ABSTRACT

Basal cells in a simple secretory epithelium adhere to the extracellular matrix (ECM), providing contextual cues for ordered repopulation of the luminal cell layer. Early high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HG-PIN) tissue has enlarged nuclei and nucleoli, luminal layer expansion and genomic instability. Additional HG-PIN markers include loss of α6β4 integrin or its ligand laminin-332, and budding of tumor clusters into laminin-511-rich stroma. We modeled the invasive budding phenotype by reducing expression of α6β4 integrin in spheroids formed from two normal human stable isogenic prostate epithelial cell lines (RWPE-1 and PrEC 11220). These normal cells continuously spun in culture, forming multicellular spheroids containing an outer laminin-332 layer, basal cells (expressing α6β4 integrin, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin and p63, also known as TP63) and luminal cells that secrete PSA (also known as KLK3). Basal cells were optimally positioned relative to the laminin-332 layer as determined by spindle orientation. β4-integrin-defective spheroids contained a discontinuous laminin-332 layer corresponding to regions of abnormal budding. This 3D model can be readily used to study mechanisms that disrupt laminin-332 continuity, for example, defects in the essential adhesion receptor (β4 integrin), laminin-332 or abnormal luminal expansion during HG-PIN progression.

KEY WORDS: Prostate, Neoplasia, Integrin, Laminin, Spheroids

Summary: A dynamic 3D model of HG-PIN was created using immortalized human prostate epithelial cells with a basal cell defect. The model can be used to test molecular events that disrupt cancer progression.

INTRODUCTION

The normal prostate gland is a simple secretory epithelium containing a basal cell population [which can be detected by analyzing for the presence of high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMWCK)] harboring stem cells (Bonkhoff, 1996; Bonkhoff and Remberger, 1996; Bostwick, 1996a,b) and a luminal cell population [detected by racemase (AMACR) staining] that secretes PSA (also known as KLK3) (Thomson and Marker, 2006). During normal glandular development, extracellular matrix (ECM)–cell-receptor interaction provides contextual cues and a developmental ‘morphogenesis checkpoint’ for ordered repopulation (Brown, 2011). Cell divisions parallel to the basal cell surface maintain proximity to the ECM and control mitotic spindle orientation during epithelial morphogenesis and repair (Xia et al., 2015).

During the early stages of prostate cancer progression, a defective glandular structure forms, called high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HG-PIN), which is defined by focal loss or attenuation of the basal cell layer and ECM (Nagle et al., 1994), and loss of both integrin α6β4 expression and its the corresponding ECM ligand laminin-332 (i.e. laminin comprising the α3Aβ3γ2 chains) (Cress et al., 1995; Davis et al., 2001; Hao et al., 1996; Nagle et al., 1995; Pontes-Junior et al., 2009). HG-PIN often contains a mixture of basal and luminal cell markers, consistent with a loss of normal contextual cues and mitotic spindle misorientation (Bonkhoff and Remberger, 1996) as seen during regrowth of prostate following castration and androgen reintroduction (Verhagen et al., 1988). HG-PIN has genomic instability (Haffner et al., 2016; Iwata et al., 2010; Mosquera et al., 2009, 2008; Nagle et al., 1992; Petein et al., 1991) and is a precursor of invasive prostate cancer (Bonkhoff and Remberger, 1996; Bostwick, 1996a,b; Bostwick et al., 1996; Haggman et al., 1997; Montironi et al., 1996a,b; Montironi and Schulman, 1996).

Here, we report a new three-dimensional (3D) HG-PIN-type model using two different isogenic human prostate epithelial cell lines, called RWPE-1 (Bello et al., 1997; Roh et al., 2008; Webber et al., 1997) and PrEC 11220, with a stable modification to deplete β4 integrin expression. The model provides a means to test consequences of basal cell defects in human HG-PIN progression.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Human HG-PIN in tissue and the absence of α6β4 integrin expression

