Significance

IRBIT (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor binding protein released with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate) contributes to calcium signaling, electrolyte transport, mRNA processing, genomic integrity, and catecholamine homeostasis through its interaction with multiple targets. However, how IRBIT selectively binds and regulates appropriate target molecules in a certain condition is poorly understood. In this study, we found that N-terminal variation of Long-IRBIT by splicing affected protein stability and target selectivity. In addition, IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants formed homo- and heteromultimers. N-terminal variation of IRBIT family members mediates the regulation of multiple signaling pathways.

Keywords: IRBIT, Long-IRBIT, splice variant, protein stability, protein–protein interaction

Abstract

IRBIT [inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) binding protein released with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)] is a multifunctional protein that regulates several target molecules such as ion channels, transporters, polyadenylation complex, and kinases. Through its interaction with multiple targets, IRBIT contributes to calcium signaling, electrolyte transport, mRNA processing, cell cycle, and neuronal function. However, the regulatory mechanism of IRBIT binding to particular targets is poorly understood. Long-IRBIT is an IRBIT homolog with high homology to IRBIT, except for a unique N-terminal appendage. Long-IRBIT splice variants have different N-terminal sequences and a common C-terminal region, which is involved in multimerization of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT. In this study, we characterized IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants (IRBIT family). We determined that the IRBIT family exhibits different mRNA expression patterns in various tissues. The IRBIT family formed homo- and heteromultimers. In addition, N-terminal splicing of Long-IRBIT changed the protein stability and selectivity to target molecules. These results suggest that N-terminal diversity of the IRBIT family and various combinations of multimer formation contribute to the functional diversity of the IRBIT family.

It was recently proposed that protein–protein interaction networks are scale-free, in that most of the proteins bind to one or two targets but relatively fewer “hub proteins” interact with 10 or more targets (1). The scale-free property of protein–protein interactions provides the advantages of high connectivity and robustness for physiological basis. However, dysfunction of hub proteins can lead to the impairment of whole signaling networks (2). Therefore, it is important to understand the regulatory mechanisms of hub proteins. IRBIT [inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) binding protein released with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)] is a multifunctional protein that interacts with diverse target molecules, and therefore is assumed to function as a hub protein. IRBIT was originally identified as a molecule that interacts with the intracellular calcium channel, IP3R. IRBIT binds to the IP3 binding domain of IP3R and suppresses its activation (3). However, IRBIT binds to multiple ion channels and transporters, including sodium bicarbonate cotransporter 1 (NBCe1) (4–7), cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (6–8), solute carrier family 26 member 6 (Slc26a6) (7, 8), and sodium hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3) (9–12). It also contributes to intracellular pH regulation and fluid secretion (6–8). In addition, IRBIT binds to cleavage and polyadenylation-specific factor subunit (Fip1) and modulates the polyadenylation state of specific mRNA (13). It was also reported that IRBIT regulates ribonucleotide reductase and contributes to cell cycle progression (14). Moreover, IRBIT forms signaling complexes with phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases (15). It was also reported that IRBIT contributes in apoptosis regulation (16). In the central nervous system, IRBIT binds to calcium calmodulin-dependent kinase II-α (CaMKIIα) and contributes to catecholamine homeostasis (17). Accordingly, IRBIT contributes to calcium signaling, electrolyte transport, mRNA processing, cell cycle, apoptosis, and the regulation of catecholamine homeostasis through its interaction with multiple targets. However, how IRBIT selectively binds and regulates appropriate target molecules in certain conditions and regulates various intracellular signaling pathways is poorly understood.

We previously reported the discovery of the IRBIT homolog, Long-IRBIT (18). Although Long-IRBIT has overall high homology with IRBIT, except for a unique N-terminal appendage, it has low binding affinity to IP3R. Recently, it was reported that there were splice variants of Long-IRBIT in the human transcripts database (variant 3: NM_001130722, variant 4: NM_001130723). These splice variants have different N-terminal sequences and a common C-terminal region, which is involved in multimerization of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT. Therefore, it is possible that splicing variants have different molecular properties and form a multimer with IRBIT to achieve functional diversity. In this study, we cloned mouse homologs of Long-IRBIT splice variants and characterized the expression pattern, protein stability, and regulation of several IRBIT target molecules. These results demonstrate that the N-terminal diversity of the IRBIT family and various combinations of multimer formations contribute to the functional diversity of the IRBIT family.

Results

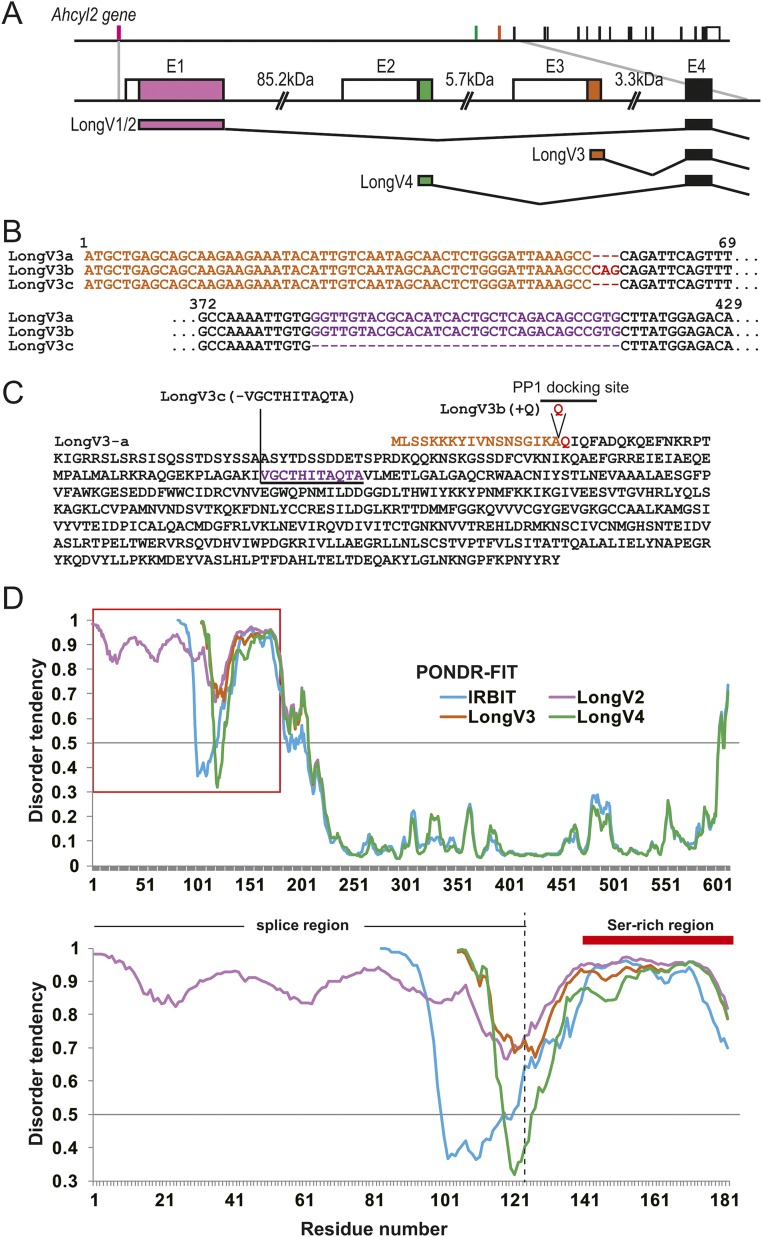

We first characterized Long-IRBIT (variant 2: NM_001130720) in 2009 (18). Novel splice variants of Long-IRBIT have been deposited in the human transcripts database (variant 1: NM_015328, variant 3: NM_001130722, variant 4: NM_001130723) (Fig. S1A). Variant 1 is highly similar to the previously characterized variant 2. We first cloned the mouse homologs of Long-IRBIT splice variant 3 (LongV3) and variant 4 (LongV4) from the mouse forebrain using specific primers (Fig. 1A and Table S1). We also obtained three different transcripts of LongV3 (3a, 3b, and 3c in Fig. S1 B and C), and characterized LongV3a, which is deposited in GenBank (NM_001171001). We previously reported that the N-terminal region of IRBIT is intrinsically highly disordered (15). Therefore, we evaluated the structural disorder of Long-IRBIT splice variants using an in silico prediction program (PONDR-FIT) (19). The N-terminal region of Long-IRBIT splice variants was highly disordered, similar to IRBIT (Fig. S1D). Therefore, the N terminus of IRBIT family proteins (IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants) belongs to the intrinsically disordered protein regions.

Fig. S1.

Long-IRBIT splice variants and structural disorder of IRBIT family. (A) Schematic illustration of Ahcyl2 gene structure and Long-IRBIT splice variants. (B) Schematic illustration of DNA sequences for 5′ CDS region of LongV3 splice variants cloned from mouse brain cDNA. (C) Schematic illustration of amino acid sequences for LongV3 splice variants. (D) In silico prediction for intrinsically disordered regions of IRBIT family. Amino acid sequences of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants were analyzed by metaprotein disorder prediction program PONDR-FIT (19). (Upper) Whole sequences of IRBIT family. (Lower) N-terminal regions of IRBIT family indicated by a red box above.

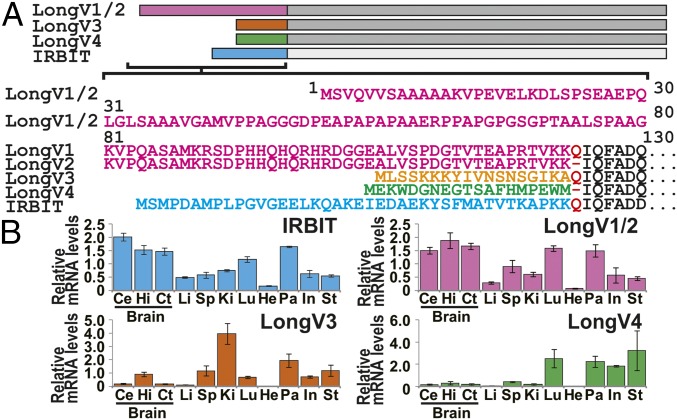

Fig. 1.

Tissue distribution of IRBIT family. (A) Schematic illustration of IRBIT family and N-terminal amino acid sequence. (B) Tissue distribution of IRBIT family mRNA expression. n = 3. Ce, cerebellum; Ct, cerebral cortex; He, heart; Hi, hippocampus; In, intestine; Ki, kidney; Li, liver; Lu, lung; Sp, spleen; St, stomach; Pa, pancreas.

Table S1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Restriction enzyme | 5′-sequence-3′ | Application |

| BamHI-LongV3-S | BamHI | ctGGATCCATGCTGAGCAGCAAGAAGAAATAC | Cloning |

| BamHI-LongV4-S | BamHI | ctGGATCCATGGAGAAGTGGGACGGTAATGAG | Cloning |

| Long-AS-XbaI | XbaI | gaTCTAGATTAATACCTGTAGTAGTTAGGC | Cloning |

| BamHI-Flag-LongV3-S | BamHI | ctGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGATGACGACGACAAGATGCTGAGCAGCAAGAAGAAATAC | Subcloning |

| BamHI-Flag-V4-S | BamHI | CtGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGATGACGACGACAAGATGGAGAAGTGGGACGGTAATGAG | Subcloning |

| BamHI-seBFP-S | BamHI | atcGGATCCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG | pcDNA3.1-seBFP-P2A vector |

| seBFP-AS-EcoRI | EcoRI | CtGAATTCTCACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG | pcDNA3.1-seBFP-P2A vector |

| BsrGI-P2A-AgeI-EcoRI-S | BsrGI | GTACAAGGGAAGCGGAGCTACTAACTTCAGCCTGCTGAAGCAGGCTGGAGACGTGGAGGAGAACCCTGGACCTACCGGTG | pcDNA3.1-seBFP-P2A vector |

| BsrGI-P2A-AgeI-EcoRI-AS | EcoRI | AATTCACCGGTAGGTCCAGGGTTCTCCTCCACGTCTCCAGCCTGCTTCAGCAGGCTGAAGTTAGTGCTCCGCTTCCCTT | pcDNA3.1-seBFP-P2A vector |

| BamHI-mRFP-S | BamHI | ctGGATCCATGGCCTCCTCCGAGGACGTC | pcDNA3.1-mRFP-P2A vector |

| mRFP-AS-NotI-BsrGI | BsrGI | CTTGTACATTGCGGCCGCGGCGCCGGTGGAGTGGCGG | pcDNA3.1-mRFP-P2A vector |

