Highlights

-

•

Leydig cell tumor is a testicular tumor with a low incidence accounting for 1–3% of testicular neoplasms.

-

•

Only about 10% of them show malignant behavior in the form of metastatic disease.

-

•

When diagnosed and treated early, long-term favorable outcomes are seen even with its potential metastatic behavior.

Keywords: Testicular neoplasms, Leydig cell tumor, Inguinal orchiectomy, RPLND, Malignant behavior

Abstract

Introduction

Leydig cell tumor constitutes only about 1–3% of testicular neoplasms. There is apparently increased incidence in the last few years; one possible explanation for this phenomenon is the widespread use of ultrasound technology and the subsequent increased early detection of smaller lesions that have not been found in historical series.

Case presentation

We report a case of Leydig cell tumor of testis in a patient presenting with painless long standing slowly growing left scrotal mass who found to have intrapulmonary nodule and multiple enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes on staging work up. The mass was managed by radical orchiectomy. Pathological diagnosis was Leydig cell tumor.

Discussion

Orchiectomy is the accepted mode of treatment but follow-up every 3–6 months with physical examination, hormone assays, scrotal and abdominal ultrasonography, chest radiography, and CT scans is essential in such a case with a potential for malignant behavior.

Conclusion

Inguinal orchiectomy is the therapeutic decision of choice and long-term follow-up is necessary to exclude recurrence or metastasis. Cases which fall in the grey zone like ours need to be followed up carefully for metastasis instead of rushing into an early retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, with its potential risks and complications.

1. Introduction

The present work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [1].

Leydig cell tumor is a testicular tumor with a low incidence accounting for 1–3% of testicular neoplasms. It manifests in the preadolescent or in the older people. It is a non-germ cell tumor of the testis and is included in the group of specialized gonadal stromal neoplasms. The frequent clinical presentation is that of a testicular nodule with or without endocrine manifestations [2].

We report a case of Leydig cell tumor of testis in a patient presenting with painless long standing slowly growing left scrotal mass. Imaging showed a left testicular mass with multiple enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes and right single subcentimetric intrapulmonary nodule. This mass was managed by inguinal radical orchiectomy. Pathological diagnosis was Leydig cell tumor of the testis. Lymph nodes and pulmonary nodule were observed radiologically over 2 months with no interval changes. The case could not be labeled as benign or malignant and patient is on follow-up.

2. Case report

A 63-year-old noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) patient presented with a painless swelling in the left testis first noticed by the patient 10 years ago was slowly progressive painless, and started to grow rapidly in last year. He had a history of left testicular trauma at 2 years of age in a form of laceration injury to the left hemiscrotum with tunica albuginea rupture that was open repaired then. On physical examination the left testis was 9 × 7 × 5 cm in size and the right testis was normal. No other signs, including gynecomastia or swelling of superficial lymph nodes were observed. Scrotal ultrasonography revealed that the left testis was replaced completely by a lobulated heterogeneous mass with multiple foci of calcification measured 8.5 × 6.5 × 5 cm with significantly increased vascularity and a thickened left spermatic cord with grade 3 left varicocele.

