Sacrectomy is used in the management of sacral or advanced pelvic tumours. A sacral hernia is a rare complication of the procedure.

CASE HISTORY

A man aged 68 underwent resection of a sacral chordoma. The tumour involved all sacral segments and nerve roots below S1, therefore the sacrum was divided at the S1/S2 junction. The anus and rectum were excised, and an end colostomy was fashioned in the left iliac fossa. Postoperatively he developed a sacral wound infection that required formal incision and drainage. He also had a prolonged ileus.

Four months later he reported sacral pain and swelling, and on examination he had a large sacral hernia. Initially he refused surgical repair, but 2 years later he developed gallstone pancreatitis and requested sacral hernia repair at the time of his open cholecystectomy. The hernia was repaired via a transabdominal approach. The hernial sac contained small intestine, which was reduced, and two sheets of polypropylene mesh were used to repair the hernial defect and reconstruct the pelvic floor (Figures 1 and 2). The caecum and omentum were used to cover the mesh, to lessen the risk of small-bowel adhesion. A single suction drain was used and prophylactic antibiotics were administered. There were no postoperative complications and at 2-year follow-up there was no evidence of hernial recurrence.

Figure 1.

Representation of pelvic floor reconstruction: first layer of mesh placed in pelvis and sutured anteroposteriorly to the bony pelvis

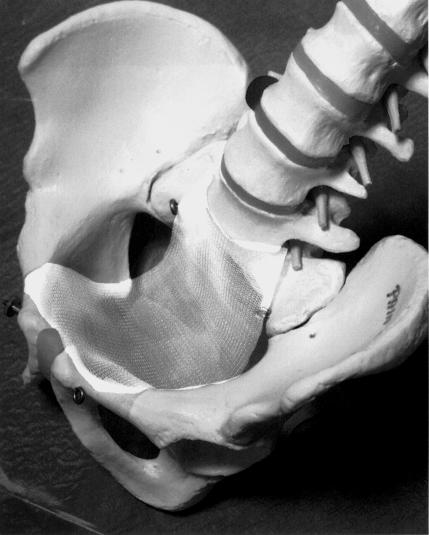

Figure 2.

Second layer of mesh placed on top of, and sutured to, the first layer. Laterally, it was sutured to the iliac fascia

COMMENT

Complications of sacrectomy include haemorrhage, infection, neurological injury affecting bowel, bladder, or lower limb function, and weakening of the pelvic ring thus impairing weightbearing and mobilization1. There have been few reported cases of sacral hernia repair1,2,3,4, although the incidence of symptomatic hernias occurring in the perineal region following abdominoperineal excisions of the rectum and pelvic exterations has been reported as 1% and 3%, respectively5. Sacral hernias usually present with pain and swelling in the sacral region. They can cause bowel or bladder disturbance depending on the contents of the hernial sac. These symptoms are often improved by application of pressure over the hernia. It has been suggested that damage to the S2-S4 sacral nerves during sacrectomy predisposes to sacral hernia formation by denervating the levator ani, which normally supports the pelvic viscera1. In the present case there may have been additional predisposing factors—the postoperative wound infection, the raised intra-abdominal pressure secondary to paralytic ileus, and the patient's age.

There are three recognized surgical approaches for the repair of hernias occurring in the sacral and perineal region—the anterior (transabdominal), posterior (sacral or perineal) and combined anteroposterior approaches. The posterior approach is associated with less morbidity since the abdominal cavity is not entered, and is thus appropriate for high-risk patients and small hernias. However, the exposure is limited and may not allow examination for tumour recurrence or repair of an intra-abdominal structure injured during the procedure. The anterior approach allows full mobilization of the sac and its contents and facilitates the placement of a sheet of mesh under direct vision. However, it is associated with more postoperative morbidity and should perhaps be reserved for cases in which a laparotomy is required for other reasons5. A combined anteroposterior approach provides the best exposure and allows excision of redundant soft tissue once the hernia is reduced. However, most operators use this approach only in exceptional circumstances5.

Several surgical techniques have been used to repair the hernial defect. If the defect is small, the levator ani can be reapproximated with sutures, although this is usually difficult if the previous cancer resection has been adequate. Occasionally, the bladder or uterus can be sutured to the posterior pelvic wall to eradicate the defect. The pelvic floor can be reconstructed with prosthetic mesh, which is easy to use and can cover a deficiency of any size. If the defect is large, a myocutaneous flap involving gracilis, rectus abdominus or gluteus maximus can also be used. In the previous cases of sacral hernia repair, three groups used mesh and one sutured the uterus to the sacral remnant. No recurrences have been reported.

For reconstruction of the pelvic floor after sacrectomy, Localio et al.6 advocated obliteration of the dead space by tight closure of the gluteus maximus. However, if the resection has been extensive, the residual soft tissue is often insufficient for adequate closure. In these circumstances Santora et al.1 suggest that prosthetic mesh should be used prophylactically to reconstruct the pelvic floor and reduce the likelihood of sacral herniation1.

Symptomatic sacral hernia following sacrectomy is a rare but important complication, and during the initial surgical resection an attempt should be made to close the soft tissues adequately. Like other groups we have found that polypropylene mesh offers a simple, adaptable, and effective method of hernia repair and pelvic floor reconstruction.

References

- 1.Santora T, Kaplan L, Sherk H. Perineal hernia: an undescribed complication following sacrectomy. Orthopedics 1998;21: 203-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehto S, Vakharia M, Fernando T, Mohler D. Polypropylene mesh repair of sacroperineal hernia following sacrectomy with long-term follow up. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 2000;59: 113-15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancrini A, Bellotti C, Santoro A, et al. Postoperative sacrocele: prevention and surgical considerations. G Chir 1997;18: 488-92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chernyi V, Shchepotin I, Klochko P, et al. A method of plastic surgery in postoperative sacro-perineal hernia. Vestin Khir II Grek 1988;140: 88-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.So JB, Palmer M, Shellito P. Postoperative perineal hernia. Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40: 954-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Localio S, Francis K, Rossano P. Abdominosacral resection of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Ann Surg 1967;166: 394-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]