Abstract

Aeromonas media is an opportunistic pathogen for human and animals mainly found in aquatic habitats and which has been noted for significant genomic and phenotypic heterogeneities. We aimed to better understand the population structure and diversity of strains currently affiliated to A. media and the related species A. rivipollensis. Forty-one strains were included in a population study integrating, multilocus genetics, phylogenetics, comparative genomics, as well as phenotypics, lifestyle, and evolutionary features. Sixteen gene-based multilocus phylogeny delineated three clades. Clades corresponded to different genomic groups or genomospecies defined by phylogenomic metrics ANI (average nucleotide identity) and isDDH (in silico DNA-DNA hybridization) on 14 whole genome sequences. DL-lactate utilization, cefoxitin susceptibility, nucleotide signatures, ribosomal multi-operon diversity, and differences in relative effect of recombination and mutation (i.e., in evolution mode) distinguished the two species Aeromonas media and Aeromonas rivipollensis. The description of these two species was emended accordingly. The genome metrics and comparative genomics suggested that a third clade is a distinct genomospecies. Beside the species delineation, genetic and genomic data analysis provided a more comprehensive knowledge of the cladogenesis determinants at the root and inside A. media species complex among aeromonads. Particular lifestyles and phenotypes as well as major differences in evolution modes may represent putative factors associated with lineage emergence and speciation within the A. media complex. Finally, the integrative and populational approach presented in this study is considered broadly in order to conciliate the delineation of taxonomic species and the population structure in bacterial genera organized in species complexes.

Keywords: population study, integrative taxonomy, Aeromonas, speciation, complex of species, taxogenomics, phylogeny, recombination

Introduction

The genus Aeromonas groups ubiquitous bacteria mainly found in aquatic habitats. Among the 30 taxonomic species currently described in the genus, half were characterized since the latest edition of the Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology in 2005 (Martin-Carnahan and Joseph, 2005). Taxonomy in the genus is subject to controversies leading to several reclassifications (Beaz-Hidalgo et al., 2013). The main reason is the organization of Aeromonas in several species complexes, heterogeneous groups of related but genetically distinct strains. Taxonomic focus on a species complex generally leads to the delineation of new species from the most homogeneous groups inside the complex. Consequently, an increasing number of new species are described in the genus, but some of these descriptions lead to subsequent controversies about their delineation and robustness.

Aeromonas media is one typical example among others. Heterogeneity in the complex Aeromonas media was recognized early after its description because it was split in two DNA-DNA hybridization groups (HG), HG5A and HG5B represented by strains Popoff 233 and 239, respectively (Altwegg et al., 1990). The type strain A. media CECT 4232T groups into HG5B (Altwegg et al., 1990). A. media has been described in river freshwater (Allen et al., 1983) and was then found in sewage water, activated sludge, drinking water, animals and human (Picao et al., 2008; Pablos et al., 2009; Figueira et al., 2011; Roger et al., 2012a). A. media acts as an opportunistic emerging pathogen causing a wide spectrum of diseases in human and animals (Beaz-Hidalgo et al., 2010; Figueras and Beaz-Hidalgo, 2015). It causes skin ulcers in fish and diarrhea in human, but with lower prevalence than other clinically relevant Aeromonas species (Singh, 2000; Parker and Shaw, 2011; Figueras and Beaz-Hidalgo, 2015).

The intra-species heterogeneity of A. media was confirmed by 16S rRNA gene, rpoB and gyrB sequencing that showed that strains distributed into two subgroups corresponding to the HG subgroups (Küpfer et al., 2006). Considering phenotype, every HG5B strain but no HG5A strains utilizes DL-lactate (Altwegg et al., 1990). A new species related to A. media, A. rivipollensis was recently described (Marti and Balcázar, 2015; Oren and Garrity, 2016) but was not positioned into any of the HG subgroups. In addition, A. media displays distinctive genetic features compared to other Aeromonas species: (i) a genetic polymorphism showed by 7 gene-multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) higher than that of any other species within the genus (5.8% vs. a mean of 2.5% for other species) (Roger et al., 2012a), (ii) a high heterogeneity in the tRNA genes intergenic spacers (Laganowska and Kaznowski, 2005), (iii) one of the highest rate of intragenomic heterogeneity among rrn operons (Alperi et al., 2008; Roger et al., 2012b), and (iv) a strikingly high diversity of rrn chromosomal distribution (Roger et al., 2012b). However, all above studies were not designed for assessing the heterogeneity in A. media and included a rather low number of A. media strains. HG subgroups and the heterogeneity observed suggested that A. media and the related species A. rivipollensis formed a species complex (SC) referred hereafter as “Media SC.”

In such a context, population studies are powerful means to investigate heterogeneity within a complex of species (Vandamme and Dawyndt, 2011). This work aimed to perform an integrative approach to structure a population of 41 strains (14 whole genome sequences) from different habitats and geographical regions affiliated to Media SC. In the context of species complex, recombination events have been particularly taken into consideration. Beyond the population-based reappraisal of the phylotaxonomy, Media SC is taken as an outstanding test case to discuss the conflicts between species delineation and population structure in bacteria, and to highlight how the population studies can reinforce knowledge in taxonomy.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and DNA extraction

A total of 40 A. media previously identified by gyrB sequencing were analyzed (Table 1), including the type strain of A. media (CECT 4232T), and reference strains for HG5A (A. caviae LMG 13459) and HG5B (A. caviae LMG 13464). Fifty-four strains belonging to 30 other species of Aeromonas were also studied, including the type strain of every species with validated name of which the new species A. rivipollensis Marti and Balcazar 2016 (LMG 26323T) (Marti and Balcázar, 2015; Oren and Garrity, 2016). Strains were grown on Trypticase Soy Agar at 35°C for 16–24 h, and genomic DNA were extracted using the MasterPure™ DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre, USA). All the bacterial experiments were performed at Biosafety Level 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 41 strains affiliated to Media species complex on the basis of gyrB sequences analyzed in this study.

| Strain | Clade in MLP | Genome accession number | Sample | Origin | Country (Date of isolation) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. media CCM 4242 | A | River water | Environment | Czech republic (1991) | Sedlácek et al., 1994 | |

| A. rivipollensis LMG 26313T | A | River biofilm (output WWTP) | Environment | Spain (2010) | Marti and Balcázar, 2015 | |

| LL6-17C | A | River water (output WWTP) | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| SS1-15D | A | WWTP | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| CR4.2-17C | A | River water | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| A. hydrophila 4AK4a | A | PRJNA210524b | Raw sewage | Environment | NA (NA) | Gao et al., 2013 |

| A. caviae LMG 13459 = Popoff 239 | A | PRJEB12346b | Fish (infected) | Animal | France (1967-1974) | Popoff and Véron, 1976 |

| A. media AK202 | A | PRJEB12343b | Snail | Animal | France (1995) | Roger et al., 2012b |

| AK208 | A | Snail | Animal | France (1995) | This study | |

| AK210 | A | Snail | Animal | France (1995) | This study | |

| A. hydrophila AH31 | A | Crab | Animal | Norway (1998) | Granum et al., 1998 | |

| R1 | A | Salmon | Animal | Spain (2007) | This study | |

| R100 | A | Trout | Animal | Spain (2007) | This study | |

| 417-16G | A | Mussel | Animal | Spain (2011) | This study | |

| M2C164 = M2C A28 | A | Copepod | Animal | France (2012) | This study | |

| M2C185 = M2C A42 | A | Copepod | Animal | France (2012) | This study | |

| M2C205 = M2C A47 | A | Copepod | Animal | France (2012) | This study | |

| A. media 76C | A | PRJEB8966b | Human diarrheic stool | Clinical | Spain (1992) | Mosser et al., 2015 |

| BVH17 | A | Human urine (healthy carriage) | Clinical | France (2006) | This study | |

| A. media BVH40 | A | PRJEB8017b | Human stool (healthy carriage) | Clinical | France (2006) | Roger et al., 2012a |

| ADV137a | A | Human respiratory tract (near-drowning) | Clinical | France (2010) | This study | |

| A. media CECT 4232T = RM | B | PRJEB7032b | River water (fish farm effluent) | Environment | UK (1980) | Allen et al., 1983 |

| A. media CECT 4234 = P1E | B | River water (fish farm pond) | Environment | UK (1981) | Allen et al., 1983 | |

| T41-3 | B | Soil | Environment | Spain (2010) | This study | |

| T41-7 | B | Soil | Environment | Spain (2010) | This study | |

| RT10-17Ga | B | River water | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| RT11-17Ga | B | River water | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| LL4.4-18D | B | River water (input WWTP) | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| SEL1-18A | B | WWTP | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| CR4-18pb | B | River water | Environment | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| A. media ARB13a | B | PRJNA260228c | River water | Environment | Japan (2013) | Kenzaka et al., 2014 |

| A. media ARB20a | B | PRJNA260227c | River water | Environment | Japan (2013) | Kenzaka et al., 2014 |

| A. media WSa | B | CP007567.1c | Lake water | Environment | China (2003) | Chai et al., 2012 |

| A. caviae LMG 13464 = Popoff 233 | B | PRJEB12347b | Fish (infected) | Animal | France (1967-1974) | Popoff and Véron, 1976 |

| AK207 | B | Snail | Animal | France (1995) | This study | |

| A. media AK211 | B | PRJEB12344b | Snail | Animal | France (1995) | Roger et al., 2012a |

| Aeromonas sp. CECT 7111 | B | PRJEB12345b | Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) | Animal | Spain (2002) | Miñana-Galbis et al., 2002 |

| BVH83 | B | Human urine (healthy carriage) | Clinical | France (2006) | This study | |

| D84402 | B | Human diarrheic stool | Clinical | Spain (2012) | This study | |

| A. eucrenophila UTS 15 | C | PRJEB12350b | Koi carp | Animal | Australia (2001) | Carson et al., 2001 |

| 1086C = CECT 8838 = LMG 28708 | C | PRJEB12349b | Human diarrheic stool | Clinical | Spain (2010) | This study |

