Abstract

Background:

Different definitions used for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) preclude getting reliable prevalence estimates. Study objective was to find the prevalence of COPD as per standard Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease definition, risk factors associated, and treatment seeking in adults >30 years.

Methodology:

Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Delhi, among 1200 adults, selected by systematic random sampling. Pretested questionnaire was used to interview all subjects and screen for symptoms of COPD. Postbronchodilator spirometry was done to confirm COPD.

Statistical Analysis:

Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was calculated by multivariable analysis to examine the association of risk factors with COPD. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was developed to assess predictability. Results: The prevalence of COPD was 10.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 8.5, 11.9%). Tobacco smoking was the strongest risk factor associated (aOR 9.48; 95% CI 4.22, 14.13) followed by environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), occupational exposure, age, and biomass fuel. Each pack-year of smoking increased 15% risk of COPD. Ex-smokers had 63% lesser risk compared to current smokers. Clinical allergy seems to preclude COPD (aOR 0.06; 95% CI 0.02, 0.37). ROC analysis showed 94.38% of the COPD variability can be assessed by this model (sensitivity 57.4%; positive predictive value 93.3%). Only 48% patients were on treatment. Treatment continuation was impeded by its cost.

Conclusion:

COPD prevalence in the region of Delhi, India, is high, and our case-finding population study identified a high rate of patients who were not on any treatment. Our study adds to creating awareness on the importance of smoking cessation, early diagnosis of COPD, and the need for regular treatment.

KEY WORDS: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epidemiology, prevalence, risk factors, treatment seeking behavior

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects 210 million people worldwide and kills > 4 million people every year, accounting for around 9% of total deaths. Ninety percent of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. It is projected to be the 3rd leading cause of death by 2030.[1] Its chronic nature causes disruption of normal social roles, reduced workability, and poses massive burden on direct and indirect costs.[2]

Different definitions used for COPD in epidemiological studies preclude getting a reliable prevalence estimate. Traditionally, in community-based studies, chronic bronchitis (CB) is used as a proxy to measure COPD owing to its relative ease of diagnosis. CB is defined as cough with expectoration occurring on most days for at least 3 months in a year for at least 2 consecutive years whereas, COPD is defined as this plus spirometric evidence of airway obstruction.[3]

According to the World Health Organization report, the prevalence of COPD ranges between 4% and 20% in the Indian adults.[1] According to a recent systematic review[4] which includes estimates from the INSEARCH and other major studies in India, the prevalence of CB seems to range between 6.5% and 7.7% in rural and up to 9.9% in urban India. The review also mentions that the included studies were mostly low quality, questionnaire-based and was conducted around 1990–2006. These figures may underestimate the true burden of COPD since questionnaire-based prevalence estimates tend to be lower than the true spirometry-based estimates.[5] This review provides the best available estimate of COPD prevalence till date but is unlikely to reflect the current disease burden across all Indian subpopulations.[4]

As the current prevalence of COPD in India is unclear, rigorous estimates are required using standard epidemiological methods, to develop optimal strategies for disease control. This study was planned to find the prevalence of COPD (using standard Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] definition),[3] associated risk factors, and treatment seeking behavior of the people living in Mehrauli, a large urban community in South Delhi, India, which is a field practice area of Lady Hardinge Medical College.

Methodology

Study design, period, and setting

The community-based cross-sectional study was conducted during January 2012 to June 2013, in Mehrauli, which comprise 8 wards (administrative units of the urban area) with a total population of 126,000 belonging mostly to lower middle and upper lower socioeconomic class (as per modified Kuppuswamy scale 2012).[6]

Case definition of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The diagnosis of COPD was based on symptoms and was confirmed by spirometry. Any subject having history of dyspnea or chronic cough or sputum production or exposure to risk factors (tobacco smoke, environmental tobacco smoke [ETS] exposure, biomass fuel use, occupational dusts, and family history of COPD) along with a postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1st second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity ratio <70% was confirmed as COPD.[3]

