J K Rowling's Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets1 includes a scene in which the hero and his friends are in a greenhouse, taking instruction from Professor Sprout on the re-potting of mandrakes. To protect their hearing, the class is equipped with earmuffs.

In an age ever more preoccupied with medicinal herbs, mandrake is the herb that time has forgotten, the word more readily associated today with a column in the Sunday Telegraph or the American strip cartoon Mandrake the Magician. Mandrake the Magician (1934) was the first super-powered costumed crime fighter, the forerunner of Superman, Batman and, most recently Spiderman, but even this icon of the 20th century had his origin in antiquity, for the unlikely source of his creator Lee Falk's inspiration was a poem by the 17th century English poet John Donne2. Donne's subject was fertility:

‘Goe, and catche a falling starre,

Get with child a mandrake roote’.

And the origin of the mandrake's association with fertility is truly ancient, surfacing first in chapter 30 of the Book of Genesis, where the childless Rachael asks her sister Leah for the loan of the mandrakes which her son had brought in from the fields. Much later, this fertility myth received support from the medieval doctrine of signatures, which suggested that God had provided all plants with a sign indicating their value. Mandrake has a long and frequently bifid taproot whose shape sometimes resembles the body of a man (Figure 1). Believing this to indicate reproductive power, our ancestors took to sleeping with them under their pillows at night.

Figure 1.

Mandrake (Mandragora officinarum). Sibthorpe: Flora Graeca (1808)

Others, however, began to wonder whether the possession of roots might not bring them success in other areas as well—wealth, popularity, or the power to control their own and other people's destinies, and took to wearing them as good luck charms. Not surprisingly, the Church frowned upon this practice and when, during her trial in 1431, Joan of Arc was accused of having a mandrake about her person, the suggestion helped send her to the stake3.

Mandrake was, of course, far from being the only plant with an anthropomorphic root. The herb had another property, however, for the root contains hyoscine a powerful alkaloid with the ability to cause hallucinations, delirium and, in larger doses, coma. Mandrake's use as a surgical anaesthetic was first described by the Greek physician Dioscorides around AD 60, and its use as a tincture known as mandragora, or in combination with other herbs such as opium, hemlock and henbane is described in documents from pre-Roman times onwards4. It was the presence of this alkaloid, as well as the shape of the root, that led to the mandrake's association with magic, witchcraft and the supernatural.

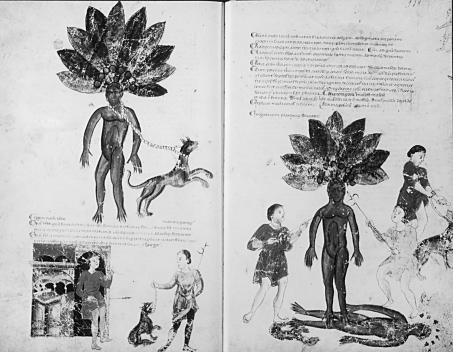

Mandrake roots became highly sought after in their native Mediterranean habitat, and attempts to protect them from theft are thought to have been the source of the second mandrake myth, which stated that a demon inhabited the root and would kill anyone who attempted to uproot it. Over the centuries, elaborate rituals developed to avoid what became known as the mandrake's curse, the most famous of these requiring the assistance of a dog (Figure 2). Later elaboration of this legend attributed the herb's lethal power to a shriek or a groan emitted by the mandrake as it was uprooted, and suggested that death could be avoided either by a loud blast on a horn at the critical moment or by sealing one's ears with wax. In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, the earmuff is more in keeping with current health and safety regulations.

Figure 2.

The mandrake's curse. After being shown a tasty morsel (far right), a hungry dog is tied to the root of the mandrake. From a safe distance, the hunter throws the food in front of the dog, which lunges forward, uprooting the herb. The dog dies at sunrise (bottom right) and is buried with secret rites. Cod. Vind. (Medicina Antiqua)

THE ENGLISH MANDRAKE

Although mandrake found its way into Britain around the 11th century, the herb does not grow naturally here, and anyone wishing to avail himself of its powers, real, or imaginary, was therefore obliged to seek an alternative. Those in search of its medicinal effects turned to henbane, Hyoscyamus niger, a closely related herb with a similar pharmacological profile to mandrake but a more northerly distribution. Henbane was a potent ingredient in the various midnight brews and flying ointments beloved of witches and is thought to have been the ‘cursed hebenon’ poured into the ear of Hamlet's father.

Those seeking to profit from the demand for mandrake charms would have found henbane a disappointment, for it possessed only a small fibrous root. For this purpose they turned instead to the white bryony, Bryonia dioica, a hedgerow plant of south-east England with a large multilobed taproot5 (Figure 3). Competitions were held to find the most realistic (and suggestive) examples6 and, in his New Herball of 1568, Dr William Turner, the clerical-medical Dean of Wells Cathedral and father of English botany, described how specimens were further embellished with a knife and by the superficial insertion of millet seeds to create, after germination, a ‘beard’:

Figure 3.

The white bryony (Bryonia dioica). Alyon: La Botanique (1785)

‘The rootes which are counterfited and made like little pupettes or mammettes which come to be sold in England in boxes with heir and such forme as a man hath are nothyng elles but foolishe trifles and not naturall. For they are so trymmed of crafty theves to mocke the poore people with all and to rob them both of theyr wit and theyr money’7.

Bryony roots also came to be used in witches' brews8 and, although lacking any narcotic power of their own, even found their way into primitive anaesthetic mixtures, such as one mentioned in the Canterbury Tales and known as dwale9.

