Abstract

Background

Youth with special health care needs often experience difficulty transitioning from pediatric to adult care. These difficulties may derive in part from lack of physician training in transition care and the challenges health care providers experience establishing interdisciplinary partnerships to support these patients.

Objective

This educational innovation sought to improve pediatrics and adult medicine residents' interdisciplinary communication and collaboration.

Methods

Residents from pediatrics, medicine-pediatrics, and internal medicine training programs participated in a transitions clinic for patients with chronic health conditions aged 16 to 26 years. Residents attended 1 to 4 half-day clinic sessions during 1-month ambulatory rotations. Pediatrics/adult medicine resident dyads collaboratively performed psychosocial and medical transition consultations that addressed health care navigation, self-care, and education and vocation topics. Two to 3 attending physicians supervised each clinic session (4 hours) while concurrently seeing patients. Residents completed a preclinic survey about baseline attitudes and experiences, and a postclinic survey about their transitions clinic experiences, changes in attitudes, and transition care preparedness.

Results

A total of 46 residents (100% of those eligible) participated in the clinic and completed the preclinic survey, and 25 (54%) completed the postclinic survey. A majority of respondents to the postclinic survey reported positive experiences. Residents in both pediatrics and internal medicine programs reported improved preparedness for providing transition care to patients with chronic health conditions and communicating effectively with colleagues in other disciplines.

Conclusions

A dyadic model of collaborative transition care training was positively received and yielded improvements in immediate self-assessed transition care preparedness.

What was known and gap

Many youths with special health care needs survive to adulthood, yet effective approaches for training physicians in transition care have not been established.

What is new

An interdisciplinary transition clinic for pediatrics, internal medicine, and medicine-pediatrics residents addressed psychosocial and medical transitions, including health care navigation, self-care, and education and vocation topics.

Limitations

Single institution study; outcomes limited to self-assessment of efficacy and attitudes.

Bottom line

The transition clinic improved residents' perception of transition care preparedness.

Introduction

More than 85% of youth with special health care needs survive to adulthood and transfer care from pediatric to adult settings. Many experience difficult transitions, which may derive in part from suboptimal care they receive from health care providers without training in transition care. Transition care involves supporting these patients in mastering self-care behaviors and health care navigation skills. Close collaboration and communication between pediatrics and adult clinicians are crucial as patients transfer between settings. Despite growing awareness of the importance of these transitions, few educational programs exist to train future pediatricians and adult clinicians in transition care.1 Studies of practicing physicians and trainees demonstrate the extent of the problem.2–4 In 1 study, 18% of pediatricians reported communicating with adult providers, and in another, more than 75% of internal medicine residents reported being inadequately prepared to care for youth with special health care needs.5,6

Beyond transition care training, both child- and adult-focused trainees have limited exposure to collaborative care for youth with special health care needs, and they rarely have direct working experiences with trainees in other disciplines. In a survey we conducted of more than 470 graduate medical education (GME) trainees at our institution, a majority of pediatrics and adult trainees had never spoken with a clinician from the other specialty about a patient (personal communication, April 2016). Without such experiences, residents may make assumptions about their pediatrics or adult medicine colleagues that may widen the perceived divide between them as they move into independent practice.

The objective of this educational innovation was to implement a collaborative model for training child- and adult-focused residents in transition care to fill a substantial gap, as well as to establish a pattern of productive collaboration between pediatrics and adult medicine physicians.

Methods

We established a noncategorical interdisciplinary transitions clinic at Duke University Medical Center that served patients aged 16 to 26 years with chronic medical illnesses (eg, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy); neurodevelopmental disorders (eg, autism, intellectual disability); and mental health conditions (eg, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). Clinical services focused on transitioning to adult care and providing support to achieve independent living and effective self-care behaviors. The clinic was held weekly (4 hours), and pediatrics, internal medicine, and combined medicine-pediatrics residents participated in 1 to 4 clinic sessions during month-long ambulatory rotations.