| AgeI-IRBIT-S | AgeI | ctACCGGTATGTCGATGCCTGACGCGATGC | Subcloning |

| AgeI-LongV2-S | AgeI | ctACCGGTATGTCGGTGCAGGTTGTGTCAGCCGCG | Subcloning |

| AgeI-LongV3-S | AgeI | ctACCGGTATGCTGAGCAGCAAGAAGAAATAC | Subcloning |

| AgeI-LongV4-S | AgeI | ctACCGGTATGGAGAAGTGGGACGGTAATGAG | Subcloning |

| IRBIT-AS-XbaI | XbaI | gcTCTAGATTAGTATCTGTAATAATTAGGTTTGAATGGC | Subcloning |

| HindIII-del-N-S | HindIII | caAAGCTTATGCAGATTCAGTTTGCTGACCAGA | Subcloning |

| EcoRI-NHE3-S | EcoRI | ctGAATTCATGTGGCACCGGGCTCTGGG | Cloning |

| NHE3-AS-SalI | SalI | gaGTCGACTGCATGTGTGTGGACTCGGGGGC | Cloning |

| NHE3-AS-stop-SalI | SalI | gaGTCGACTTACATGTGTGTGGACTCGGGGGC | Subcloning |

| GAPDH-S | ATACGGCTACAGCAACAGGGTG | Quantitative PCR | |

| GAPDH-AS | CTCTCTTGCTCAGTGTCCTTG | Quantitative PCR | |

| IRBIT-S | GGGACGCTACAAACAGGATGTG | Quantitative PCR | |

| IRBIT-AS | TCTGTCAGTTCTGTCAGGTGGG | Quantitative PCR | |

| LongV2-S | GAGTGGGAGCTGGTGCGAGAG | Quantitative PCR | |

| LongV2-AS | AGCTCCACCTCAGGCACCTTG | Quantitative PCR | |

| LongV3-S | GCCAACAGAAGTGCTGATGAGG | Quantitative PCR | |

| LongV3-AS | CAGCCAGCAGACAGTGACATTG | Quantitative PCR | |

| LongV4-S | GCCTGTTGCTGAAGGAAGTCTG | Quantitative PCR | |

| LongV4-AS | CTCAAAACCTCTGCCTACTACTC | Quantitative PCR | |

| Syp-S | TCTACAGGTCTGTGGGGCTGG | Quantitative PCR | |

| Syp-AS | AGACACAGCAGAGGGTCCAGG | Quantitative PCR | |

| Syn1-S | TTCATGCCGCCTGTGGTAATGC | Quantitative PCR | |

| Syn1-AS | TGCTTCCCGACTCTTCTCTTGG | Quantitative PCR | |

| Gria1-S | CGAGGGATGTGTGGAAAGAAAAC | Quantitative PCR | |

| Gria1-AS | CTTTCAGAGTTTTCCCACTGCTC | Quantitative PCR | |

| Camk2a-S | AAGTCCCTGCCCCAGTCTGAG | Quantitative PCR | |

| Camk2a-AS | GCTTGTCAGATGAGGGTGGGC | Quantitative PCR | |

| GFAP-S | CACTTGCTCGGCTGGAGGAGG | Quantitative PCR | |

| GFAP-AS | GCAATTTCCTGTAGGTGGCGATC | Quantitative PCR |

Italics and underlining indicate restriction sites for cloning. Boldface and underlining indicate Flag sequence. Boldface indicates P2A sequence.

We analyzed the mRNA expression of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants in adult mouse organs by quantitative PCR analysis using specific primers (Table S1). It was technically difficult to distinguish between Long-IRBIT splice variants 1 and 2 (LongV1 and LongV2), because the difference between LongV1 and LongV2 is only 1 aa at the splice site (Fig. 1A). IRBIT and LongV1/2 were expressed in various tissues and highly expressed in the pancreas and brain (Fig. 1B). LongV3 was mainly expressed in the kidney and LongV4 was expressed in the lung, pancreas, small intestine, and stomach. We generated a specific antibody (Ab) against LongV4. The anti-LongV4 Ab specifically recognized LongV4 of 60 kDa, but not IRBIT, LongV2, or LongV3 (Fig. S2A). We also confirmed the specificity of IRBIT Ab (20), LongV1/2 Ab (18), and pan-IRBIT Ab (18). The anti-IRBIT and anti-LongV1/2 Abs specifically recognized IRBIT and LongV2, respectively, whereas the anti–pan-IRBIT Ab recognized IRBIT, LongV2, LongV3, and LongV4 (Fig. S2B). Western blot analysis of anti-LongV4 revealed that it is highly expressed in the stomach and poorly expressed in the pancreas (Fig. S2C). Immunostaining using anti-LongV4 Ab showed that the strong immunosignal was observed in the stomach, compared with the brain (Fig. S2D). In the stomach, LongV4 was expressed in gastric parietal cells, which were stained with the proton pump HKATPase (Fig. S2E). LongV4 was expressed near the basal membrane, whereas HKATPase staining was observed around the intracellular canaliculi. These results demonstrate tissue-specific expression of Long-IRBIT splice variants. Additionally, we found that gene expression of Long-IRBIT splice variants was regulated during postnatal brain development and neuronal maturation (Fig. S2 F–M).

Fig. S2.

Validation of LongV4 specific antibody and IRBIT family expression. (A and B) Western blotting (WB) analysis of COS-7 cells expressing HA-IRBIT or HA–Long-IRBIT splice variants. The asterisk represents cross-reacting to a nonrelated molecule. (C) Tissue distribution of LongV4 protein expression. The asterisks represents cross-reacting to a nonrelated molecule. (D) Adult mouse stomach and brain section were stained with anti-LongV4 (cyan) and DAPI (magenta). (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (E) Adult mouse stomach section was stained with phalloidin (magenta), anti-LongV4 (cyan), and anti-HKATPase (white). [Scale bars, (Upper) 100 μm, (Lower) 5 μm.] Arrows indicate gastic lumen, arrowheads indicate basal membrane. (F−J) IRBIT family expression in developmental brain. (F) Schematic illustration of brain regions for quantitative PCR analysis. P0–14, postnatal day 0–14; 10w, 10 wk. (G−J) Gene expression levels of IRBIT family in each brain region, n = 3. The data are normalized as Hi-P0 is equal to 1. IRBIT was almost stable during postnatal brain development except in the cerebellum. LongV1/2 expression increased after birth in all regions, whereas LongV3 and LongV4 decreased. (K) The expression ratio of LongV1/2 (H) to LongV3 (I) or LongV4 (J) drastically changed during postnatal brain development. (L) Gene expression changes of markers for synaptogenesis [synaptophysin (Syp), synapsin I (SynI), glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 1 (Gria1), calcium calmodulin dependent kinase II alpha (CaMKIIα)] and astrocytes (GFAP) during hippocampal neuronal culture, n = 3. DIV, day in vitro. All markers for synaptogenesis increased during DIV. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (M) Gene expression changes of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants during hippocampal neuronal culture, n = 3. LongV1/2 was significantly increased at DIV 8, 12, and 16. These results indicate that gene expression of Long-IRBIT splice variants was regulated during postnatal brain development and neuronal maturation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

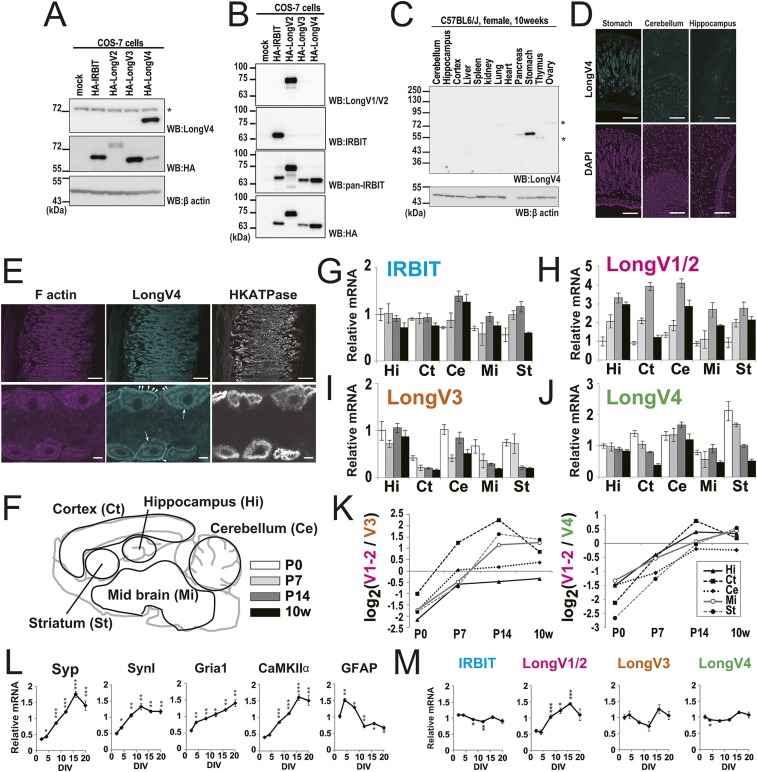

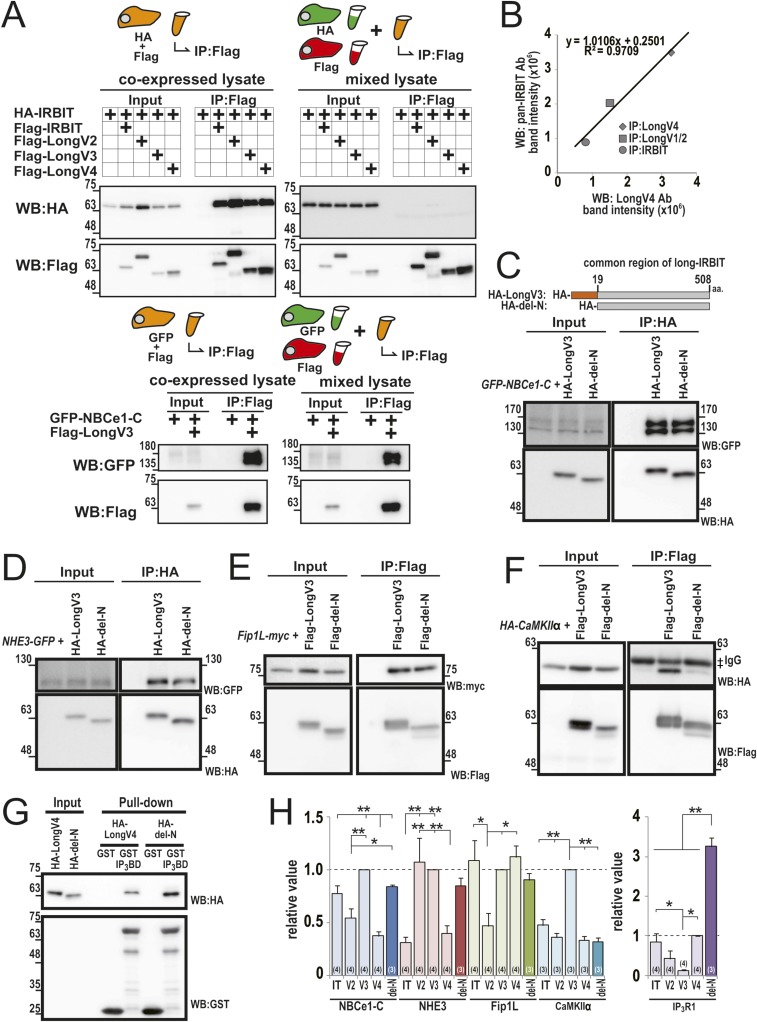

Because we previously reported that Long-IRBIT (LongV2) interacts with IRBIT through the C-terminal region (18), we conducted a coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay in COS-7 cells expressing HA- or Flag-tagged IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants. IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants were coimmunoprecipitated with each other (Fig. 2 A and B). In addition, we found that multimer formation of the IRBIT family depends on the protein synthesis and folding process (Fig. S3A; details described in SI Discussion). We also performed a co-IP assay in stomach lysates using anti-IRBIT, anti-LongV1/2, or anti-LongV4 antibodies. Endogenous IRBIT, LongV1/2, and LongV4 were coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 2C). Quantification of signal intensities of IRBIT, LongV1/2, and LongV4 detected by anti–pan-IRBIT Ab suggest that LongV4 is the dominant isoform in stomach and forms both homo- and heteromultimer, whereas IRBIT and LongV1/2 form predominantly heteromultimer with LongV4 (Fig. 2D; detailed prediction described in SI Discussion). Immunostaining of the stomach showed that IRBIT, LongV1/2, and LongV4 were expressed in gastric parietal cells (Fig. 2E). These data suggested that IRBIT family proteins form heteromultimers in stomach parietal cells.

