Abstract

Background

Research on susceptibility to alcohol use disorder within the Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) population has begun to expand examination of putative moderators and mediators in order to develop effective treatments. Specific dysregulated emotions have been separately associated with ADHD and with alcohol use difficulties. The current study is the first to conjointly study these variables by testing anger-irritability as a mediator of ADHD risk for adolescent alcohol use.

Methods

Frequency of binge drinking, drunkenness, and alcohol problems were examined for 142 children with ADHD followed into adolescence and compared to 100 demographically similar youth without ADHD. Parent-rated anger-irritability was tested as a mediator. Behavioral and cognitive coping skills, which are key clinical treatment targets, were studied as moderators of these associations.

Results

Childhood ADHD was positively associated with anger-irritability and the drinking outcomes in adolescence. Anger-irritability mediated the association between ADHD and alcohol use problems, but not binge drinking or drunkenness. Behavioral and cognitive, but not avoidant, coping played a moderating role, but only of the association between childhood ADHD and anger-irritability.

Conclusions

Active coping strategies by adolescents with ADHD may reduce the vulnerability to alcohol problems through a reduction of negative emotions. Future research on additional mediators and treatments that target these skills is encouraged.

Keywords: ADHD, emotional dysregulation, alcohol abuse, adolescence

Introduction

A sizeable body of research, conducted over the past 20 plus years, has increasingly shown that a diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in childhood significantly increases the risk for later substance use and substance use disorders (for review see Lee, Humphreys, Flory, Liu, & Glass, 2011). However, research specifically on the association between childhood ADHD and adolescent alcohol use has found mixed results (Biederman et al., 1997; Barkley, Fischer, Edelbrock, & Smallish, 1990; Molina & Pelham, 2003; Molina et al., 2013; Sibley et al., 2014). Lee and colleagues’ meta-analytic review (Lee et al., 2011) found that children with ADHD were significantly more likely than controls to develop an alcohol use disorder, but they were not different in rates of alcohol use. To better understand this elusive connection, studies are needed that examine the possible moderators and mediators of the relation between childhood ADHD and adolescent alcohol use (Molina & Pelham, 2014). The current study examined two individual difference variables that have been investigated for their role in ADHD-related impairment and separately for their associations with adolescent alcohol use: anger-irritability and coping skills. These variables have substantial clinical relevance but they have yet to be studied for their joint contribution to alcohol use by adolescents with ADHD histories.

Results of a recent comprehensive review on irritability (Vidal-Ribas, Brotman, Valdivieso, Leibenluft, & Stringaris, 2016) indicated that irritability is a relatively stable dimension and associated with later psychological and functional impairment. A rapidly growing area of interest in ADHD research is the tendency for individuals with the disorder to have chronic difficulty with angry, irritable behavior and mood (Barkley & Fischer, 2010; Karalunas, Fair, Musser, Aykes, Iyer, & Nigg, 2014; Martel, 2009; Sobanski et al., 2010). For example, Karalunas and colleagues (2014) identified a potentially neurobiologically distinct and stable subtype of ADHD characterized by extreme levels of negative emotionality. This tendency of some children with ADHD to be often irritable and easily angered is partially reflected in the common ADHD comorbidity of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD; Biederman, Newcorn, & Sprich, 1991). Importantly, the symptoms of ODD include an anger-irritability subset (loses temper, touchy or easily annoyed, angry or resentful) that are thought to represent an identifiable phenotype (Drabick & Gadow, 2012; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009) and psychometric work has established their independence from the remaining ODD symptoms (Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2010; Ezpeleta, Granero, de la Osa, Penelo, & Domènech, 2012). These ODD items (Fernández de la Cruz et al 2015; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009) or expanded, similar assessments (such as ‘emotional impulsiveness’, Barkley & Fischer, 2010), although correlated with ADHD and the remaining ODD symptoms, have shown unique prognostic utility for individuals with ADHD. For example, ‘emotional impulsiveness,’ which included quick to anger, easily frustrated, and temper loss among other items, predicted seven major life domains and overall impairment in early adulthood (Barkley et al., 2010).

Difficulties in anger-irritability may help to explain why some children with ADHD are prone to alcohol use in adolescence. Among community samples of older adolescents, variables tapping various definitions of negative emotionality have been repeatedly associated with alcohol use and alcohol use problems (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000; Kaiser, Milich, Lynam, & Charnigo, 2012; Wray, Simons, Dvorak, & Gaher, 2012). Anger has been repeatedly associated with adolescent alcohol use (Eftekhari, Turner, & Larimer, 2004; Wills, Walker, Mendoza, & Ainette, 2006) leading Pardini, Lochman, and Wells (2004) to suggest that among the components of negative emotionality, anger may be most ‘strongly related to the use of alcohol and illicit drugs’. It has been suggested that high rates of expressed anger may reflect a general pattern of poor inhibitory control over negative emotion (Eftekhari et al., 2004) and, central to the current examination of anger-irritability, negative emotions that are impulsively expressed have been associated with alcohol problems in adolescence and young adulthood (for review see: Stautz & Cooper, 2013). To our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined the degree to which anger-irritability is associated with alcohol use among individuals with ADHD.