Several strains were wrongly labeled at the time of their isolation but all the 41 strains belonged to the Media SC on the basis of gyrB sequences that is robust enough for their affiliation within the genus Aeromonas, as explained in the main text.

MLP, Multi-Locus Phylogeny; NA, Not available; WWTP, Waste water treatment plant.

Strains studied only by genetic and genomic analysis.

Obtained from the EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database.

Obtained from GenBank, National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Phenotypic characterization

Methods are given in the Supplementary Taxonomic Sheet.

Gene amplification and sequencing

The 16S rRNA genes and 16 housekeeping (HK) genes described in three MLSA schemes (atpD, dnaJ, dnaK, dnaX, gltA, groL, gyrA, gyrB, metG, ppsA, radA, recA, rpoB, rpoD, tsf, and zipA) were amplified using primers and PCR conditions previously described (Carlier et al., 2002; Martinez-Murcia et al., 2011; Martino et al., 2011; Roger et al., 2012b). For strains affiliated to A. media, the oligonucleotide zipA-Rmed (5′-CATGTTGATCATGGAGAAGAGC-3′) was designed in this study and used as reverse primer for zipA amplification. Amplification products were sequenced using either forward primers (housekeeping genes) or both forward and reverse primers (16S rDNA) on an ABI 3730XL automatic sequencer (Beckman Coulter Genomics, France).

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogeny was inferred from gene sequences produced in this study or downloaded from GenBank. Gene sequences were aligned using the Clustal ω2 program within Seaview 4 package (Gouy et al., 2010). PhyML trees were reconstructed for (i) every 16 individual HK locus and 16S rRNA gene (Single Locus Phylogeny, SLP), (ii) the concatenated HK loci (Multi Locus Phylogeny, MLP), (iii) the concatenated translated amino acid sequences, and (iv) for the concatenated codon-aligned nucleotidic HK sequences excluding third position. Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees were reconstructed from nucleotidic sequences using a GTR model plus gamma distribution and invariant sites as substitution model, in PhyML v3.1 program. The ML tree was reconstructed from concatenated amino acid sequences using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model (Jones et al., 1992). ML bootstrap supports were calculated after 100 reiterations. Models used were determined to be the most appropriate after Akaike criterion calculation by IQ-TREE at http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/.

Study of genetic recombination

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) was detected from the concatenated sequences using a polyphasic approach. The program LIAN v3.7, available at http://www.pubmlst.org, was used to calculate the standardized index of association (IsA), to test the null hypothesis of linkage disequilibrium, and to determine mean genetic diversity (H) and genetic diversity at each locus (h). A distance matrix in nexus format was generated from the set of allelic profiles and then used for decomposition analyses with the neighbor-net algorithm available in SplitsTree 4.0 software (Huson and Bryant, 2006). Recombination events were detected using the pairwise homoplasy index test, φw (Bruen et al., 2006), implemented in SplitsTree 4.0 and the RDP v3.44 software package (Martin et al., 2010) with the basic parameters, as described elsewhere (Roger et al., 2012a). Only positive recombination events supported by at least four of the seven methods used in RDP were taken into account.

Five independent runs of ClonalFrame (Didelot and Falush, 2007) with 300,000 iterations were performed on the whole strain population and within specific lineages for the estimation of ρ/θ (relative rate of recombination and mutation) and r/m (relative effect of recombination and mutation). We fixed values of δ, the mean tract length of imported sequence fragment, at 412 bp which is the value inferred during the five runs performed on the whole dataset, and of the mutation rate to the Watterson's moment estimator θW obtained from the whole population or from each lineage population (Chaillou et al., 2013).

RIMOD (ribosomal multi operon diversity)

For rrn numbering and chromosome distribution study, intact genomic DNA was prepared in agarose plugs as previously described (Roger et al., 2012b). Number of rrn copies was deduced from the number of I-CeuI-generated fragments. The Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) profiles were visually compared and both shared and distinct DNA fragments were numbered. Size of PFGE bands were measured by comparison with lambda concatemer ladder (New England BioLabs) used as size standard. For studying intragenomic rrs heterogeneity, amplification by PCR of a 199 bp fragment overlapping the 16S rRNA gene variable region V3, Temporal Temperature Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (TTGE), and band analysis and sequencing were performed as previously described (Roger et al., 2012b). TTGE bands and profiles were numbered according to Roger et al. (2012b) with increment for previously undescribed bands.

Genome sequencing and analysis

Ten strains were sequenced at the Microbial Analysis, Resources and Services (MARS) facility at the University of Connecticut (Storrs, USA) with the Illumina MiSeq benchtop sequencer, as described previously (Colston et al., 2014), after preparing libraries from the genomic DNA using NexteraXT DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Paired Illumina reads were trimmed and assembled into scaffolded contigs using the de novo assembler of CLC Genomics Workbench versions 6.0.04 to 7.0.04 (CLC-bio, Aarhus, Denmark) (Supplementary Table 1). Four other whole genome sequences (WGS) were downloaded from public databases on 6 November 2014 (Supplementary Table 1). Genomic contigs and circular genomes were annotated by using the RAST annotation server (Overbeek et al., 2014). Assembled contigs were reconstituted from RAST to generate GenBank files for all genomes using the seqret function of the EMBOSS package (Rice et al., 2000). Homologous translated genes were identified using the program GET_HOMOLOGUES which uses a BLASTP bidirectional best-hit approach with OrthoMCL and COG clustering algorithms (Contreras-Moreira and Vinuesa, 2013). Four clusters of genes were determined from the pangenome analysis: core-genome present in all the genomes, softcore-genome present in 95% (n = 13) of the genomes, shell-genome present in ≥3 and <13 genomes and cloud-genome present in ≤ 2 genomes. The parse_pangenome_matrix.pl script was employed to extract the specific conserved genome of selected lineages. Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) was determined using the Jspecies package 1.2.1 (Richter and Rosselló-Móra, 2009) and default parameters. An estimate of in silico DNA-DNA Hybridization (isDDH) was made using genome-to-genome distance calculator (GGDC) (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013). The contig files were uploaded to the GGDC 2.0 webserver (http://ggdc.dsmz.de/distcalc2.php), and isDDH was calculated using formula 2, independent of genome length, as recommended by the authors of GGDC for use with any incomplete genomes. Genome sizes and G + C DNA contents were estimated in silico after WGS analysis by RAST.

Statistics

All qualitative variables, with the exception of the IsA and ClonalFrame results, were compared using a Chi-squared test, the Fisher's exact test or the Student's test where appropriate; P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All these computations were performed using R project software (http://www.r-project.org). The congruence of results obtained with MLP analysis, PCR-TTGE and PFGE were evaluated with the adjusted Wallace coefficient with 95% confidence interval (CI). Calculations were done using the Comparing Partitions website (www.comparingpartitions.info). Satisfactory convergence of the Markov Chain Monte Carlo, MCMC, in the different runs of ClonalFrame was estimated based on the Gelman-Rubin statistic implemented in the software (Didelot and Falush, 2007).

Nucleotide sequence and genome accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KP400769 to KP401575 and KU756255 to KU756265 (HK), KP717966 to KP718060 and KX553956 to KX553959 (V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene), KT934807 to KT934809 and KU363310 to KU363342 (almost complete 16S rRNA gene). The genomic sequences determined in this study were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database with the accession numbers referenced in Table 1, and are also available for query and download at http://aeromonasgenomes.uconn.edu.

Results

Collection representativeness

The gyrB gene was selected as an acceptable marker because it is both accurate enough to discriminate between A. rivipollensis and A. media strains (Media SC sequence similarity ≥94.6%, interspecies similarity ≤ 95.3%), and it is widely used for characterizing Aeromonas strains (Supplementary Taxonomic Sheet).

