Abstract

Background

The Japanese database of food amino acid composition was revised in 2010 after a 24-year interval. To examine the impact of the 2010 revision compared with that of the 1986 revision, we evaluated the validity and reliability of amino acid intakes assessed using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ).

Methods

A FFQ including 138 food items was compared with 7-day dietary records, completed during each distinct season, to assess validity and administered twice at approximately a 1-year interval, to assess reliability. We calculated amino acid intakes using a database that compensated for missing food items via the substitution method. Subjects were a subsample of two cohorts of the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. A total of 102 men and 113 women in Cohort I and 174 men and 176 women in Cohort II provided complete dietary records and the FFQ, of whom 101 men and 108 women of Cohort I and 143 men and 146 women of Cohort II completed the FFQ twice.

Results

In the comparison of the FFQ with dietary records, the medians (ranges) of energy-adjusted correlation coefficients for validity were 0.35 (0.25–0.43) among men and 0.29 (0.19–0.40) among women in Cohort I, and 0.37 (0.21–0.52) and 0.38 (0.24–0.59), respectively, in Cohort II. Values for reliability were 0.47 (0.42–0.52) among men and 0.43 (0.38–0.50) among women in Cohort I, and 0.59 (0.52–0.70) and 0.54 (0.45–0.61), respectively, in Cohort II.

Conclusions

The FFQ used in our prospective cohort study is a suitable tool for estimating amino acid intakes.

Keywords: Diet, Food frequency questionnaire, Amino acid intake, Validity, Reliability

Highlights

-

•

The Japanese database for food amino acid compositions was revised in 2010.

-

•

We evaluated the validity and reliability of amino acid intakes assessed via a FFQ.

-

•

The estimation via a new database had better validity than via the former database.

-

•

The estimation using the new database indicated good reliability.

Introduction

Studies assessing the association between dietary amino acids and cardiovascular disease risk have shown that dietary intake of cysteine was inversely associated with the risk of stroke in women.1 Higher methionine intake was associated with an increased risk of acute coronary events in men.2 Higher intake of animal protein, which is richer in methionine than vegetable protein, was also associated with an increased risk of ischemic heart disease in men, although vegetable protein had no effect.3 Furthermore, sulfur amino acids (SAA), including methionine and cysteine, changed lipid metabolism and influenced serum lipoprotein concentrations.4 Thus, the association between amino acids and cardiovascular disease has gained attention in recent years. It is necessary to examine the association between individual amino acid intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease in Japanese subjects because of limited evidence in this group.

In Japan, the amino acid composition of foods, based on the Standard Table of Food Composition, was re-issued in 2010 after an interval of 24 years.5 The updated version includes 337 food items, including 42 new items, and now shows protein as the sum of amino acid residues, total amino acids, ammonia, SAA as the sum of methionine and cysteine, and aromatic amino acids (AAA) as the sum of phenylalanine and tyrosine. Prior to publication of the revised table, Ishihara et al had developed a database using the previous amino acid composition table and evaluated the validity of a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) for estimating amino acid intake.6 However, the 2010 revision of the amino acid composition table of foods was substantial, so it is worthwhile to examine the validity and reliability of amino acid intakes based on this revision.

In the present study, we assessed the validity and reliability of amino acid assessment via a FFQ that was used in a large follow-up study of middle-aged Japanese men and women.

Methods

Validity and reliability study

The Japan Public Health Center-based prospective Study on Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases (JPHC Study) is a population-based prospective cohort study that included Cohort I in Ninohe, Yokote, Saku, and Chubu (formerly named Ishikawa) public health center (PHC) areas from 1990, and Cohort II in Mito, Nagaoka (formerly named Kashiwazaki), Chuo-higashi, Kamigoto, Miyako, and Suita PHC areas from 1993. A 5-year follow-up survey in Cohort I was conducted for residents who remained alive in 1995, and we estimated their nutrient intake using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ05).7 The same FFQ was used for the 5-year follow-up survey in Cohort II in 1998.

Subjects in the validity and reliability study were a subsample of participants in the JPHC Study Cohorts I and II. Details of the study protocol have been reported elsewhere.8, 9 In brief, the validity study of Cohort I was initiated in February 1994, and that of Cohort II was initiated in May 1996. Subjects for the validity analysis included participants who completed dietary records for 28 days (14 days for Chubu PHC area) and the FFQ for measuring the validity of FFQ05 (FFQv) among healthy volunteers with normal weight and without dietary restrictions. A total of 247 participants (122 men and 125 women) from four PHC areas in Cohort I and 392 participants (196 men and 196 women) from six PHC areas in Cohort II were recruited on a voluntary basis. For the reliability study, we analyzed data of participants who responded to the FFQ again at a 1-year interval, except in the Mito PHC area (9-month interval), for measuring the reliability of FFQ05 (FFQr) among the subjects in the validity analysis. The study was approved by the human ethics review committee of the National Cancer Center of Japan.

