Abstract

Objectives: Although acupuncture and microcurrent are widely used for chronic pain, there remains considerable controversy as to their therapeutic value for neck pain. We aimed to determine the effect size of microcurrent applied to lower back acupuncture points to assess the impact on the neck pain.

Design: This was a cohort analysis of treatment outcomes pre- and postmicrocurrent stimulation, involving 34 patients with a history of nonspecific chronic neck pain.

Subjects and Settings: Consenting patients were enrolled from a group of therapists attending educational seminars and were asked to report pain levels pre-post and 48 hours after a single MPS application.

Interventions and Measurements: Direct current microcurrent point stimulation (MPS) applied to standardized lower back acupuncture protocol points was used. Evaluations entailed a baseline visual analog scale (VAS) pain scale assessment, using a VAS, which was repeated twice after therapy, once immediately postelectrotherapy and again after a 48-h follow-up period. All 34 patients received a single MPS session. Results were analyzed using paired t tests.

Results and Outcomes: Pain intensity showed an initial statistically significant reduction of 68% [3.9050 points; 95% CI (2.9480, 3.9050); p = 0.0001], in mean neck pain levels after standard protocol treatment, when compared to initial pain levels. There was a further statistically significant reduction of 35% in mean neck pain levels at 48 h when compared to pain levels immediately after standard protocol treatment [0.5588 points; 95% CI (0.2001, 0.9176); p = 0.03], for a total average pain relief of 80%.

Conclusions: The positive results in this study could have applications for those patients impacted by chronic neck pain.

Keywords: : acupuncture, standard protocol, microcurrent point stimulation, neck pain

Introduction

Neck pain is a major public health problem, in terms of both personal health and overall well-being1–3 as well as indirect expense.4,5 For instance, the total cost of neck pain in The Netherlands in 1996 was estimated to be about 1% of the total health care expenditure or 0.1% of the Dutch gross domestic product.5

Acupuncture, a physical intervention that involves placement of small needles in the skin at different acupoints, has been practiced for thousands of years and is commonly used for many types of chronic pain.6–9 Science has long hypothesized for a scientific explanation of the analgesic successes of acupuncture. The literature supports that acupuncture relieves pain by regulating the autonomic nervous system,10 activating the release of beta-endorphins,11 regulating the central nervous system,12 and producing local effects on the peripheral nervous system.13 The efficacy of acupuncture for neck pain has been supported in the literature.14–16

Electroacupuncture has been used as an adjunctive pain management in acupuncture for decades,17 and may be applied invasively or noninvasively. It has been reported to analgesically outperform traditional acupuncture needles.18

Traditionally, the modality of choice for electroacupuncture has been alternating current (AC).19–21 However, there are two known types of electrical currents, AC and direct current (DC). DC is unidirectional and is applied microamp or millionth of amp (10–6 amperes) range and is called microcurrent.22–26 AC moves back and forth and is applied in the milliamperage range (10–3 amperes), and is usually called transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation or electroacupuncture.19 It is theorized that AC and DC electrocurrents have different modulating affects on the autonomic nervous system and the bodies healing processes.22,24,26

DC microcurrent therapies involve applying weak DCs (80 μA to <1 mA), and are now being increasingly recognized as an adjunct for pain relief and autonomic nervous system regulation.24,25 There is no consensus in the literature identifying the best practice measures for application of DC microcurrent to acupuncture points for chronic neck pain patients. Although sufficient evidence supports the application of AC electroacupuncture and acupuncture needles for neck pain, there is no “standardized acupuncture protocol” and limited repetitive evidence in the literature to support the use of DC electrotherapies for the treatment of neck pain. The purpose of this pilot study was to ascertain the impact of DC microcurrent point stimulation (MPS) on the neck pain levels of a cohort of patients immediately postapplication and 48 h later after a single MPS application.

Patients, materials, and methodology

This study entailed the use of MPS in 34 patients (24 female, 10 male; mean age 46 years, SD 9.76) with chronic nonspecific neck pain averaging 7.33 years (mean 7.33 years, SD 11.62), presenting to us for therapy of their neck problem. Inclusion criteria were simple: patients who were currently suffering from chronic neck pain for greater than 3 months, with a recorded >4 visual analog scale (VAS) Pain Scale score. The diagnoses of pain, location, severity, sex, previous interventions, or surgeries were not considered exclusion criteria. Informed consent was obtained to partake in treatment and the study assessments. Patient pain scores were recorded pretreatment and twice post-treatment: immediately after application and again 48 h later.