The gyrB sequence of A. media CECT 4232T (JN829508, 780 bp) used as query for Megablast analysis detected 125 sequences in NCBI database (30 November 2014, cut-off values of 96% for identity and 50% for query-cover, excluding uncultivated and redundant entry) including 113 strains for which isolation source was known. These 113 strains have been considered for habitat, distribution and pathogenicity. The strains were mainly from environmental (58%) or animal non-human (41%) origin, and 1% of strains were from human origin, a distribution roughly similar to that of the population we studied: 44% of environmental strains, 39% of animal non-human strains and 17% of human clinical strains (Table 1). Redundancy in our population was limited to 2 pairs of strains, including one pair from snails of the same husbandry (AK207 and AK211) and one pair from river water in Japan (ARB13 and ARB20). However, all these strains except ARB13 and ARB20 differed in their sequences as showed in the MLP analysis below (Figure 1). The collection used in this study was representative of the known lifestyles of members of Media SC and presented low redundancy.

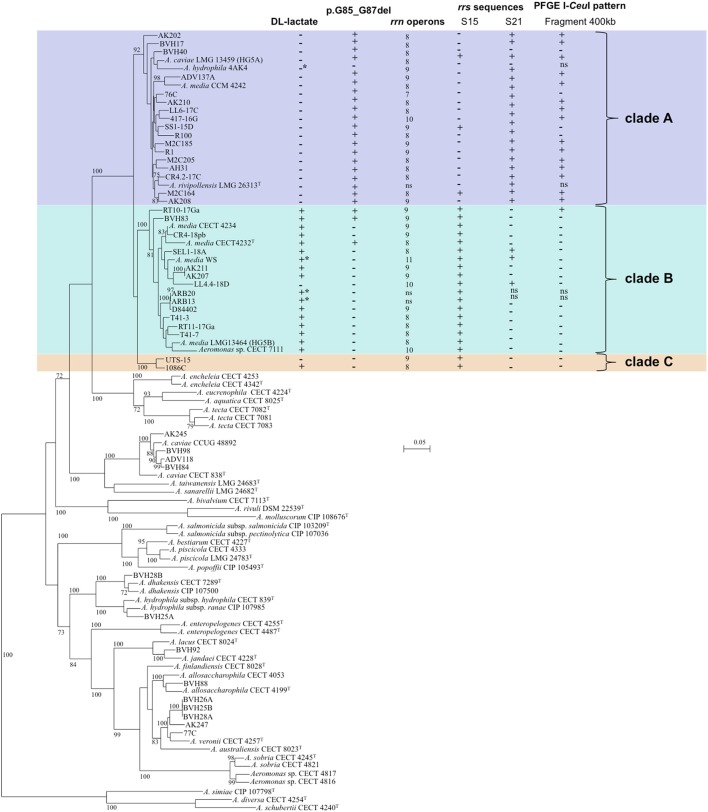

Figure 1.

Unrooted Maximum-Likelihood tree based on concatenated sequences of 16 housekeeping gene fragments (9,427 nt.) from 3 MLST schemes. The tree shows the phylogenetic structure of the studied Media species complex population and the relative placement of strains to other recognized species in the genus. The horizontal lines represent genetic distance, with the scale bar indicating the number of substitutions per nucleotide position. The numbers at the nodes are support values estimated with 100 bootstrap replicates. Only bootstrap values ≥70 are indicated. The following characteristics are indicated for strains affiliated to A. media from left to right: (i) DL-lactate utilization, (ii) presence/absence of a 3 amino acid deletion (p.G85_G87del†), corresponding to a deletion of 9 nucleotides (c.3357226_3357234del††), (iii) number of rrn operons, (iv) presence/absence of 16S rRNA gene sequences S15 and/or S21 (corresponding to PCR-TTGE bands No. 15 and/or No. 21) revealed either by analysis of WGS or PCR-TTGE pattern, (v) presence/absence of DNA fragment of about 400 kb in PFGE I-CeuI pattern. The type strain of Aeromonas fluvialis was not included in the phylogenetic tree either because we failed to amplify the locus ppsA. This species did not group with Media complex in a 7 gene (atpD, dnaJ, dnaX, gyrA, gyrB, recA, rpoD)-based tree. *DL-lactate utilization or absence inferred from genomic analysis; +, positive; −, negative; ns, not studied. †position on the chaperone protein DnaJ sequence of A. hydrophila subsp. hydrophila ATCC 7966T (GenBank ABK39448.1). ††position on the circular chromosome sequence of A. hydrophila subsp. hydrophila ATCC 7966T (NCBI Reference Sequence NC_008570.1).

Multilocus phylogeny in the genus Aeromonas

Phylogenetic relationships among studied strains and in the genus Aeromonas are shown on the 16 gene concatenated sequence-based tree (Figure 1). The concatenated sequence allowed the reconstruction of a robust MLP of the genus, and each species formed an independent lineage. The SLP showed lower bootstrap values compared to the multi-locus tree. Phylogeny excluding the third position of codons and protein-based phylogeny displayed lower bootstrap values indicating the low level of homoplasy in the data.

The 40 A. media strains and the type strain of A. rivipollensis were clustered in a robust MLP lineage (bootstrap value 100%), corresponding to Media SC, clearly distinct from other Aeromonas species, and contained 3 distinct clades (bootstrap values ≥92%). The clade A contained 21 strains, including the HG5A reference strain LMG 13459 and the type strain A. rivipollensis LMG 26323T (Figure 1). The clade B grouped 18 strains, including the HG5B reference strain LMG 13464 and the type strain A. media CECT 4232T, and the clade C contained 2 strains.

The mean genetic diversity (H) among strains was similar in the 2 main clades (0.9702 and 0.9085 for clades A and B, respectively) (Table 2). The rate of polymorphic sites at each locus was not different between the clades A and B (P-value = 0.1). However, on the basis of ClonalFrame analysis, strains in clade A were affected by more mutation events between isolates and their most recent common ancestor than those in clade B, 55 and 3, respectively (Table 2). Some mutations were clade-specific. A deletion of 3 consecutive amino acids (G-F-G), pG85_G87del (A. hydrophila subsp. hydrophila ATCC 7966T numbering) was detected in the sequence of the chaperone protein DnaJ. This deletion was present in all strains of the clade A with the exception of the strain 4AK4, and in only three strains belonging to clade B (Figure 1; P-value < 0.0001). In addition, three specific positions in the aligned gyrB sequences (508, 609, and 627) distinguished the 3 clades.

Table 2.

Genetic diversity, phylogenetic discrepancies in single locus phylogeny (SLP) analysis and ClonalFrame analysis of bacteria in the Media SC according to the population structure observed in multi-locus phylogeny analysis.

| Clade A (n = 21) | Clade B (n = 18) | Clades A, B, and C (n = 41) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized index of association (IsA) | 0.019 (P-value = 0.005) | 0.310 (P-value < 0.0001) | 0.222 (P-value < 0.0001) | |||||||||

| Mean genetic diversity (H) | 0.9702 ± 0.0172 | 0.9085 ± 0.0132 | 0.9730 ± 0.0053 | |||||||||

| No of alleles | Poly-morphic sites % | h, genetic diversity | Strains with phylogenetic discrepancies in SLP (most closely related clade) | No of alleles | Poly-morphic sites % | h, genetic diversity | Strains with phylogenetic discrepancies in SLP (most closely related clade) | No of alleles | Polymorphic sites (%) | h, genetic diversity | ||

| Genetic diversity and phylogenetic discrepancies at each locus | atpD (501 bp) | 18 | 7 | 0.9810 | AH31 (clade A. encheleia) | 10 | 2 | 0.9020 | − | 30 | 8 | 0.9768 |

| dnaJ (785–794 bp) | 20 | 6 | 0.9952 | − | 13 | 7 | 0.9477 | BVH83, CECT 4232T, RT10-17Ga, CECT 7111, LL4.4-18D (clade A) | 34 | 13 | 0.9866 | |

| dnaK (812 bp) | 20 | 5 | 0.9905 | − | 12 | 16 | 0.9739 | − | 34 | 19 | 0.9902 | |

| dnaX (496 bp) | 20 | 12 | 0.9952 | AK202 (clade A. caviae) | 12 | 9 | 0.9150 | − | 34 | 16 | 0.9829 | |

| gltA (433 bp) | 19 | 10 | 0.9905 | LMG 26323 (clade B) | 8 | 3 | 0.7516 | − | 29 | 12 | 0.9512 | |

| groL (510 bp) | 18 | 7 | 0.9810 | − | 12 | 4 | 0.9346 | − | 31 | 11 | 0.9817 | |

| gyrA (469 bp) | 8 | 6 | 0.7190 | R100 (clade A. caviae) | 12 | 3 | 0.9346 | − | 22 | 8 | 0.9159 | |