Sample size and sampling technique

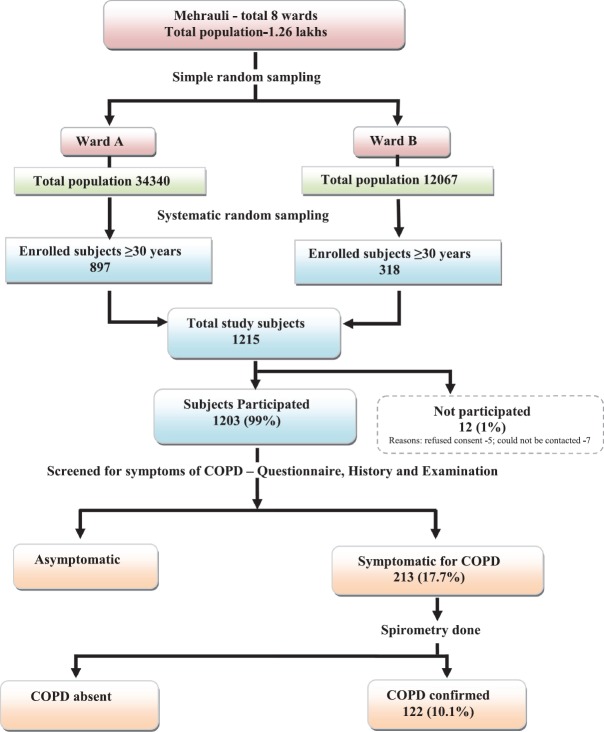

The study sample was calculated as 1200 adults, aged 30 years and above, considering 8% prevalence of COPD,[7] 20% relative error, desired confidence level 95%, and 10% nonresponse rate. Multistage sampling technique was used to select study subjects. In the first stage, two of the eight municipal wards (25%) were selected using a simple random technique (lottery method) with population of 34,340 (Ward A) and 12067 (Ward B), respectively. In next stage, proportionate samples, i.e., 897 and 318 from Ward A and B were enrolled. As ward wise line listing data of individuals and households were not available, systematic random sampling method was used to select the study sample. Household was the sampling unit. Initially, total households were estimated in the respective wards considering a family size of five (Census 2011). Sampling interval was calculated by dividing the total households by the sample required. Every 7th household was visited in both wards after selecting the first household randomly. All adults aged 30 years and above were interviewed in selected households [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Methodology

Study instrument

International Primary Care Airways Guidelines Questionnaire[8] for COPD was adapted and used in the study. It was validated by experts and pretested before using it for data collection. The questionnaire was designed to collect information regarding demographic profile, symptoms, risk factors, and treatment seeking for COPD.

A portable spirometer “Spirocheck” (Morgan & Co. Ltd., Rainham, Gillingham, Kent, England) was used for spirometry. The instrument was standardized and pilot tested in 25 new patients who presented with shortness of breath in outpatient department of the National Institute of TB and Respiratory Diseases (NITBRD), New Delhi, and was found to be 90% sensitive and 80% specific in diagnosing COPD as compared to pulmonary function laboratory results of the hospital.

Study procedure

Institutional ethics clearance was obtained (LHMC/ECHR/2014/289). Home visits were made to enroll 1215 individuals, of which 12 (1%) subjects either refused consent or could not be contacted; rest 1203 subjects were interviewed using the questionnaire. If a house was found locked, a second visit was made before excluding. Informed consent obtained from all participants after explaining study procedures in native language. The study was developed in a step-wise fashion. Community-dwelling subjects were randomly selected study subjects were interviewed with the COPD questionnaire first. Only in those with symptoms compatible with COPD, namely, dyspnea or wheeze or chronic cough or sputum production, pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry was done at the homes of the patients with the portable spirometer. The study investigator, trained in lung function assessment, performed spirometry in the field following the American thoracic Society and European Thoracic Society standards.[9] Separate mouthpiece was used for each subject. Subjects having difficulties performing spirometry in the field were escorted to NITBRD for spirometry.

Post study procedures

All chest symptomatics including patients of COPD were referred to NITBRD for checkup.