Patients, who consented to be part of the study, were enrolled from a group of professional therapists attending educational seminars run by one of us (K.A.). They were provided with a full background in acupuncture and MPS therapy. They were asked to report pain levels before and after and 48 h after a single MPS application. There were no controls in this study, as this was a cohort analysis, with the subjects acting as their own controls relating to prepain and postpain assessments.

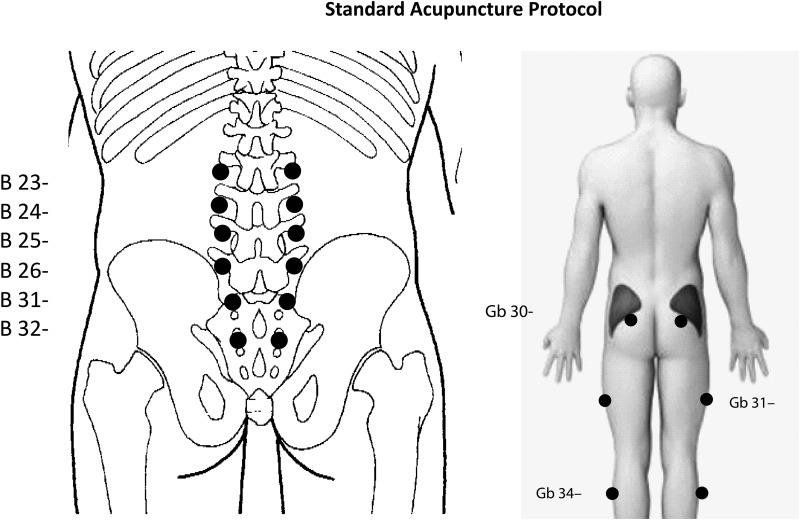

MPS was applied to standard protocol using Dolphin Neurostim (Acumed Medical LTD, Ontario, Canada) device.23 This is an FDA-approved device that applies low frequency, concentrated, microcurrent stimulation (at 10k ohms) for the relief of chronic pain.23 MPS application time was 30 sec per point, for a total of 18 points located in the lower back, hips, and legs (Fig. 1). The device was set to negative (−) polarity.

FIG. 1.

Lower paraspinal acupuncture points urinary bladder (BL) (left) and gall bladder (Gb) points (right).

VAS was used to evaluate the patient's pain. The VAS is an 11-point scale from 0 to 10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being the most intense pain imaginable.

The patient verbally selects a value that is most in line with the intensity of the pain that they have experienced in the past 24 h or is often reported as a rating during a specific movement pattern or functional task.27,28 The VAS has good sensitivity29,30 and excellent test–retest reliability.

Standard acupuncture pain protocol (SP) was developed by one of us, B.F., as treatment approach to provide a simple, easy to apply, nonpharmaceutical solution for the treatment of chronic pain. The protocol involves the application of concentrated microcurrent stimulation (MPS) to acupuncture points located in the paraspinal lumbar, hips, and legs that isolate the key nerves and muscles that influence core of the body. When these points (Fig. 1) are collectively treated with concentrated microcurrent, it has been reported that a wide variety of neuromyofascial pain syndromes can be effectively relieved in a timely basis.31,32

The practitioner applying the MPS therapy was the sole person imparting the intervention and is a coauthor of “Functional Acupuncture for Pain Management,”32 and has more than 5,000 h of practical instruction in integrative neuromyofascial pain management.

The aim of this cohort preliminary study was to evaluate whether

(1) MPS, when applied to standard protocol, can modulate VAS pain scale in patients suffering with chronic neck pain,

(2) MPS applied to standard protocol is a valid option for the nonpharmacological pain management of neck pain conditions.

Statistical analyses were done by a third party freelance statistician using SPSS software.