| gyrB (753 bp) | 21 | 7 | 1.0000 | − | 12 | 6 | 0.9346 | − | 35 | 12 | 0.9878 | |

| metG (504 bp) | 21 | 7 | 1.0000 | − | 10 | 8 | 0.8954 | − | 33 | 12 | 0.9805 | |

| ppsA (537 bp) | 21 | 14 | 1.0000 | − | 12 | 11 | 0.9346 | − | 35 | 19 | 0.9878 | |

| radA (405 bp) | 20 | 12 | 0.9952 | AK202 (clade B) | 10 | 3 | 0.9150 | − | 32 | 14 | 0.9829 | |

| recA (598 bp) | 19 | 7 | 0.9905 | − | 10 | 6 | 0.9216 | LL4.4-18D (clade A) | 31 | 11 | 0.9829 | |

| rpoB (426 bp) | 16 | 3 | 0.9667 | − | 8 | 4 | 0.8301 | − | 23 | 6 | 0.9415 | |

| rpoD (503 bp) | 19 | 8 | 0.9905 | − | 11 | 5 | 0.9085 | − | 32 | 12 | 0.9805 | |

| tsf (686 bp) | 14 | 4 | 0.9381 | AK202, BVH17 (clade B) | 9 | 4 | 0.8889 | RT10-17Ga* (clade A) | 24 | 7 | 0.9512 | |

| zipA (423-438 bp) | 19 | 29 | 0.9905 | ADV137a (clade A. popoffii/ A.bestiarum/ A. piscicola); CCM 4242 (clade A. veronii) | 12 | 22 | 0.9477 | LL4.4-18D*, AK207*, AK211* (clade A); CECT 4232T (clade A. enteropelogenes) | 33 | 34 | 0.9878 | |

| Clonal-Frame analysis | Mutation events† | 55 | 3 | 9 | ||||||||

| Recombination events† | 10 | 33 | 56 | |||||||||

| Substitutions introduced by recombination† | 95 | 126 | 216 | |||||||||

| No of sites without recombination† | 7364 (83.1% of the sequence length) | 2880 (32.5% of the sequence length) | 1744 (19.7% of the sequence length) | |||||||||

| ρ/θ‡ | 0.097 (0.094–0.099) | 9.4 (9.4–9.4) | 6.5 (6.5–6.5) | |||||||||

| r/m‡ | 0.89 (0.87–0.90) | 37 (36–40) | 23 (23–24) | |||||||||

ρ/θ, relative rate of recombination and mutation;

r/m, relative effect of recombination and mutation;

Phylogenetic discrepancy without horizontal gene transfer event detected by RDP software.

Measured between each isolate of each lineage (or the whole population) and their most recent common ancestor.

The numbers in brackets are 95% confidence intervals.

Recombination rate and horizontal gene transfer in Media SC

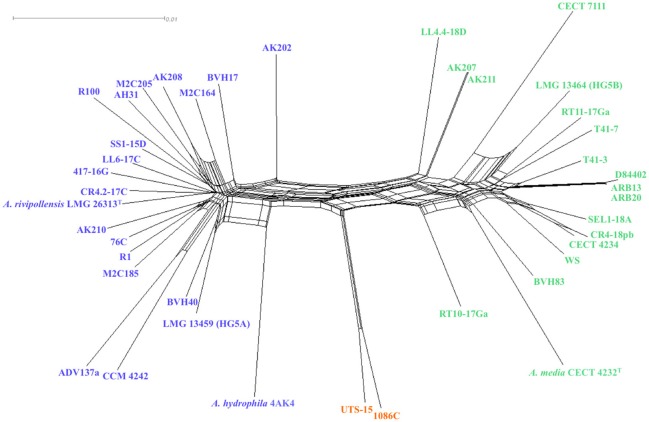

Homoplasy index φW test showed evidence for recombination between clades and within every clade (P-value < 0.0001), as confirmed by the interconnected network generated by the Neighbor-Net analysis (Figure 2). However, the network showed clusters congruent with the 3 clades defined in MLP confirming that recombination events were not frequent enough to blur the phylogenetic signal, and that recombination events were more frequent within clades.

Figure 2.

Neighbor-networks graph based on the concatenated sequences of the 16 housekeeping gene fragments (8,865 nucleotides), showing putative recombination events between 41 strains affiliated to Media species complex. A network-like graph indicates recombination events.

Differences in relative branching order among trees reconstructed by HK SLP were observed for 7 strains belonging to clade B and 3 strains of clade A (P-value = 0.2) (Table 2). These phylogenetic discrepancies occurred in 6 out of the 16 SLP trees, and this suggested occurrence of HGT events (Table 2) that were further studied by RDP analysis. Twenty-six strains (8 out of the 21 clade A strains and all clades B strains) were detected by RDP for potential recombinant sequences that resulted from at least 16 HGT events spanning from one to three genes. All genes were affected by HGT events, with the exception of atpD, groL, and gyrB loci. Most strains were affected by one or two events (12 and 9 strains, respectively). Nine events could not be linked to parental sequences, suggesting that transfers occurred from strains that are not represented in our collection.

The IsA values (0.222, Table 2) supported that Media SC displays an overall clonal population structure. However, it appeared that IsA values associated with clades A and B were highly heterogenic (0.019 and 0.310, respectively, Table 2), and this suggested different trends of population structure without any possibility to draw a clear conclusion, possibly because the scores for the mean genetic diversity for the total population and inside each clade were high (H > 0.9, Table 2). Meanwhile, the ClonalFrame analysis, an approach that takes into account the nucleotide sequences and not only the allelic profiles, showed that the number of recombination events detected between isolates of each lineage and their most recent common ancestor was higher in the clade B than in clade A (33 vs. 10, respectively). There were fewer sites involved in recombination events in lineage A than in lineage B (16.9 vs. 67.5%, respectively) (Table 2). The relative effect of mutation and recombination (r/m) was evaluated to 23 (CI95%: 23–24) for the Media SC (Table 2), but the r/m ratio was of 37 (CI95%: 36–40) and of 0.89 (CI95%: 0.87–0.90) for lineages B and A, respectively. This showed that recombination is more likely involved in the emergence of clade B than mutation while the two mechanisms of evolution were equally involved in the emergence of clade A.

Ribosomal multi operon diversity in Media SC

The intraclade rrs sequence similarity, ranging from 98.7 to 100%, did not exceed the interclade similarity (98.9–100%) and no sequence signature was found (Supplementary Taxonomic Sheet; and Supplementary Table 2). This supported that rrs sequencing within Media SC lacked of discrimination power. The SLP tree based on almost complete 16S rRNA gene (rrs) sequences (1,322 bp) confirmed that ribosomal phylogeny did not robustly discriminate strains from the 3 Media SC MLP clades, as generally observed for other closely related species in the genus Aeromonas (Supplementary Figure 1). In addition, major incongruences were observed between HK MLP and rrs phylogeny (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1).

Independently to the clade, 7 to 11 copies of rrs were found in the Media SC strains (Figure 1), and this high number of copies represents a potential diversity marker. Chromatogram analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed that there were microheterogeneities between rrs copies in a single strain (Supplementary Table 2). Sequence microheterogeneities were located within the V3 (457 to 464, and 469 to 476 position in rrs) and V6 (1,009 to 1,011, and 1,018 to 1,019 position in rrs) regions.

At the Media SC level, 27 different PCR-TTGE patterns revealing 14 different V3 sequences in rrs (1 to 5 distinct sequences per strain) were detected, and pattern diversity was more frequent in clade A (Supplementary Table 3). TTGE band 15 was present in all strains belonging to clades B and C while observed only for 3 strains belonging to clade A (P-value < 0.0001). TTGE band 21 was present in all but two strains belonging to clade A while present in 3 out of the 16 strains belonging to clade B and absent from clade C strains (P-value < 0.0001) (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 3).

The rrs distribution along the chromosome also varied with 33 different I-CeuI PFGE patterns observed in the studied population. A 400-kb I-CeuI fragment was more frequently observed for strains belonging to clades A and C (74% and 100%, respectively) than for those of clade B (7%) (Figure 1; P-value = 0.0002). Clustering obtained according to rrn distribution was congruent with MLP clades (Adjusted Wallace Coefficient = 1.00, CI95%: 1.00-1.00), while congruence was lower between V3 PCR-TTGE profiles and MLP clades (Adjusted Wallace Coefficient = 0.64, CI95%: 0.26–1.00).

Altogether, strains belonging to clades A, B, and C were distinguished by the number and distribution of rrs in the chromosome combined or not with V3 heterogeneity. Even if rrs sequences were weak phylogenetic markers, ribosomal skeleton and rrs copy repertoire were traits related to clade emergence in Media SC.

