Abstract

Acute limb ischemia and peripheral vascular disease (PVD) are unusual presentations of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). Here, we present a case with PVD of both lower limbs leading to foot claudication. Digital subtraction angiography showed narrowing, irregularity, and occlusion of both lower limb arteries with no involvement of the abdomen visceral arteries. Based on significant weight loss, diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg, myalgia, testicular pain, and angiographic abnormalities in medium-sized arteries, he was diagnosed as having PAN. He was treated with corticosteroid and bolus intravenous cyclophosphamide following which he had prompt and near-complete recovery of the symptoms without any tissue loss.

KEY WORDS: Acute limb ischemia, angiography, peripheral vascular disease, polyarteritis nodosa

Introduction

Premature peripheral vascular disease (PVD) before 25 years of age is extremely rare. There is lack of epidemiological studies characterizing its prevalence, causes, and approach. There are few reports of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) presenting as PVD,[1,2] symmetrical peripheral gangrene,[3] and acute limb ischemia.[4] We report a young man who presented as PVD with acute-on-chronic limb ischemia who was finally diagnosed with PAN. He was treated with immunosuppression and had near-complete recovery of the symptoms, preventing gangrene, or amputation of the involved limbs.

Case Report

A 21-year-old man presented with fever, weight loss of 6 kg, myalgia, and polyarthralgia for 3 months. There was no response to anti-inflammatory drugs. He had a good relief of symptoms with an oral medication (possibly steroids) for 2 months, but as soon as he stopped it; a month ago, he developed additional symptoms of cramp and pain in both feet while walking. The pain used to subside with rest but used to recur again on walking the same distance, suggestive of claudication. His sleep was disturbed due to burning pain in both the forefeet, which used to decrease on dangling the feet but used to increase on raising the legs. The symptoms had markedly increased for last 10 days with continuous burning pain, coldness of feet, and inability to walk.

At this time, he presented to the emergency department of our hospital. His blood pressure at presentation was 150/100 mmHg. Both feet were cold, pale, and had absent pulses (bilateral posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis). There were few skin infarcts on the left sole. There was no toe gangrene. He was a nonsmoker and had no history of oral or genital ulcers. He had a history of left testicular pain 20 days back which lasted for 2 days. During that period, minimal free fluid was present in tunica vaginalis on ultrasound. The pain subsided spontaneously and did not recur.

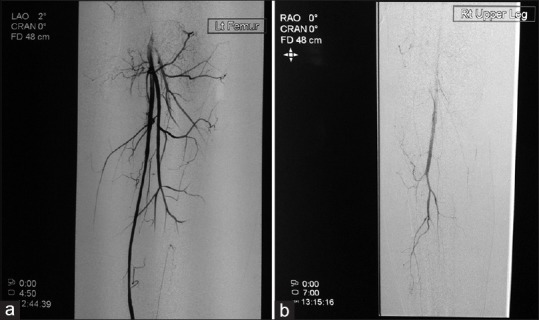

Thus, the patient had constitutional symptoms that responded to corticosteroids. This was followed by a subacute involvement of distal arteries of both the lower limbs manifesting as foot claudication. He finally presented to us with an episode of acute on chronic limb ischemia. Doppler ultrasound of the lower limbs arterial system showed complete occlusion of anterior and posterior tibial and peroneal arteries in both the legs with multiple collateral channels. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the lower limbs and abdomen visceral arteries showed symmetrical narrowing and irregularity of the mid and distal part of superficial femoral artery [Figure 1a] and popliteal artery with delayed contrast opacification, narrowing and occlusion of anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries on both sides [Figure 1b]. There was no aneurysm or stenosis of abdomen visceral arteries. Based on 1990 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria,[5] the diagnosis of PAN was made. He was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g daily) pulse for three consecutive days and had a marked relief in pain by the 2nd day. He had a gradual resolution of other symptoms and started walking by the end of a week. Urine examination was normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 61 mm at 1 h, C-reactive protein was 21.4 mg/dl, and platelet count was increased to 419,000/m2. Antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antiproteinase-3, and antimyeloperoxidase antibodies were negative. Serum complements were normal. Hepatitis-B surface antigen, antihepatitis-C antibody, and HIV by ELISA were also negative. Further, he was treated with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide and oral prednisolone as per the EUVAS protocol.[6] He had no tissue loss of the toes and his claudication pain subsided. The skin infarcts healed with a scar. He was followed up regularly and was in remission on azathioprine. Prednisolone was tapered and stopped after 1 year.