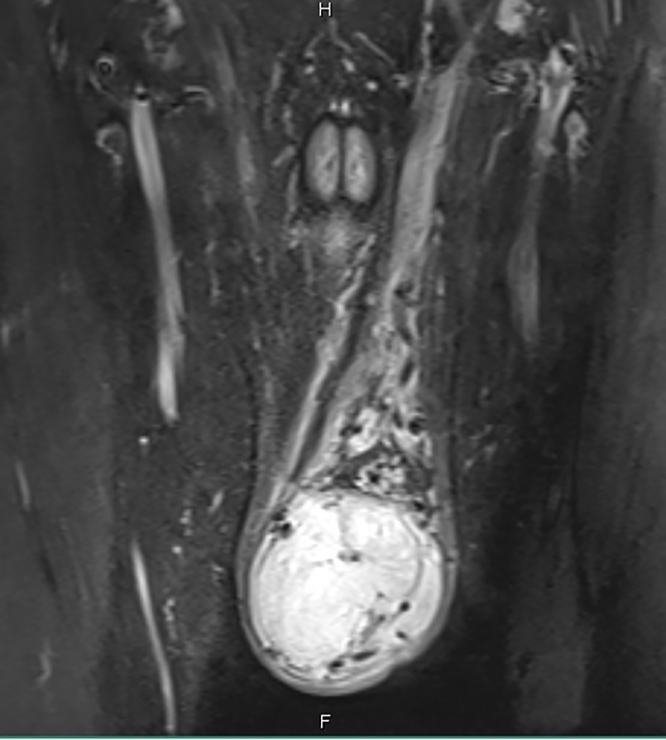

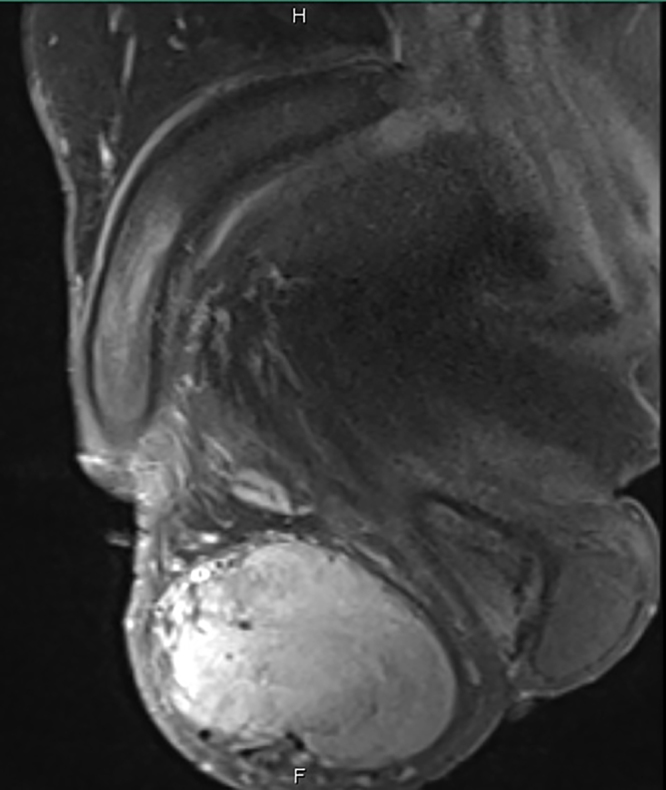

Pelvic MRI with contrast showed ill-defined left side lesion distorting the left testis that showed intense heterogeneous enhancement measuring 8.5 × 6 × 4 cm and thickened left spermatic cord (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 1.

Pelvic MRI with contrast, coronal view showing ill-defined left side lesion distorting the left testis that showed intense heterogeneous enhancement measuring 8.5 × 6 × 4 cm and thickened left spermatic cord.

Fig. 2.

Pelvic MRI with contrast, transverse view showing ill-defined left side lesion distorting the left testis that showed intense heterogeneous enhancement measuring 8.5 × 6 × 4 cm.

Fig. 3.

Pelvic MRI with contrast, sagittal view showing ill-defined left side lesion distorting the left testis that showed intense heterogeneous enhancement measuring 8.5 × 6 × 4 cm.

Spiral computerized tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, pelvis and scrotum showed a 0.7 cm right intrapulmonary nodule and a well-defined soft tissue density lesion 8.5 × 6.5 × 5 cm seen in left hemi-scrotum with prominent left spermatic cord and normal right testis with multiple enlarged paraaortic, interaortocaval and pericaval lymph nodes the largest was 1.2 cm in maximum short axis diameter (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Computed tomography prior to orchiectomy showing a retroperitoneal lymph node (arrow) measuring about 1.2 cm in maximum short axis diameter.

So radiologist impression at that time was a malignant infiltrative highly vascular tumor with possible spermatic cord involvement.

His routine investigations on admission such as hemogram, renal function tests, liver function tests and urinalysis were normal. Serum germ cell tumor-markers (LDH, alpha-fetoprotein and β -HCG) were normal and hormonal investigations were normal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tumor markers and hormonal evaluation at baseline, after surgery, and in the follow-up.

| Hormone/tumor marker | Normal Range for age | Pre-op | Post op/1 week | Post op/2months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone, total (ng/dL) | 270–1070 | 410 | 36 | 105 |

| LH (IU/L) | 0.8–12 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 25.2 |

| FSH (IU/L) | 0.1–11.6 | 1 | 8.3 | 22.7 |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 3.5–19.40 | 10.3 | 6.65 | 11.5 |

| PSA (ng/mL) | <4.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| LDH (U/L) | 240–480 | 369 | 328 | 330 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.9–8.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| β -HCG (IU/L) | <1.2 | <1.2 | <1.2 | <1.2 |

Abbreviations: LH luteinizing hormone, FSH follicle-stimulating hormone, PSA prostate specific antigen, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, AFP alpha-fetoprotein, β-hCG β-human chorionic gonadotropin. Normal ranges are according to hospital reference.

The patient underwent left high inguinal orchiectomy. And the specimen has been submitted for histopathological examination.

Pathology revealed a well circumscribed tumor mass weighing 211gm and measuring 6.5 × 5.5 × 3 cm, limited to the testis and epididymis without lymphovascular invasion, tumor invading tunica albuginea at some areas but not tunica vaginalis, no normal testicular tissue was identified. Small hard calcific foci and osseous metaplasia were also identified. Spermatic cord was 8 × 2 cm and uninvolved by the tumor (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10 ).