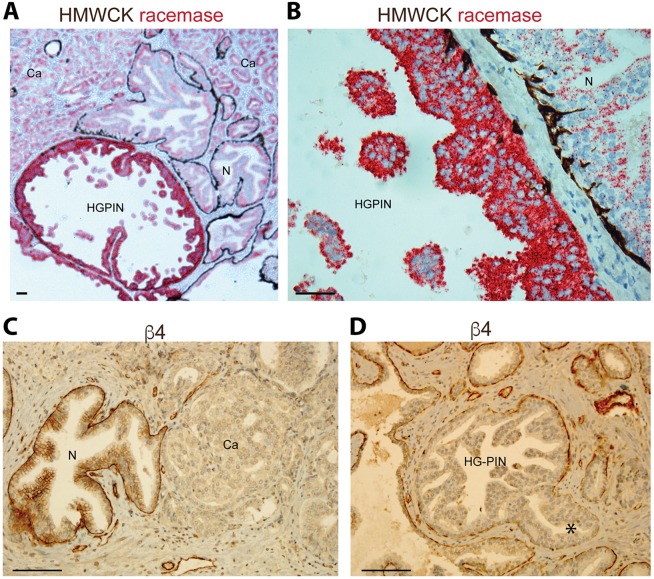

Normal human prostate glands contain an ordered basal and luminal cell distribution, as shown in Fig. 1A,B. Integrin α6β4 is found within the basal cell layer (Fig. 1C) and is required for anchoring basal cells to laminin-332 ECM through the hemidesmosome (Nagle et al., 1995; Pulkkinen and Uitto, 1998; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006). In contrast, HG-PIN (Fig. 1A,B) contains cells with enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli that proliferate within the lumen, enlarging the glands, resulting in continuity gaps (Nagle and Cress, 2011). In these gaps, laminin-332 and α6β4 integrin – essential requirements for functional hemidesmosomes – are absent; HG-PIN and cancer lesions are known to lack basal cells and laminin-332 deposition, becoming exposed to laminin-511 (i.e. laminin comprising the α5β1γ1 chains) within the muscle stroma (Davis et al., 2001; Nagle and Cress, 2011; Nagle et al., 1995). Defective β4 integrin function results in defective laminin-332 assembly (Yurchenco, 2015) and laminin-511 is a known potent morphogen essential for embryonic development (Ekblom et al., 1998). We observed extensive budding of cell clusters through β4 integrin gaps and into the stroma in HG-PIN (Fig. 1D, asterisk). Hence, loss of α6β4 integrin is associated with abnormal outgrowth of the epithelium in human HG-PIN.

Fig. 1.

Human HG-PIN in tissue and the focal absence of α6β4 integrin expression. (A,B) Human prostate tissue was stained for HMWCK (brown stain) to mark basal cells and α-methylacyl CoA racemase (P504S, red stain) to mark luminal cells (Kumaresan et al., 2010). (A) Representative image showing continuous distribution of basal cells at the base of normal prostate gland (N), discontinuous distribution of basal cells at the base of the gland, and expansion of cells into the lumen in high-grade PIN (HG-PIN) and prostate carcinoma (Ca). Note the loss of basal cell layer in cancer. (B) Higher magnification of region in A illustrating basal cell (brown stain) attenuation and continuity gaps in HG-PIN as compared to normal gland. (C,D) Human prostate tissue stained for integrin β4, showing basal cell distribution as in A and B. Note the budding of HG-PIN into muscle stroma (asterisk). Scale bars: 100 µm.