Operational definitions of risk factors

Smokers were classified into the current smoker (≥1 cigarette/beedi per day for the last 1 year), ex-smoker (stopped smoking or is taking <1 cigarette/beedi per day for the last 1 year) and nonsmoker (never smoked or has smoked <100 cigarette/beedi in lifetime).[10] Pack-years of smoking was calculated by multiplying number of packs of cigarettes/beedi smoked per day by the number of years the person smoked.[10]

Data on ETS exposure to one or more smoker at home or workplace and occupational exposure to dust, smoke, fumes, or gas in the workplace was obtained from a history of the duration (years) and regularity of exposure (≥4 days a week).

Clinical allergy was considered present if the subject had any recurrent history of coryza or skin rashes or eczema or itchiness of eyes in the past 12 months.

Overcrowding was defined by >2 persons per room or <110 sq. ft. area for 2 persons.[11] Doors or windows facing each other were considered to provide cross-ventilation.[11]

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS 17 software (Chicago: SPSS Inc.). Wherever applicable, descriptive analyses were done. To find out risk factors for COPD, adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was calculated by multivariate logistic regression. Risk factors found to be significant in univariate analysis at a level P < 0.25, were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was developed to assess the predictability of the model.

Results

Demographics

The mean age of the study participants was 46 ± 13 years. Among all study subjects, 647 (54%) were men and most belonged to the lower (46%) and middle (33%) socioeconomic class. Majority (86%) were literate, 45% of them were educated up to high school and above. Among men, 96% were employed; 80% of women were homemakers.

Risk factors

ETS exposure and occupational exposure to dust/fumes were recorded in 57% and 41% of study subjects respectively. There were 459 smokers (38%) of whom 65.5% smoked beedi, 27.8% cigarette, and 6.5% mixed (any combination of hookah/chillum with beedi or cigarette). The gender-wise distribution revealed 343/647 (53%) male and 116/556 (21%) female smokers. Thirty-one percent of the subjects used biomass as the primary fuel.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease burden

Out of 1203 study subjects, 213 (17.7%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 15.5, 19.9) had symptoms suggestive of COPD, and 122/1203 subjects had spirometry-confirmed COPD. The prevalence of COPD was 10.1% (95% CI 8.5, 11.9) of which 2.1% had mild (95% CI 1.3, 3.1; 25 subjects), 6.2% moderate (95% CI 4.9, 7.7; 75 subjects) and 1.8% severe COPD (95% CI 1.1, 2.7; 22 subjects) as per the GOLD guidelines.[3] COPD was highest prevalent in >70 years age group (35.6%). More men had COPD compared to women (men: women ratio 1.83). It was also more common in the lower socioeconomic class and in those living in overcrowded households [Table 1]. Table 2 shows proportion of COPD to be statistically higher (P < 0.05) in current smokers, those exposed to more pack-years of tobacco smoke, mixed smokers, those exposed to ETS or having an occupational exposure to dust/fumes/smoke for longer duration, subjects using biomass fuels, and subjects with no history of clinical allergy.

Table 1.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to sociodemographic and environmental factors

| n | COPD, n (%) | Statistical correlates (P)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | |||

| Age in years | |||

| 30–39 | 439 | 12 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| 40–49 | 356 | 16 (4.5) | |

| 50–59 | 172 | 20 (11.6) | |

| 60–69 | 135 | 38 (28.1) | |

| ≥70 | 101 | 36 (35.6) | |

| Total | 1203 | 122 (10.1) | |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 647 | 79 (12.2) | 0.013 |

| Women | 556 | 43 (7.7) | |

| Socioeconomic status# | |||

| Upper | 244 | 12 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Middle | 407 | 32 (7.8) | |

| Lower | 552 | 78 (14.1) | |

| Environmental factors | |||

| Cross ventilation | 0.09 | ||

| Present | 429 | 35 (8.2) | |

| Absent | 774 | 87 (11.2) | |

| Overcrowding | |||

| Present | 349 | 56 (16.0) | <0.001 |

| Absent | 854 | 66 (7.7) |

Upper and upper middle class was clubbed as “upper,” lower middle was named as “middle,” upper lower and lower was clubbed as “lower” because of fewer numbers in the extreme groups. *Chi-square test was used, #Kuppuswamy scale, 2012 was used. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 2.