Fig. 2.

Multimer formation of IRBIT family. IT, IRBIT; V1/2, LongV1/2; V3, LongV3; V4, LongV4. (A) Co-IP of HA-IRBIT and Flag-IRBIT family. ‡IgG bands for IP. (B) Co-IP of HA–Long-IRBITs and Flag–Long-IRBITs. (C) Co-IP assay of IRBIT, LongV1/2, and LongV4 from stomach lysates. ‡IgG bands for IP. (D) Quantification of IRBIT, LongV1/2, and LongV4 by pan-IRBIT Ab in C. (E) Adult mouse stomach section was stained with anti-IRBIT, anti-LongV1/2, or anti-LongV4 Abs (cyan), and anti-HKATPase Ab (magenta). (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

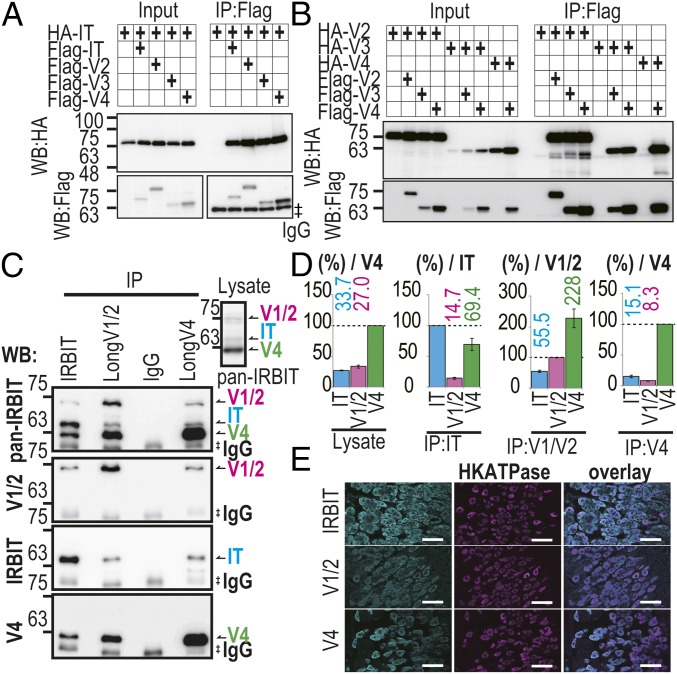

Fig. S3.

Multimer formation of IRBIT family and binding assay using N-terminal deletion mutant of Long-IRBIT. (A) Co-IP of HA-IRBIT and Flag-IRBIT family from coexpressed cells or mixed cells lysate. IRBIT families were coimmunoprecipitated from coexpressed cell lysate, but not from mixed cells lysate, whereas the interaction between LongV3 and GFP–NBCe1-C was detected from both coexpressed cells lysate and mixed cells lysate. (B) Scatter plot of expected LongV4 bands intensity detected by anti-LongV4 and anti–pan-IRBIT Abs in Fig. 2C. Although LongV3 and LongV4 cannot be discriminated using anti–pan-IRBIT Ab because of their similar molecular weights, the scatter plot suggests that the signal of LongV3/4 by anti–pan-IRBIT Ab is mostly derived from LongV4. (C) Co-IP of HA-LongV3 or HA–del-N and GFP–NBCe1-C. GFP–NBCe1-C bound strongly to HA–del-N to the same extent as HA-LongV3. (D) Co-IP of HA-LongV3 or HA–del-N and NHE3-GFP. NHE3-GFP was equally precipitated with HA–del-N and HA-LongV3. (E) Co-IP of Flag-LongV3 or Flag–del-N and Fip1L-myc. Fip1L-myc bound to Flag–del-N, to the same extent as Flag-LongV3. (F) Co-IP of Flag-LongV3 or Flag–del-N and HA-CaMKIIα. Flag-LongV3 strongly bound to HA-CaMKIIα, whereas Flag–del-N weakly bound to HA-CaMKIIα. ‡IgG bands for IP. (G) Pull-down assay of HA-LongV4 or HA–del-N and GST-tagged N-terminal region of IP3R1 (GST-IP3BD) (3). HA–del-N strongly bound to IP3R1 compared with HA-LongV4. (H) Quantification of binding assay in C–G (n = 3) together with Fig. 3F. Data were normalized by LongV3 for C–F and normalized by LongV4 for G. N-terminal deletion mutant strongly bound to target molecules (NBCe1-C, NHE3, Fip1L and IP3R1), except for CaMKIIα. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

We previously reported that Long-IRBIT (LongV2) has a lower binding affinity than IRBIT for IP3R1, although LongV2 completely conserved the critical amino acids of IRBIT required for the interaction with IP3R1 (18). Binding analysis using deletion mutants of LongV2 revealed that low affinity to IP3R1 is attributable to an inhibitory effect of the LongV2-specific N-terminal region (18). Therefore, it is possible that N-terminal splicing determines the binding affinity of the IRBIT family to target molecules. We performed a binding assay using the IRBIT family proteins and several representative target molecules (NBCe1-C, NHE3, Fip1L, CaMKIIα, and IP3R1). We previously reported that IRBIT binds to NBCe1-B (pancreatic type NBCe1) and regulates NBCe1-B activity (4). Recently, we cloned a brain type NBCe1 (NBCe1-C, GenBank accession no. AB470072.1), which has an IRBIT binding domain in common with NBCe-1B. Therefore, we investigated the interaction between NBCe1-C and the IRBIT family. COS-7 cell lysates expressing and the HA-IRBIT family and target molecule (GFP–NBCe1-C, NHE3-GFP, or Fip1L-myc) were immunoprecipitated using an anti-HA Ab. GFP–NBCe1-C bound strongly to HA-IRBIT and HA-LongV3 and bound weakly to HA-LongV2 and HA-LongV4 (Fig. 3 A and F). GFP-NHE3 bound strongly to HA-LongV2 and HA-LongV3 and bound weakly to HA-IRBIT and HA-LongV4 (Fig. 3 B and F). Fip1L-myc was equally precipitated with HA-IRBIT, HA-LongV3, and HA-LongV4, whereas HA-LongV2 bound weakly to Fip1L-myc (Fig. 3 C and F). COS-7 cell lysates expressing HA-CaMKIIα and Flag-IRBIT family proteins were immunoprecipitated using an anti-Flag Ab. HA-CaMKIIα was equally precipitated with HA-IRBIT, HA-LongV2, and HA-LongV4, whereas HA-LongV3 bound strongly to HA-CaMKIIα (Fig. 3 D and F). Finally, COS-7 cell lysates expressing HA-IRBIT family proteins were applied to the purified GST-tagged N-terminal region of IP3R1 (GST-EL) (18). HA-IRBIT and HA-LongV4 bound strongly to IP3R1 (Fig. 3 E and F). HA-LongV2 and HA-LongV3 bound weakly to IP3R1. The radar chart of relative binding affinities for each target molecule indicates that IRBIT family proteins have different binding properties (Fig. 3G). We also performed binding assay using the N-terminal deletion mutant of Long-IRBIT, which strongly bound to target molecules (NBCe1-C, NHE3, Fip1L, and IP3R1), except with CaMKIIα (Fig. S3 C–H; details described in SI Discussion). From these results, we concluded that N-terminal splicing determines the binding affinity of the IRBIT family to target molecules.

Fig. 3.

Co-IP assay for IRBIT family and target molecules and protein stability of IRBIT family. IT, IRBIT; V2, LongV2; V3, LongV3; and V4, LongV4. (A) Co-IP of HA-IRBIT family and GFP–NBCe1-C, n = 4. (B) Co-IP of HA-IRBIT family and NHE3-GFP, n = 4. (C) Co-IP of HA-IRBIT family and Fip1L-myc, n = 4. (D) Co-IP of Flag-IRBIT family and HA-CaMKIIα. ‡IgG for IP n = 3. (E) Pull-down assay of HA-IRBIT family and GST-tagged N-terminal region of IP3R1 (GST-EL), n = 4. (F) Quantification of binding assay in A–E. Data were normalized by LongV3 for A–D and normalized by LongV4 for E. R, Relative value. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (G) Radar chart of each target molecules for IRBIT family. (H) Transfected COS-7 cells with HA-IRBIT family were treated with MG-132 (10 μM) or DMSO. (I) Quantitative analysis of HA-IRBIT family in H, n = 3. ****P < 0.0001. (J) Transfected COS-7 cells with HA-IRBIT family were treated with CHX (50 μg/mL) or DMSO. (K) Quantitative analysis of HA-IRBIT family in J, n = 3. ****P < 0.0001, ####P < 0.0001.

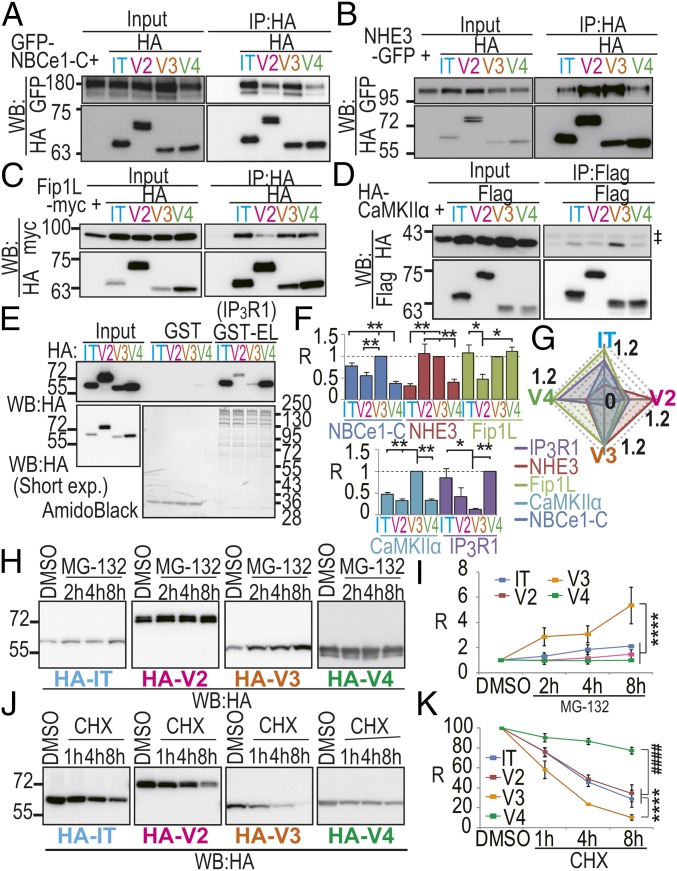

We observed that the expression level of LongV3 was lower than other variants in transfected COS-7 cells. Therefore, we investigated the effect of the proteasome inhibitor, MG-132 (10 μM), or protein biosynthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg/mL) on the expression of HA-tagged IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants. LongV3 protein markedly accumulated with MG-132 (Fig. 3 H and I). Conversely, the protein degradation rate of LongV3 after CHX treatment was significantly higher than IRBIT, LongV2, and LongV4 (Fig. 3 J and K). These data suggest that N-terminal splicing of Long-IRBIT determines protein stability. We also examined the effect of the N-terminal tag, N-terminal deletion of specific sequences, coexpression of target molecules, and the point mutant disturbing the interaction with target molecules (3, 4, 13) on MG-132 treatment (Fig. S4; details described in SI Discussion). From these results, we concluded that N-terminal splicing of Long-IRBIT determines protein stability.

Fig. S4.