A 3D model for prostate glands contains basal and luminal cell architecture

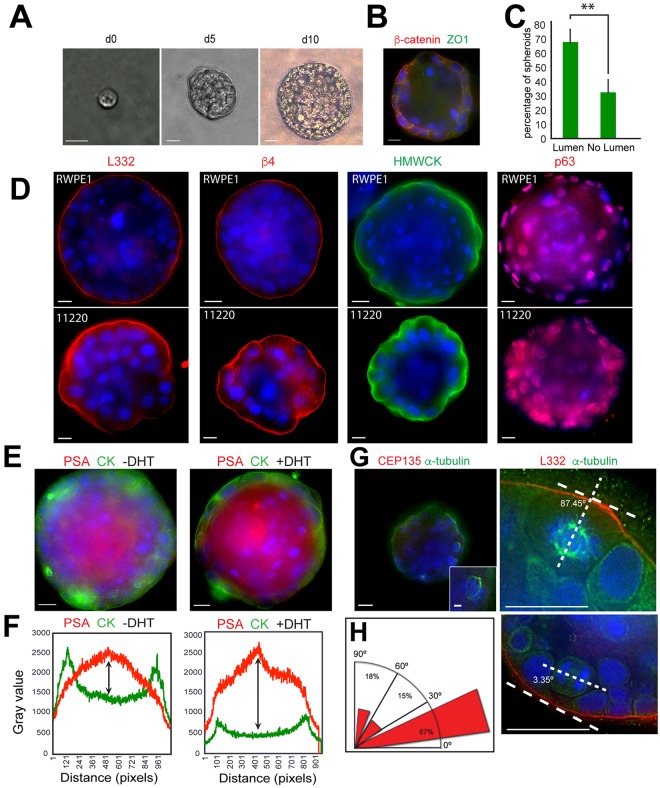

Given the importance of the glandular structure for maintaining homeostasis (Brown, 2011; Chandramouly et al., 2007; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2015) and the role of the basal cell stem cell compartment (Bonkhoff and Remberger, 1996; Bostwick, 1996b; Hudson, 2004; Karthaus et al., 2014; Schmelz et al., 2005), we generated a 3D model of prostate glands using two different primarily diploid prostate epithelial cell lines, RWPE-1 and PrEC 11220. RWPE-1 is a stable non-tumorigenic human cell line derived from a histologically normal adult human prostate (Bello et al., 1997; Roh et al., 2008; Webber et al., 1997) and is used as a normal prostate cell line in genomic and differentiation studies (Wang et al., 2011; Webber et al., 1997). We note that RWPE-1 was isolated from a donor undergoing cryoprostatectomy and might carry abnormalities. The cell line was immortalized by HPV-18 and has characteristics of an intermediate cell type (Verhagen et al., 1992) expressing both basal and luminal cell cytokeratin, androgen receptor and PSA in response to androgen (Bello et al., 1997). For comparison to RWPE-1 cells, we used another normal human prostate cell line (PrEC 11220), immortalized by hTERT, to test spheroid formation (Dalrymple et al., 2005; Salmon et al., 2000). We found both cell lines formed compact multicellular spheroids as represented by RWPE-1 (Fig. 2A) and observed a dramatic cell-spinning phenotype as spheroids formed from a single cell (Movies 1 and 2). The rotational motion was similar to mammary epithelial acini that coordinate rotational movement with laminin matrix assembly (Wang et al., 2013). Most (65%) of the RWPE-1 spheroids contained a lumen after 10 days, as measured by presence of β-catenin on the cell surface and absence of DAPI staining nuclei in the interstices of the spheroid (Fig. 2B,C). Positive detection of four different molecular markers [laminin-332 production and organization, α6β4 integrin expression, HMWCK and p63 (also known as TP63)] confirmed the presence of basal cells within spheroids created by both RWPE-1 and PrEC 11220 cell lines (Fig. 2D). Spheroid production was seen in both cell lines and, hence, was independent of the immortalization method. The RWPE-1 cells were superior in forming a continuous and well-circumscribed layer of laminin-332 and continuous β4 integrin distribution as compared to the PrEC 11220 cells (Fig. 2D). The PrEC 11220 cells contained a punctate yet circumscribed distribution of β4 integrin, consistent with the dynamic processes expected when the basal lamina forms as directed by β4 integrin clustering on basal cells (Yurchenco, 2015). Taken together, the data suggest that both cell lines assemble laminin-332 and β4 integrin on the spheroid surface. The punctate distribution observed with PrEC 11220 spheroids suggests that it could be useful for tracking dynamic β4-integrin-directed assembly of the basal lamina. In contrast, RWPE-1 spheroids assembled a robust and tight laminin-332 and β4 integrin layer, which could be used as a stringent test for determining the influence of contextual signals on the invasive budding in HG-PIN. RWPE-1 spheroids contained functional luminal cells as increased PSA secretion could be detected in response to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) treatment compared to untreated controls (Fig. 2E,F).

Fig. 2.

3D morphogenesis of PIN arising from single cells. (A) RWPE-1 acini growth from a single cell after the indicated number of days (d) in culture. Scale bars: 20 µm. (B) A day-14 RWPE-1 spheroid stained for β-catenin (red), and ZO1 (green). Scale bar: 10 µm. (C) Quantification of the number of RWPE-1 spheroids with lumens on day 10. Data are mean±s.d. from three experiments, n=100. **P=0.0088 (two-tailed t-test). (D) Spheroids from RWPE-1 cells on day 14 (top row) and PREC 11220 cells on day 10 (bottom row) stained for with laminin-332 (L332, red), integrin β4 (red), HMWCK (green) and p63 (red). Scale bars: 10 µm. (E) Day-14 RWPE-1 spheroids without DHT (left) and with DHT (right) stained for cytokeratin 5 and 14 (CK, green) and PSA (red). Scale bars: 10 µm. (F) DHT treatment induces a twofold increase in PSA production as determined by a quantification of signal intensity for cytokeratin 5 and 14 distribution (green) and PSA distribution (red) across the images in E. The PSA intensity signal relative to cytokeratin signal is indicated by the size of double-headed arrow. (G) Single-plane images of day-10 spheroids. Staining for CEP135 (left panel, red) and α-tubulin (left panel, green) reveals the spindle orientation. The right-hand panel shows spheroids stained for α-tubulin (green), laminin-332 (red) and DNA (blue) to highlight spindle orientation relative to laminin-332. Note that cell division parallel to basement membrane (laminin-332) results in two cells that are located side by side, whereas cell division perpendicular to laminin-332 results in cells located in the lumen. Scale bars: 10 µm (main images), 1 µm (inset in top left). (H) Radial histograms (rose plots) showing mitotic spindle angle relative to the laminin-332 layer of dividing cells in RWPE-1 spheroids on day 10; n=33 spindles. Nuclei in all panels were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue).

We next measured the accuracy of mitotic spindle orientation in basal cells from RWPE-1 spheroids. The RWPE-1 spheroids were used as these have a highly ordered laminin-332 layer as a reference point. Mitotic spindles and spindle poles were visualized by staining for α-tubulin and the centriole protein CEP135; spindle orientation in basal cells was measured relative to laminin-332 deposition (Fig. 2G; Movie 3). Approximately 67% of mitotic spindles in basal cells were oriented parallel to or within 30° of the laminin-332 layer resulting in new cells that were side-by-side (Fig. 2H). The ability to measure the distribution of centrosomes and spindle orientation will allow testing of genetic, signaling and contextual determinants within basal cells that promote invasive human HG-PIN.