Distribution of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to different risk factors

| Risk factors | n | COPD, n (%) | Statistical correlates (P)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main fuel use | |||

| Biomass fuel | 379 | 67 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| LPG | 824 | 55 (6.7) | |

| Smoking pattern | |||

| Current smoker | 325 | 81 (24.9) | <0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 134 | 29 (21.6) | |

| Nonsmoker | 744 | 12 (1.6) | |

| Substance smoked | |||

| Beedi only | 301 | 68 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| Cigarette only | 128 | 17 (13.3) | |

| Mixed | 30 | 25 (83.3) | |

| Quantity of tobacco smoke exposure (pack years) | |||

| No exposure | 744 | 12 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| ≤10 | 248 | 21 (8.5) | |

| 11–20 | 134 | 33 (24.6) | |

| >20 | 77 | 56 (72.7) | |

| Duration of ETS exposure (in years) | |||

| No exposure | 517 | 4 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| ≤10 | 229 | 7 (3.1) | |

| 11–19 | 94 | 16 (17.0) | |

| ≥20 | 363 | 95 (26.2) | |

| Duration of occupational exposure to dust/fumes (in years) | |||

| No exposure | 706 | 28 (4.0) | <0.001 |

| ≤10 | 190 | 8 (4.2) | |

| 11–19 | 66 | 12 (18.2) | |

| ≥20 | 241 | 74 (30.7) | |

| Family history of chronic airway disease | |||

| Present | 218 | 14 (6.4) | 0.052 |

| Absent | 985 | 108 (10.9) | |

| Clinical allergy | |||

| Present | 108 | 2 (1.9) | 0.01 |

| Absent | 1095 | 120 (10.9) |

*Chi-square test was used. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LPG: Liquid petroleum gas, ETS: Environmental tobacco smoke

Association with risk factors

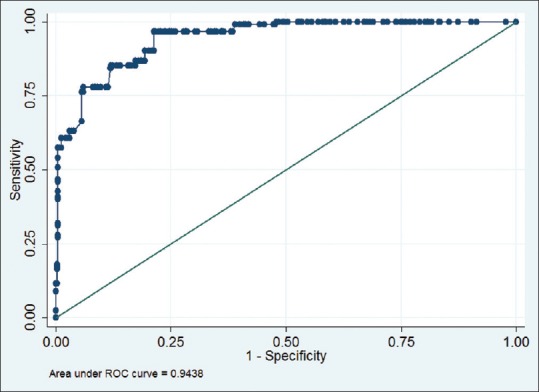

In multiple logistic regression model, age (>50 years), smoking, ETS, occupational exposure to dust/smoke, biomass fuel use, and absence of clinical allergy were found to be independent risk factors associated with COPD. The maximum risk was associated with smoking (aOR 9.5; 95% CI 4.2, 14.1) [Table 3]. ROC curve showed that 94.38% (95% CI 92.60, 96.16) of the variability of COPD can be assessed by this model with a sensitivity of 57.38% and positive predictive value (PPV) of 93.33% [Figure 2].

Table 3.

Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and risk factors

| Factors | COPD, OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Age in years | ||

| 30–≤50 | Reference | Reference |

| >50 | 8.20 (5.27–12.75)* | 4.19 (2.82–7.84)* |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 1.65 (1.12–2.45)* | 0.83 (0.45–1.54) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Upper | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 1.65 (0.83–3.27) | 0.77 (0.30–1.97) |