Stability of IRBIT family. (A) COS-7 cells transfected with nontag, seBFP-P2A, or GFP-tagged IRBIT family were treated with MG-132. (B) Quantitative analysis of IRBIT family in A, n = 3. Nontag LongV3 protein markedly accumulated by MG-132, compared with IRBIT, LongV2, and LongV4. Interestingly, seBFP-P2A-tag and GFP-tag masked the higher accumulation rate of LongV3 by MG-132, although the seBFP-P2A–tag cleaved off after translation by endogenous protease. **P < 0.01. (C) COS-7 cells transfected with HA-LongV3 or HA–del-N were treated with MG-132. In addition, COS-7 cells transfected with HA-LongV3 and target molecules were treated with MG-132. (D) Quantitative analysis of HA-LongV3, HA–del-N and target molecules in C, n = 3. The N-terminal deletion mutant highly accumulated to the same extent as LongV3, indicating that N-terminal–specific sequences of LongV2 and LongV4 increased protein stability. Coexpression of target molecules did not affect the accumulation rate of LongV3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, N.S., no significance. (E) COS-7 cells transfected with HA-IRBIT S68A mutant, which lacks binding activity to target molecules (3, 4, 13), and comparable mutants of Long-IRBIT were treated with MG-132. (F) Quantitative analysis of HA-IRBIT family mutants in E, n = 3. LongV3 S46A mutant significantly accumulated with MG-132, compared with IRBIT S68A, LongV2 S148A, and LongV4 S46A. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

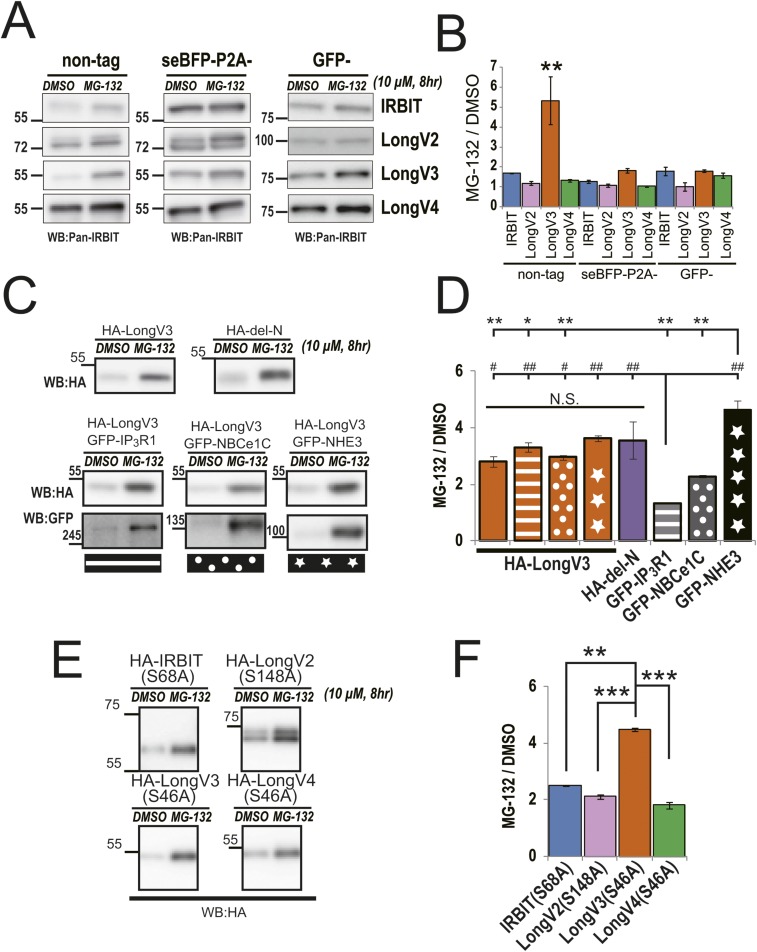

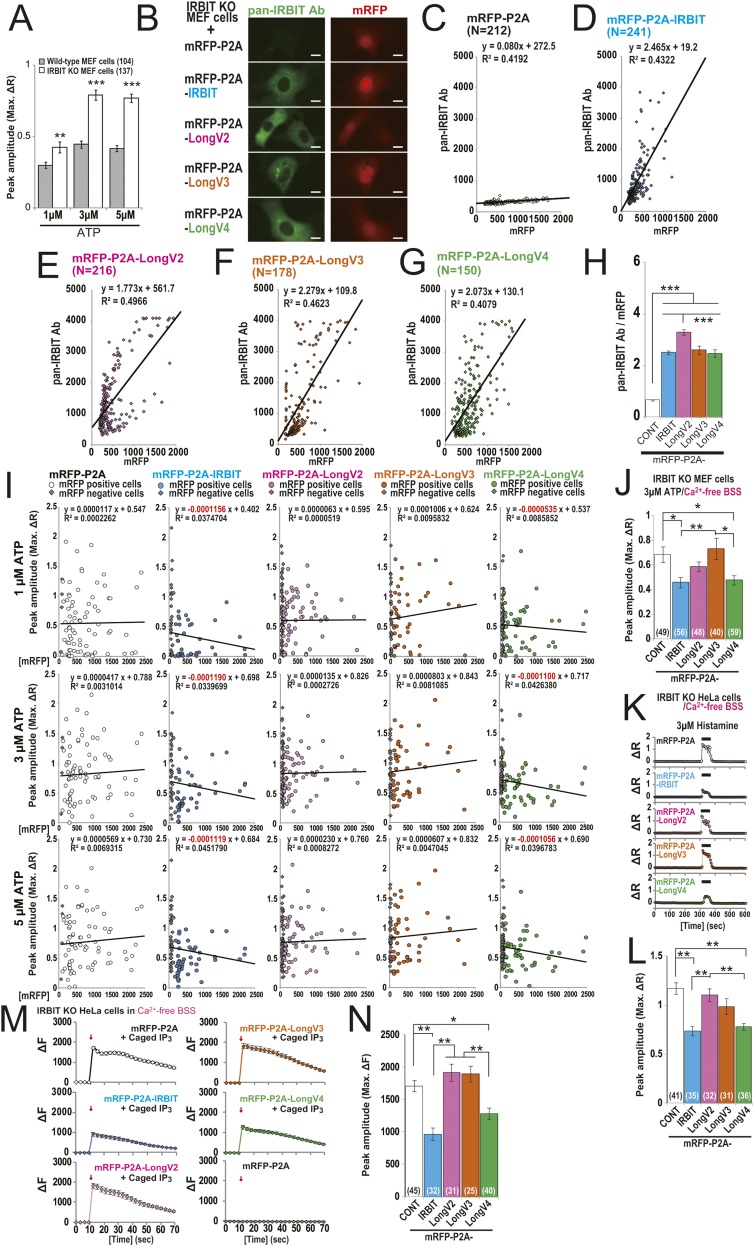

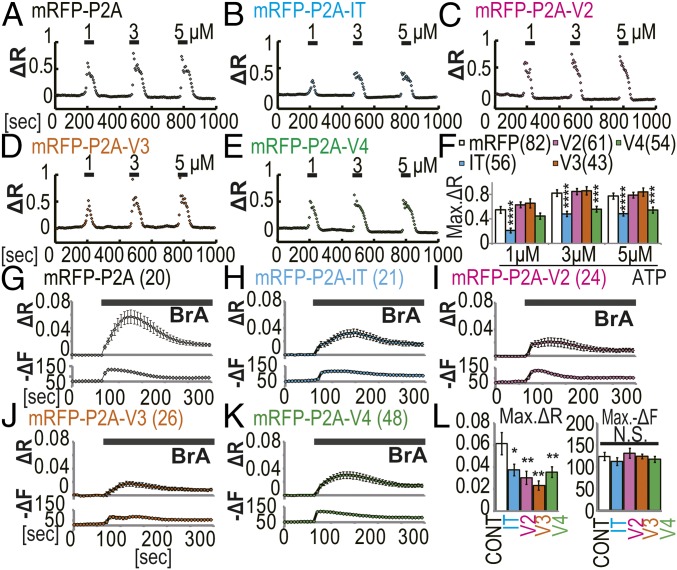

Because IRBIT and LongV4 strongly bound to IP3R1 compared with LongV2 and LongV3 (Fig. 3 E and F), we investigated the effect of IRBIT family expression on the channel activity of IP3R. Because endogenous IRBIT significantly inhibited the channel activity of IP3R (Fig. S5A) and masked the effect of IRBIT overexpression on IP3R (3), we transfected the mRFP-P2A-IRBIT family into IRBIT knockout (KO) mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells (15). The expression levels of IRBIT family were confirmed (Fig. S5 B–H). Transfected MEF cells were loaded with the calcium indicator, Fura-2, and stimulated using 1, 3, and 5 μM ATP. We found that the peak amplitude of Ca2+ transients was significantly inhibited by the expression of IRBIT and LongV4 compared with mRFP-P2A, whereas the expression of LongV2 and LongV3 did not affect Ca2+ transients (Fig. 4 A–F and Fig. S5I). Consistent results were obtained in a supplemental experiment of MEF cells in an extracellular Ca2+-free condition and of IRBIT KO HeLa cells (16) using histamine stimulation or caged-IP3 photo-uncaging (Fig. S5 J–N). These results suggest that LongV4 suppresses IP3R activity, as observed with IRBIT (3). We next investigated the effect of IRBIT family expression on CaMKIIα activation using a FRET-based CaMKIIα activity probe (Camuiα). We performed simultaneous imaging of Ca2+-ionophore (4-Bromo-A23187, BrA) -induced Ca2+ and Camuiα FRET changes in IRBIT KO MEF cells (Fig. 4 G–L). Consistent with a previous study (17), the expression of IRBIT significantly inhibited the BrA-induced Camuiα FRET change, but did not affect the Ca2+ change. In addition, the expression of Long-IRBIT splice variants also significantly inhibited the BrA-induced Camuiα FRET change, but did not affect the Ca2+ change. Notably, consistent with the strong binding affinity of LongV3 to CaMKIIα (Fig. 3 D and F), LongV3 strongly inhibits CaMKIIα activity. We concluded that all of the IRBIT family regulated CaMKIIα activity.

Fig. S5.

Effects of IRBIT family expression on IP3R activity. (A) Peak amplitude of ATP-induced Ca2+ changes in WT and IRBIT KO MEF cells. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (B) Transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells were stained with anti–pan-IRBIT Ab (green). (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (C−G) Scatter plots of mRFP intensity and immunosignal of anti–pan-IRBIT Ab in transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells. (H) Average ratio of pan-IRBIT Ab to mRFP in C−G. LongV2 ratio of pan-IRBIT Ab to mRFP was slightly higher than IRBIT, LongV3, and LongV4. ***P < 0.001. (I) Scatter plot of mRFP intensity and peak amplitude of ATP-induced Ca2+ changes. There was no significant correlation; however, we noticed that mRFP intensity of IRBIT- or LongV4-expressing cells, but not LongV2- or LongV3-expressing cells, have weak tendency to correlate negatively with peak amplitude of calcium transients. (J) Peak amplitude of 3 μM ATP-induced Ca2+ change in transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells under extracellular Ca2+-free condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (K) Representative Ca2+ imaging of 3 μM histamine-induced Ca2+ change in transfected IRBIT KO HeLa cells (16). (L) Quantitation of Ca2+ peak amplitude in transfected IRBIT KO HeLa cells. The total cell numbers are indicated. In both MEF cells stimulated with ATP and HeLa cells stimulated with histamine, IRBIT and LongV4 significantly inhibited the IP3-induced Ca2+ release compared with control cells expressing mRFP-P2A alone, whereas the expression of LongV2 and LongV3 did not have an effect. **P < 0.01. (M) Average Ca2+ imaging of IP3 uncaging-induced Ca2+ change in transfected IRBIT KO HeLa cells. Arrows, photo-uncaging stimulation (1 s). Photo-uncaging clearly induced intracellular Ca2+ change with caged-IP3, but did not induce Ca2+ change in transfected IRBIT KO HeLa cells without caged IP3. (N) Quantitation of Ca2+ peak amplitude in M. The total cell numbers are indicated. Expression of IRBIT and LongV4 significantly inhibited the peak amplitude of Ca2+ changes by IP3 uncaging, whereas the expression of LongV2 and LongV3 did not have an effect. These data support that IRBIT and LongV4 inhibited IP3R activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Fig. 4.

IRBIT family regulated ATP-induced Ca2+ release activity and CaMKIIα activation. IT, IRBIT; V2, LongV2; V3, LongV3; V4, LongV4. (A–E) Representative Ca2+ imaging of transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells. (F) Quantitation of Ca2+ peak amplitude (Max. ΔR) in transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (G–K) Simultaneously imaging of FRET and Ca2+ change in transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells. (Upper) Average FRET changes (ΔR) are shown. (Lower) Average Ca2+ responses (−ΔF) are shown. BrA: 2.5 μM. (L) Quantitation of FRET amplitude (Max. ΔR) and Ca2+ peak amplitude (Max. −ΔF). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, N.S., no significance.