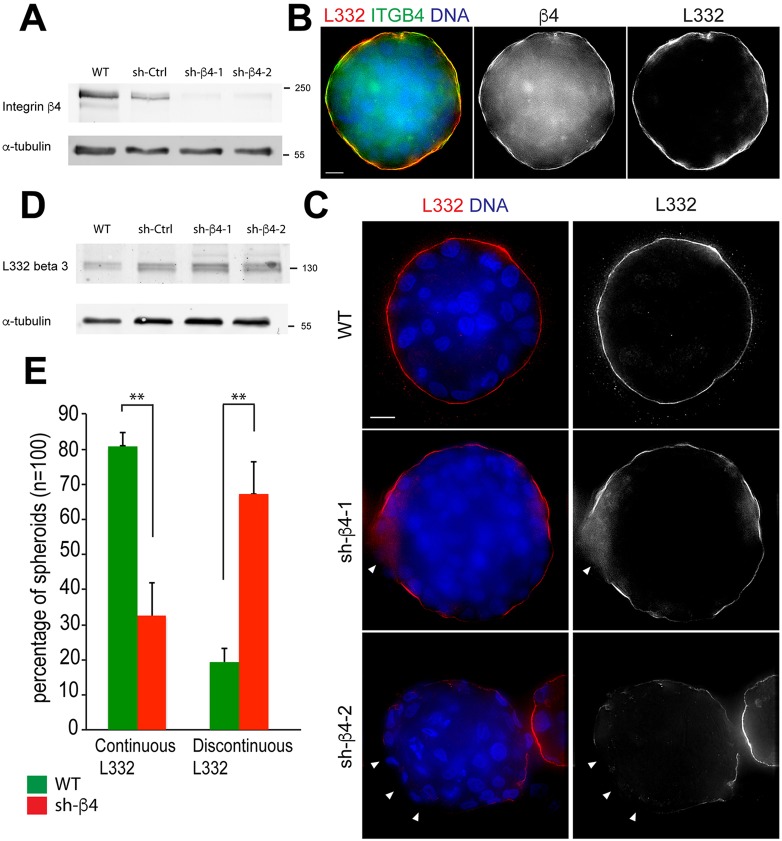

The absence of α6β4 integrin expression promotes an invasive PIN phenotype

We generated two stable RWPE-1 cell lines expressing one of two different short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to silence β4 integrin (sh-β4-1 and sh-β4-2) expression to test the transition to a HG-PIN phenotype. The RWPE-1 spheroids were used as these had a highly ordered laminin-332 layer that serves as a stringent test for determining the influence of β4 integrin depletion. Western blotting confirmed efficient depletion of β4 integrin (Fig. 3A). Spheroids made with β4-integrin-expressing cells displayed a continuous layer of laminin-332 co-distributing with β4 integrin [Fig. 3B,C, wild-type (WT)]. In contrast, depletion of β4 integrin resulted in a discontinuous layer of laminin-332 (Fig. 3C, sh-β4, arrowheads). As expected, β4 integrin depletion did not affect the abundance of laminin-332 (Dowling et al., 1996; Georges-Labouesse et al., 1996), as confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 3D). Approximately 65% of β4-integrin-depleted spheroids contained a discontinuous laminin-332 layer as compared to 19% of β4-integrin-containing control spheroids (Fig. 3E). β4 integrin depletion did not alter the ability of cells to form spheroids or produce laminin-332 but altered the organization of laminin-332, creating a discontinuous layer. We speculate that a discontinuous laminin-332 layer will disrupt normal glandular homeostasis and give rise to spindle misorientation to facilitate genomic instability, tissue disorganization, metastasis and expansion of cancer stem cell compartments (reviewed in Pease and Tirnauer, 2011). Therefore, this model can be used to determine whether mechanisms that disrupt laminin-332 continuity [whether it be defects of the essential adhesion receptor (β4 integrin), defective production of laminin-332 by the stroma or loss of normal basal cell layer by luminal expansion] will stimulate the HG-PIN process.

Fig. 3.

3D PIN Model – absence of α6β4 integrin expression and discontinuous laminin-332 layer. (A) Cell lysates from shRNA-expressing RWPE-1 cells were probed for β4 integrin and α-tubulin; the position of molecular mass markers is shown in kDa. (B) Day-10 WT RWPE-1 spheroids immunostained for laminin-332 (L332, red) and β4 integrin (β4, green) showing colocalization of laminin-332 and β4 integrin (yellow). (C) Day-10 RWPE-1 spheroids immunostained for laminin-332 (red) showing a continuous layer in WT RWPE-1 spheroids (top panel) and a discontinuous distribution of laminin-332 (white arrowheads) in β4 integrin-depleted spheroids (middle and bottom panels). DNA (blue). Scale bars: 10 µm. (D) Detection of the β3 chain of laminin-332 and α-tubulin in wild-type (WT), shRNA control (sh-Ctrl) and β4-integrin-depleted RWPE-1 lysates. (E) Percentage of continuous laminin-332 assembly in day-10 WT and β4 integrin-depleted spheroids. Data are mean±s.d. from three experiments, n=100. **P<0.001 (two-tailed t-test).

