Abstract

We present a review evaluating all litigation claims relating to hip fractures made in a 10-year period between 2005 and 2015. Data was obtained from the NHS Litigation Authority through a freedom of information request. All claims relating to hip fractures were reviewed. During the period analysed, 216 claims were made, of which 148 were successful (69%). The total cost of settling these claims was in excess of £5 million. The introduction of a best-practice tariff by the Department of Health in 2010 was designed to improve the quality of care for hip fracture patients. This was followed by guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in 2011 and the British Orthopaedic Association in 2012. We analysed claims submitted before and after these guidelines were introduced and no significant difference in the number of claims was noted. The most common cause for litigation was a delay in diagnosis, which accounted for 86 claims in total (40%). Despite the presence of these guidelines and targets, there has not been a significant reduction in the number of claims or an improvement in diagnostic accuracy. This may be due to an increasing level of litigation in the UK but we must also question whether we are indeed providing best-practice care to our hip fracture patients and whether these guidelines need further review.

Keywords: Hip, Fracture, Neck of femur, Negligence, Litigation, Diagnosis

Introduction

The National Health Service Litigation Agency (NHSLA) was established in the UK in 1995 as a not-for-profit special health authority to provide indemnity cover for all medical negligence claims against the NHS. By sharing information regarding previous claims, the organisation is also involved in trying to reduce risk to patients and healthcare staff. Since 2002, the NHSLA has held data for all claims made against the NHS.1 Litigation claims against the NHS have increased year on year and, as a result, there is a growing interest in understanding the aetiology of medical negligence and how to minimise risk.

Surgical specialties are associated with the highest number of claims to the NHSLA,2 with an estimated potential liability up to March 2014 in the region of £26 billion.3 Trauma and orthopaedic surgery generates considerable litigation with the Medical Defence Union (MDU) estimating an average settlement figure of £60,000 per case, based on their own records.4 Claims relating to hip and knee surgery accounted for 20% and 26% of all claims, respectively, with claims relating to delayed diagnosis, wrong site surgery, retained items and other complications associated with surgery.

Hip fractures are an increasing public health issue owing to our ageing population. The average age is 80 years old with an annual incidence of approximately 70,000 in the UK.5 This is expected to rise to over 100,000 by 2020 and, currently, the combined medical and social expenditure is estimated at £2 billion per year. This represents a significant financial burden on the NHS and has led to significant improvements in care over the last 5 years. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidance in 2011 covering the management of hip fractures from admission through to secondary care, designed to reduce the risk of medical negligence and to ensure optimal care.6 This was based on the introduction of a best practice tariff (BPT) for hip fractures in 2010. The BPT was developed to encourage best practice through prompt surgery and appropriate involvement of geriatric medicine.7 Eight key clinical targets are monitored through the National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) and the achievement of these results in the payment of a financial incentive on top of the base tariff. Despite the introduction of these targets and guidelines, the cost of treatment and the rate of complications remain high.

We present data on hip fracture claims over a 10-year period, covering the introduction of NICE/BPT guidelines, and analyse the effect that these have had on both the number and financial cost of these claims.

Methods

Data on all claims made between 2005 and 2015 was requested from the NHSLA under the Freedom of Information Act, 2000. The information supplied included the year of the alleged incident, the status of the claim, details regarding the incident, whether or not the claim was successful and details of any costs incurred (damages, defence costs and claimant costs). Data for claims after 2010 was less detailed, owing to restrictions by the NHSLA on the level of data provided. Two groups were formed to differentiate claims before and after the introduction of NICE/BPT guidelines. Group A represent claims before the guidelines were introduced (2005–2010) and Group B represents claims after the introduction of these guidelines (2011–2015).

Claims was filtered using the keywords ‘hip’, ‘femur’ and ‘fracture’. Claims were then reviewed independently by two reviewers. Only claims relating directly to hip fracture patients were included in our analysis. Claims relating to hip arthroplasty, femoral fractures or other ambiguous claims were excluded. All claims were assessed and categorised into one of four categories: preoperative errors, intraoperative errors, postoperative errors and errors in perioperative management. The event codes used to categorise these claims are listed in Table 1. Descriptive statistics were generated in SPSS® Statistics v22.0 (IBM®).

Table 1.