| Lower | 3.18 (1.69–5.96)* | 0.98 (0.38–2.64) |

| Cross ventilation | ||

| Present | Reference | - |

| Absent | 0.71 (0.47–1.06) | |

| Overcrowding | ||

| Absent | Reference | Reference |

| Present | 2.28 (1.55–3.34)* | 1.04 (0.59–1.81) |

| Main fuel use | ||

| LPG | Reference | Reference |

| Biomass | 3.01 (2.05–4.39)* | 2.64 (1.48–4.71)* |

| Smoking status | ||

| Nonsmoker | Reference | Reference |

| Ex-smoker | 18.35 (9.13–36.88)* | 4.15 (2.01–9.45)* |

| Current smoker | 19.59 (10.49–36.59)* | 9.48 (4.22– 14.13)* |

| ETS exposure | ||

| Absent | Reference | Reference |

| Present | 6.64 (3.31–9.76)* | 7.97 (3.32– 13.18)* |

| Occupational exposure | ||

| Absent | Reference | Reference |

| Present | 5.64 (3.64–8.76)* | 6.16 (3.30– 10.22)* |

| History of clinical allergy | ||

| Absent | Reference | Reference |

| Present | 0.15 (0.04–0.63)* | 0.06 (0.02–0.37)* |

| Family history of chronic airway diseases | ||

| Absent | Reference | Reference |

| Present | 1.79 (1.01–3.19)* | 1.19 (0.52–2.75) |

*Statistically significant, i.e., P<0.05. Only factors statistically significant in univariate analysis at a level P<0.25 are included in the multivariate analysis model. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LPG: Liquid petroleum gas, ETS: Environmental tobacco smoke, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of the multivariate model to predict chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (All factors significant in univariate analysis were used to create the model). Area under receiver operating characteristic curve 0.9438 (0.9260–0.9616), P < 0.001; model sensitivity: 57.38%, positive predictive value: 93.33%

Current or ex-smokers who smoked >20 pack-years had highest risk for COPD compared to those who smoked <10 pack-years [Table 4]. Each pack-year of smoking increased 15% (aOR 1.15; 95% CI 1.09, 1.22) risk of COPD. Ex-smokers had 63% lesser risk (aOR 0.37; 95% CI 0.19, 0.74) of COPD compared to current smokers (not shown in table). Mixed smokers had higher odds (OR 3.10; 95% CI 2.01, 4.19) for COPD compared to beedi smokers; however, there was no difference between beedi and cigarette smokers. The odds of having COPD was 5.8 and 6.9, respectively if exposed to ETS or occupational smoke for >20 years compared to those exposed for <10 years.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis showing dose-response relationship between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and risk factors^

| Duration of exposure (years) | Adjusted, OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current smokers# | Ex-smokers# | ETS exposure | Occupational exposure | |

| ≤10 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 11–20 | 4.87 (1.70–9.13)* | 0.34 (0.68–1.69) | 4.98 (1.76–14.06)* | 2.52 (0.86–7.44) |

| >20 | 12.95 (3.71–19.82)* | 2.43 (1.31–3.55)* | 5.82 (1.67–20.24)* | 6.91 (1.80–9.85)* |

^ For the sub groups, analysis was done after adjusting for all other factors significant in univariate analysis, *P<0.05, #Duration of exposure measured in pack-years of smoking. ETS: Environmental tobacco smoke, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

Treatment seeking behavior

Among patients with COPD, currently, 48% (58/122 patients) were on medical treatment, 41% (50/122) on home remedies and the rest 11% (14/122) never took any treatment. Among patients on medical treatment, around two-third (39/58) preferred government facility while the rest (19/58) availed private treatment. Steam inhalations, hot tea with ginger, and vicks inhaler were the common home remedies used. Discontinuation of treatment was seen in 10.6% patients (13/122). Long disease duration and costly medications were the major reason for discontinuation. The major reasons for never taking treatment were milder disease, unaffordable medications, and lack of family support.

Discussion

Key findings

In the current study, the prevalence of COPD in adults was 10.1% (95% CI 8.5, 11.9). Tobacco smoking was the strongest risk factor followed by ETS exposure, occupational exposure, age > 50 years, and biomass fuel use. Treatment seeking behavior was poor for COPD and cost of treatment seems to impede with treatment continuation.