Comparative genomics in Media SC

The genomes from 14 Media SC strains (5, 7, and 2 strains affiliated to the clade A, B and C, respectively) were compared. For strains belonging to the same clade, the genomic metrics ANI and isDDH values were ≥95.3% and ≥65.1%, respectively, while values ≤ 94.6% and ≤ 61.2% were observed between clades, respectively (Table 3). According to the current rules in taxonomy, the genome metrics affiliated the 3 clades to 3 genomospecies, two of them being already described as taxonomic species, A. media and A. rivipollensis. The clade/genomospecies “C” was proposed herein as Aeromonas sp. genomospecies paramedia awaiting further studies for taxonomic species description.

Table 3.

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and in silico DNA-DNA Hybridization (isDDH) for strains belonging to the Media complex.

| Clade | Strain | G + C content | A | B | C | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |||

| A | 1- A. caviae LMG 13459 | 61.7% | 79.2 | 73.2 | 77.4 | 68.0 | 53.7 | 56.6 | 54.3 | 53.6 | 54.1 | 52.9 | 52.9 | 60.6 | 60.1 | |

| 2- BVH40 | 61.4% | 97.2 | 74.1 | 78.4 | 68.2 | 54.1 | 56.9 | 54.6 | 54.2 | 54.6 | 53.0 | 53.0 | 61.2 | 61.1 | ||

| 3- AK202 | 61.3% | 96.4 | 96.5 | 73.6 | 65.1 | 57.4 | 60.5 | 57.8 | 57.0 | 57.5 | 56.5 | 56.5 | 60.0 | 60.5 | ||

| 4- A. media 76C | 61.3% | 97.0 | 97.1 | 96.5 | 67.5 | 54.5 | 57.2 | 55.2 | 54.2 | 54.9 | 53.3 | 53.3 | 60.5 | 60.2 | ||

| 5- A. hydrophila 4AK4 | 62.0% | 95.8 | 95.8 | 95.3 | 95.7 | 53.7 | 55.3 | 53.9 | 53.2 | 54.0 | 53.3 | 53.3 | 61.0 | 60.6 | ||

| B | 6- A. caviae LMG 13464 | 61.3% | 93.2 | 93.2 | 93.9 | 93.3 | 93.1 | 74.9 | 78.9 | 80.3 | 79.6 | 78.8 | 78.7 | 57.2 | 57.0 | |

| 7- AK211 | 61.1% | 93.7 | 93.8 | 94.5 | 93.9 | 93.5 | 96.7 | 74.9 | 74.9 | 76.7 | 74.7 | 74.6 | 57.9 | 57.5 | ||

| 8- A. media CECT 4232T | 61.1% | 93.2 | 93.3 | 93.9 | 93.4 | 93.1 | 97.2 | 96.6 | 77.9 | 83.8 | 79.2 | 79.2 | 57.5 | 57.0 | ||

| 9- Aeromonas sp. CECT 7111 | 61.6% | 93.1 | 93.2 | 93.8 | 93.2 | 93.1 | 97.4 | 96.7 | 97.1 | 78.6 | 78.5 | 78.5 | 57.0 | 56.8 | ||

| 10- A. media WS | 60.7% | 93.2 | 93.2 | 94.0 | 93.3 | 93.2 | 97.2 | 96.8 | 97.7 | 97.2 | 79.5 | 79.4 | 57.4 | 57.2 | ||

| 11– A. media ARB13 | 61.0% | 92.9 | 93.0 | 93.7 | 93.0 | 93.1 | 97.2 | 96.7 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.1 | 100.0 | 57.4 | 56.8 | ||

| 12– A. media ARB20 | 61.0% | 93.0 | 93.0 | 93.7 | 93.0 | 93.1 | 97.2 | 96.7 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.1 | 100.0 | 57.3 | 56.7 | ||

| C | 13- 1086C | 62.2% | 94.5 | 94.6 | 94.3 | 94.4 | 94.6 | 93.9 | 94.0 | 93.9 | 93.8 | 93.9 | 93.9 | 93.9 | 81.9 | |

| 14- A. eucrenophila UTS 15 | 61.8% | 94.4 | 94.6 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.5 | 93.8 | 93.9 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.7 | 93.8 | 97.5 | ||

ANI values are displayed in bold in the lower triangle and isDDH values in the upper triangle. The isDDH values displayed are the upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals. Guanine + cytosine content is indicated for each genome (G + C content %).

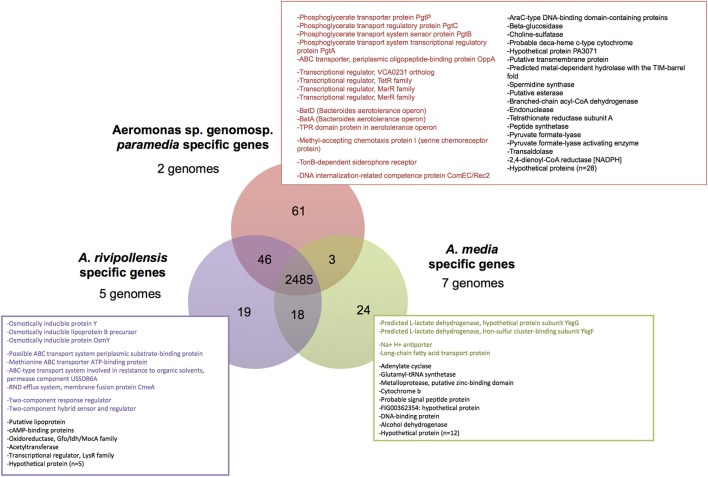

The pangenome of Media SC was estimated in 7,867 genes, the core-genome in 2,485 genes, the softcore-genome in 3,026 genes, the shell-genome in 1,395 and the cloud-genome in 3,446 genes. The clade-specific genome was analyzed within Media SC. It corresponded to the core-genome of each clade that was not shared with any of the two other clades (Figure 3). Nineteen genes were specific to A. rivipollensis genomes (Figure 3) especially genes involved in environmental adaptation, including osmotically inducible proteins (n = 3), transport systems (n = 4) and two-component system proteins (n = 2). However, the sole phenotype related to osmoregulation tested herein, the tolerance to NaCl, did not differ between A. media and A. rivipollensis (Supplementary Taxonomic Sheet). The A. media clade-specific genome was composed of 24 genes (Figure 3), among which two subunits of a predicted L-lactate dehydrogenase, two proteins of transport systems and a majority of CDS (Coding DNA Sequences) with unknown function. Phenotypically, the ability to utilize DL-lactate also differentiated A. media (clade B) (Figure 1). The specific genome of the genomospecies paramedia (clade C) was larger but this was probably due to the comparison of only 2 clade C genomes and should be confirmed on a larger panel of genomes. About half genes (n = 29) were annotated as hypothetical proteins in this clade. Among the 32 other genes, half were involved in adaptation to environment or to environment changes: transporters (n = 5), transcriptional regulators (n = 4), aerotolerance (n = 3), chemotaxis (n = 1), iron uptake (n = 1), and competence (n = 1).

Figure 3.

Venn diagram representing the core-genome of Media species complex and lineage conserved core-genome. The conserved specific genes are indicated for each lineages, and genes likely associated to environmental adaptation and/or change are colored.

Finally, the core-genome of Media SC represented 30% of its pan-genome in our study. The clade specific-genomes contained both housekeeping and adaptive genes suggesting that speciation within Media SC could be driven by positive selection related to environment conditions.

In silico delineation of habitats and lifestyles within Media SC

Considering previous genomic data, habitat and lifestyle within Media SC could be questioned, mainly for A. media and A. rivipollensis. Among 113 gyrB sequences retrieved from databases, 85 included the region that we amplified from our collection (positions 298–644). In this region, three specific positions (508, 609, and 627) unambiguously differentiated A. rivipollensis, A. media and Aeromonas sp. genomospecies paramedia and they were used to likely assign the 85 aligned sequences to a clade: 54 were assigned to A. rivipollensis and 29 to A. media. Together with the strains studied herein (Table 1), the two species were equally recovered from a majority of environmental sources, mostly corresponding to wastewater (29 vs. 34%, P-value = 0.7), and soil and river sediments (3 vs. 4%, P-value = 0.6). Considering animal sources, we did not observe any difference in the type of host between the species A. rivipollensis and A. media although data are obviously limited by a low power: fishes (24 vs. 13%, P-value = 0.2) and other aquatic inhabitants, e.g., copepods, mussels, crabs and oysters (7 vs. 2%, P-value = 0.4), snails (both 4%) and goats (1 vs. 2%, P-value = 1.0). The exceptions were strains isolated from pigs that were affiliated to A. rivipollensis (16%) only. In addition, there was a trend for a higher prevalence of A. rivipollensis in marine or estuarine habitat than the one of A. media (15 vs. 6%, P-value = 0.076).

The human isolates of A. rivipollensis and A. media were both found in disease context (both 2%) or during an asymptomatic carriage (2 vs. 4%, P-value = 0.6) (Table 1). Despite similar habitats, A. rivipollensis strains were more frequently associated with animal or human hosts (44/75) compared with A. media strains (13/47) (P-value = 0.002).