Relatedly, the utilization of ineffective or maladaptive coping strategies for the management of negative emotions has been associated with adolescent alcohol use (Wills et al., 2006). Coping can be understood as the cognitive and behavioral strategies used to manage the emotional sequela of internal and external stressors (Lazarus, 1993). Previous studies conducted in college samples have shown that coping skills influence the association between anger and alcohol use (Pardini et al., 2004; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004). For example, adaptive coping strategies such as problem solving and behavioral coping have been shown to dampen the association between avoidant and/or angry coping and alcohol use for nonclinical samples of adolescents and young adults (Wills, 2001; Hussong & Chassin, 2004).

Compared to peers without ADHD, children (Babb, Levine, & Arseneault, 2010; Ghanizadeh & Haghighi, 2010), adolescents (Hampel, Manhal, Roos, & Desman, 2008; Molina, Marshal, Pelham, & Wirth, 2005), and adults (Young, 2005; Ramirez et al., 1997) with ADHD have been shown to more often utilize maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance, rumination, and aggression (Hampel et al., 2008). In addition, individuals with ADHD have been shown to utilize fewer adaptive coping strategies (Babb et al., 2010; Ghanizadeh & Haghighi, 2010; Molina et al., 2005) such as problem solving and perspective taking. Taken together, the overuse of maladaptive strategies and the underuse of adaptive coping strategies suggest that the cognitive and behavioral techniques employed by this population to manage negative emotional states may often be ineffective. This, we hypothesize, exacerbates risk for adolescent alcohol use.

We previously reported significant associations between a childhood diagnosis of ADHD, frequency of binge drinking and drunkenness, and an adolescent-appropriate dimensional measure of alcohol problems (Marshal, Molina, & Pelham, 2003; Molina & Pelham, 2003). This study tested anger-irritability as a mediator of these associations. We also tested the hypothesis that adaptive coping skills would serve as a moderator by lowering the strength of associations among ADHD, anger-irritability, and the alcohol variables. (The reverse was expected for maladaptive coping.) To our knowledge, this was the first study to test these associations. Findings may have important clinical implications for the management of alcohol use disorder risk for individuals with ADHD.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 142 adolescents with childhood ADHD and 100 demographically similar adolescents without ADHD. Individuals with ADHD were first diagnosed in childhood and subsequently recruited to participate in this follow-up study. Those without ADHD were newly recruited as adolescents. Mean age for the total sample was 15.2 years (SD = 1.4, range = 13–18 years). Most participants were Caucasian (87%), 10% were African American, and 3% had other racial or ethnic backgrounds. Most were male (94%), and most lived in two-parent households (71%). All mothers and 96% of fathers had graduated from high school or received their high school equivalency degree; 43% of mothers and 46% of fathers had graduated from college. Median family income was $48,000. By study design, there were no statistically significant group differences in adolescent age, gender, ethnicity, parent education, and proportion of single-parent households.

Adolescents with childhood ADHD

Participants with ADHD were recruited as adolescents from the ADD Program records at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, for services they received as children between 1987 and 1995. These children had received a DSM–III–R or DSM–IV diagnosis of ADHD. In childhood, parents and teachers completed a packet of intake measures that included the Disruptive Behavior Disorders scale (DBD; Pelham, Evans, Gnagy, & Greenslade, 1992), the IOWA/Abbreviated Conners (Goyette, Conners, & Ulrich, 1978; Loney & Milich, 1982), and the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham scale (SNAP; Atkins, Pelham, & Licht, 1985), which are norm-referenced, standardized paper-and-pencil measures of DSM–III–R and DSM–IV ADHD symptoms and additional behaviors. In addition, a semi-structured diagnostic interview was conducted with parents of the children by clinicians to confirm presence of DSM–III–R or DSM–IV ADHD symptoms, assess comorbid problems, and rule out alternative diagnoses. Children were excluded from this follow-up study if their IQ was less than 80; if they had a seizure disorder or other neurological problems; or if they had a history of pervasive developmental, psychotic, sexual, or organic mental disorders.

Adolescents who participated in the current study were between 5 and 17 years old at their childhood assessment, although most (88.7% of 142) were between 5 and 12 years old. An average of 5.26 years elapsed between the childhood and adolescent follow-up assessments (SD = 2.22 years). Of the contacted eligible adolescents, 56.5% participated in the follow-up study between 1994 and 2000. Despite the modest rate of participation, comparisons between nonparticipants and 111 of the participants with complete childhood data indicated no statistically significant differences in ADHD/ODD/CD symptoms or IQ/achievement scores (all Cohen’s ds < .20).