Dietary records

Dietary records were provided through 7 consecutive days on four separate occasions (a total of 28 days), in spring, summer, autumn, and winter, except for the Chubu PHC area, where a sub-tropical climate prevails. In that area, 7-day dietary records were collected only twice (winter and summer) because the seasonal variation was not expected to be large. Research dietitians instructed the subjects to use a specially designed booklet to record all foods and beverages prepared and consumed. Participants were asked to provide detailed descriptions of each food, including the methods of preparation and recipes whenever possible. The dietitians checked the records at subjects' homes, workplaces, or community centers during the survey and reviewed them in a standardized way.

Food frequency questionnaire in 5-year follow-up survey (FFQ05)

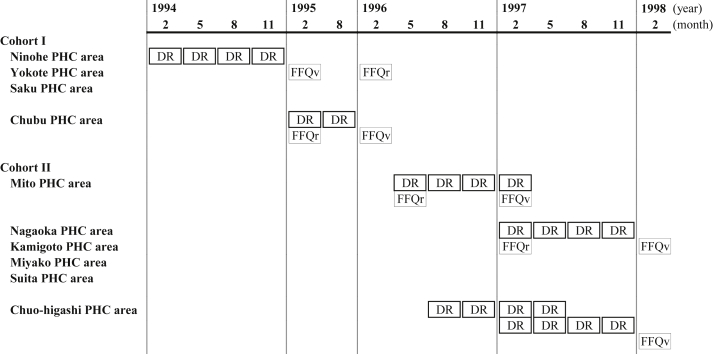

Both self-administered FFQ05s asked about the usual consumption of 138 food items during the previous year. Nine frequency and three portion size categories were used to obtain data on dietary habits. Frequency was recorded as almost never, 1–3 times per month, 1–2 times per week, 3–4 times per week, 5–6 times per week, once per day, 2–3 times per day, 4–6 times per day, and 7 or more times per day. Portion size was recorded as less than half, same, and more than one and a half times the specified amounts. One FFQ05 was used to assess the validity of the FFQ (i.e., FFQv) compared with dietary records (the gold standard of dietary assessment),10 and the other FFQ05 was used to assess the reliability of the FFQ (i.e., FFQr) with the FFQv. The sequence of data collection for the validity and reliability studies is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The sequence of data collection. DR, dietary record; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; PHC, Public Health Center.

Amino acid database of foods

The Amino Acid Composition of Foods in Japan 2010 shows 18 amino acids and some additional proteins.5 The table details 337 food items, including 133 items that were re-analyzed or newly added to the previous edition. Nevertheless, the revised amino acid composition covered only 18% of 1878 food items in the Standard Table of Food Composition in Japan 2010.11 Thus, we calculated amino acid intakes using the National Institute for Longevity Sciences Amino Acid Composition Table of Food (2010), which compensated for missing food items using the substitution method (e.g., using similar food or different parts of the same food) and contained 1745 food items (covering 93% of 1878 food items).12

Statistical analysis

The mean intakes of total protein and amino acids according to both the 28 days (14 days for Chubu PHC area) of dietary records and FFQ were calculated by sex and cohort group. Percentage differences were calculated using the following formula: difference in mean intake = (FFQ − dietary record)/dietary record. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between intakes according to the dietary record and the FFQ were calculated for crude values and energy-adjusted values. For the residual model, the mean daily consumption of energy was calculated using the Standardized Tables of Food Composition in Japan, fifth revised and additional edition.13 A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The participants in the validity study included 215 subjects (102 men and 113 women) from Cohort I and 350 subjects (174 men and 176 women) from Cohort II. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 55.6 (5.2) years among men and 53.3 (5.3) years among women in Cohort I, and 58.9 (7.6) years among men and 55.9 (7.1) years among women in Cohort II. The mean (SD) energy intakes on dietary records and the FFQ were 2386 (436) kcal and 2304 (654) kcal among men and 1854 (322) kcal and 1953 (800) kcal among women, respectively, in Cohort I, and 2269 (353) kcal and 2193 (651) kcal among men, and 1764 (257) kcal and 1835 (658) kcal among women, respectively, in Cohort II. Participants in the reliability study included 209 subjects (101 men and 108 women) from Cohort I and 289 subjects (143 men and 146 women) from Cohort II.