Discussion

Evolution mode in aeromonads and Media SC

Bacterial evolution is a major criterion for taxonomy because 16S rRNA (rrs) gene-based phylotaxonomy has become since 3 decades a major standard for species delineation and description. Alternative markers are increasingly used when 16S rRNA gene is not enough informative for robust phylogeny. This is particularly the case for bacteria organized in species complex such as Ralstonia (Li et al., 2016), Burkholderia cepacia (Vandamme and Dawyndt, 2011), Acinetobacter baumanii (Cosgaya et al., 2016). Alternative markers are genes encoding housekeeping proteins frequently associated in MLP studies (Roger et al., 2012b) that also allow population structure studies. The use of MLP is recommended in aeromonads taxonomy because 16S rRNA gene is considered of low value for classification of closely related Aeromonas spp. in the genus (Martinez-Murcia et al., 1992, 2011). Reasons are both the low rrs diversity among related species and the heterogeneity among rrs copies in a single species that may surpass the interspecies sequence divergence (Alperi et al., 2008; Roger et al., 2012b; Lorén et al., 2014). Finally, new recommended taxonomy approaches proposed by Chun and Rainey (2014) that consist in analyzing complete genomes with a polyphasic approach, have been applied to Media SC.

For the Media SC, the use of the sequences of 16 concatenated genes improved the robustness of the phylogeny compared to 7-gene based tree and single gene based trees (Roger et al., 2012a). This confirms that large amount of genetic information may be needed to robustly detect a phylogenetic signal in the genus (Colston et al., 2014), particularly when species are closely related. The use of 16 housekeeping genes gives ML trees congruent with core genome-based phylogeny (Colston et al., 2014) confirming that 16 gene-based MLP is an efficient tool to delineate clades among aeromonads. Moreover, 16 gene-based MLP was congruent with genome metrics determination (ANI and isDDH). For the genus Aeromonas a good agreement between MLP and DDH (Figueras et al., 2011; Martinez-Murcia et al., 2011) and between MLP, isDDH, and ANI (Colston et al., 2014) have been reported. Comparison of MLP tree structure and genome metrics thresholds gives the status of taxonomic species to clades and lineages. In this study, it supported the delineation of A. rivipollensis and A. media as independent species but also conferred the status of genomospecies to clade C. A temporary non-validated denomination is proposed for the third genomospecies, Aeromonas sp. genomospecies paramedia, in order stimulate comparison with members of this group in future taxonomic descriptions or reappraisals. Aeromonas sp. genomospecies paramedia should not be considered as a new species on the basis of the data provided herein and larger number of strains is awaited for a robust species description.

A previous study of temporal diversification suggested that Aeromonas has begun to diverge by mutation about 250 My ago and exhibited constant divergence and speciation rates through time and clades (Lorén et al., 2014). This divergence time is considered to be rather slow compared to E. coli/Salmonella spp. divergence (120 My). One hypothesis to explain slow speciation rates is that recombination events among members of species complexes could blur vertical lineage emergences. Recently, Huddleston et al. (2013) have established that natural transformation could be a mechanism for HGT between environmental Aeromonas strains, and have shown that the transformation groups roughly corresponded to phylogroups. In A. media SC, MLP showed that mutation signals were blurred by neither homoplasy nor HGT, but that genetic exchanges were linked to clade with higher frequency of recombination inside the clades of Media SC. However, it is noteworthy that A. media and A. rivipollensis differed clearly by their r/m. The emergence of the A. media lineage is more influenced by recombination events than A. rivipollensis. The speciation in bacterial population could be influenced by differing modes of evolution involved in lineage emergence (Vos and Didelot, 2009), as observed for A. media and A. rivipollensis. Given their importance in the speciation process (Lassalle et al., 2015), difference in evolution mode between two closely related bacterial populations could be used as a complementary character for new species delineation in an approach of integrative taxonomy (Teyssier et al., 2003; Alauzet et al., 2014).

Despite the development of alternative markers and phylogenomics, ribosomal operons (rrn) containing 16S rRNA gene (rrs) remain major landmarks of chromosomal structure and bacterial evolution. Indeed, conservation of rrn sequence and copy number that protect protein synthesis from major variations appears as a quasi-general rule in the bacterial world. The meaning of the high number and heterogeneity of rrs copies in aeromonads remains unknown but there is no doubt that such a diversity in rrn content should be linked to particular evolution processes, such as genome dynamics (Teyssier et al., 2003). In E. coli mutants, the rrn copy number has been experimentally related to living capacities in diverse conditions (Gyorfy et al., 2015). Differences in sequence between copies are less studied but it has been proposed for vibrios and aeromonads (Jensen et al., 2009; Roger et al., 2012a) that sequence variations among rrn repertory may achieve fine-tuning of the ribosome function. This could maintain functional diversity and thereby could optimize bacterial adaptation in unstable conditions. RIMOD analysis suggested there was either diversification from ancestral conserved type 21 rrs sequence in A. rivipollensis and type 15 in A. media or, contrarily, differential homogenization of copies by concerted evolution in each species (Liao, 2000; Teyssier et al., 2003). The latter hypothesis fits with the adaptation to more stable ecological conditions and therefore with a speciation process in adequacy to the ecotype concept of species. Facing the lack of diversity of rrs bulk sequences (mixing sequences of the different copies) in aeromonads, the combined diversity in rrs copy number and sequence, so-called RIMOD, is an interesting marker (Roger et al., 2012b). Since RIMOD, MLP, and ANI showed congruent grouping of strains, an involvement of rrn dynamics in A. media speciation could be suggested. Finally, our results underline that 16S rRNA genes deserve to be studied in aeromonads taxonomy not by phylogeny approach based on bulk sequences but rather by approaches such as RIMOD that takes into account the diversity in number and in sequence of every copy.

Insights about speciation processes in a population can also be provided by MLP and genomics. The chaperone protein DnaJ participates actively to the response to hyperosmotic and/or heat shocks in a DnaK-independent pathway (Caplan et al., 1993). Among the Media SC population (41 isolates), a 3-amino acid deletion in the sequence of protein DnaJ was detected in 95% (n = 20) of the strains belonging to A. rivipollensis and in 17% (n = 3) to A. media, while absent from all the strains belonging to other species of the genus. Genomics data from 14 genomes showed that 3 genes presumed to be associated to the osmotic stress response were specific to A. rivipollensis genome that potentially acquired them by HGT from Betaproteobacteria. Although the absence of homologs does not mean that the function is absent in A. media, one scenario suggested by these results is that the type of response to hyperosmotic stress in particular niches could be involved in the speciation of A. rivipollensis. We cannot exclude that similar role of positive selection by environmental conditions could be suspected from the annotation of the specific genome of each Media SC clades. In fact, most CDS are annotated as “hypothetical proteins” or as protein involved in adaptation to environment and environment changes such as transporters or transcriptional regulators, but this assessment requires further studies.

With the exception of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida that is considered as a specialized fish pathogen (Dallaire-Dufresne et al., 2014) and that present genomic characteristics associated with host adaptation such as gene decay (Reith et al., 2008), habitat and lifestyle have been hardly related to population structure and genomics in the genus Aeromonas (Roger et al., 2012a). Overall, the speciation by emergence of genomically differentiated populations without specialized lifestyle, as observed in this study, argues for a versatile behavior. Speciation within the Media SC might be mainly driven by general environmental changes such as chemical and physical conditions rather than by adaptation to a particular host. In this study, water and sediments likely appear as primary habitats whereas association with aquatic organisms and vertebrate gut could be an opportunistic lifestyle, sometimes involved in infectious processes.

Toward integrative and population-based delineation of bacterial species

We proposed herein a comprehensive population study of bacteria affiliated to the species A. media (Allen et al., 1983) and to A. rivipollensis (Marti and Balcázar, 2015), two species that were initially defined on the basis of 15 A. media strains isolated around the same trout farm and 2 A. rivipollensis isolated in the same Spanish river. Several characteristics determined at the time of the species description have been described more precisely herein on a larger panel of strains from diverse habitats. A. media should be now considered as motile and A. media and A. rivipollensis as rare brown pigment producers. The motility and production of pigment were the only phenotypic characters used to differentiate A. rivipollensis from A. media by Marti and Balcázar (2015) when pigment production is only a typical reaction of the type strain of A. media but not of the other strains. The recent description of A. rivipollensis is emblematic of the taxonomic pitfalls of considering a limited number of isolates and of considering strains of the closely recognized species limited to the sole type strain for novel species characterization. Therefore, an emendation of A. media and A. rivipollensis description is necessary and proposed below.