Fig. 5.

A well circumscribed, encapsulated mass measures 6.5 × 5.5 × 3 cm in size, the mass is easily separated from tunica vaginalis (arrow) (No infiltrative margins), step sectioning revealed homogenous yellowish cut surface. No necrosis identified.

Fig. 6.

Microscopic description. Section from tumor shows diffuse infiltrataion by medium to large polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders, round nuclei and prominent nucleoli along with rich vascular network and scant stroma. There is no evidence of necrosis, vascular invasion or increased mitotic activity.

Fig. 7.

Immunohistochemical stains. Calretinin, diffusely positive.

Fig. 8.

Immunohistochemical stains. Inhibin, diffusely positive.

Fig. 9.

Immunohistochemical stains. Melan A (MART-1), diffusely positive.

Fig. 10.

Immunohistochemical stains. Vimentin, diffusely positive.

3. Follow up

At follow-up patient was doing well. One week after orchiectomy testosterone steeply dropped to 36 ng/dL and luteinizing hormone (LH) started to rise from its lower limit of normal, then after 2 months testosterone raised to 105 ng/dL alongside with LH and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) rise to 25.2 and 22.7 IU/L respectively (Table 1).

The CT scan performed 2 months after orchiectomy showed no significant interval changes regarding lymph nodes or lung nodule (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Computed tomography 2 months post-orchiectomy showing the same retroperitoneal lymph node (arrow) measuring about 1.2 cm in maximum short axis diameter with no interval changes.

4. Discussion

Leydig cell tumor is the commonest tumor among non–germ cell neoplasms of the testis, accounting for 1–3% of testicular tumors in adults and 4% in prepubertal children. Only about 10% of them show malignant behavior in the form of metastatic disease, particularly to the lymph nodes, lung and liver. Malignant tumors occur exclusively in adults and are unaccompanied by endocrine changes [3], [4], [5], [6]. These tumors are most common in the third to sixth decade in adults, Another peak incidence is seen in children aged between 3 and 9 years. Only 3% of Leydig cell tumors are bilateral [7].

The histopathological findings for malignant leydig cell tumors include cytological atypia, increased mitotic activity, large size (>5 cm), older age, vascular invasion, increased MIB-1 expression, necrosis, infiltrative margins, extension beyond the testicular parenchyma and DNA aneuploidy [8], [9].

While differentiating between benign and malignant leydig cell tumors, the presence of metastasis is the most accepted criterion for malignancy. Metastases have been reported as long as 8 and 17 years later [10].

Patients either present with a painless enlarged testis or the tumor is found incidentally on US. In up to 80% of cases, hormonal disorders with high oestrogen and oestradiol levels, low testosterone, and increased levels of LH and FSH are reported [11], [12], while negative results are always obtained for the testicular germ cell tumor-markers AFP, HCG, LDH and PLAP. Up to 10% of adult patients present with gynaecomastia [12], [13]. The low testosterone level observed post op could be interpreted as the LH was suppressed by the tumor expression of testosterone to keep testosterone within normal range and so the right testis is suppressed and after orchiectomy it is recovering its function.

Some morphological features like larger tumor size (6.5 cm), extension beyond the testicular parenchyma into tunica albuginea favored a diagnosis of malignancy in addition to older age and the equivocal finding of regional lymph node metastasis and right lung nodule on the C.T scan. On the other hand increased mitotic activity was not identified and there was no lymphovascular invasion, necrosis, cytological atypia or extension beyond the capsule of the testis in addition 2 months after surgery the images showed no significant interval changes regarding lymph nodes or lung nodule and patient was doing well.

Orchiectomy is the accepted mode of treatment but follow-up every 3–6 months with physical examination, hormone assays, scrotal and abdominal ultrasonography, chest radiography, and CT scans is essential in such a case with a potential for malignant behavior.

When diagnosed and treated early, long-term favorable outcomes are seen even with its potential metastatic behavior. In stromal tumors with histological signs of malignancy, especially in older patients, orchiectomy and early retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy may be an option to prevent metastases [14] or to achieve long-term cure in stage IIA cases [15]. Prophylactic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) is unjustified for patients with clinical stage I disease without high-risk features [16]. Tumors that have metastasized to lymph nodes, lung, liver or bone respond poorly to chemotherapy or radiation and survival is poor [14]. There is no standard of therapy for management of metastatic leydig cell tumors and no recommendations are available for the treatment of these patients.

Without clinical signs of malignancy, an individualized surveillance strategy after orchiectomy is recommended in patients with one, or more, pathological features of malignancy. Follow-up is recommended in all high risk patients; every 3–6 months with physical examination, hormone assays, scrotal and abdominal ultrasonography, chest radiography, and CT scans [12].