POETIC LICENCE

Genuine mandrake roots, presumably imported, and preparations made from them, were also available at this time and Turner gives fascinating instructions for their use as anaesthetics while at the same time describing the unpredictability that was responsible for the rapid decline in their use everywhere. The popularity of the myths, however, remained undimmed.

The works of William Shakespeare contain many references to the mandrake and its myths (Box 1) and are remarkable both for the depth of knowledge they reveal and for their accuracy. Other writers, however, used considerable artistic licence and no more ingenious example of this exists than the comedy The Mandrake Root by the Florentine writer Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527), which unites the mandrake's fertility myth with its curse10. The story concerns a rake, Callimoco, who concocts a plan to help satisfy his lust for the young wife of a local lawyer. Aware of the couple's desire to start a family, Callimoco offers the wife a potion made from the mandrake root, but persuades her husband that the first man to sleep with her afterwards will die. The gullible lawyer agrees to the use of a local tramp as a ‘stand-in’ for the first night, and Callimoco dons his tramp's disguise to await the summons.

Box 1 Shakespeare on mandrake

Sedative

Give me to drink mandragora,

That I might sleep out this great gap of time

My Antony is away.

Anthony and Cleopatra Act I, Sc. 5

Not poppy, nor mandragora,

Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,

Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep

Which thou owdst yesterday.

Othello Act III, Sc. 3

Were such things here as we do speak about?

Or have we eaten of the insane root

That takes the reason prisoner?

Macbeth Act I, Sc. 3

Charm

Thou whoreson mandrake, thou art fitter to be worn in my cap than to wait at my heels.

Henry IV Part Two Act I, Sc. 2

... he was for all the world like a forked radish, with a head fantastically carved upon it with a knife. He was so forlorn, that his dimensions to any thick sight were invisible;...... yet lecherous as a monkey, and the whores called him mandrake.

Henry IV Part Two Act III, Sc. 2

Curse

What with loathsome smells,

And shrieks like mandrakes torn out of the earth,

That living mortals, hearing them, run mad...

Romeo and Juliet Act IV, Sc. 3

Would curses kill, as doth the mandrake's groan.

Henry VI Part Two Act III, Sc. 2

THE LITTLE GALLOWS MAN

Around this time, an apparently new myth began to circulate, to the effect that a mandrake would spring up from ground contaminated by human blood or semen, such as at the foot of a gallows. Once again, Dr Turner, who had spent some years in Europe, was quick to condemn those responsible:

‘But it groweth not under gallosses as a certain dotyng doctor of Colon in hys physick lecture dyd tych hys auditores; nether doth it ryse of the sede of man that falleth from hym that is hanged; Neither is it called Mandragora because it came of man's sede, as ye forsayd doctor dremed’.

Playwrights, nonetheless, wasted little time in taking this new myth to their hearts and, in his corspe-strewn tragedy The White Devil John Webster (1578—c. 1630) (erroneously) unites the mistletoe and mandrake, good and evil, with the tree which, with its horizontal lower branches, had long made a convenient impromptu gallows:

‘But as we seldom find the mistletoe

Sacred to physic on the builder oak,

Without a mandrake by it, so in our quest of gain’.

In the film Shakespeare in Love, Webster is portrayed as a mousy adolescent who condescendingly informs the Bard ‘plenty of blood, that's the only writing’, and this new myth was right up his street. In Act III, scene iii of the play, Lodoveco gives orders for his sister's murder:

‘Wilt sell me forty ounces of her blood

To water a mandrake’.

Whilst, finally, in Act V, scene vi, Webster raises the mandrake's curse to even greater heights of the macabre:

‘Millions are now in graves, which at last day

Like mandrakes shall rise shrieking’.

In more recent centuries, mandrake myths have continued to provide writers with inspiration, and not only those writing for the theatre, as, for example, in Act I, scene ii of Verdi's opera Un Ballo in Maschera (1857) when Amelia, the governor's wife, seeks a cure for a guilty passion from the gypsy woman Ulrica. Ulrica tells her:

‘Oblivion I can give you. Mystic drops of a magic herb I know that renews the heart. But whoever wants it must gather it with his own hand at the dead of night—the graveyard is the place. To the west of the city, there, where on the gloomy field the pallid moon shines down on abhorrent land the herb has its roots by those ill-famed stones where all sins are atoned for with the last living breath!’

Later, Amelia approaches the fateful spot: ‘Here is the horrible field where death is the atonement for crime. There are the pillars the plants at their feet.’

ENVOI

Folklore based upon the mandrake myths survived well into the 20th century:

‘In December 1908, a man employed in digging a neglected garden half a mile from Stratford upon Avon, cut a large root of white bryony through with his spade. He called it mandrake, and ceased to work at once, saying it was ‘awful bad luck’. Before the week was out, he fell down some steps and broke his neck’6.

References

- 1.Rowling JK. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. London: Bloomsbury, 1998: 72

- 2.Father of the Phantom. Cartoonist Profiles 1975;27: 20-4 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson CJS. The Mystic Mandrake. London: Rider, 1934: 146

- 4.Carter AJ. Narcosis and nightshade. BMJ 1996;313: 1630-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reader's Digest. Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain. London: Reader's Digest Association, 1981: 157

- 6.Vicary R. Oxford Dictionary of Plant-lore. Oxford: University Press, 1995: 393-4

- 7.Chapman GTL, McCombie F, Wesencraft A, eds. William Turner: A New Herball, Vol. 2. Cambridge: University Press, 1996: 437 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huson P. Mastering Witchcraft. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1970: 146

- 9.Carter AJ. Dwale: an anaesthetic from old England. BMJ 1999;319: 1623-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bondanella P, Musa M, eds. The Portable Machiavelli. London: Penguin, 1979: 430