Amino acid intakes calculated using dietary records and the FFQs in Cohort I and their correlation are presented in Table 1. Eighteen amino acid intakes of FFQv were lower than those of dietary records in men (differences in percentages ranged from −9% to −14%), while values were similar in women (−2% to 3%). For validity, Spearman's correlation coefficients for energy-adjusted intake for all amino acids were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The median (range) was 0.35 (0.25–0.43) in men and 0.29 (0.19–0.40) in women. For reliability, the corresponding values were also significant (P < 0.0001): 0.47 (0.42–0.52) in men and 0.43 (0.38–0.50) in women.

Table 1.

Amino acid intakes calculated using dietary record for 28 days (or 14 days in Chubu) and food frequency questionnaires in Cohort I and their correlations.

| Validation |

Reliability |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary record |

FFQv |

% Differencea |

Spearman correlation |

FFQv |

FFQr |

Spearman correlation |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Crude | Adjustedb | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Crude | Adjustedb | ||

| Male (validation, n = 102; reliability, n = 101) | |||||||||||||

| Total protein, g | 90.5 | 15.4 | 81.4 | 32.2 | −10 | 0.45‡ | 0.30† | 81.0 | 32.1 | 81.5 | 32.0 | 0.56‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Isoleucine, mg | 3844 | 676 | 3427 | 1400 | −11 | 0.46‡ | 0.36‡ | 3411 | 1397 | 3442 | 1401 | 0.56‡ | 0.42‡ |

| Leucine, mg | 6842 | 1199 | 6153 | 2465 | −10 | 0.48‡ | 0.35‡ | 6124 | 2461 | 6183 | 2464 | 0.57‡ | 0.43‡ |

| Lysine, mg | 5854 | 1075 | 5215 | 2365 | −11 | 0.41‡ | 0.32† | 5188 | 2361 | 5180 | 2435 | 0.58‡ | 0.43‡ |

| Methionine, mg | 2097 | 369 | 1864 | 782 | −11 | 0.45‡ | 0.29† | 1857 | 782 | 1853 | 797 | 0.58‡ | 0.44‡ |

| Cystine, mg | 1349 | 233 | 1189 | 422 | −12 | 0.52‡ | 0.39‡ | 1184 | 421 | 1205 | 429 | 0.59‡ | 0.52‡ |

| SAA, mg | 3413 | 584 | 3022 | 1190 | −11 | 0.48‡ | 0.31† | 3010 | 1189 | 3027 | 1201 | 0.57‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Phenylalanine, mg | 3952 | 685 | 3548 | 1369 | −10 | 0.49‡ | 0.36‡ | 3531 | 1364 | 3584 | 1359 | 0.56‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Tyrosine, mg | 3031 | 526 | 2762 | 1093 | −9 | 0.49‡ | 0.34‡ | 2749 | 1090 | 2777 | 1091 | 0.57‡ | 0.45‡ |

| AAA, mg | 6974 | 1210 | 6306 | 2457 | −10 | 0.49‡ | 0.36‡ | 6275 | 2449 | 6360 | 2444 | 0.56‡ | 0.46‡ |

| Threonine, mg | 3528 | 622 | 3131 | 1309 | −11 | 0.47‡ | 0.35‡ | 3116 | 1306 | 3127 | 1319 | 0.59‡ | 0.46‡ |

| Tryptophan, mg | 1045 | 180 | 950 | 372 | −9 | 0.49‡ | 0.40‡ | 946 | 371 | 955 | 369 | 0.57‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Valine, mg | 4549 | 803 | 4107 | 1629 | −10 | 0.50‡ | 0.35‡ | 4089 | 1627 | 4121 | 1621 | 0.58‡ | 0.42‡ |

| Histidine, mg | 2997 | 547 | 2689 | 1183 | −10 | 0.35‡ | 0.35‡ | 2671 | 1175 | 2653 | 1171 | 0.59‡ | 0.42‡ |

| Arginine, mg | 5515 | 955 | 4846 | 1919 | −12 | 0.48‡ | 0.33‡ | 4823 | 1914 | 4845 | 1922 | 0.62‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Alanine, mg | 4610 | 804 | 4025 | 1665 | −13 | 0.47‡ | 0.33‡ | 4008 | 1663 | 3995 | 1687 | 0.61‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Aspartic acid, mg | 8413 | 1507 | 7446 | 3072 | −11 | 0.50‡ | 0.37‡ | 7408 | 3063 | 7433 | 3056 | 0.62‡ | 0.50‡ |

| Glutamic acid, mg | 15,668 | 2593 | 13,593 | 5198 | −13 | 0.42‡ | 0.38‡ | 13,522 | 5174 | 13,874 | 5430 | 0.54‡ | 0.50‡ |

| Glycine, mg | 4074 | 691 | 3512 | 1459 | −14 | 0.41‡ | 0.25* | 3495 | 1455 | 3516 | 1475 | 0.56‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Proline, mg | 4605 | 815 | 4213 | 1638 | −9 | 0.45‡ | 0.43‡ | 4193 | 1633 | 4323 | 1714 | 0.51‡ | 0.50‡ |