Patient plan, is to follow him up every 3 months with physical examination, hormone assays, scrotal and abdominal ultrasonography for 3 years then yearly and 6 monthly with chest radiography and CT scans for the first 2 years then yearly for up to 5 years as no interval changes were noted on the CT scan performed 2 months after orchiectomy and to avoid radiation risk with recurrent images over the follow up period as metastases have been reported as long as 8 and 17 years later [10]. If subsequent images showed size increase RPLND would be considered.

No recommendations are available for the size criteria in interval change to be considered significant for growth of the known lung lesion and para-aortic lymphadenopathy, as with other germ cell tumors.

5. Conclusions

Leydig cell tumors are rare neoplasms arising from gonadal stroma. Knowledge of this certain but rare tumor entity is important as endocrine manifestations could be the only sign for the presence of these tumors and if diagnosed and treated early, long-term favorable outcomes are seen even with its potential metastatic behavior.

Inguinal orchiectomy is the therapeutic decision of choice and long-term follow-up is necessary to exclude recurrence or metastasis. Cases which fall in the grey zone like ours need to be followed up carefully for metastasis instead of rushing into an early RPLND with its potential risks and complications.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This is a report of a case; no research was conducted on patients that needed ethical approval.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Authors contribution

Muheilan Muheilan: Literature Review, Case presentation, surgical first assistant, submitting, corresponding and main author.

Maha Shomaf: Pathology part from diagnosis to literature review.

Emad Tarawneh: Radiology part from diagnosis to literature review.

Muayyad Murshidi: Imaging, literature review, Review of final manuscript.

Manar Al Sayyed: Pathology part from diagnosis to literature review.

Mujalli Murshidi: Main Surgeon, Performed Inguinal orchiectomy of the testicular mass and main attending for the patient.

Guarantors

Mujalli Murshidi and Muheilan Muheilan.

Contributor Information

Muheilan Mustafa Muheilan, Email: Mhelan87@hotmail.com.

Maha Shomaf, Email: mshomaf@ju.edu.jo.

Emad Tarawneh, Email: etarawneh@ju.edu.jo.

Muayyad Mujalli Murshidi, Email: muayyadmurshidi@icloud.com.

Manar Rizik Al-Sayyed, Email: dr.manar216@gmail.com.

Mujalli Mhailan Murshidi, Email: mujalli_mhailan@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tichoo S.K., Tamboli P., Warner N.E., Amin M.B. Testicular and paratesticular tumors. In: Weidner N., Cote R.J., Suster S., Weiss L.M., editors. Modern Surgical Pathology. Elsevier Science; Philadelphia: Saunders: 2003. pp. 1215–1256. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim I., Young R.H., Scully R.E. Leydig cell tumors of the testis: a clinicopathological analysis of 40 casesand review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1985;9:177–192. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson C.G., Ahmed A.A., Sesterhenn I. Enucleation for prepubertal Leydig cell tumor. J. Urol. 2006;176:703–705. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugimoto K., Matsumoto S., Nose K. A malignant Leydig cell tumor of the testis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2006;38:291–292. doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-6661-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal U., Sharma M., Bhatnagar D., Saxena S. Leydig cell tumor: an unusual presentation. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2009;52:395–396. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.55005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim I. Leydig cell tumors of the testis. A clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases and review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1985;9:177. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheville J.C. Leydig cell tumor of the testis: a clinicopathologic, DNA content, and MIB-1 comparison of nonmetastasizing and metastasizing tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1998;22:1361. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCluggage W.G. Cellular proliferation and nuclear ploidy assessments augment established prognostic factors in predicting malignancy in testicular Leydig cell tumors. Histopathology. 1998;33:361. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh Dr. Neha, Singh Chauhan Dr. Jitender. Leydig cell tumors of the testis: a case report. Int. J. Enhanc. Res. Med. Dent. Care. 2015;2(July (7)) ISSN: 2349–1590. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reznik Y. Luteinizing hormone regulation by sex steroids in men with germinal and Leydig cell tumors. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 1993;38:487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suardi N. Leydig cell tumor of the testis: presentation, therapy, long-term follow-up and the role of organ-sparing surgery in a single-institution experience. BJU Int. 2009;103:197. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozzini G. Long-term follow-up using testicle-sparing surgery for Leydig cell tumor. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 2013;11:321. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosharafa A.A. Does retroperitoneal lymph node dissection have a curative role for patients with sex cord-stromal testicular tumors? Cancer. 2003;98:753. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silberstein J.L. Clinical outcomes of local and metastatic testicular sex cord-stromal tumors. J. Urol. 2014;192:415. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Featherstone J.M. Sex cord stromal testicular tumors: a clinical series–uniformly stage I disease. J. Urol. 2009;181:2090. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]