Categories of claims

| Category | Claim |

|---|---|

| Preoperative | Delay in diagnosis Delay in treatment Inpatient fall leading to fracture |

| Intraoperative | Surgeon error or poor surgical technique Inappropriate choice of operation |

| Postoperative | Death attributed to medical error or inappropriate care Inadequate postoperative care leading to morbidity Inpatient fall leading to injury Infection of wound attributed to surgeon error |

| Perioperative | Death due to medical error or inadequate care Inadequate care leading to pressure sores |

Results

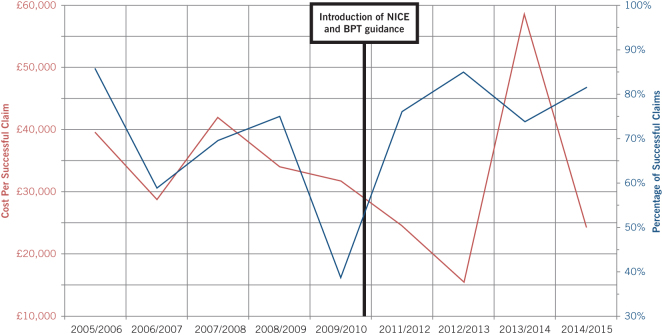

A total of 216 claims relating to hip fractures were analysed over the 10-year period, with a total cost in excess of £5 million (Table 2). The number of successful claims was 148 (68.5%) with an average settlement of £34,378 per claim. Looking at each year individually, there was no significant trend in the percentage of successful claims or the average cost per successful claim (Fig 1).

Table 2.

Breakdown of claims

| Year | Total(n) | Successful | Cost | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | Total | Average/successful | ||

| 2005–2006 | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 237,251.68 | 39,541.95 |

| 2006–2007 | 17 | 10 | 58.8 | 286,690.29 | 28,669.03 |

| 2007–2008 | 23 | 16 | 69.6 | 671,814.16 | 41,988.39 |

| 2008–2009 | 20 | 15 | 75.0 | 509,726.70 | 33,981.78 |

| 2009–2010 | 39 | 15 | 38.5 | 475,802.96 | 31,720.20 |

| 2011–2012 | 25 | 19 | 76.0 | 468,311.80 | 24,647.99 |

| 2012–2013 | 20 | 17 | 85.0 | 262,998.37 | 15,470.49 |

| 2013–2014 | 38 | 28 | 73.7 | 1,637,226.11 | 58,472.36 |

| 2014–2015 | 27 | 22 | 81.5 | 538,166.12 | 24,462.10 |

Figure 1.

Percentage and cost of successful claims by year

Before the introduction of NICE/BPT guidelines (Group A) there were 106 claims, of which 62 were successful, resulting in financial compensation totalling £2,181,285 (average of £35,182 per claim). After the introduction of NICE/BPT guidelines (Group B), there was a total of 110 claims, of which 86 were successful, resulting in compensation totalling £2,906,702 (average of £33,799 per claim). The number of claims was similar between both groups and did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.38). The percentage of successful claims was higher in the latter group (78.2% compared with 58.5%) and this was significant (P < 0.02).

The most common reason for litigation claims in both groups was a delay in initial diagnosis and these accounted for 46.2% of claims in Group A and 33.6% of claims in Group B. In Group A, the second highest number of claims was related to inpatient falls leading to hip fractures, accounting for 19.8% of claims. This was not the case in Group B, where no claims relating to inpatient falls were registered.

The second highest number of claims in Group B related to delays in treatment (20%) and failure to perform or interpret x-rays (17.2%). Claims relating to medical errors or inadequate care increased from 10.3% in Group A to 16.4% in Group B. Claims relating to poor surgical decision making reduced from 14.2% in Group A to 9.1% in Group B. The full breakdown of the number of claims by category is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Number of claims by category

Discussion

Claims against orthopaedic surgeons are increasing. In part, this is likely due to the sheer volume of surgeries performed with orthopaedic surgery making up approximately 25% of all surgical interventions performed in the NHS.8 Several articles have looked at NHSLA data for subspecialty areas of orthopaedic surgery, such as hand and wrist fractures and foot and ankle surgery, but no review to date has looked at patients with hip fractures.9,10 These patients form a vulnerable and medically complex group who are especially prone to complications because of their compromised physiology. Our review demonstrates a significant number of claims relating to hip fractures, which carry an associated financial burden. We would suggest that many of these claims are potentially avoidable with adequate medical, surgical and nursing care. Despite the introduction of NICE guidelines, the BPT and other hip fracture treatment standards, we have not observed a significant reduction in the number of claims reported to the NHSLA as one might have expected.

Interestingly the most common category of claims related to delayed diagnosis and this has not significantly reduced between the two groups. We know that approximately 15% of hip fractures are undisplaced and in these cases, clinical examination can be relatively normal and can even include the ability to bear weight.11 In many cases, the clinical history is difficult to elicit. Radiographic changes can be minimal and can appear normal in 1% of cases. Delay in treatment is associated with an increased morbidity and mortality in this frail population group.12 One of the key aspects of the NICE guidelines is to reduce the delay in diagnosis and treatment by developing a pathway to advanced imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT), with the former being the gold standard. If an MRI scan is not available within 24 hours then CT should be used to prevent delay in diagnosis.6 Despite the presence of a clear national guideline, we still seem to be seeing a similar level of diagnostic inaccuracy and delay. We are aware that in some institutions the availability of urgent MRI scans is limited and the scanner is rarely available out of hours. There should, however, be 24-hour access to CT in all institutions within the required timeframe.