Staffing and Logistics

The clinic was staffed by a multidisciplinary team that included young adult peer coaches, a social worker, a parent navigator, a nurse, an administrative assistant, and attending physicians with pediatrics, internal medicine, psychiatry, child psychiatry, adolescent medicine, and child neurology and neurodevelopment training. Two or 3 attending physicians supervised each session as part of their standard clinical effort, and they personally evaluated new and returning patients in addition to overseeing residents. Each attending was scheduled with 1 or 2 new consultations and between 4 and 6 return visits per session, and all encounters were billed as standard medical visits. The social worker was supported by a Duke institutional GME innovation grant and a Picker Gold GME Challenge Grant. The peer coaches were work-study students who themselves were adolescents and young adults with special health care needs. The volunteer parent navigator was a parent of a young adult with a neurodevelopmental disability who also worked as a professional advocate for families with children with disabilities. Most patients were referred from within the institution by primary care or subspecialty providers for longitudinal transition support and management of complex psychosocial challenges (eg, guardianship, treatment adherence support). Patients returned every 2 to 3 months for ongoing consultative support designed to complement other specialty and primary care services.

Resident Experience

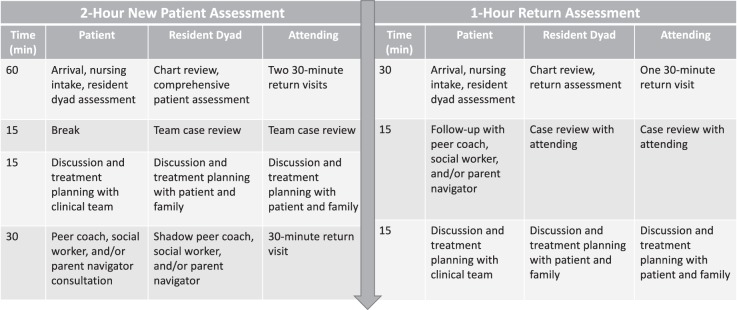

Pediatrics residents participated during their adolescent medicine rotation, and internal medicine and medicine-pediatrics residents during ambulatory rotations. Upon arrival, residents engaged in a brief didactic session about issues facing youth with special health care needs (provided as online supplementary material) and were then instructed on a rubric for conducting a medical and psychosocial transition assessment (figure 1). Pediatrics and medicine-pediatrics residents were paired with internal medicine residents to form dyads, and each dyad conducted an hour-long transition assessment. Residents typically alternated roles (primary interviewer, scribe) multiple times during each assessment and were encouraged to share the roles equitably. The residents presented each case to the team and guided further conversation with the patient to formulate a transition plan.

Figure 1.

Transition Assessment Quadrants

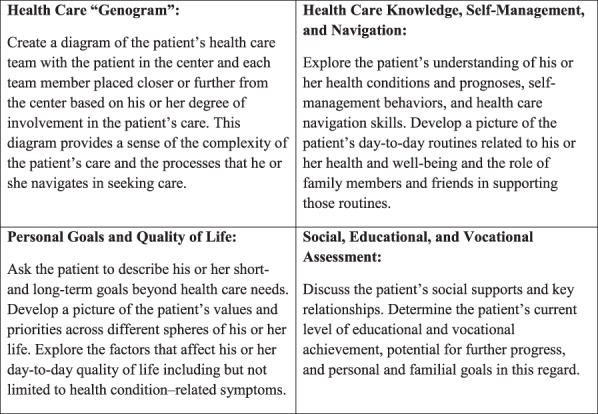

Each dyad conducted 1 to 2 new patient assessments during each session and also helped evaluate returning patients (figure 2). As time allowed, team members, including the parent navigator and peer coaches, provided additional teaching. Residents typically received 30 to 60 minutes of teaching during each session. Although all residents received core teaching around general transition concepts, additional teaching topics varied depending on the interests of the trainees. Residents also had regular opportunities to debrief about their experiences.

Figure 2.