Adolescents without childhood ADHD

Participants without ADHD were recruited as adolescents from the Greater Pittsburgh area using newspaper advertisements (54%), flyers in schools attended by probands (9%), advertisements in the university hospital voice mail system or newsletter that reaches a large network of hospital staff (26%), or other (e.g., word of mouth, 11%). A phone screening questionnaire was used with parents to ascertain demographic characteristics and to rule out history of diagnosis and treatment for ADHD or symptoms of ADHD consistent with a DSM–III–R diagnosis. Participants were also ruled out for ADHD diagnosis after direct interview based on parent and teacher DBD reports and by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC 2.3; Shaffer et al., 1996) completed by the adolescents’ mothers. (Other psychopathologies were allowed to avoid recruiting a ‘supernormal’ comparison group.) Controls were selected to ensure similarity between groups on age, gender, race, parent education, and one- vs. two-parent households. The same exclusionary criteria used with the ADHD group was also applied to the nonADHD group and participants received a brief standardized intellectual assessment (Wechsler, 1991) as part of the direct interview. Elsewhere we report non-significant group differences in anxiety and mood disorder yet more ODD/CD in the ADHD than nonADHD group (Bagwell, Molina, Kashdan, Pelham, & Hoza, 2006).

Procedure

For this study, adolescents and their parents participated in a one-time office-based interview. Following collection of informed consent, participants were interviewed separately. Paper-and-pencil questions and interview questions were read aloud to adolescents, who followed along on their own copy of most measures. Adolescents were read the items due to initial concerns about reading and attention difficulties. Participants circled their answers on their own paper and pencil copy which was handed back to the research assistant in an envelope to minimize participant reactivity. Confidentiality was supported with a Certificate of Confidentiality from the Department of Health and Human Services with certain exceptions (e.g., suicidality, child abuse), and the protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board. Additional details regarding recruitment and procedures are in Molina and Pelham (2003).

Measures

All measures described were collected at the adolescent interview (follow-up for the probands; one-time interview for the controls).

Alcohol use was measured as part of a larger questionnaire about lifetime and current substance use (SUQ; Molina & Pelham, 2003). Participants reported their past six-month frequency of drunkenness (‘…how often have you gotten drunk or very, very high on alcohol?’) and binge drinking (‘…how often did you drink five or more drinks when you were drinking?’). Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 9 (more than twice a week).

Adolescent report of alcohol use disorder symptoms was assessed using a highly structured interview version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R (SCID; Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbon, 1987) that we modeled after work by Martin and colleagues (Martin, Kaczynski, Maisto, Bukstein, & Moss, 1995; Martin, Pollock, Lynch, & Bukstein, 2000) to include DSM–IV substance use disorder criteria and symptoms appropriate for adolescents. Each symptom score ranged from 0 (never experienced the problem) to 2 (experienced the problem to a clinically significant degree). A summed symptom (problem) score was used as a developmentally sensitive index of emerging alcohol problems in adolescence.

Anger-irritability was assessed using the DBD. Similar to previous studies (Fernández de la Cruz et al 2015; Drabick & Gadow, 2012), we used the following ODD items: loses temper, touchy or easily annoyed, angry or resentful (α = .87). Mothers (father report if mother was missing) rated adolescents on the preceding items using a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). Item responses were averaged to create our measure of anger-irritability (range = 0.0–2.25; M = .92, SD = .67).

Behavioral, cognitive, and avoidant coping skills (Wills, 1986) were assessed using parent report of 13 items such as ‘My child gets information that is necessary to deal with the problem’ (behavioral coping scale, 6 items, α = .78), ‘My child reminds himself/herself that it could be worse’ (cognitive coping scale, 4 items, α = .76), and ‘Waits and hopes things will get better’ (avoidant coping scale, 3 items, α = .66). Items were rated on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (usually) and described ‘what your son or daughter does when he/she has a problem.’ Although most research on adolescent coping uses self-report, we used parent report because of the well-established tendency for children and adolescents with ADHD to underestimate symptoms and impairment (Hoza, Pelham, Dobbs, Owens, & Pillow, 2002; Sibley et al., 2012).

Data Analysis

Mediation analyses

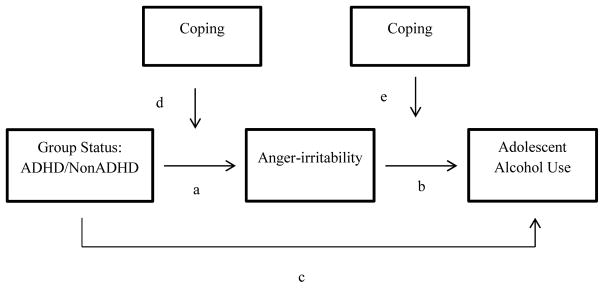

We used the causal steps guidelines described by Baron and Kenny (1986) and expanded by others (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993) to examine anger-irritability as a mediator of the association between childhood ADHD and adolescent drinking. Three conditions are required for mediation. First, prior to controlling for the variance accounted for by the mediator (anger-irritability), the independent (ADHD) and dependent variables (frequency of binge drinking, frequency of drunkenness, alcohol problems) should be related (c). Second there should be relations between the mediator and dependent variables (b) and between the independent variable and mediator (a). These pathways are shown in Figure 1. We used multiple regression analyses to test these associations and employed the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2014) to specifically test the mediational pathway for each drinking variable. Mediated effects were calculated by multiplying the unstandardized beta coefficients (ab; see Figure 1) and tested for significance by estimating bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals through the use of bootstrapping procedures. All predictors were mean centered. Adolescent age was included as a covariate in all models based on prior findings that age, but not IQ, parent education, or proportion of single parent families, co-varied with adolescent substance use (Molina et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Moderated Mediation Model

Moderated mediation was tested in two steps. First, within the regression models described above, we tested the hypothesis that coping (behavioral, cognitive, and avoidant) moderated the a and b paths (associations) of the mediation model (d and e in Figure 1). Secondly, when coping significantly interacted with a predictor (ADHD or anger-irritability), we examined the direction and significance of the associations (simple slopes) at high and low levels of coping, calculated at 1 SD above (high) and below (low) the sample mean.

