Abstract

There is uncertainty regarding how long the effects of acupuncture treatment persist after a course of treatment. We aimed to determine the trajectory of pain scores over time following acupuncture, using a large individual patient dataset from high quality randomized trials of acupuncture for chronic pain. The available individual patient dataset included 29 trials and 17,922 patients. The chronic pain conditions included musculoskeletal pain (low back, neck and shoulder), osteoarthritis of the knee and headache/migraine. We used meta-analytic techniques to determine the trajectory of post-treatment pain scores. Data on longer-term follow-up were available for 20 trials, including 6376 patients. In trials comparing acupuncture to no acupuncture control (wait-list, usual care, etc), effect sizes diminished by a non-significant 0.011 SD per 3 months (95% CI: −0.014 to 0.037, p = 0.4) after treatment ended. The central estimate suggests that about 90% of the benefit of acupuncture relative to controls would be sustained at 12 months. For trials comparing acupuncture to sham, we observed a reduction in effect size of 0.025 SD per 3 months (95% CI: 0.000 to 0.050, p = 0.050), suggesting about a 50% diminution at 12 months. The effects of a course of acupuncture treatment for patients with chronic pain do not appear to decrease importantly over 12 months. Patients can generally be reassured that treatment effects persist. Studies of the cost-effectiveness of acupuncture should take our findings into account when considering the time horizon of acupuncture effects. Further research should measure longer term outcomes of acupuncture.

INTRODUCTION

In an individual patient data meta-analysis of nearly 18,000 patients on high-quality randomized trials involving patients with chronic pain, the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration reported that acupuncture provided small but statistically significant benefits over sham (placebo) acupuncture, a result that can be distinguished from bias. [35] Moreover a robust and larger effect size was observed when acupuncture was compared to no acupuncture control, with the difference being clinically relevant. [35] The data from each trial entered into the collaboration meta-analysis were the outcomes at the trial’s primary endpoint. For instance, if a trial measured outcome after 12 weeks of treatment and then three months later, but the authors specified the post-treatment follow-up as primary, then it would be the 12 week follow-up used in the meta-analysis.

For approximately two-thirds of the trials in the meta-analysis, the primary endpoint was between one and three months after the end of treatment. The primary endpoint was one year or more after randomization for only two trials. This is problematic in the context of chronic pain. For a patient who has endured chronic pain for a decade or more, the promise of a few months relief, while welcome, is less relevant than the question of whether an intervention provides benefits over the longer term. The duration of acupuncture effects also has clear health economic implications. Whether the benefits of a course of acupuncture treatment are worth its cost depends critically on how long those benefits last.

In this paper, we analyze individual patient data from the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration to determine the time course of acupuncture effects. We sought to take advantage of the fact that many of the eligible trials measured outcome at more than one time point after the end of treatment. By comparing how differences between groups change between two post-treatment time points we aimed to estimate the degree to which the effects of acupuncture persist.

METHODS

Systematic Review

Trials included in these analyses were identified through a systematic literature review that has been previously described [35][36]. The search included trials of acupuncture for chronic pain where allocation concealment was determined unambiguously to be adequate. Eligible pain patients were those with non-specific low back or neck pain, shoulder pain, chronic headache/migraine or osteoarthritis. This search resulted in the identification of 31 trials and individual patient data were obtained from 29 trials. Of these, 18 trials compared acupuncture to no acupuncture controls (Table 1). Control groups included no treatment, wait-list, rescue medication, usual care or protocol-guided care. Patients who were allocated to a wait-list were offered treatment at the end of the trial period. A further 20 trials compared acupuncture to sham acupuncture (Table 2). Nine of these trials had three arms, with patients allocated to acupuncture, no acupuncture or a sham control. We have previously explored the impact of the choice of control group on the effect size of acupuncture, which showed that the more active the control the smaller the apparent effect of acupuncture. [24]

Table 1.

Trials with a no acupuncture control

| Trial Name | Pain Condition | Control patients offered acupuncture treatment (Crossover) | Average Length of Treatment | Time Points after End of Treatment | Included in meta-analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster 2007[10] | Osteoarthritis | No | 3 weeks | Weeks 3, 23 and 49 | Yes |

| Linde 2005[22] | Migraine | At 12 weeks | 8 weeks | Week 4 | No |

| Melchart 2005[25] | Headache | At 12 weeks | 8 weeks | Week 4 | No |

| Thomas 2006[30] | Low Back Pain | No | 12 weeks | Weeks 1, 40 and 92 | Yes |

| Salter 2006[26] | Neck | No | 12 weeks | Week 1 | No |

| Berman 2004[3] | Osteoarthritis | No | 26 weeks | End of treatment | No |

| Cherkin 2001[6] | Low Back Pain | No | 10 weeks | End of treatment and week 42 | Yes |

| Diener 2006[8] | Migraine | No | 6 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 7 and 20 | Yes |

| Scharf 2006[27] | Osteoarthritis | No | 6 weeks | Weeks 7 and 20 | Yes |

| Haake 2007[15] | Low Back Pain | No | 6 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 7 and 20 | Yes |

| Vickers 2004[37] | Headache | No | 6 weeks | Weeks 1 and 40 | Yes |

| Williamson 2007[39] | Osteoarthritis | No | 6 weeks | Weeks 1 and 6 | Yes |

| Witt 2005[40] | Osteoarthritis | At 8 weeks | 8 weeks | End of treatment | No |

| Witt 2006[41] | Neck | At 12 weeks | 12 weeks | All measurements after crossover | No |

| Witt 2006[42] | Osteoarthritis | At 12 weeks | 12 weeks | All measurements after crossover | No |

| Jena 2008[17] | Headache | At 12 weeks | 12 weeks | All measurements after crossover | No |

| Witt ARC 2006[43] | Low Back Pain | At 12 weeks | 12 weeks | All measurements after crossover | No |

| Brinkhaus 2006[4] | Low Back Pain | At 8 weeks | 8 weeks | End of treatment | No |

Table 2.