New Patient and Return Assessment Processes

Evaluation

Residents were invited to complete a preclinic electronic survey 1 week before the first clinic session and a postclinic survey within 1 week of the end of the rotation (provided as online supplementary material). The survey assessed satisfaction with the experience, comfort with speaking with patients and other clinicians about transition, and attitudes toward youth with special health care needs. Survey items were extracted from a larger survey administered to all GME trainees at our institution, which was reviewed by 4 local experts for evidence of content validity, and by trainees for clarity.

The evaluative components of the study were approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board.

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) electronic data capture tools hosted at Duke University.7 Preclinic and postclinic responses on paired items were analyzed using paired t tests (Stata version 14, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

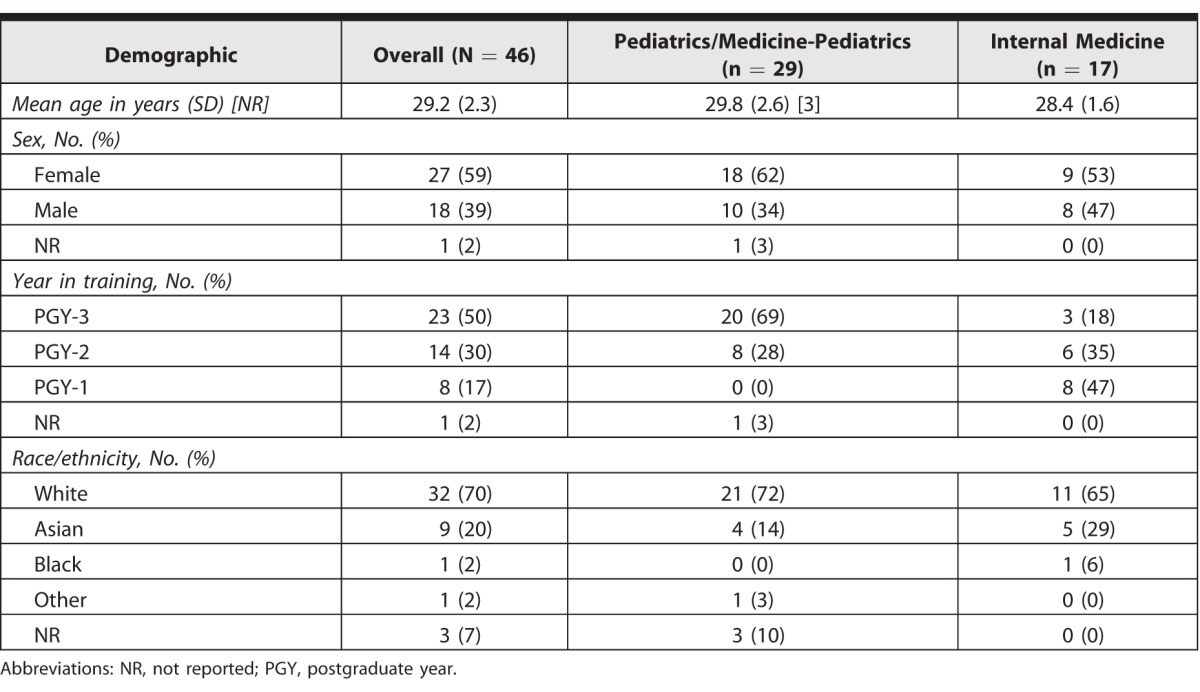

A total of 46 residents (100% of those eligible) completed a preclinic survey about their baseline attitudes and experiences. Most respondents were female and white, had some pediatrics training, and had completed at least 1 year of training at the time of participation (table 1).

Table 1.

