Abstract

Paragangliomas are rare lung tumours; endobronchial localisation is even more rare. This report describes the case of a 59-year-old patient with a symptomatic endobronchial paraganglioma successfully resected by means of pulmonary lobectomy. Recognition of this uncommon tumour can lead to a correct diagnosis and therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: Paraganglioma, Endobronchial tumour, Surgery

Introduction

Extra-adrenal paragangliomas are rare tumours arising from parasympathetic ganglia, which can present almost throughout the whole body.1 In the literature, less than 30 cases of pulmonary presentation have so far been documented2 and endobronchial localisation is even more rare. We present a case of endobronchial paraganglioma with particular emphasis on diagnostic pathway, surgical treatment and follow-up.

Case history

A 59-year-old woman was admitted to our department for occasional haemoptysis and radiographic evidence of a left pulmonary opacity. Medical history of the patient provided no information. On physical examination, bilateral ventilation was present with no pathological findings.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest confirmed the presence of a 4-cm diameter highly vascularised para-hilar mass of the left upper pulmonary lobe, strictly adjacent to the superior pulmonary vein, with intense enhancement after contrast injection (Fig 1); neither suspected adenopathies nor distant metastases were detected. An 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed high-rate pathological radiotracer uptake (maximum standardised uptake value = 16.5) solely within the lesion.

Figure 1.

Axial chest computed tomography showing 4-cm diameter highly vascularised para-hilar mass of the left superior pulmonary lobe, strictly adjacent to the superior pulmonary vein

The patient underwent fiber-optic bronchoscopy, which demonstrated the presence of an endobronchial mass sub-occluding the left superior lobar bronchus, characterised by smooth hypervascularised mucosa (Fig 2). Considering this finding and the previous history of haemoptysis, no bioptic attempts were made.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic view of the lesion

The lesion was approached through a left lateral muscle-sparing thoracotomy and radically excised by left upper pulmonary lobectomy; a complete hilar and mediastinal lymph node dissection was performed concomitantly. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful: she was discharged on postoperative day 6.

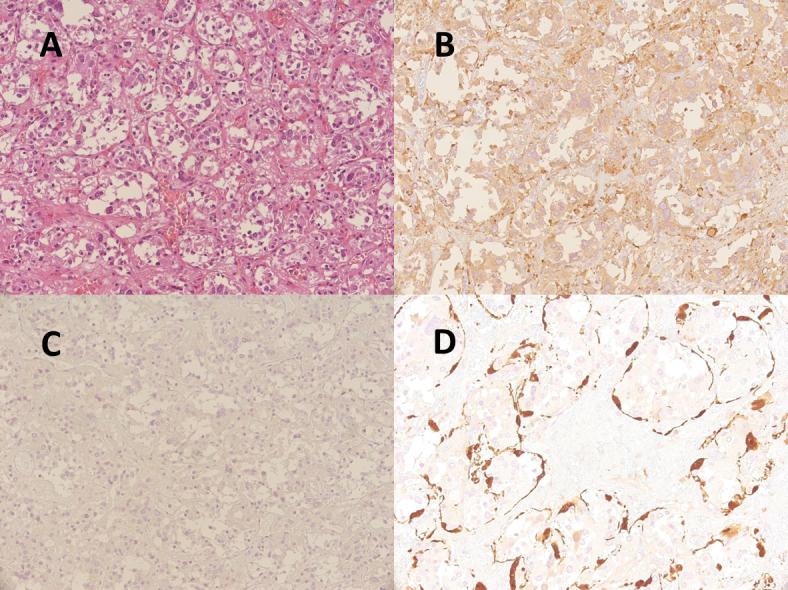

At histopathological examination (Fig 3), the mass was diagnosed as a primary endobronchial paraganglioma (synaptophysin+, S100+, CKpool–, TTF-1–); no lymph nodal metastasis was detected in N1 or N2 stations. An endocrinological evaluation indicated the execution of a catecholamine urine test and metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy to exclude the presence of extrathoracic localisations of disease. As these tests were negative, regular follow-up was instituted and the patient is currently alive, with no clinical or radiological evidence of relapse 12 months after surgery.

Figure 3.