Sham Controlled Acupuncture Trials

| Trial Name | Pain Condition | Average Length of Treatment | Time Points after End of Treatment | Included in meta-analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlsson 2001[5] | Low Back Pain | 8 weeks | Weeks 4, 12 and 26 | Yes |

| Foster 2007[10] | Osteoarthritis | 3 weeks | Weeks 3, 23 and 49 | Yes |

| Guerra 2004[14] | Shoulder | 8 weeks | Weeks 5 and 18 | Yes |

| Irnich 2001[16] | Neck | 3 weeks | Weeks 1 and 10 | Yes |

| Kennedy 2008[18] | Low Back Pain | 5 weeks | End of treatment and week 7 | Yes |

| Kerr 2003[19] | Low Back Pain | 6 weeks | None | No |

| White 2004[38] | Neck | 4 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 1 through 8 | Yes |

| Linde 2005[22] | Migraine | 8 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 4 and 16 | Yes |

| Melchart 2005[25] | Headache | 8 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 4 and 16 | Yes |

| Berman 2004[3] | Osteoarthritis | 26 weeks | End of treatment | No |

| Kleinhenz 1999[20] | Shoulder | 4 weeks | End of treatment | No |

| Diener 2006[8] | Migraine | 6 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 7 and 20 | Yes |

| Scharf 2006[27] | Osteoarthritis | 6 weeks | Weeks 7 and 20 | Yes |

| Haake 2007[15] | Low Back Pain | 6 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 7 and 20 | Yes |

| Endres 2007[9] | Headache | 6 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 7 and 20 | Yes |

| Vas 2004[32] | Osteoarthritis | 12 weeks | Week 1 | No |

| Vas 2006[34] | Neck | 3 weeks | Weeks 1 and 25 | Yes |

| Vas 2008[33] | Shoulder | 3 weeks | Weeks 1, 10, 23 and 49 | Yes |

| Witt 2005[40] | Osteoarthritis | 8 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 18 and 44 | Yes |

| Brinkhaus 2006[4] | Low Back Pain | 8 weeks | End of treatment and weeks 18 and 44 | Yes |

Outcome

The primary outcome used for this analysis was pain as defined by the study authors. Where multiple criteria were considered in the primary outcome (e.g. a response defined as either a 33% reduction in pain or a 50% reduction in pain medication) or if the primary outcome was inherently categorical, we instead used a continuous measure of pain. To make outcome measurements comparable between different trials, all pain measurements were standardized by dividing by pooled standard deviation and multiplied by 100. Since higher pain scores correspond to lower levels of pain, a positive pain change score corresponds to an improvement (less pain) from baseline, i.e. if a patient had a score of 100 at baseline and 50 after treatment, then they were actually in more pain, not less pain.

Analysis

For a trial to be included in this meta-analysis, the primary outcome must have been measured at least twice after the end of treatment. For trials in which control group patients were later offered acupuncture treatment, data from both acupuncture and control patients were dropped from all time points after the time at which control patients began receiving treatment. Trials were excluded if they had only one measurement after the end of treatment, if all outcome measurements were only during treatment, or if the primary outcome was measured only after control patients began to receive acupuncture. In this analysis, we used all time points in a trial, not just the time point specified as primary by the study authors.

In the primary analysis [35], we did not find evidence that the effects of acupuncture differed by indication. Hence we planned to include all trials together and then examine the data to determine whether there was evidence of a difference in time course by indication, a “lump then split” approach.

To estimate the time course of acupuncture effects, we used the xtgee command in Stata to create a longitudinal model taking into account the correlation between an individual patient’s scores over time. We used the pain intensity score as the dependent variable with baseline score, time and treatment group and an interaction term for group and time as predictors. Since the length of acupuncture treatment varied between trials, time was defined as the number of days since the end of treatment for this model.

To test whether the effects of treatment changed differently over time between the acupuncture and control groups, the analysis was repeated separately for each trial. The coefficients for the interaction term between treatment group and time since end of treatment were saved out along with the standard error of the estimate and entered into a meta-analysis.

As a sensitivity analysis, this model was also used to perform a one-stage meta-analysis for no acupuncture controlled and sham controlled trials separately. Data from all trials were included and the model was also adjusted for trial.

To give a visual representation of how the effects of acupuncture change over time, the results are presented graphically in two ways: as standardized pain scores over time since randomization, and as standardized pain scores over time since the end of treatment. A longitudinal model for the effect of time on pain change score (including cubic splines with knots at the tertiles) was used to predict and graph pain change over time for the acupuncture and control groups separately.

RESULTS

In most trials, patients received 8 – 15 treatments over 10 – 12 weeks. Only one trial had a longer treatment duration, 26 weeks [3]. A subset of studies recorded the number and frequency of sessions actually received by patients on the trial. In the acupuncture arm of trials with a no acupuncture control group, the mean number of treatments was 8 over 8 weeks (N=551). For sham trials, the number and duration of treatment was similar for both the acupuncture and sham arms: a mean of 10 treatments over 6 weeks (N=662).