| Serine, mg | 4034 | 701 | 3584 | 1379 | −11 | 0.50‡ | 0.36‡ | 3568 | 1376 | 3616 | 1375 | 0.56‡ | 0.49‡ |

| Total amino acid, mg | 85,709 | 14,599 | 75,941 | 30,428 | −11 | 0.45‡ | 0.34‡ | 75,572 | 30,348 | 76,388 | 30,402 | 0.56‡ | 0.46‡ |

| Ammonia, mg | 1788 | 313 | 1605 | 603 | −10 | 0.50‡ | 0.42‡ | 1596 | 600 | 1638 | 619 | 0.53‡ | 0.52‡ |

| Medianc | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.47 | |||||||||

| Female (validation, n = 113; reliability, n = 108) | |||||||||||||

| Total protein, g | 75.0 | 12.8 | 75.8 | 39.5 | 1 | 0.37‡ | 0.26† | 75.3 | 40.0 | 75.8 | 26.9 | 0.67‡ | 0.43‡ |

| Isoleucine, mg | 3229 | 561 | 3240 | 1718 | 0 | 0.37‡ | 0.29† | 3218 | 1734 | 3248 | 1199 | 0.65‡ | 0.40‡ |

| Leucine, mg | 5718 | 985 | 5790 | 3014 | 1 | 0.39‡ | 0.30† | 5751 | 3042 | 5805 | 2106 | 0.65‡ | 0.39‡ |

| Lysine, mg | 4901 | 896 | 4932 | 2901 | 1 | 0.33‡ | 0.28† | 4900 | 2932 | 4908 | 2000 | 0.62‡ | 0.43‡ |

| Methionine, mg | 1727 | 300 | 1736 | 944 | 1 | 0.38‡ | 0.27† | 1727 | 956 | 1727 | 663 | 0.64‡ | 0.40‡ |

| Cystine, mg | 1117 | 189 | 1111 | 520 | 0 | 0.40‡ | 0.28† | 1107 | 526 | 1122 | 374 | 0.73‡ | 0.50‡ |

| SAA, mg | 2818 | 479 | 2821 | 1457 | 0 | 0.39‡ | 0.23* | 2807 | 1475 | 2823 | 1022 | 0.66‡ | 0.43‡ |

| Phenylalanine, mg | 3304 | 567 | 3346 | 1710 | 1 | 0.39‡ | 0.29† | 3326 | 1728 | 3362 | 1173 | 0.68‡ | 0.40‡ |

| Tyrosine, mg | 2518 | 434 | 2597 | 1341 | 3 | 0.38‡ | 0.30† | 2582 | 1355 | 2609 | 941 | 0.66‡ | 0.41‡ |

| AAA, mg | 5819 | 1001 | 5947 | 3047 | 2 | 0.38‡ | 0.31‡ | 5910 | 3078 | 5972 | 2108 | 0.68‡ | 0.40‡ |

| Threonine, mg | 2939 | 516 | 2945 | 1612 | 0 | 0.38‡ | 0.27† | 2927 | 1630 | 2943 | 1112 | 0.65‡ | 0.44‡ |

| Tryptophan, mg | 870 | 149 | 897 | 457 | 3 | 0.38‡ | 0.32‡ | 891 | 461 | 901 | 321 | 0.67‡ | 0.44‡ |

| Valine, mg | 3806 | 658 | 3873 | 1996 | 2 | 0.39‡ | 0.32‡ | 3849 | 2016 | 3880 | 1387 | 0.66‡ | 0.40‡ |

| Histidine, mg | 2449 | 447 | 2482 | 1443 | 1 | 0.26† | 0.19* | 2467 | 1461 | 2481 | 971 | 0.60‡ | 0.38‡ |

| Arginine, mg | 4468 | 802 | 4473 | 2407 | 0 | 0.39‡ | 0.24† | 4457 | 2445 | 4491 | 1626 | 0.69‡ | 0.50‡ |

| Alanine, mg | 3775 | 672 | 3740 | 2065 | −1 | 0.39‡ | 0.25† | 3723 | 2095 | 3725 | 1394 | 0.67‡ | 0.49‡ |

| Aspartic acid, mg | 7003 | 1271 | 7049 | 3928 | 1 | 0.40‡ | 0.32‡ | 7012 | 3975 | 7033 | 2563 | 0.69‡ | 0.48‡ |

| Glutamic acid, mg | 13,299 | 2182 | 13,017 | 6578 | −2 | 0.34‡ | 0.32‡ | 12,918 | 6618 | 13,089 | 4507 | 0.67‡ | 0.42‡ |