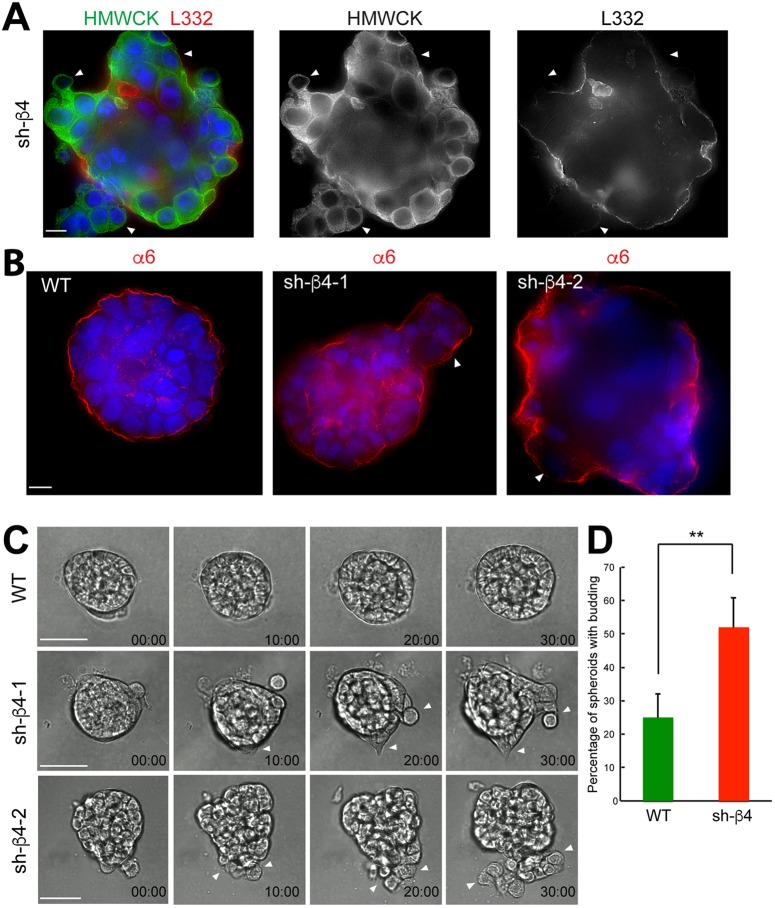

Given that discontinuities in the basement membrane can induce cell invasion and dissemination (Nguyen-Ngoc et al., 2012), we used live imaging of β4-integrin-depleted spheroids to investigate phenotypic changes. Strikingly, we observed prominent budding in β4-integrin-depleted spheroids in regions of a discontinuous laminin-332 layer that was not observed in controls (Fig. 4A; Movies 4–6). The budding spheroids contained α6 integrin on their surfaces (Fig. 4B), which in the absence of the β4 integrin subunit, is the α6β1 integrin. On day 10, budding of the epithelial cells was observed in β4-integrin-depleted spheroids (Fig. 4C) at a significantly higher level than in WT RWPE-1 spheroids (Fig. 4D). The loss of β4 integrin expression and persistence of α6β1 expression is consistent with the switching of the heterodimer composition during prostate cancer progression (Cress et al., 1995).

Fig. 4.

Active budding of basal cells through the discontinuous laminin-332 layer occurs in the absence of β4 integrin expression in RWPE-1 spheroids. (A) Day-10 β4 integrin-depleted (sh-β4) spheroid showing areas of budding (white arrowheads). Basal cells are immunolabeled for HMWCK (green) and the laminin-332 layer (L332, red). DNA, blue. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Day-10 WT and β4-integrin-depleted (sh-β4-1, sh-β4-2) spheroids. Cells were immunostained for α6 integrin (α6, red). Areas of budding are indicated by white arrowheads. DNA, blue. Scale bar: 10 µm. (C) Time series of WT (top row, Movie 4) and β4-integrin-depleted spheroids (middle and bottom rows, Movies 5 and 6) showing examples of active cell budding time stamps as hours:minutes. Scale bars: 40 µm. (D) Quantification of the percentage of spheroids with the invasive budding phenotype in WT and β4-integrin-depleted (sh-β4) spheroids. Data are mean±s.d. from three experiments, n=100. **P=0.0016 (two-tailed t-test).

Taken together, our data indicate that loss of β4 integrin expression generates laminin-332 continuity gaps through which basal cells exit the spheroid. The depletion of β4 integrin expression in normal prostate basal cells creates a new HG-PIN-type model that can be used to determine which microenvironmental or contextual cues, and somatic mutations, promote HG-PIN progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human tissue staining

Formalin-fixed de-identified human cancer tissues were stained using a Discovery XT Automated Immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ) in a core support service within the UA Cancer Center. The use of de-identified human tissue was in accordance with the guidelines and approval of the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained for all tissue donors and that all clinical investigations have been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Samples were imaged using an Olympus BX40 system (Southwest Precision Instruments, Tucson, Arizona, USA) with a 4× (NA 0.13) and 40× objective (NA 0.75).

Lentiviral vectors

The lentiviral vectors pGFP-C-shLenti shRNA-29 (Addgene, TL312080) containing a GFP reporter were used. Cells were infected with lentivirus containing the scrambled shRNA (Addgene, TR30022) as control, and shRNA hairpin against β4 integrin. Sequences of shRNAs are 5′-GUACAGCGAUGACGUUCUACGCUCUCCAU-3′ (sh-β4-1) and 5′-CCGUAUUGCGACUAUGAGAUGAAGGUGUG-3′ (sh-β4-2). Transfected cells were selected in 500 ng/ml puromycin and sorted by flow cytometry [BD Flow Machine FACSAria III; UACC Flow Cytometry shared resource (FCSR)] using the GFP signal.