Acupuncture compared to no acupuncture controls

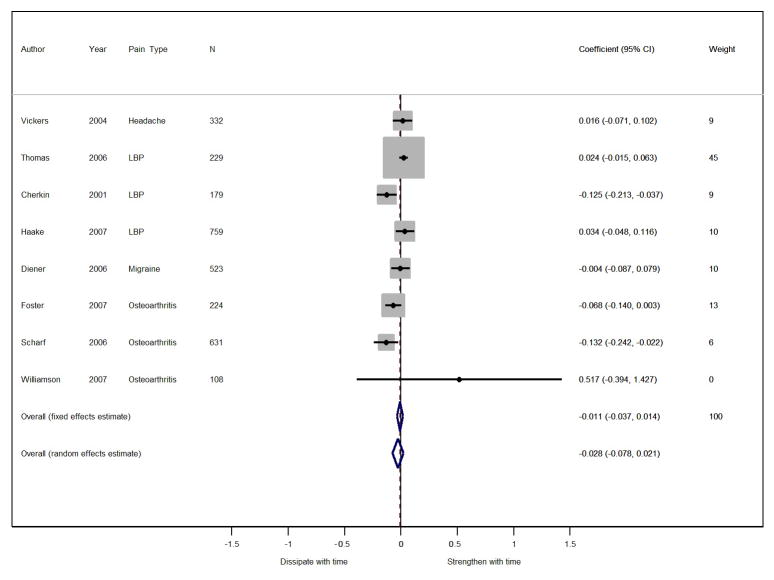

In our analysis of acupuncture versus no acupuncture controls, a total of 8 trials and 2,985 patients were included. The results of the meta-analysis for these 8 trials with no acupuncture controls are shown in Figure 1. Note that in this figure the weights are determined using inverse variance weighting, so for example if a trial had a small confidence interval (very low variance), it had a higher weight than other trials of the same or even larger sizes that had higher variances. Effect size is reported as a post-treatment change in SD per 3 months for the acupuncture trials compared to the no acupuncture controlled trials. The fixed-effects estimate for the between-group comparison of acupuncture versus no acupuncture controls showed a non-significant decrease in the effect size of acupuncture of (0.011 SD per 3 months, 95% C.I. −0.014 to 0.037, p = 0.4) after the end of treatment. As the difference between acupuncture and control has previously been found to be close to 0.5 SD [35], the effect size of 0.011 SD per 3 months is equivalent to about a 9% diminution of treatment effects in the acupuncture versus no acupuncture group at 12 months. There was significant heterogeneity between trials (p=0.006).

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the difference in pain change scores between acupuncture and no acupuncture control groups over time.

A coefficient of 0.01 means that the difference between acupuncture and control increases by 0.01 standard deviations for each 3 months following the end of treatment.

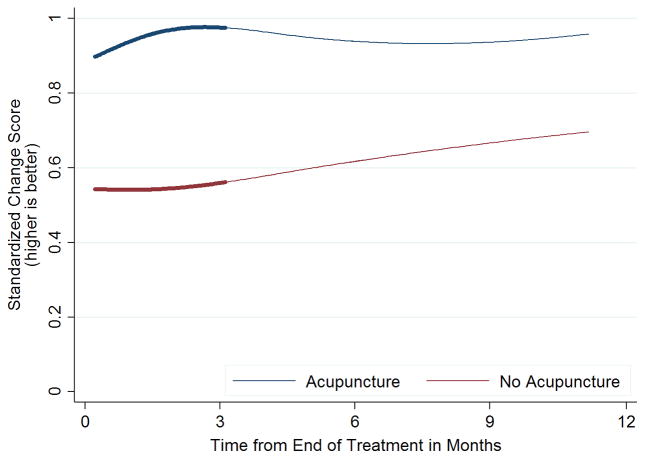

Figure 2 and Supplementary File Figure 1 both show a trend of an increase in the effect of both acupuncture and no acupuncture groups over time, while the difference in the pain change scores between the two groups remains relatively consistent from randomization up to one year after the end of treatment. The effect sizes for the individual arms in these trials that report data beyond six months are presented in Table 3. The increase in overall effects in both arms might be attributable to the smaller effect sizes in the trial at 49 weeks [10] and the larger effect sizes of the trial with the longest follow-up at 92 weeks [30] (Table 3).

Figure 2. Effects of acupuncture and no acupuncture control over time since end of treatment.

Line thickness represents the number of trials contributing data at these time points: the thicker line represents 5–9 trials and the thinner line represents 2–4 trials.

Table 3.

Effect size in SD for trials with follow-up longer than 6 months

| Acupuncture and no acupuncture control arms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Arm | Week 40 | Week 42 | Week 49 | Week 92 |

| Foster 2007[10] | No acupuncture | - | - | 0.60 | |

| Foster 2007[10] | Acupuncture | - | - | 0.55 | |

| Thomas 2006[30] | No acupuncture | 1.09 | - | - | 1.17 |

| Thomas 2006[30] | Acupuncture | 1.30 | - | - | 1.46 |

| Cherkin 2001[6] | No acupuncture | - | 0.91 | - | |

| Cherkin 2001[6] | Acupuncture | - | 0.85 | - | |

| Vickers 2004[37] | No acupuncture | 0.42 | - | - | |

| Vickers 2004[37] | Acupuncture | 0.80 | - | - | |

| Acupuncture and sham acupuncture arms | |||||

| Trial | Arm | Week 23 | Week 25/26 | Week 44 | Week 49 |

| Carlsson 2001[5] | Sham | −0.30 | |||

| Carlsson 2001[5] | Acupuncture | 0.91 | |||

| Foster 2007[10] | Sham | 0.61 | - | - | 0.68 |

| Foster 2007[10] | Acupuncture | 0.56 | - | - | 0.57 |

| Vas 2006[34] | Sham | - | 1.03 | - | - |

| Vas 2006[34] | Acupuncture | - | 1.59 | - | - |

| Vas 2008[33] | Sham | 0.33 | - | - | 0.52 |

| Vas 2008[33] | Acupuncture | 1.02 | - | - | 1.22 |

| Witt 2005[40] | Sham | - | 0.72 | - | |

| Witt 2005[40] | Acupuncture | - | 0.78 | - | |

| Brinkhaus 2006[4] | Sham | - | 0.69 | - | |

| Brinkhaus 2006[4] | Acupuncture | - | 0.76 | - | |

We conducted a sensitivity analysis in which data were entered into a one-stage meta-analysis. In the one-stage approach, the longitudinal model described above was applied to a data set including all trials with a no acupuncture control group. The model incorporated the non-independence between observations on a single patient and between observations on different patients in the same trial. Results for no acupuncture controlled trials were almost identical to the two-stage meta-analysis, with an overall reduction of 0.011 SD per 3 months, (95% CI −0.034, 0.013).

Acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture controls

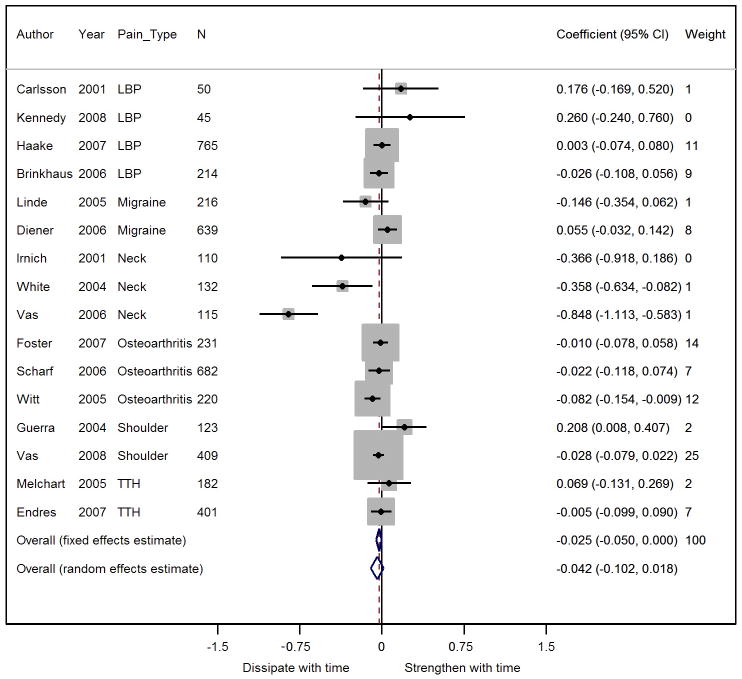

We included a total of 16 trials and 4,534 patients in our analysis for acupuncture versus sham-controlled trials. The results of the meta-analysis for these 16 sham acupuncture controlled trials are shown in Figure 3. Among these trials, we found a significant reduction in pain change scores over time between the sham and acupuncture groups (effect size = −0.025 SD per 3 months, 95% C.I. −0.050 to 0.000, p=0.05) after the end of treatment. Because the difference between acupuncture and sham controls has previously been found to be close to 0.2 SD [35] this reduction would mean about a 50% diminution of effect size for acupuncture compared to sham patients at 12 months. Significant heterogeneity was also seen in sham-controlled trials (p < 0.0001).

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the difference in pain change scores between acupuncture and sham control groups over time.

A coefficient of 0.01 means that the difference between acupuncture and control increases by 0.01 standard deviations for each 3 months following the end of treatment.

For all three neck pain trials [16][34][38] included in this analysis, the effects of acupuncture decreased over time compared to sham (see Figure 3), with two of these trials [34][38] showing a statistically significant decrease. In a sensitivity analysis that excluded neck pain trials, we found that there was a smaller non-significant reduction in how differences in pain between groups changed over time (effect size = −0.014, 95% CI −0.039, 0.011, p = 0.3) after treatment. Moreover there was no longer significant heterogeneity between sham acupuncture-controlled trials (p = 0.2). When excluding these three neck pain trials from the analysis, the diminution of effect in acupuncture patients compared to sham is about 28% at one year, suggesting that most of the effects of acupuncture might persist over time for the non-neck related chronic pain conditions. The Vas trial of acupuncture for shoulder pain [33] had a relatively large weight because outcome was measured three times after the end of treatment, allowing more precise estimates of the time course of treatment. However, excluding this trial had very little effect on the analyses (−0.024 SD per 3 months, 95% CI −0.053, 0.005).

For sham-controlled trials, the one-stage meta-analytic approach found a slightly larger reduction in effect size compared to two-stage meta-analysis (−0.036 SD per 3 months, 95% CI −0.060, −0.012). However, the principal findings were not importantly affected: there was a large reduction in effect for neck pain trials (−0.581 SD per 3 months, −0.736, −0.427) but reductions in effect size for trials on non-neck pain indications were non-significant (−0.021 SD per 3 months, 95% CI −0.046, 0.003).

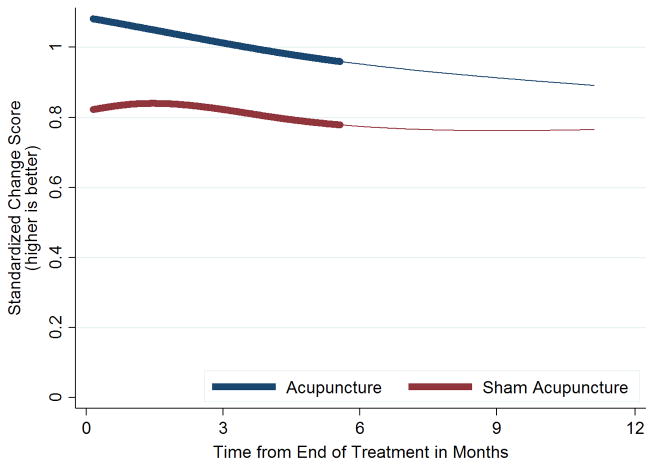

The pain change scores in each group over time after the end of treatment are shown in Figure 4 after randomization are shown in Supplementary File Figure 2. In the latter, the benefits of both acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups appear to be largely sustained over time, with the difference in the pain change scores between the two groups remaining relatively consistent up to one year after randomization. Figure 4 shows a trend of a decrease in the effect of both the acupuncture delivered within a sham controlled trial and the sham acupuncture over time. Among these sham-controlled trials, one trial reported larger effect sizes at six months after the end of treatment [34], and three trials reported data nearer to 12 months after the end of treatment [4][10][40] (Table 3). The fact that the effect sizes in these three trials at one year after treatment are smaller overall than the trial with the large effect sizes reporting data at six months is likely to explain in part the observed decrease in treatment effect in sham controlled trials over time.