| Glycine, mg | 3322 | 582 | 3246 | 1812 | −2 | 0.37‡ | 0.19* | 3233 | 1840 | 3236 | 1246 | 0.68‡ | 0.48‡ |

| Proline, mg | 4003 | 680 | 4080 | 1959 | 2 | 0.36‡ | 0.39‡ | 4042 | 1960 | 4123 | 1477 | 0.63‡ | 0.43‡ |

| Serine, mg | 3381 | 582 | 3384 | 1701 | 0 | 0.40‡ | 0.31‡ | 3367 | 1720 | 3411 | 1211 | 0.68‡ | 0.44‡ |

| Total amino acid, mg | 71,613 | 12,187 | 71,656 | 37,763 | 0 | 0.37‡ | 0.28† | 71,210 | 38,158 | 71,814 | 25,899 | 0.66‡ | 0.41‡ |

| Ammonia, mg | 1527 | 265 | 1551 | 771 | 2 | 0.38‡ | 0.40‡ | 1538 | 774 | 1555 | 514 | 0.69‡ | 0.50‡ |

| Medianc | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.43 | |||||||||

AAA, Aromatic amino acids; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; SAA, sulfur-containing amino acids.

Values reported in mg, unless otherwise noted.

Significance level: *P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, ‡P < 0.001.

(FFQ mean − dietary record mean)/dietary record mean.

Amino acid were adjusted for total energy intake using the residual method.

Median of correlation coefficients for crude amino acids and for energy-adjusted intakes of amino acids.

We also assessed the validity and reliability in Cohort II (Table 2). Differences in percentages among 18 amino acids ranged from −10% to −17% in men and 0 to −5% in women. For validity, Spearman's correlation coefficients for energy-adjusted intake for all amino acids were statistically significant (P < 0.01). The median (range) was 0.37 (0.21–0.52) in men and 0.38 (0.24–0.59) in women. The corresponding values for reliability were also significant (P < 0.0001): 0.59 (0.52–0.70) in men and 0.54 (0.45–0.61) in women.

Table 2.

Amino acid intakes calculated using dietary record for 28 days and food frequency questionnaires in Cohort II and their correlations.

| Validation |

Reliability |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary record |

FFQv |

% Differencea |

Spearman correlation |

FFQv |

FFQr |

Spearman correlation |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Crude | Adjustedb | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Crude | Adjustedb | ||

| Male (validation, n = 174; reliability, n = 143) | |||||||||||||

| Total protein, g | 88 | 15 | 76 | 29 | −14 | 0.28‡ | 0.32‡ | 74 | 27 | 80 | 31 | 0.60‡ | 0.60‡ |

| Isoleucine, mg | 3706 | 660 | 3198 | 1267 | −14 | 0.27‡ | 0.37‡ | 3136 | 1193 | 3378 | 1341 | 0.60‡ | 0.60‡ |

| Leucine, mg | 6599 | 1144 | 5756 | 2231 | −13 | 0.28‡ | 0.37‡ | 5639 | 2093 | 6075 | 2355 | 0.59‡ | 0.60‡ |

| Lysine, mg | 5679 | 1159 | 4867 | 2134 | −14 | 0.28‡ | 0.31‡ | 4767 | 2046 | 5140 | 2226 | 0.60‡ | 0.57‡ |

| Methionine, mg | 2020 | 383 | 1743 | 706 | −14 | 0.29‡ | 0.27‡ | 1703 | 674 | 1829 | 725 | 0.60‡ | 0.56‡ |

| Cystine, mg | 1296 | 202 | 1105 | 375 | −15 | 0.27‡ | 0.42‡ | 1087 | 357 | 1169 | 422 | 0.60‡ | 0.59‡ |

| SAA, mg | 3288 | 573 | 2820 | 1066 | −14 | 0.27‡ | 0.31‡ | 2763 | 1019 | 2969 | 1135 | 0.60‡ | 0.56‡ |

| Phenylalanine, mg | 3816 | 630 | 3314 | 1223 | −13 | 0.26‡ | 0.41‡ | 3253 | 1148 | 3506 | 1330 | 0.60‡ | 0.62‡ |

| Tyrosine, mg | 2922 | 506 | 2575 | 977 | −12 | 0.28‡ | 0.37‡ | 2525 | 922 | 2722 | 1050 | 0.61‡ | 0.59‡ |

| AAA, mg | 6737 | 1134 | 5891 | 2205 | −13 | 0.27‡ | 0.40‡ | 5779 | 2071 | 6226 | 2385 | 0.61‡ | 0.60‡ |

| Threonine, mg | 3414 | 626 | 2912 | 1167 | −15 | 0.28‡ | 0.33‡ | 2857 | 1119 | 3081 | 1245 | 0.60‡ | 0.57‡ |