Results

Descriptive statistics

A comprehensive list of demographic characteristics of this sample has been previously published (Molina & Pelham, 2003). About half (46.0% nonADHD, 52.1% ADHD, ns) of the adolescents had used alcohol previously (Molina & Pelham, 2003). However, the ADHD group drank more heavily (more frequently drunk and more frequent binge drinking) than the nonADHD group (Molina & Pelham, 2003; Marshal, Molina, & Pelham, 2003) and had higher alcohol problem scores compared to the nonADHD group (Molina & Pelham, 2003).

Anger-irritability was higher in the ADHD versus nonADHD group and the effect size was large which supported path a. Of the adolescents in the ADHD group, 42% received average ratings above 2.0, corresponding to ratings of ‘pretty much’ (2) or ‘very much’ (3), compared to 4% for the nonADHD group. As previously reported (Molina et al., 2005), behavioral and cognitive, but not avoidant, coping were significantly lower in the ADHD versus nonADHD group. There were significant inter-correlations among most, but not all, coping measures (behavioral with cognitive, r = .66, p <.01; cognitive with avoidant, r = .34, p <.01; behavioral with avoidant, r = .06, p =.35).

ADHD and anger-irritability

As can be seen in Table 1, paths b and c were estimated by regressing the adolescent alcohol use outcomes on ADHD group in Step 1 and anger-irritability in Step 2. In Step 1, the main effect of childhood ADHD was positively associated with the adolescent drinking outcomes. In Step 2, anger-irritability was positively associated with frequency of drunkenness and alcohol problems but not frequency of binge drinking.

Table 1.

Regression of alcohol use on ADHD group and anger-irritability

| Frequency of Binge Drinking | Frequency of Drunkenness | Alcohol Problems | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||

| Age | .30*** | .32*** | .31*** |

| ADHD Group (Path c) | .15* | .15* | .15* |

| Total R2 | .11 | .12 | .12 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Age | .32*** | .35*** | .35*** |

| ADHD Group (Path c) | .09 | .06 | .03 |

| Anger-irritability (Path b) | .10 | .15* | .22** |

| Total R2 | .12 | .14 | .15 |

Note: Values in the table are standardized regression coefficients.

p ≤ .001,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .05

As can be seen in Tables 2a (for analyses of behavioral coping) and 2b (for analyses of cognitive coping), the standardized beta for the relation between ADHD and anger-irritability (path a) was significant, t(235) = 10.87, p < .001, indicating that adolescents in the ADHD group exhibited higher levels of anger-irritability compared to the nonADHD group. Older age was associated with less anger-irritability, t(235) = −3.76, p < .001.

Table 2.

Regression of anger-irritability on ADHD group and behavioral (2a) and cognitive coping (2b)

| 2a) | |

|---|---|

| Anger-irritability | |

| Step 1 | |

| Age | −.18*** |

| ADHD Group(Path a) | .56*** |

| Total R2 | .35 |

| Step 2 | |

| Age | −.17*** |

| ADHD Group(Path a) | .46*** |

| Behavioral Coping (Path d) | −.28*** |

| Total R2 | .42 |

| Step 3 | |

| Age | −.18*** |

| ADHD Group(Path a) | .47*** |

| Behavioral Coping (Path d) | −.07 |

| Group x Coping interaction | −.27*** |

| Total R2 | .45 |

| 2b) | |

|---|---|

| Anger-irritability | |

| Step 1 | |

| Age | −.18*** |

| ADHD Group (Path a) | .56*** |

| Total R2 | .35 |

| Step 2 | |

| Age | −.15** |

| ADHD Group(Path a) | .46*** |

| Cognitive Coping (Path d) | −.28*** |

| Total R2 | .42 |

| Step 3 | |

| Age | −.15** |

| ADHD Group(Path a) | .47*** |

| Cognitive Coping (Path d) | −.16* |

| Group x Coping interaction | −.15 (p = .06) |

| Total R2 | .43 |

Note: values are standardized regression coefficients;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

Results of the bootstrapping procedures revealed a statistically significant mediational pathway from childhood ADHD to anger-irritability to alcohol problems (B = .92, CI: .32–1.74), but not to frequency of drunkenness (B= .25, CI: −.05–.60).