Figure 1.

Digital subtraction angiography of both the lower limbs showed normal proximal femoral artery with narrowing and irregularity of distal femoral and popliteal arteries (a) and complete occlusion of three main leg arteries, anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal artery (b)

Discussion

The first modern case of vasculitis was described in 1866 based on autopsy findings of grossly visible nodules in medium-sized vessels and was given the name of “periarteritis nodosa.”[7] The Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) revision (1994) of vasculitis nomenclature defined PAN as necrotizing inflammation of medium-sized or small arteries without glomerulonephritis or vasculitis involving arterioles, capillaries, or venules, differentiating it from microscopic polyangiitis. The incidence of PAN as per CHCC definition is 0.9/million/annum (between 0 and 1.7) and prevalence is 2–9/million.[8] The American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for PAN (1990) is one of the most widely used classification criteria.[5] Criteria includes weight loss >4 kg, livedo reticularis, testicular pain, myalgias, mononeuropathy, diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg, elevated creatinine 1.5 mg/dl, hepatitis-B virus, arteriographic abnormalities, and biopsy of small or medium-sized arteries showing polymorphonuclear cells. The present case satisfied five out of ten criteria thus classifying the vasculitis as PAN with sensitivity and specificity >80%. Magnetic resonance angiography can miss microaneurysms in visceral arteries, so DSA is the preferred mode of imaging of arteries in PAN. As the patient satisfied, the criteria for the diagnosis, muscle, or nerve biopsy were not done.

PAN typically presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, weight loss, myalgia, and arthralgia in combination with single or multiorgan manifestations resulting from ischemia or infarction. There are few case reports of PAN presenting as PVD and limb vessel involvement.[1,2,3,4] Similar to our case, the case reported by De Golovine et al.[1] had lower limb ischemia and bilateral femoral artery involvement. He was misdiagnosed as premature PVD secondary to tobacco use and hyperlipidemia. He was not given immunosuppression, the disease progressed and he succumbed to mesenteric ischemia. Diagnosis of PAN was made on autopsy. In contrast, due to rapid institution of immunosuppressive therapy, our case had a good outcome. Thus, in a patient with premature PVD common causes such as family history of premature atherosclerosis, smoking, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercoagulable states need to be categorically ruled before thinking of primary vasculitis as they are more common.[2] Héron et al. reported a 33-year-old hypertensive woman presenting with acute occlusion of the three infrapopliteal arteries of the right leg that led to the diagnosis of PAN.[4] She also had microaneurysms involving both renal arterial beds. The symptoms improved with corticosteroid therapy without anticoagulants or vascular intervention. This case was similar to the present case as both had good response to immunosuppression without the use of anticoagulants, thrombolytic drugs, or surgical interventions. Thus, the common presentations of PAN involving limb vessels vary from intermittent claudication[1] to Raynaud's phenomenon,[3] symmetrical peripheral gangrene,[3] and acute limb ischemia.[4]

Intermittent foot claudication is a less frequently reported symptom in literature compared to commonly cited leg claudication. This results from chronic occlusion of nutrient arteries supplying the plantar muscles with poor collateral circulation.[9] The causes for foot claudication documented in literature are dorsalis pedis entrapment due to anatomical variation[10] and medium vessel vasculitis such as Buerger's disease.[9] The exact mechanism by which PAN leads to PVD has not been specifically studied. However, it can be speculated that the arterial wall inflammatory infiltrate and proliferation of the cells therein leads to thickening of the wall and progressive narrowing of the lumen. This results in compromised blood flow to the group of muscles. In the present case, foot claudication was most likely due to the chronic arteritis of the nutrient vessels. The endothelial damage and turbulent blood flow secondary to arteritis can activate the coagulation cascade and thus can cause thrombosis of the involved vessel. This may be the reason for complete luminal occlusion and final presentation as acute lower limb ischemia.