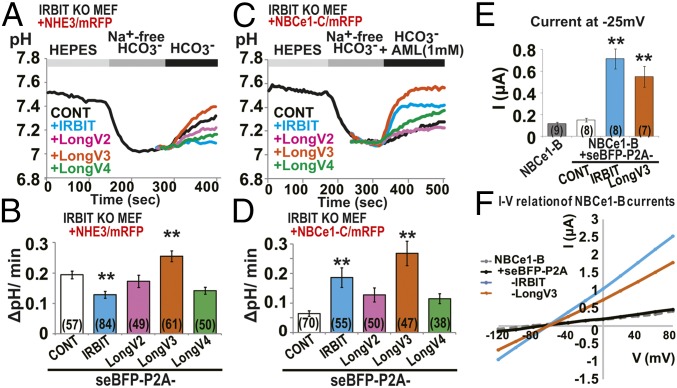

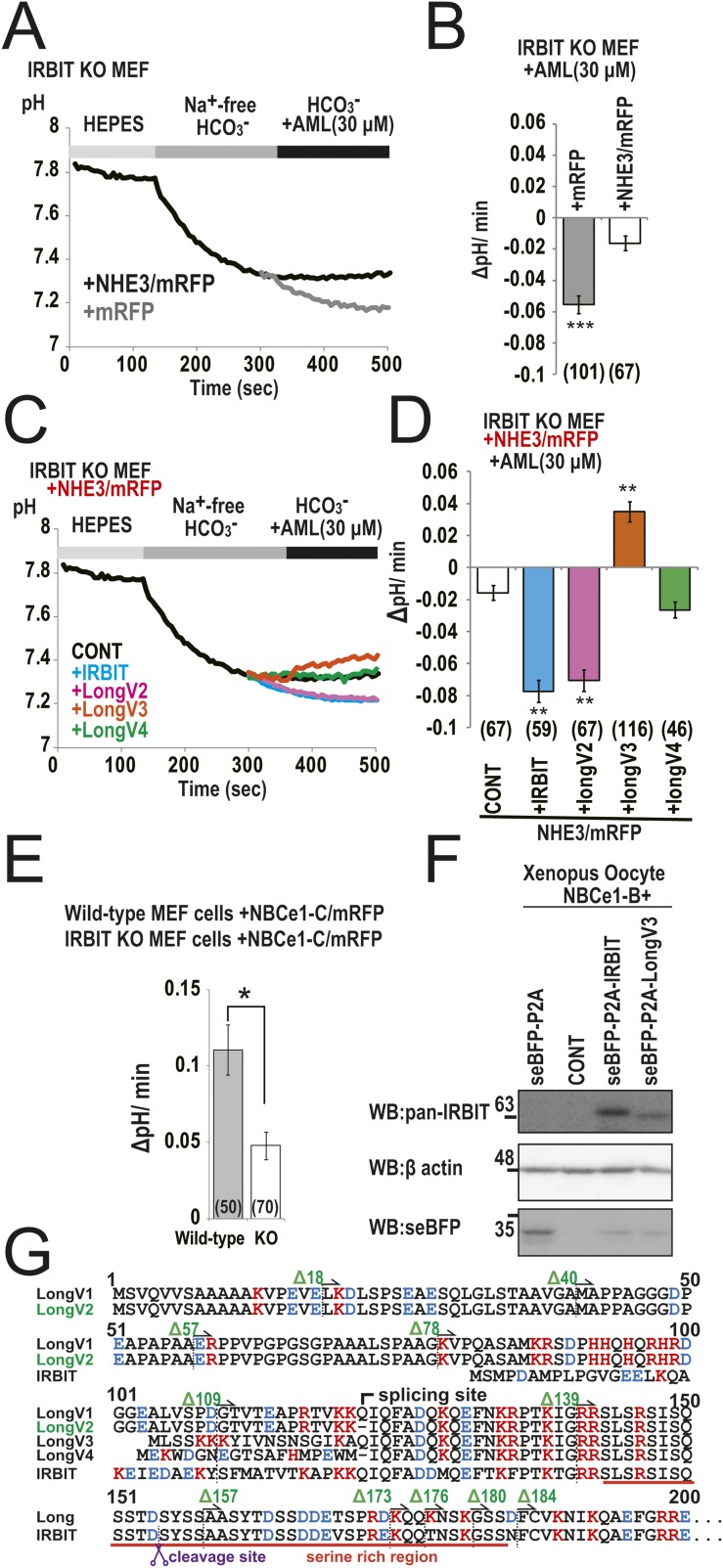

We next investigated the effect of IRBIT family expression on NHE3-dependent pH changes. IRBIT KO MEF cells were transfected with NHE3/mRFP, and seBFP-P2A-IRBIT family and Na+-dependent intracellular pH change was measured using the pH indicator 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF). He et al. previously showed that IRBIT contributed to insulin-induced or angiotensin II-induced activation of pH recovery through NHE3 transport in opossum kidney proximal tubule (OKP) cells (9–11). In addition, Tran et al. showed that IRBIT knockdown inhibited NHE3-dependent pH recovery from cell acidification in human submandibular gland cells (12). Unexpectedly, IRBIT expression significantly inhibited Na+-dependent intracellular pH change in NHE3 expressed IRBIT KO MEF cells (Fig. 5 A and B). However, LongV3 significantly activated NHE3 activity. LongV2 and LongV4 slightly inhibited NHE3 activity, but no significant difference was observed. To eliminate the effect of endogenous NHE1 activity, we performed the same experiment in the presence of 30 μM amiloride (AML), which strongly inhibits NHE1 and partially inhibits NHE3 (21). In the presence of 30 μM AML, we observed gradual acidification in IRBIT KO MEF cells expressing mRFP alone (Fig. S6A). Expression of NHE3/mRFP significantly inhibited gradual acidification in IRBIT KO MEF cells (Fig. S6 A and B). Consistent with results in the absence of AML, the expression of LongV3 activated NHE3 activity in the presence of 30 μM AML (Fig. S6 C and D). However, IRBIT and LongV2 inhibited NHE3 activity and LongV4 had no effect. From these results, we concluded that IRBIT inhibits NHE3 activity and LongV3 promotes NHE3 activity, at least in MEF cells.

Fig. 5.

IRBIT family regulated NHE3 and NBCe1 activity. (A) Representative pH imaging of transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells with NHE3/mRFP. (B) Quantitation of intracellular pH change (ΔpH/min) after switching from Na+-free to 144 mM Na+/HCO3− buffer. The total cell numbers were indicated in each graph. **P < 0.01. (C) Representative pH imaging of transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells with NBCe1-C/mRFP. (D) Quantitation of intracellular pH change (ΔpH/min) after switching from Na+-free to 144 mM Na+ HCO3− buffer with NHE1 inhibitor, AML (1 mM). **P < 0.01. (E) NBCe1-B–mediated currents in Xenopus oocyte. Influxes of anion charges were measured at a holding potential of −25 mV. **P < 0.01. (F) Current–voltage (I–V) relationship of NBCe1-B currents in oocytes. Step pulses between Vm = −120 and 80 mV were applied.

Fig. S6.

Regulation of NHE3 and NBCe1-B activities by IRBIT family. (A) Representative pH imaging of IRBIT KO MEF cells transfected with mRFP or NHE3/mRFP in the presence of NHE1 inhibitor, AML (30 μM). (B) Quantitation of intracellular pH change (ΔpH/min) after switching from Na+-free/HCO3− buffer to 144 mM Na+/HCO3− buffer. The total cell numbers are indicated. ***P < 0.001. (C) Representative pH imaging of IRBIT KO MEF cells transfected with NHE3/mRFP and seBFP-P2A or seBFP-P2A-IRBIT family in the presence of AML. (D) Quantitation of intracellular pH change (ΔpH/min) after switching from Na+-free/HCO3− buffer to 144 mM Na+/HCO3− buffer. The total cell numbers are indicated. **P < 0.01. (E) Quantitation of intracellular pH change (ΔpH/min) in WT and IRBIT KO MEF cells expressing NBCe1-C/mRFP. The total cell numbers are indicated. *P < 0.05. (F) Expression and cleavage seBFP at P2A site of IRBIT and LongV3 in Xenopus oocytes. (G) Schematic illustration of N-terminal deletion mutants for binding assay and electrophysiological analysis. N-terminal amino acid sequences are shown in different color; positive charged (red), negative charged (blue), and neutral (black) amino acids.

We examined the effect of IRBIT family protein expression on NBCe1-C activity. Because endogenous IRBIT significantly activated the NBCe1-C activity (Fig. S6E), IRBIT KO MEF cells were transfected with the expression vector NBCe1-C/mRFP and seBFP-P2A-IRBIT family and Na+-dependent intracellular pH changes were measured using BCECF. Consistent with the binding affinity (Fig. 3A), IRBIT and LongV3 significantly activated NBCe1-C, whereas LongV2 and LongV4 had no effect (Fig. 5 C and D). To further confirm the activation of NBCe1 by IRBIT and LongV3, we performed an electrophysiological analysis in Xenopus oocytes. Oocytes were injected with NBCe1-B and seBFP-P2A, seBFP-P2A-IRBIT, or seBFP-P2A-LongV3 cRNA. Expression and cleavage of seBFP at the P2A site of IRBIT and LongV3 were verified by Western blotting using pan-IRBIT and GFP Abs (Fig. S6F). Injected oocytes were then perfused with an HCO3−/CO2 solution, and the negative charge influx (current) was measured at a holding potential of −25 mV. Consistent with the pH imaging data, IRBIT and LongV3 significantly activated NBCe1-B compared with seBFP-P2A alone (Fig. 5E). We analyzed the current–voltage (I–V) relationship by applying step pulses between Vm = −120 and 80 mV. The expression of IRBIT and LongV3 markedly activated the NBCe1-B current over the entire voltage range (Fig. 5F).

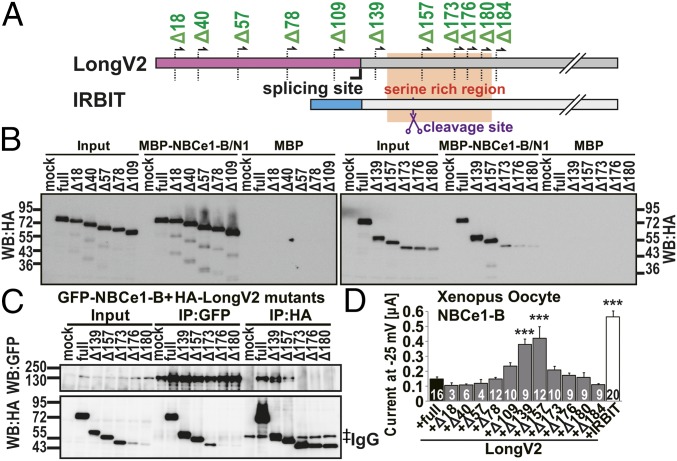

Although NBCe1-C bound weakly to LongV2 and LongV4 (Fig. 3 A and F), both did not activate NBCe1-C activity (Fig. 5 C and D). To evaluate whether the N-terminal of LongV2 disturbed the activation of NBCe1, we constructed N-terminal deletion mutants of LongV2 and performed a binding assay as well as measured NBCe1-B activity. N-terminal deletion sites are illustrated in Fig. 6A and Fig. S6G. Cell lysates of COS-7 cells expressing HA-LongV2 and deletion mutants were applied to the purified MBP tagged N-terminal region of NBCe1-B (MBP–NBCe1-B/N1) (4). Deletion mutants from Δ20 to Δ157 bound to NBCe1-B similar to full-length LongV2, whereas mutants deleted for more than 174 N-terminal amino acids no longer bound to NBCe1-B (Fig. 6B). Consistent results were obtained by co-IP assay using GFP–NBCe1-B and HA-tagged deletion mutants of LongV2 (Fig. 6C). We performed an electrophysiological analysis of NBCe1-B with LongV2 deletion mutants in Xenopus oocytes. IRBIT activated NBCe1-B, whereas the full-length HA-LongV2 did not (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, the LongV2 mutant with deleted N-terminal 139 and 157 aa (Δ139 and Δ157) significantly activated NBCe1-B compared with full-length LongV2. However, other deletion mutants were unable to activate NBCe1-B. These results indicate that N-terminal 138 aa of LongV2 and 36 aa of LongV4 disturbed their ability to activate NBCe1-B.

Fig. 6.

N-terminal of LongV2 disturbed the activation of NBCe1-B. (A) Schematic illustration of N-terminal deletion mutants for binding assay and electrophysiological analysis. (B) Pull-down assay of HA-LongV2 deletion mutants and MBP-tagged N-terminal region of NBCe1-B. (C) Co-IP of GFP–NBCe1-B and HA-LongV2 deletion mutants. ‡IgG bands for IP. (D) NBCe1-B–mediated currents at a holding potential of −25 mV in Xenopus oocyte injected NBCe1-B cRNA with full-length LongV2 (full), various LongV2 deletion mutants, or IRBIT. ***P < 0.001 compared with full-length LongV2. The total cell numbers were indicated in each graph.