As published previously (Molina et al., 2005), 72% of the ADHD group met DSM-III-R criteria for ADHD as adolescents. Thirty percent (versus 8% of the nonADHD group, χ2 = 16.17, p < .01) met DSM-III-R criteria for ODD as adolescents. Thus, in order to assess the contribution of persisting ADHD symptoms, as well as the remaining ODD symptoms, on our statistically significant findings for alcohol problems (paths b and c), we regressed alcohol problems on age and ADHD group in Step 1, anger-irritability in Step 2, defiant and vindictive symptoms (the remaining ODD symptoms) in Step 3, and adolescent ADHD symptoms in Step 4. Step 3 results revealed that the significant effects observed in Step 2 for anger-irritability were no longer statistically significant (B = .17, p = .19) with the inclusion of the remaining ODD symptoms (B = .05, p = .70). Adolescent ADHD symptoms were not significantly associated with adolescent alcohol problems (B = .09, p = .32). Results did not change after removing ADHD group from the equation or entering adolescent ADHD symptoms before the defiant and vindictive ODD variable. Anger-irritability, defiance and vindictiveness, and adolescent ADHD symptoms were significantly inter-correlated (anger-irritability with defiance/vindictiveness, r = .85, p < .01; anger-irritability with adolescent ADHD symptoms, r = .52, p <.01; defiance/vindictiveness with adolescent ADHD symptoms, r = .64, p <.01.).

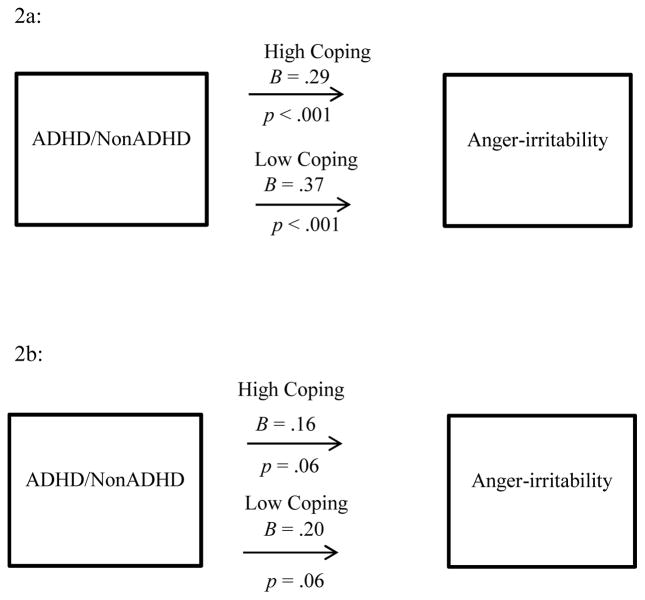

Moderated mediation

As shown in Table 2a (path d; Step 2), behavioral coping, t = −5.05, p < .001 and the ADHD group x behavioral coping interaction (path d; Step 3), t = −3.60, p < .001, were significantly negatively associated with anger-irritability. Figure 2a shows that the association between ADHD group and anger-irritability was relatively stronger for lower, versus for higher, levels of behavioral coping. Thus, ADHD more strongly predicted anger-irritability when behavioral coping was used less often.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a: Behavioral Coping as a moderator of path a:

Figure 2b: Cognitive Coping as a moderator of path a:

Note: Values in the figure are standardized regression coefficients. Unstandardized beta coefficients and Confidence Intervals (CIs) are: Behavioral (High/Low Coping; B=.26, CI = .12–.40 and Cognitive (High/Low Coping; B=.19, CI= .01–.38)

Cognitive coping was also negatively associated with anger-irritability, t = −5. 70, p < .001, and the ADHD group x cognitive coping interaction approached significance, t = −1.91, p = .06 (see Table 2b; Step 3). Due to the modest sample size and associated power for detecting interactions, we explored this interaction and found a trend similar to that for behavioral coping (see Figure 2b). A statistically significant interaction between avoidant coping and ADHD group was not observed, t = .66, p = .51.

Path e analyses examined the effects of coping (behavioral, cognitive, and avoidant) and their interactions with anger-irritability on adolescent alcohol problems and frequency of drunkenness. There were no statistically significant direct (Bs = .01 to .11, p = .11 to .95) or interacting (Bs = .01 to .11, p = .19 to .92) effects of coping on the measured adolescent drinking outcomes.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a facet of emotional dysregulation as a contributing factor to alcohol abuse risk in ADHD. This is important because, unlike the association between childhood ADHD and other substances of abuse, such as cigarettes and marijuana, the relation between ADHD and adolescent alcohol use has been mixed in the literature (Lee et al., 2011). The results of this study help to clarify this relation by demonstrating that anger-irritability may be an important determinant of adolescent alcohol related problems for adolescents with ADHD histories. Of particular clinical interest was the finding that the association between childhood ADHD and adolescent anger-irritability was attenuated when adolescents more frequently used active coping strategies. However, anger-irritability was also highly correlated with the remaining ODD symptoms of defiance and vindictiveness which suggests that outward behavioral expressions of misbehavior are part of this clinical picture. Together, these results have important implications for understanding the nature of the relation between ADHD and adolescent alcohol use and they prompt several directions for future research.