Figure 4. Effects of acupuncture and sham acupuncture control over time since end of treatment.

Line thickness represents the number of trials contributing data at these time points: the thicker line represents 10 or more trials and the thinner line represents 2–4 trials.

Post hoc analyses

In light of our findings, we conducted a number of unplanned analyses. To determine whether the estimates of decrease in acupuncture effect relative to sham acupuncture or no acupuncture control are different, we compared the mean difference between acupuncture and each control group. We found no evidence of heterogeneity in how the effects of acupuncture dissipate between sham and no acupuncture-controlled trials when including all trials in the analysis (p=0.5) or when excluding neck pain trials from the analysis (p=0.9).

One reason why we may have failed to find significant reductions in acupuncture effects over time is that the analysis included trials irrespective of whether they reported differences between acupuncture and control. Obviously, a trial that showed no difference between groups cannot show a reduction in acupuncture effects over time. Hence we repeated our analyses excluding trials that concluded no significant effect of acupuncture compared to sham or no acupuncture control. Five no acupuncture controlled trials with 2,059 patients found a significant effect of acupuncture compared to no acupuncture control. Among these trials, there was a non-significant increase in the effects of acupuncture relative to no acupuncture control (0.013 SD per 3 months, 95% CI −0.018, 0.44, p=0.4). There were 7 sham controlled trials with 1,450 patients that found a significant effect of acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture. There was a significant decrease in the effects of acupuncture relative to sham for every 3 months of follow up of 0.049 SD (95% CI −0.086, −0.013, p=0.008) and significant heterogeneity between trials (p<0.0001). Excluding neck pain trials from this sensitivity analysis left 5 trials with 1,203 patients. There was no longer significant heterogeneity (p=0.060) and the decrease in the effect of acupuncture compared to sham was smaller and no longer significant when excluding both neck pain trials and trials that found no effect of acupuncture relative to sham: a decrease of 0.028 SD for every 3 months follow up (95% CI −0.065, 0.009, p = 0.13).

When including all trials that found an effect of acupuncture, there was significant heterogeneity, with the effects of acupuncture decreasing much more rapidly in the sham acupuncture trials than in the no acupuncture controlled trials (p=0.011). However, when excluding the neck pain trials from this analysis, we found a non-significant reduction in the effects of acupuncture over time between the sham controlled and no acupuncture controlled trials that found a significant effect of acupuncture (p=0.097).

To explore these results further, we repeated our analyses separately for neck pain and compared our findings to other pain patient subgroups combined. The estimate of a reduction in neck pain treatment benefit of 0.587 (95% CI 0.406, 0.767) standard deviations per three months is very much higher than the estimate of 0.014 (95% C.I −0.039, 0.011) for comparison conditions (p < 0.0001). On closer inspection of data from each trial, improvements from baseline in the acupuncture group were stable in one trial at 8 weeks post-randomization [38] but decreased by 40 – 50% in two trials with 10 – 25 weeks additional follow-up [16][34].

DISCUSSION

Principal findings

The effects of acupuncture compared to no acupuncture for chronic pain do not appear to decrease importantly over a projected 12 month period. We did not see a statistically significant association with time. The central estimate suggests that about 90% of the benefit of acupuncture relative to controls would be sustained at 12 months, or when using the upper bound of the confidence interval, about 70% of the benefit of acupuncture relative to controls would be sustained at 12 months.

The results for acupuncture versus sham were similar after exclusion of studies on neck pain. We did see clear evidence that the effects of acupuncture versus sham on neck pain do diminish over time. When excluding neck pain trials from the analysis to reduce heterogeneity, the diminution of effect in acupuncture patients compared to sham was about 30% at one year, suggesting that much of the effects of acupuncture persist over time for the non-neck related chronic pain conditions. This might be explained in part by the shorter courses of treatment provided in the neck pain trials [16,34,38], which were in the range of 3 to 4 weeks, in contrast to the more commonly provided courses lasting 6 to 8 weeks or longer for the other conditions (see Table 2).

Strengths and limitations

The key strength of this study is that we have used a meta-analysis drawing on an individual patient data from high quality randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for chronic pain, which found that acupuncture was superior to both sham and no acupuncture controls for each pain condition. [35] Using this large dataset of nearly 18,000 patients, we have been able to explore sub-groups with a precision not possible when using only summary trial data, as would be the case when using conventional meta-analytic methods. A key limitation was that not all trials in the dataset provided data at more than one post-treatment follow-up. We only have data from eight of the twenty trials that followed patients for 40 weeks or more. One trial provided follow-up at two years after randomization. [22] We do believe it is reasonable to draw conclusions about the time course of acupuncture effects over a one-year period. First, the data that we do have from trials with longer term follow-up does indeed suggest persistence of effects, incidentally a characteristic that may not be unique to acupuncture. Second, we did not see any difference on how treatment benefit changed over time comparing trials with longer versus shorter follow-up, which is why we used data from all trials to estimate the effects of time on treatment. It would be incorrect to conclude that “no important diminution of effect at 12 months” means “effects persist well beyond 12 months”.