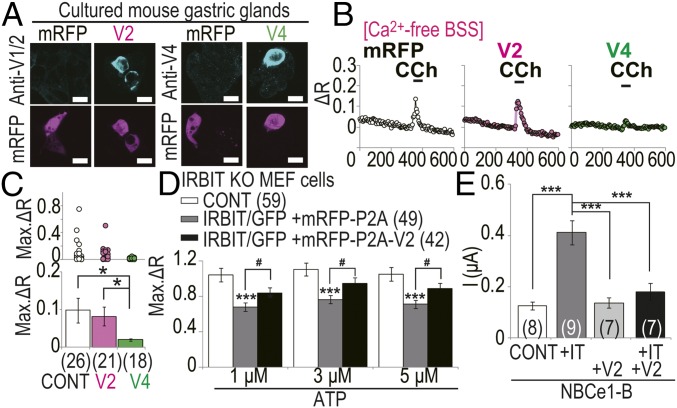

We next investigated the effects of overexpression of Long-IRBIT splicing variants on IP3R activity in stomach parietal cells, in which LongV2 and LongV4 were natively expressed (Fig. 2 C–E). Overexpression of LongV2 or LongV4 was clearly observed in mRFP+ cells (Fig. 7A). Transfected gastric glands were loaded with Fura-2, and stimulated using 100 μM carbachol (CCh) in extracellular Ca2+-free condition. Overexpression of LongV4 significantly inhibited CCh-induced Ca2+ release, compared with control cells expressing mRFP-P2A, but overexpression of LongV2 did not affect it (Fig. 7 B and C). Therefore, selectively, LongV4 regulated IP3R activity in stomach gastric glands. Finally, we examined the effect of LongV2 coexpression with IRBIT to investigate whether the heteromultimer formation of IRBIT family affects target selectivity. Because heteromultimer formation of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants was dependent on the protein synthesis and folding process (Fig. S3A), IRBIT KO MEF cells were cotransfected with the expression vector IRBIT/eGFP and mRFP-P2A or mRFP-P2A-LongV2, and ATP-induced calcium change was measured by Fura-2. The inhibition of IP3R activity by IRBIT was attenuated by LongV2 coexpression (Fig. 7D). In addition, we performed electrophysiological analysis in Xenopus oocytes to investigate the effect of LongV2 coexpression on the activation of NBCe1 by IRBIT. IRBIT significantly activated NBCe1-B compared with NBCe1-B alone, whereas LongV2 did not activate NBCe1-B (Fig. 7E). Coexpression of LongV2 with IRBIT significantly blocked NBCe1-B activation by IRBIT. From these results, we concluded that the IRBIT family forms a heteromultimer and determines target selectivity.

Fig. 7.

LongV4 inhibited CCh-induced Ca2+ release in gastric glands and LongV2 coexpression effected the regulation of IP3R and NBCe1-B by IRBIT. mRFP, mRFP-P2A; V2, mRFP–P2A-LongV2; V4, mRFP-P2A-LongV4. (A) Cultured gastric glands were transfected and stained with anti-LongV1/2 or anti-LongV4 Abs. (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (B) Representative Ca2+ imaging of transfected gastric glands. CCh: 100 μM. (C) Quantitation of Ca2+ peak amplitude (Max. ΔR). (Upper) Max. ΔR of each cell. (Lower) Average of Max. ΔR. The total cell numbers were indicated in each graph. *P < 0.05. (D) Peak amplitude (Max. ΔR) of ATP-induced Ca2+ release activity in transfected IRBIT KO MEF cells. The total cell numbers were indicated in each graph legend. ***P < 0.001 compared with control cells, #P < 0.05. (E) NBCe1-B mediated currents at a holding potential −25 mV in Xenopus oocyte. The total cell numbers were indicated in each graph. ***P < 0.001.

SI Discussion

Multimer Formation of IRBIT Family Depends on the Protein Synthesis and Folding Process.

It was previously reported that homomultimer of the purified IRBIT form E. coli was detected by gel chromatography and cross-linkage experiments (34) or crystal structure analysis (N-terminal deletion IRBIT, RCSB-PDB_3MTG, DOI: 10.2210/pdb3mtg/pdb). Homomultimer of Long-IRBIT was also observed by crystal structure analysis (N-terminal deletion Long-IRBIT, RCSB-PDB_3GVP, DOI: 10.2210/pdb3gvp/pdb). In addition, the C-terminal region of IRBIT, which is necessary and sufficient for its multimerization (3), is highly homologous (∼90% identical) to that of Long-IRBIT (18). Thus, we performed a co-IP assay of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT. IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants were coimmunoprecipitated with each other (Fig. 2 A and B). In addition, we performed the co-IP assay using the coexpressed cell lysate or the separately expressed and mixed cell lysate. As shown in Fig. S3A, the IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants were coimmunoprecipitated from the coexpressed cell lysate, but not from the mixed cell lysate. In contrast, the intermolecular interaction between LongV3 and GFP-NBCe1-C was detected in both the coexpressed cell lysate and the mixed cell lysate. Thus, if the IRBIT family were to be pulled-down using other endogenous molecules, the interaction between IRBIT families would be detected from the mixed lysate. Therefore, interactions between IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants were direct. In addition, these data indicated that the multimer composition of IRBIT family did not change in cells lysate. Therefore, we concluded that IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants form homo- and heteromultimers, and multimer formation depends on the protein synthesis and folding process.

Working Hypothesis for Prediction of IRBIT Family Multimer Composition.

Crystal structure of N-terminal truncated IRBIT (RCSB-PDB_3MTG, DOI: 10.2210/pdb3mtg/pdb) and LongV2 (RCSB-PDB_3GVP, DOI: 10.2210/pdb3gvp/pdb) showed that IRBIT and LongV2 form tetramer. On the other hand, it was also reported that purified IRBIT from E. coli formed a dimer or trimer (34). Thus, the number of multimer formation remains a matter of debate. However, if the IRBIT family formed dominantly dimer or trimer, it’s highly unlikely that more than 200% of LongV4 was coimmunoprecipitated by anti-LongV1/2 Ab (Fig. 2D). Therefore, we hypothesized that the IRBIT family dominantly form tetramer in this study. If the IRBIT family forms a tetramer, Co-IP of IRBIT (15.1%) and LongV2 (8.3%) by anti-LongV4 indicated that LongV4 formed both homo- and heteromultimers. However, Co-IP of IRBIT (55.5%) and LongV4 (228%) by the anti-LongV1/2 Ab indicated that at least one IRBIT and two or three LongV4 were included in the LongV1/2 multimer. Co-IP of LongV1/2 (14.7%) and LongV4 (69.4%) by the anti-IRBIT Ab indicated that at least one LongV4 was included in the IRBIT multimer and few LongV1/2 molecules were incorporated. Therefore, quantification of IRBIT, LongV1/2, and LongV4 detected by anti–pan-IRBIT Ab suggested that LongV4 dominantly expressed in the stomach and forms both homo- and heteromultimer, whereas IRBIT and LongV1/2 form predominantly heteromultimer with LongV4.

Binding Assay Using the N-Terminal Deletion Mutant of Long-IRBIT.

We performed a binding assay using the N-terminal deletion mutant of Long-IRBIT and several representative target molecules (NBCe1-C, NHE3, Fip1L, CaMKIIα, and IP3R1). As shown in Fig. S3 C–H, GFP–NBCe1-C bound strongly to HA–del-N to the same extent as HA-LongV3, indicating that the N-terminal–specific sequence of LongV2 and LongV4 attenuates the binding affinity to NBCe1-C. NHE3-GFP was equally precipitated with HA–del-N and HA-LongV3, indicating that the N-terminal–specific sequence of LongV4 attenuates the binding affinity to NHE3. Fip1L-myc bound to Flag–del-N, to the same extent as Flag-LongV3, indicating that the N-terminal–specific sequence of LongV2 attenuates the binding affinity to Fip1L. Flag-LongV3 strongly bound to HA-CaMKIIα, whereas Flag–del-N weakly bound to HA-CaMKIIα, suggesting that the N-terminal–specific sequence of LongV3 increases the binding affinity to CaMKIIα. Finally, HA–del-N strongly bound to IP3R1 compared with HA-LongV4, indicating that the N-terminal–specific sequences of the IRBIT family, especially LongV2 and LongV3, attenuates the binding affinity to IP3R1. These data supported that N-terminal splicing determines the binding affinity of IRBIT family to target molecules.

Stability of IRBIT Family.

We investigated the effect of N-terminal tag, N-terminal deletion of a specific sequence, and the coexpression of target molecules on the LongV3 accumulation rate by MG-132 (Fig. S4 A–D). The stability of IRBIT proteins is variant-specific with respect to nontag IRBIT family members; however, interestingly, the large-tag (seBFP-P2A–tag and GFP-tag) masked the higher accumulation rate of LongV3 by MG-132, although the seBFP-P2A–tag was cleaved off after translation by endogenous protease. Furthermore, N-terminal deletion mutant highly accumulated to the same extent as LongV3 (Fig. S4 C and D), indicating that the N-terminal–specific sequence of LongV2, and LongV4 increased protein stability. In addition, independent of the binding affinity of LongV3 to target molecules (Fig. 3 A, B, E, and F), the coexpression of target molecules did not affect the stability of LongV3. We also investigated the effect of MG-132 on the expression of the IRBIT S68A mutant, which lacks binding activity to target molecules (3, 4, 13) and comparable mutants of Long-IRBIT. The LongV3 S46A mutant showed more significant accumulation with MG-132 treatment compared with the IRBIT S68A, LongV2 S148A, and LongV4 S46A mutants (Fig. S4 E and F). These data support the idea that N-terminal splicing determines the protein stability of IRBIT family members.

Discussion

We investigated the characteristic properties of Long-IRBIT splice variants. We identified the expression of LongV4, LongV3b, and LongV3c as transcripts in the mouse brain cDNA (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1 A–C). In addition, we showed that: (i) different expression patterns of Long-IRBIT splice variants exist in various tissues and LongV4 is highly expressed in the basal membrane of stomach parietal cells; (ii) expression of Long-IRBIT splice variants drastically changed from LongV3/4 to LongV1/2 during mouse brain development and LongV1/2 expression increased during synaptogenesis of hippocampal neuronal culture; (iii) IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splice variants form homo- and heteromultimers in the stomach lysate; (iv) N-terminal splicing of Long-IRBIT changes protein stability; and (v) N-terminal splicing determines the binding affinity of IRBIT family proteins to target molecules and their selectivity to target pathways (intracellular calcium release, CaMKIIα activation, pH regulation, and so forth).

In previous studies, IRBIT contributed to insulin-induced or angiotensin II-induced activation of pH recovery through NHE3 transport in OKP cells (9–11). In addition, IRBIT knockdown inhibited NHE3-dependent pH recovery from cell acidification in human submandibular gland cells (12). However, IRBIT expression significantly inhibited Na+-dependent intracellular pH change in NHE3 expressed IRBIT KO MEF cells (Fig. 5 A and B and Fig. S6 C and D). He et al. reported that the phosphorylation of IRBIT and formation of a macrocomplex with NHE3, NHERF1, ezrin, and IRBIT contributes to insulin-dependent NHE3 activation (9, 10). Therefore, the phosphorylation state of IRBIT and the coexistence of endogenous regulatory factors or Long-IRBIT splice variants are responsible for the discrepancy between our results in IRBIT KO MEF cells and those of previous studies.

Recently, Yamaguchi et al. reported that AHCYL2 changes the apparent Mg2+ affinity of NBCe1-B in bovine parotid acinar cells under HCO3-deficient cellular conditions (22). However, Park et al. reported that the expression of LongV2 activated NBCe1-B in the same manner as IRBIT in HeLa cells (23). In this study, LongV2 has a tendency to slightly increase NBCe1-C activity, but no significant difference in IRBIT KO MEF cells was observed (Fig. 5 C and D), and it did not activate NBCe1-B in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 6D). LongV2 mutant-deleted N-terminal 139 and 157 aa significantly activated NBCe1-B compared with full-length LongV2 (Fig. 6D). It was previously reported that the N-terminal truncated IRBIT was found as part of IRBIT expressed in COS-1 cells (cleavage site is described in Fig. 6A and Fig. S6G) (24). Therefore, it may be possible that N-terminal cleavage of LongV2 by endogenous proteases convert LongV2 to its active form for NBCe1 activity. In addition, multimer formation of LongV2 with the endogenous IRBIT family are responsible for the discrepancy between the results in IRBIT KO MEF cells, Xenopus oocytes, bovine parotid acinar cells, and HeLa cells. Additional studies using various types of cells and a combination of IRBIT family proteins, target molecules, and other cofactors may help us to reveal precise regulatory mechanisms in each physiological condition.