| Tryptophan, mg | 1015 | 173 | 889 | 336 | −12 | 0.27‡ | 0.39‡ | 872 | 317 | 940 | 366 | 0.61‡ | 0.62‡ |

| Valine, mg | 4379 | 759 | 3833 | 1476 | −12 | 0.29‡ | 0.38‡ | 3754 | 1386 | 4041 | 1559 | 0.60‡ | 0.60‡ |

| Histidine, mg | 2919 | 648 | 2504 | 1079 | −14 | 0.29‡ | 0.30‡ | 2423 | 998 | 2646 | 1130 | 0.60‡ | 0.57‡ |

| Arginine, mg | 5283 | 942 | 4446 | 1664 | −16 | 0.28‡ | 0.31‡ | 4372 | 1610 | 4716 | 1798 | 0.61‡ | 0.52‡ |

| Alanine, mg | 4421 | 829 | 3707 | 1472 | −16 | 0.28‡ | 0.25‡ | 3639 | 1428 | 3925 | 1577 | 0.61‡ | 0.54‡ |

| Aspartic acid, mg | 8101 | 1488 | 6846 | 2684 | −15 | 0.30‡ | 0.36‡ | 6727 | 2571 | 7240 | 2913 | 0.62‡ | 0.57‡ |

| Glutamic acid, mg | 15,442 | 2450 | 12,954 | 4766 | −16 | 0.21† | 0.42‡ | 12,745 | 4484 | 13,745 | 5210 | 0.58‡ | 0.63‡ |

| Glycine, mg | 3900 | 717 | 3229 | 1281 | −17 | 0.26‡ | 0.21† | 3180 | 1249 | 3443 | 1380 | 0.59‡ | 0.52‡ |

| Proline, mg | 4536 | 738 | 4073 | 1597 | −10 | 0.28‡ | 0.52‡ | 3996 | 1453 | 4304 | 1652 | 0.58‡ | 0.70‡ |

| Serine, mg | 3898 | 645 | 3358 | 1241 | −14 | 0.28‡ | 0.43‡ | 3298 | 1180 | 3542 | 1329 | 0.61‡ | 0.61‡ |

| Total amino acid, mg | 83,070 | 14,248 | 71,020 | 27,238 | −15 | 0.25‡ | 0.35‡ | 69,699 | 25,851 | 75,143 | 29,224 | 0.59‡ | 0.58‡ |

| Ammonia, mg | 1750 | 276 | 1515 | 555 | −13 | 0.25‡ | 0.46‡ | 1492 | 517 | 1606 | 613 | 0.59‡ | 0.65‡ |

| Medianc | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.6 | 0.59 | |||||||||

| Female (validation, n = 176; reliability, n = 146) | |||||||||||||

| Total protein, g | 72 | 11 | 71 | 31 | −2 | 0.34‡ | 0.36‡ | 70 | 28 | 75 | 28 | 0.66‡ | 0.53‡ |

| Isoleucine, mg | 3072 | 496 | 3014 | 1376 | −2 | 0.35‡ | 0.39‡ | 2987 | 1237 | 3197 | 1224 | 0.66‡ | 0.53‡ |

| Leucine, mg | 5460 | 873 | 5400 | 2417 | −1 | 0.35‡ | 0.39‡ | 5348 | 2168 | 5717 | 2136 | 0.66‡ | 0.54‡ |

| Lysine, mg | 4653 | 811 | 4587 | 2295 | −1 | 0.34‡ | 0.34‡ | 4527 | 2037 | 4872 | 2038 | 0.65‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Methionine, mg | 1631 | 270 | 1609 | 751 | −1 | 0.35‡ | 0.31‡ | 1581 | 665 | 1702 | 644 | 0.66‡ | 0.51‡ |

| Cystine, mg | 1065 | 157 | 1023 | 408 | −4 | 0.33‡ | 0.36‡ | 1013 | 364 | 1082 | 375 | 0.65‡ | 0.54‡ |

| SAA, mg | 2673 | 417 | 2606 | 1146 | −2 | 0.34‡ | 0.32‡ | 2568 | 1015 | 2758 | 1005 | 0.66‡ | 0.56‡ |

| Phenylalanine, mg | 3168 | 490 | 3111 | 1339 | −2 | 0.36‡ | 0.41‡ | 3085 | 1196 | 3290 | 1208 | 0.66‡ | 0.56‡ |

| Tyrosine, mg | 2406 | 381 | 2412 | 1070 | 0 | 0.35‡ | 0.39‡ | 2390 | 954 | 2553 | 951 | 0.67‡ | 0.56‡ |

| AAA, mg | 5580 | 872 | 5530 | 2405 | −1 | 0.35‡ | 0.40‡ | 5484 | 2157 | 5850 | 2167 | 0.66‡ | 0.57‡ |