Relationship to the wider literature

Our conclusions as to the time course over which acupuncture appears to provide benefits differ to some extent from data reported in a number of prior systematic reviews of acupuncture for chronic pain based on summary. [1][2][7][11][13][12][23][21][28][29][31] The critical difference between the current paper and prior reviews is that the latter reviews did not directly evaluate the time course of acupuncture effects. When a prior review reports that results were significant at an early time point, but not at a later time point, this cannot be taken as evidence that results changed over time. There are several reasons why significance may change even if underlying effects do not. The most obvious is if the number of patients changes over time due to drop out. For instance, a trial with 150 patients per group and a 0.25 standard deviation difference between groups at post-treatment would be statistically significant (p=0.031). If results were identical at a six-month follow-up, but 25% of patients dropped out, the p value would be 0.063. Alternatively, if there was no drop out and no changes in mean pain scores, but longer follow-up was associated with a 25% increase in standard deviation, perhaps associated with greater variability of pain over time, the p value would again be non-significant (p=0.084). In both cases, the effects of treatment persist, and an analysis directly testing trends over time would confirm this finding; taking the approach of the conventional reviews and indirectly assessing change over time by separate inference at different timepoints would lead to incorrect conclusions regarding the time course of underlying effects. We are the first systematic review to directly analyze change over time using appropriate methods for longitudinal data.

Differences between our results and the previously published systematic reviews can be illustrated by taking as an example the review by Furlan et al [12] who found that, “acupuncture did not significantly differ from placebo in improving pain intensity scores” for low back and neck pain. In our meta-analysis, we used different inclusion criteria to select trials for review, which included the multiple pain conditions of headache/migraine, osteoarthritis and low back and neck pain, whereas Furlan only included low back and neck pain. Our more strict inclusion criteria required evidence of unambiguous allocation concealment, leading to our inclusion of only higher quality trials, which are less likely to be susceptible to bias. The critical difference however between the analysis we present here and the analyses of Furlan et al. is that they did not directly address the time course of acupuncture effects. Their analyses were limited to those trials that measured similar outcomes during approximately the same time periods. We obtained patient data from all eligible trials and performed an individual patient data meta-analysis within which we were able to standardize and compare multiple types of outcome. Since we had individual patient data, we were able to incorporate outcomes measured at all time points from all trials into one analysis, rather than drawing conclusions from multiple separate analyses and we therefore conducted an analysis that directly addressed the question at hand.

Implications for research and practice

The major clinical implication of our findings is that we can reassure chronic pain patients considering acupuncture that any treatment benefit does persist after the end of treatment. This is naturally also a consideration for other clinicians who may refer patients for acupuncture. A concern for such clinicians and their patients is that they may go through the time, trouble and expense of a course of acupuncture treatment, but then regress to having the same amount of pain shortly after treatment ends. This cannot be assumed, given the evidence that the effects of acupuncture for chronic pain persist for at least a year. A possible exception is neck pain, as we saw some evidence that differences between acupuncture and sham decrease over time for this condition.

Our findings also have implications on cost-effectiveness studies that use utility measures. Such studies calculate benefit, in terms of increase in quality adjusted life years (QALYs) associated with an intervention, and divide by the increase in cost associated with that intervention. Increase in QALYs depends on a “time horizon” for treatment effectiveness. In many cost-effectiveness studies on acupuncture, this time horizon is given as the length of follow-up, effectively assuming that the benefits of acupuncture disappear completely the moment that a patient completes their final questionnaire or follow-up assessment. Changing the time horizon dramatically impacts cost-effectiveness. In the case of a trial with the final follow-up at three months, but using a time horizon of 12 months (a minimum based on our data) rather than a time horizon of 3 months, would reduce the cost per QALY by 75%.

In terms of future prospective research, it is clear that further studies should continue to measure outcomes beyond the end of acupuncture treatment, at least at 12 months follow-up and, ideally, beyond. In one Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration study [37], the average duration of chronic pain in the study cohort was over 20 years. It surely behoves the research community to adequately fund studies to assess long-term outcomes in patients with chronic pain. Given the discrepant results for chronic neck pain, future studies could focus specifically on the time course of acupuncture for this type of pain. Moreover there is a case for exploring the biological plausibility of physiological changes in sub-studies embedded within clinical trials in order to provide a mechanistic explanation of the longer terms benefits associated with acupuncture. It is also plausible that the sustained effects of acupuncture may be explained by, as yet unspecified and unmeasured, treatment mediating factors.

CONCLUSION

With the possible exception of neck pain, the effects of acupuncture compared to no acupuncture for chronic pain do not appear to decrease importantly over 12 months. Patients can generally be reassured that treatment effects are likely to persist. Cost-effectiveness studies should take our findings into account when considering the time horizon of acupuncture treatment. Further research should measure long-term outcome of acupuncture for patients with chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

The vertical line represents the mean length of acupuncture treatment. Line thickness represents the number of trials contributing data at these time points: the thicker line represents 5–9 trials and the thinner line represents 2–4 trials.

The vertical line represents mean length of acupuncture treatment. Line thickness represents the number of trials contributing data at these time points: the thicker line represents 10 or more trials and the thinner line represents 2–4 trials.