Interpretation and limitations

Different definitions to diagnose COPD produces varied prevalence estimates.[12] It has been observed that using questionnaire method alone gives a lower estimate of COPD burden than using the spirometry-based criteria.[5,13] Spirometry is more specific to diagnose COPD because of its ability to identify patients with a definite airway obstruction but is difficult to perform in field.[14,15,16] In the current study, spirometry was limited only in those having symptoms suggestive of COPD. Although spirometry has been used for diagnosis, there remains a possibility that a minor fraction of the study subjects with symptoms and spirometry results compatible with COPD may have a differential diagnosis of asthma and/or bronchiectasis which could not be ruled out and was beyond the scope of this study.

Estimates from an analysis by Murthy and Sastry[17] and multicentric INSEARCH (questionnaire based) study[18] in 2004-2005 suggested that the prevalence of COPD in India varies region wise and may average around 5% in adults. Subsequently, in 2009, a spirometry-based study[16] in Mysore reported higher prevalence of COPD, i.e., 7.1% in adults 40 years and above. A recent systematic review (2012) reported the prevalence rates of COPD in adults up to 9.9% in urban India.[4] The higher prevalence in the current study (10.1%) may be due to methodological difference, higher number of smokers in the community, and actual increase in disease burden over time.

In the current study, the aged (>50 years) had more severe disease whereas the young had milder forms. This pattern is explained by the physiological decrease in FEV1 with age where the slope becomes steeper when aggravated by risk factors, particularly smoking. Genderwise, COPD, traditionally is more prevalent in males,[19] however in the current study, there was no significant difference between the sexes, may be because of higher proportion of female smokers (21%) in the study population.

Smoking has been irrefutably established to be the most important cause of COPD in several major international reports, was also found in our study.[10,20] We observed that odds of having COPD was nine and 4 times in the current and ex-smokers, respectively compared to the nonsmokers, which is similar to the findings of Shahab et al.[21] In our subgroup analysis among smokers, we had two key findings: (a) higher the dose more the risk, i.e., each pack-year of smoking added 15% risk for COPD and (b) 60% lesser risk of COPD in the ex compared to current smokers. These findings have important public health implications and highlight the need for stringent smoking cessation program for disease control. Pertaining to substance smoked, much alike to the study by Jindal et al.,[18] it seems that COPD was highest in mixed smokers, probably because of the higher dose of tobacco inhalation associated with mixed smoking.

Similar to the previous studies,[18,22,23] significant association was observed between biomass fuel use, ETS exposure and occupational exposure with COPD, which explains the occurrence of disease in nonsmokers. ETS exposure, in the current study, was a stronger risk factor than biomass fuel use. Inspite of our limitation to quantify precisely the exposures related to biomass fuels, ETS and occupational exposure, our subgroup analysis revealed that longer duration of exposure increases the risk for COPD. From our results, it seems that clinical allergy precludes COPD. In case of such history, reevaluation, and different diagnosis may be explored.

High PPV of the model indicates that, among those having all risk factors, chances of having COPD are as high as 90%. However, the comparatively low sensitivity implies that among subjects having COPD, 57% will have these risk factors. Thus, we can say, the risk factors are precisely good to predict COPD, but the vice versa is not always true. There may be some other factors associated which we have not captured. This is a limitation and needs further exploration.

Data regarding health seeking behavior in COPD patients is limited. The current study findings suggest that treatment seeking is rather poor in the patients of COPD where less than half of the patients were on treatment. Due to repeated and long-term treatment, the costs are unaffordable for many. Measures need to be taken for making medications available for the needful.

Conclusion

To prevent COPD and its consequences, the community should be educated about COPD, importance of smoking cessation and prohibition of smoking in public places to reduce ETS exposure.

At primary care level, identifying current smokers early and intensive individual level interventions to refrain them from smoking is necessary.[24,25,26] The societal-economic burden of COPD far out-weights the costs of active case finding through spirometric assessment of at-risk smokers in primary care.[27,28] Health-care resources can be maximized by training physicians in management and health workers in timely referral. To conclude, the health planners must spearhead the paradigm change toward “Preventive Healthcare” - lead our fight against COPD to develop and implement strategies for control.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Manish K Goel, Lady Hardinge Medical College and Dr. Ravi P Upadhyay, VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital for their help at various stages of this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Surveillance, Prevention and Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases: A Comprehensive Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JL, Campbell AC, Bowers M, Nichol AM. Understanding the social consequences of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The effects of stigma and gender. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:680–2. doi: 10.1513/pats.200706-084SD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Updated. 2015. [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 30]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.it/materiale/2015/GOLD_Report_2015.pdf .