The Long-IRBIT splicing site corresponds to a consensus protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) docking site [K/R]-X0–1-[I/V]-|P|-F (where |P| denotes any residue except proline). A number of glutamine residues (Q) in this site differ in each Long-IRBIT (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1 B and C) (LongV1: Q = 1, LongV2: Q = 0, LongV3a: Q = 1, LongV3b: Q = 2, LongV3c: Q = 1, LongV4: Q = 0). It is notable that the first lysine (K) for the consensus PP1 docking sequence is not included in LongV4. It was reported that the mutation of IRBIT at the PP1 docking site affected the binding affinity of IP3R1 (25). The PP1 docking site is located near the multiple phosphorylation sites of the IRBIT family. Therefore, it is possible that the number of glutamine residues in the Long-IRBIT splicing site affects the binding affinity for PP1 and the subsequent phosphorylation states of Long-IRBIT splice variants. It was reported that the phosphorylation state of IRBIT contributes to the binding to target molecules (3, 4, 7, 10, 13, 15). Therefore, the number of glutamine residues in the Long-IRBIT splicing site may determine the binding affinity of Long-IRBIT to target molecules.

In this study, we showed that the IRBIT family exhibits different binding affinities selectively conducive to several target pathways (Figs. 3–5). However, these data represent the mainly molecular property of homomultimer constructed by IRBIT or each Long-IRBIT splice variant. IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants form heteromultimers (Fig. 2 A–D), and LongV2 coexpression with IRBIT attenuates the effect of IRBIT (Fig. 7 D and E), indicating that the multimer formation alters target selectivity. Therefore, the combination of IRBIT family proteins may indicate functional diversity to regulate various target pathways in cells expressing multiple IRBIT family proteins. However, the results of LongV2 coexpression with IRBIT include the effect of homo- and heteromultimers. Therefore, additional studies using purified proteins composed of fixed combinations may help to reveal the detailed molecular properties of IRBIT family proteins and their target specificity.

IRBIT family proteins have diverse N-terminal regions and conserved serine-rich and C-terminal regions. All N-terminal regions of Long-IRBIT splice variants were structurally disordered, similar to IRBIT; therefore, the N-terminal regions of all IRBIT family proteins interact with various proteins. The conserved serine-rich region of IRBIT family proteins was modified by multiple phosphorylation events, and the C-terminal region forms homo- and heteromultimers of IRBIT family proteins. Therefore, N-terminal structural disorder, multiple phosphorylation events, and the combination of multimer formation serve as a base for the functional diversity of IRBIT family proteins as hub proteins, and contribute to calcium signaling, electrolyte transport, mRNA processing, cell cycle, apoptosis, and the regulation of catecholamine homeostasis through their interaction with multiple targets.

Materials and Methods

A detailed documentation of the materials and methods can be found in SI Materials and Methods. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the RIKEN guidelines for animal experiments. Every effort was made to minimize the number of animals used.

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction.

Expression vectors encoding HA-IRBIT, HA-LongV2, Flag-IRBIT, Flag-LongV2, GFP-IRBIT, GFP-LongV2, Fip1L-myc, NBCe1-B, GST-EL, Camuiα, and MBP–NBCe1-B/N1 were described previously (3, 4, 17, 18, 20). The full-length NBCe1-C (GenBank accession no. AB470072.1) was subcloned into pEGFP-C3 vector (Clontech) or pIRES2-mRFP vector (17). The full-length CaMKIIα was subcloned into pcDNA3.1zeo(+) vector (Life Technologies), including the HA sequence from the GFP-CaMKIIα vector (17). The full-length LongV3 (GenBank accession no. NM_001171001) and LongV4 (UniProtKB accession no. F8WI65) were amplified from mouse forebrain cDNA, by PCR using the primers described in Table S1 and were subcloned into pcDNA3.1zeo(+) vector including the HA or Flag sequence or pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech). The N-terminal deletion mutant of LongV3 (HA–del-N, or Flag–del-N, 19–508 aa of LongV3; common region of Long-IRBIT) were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pcDNA3.1zeo(+) vector including the HA or Flag sequence. The full-length LongV4 was subcloned into pGEX–KG (GE Healthcare) containing a prescission protease cleavage site immediately after thrombin cleavage site. The full length of the IRBIT family were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1zeo(+) vector (for nontag), pcDNA3.1–seBFP–P2A vector, or pcDNA3.1–mRFP–P2A vector. The fragment of seBFP (a kind gift from Atsushi Miyawaki, Laboratory for Cell Function Dynamics, Brain Science Institute, RIKEN, Wako, Saitama, Japan) were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1zeo(+) vector and primers for P2A sequence (Table S1) were inserted into BsrGI/EcoRI sites for the pcDNA3.1–seBFP–P2A vector. The fragment of mRFP (a kind gift from Roger Tsien, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA) was amplified by PCR and replaced with seBFP for the pcDNA3.1–mRFP–P2A vector. The full-length NHE3 was amplified from mouse kidney cDNA by PCR using the primers described in Table S1 and subcloned into the pEGFP–N1 or pIRES2–mRFP vector (17).

Antibodies.

For production of anti-LongV4 antibody, GST-LongV4 was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified using glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). GST-tag was cleaved by prescission protease (GE Healthcare). Japanese white rabbits were immunized with the full length of LongV4. The rabbit antiserum was affinity-purified against LongV4-specific peptides (V4sp–Cys–peptide: EKWDGNEGTSAFHMPEWMC) covalently coupled to thiopropyl Sepharose 6B (GE Healthcare) according to standard protocols. Rabbit anti-IRBIT Ab, rabbit anti–Long-IRBIT Ab, and rabbit pan-IRBIT Ab were described previously (18, 20). Other antibodies used were rat anti-HA Ab (3F10, Roche), mouse anti-HA Ab (12CA5, Roche), mouse anti–β-actin Ab (AC-15, Sigma), mouse anti-HKATPase Ab (1H9, MBL), mouse anti-Flag Ab (M2, F3165, Sigma), rabbit anti-Flag Ab (PA1-984B, ThermoFisher), mouse anti-GFP Ab (B-2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-GFP Ab (632592, Clontech), mouse anti–c-myc Ab (9E10, Wako), and rabbit anti–c-myc Ab (A-14, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Recombinant Protein.

Recombinant GST, GST-IP3BD (IP3R1: 224–604 aa) MBP, and MBP–NBCe1-B/N1 (NBCe1-B: 1–85 aa), were expressed in E. coli and GST-EL (IP3R1: 1–2217 aa) was expressed in Sf9 cells and purified as described previously (4, 17, 26).

Cell Culture.

IRBIT WT or KO MEF cells, IRBIT KO HeLa cells, and hippocampal neurons were described previously (16, 17, 26). Monkey kidney cell line COS-7 cells and HeLa cells were obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Nacalai) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 50 units/mL penicillin, and 0.05 mg/mL streptomycin (Nacalai).

Transfection and electroporation.

Transfection was performed as described previously (26). Transfection into COS-7 cells and HeLa cells were performed using X-tremeGENE HP (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For MEF cells, electroporation was performed using MEF 1 Nucleofector Kit (VPD-1004, Lonza) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Isolation, culture, and transfection of mouse gastric glands.

Isolation and culture of mouse gastric glands were performed as described previously (27). Briefly, ICR mice (6 wk) were fasted overnight (∼24 h) and were anesthetized with isoflurane (Pfizer). Prewarmed PBS+ [PBS + 1 mM MgCl2 + 1 mM CaCl2] were perfused via the vascular system. Isolated stomach was rinsed with PBS+ and MEM (ThermoFisher Scientific) and treated with 1 mg/mL freshly preparated collagenase type 1 (Worthington Biochemical) in MEM+ [MEM + 20 mM Hepes/pH 7.4 + 0.2% (wt/vol) BSA + 1% (wt/vol) gentamycin] 30 min in a shaking 37 °C incubator. Intact gastric glands were removed from the stomach, vigorously shaken using forceps, and were rinsed in gland rinse media [DMEM/F12 1:1 (ThermoFisher) + 1% (wt/vol) gentamycin + 1% (wt/vol) penicillin-streptomycin + 0.5 mM DTT]. Finally, gastric glands were washed in gland culture media [DMEM/F12 1:1 + 0.2% (wt/vol) BSA + 1% (wt/vol) gentamycin + 100 ng/mL EGF (Sigma) + 5 μg, 5 μg, 5 ng/mL ITSS (Sigma) + 4 ng/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma)]. Gastric glands were pipetted onto the glass-bottom dish coated with Matrigel (BD). After 1 ∼2 h, transfection was performed using TransIT-LT1 Transfection Reagent (Mirus) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [plasmid DNA 3 μg, TransIT-LT1 12 μL, optiMEM (ThermoFisher) 250 μL for 3.5-cm glass-bottom dish]. Transfection efficiency for mouse gastric glands was ∼10%.

Co-IP and Pull-Down Assay.

For IP, transfected COS-7 cells were washed with PBS and were solubilized in HNE buffer [25 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1.0% (wt/vol) Nonidet P-40 (Nonidet P-40, Nacalai Tesque), 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol] with proteinase inhibitor (complete, Roche). For IP for CaMKIIα, cells were solubilized in KR buffer [25 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.5), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM EGTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1.0% (wt/vol) TritonX-100] with proteinase inhibitor without EDTA (complete, Roche). The homogenate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was precleared with Protein-G Sepharose 4B Fastflow (Protein-G, GE Healthcare) and was incubated with the appropriate antibodies and Protein-G for 4 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed four times with HNE buffer, and proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS/PAGE sampling buffer [62.5 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 6.8, 5% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, 10% (wt/vol) glycerol, 0.2% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, and 1.5 M Urea]. For pull-down binding assay, the cell lysate of COS-7 cells expressing HA-tagged IRBIT family and truncation mutants were prepared by a similar method for IP. The cell lysate were precleared with glutathione Sepharose 4B or amylose resin (New England Biolabs) and incubated with recombinant GST- or MBP-fusion proteins and glutathione Sepharose 4B or amylose resin for 4 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed four times with HNE buffer, and proteins were eluted by SDS/PAGE sampling buffer.

To test whether the multimer formation of IRBIT and Long-IRBIT splicing variants depend on the protein synthesis and folding process, we compared the co-IP assay using coexpressed cell lysate or separately expressed and mixed cell lysate. For IP of mixed lysate, separately transfected COS-7 cells were washed with PBS and were solubilized in HNE buffer with proteinase inhibitor (complete, Roche). The homogenate were split into two tubes and mixed by appropriate combination. Mixed homogenate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was applied to co-IP assay described above.

For IP of the stomach, adult mouse stomach was homogenized by polytron (PT 10-35, KINEMATICA) and Tephrone homogenizer in homogenized buffer [5 mM Pipes-Tris (pH 6.7), 125 mM mannitol, 1 mM EDTA, 40 mM sucrose] and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatants were solubilized with 1% Triton X-100 and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min. The stomach lysate was precleared with Protein-G and was incubated with the appropriate antibodies and Protein-G for 4 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed four times with HNE buffer, and proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS/PAGE sampling buffer.

Western Blotting Analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5.0% skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) for 1 h and probed with the primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature or 16 h at 4 °C. After washing with PBST, the membranes were incubated with an appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, and signals were detected with ECL, ECL Select Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare), or Immobilon Western Detection Reagents (Millipore).

Immunostaining of IRBIT KO MEF Cells.

IRBIT KO MEF cells were transfected with mRFP-P2A or mRFP-P2A-IRBIT family by electroporation. After 24 h, cells were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) PFA in PBS for 10 min, and were permeabilized with 0.1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. After blocking with blocking solution [1.0% (wt/vol) BSA, 1.0% (vol/vol) normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories) and 0.3% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS] for 60 min at room temperature, cells were stained with rabbit anti–pan-IRBIT Ab, in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. Following three washes with PBS for 15 min in total, Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was applied for 60 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were mounted with Vectashield including DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and observed under confocal fluorescence microscopy (FV1000, Olympus).

Immunohistochemistry.

C57BL/6J mice were fasted 16 h and anesthetized with isoflurane and pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with PBS, then with 4% (wt/vol) PFA in PBS. The stomach and brain were dissected from the mice, postfixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA at 4 °C overnight, and cryoprotected by immersion in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4 °C. After being embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (50% compound in 30% sucrose-PBS; Sakura Finetechnical), the stomach and brain were frozen in isopentane chilled in liquid nitrogen. The stomach and brain sectioned at 10-μm thickness with a cryostat (CM1850, Leica Microsystems) at –18 °C to –24 °C. The sections were air-dried overnight. The sections were permeabilized with 0.3% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and blocked with blocking solution [1.0% (wt/vol) BSA, 1.0% (vol/vol) normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories) and 0.3% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS] for 60 min at room temperature. The sections were then stained with rabbit anti-LongV4 Ab, anti–Long-IRBIT (LongV1/2) Ab, anti-IRBIT Ab, and mouse anti-HKATPase Ab in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. Following three washes with PBS for 15 min in total, Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa 594- or Cy5-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, and Alexa 594-conjugated Phalloidin (for F-actin staining; Life Technologies) were applied for 60 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the sections were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and observed under confocal fluorescence microscopy (FV1000, Olympus).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis.