Resident Demographics

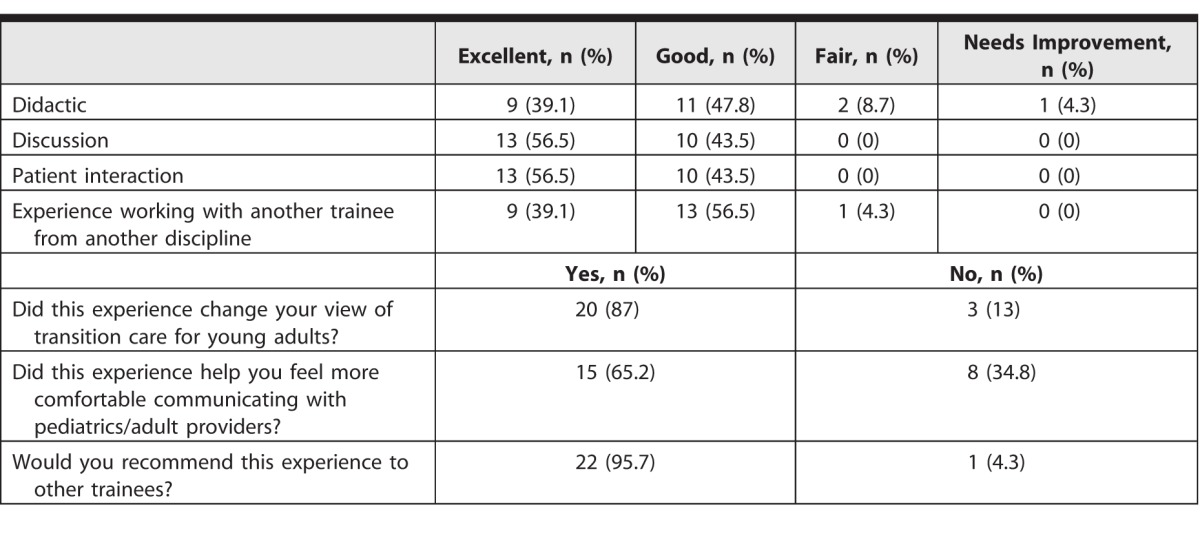

Twenty-five residents (54%) completed a postclinic survey, including 17 pediatrics and 8 internal medicine residents. A large majority of residents who completed the postclinic survey rated the clinic experience (didactics, discussions, patient interactions, and interdisciplinary collaboration) as good or excellent and reported positive changes in attitudes toward transition care, increased comfort in communicating with colleagues from other disciplines, and willingness to recommend the experience (table 2).

Table 2.