Epithelial non-tumorigenic human prostate cells

RWPE-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, CRL11609TM), and were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Corning, cat. no. 10-016-CV), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum containing detectable levels of testosterone and corticosteroids (FBS, Seradigm, Lot 294R13), 100 IU penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin (MP Biomedicals, cat. no. 1674049). RWPE-1 identity was verified by assessing the allelic signature of 15 different genetic markers. Immortalized human PrEC 11220 cells were generously provided by John Isaacs (The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (Dalrymple et al., 2005; Salmon et al., 2000). These cells were immortalized by sufficient basal hTERT expression. The cells have a normal human male karyotype and grow in KSFM (Life Technologies, ref. 17005-075), 100 IU penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin (MP Biomedicals, cat. no. 1674049).

3D model staining and microscopy

For 3D culture, the RWPE-1 cells were maintained as described previously (Tyson et al., 2007). For DHT treatment, the medium was supplemented with 5 nM DHT (Sigma-Aldrich, D-073). Growth-factor-reduced matrigel (BD Biosciences, lot no.5173014) was used from a single lot with protein concentrations between 10 and 11 mg/ml. 3D indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (Debnath et al., 2002; Klebba et al., 2013). Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 6. Antibodies used were: anti-α-tubulin FITC-conjugated DM1a (1:100; Sigma F2168), anti-laminin-332 (1:200; Abcam ab14509), anti-ZO1 (1:200; Life Technologies ZO1-1A12), anti-β-catenin (1:100; Cell Signaling 9562), anti-β4 integrin (1:200; EPR 8558), anti-HMWCK (1:200; DAKO 34βE12), anti-p63 (1:100; Biorbyt orb214808), anti-PSA (1:100; Cell Signaling D6B1), anti-CEP135 (1:100; Abcam ab196809), and anti-α6 integrin (1:100; J1B5). For live-cell imaging, cells were grown on eight-well tissue culture Lab-Tek chambered coverglass (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 155411) for 3D imaging. Cells were imaged as above under optimal growth conditions. Images were captured every 15 min for 2–3 days.

Western blotting

Cell extracts were produced by lysing cells in cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% v/v Triton X-100, 1% w/v sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) as described previously (Klebba et al., 2013). Antibodies used included anti-β4 integrin (1:1000; EPR 8558), anti-laminin-332 (1:1000; Abcam ab14509), anti-α-tubulin (1:1000; Sigma DM1a) and IRDye 800CW secondary antibodies (1:1500; Li-Cor Biosciences).

Acknowledgements

The gift of the normal human prostate cell line (PrEC 11220) by John T. Isaacs is gratefully acknowledged. We thank the staff of the TACMASR for the tissue processing and staining and the FCSR service for cell sorting, Dan Buster for assistance with image analysis and Cynthia S. Rubenstein for assistance with 3D culture and time-lapse microscopy. We thank William L. Harryman for the editing assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

M.W., A.E.C. and G.C.R. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript; M.W. performed the experiments and R.B.N. and B.S.K. contributed pathology expertise.

Funding

This work was supported in part by competitively awarded grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (CA159406 to A.E.C. and P30 CA 23074). G.C.R. is grateful for support from NIH Search Results National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (R01GFM110166, MCB1158151), and the Phoenix Friends of the UA Cancer Center. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.188177.supplemental