While it is important to note that our understanding of the relation between ADHD and the regulation of emotions is still unclear and in need of further study (Banaschewski, et al., 2012), our finding of more anger-irritability in connection with ADHD is in line with previous studies (Karalunas et al., 2014; Skirrow & Asherson, 2013). For example, Skirrow et al., (2014) found that ADHD was associated with more daily reports of irritability, frustration, and anger. This association held after covarying reported negative events, suggesting that emotional lability is a function of both situational and individual components. As such, individuals with ADHD may experience angry feelings more often than those without ADHD even when environmental triggers are held equal. The intensity and frequency of angry emotions may contribute to their increased risk of alcohol problems as well as negative outcomes in educational, occupational, and social functioning domains (Barkley & Murphy, 2010; Barkley & Fischer, 2010).

Vulnerability to anger-irritability may increase risk for alcohol-related problems because it disrupts healthy decision-making. Individuals with ADHD exhibit a wide range of decision making deficits (Mowinckel, Pedersen, Eilersten, & Biele, 2014). Similarly, individuals at risk for alcohol abuse (Cservenka & Nagel, 2012) as well as alcohol abusers (Bechara et al., 2001) exhibit difficulties in decision making. Cyders & Smith (2008) propose that decision making can be disrupted as a function of elevated negative, as well as positive, affect. As such, what Cyders and Smith (2009) have termed positive and negative urgencies, result in decisions that are poorly conceived and impulsively enacted during periods of heightened mood. Recent work from our group (Pederesen et al, 2016) has shown that both negative and positive urgency mediate the association between ADHD and adult alcohol problems in a longitudinal study of individuals diagnosed with ADHD in childhood. Laboratory based research examining the relation between emotion and decision making has shown that elicited discrete emotions (short lived/intensely experienced phenomena) influence decision making and disrupt pre-existing cognitive processes (for review see, Angie, Connelly, Waples, & Kligyte, 2011). Elicited anger, in particular, may lower appraisal of risk (Angie et al., 2011). Thus, ADHD and anger may together interfere with well-reasoned decision-making when teens are faced with risky behavior choices such as heavy drinking.

We specifically found mediation by anger-irritability for alcohol use-related problems such as getting into arguments and getting into trouble after drinking. Alcohol may have unusually disinhibiting effects among individuals with ADHD (Weafer, Milich, & Fillmore, 2011) and when consumed by persons with volatile emotions, the disinhibiting effect of alcohol may be even more likely to produce alcohol-related problems. This may explain why our findings were strongest for alcohol-related problems compared to consumption (frequency of binge drinking or drunkenness). Individuals who drink to excess and experience problems from drinking have, indeed, been shown to have high scores on a measure of negative urgency (the tendency to act rashly when in a negative mood; Coskunpinar, Dir, & Cyders, 2013). It also explains why the additional ODD symptom items, namely defiance of authority, have strong overlap with anger-irritability in their association with alcohol problems. Future research would benefit from studies designed to test the role of anger-irritability and defiance/vindictiveness as catalysts, independently and jointly, for risky behaviors in general in the development of alcohol problems.

The association between anger-irritability and alcohol problems was no longer significant once the additional ODD symptoms of defiance and vindictiveness were included in the analyses. Past studies have successfully demonstrated unique effects of ODD dimensions on internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Fernández de la Cruz et al 2015), but the association between the ODD dimensions is also consistently strong (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009). Similarly with the adolescent ADHD symptoms, previous studies using these data have reported associations between ADHD persistence and adolescent drinking behaviors (Molina & Pelham, 2003). We did not find such associations and ADHD persistence and symptoms of ODD were highly inter-correlated. Such findings are understandable clinically and speak to the close relations among these variables. Longitudinal studies with multiple time points will be well positioned to further explore these relationships. Additionally, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) may be particularly well-suited for use in future studies of the relationship between anger-irritability and drinking behaviors among individuals diagnosed with ADHD. EMA assesses naturally occurring real time relationships, has been widely used to study substance use behaviors (Shiffman,2009) and been used to measure emotional processes among children with ADHD (Whalen et al., 2009; Rosen & Factor, 2015)

The association between childhood ADHD and anger-irritability was stronger for adolescents who less often used adaptive coping strategies. Interestingly, coping did not moderate the relationship between anger-irritability and adolescent alcohol use. These results suggest that when implemented, higher order cognitive processes, such as adaptive coping, may lessen the risk for experiencing high levels of impulsive angry emotions but that the utility of such cognitive processes may falter in the presence of elevated negative emotional states. Taken together, these results may have significant clinical implications. Evidence-based treatments such as cognitive-behavior treatment (Knouse & Safren, 2010) and dialectical behavioral therapy (Hesslinger, 2002) adapted for individuals diagnosed with ADHD have been shown to reduce emotion-based impairments in adults. Such treatments, resulting in decreased anger and increased utilization of effective coping strategies, for both positive and negative emotions, may have downstream effects on reducing alcohol use.