There should be some concern over the continued delay in diagnosing hip fractures despite these guidelines, the related financial cost of these claims and, most importantly, the associated morbidity of delaying treatment. We would therefore advocate that, in all patients with a relevant clinical history, we must maintain a high level of clinical suspicion. Where plain radiographs are equivocal and MRI facilities are not available, CT should be performed urgently. We would also advise early liaison with the orthopaedic department regarding equivocal cases. Most institutions use a hip fracture pro forma to ensure optimal care and the acquisition of BPT targets, and we would suggest the inclusion of a diagnostic imaging pathway or checklist on this to ensure that scans are requested where appropriate and any equivocal cases are referred to the orthopaedic department for further reassessment.

Claims related to hip fractures caused by inpatient falls have reduced from almost 20% to zero, which does demonstrate an improvement in patient care, most likely attributable to these guidelines and targets. This is an area that has been highlighted by the BOA and by the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), with the NPSA reporting that approximately 282,000 inpatient falls occur each year. These falls result in significant morbidity and mortality, including around 840 hip fractures, 550 other fractures and 30 intracranial bleeds.13 These cases do not represent true surgical negligence claims and are therefore not the focus of this review. They do, however, represent a significant financial cost to the NHS which appears to have been reduced, based on this review.

There can be no doubt that the introduction of these guidelines and targets have increased the awareness of hip fracture treatment and raised the standard of care. Medical and nursing care has improved and healthcare professionals are more aware of the complex needs of these patients. Despite this, our review of the NHSLA data does demonstrates a persistent number of litigation claims relating to delayed diagnosis, inadequate medical or nursing care, failure to perform or interpret x-rays and intraoperative errors. We would expect that these claims would have reduced in recent years, but this is not the case. The reasons behind this are not clear. Perhaps we still have more work to do in terms of improving patient care or perhaps the number of claims simply represents our increasingly litigious society. Most orthopaedic surgeons will face at least one clinical negligence claim in their professional career.14 There is clearly a need to further develop our knowledge and understanding in this field, as well as improving our diagnostic pathways. Resources within the NHS, such as the NHSLA and the National Learning and Reporting System, offer a platform from which further quantitative and qualitative research can define and explain the reasons for continuing negligence or medical error despite the implementation of evidence-based guidelines.

The main limitation of this review is that the data provided by the NHSLA can be quite restrictive in content. Data, particularly for more recent claims, does not provide specifics on each claim and we are thus unable to analyse each claim in detail to look for further links or confounding factors. Despite this fact, it is hard to ignore the persistent numbers of claims and the significance of delayed diagnosis in hip fracture negligence cases. Further evaluation of the data is needed to understand the precise reasons behind these claims.

References

- 1.NHS Litigation Authority. Factsheet 1: Basic Information 2014–15 http://www.nhsla.com/currentactivity/Documents/NHS%20LA%20Factsheet%201%20-%20basic%20information%202014-15.pdf [date last accessed 14th February 2016].

- 2.NHS Litigation Authority. Factsheet 3: Information on Claims 2014–15 http://www.nhsla.com/currentactivity/Documents/NHS%20LA%20Factsheet%203%20-%20claims%20information%202014-15.pdf [date last accessed 14th February 2016].

- 3.NHS Litigation Authority. Factsheet 2: Financial Information 2014–15 http://www.nhsla.com/currentactivity/Documents/NHS%20LA%20Factsheet%202%20-%20financial%20information%20-%202014-15.pdf [date last accessed 14th February 2016].

- 4.Bones of contention – claims in orthopaedic surgery. MDU Journal. June 2011; . [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Choices website: Hip fracture. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hip-fracture/Pages/introduction.aspx [date last accessed 14th February 2016]

- 6.NICE. CG124 - Hip fracture: The management of hip fracture in adults London: NICE; 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124 [date last accessed 14th February 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monitor. National tariff payment system 2014/15 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-tariff-payment-system-2014-to-2015 [date last accessed 14th February 2016]

- 8.Briggs TWR. Getting It Right First Time. http://www.timbriggs-gettingitrightfirsttime.com. [date last accessed 14th February 2016]

- 9.Ring J, Talbot C, Price J, Dunkow P. Wrist and scaphoid fractures: A 17-year review of NHSLA litigation data. Injury. 2015; : 682–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ring J, Talbot CL, Clough TM. Clinical negligence in foot and ankle surgery: A 17-year review of claims to the NHS Litigation Authority. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2014; : 1,510w4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.No authors listed The care of patients with fragility fracture British Orthopaedic Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariconda M, Costa GG, Cerbasi S, Recano P, Aitanti E, Gambacorta M et al. The determinants of mortality and morbidity during the year following fracture of the hip: a prospective study. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2015; : 383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tingle J. Essential care after an inpatient fall: National Patient Safety Agency advice. British Journal of Nursing. 2011; : 424–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machin JT, Briggs TWR. Litigation in trauma and orthopaedic surgery. Journal of Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2014; :32–8. [Google Scholar]