Results

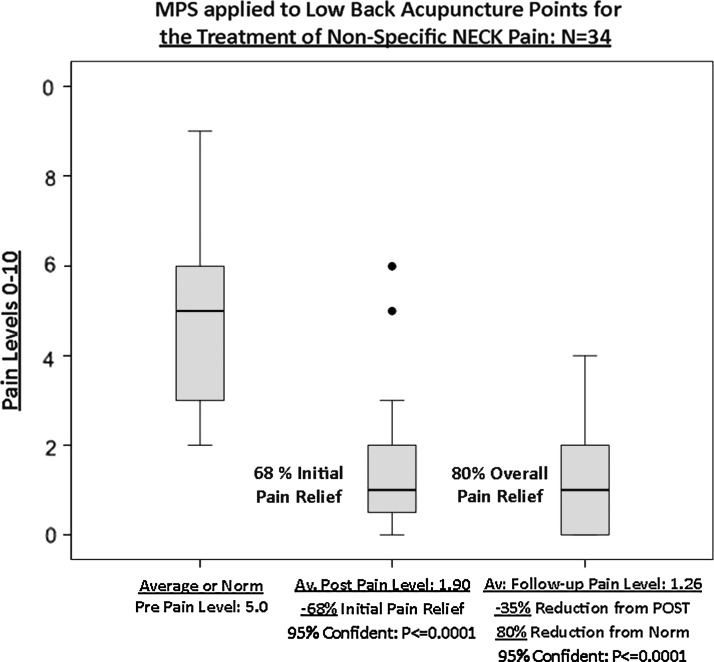

The VAS response of an N = 34 patient sample with chronic neck pain having MPS applied to lower back acupuncture points reflected an initial 68% reduction in pain [3.9050 points; 95% CI (2.9480, 3.9050); p = 0.0001], immediately postapplication and another 35% reduction in pain [0.5588 points; 95% CI (0.2001, 0.9176); p = 0.03], between post-treatment and the 48-h follow-up, for a total average pain relief of 80% (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Pain Statistics for the 34 Patients in the Cohort Study

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain level before treatment (0–10) | 34 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 5.015 | 1.7858 |

| Pain level after treatment (0–10) | 34 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 1.588 | 1.4432 |

| Follow-up pain level (0–10) | 34 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 1.029 | 1.1210 |

FIG. 2.

Neck pain scores before, immediately after, and 2 days after treatment with MPS applied to low neck and gall bladder meridian. MPS, microcurrent point stimulation.

Discussion

Chronic neck pain often equates to stress and pain that can make our daily lives miserable, and can lead to significantly impaired physical health.2,4,5 Neck pain can be difficult to diagnose and even harder to treat.

Conventional management now includes advice to stay active and continue daily activities, exercise therapy, analgesics (e.g., paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids), muscle relaxants, corticosteroid spinal injections, and referral for consideration of surgery. However, there is a lack of strong evidence of effectiveness for most of these interventions.33–35

Literature suggests that both acupuncture and physiotherapy are similarly effective for neck pain,36with an average reduction of 40%–50% in mean pain scores.37,38

The data in this cohort study clearly show that the application of MPS to standard back protocol provided statistically significantly improved pain outcomes, both immediately postapplication and 48 h follow-up for the treatment of nonspecific neck pain. Although it is well supported that abdominal exercising and improved core strength reduce neck pain,39,40 the consistency of neck pain outcomes produced through the treatment of acupuncture points of the standard protocol suggests that there may be a stronger relationship between neck pain and lower back and leg acupuncture points than the literature reports. It is of interest that the effect of a single application as per protocol continued to show further pain reduction at the 48-h postevaluation. How long this effect persists needs further study and will help to set guidelines for the frequency of MPS therapy.

It is suggested that low-amplitude DC current mimics human biocellular communications, and its application may produce regulation of the autonomic nervous system, resulting in body wide therapeutic benefits.22,24 It is also further suggested that low-frequency DC microcurrent may activate the pituitary to release endorphins.11 Both these biochemical processes may provide a plausible explanation for the prolonged pain relief after DC microcurrent and is an area where future research is required. We have already reported, in a single case study, a modification in autonomic nervous system parameters (sympathetic and parasympathetic balance) parallel to a reduction in pain score in a patient with postconcussion symptomology using MPS.24 It is possible that this same mechanism of action is at play in this cohort analysis, as the pain was not at the same location; this has to be confirmed in other patients.

Since there were no controls within this study design, it is difficult to determine whether the point selection process or the microcurrent therapy, or a combination of both, was responsible for the significantly improved pain outcomes. Further study is needed in this direction to determine roles of efficacy between these modalities.

In conclusion, this study showed MPS provided significant (62%) overall improvements in patient pain levels immediately after initial treatment, and a further significant (30%) at the 2-day follow-up, for a total 80% pain relief overall improvement when applied to a standard protocol in patients with chronic neck pain, suggesting a possible future role for these modalities in the management of nonspecific neck pain.

Conclusions

This study showed that MPS provided statistically significant 68% improvement (p ≤ 0.0001) in patient pain levels immediately after initial treatment, and a further statistically significant 35% (p ≤ 0.0001) at the 2-day follow-up, for a total 80% pain relief. These significant changes help validate the potential application of MPS to standard protocol as an option to clinicians treating patients with chronic neck pain. However, long-term further investigation is warranted with a larger focus group to confirm these results and to assess their duration.