Total RNA was prepared from mouse organs or cultured hippocampal neurons using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) or RNeasy Mini (Qiagen) and was reverse-transcribed with ReverTraAce qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Toyobo). Expression levels were quantified by fluorescence-based real-time PCR using the ABI7900HT Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR (Toyobo) and were normalized with GAPDH as an internal standard.

Intracellular Calcium Imaging.

Intracellular calcium imaging was performed as described previously (26). Briefly mRFP-P2A or the mRFP-P2A-IRBIT family was transfected into IRBIT KO MEF cells with electroporation or IRBIT KO HeLa cells with X-tremeGENE HP, or cultured mouse gastric glands with TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent. After 24 h, cells were used for imaging. After loading the cells with 5 μM Fura-2AM (DOJINDO), imaging was performed in balanced salt solution (BSS, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 115 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM glucose with or without 2 mM CaCl2). MEF cells were stimulated with 1, 3, and 5 μM ATP to induce transiently intracellular calcium release. HeLa cells were stimulated with 3 μM histamine and cultured gastric glands were stimulated with 100 μM carbachol, which induced intracellular calcium release in rabbit parietal cells (28). Quantitation of Ca2+ peak amplitude (Max. ΔR) were analyzed. Data were expressed as the averaged amplitude of 0–50 s equal to zero for MEF cells and HeLa cells and as the averaged amplitude of 250–300 s equal to zero for gastric glands.

Intracellular Calcium Imaging with IP3 Uncaging.

IRBIT KO HeLa cells were transfected with mRFP-P2A or mRFP-P2A-IRBIT family by X-tremeGENE HP. After 48 h, cells were used for imaging. After loading the cells with 4 μM Fluo-4AM (Life technologies) and 4 μM Caged-IP3 (SiChem; cag-iso-2-145-100, 30 °C, 30 min), imaging was performed in BSS without Ca2+ through a confocal microscope (FV-1200; Olympus) with high-sensitivity GaAsP detector and a 60× (NA 1.42, PLAPON60XOil) objective. Photo-uncaging was done by a weak 405-nm laser. Quantitation of Ca2+ peak amplitude (Max. ΔF) were analyzed. Data were expressed as the averaged amplitude of 0–12 s equal to zero.

FRET and Ca2+ Imaging in MEF Cells.

FRET and Ca2+ imaging were performed as described previously (17). Briefly, FRET-based CaMKIIα probe, Camuiα was transfected into MEF cells with the mRFP-P2A or mRFP-P2A-IRBIT family by electroporation. After 18–24 h, the transfected cells were used for imaging. After loading the cells with 5 μM Indo-5F AM (DOJINDO), imaging was performed in BSS without Ca2+ through an inverted microscope (IX-81; Olympus) with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (ORCA-ER; Hamamatsu Photonics) and a 40× (NA 1.35) objective. For MEF cells, 2.5 μM BrA was added by bath application to increase the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Peak amplitude FRET (Max. ΔRFRET) and Ca2+ responses [Max. −ΔF(Indo-5F)] were analyzed. Data were expressed as the averaged amplitude of 0–50 s equal to zero.

Intracellular pH Imaging.

IRBIT WT or KO MEF cells were transfected with the NHE3-IRES-mRFP or NBCe1-C–IRES-mRFP and seBFP-P2A-IRBIT family. Transfected MEF cells were grown on the poly-l-lysine–coated glass base dish (IWAKI) and incubated with the pH indicator, BCECF (ThermoFisher). MEF cells were perfused with normal Hepes solution containing the following: 115 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM Na2SO4, 25 mM Hepes-Na (pH 7.55, NaOH/NaCl), 5.5 mM glucose. BCECF fluorescence was measured at excitation wavelengths of 440 and 490 nm and collecting the light emitted at 530 nm. After the recovery period, the cells were perfused with Na-free HCO3− solution: 119 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine-Cl (NMDG-Cl), 3 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 25 mM NMDG-HCO3−, 5.5 mM glucose; pH 7.4 equilibrated with 5% (vol/vol) CO2/95% (vol/vol) O2 gas, which induced a marked intracellular acidification becaues of CO2 entry. Subsequently, solution was exchanged to a HCO3−-Ringer solution: 115 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM Na2SO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose; pH 7.4 equilibrated with 5% (vol/vol) CO2/95% (vol/vol) O2 gas in the presence or absence of AML, which blocks the endogenous Na+/H+ exchange activity. The consequential Na+-dependent pH change after solution exchange represents the NBCe1 or NHE3 activity (29–31). Calibration was performed with 10 μM nigericine in high K+ buffer: 120 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Na2SO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 25 mM Hepes-Na at pH 6.25, 6.5, 6.75, 7.0, 7.25, 7.5, 7.75, 8.0 (32).

Oocyte Preparation.

Oocyte collection and cRNA injection were performed as previously described (29, 33). Briefly, cRNAs encoding for NBCe1-B, IRBIT, Long-IRBIT variants, and their mutants were synthesized from the appropriately linearized templates with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE high-yield Capped RNA Transcription kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Female adult Xenopus laevis were anesthetized by immersion for 30 min in a 0.1% (wt/vol) solution of tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222, Sigma). Oocytes were surgically collected from ovaries and defolliculated by incubation at room temperature for 3 h in 0.1% (wt/vol) collagenase solution. Each oocyte was injected with 5 ng of each cRNA in a total volume of 50 nL, and electrophysiological experiments were performed 3–4 d after the injection.

Electrophysiological Analysis in Xenopus Oocytes.

To measure the NBCe1-B–mediated currents in Xenopus oocytes, electrophysiological studies were performed as previously described (4, 29, 32). Briefly, oocytes were initially perfused with nominally HCO3−-free ND96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Hepes at a pH of 7.4). Then, the solution was replaced by HCO3−-containing solution (66 mM NaCl, 30 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM, CaCl2, and 5 mM Hepes at a pH of 7.4), which was equilibrated with 5% CO2 in oxygen. The NBCe1-B–mediated currents induced by the solution change were measured by the two-electrode voltage-clamp method with a model OC-725C oocyte clamp (Warner Instruments) controlled by the Clampex module of pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices). The holding potential of −25 mV was applied to monitor changes in the NBCe1-B–mediated currents. Furthermore, 20-mV step pulses from −120 mV to +80 mV during 100 ms were also applied to analyze current–voltage (I–V) relationship of the NBCe1-B–mediated currents.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical comparison between two independent groups of data were performed with the Student’s t test. Other statistical analysis was conducted using IgorPro 4.0 software (HULINKS). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Values in graphs were expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We thank the RIKEN BSI Research Resources Center for help with DNA sequencing analysis, and the RIKEN BSI-Olympus Collaboration Center for technical support; all members of our laboratories, especially Dr. Chihiro Hisatsune and Dr. Takeyuki Sugawara for fruitful discussions, Mr. Akito Nagayoshi for DNA construction, and Dr. Akitoshi Miyamoto for technical support for imaging experiment; and Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. This study was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research S 25221002 (to K.M.), for Scientific Research C 16K07075 (to K.K.), and for Scientific Research C 16K07068 (to A.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AB470072.1).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1618514114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dunker AK, Cortese MS, Romero P, Iakoucheva LM, Uversky VN. Flexible nets. The roles of intrinsic disorder in protein interaction networks. FEBS J. 2005;272:5129–5148. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi AL. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature. 2000;406:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando H, et al. IRBIT suppresses IP3 receptor activity by competing with IP3 for the common binding site on the IP3 receptor. Mol Cell. 2006;22:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shirakabe K, et al. IRBIT, an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-binding protein, specifically binds to and activates pancreas-type Na+/HCO3- cotransporter 1 (pNBC1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9542–9547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602250103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SK, Boron WF, Parker MD. Relief of autoinhibition of the electrogenic Na/HCO3 cotransporter NBCe1-B: Role of IRBIT versus amino-terminal truncation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;302(3):C518–C526. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00352.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang D, et al. IRBIT coordinates epithelial fluid and HCO3- secretion by stimulating the transporters pNBC1 and CFTR in the murine pancreatic duct. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:193–202. doi: 10.1172/JCI36983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang D, et al. IRBIT governs epithelial secretion in mice by antagonizing the WNK/SPAK kinase pathway. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:956–965. doi: 10.1172/JCI43475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park S, et al. Irbit mediates synergy between ca(2+) and cAMP signaling pathways during epithelial transport in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:232–241. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He P, et al. Restoration of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3-containing macrocomplexes ameliorates diabetes-associated fluid loss. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3519–3531. doi: 10.1172/JCI79552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He P, Klein J, Yun CC. Activation of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 by angiotensin II is mediated by inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor-binding protein released with IP3 (IRBIT) and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27869–27878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He P, Zhang H, Yun CC. IRBIT, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor-binding protein released with IP3, binds Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 and activates NHE3 activity in response to calcium. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33544–33553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805534200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran TM, et al. IRBIT plays an important role in NHE3-mediated pHi regulation in HSG cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;437:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiefer H, et al. Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor-binding protein released with inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IRBIT) associates with components of the mRNA 3′ processing machinery in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and inhibits polyadenylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10694–10705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807136200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnaoutov A, Dasso M. Enzyme regulation. IRBIT is a novel regulator of ribonucleotide reductase in higher eukaryotes. Science. 2014;345:1512–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.1251550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ando H, et al. IRBIT interacts with the catalytic core of phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type Iα and IIα through conserved catalytic aspartate residues. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonneau B, et al. IRBIT controls apoptosis by interacting with the Bcl-2 homolog, Bcl2l10, and by promoting ER-mitochondria contact. eLife. 2016;5:e19896. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaai K, et al. IRBIT regulates CaMKIIα activity and contributes to catecholamine homeostasis through tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5515–5520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503310112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando H, Mizutani A, Mikoshiba K. An IRBIT homologue lacks binding activity to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor due to the unique N-terminal appendage. J Neurochem. 2009;109:539–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue B, Dunbrack RL, Williams RW, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. PONDR-FIT: A meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:996–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ando H, Mizutani A, Matsu-ura T, Mikoshiba K. IRBIT, a novel inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor-binding protein, is released from the IP3 receptor upon IP3 binding to the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10602–10612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwark JR, et al. S3226, a novel inhibitor of Na+/H+ exchanger subtype 3 in various cell types. Pflugers Arch. 1998;436:797–800. doi: 10.1007/s004240050704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi S, Ishikawa T. AHCYL2 (long-IRBIT) as a potential regulator of the electrogenic Na(+)-HCO3(-) cotransporter NBCe1-B. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park PW, Ahn JY, Yang D. Ahcyl2 upregulates NBCe1-B via multiple serine residues of the PEST domain-mediated association. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20:433–440. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.4.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devogelaere B, et al. Binding of IRBIT to the IP3 receptor: Determinants and functional effects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devogelaere B, et al. Protein phosphatase-1 is a novel regulator of the interaction between IRBIT and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Biochem J. 2007;407:303–311. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawaai K, et al. 80K-H interacts with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors and regulates IP3-induced calcium release activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:372–380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gliddon BL, Nguyen NV, Gunn PA, Gleeson PA, van Driel IR. Isolation, culture and adenoviral transduction of parietal cells from mouse gastric mucosa. Biomed Mater. 2008;3:034117. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muto Y, Nagao T, Yamada M, Mikoshiba K, Urushidani T. A proposed mechanism for the potentiation of cAMP-mediated acid secretion by carbachol. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C155–C165. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki M, et al. Defective membrane expression of the Na(+)-HCO(3)(-) cotransporter NBCe1 is associated with familial migraine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15963–15968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008705107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson CM, Thwaites DT. Regulation of intestinal hPepT1 (SLC15A1) activity by phosphodiesterase inhibitors is via inhibition of NHE3 (SLC9A3) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1822–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan D, et al. Carbonic anhydrase II binds to and increases the activity of the epithelial sodium-proton exchanger, NHE3. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309:F383–F392. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00464.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamazaki O, et al. Functional characterization of nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in the electrogenic Na+-HCO3- cotransporter NBCe1A. Pflugers Arch. 2011;461:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satoh N, et al. A pure chloride channel mutant of CLC-5 causes Dent’s disease via insufficient V-ATPase activation. Pflugers Arch. 2016;468:1183–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1808-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]