References

- Bello D., Webber M. M., Kleinman H. K., Wartinger D. D. and Rhim J. S. (1997). Androgen responsive adult human prostatic epithelial cell lines immortalized by human papillomavirus 18. Carcinogenesis 18, 1215-1223. 10.1093/carcin/18.6.1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkhoff H. (1996). Role of the basal cells in premalignant changes of the human prostate: a stem cell concept for the development of prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 30, 201-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkhoff H. and Remberger K. (1996). Differentiation pathways and histogenetic aspects of normal and abnormal prostatic growth: a stem cell model. Prostate 28, 98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick D. G. (1996a). Progression of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia to early invasive adenocarcinoma. Eur. Urol. 30, 145-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick D. G. (1996b). Prospective origins of prostate carcinoma. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia. Cancer 78, 330-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick D. G., Pacelli A. and Lopez-Beltran A. (1996). Molecular biology of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Prostate 29, 117-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H. (2011). Extracellular matrix in development: insights from mechanisms conserved between invertebrates and vertebrates. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005082 10.1101/cshperspect.a005082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouly G., Abad P. C., Knowles D. W. and Lelievre S. A. (2007). The control of tissue architecture over nuclear organization is crucial for epithelial cell fate. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1596-1606. 10.1242/jcs.03439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cress A. E., Rabinovitz I., Zhu W. and Nagle R. B. (1995). The alpha 6 beta 1 and alpha 6 beta 4 integrins in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 14, 219-228. 10.1007/BF00690293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple S., Antony L., Xu Y., Uzgare A. R., Arnold J. T., Savaugeot J., Sokoll L. J., De Marzo A. M. and Isaacs J. T. (2005). Role of notch-1 and E-cadherin in the differential response to calcium in culturing normal versus malignant prostate cells. Cancer Res. 65, 9269-9279. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T. L., Cress A. E., Dalkin B. L. and Nagle R. B. (2001). Unique expression pattern of the alpha6beta4 integrin and laminin-5 in human prostate carcinoma. Prostate 46, 240-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath J., Mills K. R., Collins N. L., Reginato M. J., Muthuswamy S. K. and Brugge J. S. (2002). The role of apoptosis in creating and maintaining luminal space within normal and oncogene-expressing mammary acini. Cell 111, 29-40. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01001-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling J., Yu Q. C. and Fuchs E. (1996). Beta4 integrin is required for hemidesmosome formation, cell adhesion and cell survival. J. Cell Biol. 134, 559-572. 10.1083/jcb.134.2.559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekblom M., Falk M., Salmivirta K., Durbeej M. and Ekblom P. (1998). Laminin isoforms and epithelial development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 857, 194-211. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10117.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges-Labouesse E., Messaddeq N., Yehia G., Cadalbert L., Dierich A. and Le Meur M. (1996). Absence of integrin alpha 6 leads to epidermolysis bullosa and neonatal death in mice. Nat. Genet. 13, 370-373. 10.1038/ng0796-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner M. C., Weier C., Xu M. M., Vaghasia A., Gurel B., Gumuskaya B., Esopi D. M., Fedor H., Tan H.-L., Kulac I. et al. (2016). Molecular evidence that invasive adenocarcinoma can mimic prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and intraductal carcinoma through retrograde glandular colonization. J. Pathol. 238, 31-41. 10.1002/path.4628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggman M. J., Macoska J. A., Wojno K. J. and Oesterling J. E. (1997). The relationship between prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer: critical issues. J. Urol. 158, 12-22. 10.1097/00005392-199707000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J., Yang Y., McDaniel K. M., Dalkin B. L., Cress A. E. and Nagle R. B. (1996). Differential expression of laminin 5 (alpha 3 beta 3 gamma 2) by human malignant and normal prostate. Am. J. Pathol. 149, 1341-1349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. L. (2004). Epithelial stem cells in human prostate growth and disease. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 7, 188-194. 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata T., Schultz D., Hicks J., Hubbard G. K., Mutton L. N., Lotan T. L., Bethel C., Lotz M. T., Yegnasubramanian S., Nelson W. G. et al. (2010). MYC overexpression induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and loss of Nkx3.1 in mouse luminal epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 5, e9427 10.1371/journal.pone.0009427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthaus W. R., Iaquinta P. J., Drost J., Gracanin A., van Boxtel R., Wongvipat J., Dowling C. M., Gao D., Begthel H., Sachs N. et al. (2014). Identification of multipotent luminal progenitor cells in human prostate organoid cultures. Cell 159, 163-175. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebba J. E., Buster D. W., Nguyen A. L., Swatkoski S., Gucek M., Rusan N. M. and Rogers G. C. (2013). Polo-like kinase 4 autodestructs by generating its Slimb-binding phosphodegron. Curr. Biol. 23, 2255-2261. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaresan K., Kakkar N., Verma A., Mandal A. K., Singh S. K. and Joshi K. (2010). Diagnostic utility of alpha-methylacyl CoA racemase (P504S) & HMWCK in morphologically difficult prostate cancer. Diagn. Pathol. 5, 83 10.1186/1746-1596-5-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montironi R. and Schulman C. C. (1996). Precursors of prostatic cancer: progression, regression and chemoprevention. Eur. Urol. 30, 133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montironi R., Bostwick D. G., Bonkhoff H., Cockett A. T. K., Helpap B., Troncoso P. and Waters D. (1996a). Origins of prostate cancer. Cancer 78, 362-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montironi R., Pomante R., Diamanti L., Hamilton P. W., Thompson D. and Bartels P. H. (1996b). Evaluation of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia after treatment with a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor (finasteride). A methodologic approach. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 18, 461-470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera J.