This argues for further strengthening the taxonomic recommendations toward a population-based taxonomy. The number of strains included in a taxonomic description is not a sufficient criterion for robust species description; the representativeness of the population should also be taken into account, as advised by Christensen et al. (2001) and as detailed in the Report of the ad hoc committee for the re-evaluation of the species definition in bacteriology (Stackebrandt et al., 2002). Although representativeness may sometimes be complex to achieve because it is difficult to know the population and its habitats at the stage of species description, redundancy should be strictly fought and diversity actively sought. The strains studied herein covered the known lifestyle diversity of strains affiliated to Media SC as confirmed by databank survey.

Polyphasic approach is recommended since a long time for bacterial taxonomy (e.g., Colwell, 1970; Figueras et al., 2011). However, the current bacterial taxonomy remains mainly numerical and phenetic, even if the reconstruction of a phylogenetic tree containing the new taxon is generally required for species description. The phylogenetic tree is mainly used to easily visualize the relationships between the new taxon and known taxa rather than for true evolutionary analyses. Multi-locus genetics and genomics generate large amount of data that should be used for a more integrative purpose, i.e., integration of population biology and evolutionary disciplines into taxonomy (Padial et al., 2010), in order to circumscribe a population that gains the rank of species in its biological and evolutionary dimensions in addition to the barcoding that defines its taxonomic frame. Therefore, integrative taxonomy will provide advances for the definition of species or other significant units in the domain Bacteria, particularly by providing data about genomic (Chun and Rainey, 2014) and/or ecological speciation (Lassalle et al., 2015) beside numerical definition of taxa. This is particularly true for genera in which the species are closely related or organized in complexes of species, i.e., groups of species with unclear boundaries as observed for Aeromonas, Vibrio, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, and several enterobacterial genera.

Emended description of Aeromonas rivipollensis, Marti and Balcazar 2016

The description is as done by Marti and Balcázar (2015) with the exceptions that strains are able to growth at 4°C, and the growth is variable at 3% NaCl but not at 5% NaCl. Strains do not use citrate. Hydrolysis of gelatin is variable. Acid is produced by fermentation from L-arabinose. Acid production from lactose or amygdalin is variable.

In addition, strains are motile but do not swarm. No hemolysis is observed on sheep blood agar at 35°C. Acid is produced by fermentation from D-mannose, D-cellobiose. The strains are negative for production of butanediol, DL-lactate and gas from glucose. Strains are susceptible to cefoxitin.

The key phenotypic characters that differentiate the species from the close relative A. media are the absence of DL-lactate utilization and cefoxitin susceptibility. For routine identification purpose, when genomics data are unavailable, gyrB combined with radA sequencing is efficient to separate A. rivipollensis from A. media and from others genomospecies in the genus.

Emended description of Aeromonas media Allen et al. 1983

The description is as done by Allen et al. (1983) with the exceptions that swimming motility is observed and that diffusible brown, non-fluorescent pigment produced by the type strain is rarely produced by other strains. In addition, growth occurs variably in 3% (wt./vol.) sodium chloride, variable response is observed for arginine dihydrolase, and strains utilize sucrose as sole carbon sources for energy and growth. Strains are resistant to cefoxitin.

The species can be differentiated from close relatives by the DL-lactate utilization and resistance to cefoxitin. For routine identification purpose, when genomic data are unavailable, gyrB combined with radA sequencing is efficient to separate A. media from A. rivipollensis and from others genomospecies in the genus. Compared to A. rivipollensis, A. media harbors a specific combination of three genes presumed to be associated to DL-lactate utilization (L-lactate permease, L-lactate dehydrogenase and D-lactate dehydrogenase).