| Threonine, mg | 2800 | 449 | 2727 | 1268 | −3 | 0.34‡ | 0.34‡ | 2693 | 1123 | 2894 | 1123 | 0.66‡ | 0.51‡ |

| Tryptophan, mg | 840 | 132 | 837 | 370 | 0 | 0.36‡ | 0.42‡ | 830 | 329 | 885 | 334 | 0.66‡ | 0.55‡ |

| Valine, mg | 3628 | 574 | 3599 | 1596 | −1 | 0.36‡ | 0.40‡ | 3565 | 1441 | 3809 | 1418 | 0.66‡ | 0.55‡ |

| Histidine, mg | 2320 | 404 | 2319 | 1250 | 0 | 0.33‡ | 0.35‡ | 2260 | 992 | 2441 | 1003 | 0.65‡ | 0.51‡ |

| Arginine, mg | 4245 | 660 | 4085 | 1779 | −4 | 0.34‡ | 0.33‡ | 4030 | 1554 | 4318 | 1632 | 0.68‡ | 0.45‡ |

| Alanine, mg | 3557 | 560 | 3419 | 1566 | −4 | 0.33‡ | 0.29‡ | 3362 | 1370 | 3628 | 1404 | 0.67‡ | 0.47‡ |

| Aspartic acid, mg | 6676 | 1055 | 6449 | 2901 | −3 | 0.35‡ | 0.36‡ | 6389 | 2577 | 6828 | 2734 | 0.67‡ | 0.48‡ |

| Glutamic acid, mg | 12,974 | 2009 | 12,291 | 5287 | −5 | 0.32‡ | 0.46‡ | 12,221 | 4750 | 13,025 | 4685 | 0.66‡ | 0.59‡ |

| Glycine, mg | 3120 | 493 | 2961 | 1360 | −5 | 0.29‡ | 0.24† | 2914 | 1176 | 3145 | 1216 | 0.68‡ | 0.50‡ |

| Proline, mg | 3920 | 682 | 3928 | 1776 | 0 | 0.35‡ | 0.59‡ | 3920 | 1642 | 4160 | 1540 | 0.67‡ | 0.61‡ |

| Serine, mg | 3243 | 505 | 3146 | 1359 | −3 | 0.37‡ | 0.41‡ | 3117 | 1223 | 3328 | 1204 | 0.66‡ | 0.56‡ |

| Total amino acid, mg | 68,604 | 10,665 | 66,674 | 29,789 | −3 | 0.33‡ | 0.38‡ | 65,996 | 26,395 | 70,630 | 26,433 | 0.66‡ | 0.54‡ |

| Ammonia, mg | 1481 | 226 | 1451 | 618 | −2 | 0.36‡ | 0.51‡ | 1447 | 556 | 1538 | 567 | 0.64‡ | 0.57‡ |

| Medianc | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 0.54 | |||||||||

AAA, Aromatic amino acids; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; SAA, sulfur-containing amino acids.

Values reported in mg, unless otherwise noted.

Significance level: *P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, ‡P < 0.001.

(FFQ mean − dietary record mean)/dietary record mean.

Amino acid were adjusted for total energy intake using the residual method.

Median of correlation coefficients for crude amino acids and for energy-adjusted intakes of amino acids.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the validity and reliability of an FFQ for assessment of amino acid intakes. The validity was evaluated by comparing the results obtained from the FFQ with those from dietary records, and the reliability was estimated by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficients between results of two FFQs among the same participants. Results using the revised Table of Food Composition showed improved validity in comparison with results using the pre-revised Table of Food Composition and good reliability of the FFQ for ranking individuals.

Dietary intakes of amino acids from the FFQ were underestimated compared with those from dietary records. The underestimation ranged from −9 to −17% in men but only 0 to −5% in women. Because women spend more time at home than men,14 women may respond to the questionnaire more accurately than men. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has assessed the validity of the FFQ for amino acids. While an association has been reported between dietary cysteine intake, which was calculated from the FFQ, and the risk of stroke in a Swedish cohort, this study only evaluated protein intake and not dietary cysteine intake at the amino acid level.1, 15

Using a comprehensive database of amino acids that was constructed based on the Amino Acid Composition of Foods Revised edition, which was published in 1986 as a follow-up to the fourth edition of the Standardized Table of Food Composition in Japan and included 295 food items,16 a previous study examined the validity of the same FFQ for the assessment of amino acids.6 Compared with the previous study, the current study, using a new database, found better validity overall. Although the validity of the FFQ among women in a previous study was low, the median of energy-adjusted correlation coefficients was improved in both Cohort I (from 0.24 to 0.29) and II (from 0.29 to 0.38).6 In the present study, component values were still calculated using the substitution method for many food items, although the number of original food items increased from 295 to 337. As more food items are added to the Standardized Table of Food Composition in Japan, results may get even better, since the addition of new foods in the 2010 version showed improvements over the previous version.