Resident Evaluation of Clinic Experience

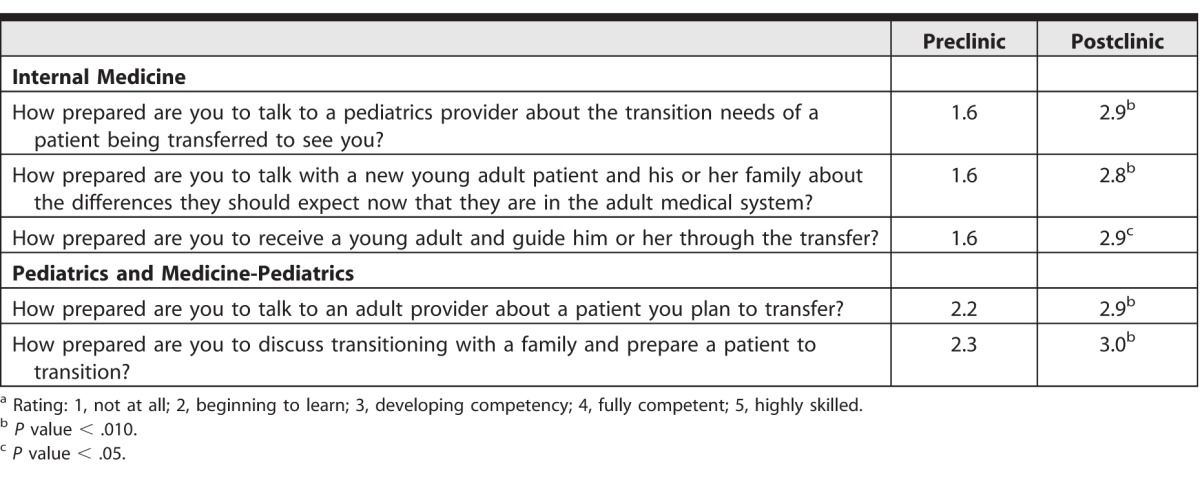

Three specific transition care preparedness items were asked of internal medicine residents, and 2 items were asked of pediatrics and medicine-pediatrics residents. Between pre- and postclinic assessment, internal medicine trainees reported statistically significant improvement in preparedness for communicating with pediatrics providers (1.6 to 2.9; range, 1–5; P < .01), counseling young adults and families (1.6 to 2.8; range, 1–5; P < .01), and receiving young adults into care (1.6 to 2.9; range, 1–5; P = .04). Pediatrics and medicine-pediatrics trainees reported statistically significant improvements in preparedness for communicating with adult providers (2.2 to 2.9; range, 1–5; P < .01) and counseling families and preparing patients to transition (2.3 to 3.0; range, 1–5; P < .01; table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Paired Preclinic and Postclinic Responsesa

In examining resident participation, we noted full attendance and high learner engagement, as well as confirmed a lack of barriers with training program coordinators. Billing receipts were adequate to support attending time when the clinic was fully subscribed.

Discussion

The dyadic model of transition care training was well received by a majority of trainees who responded to the postsurvey. Both pediatrics and adult trainees reported positive changes in self-assessed preparedness to provide transition care and engage colleagues around the care of shared patients. Changes were greatest among internal medicine trainees, possibly reflecting a greater dearth of prior relevant experiences compared with pediatrics trainees. Although statistically significant, improvements were generally small and indicated that residents did not yet feel fully competent after the experience. This is likely due to the limited and variable exposure of residents to the various transition care topics addressed in the clinic.

Of note, this innovation addressed several Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education training priorities, including the provision of appropriate and safe care, communication between colleagues, pursuit of professional ethical virtues such as health equity, and understanding of systems-based practice. The dyadic model was well suited to drawing out these training priorities given the centrality of interdisciplinary collaboration.

Key limitations of the implementation and evaluation of this innovation include its being limited to 1 setting, use of a survey to solicit self-assessed changes in attitudes and confidence, and the small number of participants who completed the postclinic survey.

Further exploration of the dyadic training model may address some of these important uncertainties by incorporating assessments (with validity evidence) that measure sustained behavioral changes and extension of the collaborative dyadic experience to longitudinal continuity clinic settings. The latter may accentuate the educational value of the dyadic model by allowing for deeper partnerships to form over time, and may provide a space for experimentation with different models for feasibility and sustainability.

This innovation was based in an established transitions clinic and funded in part by educational grants. Ensuring adequate billing and patient volumes is critical for sustainability.

Conclusion

This collaborative transition care training experience for pediatrics and adult trainees was well received by a majority of participants, and both pediatrics and adult trainees self-reported improved confidence in key transition care domains after participation.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Freed GL, Hudson EJ. . Transitioning children with chronic diseases to adult care: current knowledge, practices, and directions. J Pediatr. 2006; 148 6: 824– 827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okumura MJ, Heisler M, Davis MM, et al. . Comfort of general internists and general pediatricians in providing care for young adults with chronic illnesses of childhood. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23 10: 1621– 1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okumura MJ, Kerr EA, Cabana MD, et al. . Physician views on barriers to primary care for young adults with childhood-onset chronic disease. Pediatrics. 2010; 125 4: 748– 754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peter NG, Forke CM, Ginsburg KR, et al. . Transition from pediatric to adult care: internists' perspectives. Pediatrics. 2009; 123 2: 417– 423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burke R, Spoerri M, Price A, et al. . Survey of primary care pediatricians on the transition and transfer of adolescents to adult health care. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008; 47 4: 347– 354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mennito S. . Resident preferences for a curriculum in healthcare transitions for young adults. South Med J. 2012; 105 9: 462– 466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42 2: 377– 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.