These findings must be viewed within the context of important study considerations. Anger-irritability and alcohol use were assessed concurrently; prospective multi-wave assessments are needed to strengthen the test of our hypotheses. The generalizability of these findings to a larger population of children with ADHD may be limited as this sample is a follow-up of clinic-referred children. Participation bias was small, but, the relatively low follow-up rate must be noted. Lastly, we believe our choice to use parent-reported anger-irritability and coping is a strength of this study given the limitations of self-report in this population (Hoza et al., 2002; Sibley et al., 2012) and that previous peer-reviewed studies have employed similar strategies (Stringaris et al, 2009).

Despite these study features, the current study provides new information about an alcohol use disorder risk factor among adolescents with ADHD histories. Specifically, this study is the first to demonstrate that anger-irritability mediates the association between childhood ADHD and alcohol use problems in adolescence. Importantly, our findings suggest that adaptive coping strategies are associated with less anger-irritability among children with ADHD. Additional studies are needed, including integration of these findings with the other risk pathways that have previously been articulated (e.g., Molina & Pelham, 2014). The current study results suggest that future interventions aimed at reducing negative outcomes among individuals diagnosed with ADHD may benefit from the inclusion of active coping strategies to increase the management of negative and angry emotions. Any impact on the full complement of ODD symptoms will also be important to consider.

Key points.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in childhood is a risk for later substance use and substance use disorders. Results describing the association between childhood ADHD and adolescent alcohol have been mixed.

Proneness toward anger and irritability has been separately associated with ADHD and alcohol use.

This study tested anger-irritability as a mediator of ADHD risk for adolescent alcohol use and the degree to which such associations were moderated by coping strategies.

Anger-irritability mediated the association between ADHD and alcohol use problems and behavioral and cognitive coping moderated the association between childhood ADHD and anger-irritability.

Coping strategies may help reduce negative emotions among adolescents with ADHD which may lessen vulnerability to adolescent alcohol problems.

