; : 304–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan MK, Reda El Bedaway et al. The utility of FloSeal haemostatic agent in the management of epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol 2015; : 353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas R, Wormald P. Update on epistaxis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head NeckSurg 2007; : 180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warner L, Halliday J, James K et al. Domiciliary FloSeal prevents admission for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope 2014; : 2,238–2,240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beyea JA, Rotenberg BW. Comparison of purified plant polysaccharide (HemoStase) versus gelatin-thrombin matrix (FloSeal) in controlling bleeding during sinus surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2011; : 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandra RK, Conley DB, Kern RC. The effect of FloSeal on mucosal healing after endoscopic sinus surgery: a comparison with thrombin-soaked gelatin foam. Am J Rhinol 2003; : 51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soyka M, Nikolaou G, Rufibach K et al. On the effectiveness of treatment options in epistaxis: an analysis of 678 interventions. Rhinology 2011; : 474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]