The energy-adjusted correlations for the reliability of the FFQ to estimate amino acid intakes were 0.57 in men and 0.67 in women of Cohort I, and 0.59 in men and 0.54 in women of Cohort II. These values indicated good reliability, although the present results cannot be compared with those of the previous study because the previous study, which was based on the previous edition of the amino acid composition table in Japan, did not examine reliability.6

In conclusion, compared with dietary records, the FFQ used in our prospective cohort study is a suitable tool for estimating amino acid intakes in Japanese men and women of this study population.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (23-A-31[toku] and 26-A-2) (since 2011) and a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (from 1989 to 2010). The authors thank all staff members in each study area and in the central office for their painstaking efforts to conduct the baseline survey and follow-up.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japan Epidemiological Association.

Appendix.

The investigators in the validation study of the self-administered FFQ in the JPHC Study (the JPHC FFQ Validation Study Group) and their affiliations at the time of the study were: S. Tsugane, S. Sasaki, and M. Kobayashi, Epidemiology and Biostatistics Division, National Cancer Center Research Institute East, Kashiwa; T. Sobue, S. Yamamoto, and J. Ishihara, Cancer Information and Epidemiology Division, National Cancer Center Research Institute, Tokyo; M. Akabane, Y. Iitoi, Y. Iwase, and T. Takahashi, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo; K. Hasegawa and T. Kawabata, Kagawa Nutrition University, Sakado; Y. Tsubono, Tohoku University, Sendai; H. Iso, Tsukuba University, Tsukuba; S. Karita, Teikyo University, Tokyo; the late M. Yamaguchi and Y. Matsumura, National Institute of Health and Nutrition, Tokyo.

References

- 1.Larsson S.C., Håkansson N., Wolk A. Dietary cysteine and other amino acids and stroke incidence in women. Stroke. 2015;46:922–926. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virtanen J.K., Voutilainen S., Rissanen T.H. High dietary methionine intake increases the risk of acute coronary events in middle-aged men. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;116:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preis S.R., Stampfer M.J., Spiegelman D., Willett W.C., Rimm E.B. Dietary protein and risk of ischemic heart disease in middle-aged men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1265–1272. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poloni S., Blom H.J., Schwartz I.V. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1: is it the link between sulfur amino acids and lipid metabolism? Biology. 2015;4:383–396. doi: 10.3390/biology4020383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Council for Science and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Government of Japan . Official Gazette Cooperation of Japan; Tokyo: 2010. Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan, Amino Acid Composition of Foods 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishihara J., Todoriki H., Inoue M., Tsugane S., for the JPHC FFQ Validation Study Group Validity of a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire in the estimation of amino acid intake. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:1393–1399. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508079609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsugane S., Sasaki S., Kobayashi M., Tsubono Y., Sobue T for JPHC study group Dietary habits among the JPHC study participants at baseline survey. J Epidemiol. 2001;11(suppl):S30–S43. doi: 10.2188/jea.11.6sup_30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsugane S., Sasaki S., Kobayashi M., Tsubono Y., Akabane M. Validity and reproducibility of the self-administered food frequency questionnaire in the JPHC study Cohort 1: study design, conduct and participant profiles. J Epidemiol. 2003;13(suppl):S2–S12. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.1sup_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishihara J., Sobue T., Yamamoto S. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire in the JPHC study Cohort II: study design, participant profile and results in comparison with Cohort I. J Epidemiol. 2003;13(suppl):S134–S147. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.1sup_134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willet W. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, Inc.; Oxford, UK: 2012. Nutrition Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Council for Science and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Government of Japan . Official Gazette Cooperation of Japan; Tokyo: 2010. Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato Y., Otsuka R., Imai T., Ando F., Shimokata H. Estimation of dietary amino acid intake in community-dwelling middle-aged and elderly individuals using a newly constructed amino acid food composition table. Jpn J Nutr Diet. 2013;71:299–310. [in Japanese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council for Science and Technology/Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology/the Government of Japan . Printing Bureau, Ministry of Finance; Tokyo: 2005. Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan, the Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Bureau . National Statics Center Japan; Tokyo: 2013. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. 2011 Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messerer M., Johansson S.E., Wolk A. The validity of questionnaire-based micronutrient intake estimates is increased by including dietary supplement use in Swedish men. J Nutr. 2004;134:1800–1805. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.7.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resource Council, Science and Technology Agency & the Government of Japan . Printing Bureau, Ministry of Finance; Tokyo: 1986. Amino Acid Composition of Foods in Japan, Revised Ed. [Google Scholar]