Acknowledgments

Grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA00202; AA011873; AA08746) provided the primary support for this study. Additional funding was provided by AA007453; DA12414; DA05605; AA06267; MH50467; MH12010, T32 AA007453, T32 MH018951-21. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- Angie AD, Connelly S, Waples EP, Kligyte V. The influence of discrete emotions on judgement and decision-making: A meta-analytic review. Cognition & Emotion. 2011;25(8):1393–1422. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.550751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Pelham WE, Licht MH. A comparison of objective classroom measures and teacher ratings of attention deficit disorder. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 1985;13(1):155–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00918379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb KA, Levine LJ, Arseneault JM. Shifting gears: Coping flexibility in children with and without ADHD. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34(1):10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Molina BSG, Kashdan TB, Pelham WE, Hoza B. Anxiety and mood disorders in adolescents with childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2006;14(3):178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Banaschewski T, Jennen-Steinmetz C, Brandeis D, Buitelaar JK, Kuntsi J, Poustka L, … Chen W. Neuropsychological correlates of emotional lability in children with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(11):1139–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(4):546–557. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M. The unique contribution of emotional impulsiveness to impairment in major life activities in hyperactive children as adults. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):503–513. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Impairment in occupational functioning and adult ADHD: the predictive utility of executive function (EF) ratings versus EF tests. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2010;25(3):157–173. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acq014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1986;51(6):1173. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Dolan S, Denburg N, Hindes A, Anderson SW, Nathan PE. Decision-making deficits, linked to a dysfunctional ventromedial prefrontal cortex, revealed in alcohol and stimulant abusers. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39(4):376–389. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(5):564–577. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.5.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Faraone SV, Weber W, Curtis S, Soriano J. Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(1):21–29. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Hipwell AE, Loeber R. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder as predictors of depression and conduct disorder in preadolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):484–492. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201005000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol Use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(9):1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of personality. 2000;68(6):1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cservenka A, Nagel BJ. Risky Decision-Making: An fMRI Study of Youth at High Risk for Alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(4):604–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DA, Gadow KD. Deconstructing oppositional defiant disorder: clinic-based evidence for an anger/irritability phenotype. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(4):384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftekhari A, Turner AP, Larimer ME. Anger expression, coping, and substance use in adolescent offenders. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(5):1001–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Granero R, de la Osa N, Penelo E, Domènech JM. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in 3-year-old preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(11):1128–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de la Cruz LF, Simonoff E, McGough JJ, Halperin JM, Arnold LE, Stringaris A. Treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and irritability: results from the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanizadeh A, Haghighi HB. How do ADHD children perceive their cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects of anger expression in school setting? Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health. 2010;4(4) doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF. Normative data on revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:221–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00919127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel P, Manhal S, Roos T, Desman C. Interpersonal coping among boys with ADHD. Journal of attention disorders. 2008;11(4):427–436. doi: 10.1177/1087054707299337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hesslinger B, van Elst LT, Nyberg E, Dykierek P, Richter H, Berner M, Ebert D. Psychotherapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2002;252(4):177–184. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Pelham WE, Jr, Dobbs J, Owens JS, Pillow DR. Do boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder have positive illusory self-concepts? Journal of abnormal psychology. 2002;111(2):268. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Chassin L. Stress and coping among children of alcoholic parents through the young adult transition. Development and psychopathology. 2004;16(04):985–1006. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa FM. Health behavior questionnaire. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Karalunas SL, Fair D, Musser ED, Aykes K, Iyer SP, Nigg JT. Subtyping attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using temperament dimensions: toward biologically based nosologic criteria. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1015–1024. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Kaiser AJ, Milich R, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ. Negative urgency, distress tolerance, and substance abuse among college students. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37(10):1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse LE, Safren SA. Current status of cognitive behavioral therapy for adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33(3):497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosomatic medicine. 1993;55(3):234–247. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, Liu R, Glass K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(3):328–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney J, Milich R. Hyperactivity, inattention, and aggression in clinical practice. In: Wolraich M, Routh DK, editors. Advances in developmental and behavioral pediatrics. Vol. 3. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1982. pp. 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation review. 1993;17(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Molina BSG, Pelham WE. Childhood ADHD and adolescent substance use: An examination of deviant peer group affiliation as a risk factor. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(4):293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM. Research Review: A new perspective on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: emotion dysregulation and trait models. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1042–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Kaczynski NA, Maisto SA, Bukstein OG, Moss HB. Patterns of DSM–IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:672–680. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Pollock NK, Lynch KG, Bukstein OG. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID substance use disorder section in adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Marshal MP, Pelham WE, Wirth RJ. Coping skills and parent support mediate the association between childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and adolescent cigarette use. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2005;30(4):345–357. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Pelham WE., Jr Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(3):497–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, Pelham WE, Hechtman L, … Greenhill LL. Adolescent substance use in the multimodal treatment study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)(MTA) as a function of childhood ADHD, random assignment to childhood treatments, and subsequent medication. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(3):250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Pelham WE., Jr Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and risk of substance use disorder: Developmental considerations, potential pathways, and opportunities for research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:607–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowinckel AM, Pedersen ML, Eilertsen E, Biele G. A Meta-Analysis of Decision-Making and Attention in Adults With ADHD. Journal of attention disorders. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1087054714558872. 1087054714558872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) OMB No.0930-0110. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, and Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration. National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, Lochman J, Wells K. Negative emotions and alcohol use initiation in high-risk boys: The moderating effect of good inhibitory control. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2004;32(5):505–518. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000037780.22849.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2004;65(1):126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Jr, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, Milich R. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(2):210–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez CA, Rosén LA, Deffenbacher JL, Hurst H, Nicoletta C, Rosencranz T, Smith K. Anger and anger expression in adults with high ADHD symptoms. Journal of Attention Disorders. 1997;2(2):115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen PJ, Factor PI. Emotional impulsivity and emotional and behavioral difficulties among children with ADHD an ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2015;19(9):779–793. doi: 10.1177/1087054712463064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Stringaris A, Nigg J, Leibenluft E. Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171(3):276–293. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21(4):486. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Waschbusch DA, Garefino A, Kuriyan AB, Babinski DE, Karch KM. Diagnosing ADHD in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(1):139–150. doi: 10.1037/a0026577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Jr, Molina BS, Coxe S, Kipp H, Gnagy EM, … Lahey BB. The role of early childhood ADHD and subsequent CD in the initiation and escalation of adolescent cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2014;123(2):362. doi: 10.1037/a0036585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirrow C, Asherson P. Emotional lability, comorbidity and impairment in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2013;147(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirrow C, Ebner-Priemer U, Reinhard I, Malliaris Y, Kuntsi J, Asherson P. Everyday emotional experience of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: evidence for reactive and endogenous emotional lability. Psychological medicine. 2014;44(16):3571–3583. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobanski E, Banaschewski T, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Chen W, Franke B, … Faraone SV. Emotional lability in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): clinical correlates and familial prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(8):915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon B. Instruction manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Clinical psychology review. 2013;33(4):574–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: irritable, headstrong, and hurtful behaviors have distinctive predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):404–412. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Psych MRC, Cohen P, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: a 20-year prospective community-based study. The American journal of psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1048–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, Valdivieso I, Leibenluft E, Stringaris A. The Status of Irritability in Psychiatry: A Conceptual and Quantitative Review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT, Milich R. Increased sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol in adults with ADHD. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17(2):113. doi: 10.1037/a0015418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Milich R, Fillmore MT. Behavioral components of impulsivity predict alcohol consumption in adults with ADHD and healthy controls. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011;113(2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler intelligence scale for children. 3. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Barkley RA. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen CK, Henker B, Ishikawa SS, Floro JN, Emmerson NA, Johnston JA, Swindle R. ADHD and anger contexts: Electronic diary mood reports from mothers and children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:940–953. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Stress and coping in early adolescence: relationships to substance use in urban school samples. Health psychology. 1986;5(6):503. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.5.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, Shinar O. Coping dimensions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: a latent growth analysis. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2001;110(2):309. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Walker C, Mendoza D, Ainette MG. Behavioral and emotional self-control: relations to substance use in samples of middle and high school students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(3):265. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray TB, Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Gaher RM. Trait-based affective processes in alcohol-involved ‘risk behaviors’. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37(11):1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S. Coping strategies used by adults with ADHD. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38(4):809–816. [Google Scholar]