Surgical specimen (A: haematoxylin-eosin staining, 200x) composed of two cellular types: chief cells, which have pale eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm with slightly to moderate atypical nuclei and are immunoreactive for synaptophysin (B: 200x) and negative for CKpool (C: 200x); and sustentacular cells, which have spindle-shaped nuclei with scanty cytoplasm and show immunoreactivity only for S100 (D: 400x), surrounding a nest of chief cells

Discussion

The most common paragangliar tumours are phaeocromocytomas of the adrenal medulla.1 Extra-adrenal phaeocromocytomas are termed paragangliomas; they account for about 10% of cases.2 Paragangliomas can arise from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems; in particular, those associated with the parasympathetic system are chromaffin negative, do not produce catecholamines and are not associated with hypertension or suggestive symptoms.1 Clinical presentation of these tumours is thus aspecific. Most are asymptomatic and are found incidentally on imaging studies of the chest; sometimes patients may present with cough, dyspnoea, fever, shoulder or chest pain.2

Owing to the ubiquitous distribution of paraganglia, these tumours can be found in every organ. Primary pulmonary paraganglioma was first described by Heppleston in 1958.3 To the best of our knowledge, less than 30 cases of pulmonary presentation have been documented, and localisation to the airway is even more rare. Before 2001, only five reports of tracheal paraganglioma had been described. Simoff,1 in 2001, and Aubertine,4 in 2004, first reported a lesion localised in a mainstem bronchus; Kim et al,2 in 2008, documented a case of paraganglioma in left lingular segmental bronchus. Our present case is therefore the fourth non-tracheal case described in the literature (Table 1).

Table 1.

Features of previously reported cases of endobronchial paraganglioma compared with the current case

| Reference | Age (years) | Sex | Site | Presenting symptom | Type of surgery | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simoff1 | 29 | F | Left mainstem bronchus | Recurrent haemoptysis | Endobronchial laser resection through rigid bronchoscopy | No recurrence after 36 months |

| Kim et al2 | 37 | F | Left lingular segmental bronchus | Dyspnoea, cough, haemoptysis | Left upper sleeve lobectomy | Unknown |

| Aubertine et al4 | 40 | M | Left mainstem bronchus | Recurrent obstructive pneumonia | Left mainstem bronchial sleeve resection | No recurrence after 12 months |

| Current case | 59 | F | Left upper lobar bronchus | Occasional haemoptysis | Left upper lobectomy | No recurrence after 12 months |

Occasional haemoptysis has been previously reported as presenting symptom1,2 and was present in our patient; this finding has been associated with high vascularisation, which is a specific feature of these lesions, similarly to neuroendocrine tumours.

Non-invasive imaging, such as contrast-enhanced CT, is of paramount importance in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Primary pulmonary paragangliomas usually appear as round, well-defined masses with significant enhancement after contrast injection, due to the rich blood supply and frequent closeness to pulmonary vessels;2 in our case, proximity to the left superior pulmonary vein and intense contrast enhancement added angiosarcoma into the differential diagnosis. Endobronchial paragangliomas usually appear as hypervascularised masses at bronchoscopy. Endobronchial biopsy can be dangerous. In 1963, Horree5 described a case of fatal bleeding during the procedure. Thus, in the case of clinical suspicion of paraganglioma, biopsy of a hypervascularised endobronchial lesion should be avoided.1

Final diagnosis is made upon histological examination, since these tumours show typical architecture (so-called diffuse zellballen pattern) and immunohistochemical profile (S100+ and cytokeratin–).4 Incidence of malignancy is reported to be between 10%1 and 18%.2 A paraganglioma is defined as malignant when invasion of neighbouring organs or distant metastasis are evident; any histological or biochemical feature can adequately identify malignant paragangliomas.2

Surgery is mandatory both for final diagnosis and definitive treatment of paraganglioma, since the clinical behaviour of these lesions is usually benign. In this case, the lesion was approached through a lateral muscle-sparing thoracotomy and radically excised by left upper pulmonary lobectomy. We also considered a video-assisted thoracoscopic approach, which was finally excluded. In our opinion, this procedure might not be safe, owing to the para-hilar localisation of the lesion, close to left superior pulmonary vein, and the possible differential diagnosis with angiosarcoma. Adjuvant therapies are not necessary when the presence of extrathoracic disease localisations is excluded; long-term follow up by clinical observation, urinary catecholamines dosage and imaging is suggested.2

In conclusion, this report describes a rare case of endobronchial primary pulmonary paraganglioma. Contrast enhanced CT can aid diagnosis when a rich blood supply is detected. Bioptic attempts during fiberoptic bronchoscopy should be avoided because of the high risk of potentially fatal bleeding. Surgical resection is the mainstay of both reaching a final diagnosis and definitive treatment of these tumours. An endocrinological evaluation, including a cathecolamine urine test and metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy are indicated to exclude the presence of extrathoracic localisations of disease.

References

- 1.Simoff MJ. Endobronchial paraganglioma: case report and review of the literature. J Bronchology 2001; : 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KN, Lee KN, Roh MS et al. Pulmonary paraganglioma manifesting as an endobronchial mass. Korean J Radiol 2008; : 87–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heppleston AG. A carotid-body-like tumour in the lung. J Pathol Bacteriol 1958; : 461–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubertine CL, Flieder DB. Primary paraganglioma of the lung. Ann Diagn Pathol 2004; : 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horree WA. An unusual primary tumor of the trachea. Pract Otorhinolaryngol 1963; : 125–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]