-M., Perner S., Genega E. M., Sanda M., Hofer M. D., Mertz K. D., Paris P. L., Simko J., Bismar T. A., Ayala G. et al. (2008). Characterization of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and potential clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 3380-3385. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera J.-M., Mehra R., Regan M. M., Perner S., Genega E. M., Bueti G., Shah R. B., Gaston S., Tomlins S. A., Wei J. T. et al. (2009). Prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer among men undergoing prostate biopsy in the United States. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 4706-4711. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle R. B. and Cress A. E. (2011). Metastasis update: human prostate carcinoma invasion via tubulogenesis. Prostate Cancer 2011, 249290 10.1155/2011/249290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle R. B., Petein M., Brawer M., Bowden G. T. and Cress A. E. (1992). New relationships between prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic carcinoma. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 16H, 26-29. 10.1002/jcb.240501207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle R. B., Knox J. D., Wolf C., Bowden G. T. and Cress A. E. (1994). Adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix, and proteases in prostate carcinoma. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 19, 232-237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle R. B., Hao J., Knox J. D., Dalkin B. L., Clark V. and Cress A. E. (1995). Expression of hemidesmosomal and extracellular matrix proteins by normal and malignant human prostate tissue. Am. J. Pathol. 146, 1498-1507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Ngoc K.-V., Cheung K. J., Brenot A., Shamir E. R., Gray R. S., Hines W. C., Yaswen P., Werb Z. and Ewald A. J. (2012). ECM microenvironment regulates collective migration and local dissemination in normal and malignant mammary epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2595-E2604. 10.1073/pnas.1212834109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease J. C. and Tirnauer J. S. (2011). Mitotic spindle misorientation in cancer–out of alignment and into the fire. J. Cell Sci. 124, 1007-1016. 10.1242/jcs.081406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petein M., Michel P., van Velthoven R., Pasteels J.-L., Brawer M. K., Davis J. R., Nagle R. B. and Kiss R. (1991). Morphonuclear relationship between prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancers as assessed by digital cell image analysis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 96, 628-634. 10.1093/ajcp/96.5.628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes-Junior J., Reis S. T., Dall'Oglio M., Neves de Oliveira L. C., Cury J., Carvalho P. A., Ribeiro-Filho L. A., Moreira Leite K. R. and Srougi M. (2009). Evaluation of the expression of integrins and cell adhesion molecules through tissue microarray in lymph node metastases of prostate cancer. J. Carcinog. 8, 3 10.4103/1477-3163.48453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen L. and Uitto J. (1998). Hemidesmosomal variants of epidermolysis bullosa. Mutations in the alpha6beta4 integrin and the 180-kD bullous pemphigoid antigen/type XVII collagen genes. Exp. Dermatol. 7, 46-64. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh M., Franco O. E., Hayward S. W., van der Meer R. and Abdulkadir S. A. (2008). A role for polyploidy in the tumorigenicity of Pim-1-expressing human prostate and mammary epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 3, e2572 10.1371/journal.pone.0002572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P., Oberholzer J., Occhiodoro T., Morel P., Lou J. and Trono D. (2000). Reversible immortalization of human primary cells by lentivector-mediated transfer of specific genes. Mol. Ther. 2, 404-414. 10.1006/mthe.2000.0141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz M., Moll R., Hesse U., Prasad A. R., Gandolfi J. A., Hasan S. R., Bartholdi M. and Cress A. E. (2005). Identification of a stem cell candidate in the normal human prostate gland. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 84, 341-354. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A. A. and Marker P. C. (2006). Branching morphogenesis in the prostate gland and seminal vesicles. Differentiation 74, 382-392. 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson D. R., Inokuchi J., Tsunoda T., Lau A. and Ornstein D. K. (2007). Culture requirements of prostatic epithelial cell lines for acinar morphogenesis and lumen formation in vitro: role of extracellular calcium. Prostate 67, 1601-1613. 10.1002/pros.20628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen A. P. M., Aalders T. W., Ramaekers F. C. S., Debruyne F. M. J. and Schalken J. A. (1988). Differential expression of keratins in the basal and luminal compartments of rat prostatic epithelium during degeneration and regeneration. Prostate 13, 25-38. 10.1002/pros.2990130104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen A. P., Ramaekers F. C., Aalders T. W., Schaafsma H. E., Debruyne F. M. and Schalken J. A. (1992). Colocalization of basal and luminal cell-type cytokeratins in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 52, 6182-6187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-S., Shankar S., Dhanasekaran S. M., Ateeq B., Sasaki A. T., Jing X., Robinson D., Cao Q., Prensner J. R., Yocum A. K. et al. (2011). Characterization of KRAS rearrangements in metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Discov. 1, 35-43. 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Lacoche S., Huang L., Xue B. and Muthuswamy S. K. (2013). Rotational motion during three-dimensional morphogenesis of mammary epithelial acini relates to laminin matrix assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 163-168. 10.1073/pnas.1201141110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber M. M., Bello D., Kleinman H. K. and Hoffman M. P. (1997). Acinar differentiation by non-malignant immortalized human prostatic epithelial cells and its loss by malignant cells. Carcinogenesis 18, 1225-1231. 10.1093/carcin/18.6.1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen K., Litjens S. H. M. and Sonnenberg A. (2006). Multiple functions of the integrin alpha6beta4 in epidermal homeostasis and tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2877-2886. 10.1128/MCB.26.8.2877-2886.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J., Swiercz J. M., Banon-Rodriguez I., Matkovic I., Federico G., Sun T., Franz T., Brakebusch C. H., Kumanogoh A., Friedel R. H. et al. (2015). Semaphorin-Plexin signaling controls mitotic spindle orientation during epithelial morphogenesis and repair. Dev. Cell 33, 299-313. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco P. D. (2015). Integrating activities of laminins that drive basement membrane assembly and function. Curr. Top. Membr. 76, 1-30. 10.1016/bs.ctm.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]