Acknowledgment

Statistical analyses were done by a third party freelance statistician using SPSS software.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L. The treatment of neck and low neck pain: Who seeks care? who goes where. Med Care 2001;39:956–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daffner SD, Hilibrand AS, Hanscom BS, et al. Impact of neck and arm pain on mean health status. Spine 2003;28:2030–2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toomingas A. Characteristics of pain drawings in the neck–shoulder region among the working population. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1999;72:98–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassols A, Bosch F, Banos JE. How does the general population treat their pain? A survey in Catalonia, Spain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:318–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borghouts JA, Koes BW, Vondeling H, Bouter LM. Cost-of-illness of neck pain in The Netherlands in 1996. Pain 1999;80:629–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1444–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinman RS, McCrory P, Pirotta M, et al. Acupuncture for chronic knee pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:1313–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witt C, Brinkhaus B, Jena S, et al. Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomised trial. Lancet 2005;366:136–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Méndez C, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: A randomised controlled study. Pain 2006;126:245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Shi G, Xu Q, et al. Acupuncture effect and central autonomic regulation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang RS, Pomeranz B. Electroacupuncture analgesia could be mediated by at least two pain-relieving mechanisms; endorphin and non-endorphin systems. Life Sci 25: 1957–1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu MT, Hsieh JC, Xiong J, et al. Central nervous pathway for acupuncture stimulation: Localization of processing with functional MR imaging of the brain—Preliminary experience. Radiology 212:133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schröder S, Liepert J, Remppis A, Greten JH. Acupuncture treatment improves nerve conduction in peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol 14:276–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu LM, Li JT, Wu WS. Randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for neck pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:133–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White AR, Ernst E. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for neck pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trinh KV, Graham N, Gross AR, et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;:CD004870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine An Outline of Chinese Acupuncture. Beijing, China: Foreign Languages Press, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue M, Nakajima M, Hojo T, et al. Spinal nerve root electroacupuncture for symptomatic treatment of lumbar spinal canal stenosis unresponsive to standard acupuncture: A prospective case series. Acupunct Med 2012;30:103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson AJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Clinical Electrophysiology: Electrotherapy and Electrophysiologic Testing (3rd edn). New York: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ezzo JM, Richardson MA, Vickers A, et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; April 19:CD002285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dang Y. Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Beijing, China: Academy Press, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong K. Electrotherapy exposed. Rehab Management, USA. www.rehabpub.com/2016/01/electrotherapy-exposed, 2016

- 23.Dolphin DC-EA, FDA 510K. Online document at: www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/K133789.pdf

- 24.Chevalier A, Armstrong K, Norwood-Williams C, Gokal R. DC electroacupuncture effects on scars and sutures of a patient with postconcussion pain. Med Acupunct 2016;28:223–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMakin CR. Microcurrent therapy: A novel treatment method for chronic low back myofascial pain. J Bodywork Movement Ther 2004;8:143–153 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng N, Van Hoof H, Bockx E, et al. The effects of electric currents on ATP generation, protein synthesis, and membrane transport of rat skin. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982;171:264-272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krebs EE, Carey TS, Weinberger M. Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1453–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: A review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:798–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen M, McFarland C. Increasing the reliability and validity of pain intensity measurement in chronic pain patients. Pain 1993;55:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Arthritis Care & Research 63, S11, November 2011, S240–S252 Measures of Adult Pain Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Chevalier A, Armstrong K, Gokal R. Microcurrent point stimulation applied to acupuncture points for the treatment of non-specific lower back pain. HSOA J Altern Complem Integr 2016; 2:016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armstrong K, Clark JA, Durant J, et al. Functional Acupuncture for Pain Management (15th edn). 05/13. ISBN 978-0-9681714-4-8, Toronto: Acumed Publishing [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, et al. Treatment of neck pain: Noninvasive interventions. Eur Spine J 2008;17(Suppl 1):123–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreira ML. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2015;350:h1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Deyo RA, Shekelle PG. A Review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety, and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy, and spinal manipulation for back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.David J, Modi S, Aluko AA, et al. Chronic neck pain: A comparison of acupuncture treatment and physiotherapy. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:1118–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coan RM, Wong G, Coan PL. The acupuncture treatment of neck pain: A randomized controlled study. Am J Chin Med 1982;9:326–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blossfeldt P. Acupuncture for chronic neck pain—A cohort study in an NHS pain clinic. Online document at: http://aim.bmj.com/on Accessed December10, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Ingram P. Strength training surprises. Why building muscle is easier, better, and more important than you thought, and its vital role in injury rehabilitation. Online document at: PainScience.com Accessed November2016

- 40.McCaskey M, Wirth B., C. Suica Z., de Bruin E.D. Effects of proprioceptive exercises on pain and function in chronic neck- and low back pain rehabilitation: A systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 2014;15:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]