- 4.McKay AJ, Mahesh PA, Fordham JZ, Majeed A. Prevalence of COPD in India: A systematic review. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:313–21. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rycroft CE, Heyes A, Lanza L, Becker K. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A literature review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:457–94. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S32330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic scale: Updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:103–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radha TG, Gupta CK, Singh A, Mathur N. Chronic bronchitis in an urban locality of New Delhi – an epidemiological survey. Indian J Med Res. 1977;66:273–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sichletidis L, Spyratos D, Papaioannou M, Chloros D, Tsiotsios A, Tsagaraki V, et al. A combination of the IPAG questionnaire and PiKo-6® flow meter is a valuable screening tool for COPD in the primary care setting. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20:184–9. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Guidelines for Controlling and Monitoring the Tobacco Epidemic: World Health Organization. 1998. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 24]. Available from: http://www.thl.fi/publications/ehrm/product1/section7.htm .

- 11.Park K. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 22nd ed. Jabalpur, India: Banarsidas Bhanot; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celli BR, Halbert RJ, Isonaka S, Schau B. Population impact of different definitions of airway obstruction. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:268–73. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00075102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Maturu VN, Dhooria S, Prasad KT, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Joint recommendations of Indian Chest Society and National College of Chest Physicians (India) Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2014;56:5–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gillespie S, Burney P, Mannino DM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): A population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370:741–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menezes AM, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, Muiño A, Lopez MV, Valdivia G, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): A prevalence study. Lancet. 2005;366:1875–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahesh PA, Jayaraj BS, Prahlad ST, Chaya SK, Prabhakar AK, Agarwal AN, et al. Validation of a structured questionnaire for COPD and prevalence of COPD in rural area of Mysore: A pilot study. Lung India. 2009;26:63–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.53226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murthy KJ, Sastry JG. Economic Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health Background Papers – Burden of Disease in India. 2005. [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/macrohealth/action/NCMH_Burden%20of%2disease (29%20Sep%202005).pdf .

- 18.Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Chaudhry K, Chhabra SK, D’souza GA, Gupta D, et al. A multicentric study on epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its relationship with tobacco smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soriano JB, Maier WC, Egger P, Visick G, Thakrar B, Sykes J, et al. Recent trends in physician diagnosed COPD in women and men in the UK. Thorax. 2000;55:789–94. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.9.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy KS, Gupta PC. Report on Tobacco Control in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahab L, Jarvis MJ, Britton J, West R. Prevalence, diagnosis and relation to tobacco dependence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a nationally representative population sample. Thora×. 2006;61:1043–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orozco-Levi M, Garcia-Aymerich J, Villar J, Ramírez-Sarmiento A, Antó JM, Gea J. Wood smoke exposure and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:542–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00052705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakke PS, Baste V, Hanoa R, Gulsvik A. Prevalence of obstructive lung disease in a general population: Relation to occupational title and exposure to some airborne agents. Thorax. 1991;46:863–70. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.12.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James AL, Palmer LJ, Kicic E, Maxwell PS, Lagan SE, Ryan GF, et al. Decline in lung function in the Busselton health study: The effects of asthma and cigarette smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:109–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-230OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pride NB. Smoking cessation: Effects on symptoms, spirometry and future trends in COPD. Thora×. 2001;56(Suppl 2):ii7–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson D, Adams R, Appleton S, Ruffin R. Difficulties identifying and targeting COPD and population-attributable risk of smoking for COPD: A population study. Chest. 2005;128:2035–42. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Britton M. The burden of COPD in the U.K.: Results from the confronting COPD survey. Respir Med. 2003;97(Suppl C):S71–9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Schayck CP, Chavannes NH. Detection of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;39:16s–22s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00040403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]