Acknowledgments

The study has been supported by the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration, which includes physicians, clinical trialists, biostatisticians, practicing acupuncturists and others. The collaborators within the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration are:

• Mac Beckner, MIS, Information Technology and Data Management Center, Samueli Institute, Alexandria, Virginia;

• Brian Berman, MD, University of Maryland School of Medicine and Center for Integrative Medicine, College Park; Maryland;

• Benno Brinkhaus, MD, Institute for Social Medicine, Epidemiology and Health Economics, Charité University Medical Center, Berlin, Germany;

• Remy Coeytaux, MD, PhD, Department of Community and Family Medicine, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina;

• Angel M. Cronin, MS, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts;

• Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, PhD, Department of Neurology, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany;

• Heinz G. Endres, MD, Ruhr–University Bochum, Bochum, Germany;

• Nadine Foster, DPhil, BSc(Hons), Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre, Research Institute of Primary Care and Health Sciences, Keele University, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, England;

• Juan Antonio Guerra de Hoyos, MD, Andalusian Integral Plan for Pain Management, and Andalusian Health Service Project for Improving Primary Care Research, Sevilla, Spain;

• Michael Haake, MD, PhD, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, SLK Hospitals, Heilbronn, Germany;

• Dominik Irnich, MD, Interdisciplinary Pain Centre, University of Munich, Munich, Germany;

• Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Samueli Institute, Alexandria, Virginia;

• Kai Kronfeld, PhD, Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Trials (IZKS Mainz), University Medical Centre Mainz, Mainz, Germany;

• Lixing Lao, PhD, University of Maryland and Center for Integrative Medicine, College Park, Maryland;

• George Lewith, MD, FRCP, Complementary and Integrated Medicine Research Unit, Southampton Medical School, Southampton, England;

• Klaus Linde, MD, Institute of General Practice, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany;

• Hugh MacPherson, PhD, Complementary Medicine Evaluation Group, University of York, York, England;

• Eric Manheimer, MS, Center for Integrative Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, College Park, Maryland;

• Alexandra Maschino, MPH, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland;

• Dieter Melchart, MD, PhD, Centre for Complementary Medicine Research (Znf), Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany;

• Albrecht Molsberger, MD, PhD, German Acupuncture Research Group, Duesseldorf, Germany;

• Karen J. Sherman, PhD, MPH, Group Health Research Institute, Seattle, Washington;

• Hans Trampisch, PhD, Department of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, Ruhr–University Bochum, Germany;

• Jorge Vas, MD, PhD, Pain Treatment Unit, Dos Hermanas Primary Care Health Center (Andalusia Public Health System), Dos Hermanas, Spain;

• Andrew J. Vickers (collaboration chair), DPhil, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York;

• Peter White, PhD, School of Health Sciences, University of Southampton, England;

• Lyn Williamson, MD, MA (Oxon), MRCGP, FRCP, Great Western Hospital, Swindon, and Oxford University, Oxford, England;

• Stefan N. Willich, MD, MPH, MBA, Institute for Social Medicine, Epidemiology, and Health Economics, Charité University Medical Center, Berlin, Germany;

• Claudia M. Witt, MD, MBA, Institute for Complementary and Integrative Medicine, University Zurich and University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Funding statement

The Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration is funded by an R21 (AT004189I and an R01 (AT006794) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to Dr Vickers) and by a grant from the Samueli Institute. Dr MacPherson’s work on this project was funded in part by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0707-10186). Professor Lewith’s contribution has been supported in part by the School for Primary Care Research, which is part of the NIHR. Dr. Witt’s work has been supported by the Carstens Foundation within the grant for the Chair for Complementary Medicine Research. Professor Foster has been supported by an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-011-015). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NCCAM, NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health in England. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Members of the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration are listed in the acknowledgements at the end of the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Bennell KL, Buchbinder R, Hinman RS. Physical therapies in the management of osteoarthritis: current state of the evidence. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2015;27:304–311. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennell KL, Hall M, Hinman RS. Osteoarthritis year in review 2015: rehabilitation and outcomes. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2016;24:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman BM, Lao L, Langenberg P, Lee WL, Gilpin AMK, Hochberg MC. Effectiveness of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:901–910. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinkhaus B, Witt CM, Jena S, Linde K, Streng A, Wagenpfeil S, Irnich D, Walther HU, Melchart D, Willich SN. Acupuncture in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:450–457. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlsson CP, Sjölund BH. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study with long-term follow-up. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:296–305. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherkin DC, Eisenberg D, Sherman KJ, Barlow W, Kaptchuk TJ, Street J, Deyo RA. Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1081–1088. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.8.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, Fu R, Dana T, Kraegel P, Griffin J, Grusing S, Brodt E. Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. [Accessed 7 Aug 2016]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350276/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diener HC, Kronfeld K, Boewing G, Lungenhausen M, Maier C, Molsberger A, Tegenthoff M, Trampisch HJ, Zenz M, Meinert R. Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:310–316. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endres HG, Böwing G, Diener H-C, Lange S, Maier C, Molsberger A, Zenz M, Vickers AJ, Tegenthoff M. Acupuncture for tension-type headache: a multicentre, sham-controlled, patient-and observer-blinded, randomised trial. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:306–314. doi: 10.1007/s10194-007-0416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster NE, Thomas E, Barlas P, Hill JC, Young J, Mason E, Hay EM. Acupuncture as an adjunct to exercise based physiotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39280.509803.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin D, Tsukayama H, Lao L, Koes B, Berman B. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration. Spine. 2005;30(8):944–963. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158941.21571.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, Gross A, Tulder MV, Santaguida L, Cherkin D, Gagnier J, Ammendolia C, Ansari MT, Ostermann T, Dryden T, Doucette S, Skidmore B, Daniel R, Tsouros S, Weeks L, Galipeau J. Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Back Pain II. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, Gross A, Van Tulder M, Santaguida L, Gagnier J, Ammendolia C, Dryden T, Doucette S, Skidmore B, Daniel R, Ostermann T, Tsouros S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of selected complementary and alternative medicine for neck and low-back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:953139. doi: 10.1155/2012/953139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerra de Hoyos J, Andrés Martín M, Bassas y Baena de Leon E, Abdalla M, Molina López T, Verdugo Morilla F, González Moreno M. Randomised trial of long term effect of acupuncture for shoulder pain. Pain. 2004;112:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, Basler HD, Schafer H, Maier C, Endres HG, Trampisch HJ, Molsberger A. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1892–1898. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irnich D, Behrens N, Molzen H, Konig A, Gleditsch J, Krauss M, Natalis M, Senn E, Beyer A, Schops P. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. BMJ. 2001;322:1574–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jena S, Witt CM, Brinkhaus B, Wegscheider K, Willich SN. Acupuncture in patients with headache. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:969–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy S, Baxter GD, Kerr DP, Bradbury I, Park J, McDonough SM. Acupuncture for acute non-specific low back pain: a pilot randomised non-penetrating sham controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2008;16:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr DP, Walsh DM, Baxter D. Acupuncture in the management of chronic low back pain: a blinded randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:364–370. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinhenz J, Streitberger K, Windeler J, Gussbacher A, Mavridis G, Martin E. Randomised clinical trial comparing the effects of acupuncture and a newly designed placebo needle in rotator cuff tendinitis. Pain. 1999;83:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam M, Galvin R, Curry P. Effectiveness of Acupuncture for Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Spine. 2013;38:2124–2138. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000435025.65564.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linde K, Streng A, Jurgens S, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes MG, Weidenhammer W, Willich SN, Melchart D. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2118–2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Skinner M, McDonough S, Mabire L, Baxter GD. Acupuncture for Low Back Pain: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:1–18. doi: 10.1155/2015/328196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacPherson H, Vertosick E, Lewith G, Linde K, Sherman KJ, Witt CM, Vickers AJ on behalf of the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration. Influence of Control Group on Effect Size in Trials of Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: A Secondary Analysis of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melchart D, Streng A, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes M, Hummelsberger J, Irnich D, Weidenhammer W, Willich SN, Linde K. Acupuncture in patients with tension-type headache: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331:376–382. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38512.405440.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salter GC, Roman M, Bland MJ, MacPherson H. Acupuncture for chronic neck pain: a pilot for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scharf H, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, Witte S, Kramer J, Maier C, Trampisch H, Victor N. Acupuncture and Knee Osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:12–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shengelia R, Parker SJ, Ballin M, George T, Reid MC. Complementary Therapies for Osteoarthritis: Are They Effective? Pain Management Nursing. 2013;14:e274–e288. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas D-A, Maslin B, Legler A, Springer E, Asgerally A, Vadivelu N. Role of Alternative Therapies for Chronic Pain Syndromes. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20:29. doi: 10.1007/s11916-016-0562-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Thorpe L, Brazier J, Fitter M, Campbell MJ, Roman M, Walters SJ, Nicholl J. Randomised controlled trial of a short course of traditional acupuncture compared with usual care for persistent non-specific low back pain. BMJ. 2006;333:623–626. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38878.907361.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trinh K, Graham N, Irnich D, Cameron ID, Forget M. The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. [Accessed 7 Aug 2016]. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Available: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD004870.pub4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vas J, Mendez C, Perea-Milla E, Vega E, Panadero MD, Leon JM, Borge MA, Gaspar O, Sanchez-Rodriguez F, Aguilar I, Jurado R. Acupuncture as a complementary therapy to the pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2004;329:1216. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38238.601447.3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vas J, Ortega C, Olmo V, Perez-Fernandez F, Hernandez L, Medina I, Seminario JM, Herrera A, Luna F, Perea-Milla E, Mendez C, Madrazo F, Jimenez C, Ruiz MA, Aguilar I. Single-point acupuncture and physiotherapy for the treatment of painful shoulder: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:887–893. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Méndez C, Sánchez Navarro C, León Rubio JM, Brioso M, García Obrero I. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: a randomised controlled study. Pain. 2006;126:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, Sherman KJ, Witt CM, Linde K. Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1444–1453. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Victor N, Sherman KJ, Witt C, Linde K. Individual patient data meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic pain: protocol of the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration. Trials. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vickers AJ, Rees RW, Zollman CE, McCarney R, Smith CM, Ellis N, Fisher P, Van Haselen R. Acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care: large, pragmatic, randomised trial. BMJ. 2004;328:744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38029.421863.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White P, Lewith G, Prescott P, Conway J. Acupuncture versus placebo for the treatment of chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:911–919. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williamson L, Wyatt MR, Yein K, Melton JT. Severe knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial of acupuncture, physiotherapy (supervised exercise) and standard management for patients awaiting knee replacement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1445–1449. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witt C, Brinkhaus B, Jena S, Linde K, Streng A, Wagenpfeil S, Hummelsberger J, Walther HU, Melchart D, Willich SN. Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:136–143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, Liecker B, Wegscheider K, Willich SN. Acupuncture for patients with chronic neck pain. Pain. 2006;125:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, Liecker B, Wegscheider K, Willich SN. Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip: a randomized, controlled trial with an additional nonrandomized arm. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3485–3493. doi: 10.1002/art.22154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witt CM, Jena S, Selim D, Brinkhaus B, Reinhold T, Wruck K, Liecker B, Linde K, Wegscheider K, Willich SN. Pragmatic randomized trial evaluating the clinical and economic effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:487–496. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The vertical line represents the mean length of acupuncture treatment. Line thickness represents the number of trials contributing data at these time points: the thicker line represents 5–9 trials and the thinner line represents 2–4 trials.

The vertical line represents mean length of acupuncture treatment. Line thickness represents the number of trials contributing data at these time points: the thicker line represents 10 or more trials and the thinner line represents 2–4 trials.