The DNA G+C content of the type strain, determined from the genome sequences, was 61.3%, close to the rate of the original description obtained by denaturation experiments, which was 62.3 ± 0.2%.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the study: BL, HM, and EJ; Designed and performed the acquisition of clinical isolate and environmental collection: BL, MF, and FP; Performed the microbial analyses: ET, JK, FR, and FL; Performed acquisition and analyses of whole genome data: SC, ET, and JG; Analyzed and interpreted the data: ET, FR, JK, HM, EJ, and BL (microbial data), ET, SC (WGS); Discussed the taxonomical considerations: ET, BL, MF, HM, and EJ; Drafted the paper: ET, EJ, and BL; Critically revised the manuscript: HM, JG, MF, SC, FP, and FR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Association des Biologistes de l'Ouest, the Association pour la recherche et le développement en microbiologie et pharmacie (ADEREMPHA), and NIH RO1 GM095390 USDA and ARS agreement 58-1930-4-002 to JG, and by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation: AGL2011-30461-C02-02 and JPIW2013-095-CO3 to MF. The authors thank Matthew Fullmer for excellent technical assistance, Angeli Kodjo (VetAgro Sup, Marcy-L'Etoile) for having kindly provided some strains, and the ColBVH network (Collège de bactériologie, virologie et hygiène des hôpitaux généraux) for having provided strains.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00621/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alauzet C., Marchandin H., Courtin P., Mory F., Lemée L., Pons J.-L., et al. (2014). Multilocus analysis reveals diversity in the genus Tissierella: description of Tissierella carlieri sp. nov. in the new class Tissierellia classis nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 37, 23–34. 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D. A., Austin B., Colwell R. R. (1983). Aeromonas media, a New Species Isolated from River Water. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 33, 599–604. 10.1099/00207713-33-3-599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alperi A., Figueras M. J., Inza I., Martínez-Murcia A. J. (2008). Analysis of 16S rRNA gene mutations in a subset of Aeromonas strains and their impact in species delineation. Int. Microbiol. Off. J. Span. Soc. Microbiol. 11, 185–194. 10.2436/20.1501.01.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altwegg M., Steigerwalt A. G., Altwegg-Bissig R., Lüthy-Hottenstein J., Brenner D. J. (1990). Biochemical identification of Aeromonas genospecies isolated from humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28, 258–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaz-Hidalgo R., Alperi A., Buján N., Romalde J. L., Figueras M. J. (2010). Comparison of phenotypical and genetic identification of Aeromonas strains isolated from diseased fish. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 33, 149–153. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaz-Hidalgo R., Martínez-Murcia A., Figueras M. J. (2013). Reclassification of Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. dhakensis Huys et al. 2002 and Aeromonas aquariorum Martínez-Murcia et al. 2008 as Aeromonas dhakensis sp. nov. comb nov. and emendation of the species Aeromonas hydrophila. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 36, 171–176. 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruen T. C., Philippe H., Bryant D. (2006). A simple and robust statistical test for detecting the presence of recombination. Genetics 172, 2665–2681. 10.1534/genetics.105.048975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan A. J., Cyr D. M., Douglas M. G. (1993). Eukaryotic homologues of Escherichia coli dnaJ: a diverse protein family that functions with hsp70 stress proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 4, 555–563. 10.1091/mbc.4.6.555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier J.-P., Marchandin H., Jumas-Bilak E., Lorin V., Henry C., Carrière C., et al. (2002). Anaeroglobus geminatus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the family Veillonellaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52, 983–986. 10.1099/00207713-52-3-983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson J., Wagner T., Wilson T., Donachie L. (2001). Miniaturized tests for computer-assisted identification of motile Aeromonas species with an improved probability matrix. J. Appl. Microbiol. 90, 190–200. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai B., Wang H., Chen X. (2012). Draft genome sequence of high-melanin-yielding Aeromonas media strain WS. J. Bacteriol. 194, 6693–6694. 10.1128/JB.01807-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaillou S., Lucquin I., Najjari A., Zagorec M., Champomier-Vergès M.-C. (2013). Population genetics of Lactobacillus sakei reveals three lineages with distinct evolutionary histories. PLoS ONE 8:e73253. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H., Bisgaard M., Frederiksen W., Mutters R., Kuhnert P., Olsen J. E. (2001). Is characterization of a single isolate sufficient for valid publication of a new genus or species? Proposal to modify recommendation 30b of the Bacteriological Code (1990 Revision). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51, 2221–2225. 10.1099/00207713-51-6-2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J., Rainey F. A. (2014). Integrating genomics into the taxonomy and systematics of the Bacteria and Archaea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64, 316–324. 10.1099/ijs.0.054171-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colston S. M., Fullmer M. S., Beka L., Lamy B., Gogarten J. P., Graf J. (2014). Bioinformatic genome comparisons for taxonomic and phylogenetic assignments using Aeromonas as a test case. mBio 5:e02136-14. 10.1128/mBio.02136-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell R. R. (1970). Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus Vibrio: numerical taxonomy of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and related Vibrio species. J. Bacteriol. 104, 410–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Moreira B., Vinuesa P. (2013). GET_HOMOLOGUES, a versatile software package for scalable and robust microbial pangenome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7696–7701. 10.1128/AEM.02411-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgaya C., Marí-Almirall M., Van Assche A., Fernández-Orth D., Mosqueda N., Telli M., et al. (2016). Acinetobacter dijkshoorniae sp. nov., a member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex mainly recovered from clinical samples in different countries. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66, 4105–4111. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire-Dufresne S., Tanaka K. H., Trudel M. V., Lafaille A., Charette S. J. (2014). Virulence, genomic features, and plasticity of Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida, the causative agent of fish furunculosis. Vet. Microbiol. 169, 1–7. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X., Falush D. (2007). Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics 175, 1251–1266. 10.1534/genetics.106.063305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueira V., Vaz-Moreira I., Silva M., Manaia C. M. (2011). Diversity and antibiotic resistance of Aeromonas spp. in drinking and waste water treatment plants. Water Res. 45, 5599–5611. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueras M. J., Beaz-Hidalgo R. (2015). Aeromonas infections in humans, in Aeromonas, ed Graf J. (Norfolk: Caister Academic Press; ), 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Figueras M. J., Beaz-Hidalgo R., Collado L., Martínez-Murcia A. J. (2011). Recommendations for a new bacterial species description based on analyses of the unrelated genera Aeromonas and Arcobacter. Bull. BISMiS 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Jian J., Li W.-J., Yang Y.-C., Shen X.-W., Sun Z.-R., et al. (2013). Genomic study of polyhydroxyalkanoates producing Aeromonas hydrophila 4AK4. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 9099–9109. 10.1007/s00253-013-5189-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M., Guindon S., Gascuel O. (2010). SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 221–224. 10.1093/molbev/msp259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granum P. E., O'Sullivan K., Tomás J. M., Ormen O. (1998). Possible virulence factors of Aeromonas spp. from food and water. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 21, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorfy Z., Draskovits G., Vernyik V., Blattner F. F., Gaal T., Posfai G. (2015). Engineered ribosomal RNA operon copy-number variants of E. coli reveal the evolutionary trade-offs shaping rRNA operon number. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1783–1794. 10.1093/nar/gkv040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston J. R., Brokaw J. M., Zak J. C., Jeter R. M. (2013). Natural transformation as a mechanism of horizontal gene transfer among environmental Aeromonas species. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 36, 224–234. 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H., Bryant D. (2006). Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 254–267. 10.1093/molbev/msj030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S., Frost P., Torsvik V. L. (2009). The nonrandom microheterogeneity of 16S rRNA genes in Vibrio splendidus may reflect adaptation to versatile lifestyles. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 294, 207–215. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. T., Taylor W. R., Thornton J. M. (1992). The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. CABIOS 8, 275–282. 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenzaka T., Nakahara M., Higuchi S., Maeda K., Tani K. (2014). Draft genome sequences of amoeba-resistant Aeromonas spp. Isolated from aquatic environments. Genome Announc. 2:e01115-14. 10.1128/genomeA.01115-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küpfer M., Kuhnert P., Korczak B. M., Peduzzi R., Demarta A. (2006). Genetic relationships of Aeromonas strains inferred from 16S rRNA, gyrB and rpoB gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 2743–2751. 10.1099/ijs.0.63650-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganowska M., Kaznowski A. (2005). Polymorphism of Aeromonas spp. tRNA intergenic spacers. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 28, 222–229. 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle F., Muller D., Nesme X. (2015). Ecological speciation in bacteria: reverse ecology approaches reveal the adaptive part of bacterial cladogenesis. Res. Microbiol. 166, 729–741. 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Wang D., Yan J., Zhou J., Deng Y., Jiang Z., et al. (2016). Genomic analysis of phylotype I strain EP1 reveals substantial divergence from other strains in the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex. Front. Microbiol. 7:1719. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D. (2000). Gene conversion drives within genic sequences: concerted evolution of ribosomal RNA genes in bacteria and archaea. J. Mol. Evol. 51, 305–317. 10.1007/s002390010093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorén J. G., Farfán M., Fusté M. C. (2014). Molecular phylogenetics and temporal diversification in the genus Aeromonas based on the sequences of five housekeeping genes. PLoS ONE 9:e88805. 10.1371/journal.pone.0088805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti E., Balcázar J. L. (2015). Aeromonas rivipollensis sp. nov., a novel species isolated from aquatic samples. J. Basic Microbiol. 55, 1435–1439. 10.1002/jobm.201500264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. P., Lemey P., Lott M., Moulton V., Posada D., Lefeuvre P. (2010). RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics 26, 2462–2463. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Carnahan A., Joseph S. W. (2005). Family I. Aeromonadaceae in Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, eds Brennan D. J., Krieg N. R., Staley J. T., Garrity G. N. (New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; ), 556–578. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Murcia A. J., Benlloch S., Collins M. D. (1992). Phylogenetic interrelationships of members of the genera Aeromonas and Plesiomonas as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing: lack of congruence with results of DNA-DNA hybridizations. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42, 412–421. 10.1099/00207713-42-3-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Murcia A. J., Monera A., Saavedra M. J., Oncina R., Lopez-Alvarez M., Lara E., et al. (2011). Multilocus phylogenetic analysis of the genus Aeromonas. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 34, 189–199. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino M. E., Fasolato L., Montemurro F., Rosteghin M., Manfrin A., Patarnello T., et al. (2011). Determination of microbial diversity of Aeromonas strains on the basis of multilocus sequence typing, phenotype, and presence of putative virulence genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4986–5000. 10.1128/AEM.00708-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Kolthoff J. P., Auch A. F., Klenk H.-P., Göker M. (2013). Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 14:60. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miñana-Galbis D., Farfán M., Lorén J. G., Fusté M. C. (2002). Biochemical identification and numerical taxonomy of Aeromonas spp. isolated from environmental and clinical samples in Spain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93, 420–430. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser T., Talagrand-Reboul E., Colston S. M., Graf J., Figueras M. J., Jumas-Bilak E., et al. (2015). Exposure to pairs of Aeromonas strains enhances virulence in the Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Front. Microbiol. 6:1218. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren A., Garrity G. M. (2016). List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly published. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66, 1913–1915. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R., Olson R., Pusch G. D., Olsen G. J., Davis J. J., Disz T., et al. (2014). The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D206–214. 10.1093/nar/gkt1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pablos M., Rodríguez-Calleja J. M., Santos J. A., Otero A., García-López M.-L. (2009). Occurrence of motile Aeromonas in municipal drinking water and distribution of genes encoding virulence factors. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 135, 158–164. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padial J. M., Miralles A., De la Riva I., Vences M. (2010). The integrative future of taxonomy. Front. Zool. 7:16. 10.1186/1742-9994-7-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. L., Shaw J. G. (2011). Aeromonas spp. clinical microbiology and disease. J. Infect. 62, 109–118. 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picao R. C., Poirel L., Demarta A., Petrini O., Corvaglia A. R., Nordmann P. (2008). Expanded-Spectrum β-Lactamase PER-1 in an Environmental Aeromonas media Isolate from Switzerland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 3461–3462. 10.1128/AAC.00770-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoff M., Véron M. (1976). A taxonomic study of the Aeromonas hydrophila-Aeromonas punctata group. J. Gen. Microbiol. 94, 11–22. 10.1099/00221287-94-1-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith M. E., Singh R. K., Curtis B., Boyd J. M., Bouevitch A., Kimball J., et al. (2008). The genome of Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida A449: insights into the evolution of a fish pathogen. BMC Genomics 9:427. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P., Longden I., Bleasby A. (2000). EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 16, 276–277. 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M., Rosselló-Móra R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger F., Lamy B., Jumas-Bilak E., Kodjo A., colBVH study group. Marchandin H. (2012a). Ribosomal multi-operon diversity: an original perspective on the genus Aeromonas. PLoS ONE 7:e46268. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger F., Marchandin H., Jumas-Bilak E., Kodjo A., colBVH study group. Lamy B. (2012b). Multilocus genetics to reconstruct aeromonad evolution. BMC Microbiol. 12:62. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlácek I., Jaksl V., Prepechalová H. (1994). Identification of aeromonads from water sources. Epidemiol. Mikrobiol. Imunol. 43, 61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D. V. (2000). A putative heat-labile enterotoxin expressed by strains of Aeromonas media. J. Med. Microbiol. 49, 685–689. 10.1099/0022-1317-49-8-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E., Frederiksen W., Garrity G. M., Grimont P. A. D., Kämpfer P., Maiden M. C. J., et al. (2002). Report of the ad hoc committee for the re-evaluation of the species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52, 1043–1047. 10.1099/00207713-52-3-1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssier C., Marchandin H., Siméon De Buochberg M., Ramuz M., Jumas-Bilak E. (2003). Atypical 16S rRNA gene copies in Ochrobactrum intermedium strains reveal a large genomic rearrangement by recombination between rrn copies. J. Bacteriol. 185, 2901–2909. 10.1128/JB.185.9.2901-2909.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme P., Dawyndt P. (2011). Classification and identification of the Burkholderia cepacia complex: past, present and future. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 34, 87–95. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos M., Didelot X. (2009). A comparison of homologous recombination rates in bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 3, 199–208. 10.1038/ismej.2008.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.