Acute arterial occlusion is characterized by the sudden onset of excruciating pain, which may be associated with cold limbs, reduced or absent pulses, cyanosis, hyperesthesia, and paresis. The main differential diagnosis in a young patient is acute vasculitic neuropathy. Peripheral nerve involvement is frequent in PAN and is seen in 55%–79% of the patients.[11] Mononeuritis multiplex or asymmetric polyneuropathy is commonly seen. The rapid progression of mononeuritis multiplex can be confused with polyneuropathy. A distal, symmetrical polyneuropathy-like presentation is rare in vasculitis.[11] In acute arterial ischemia without obvious cyanosis or gangrene, the differentiation can sometimes be difficult. The burning sensation and paresis are common to both. Cold pale feet with the absence of pulses suggest arterial involvement. In addition, the presence of skin infarcts points to vessel involvement. Complex regional pain syndrome can be an important differential in unilateral limb ischemia.

Angiographic findings are present in about 40%–90% of patients. The most common arteries involved are mesenteric (33%–36%) and renal (11%–66%). A study reviewed positive angiograms in 56 consecutive patients with diagnosis of PAN.[12] The most frequent finding was occlusive arterial lesions. Only one patient had exclusive aneurysmal lesions (aneurysms or ectasia), 22 (39%) had only occlusive lesions (luminal irregularities resulting in reduction of caliber, stenosis, or occlusion), and rest 33 (59%) had mixed aneurysmal and occlusive lesions. Angiographic evaluation of extremities was done in 9/56 (16%) patients to evaluate symptoms limited to extremities. Aneurysms were detected in five patients in the arteries of skeletal muscles although occlusive disease was the usual angiographic finding. Upper extremity was involved in all nine patients while lower extremity involvement was seen in four patients. The presence of aneurysm is specific for PAN (90%), but its absence does not rule out the disease. Total abdominal angiography will pick up most cases of PAN but in cases with normal abdomen angiograms and strong suspicion of PAN, angiograms directed to the symptomatic limbs may help in documenting the angiographic abnormalities and diagnosis of PAN.

Thus, PAN presenting as PVD with normal visceral artery angiogram and involvement of the lower limb arteries is an unusual presentation. Vasculitic neuropathy and other differential diagnosis should be considered. Acute thrombosis of inflamed and narrowed arteries can lead to acute on chronic limb ischemia. Awareness of autoimmune primary vasculitis presenting as acute limb ischemia can lead to prompt use of immunosuppression and can salvage the ischemic limb. Anticoagulant drug therapy and vascular surgeries may not be helpful in such cases.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to the patient for the consent.

References

- 1.De Golovine S, Parikh S, Lu L. A case of polyarteritis nodosa presenting initially as peripheral vascular disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1528–31. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celecova Z, Krahulec B, Lizicarova D, Gaspar L. Vasculitides as a rare cause of intermittent claudication. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2013;114:353–6. doi: 10.4149/bll_2013_076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ninomiya T, Sugimoto T, Tanaka Y, Aoyama M, Sakaguchi M, Uzu T, et al. Symmetric peripheral gangrene as an emerging manifestation of polyarteritis nodosa. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:440–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Héron E, Fiessinger JN, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting as acute leg ischemia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1344–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lightfoot RW, Jr, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Zvaifler NJ, McShane DJ, et al. The American college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1088–93. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukhtyar C, Guillevin L, Cid MC, Dasgupta B, de Groot K, Gross W, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of primary small and medium vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:310–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.088096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Gay MA, García-Porrúa C. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:729–49. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, Bacon PA, Churg J, Gross WL, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:187–92. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirai M, Shinonoya S. Intermittent claudication in the foot and Buerger's disease. Br J Surg. 1978;65:210–3. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800650320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith BK, Engelbert T, Turnipseed WD. Foot claudication with plantar flexion as a result of dorsalis pedis artery impingement in an Irish dancer. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:212–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaublin GA, Michet CJ, Jr, Dyck PJ, Burns TM. An update on the classification and treatment of vasculitic neuropathy. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:853–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanson AW, Friese JL, Johnson CM, McKusick MA, Breen JF, Sabater EA, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa: Spectrum of angiographic findings. Radiographics. 2001;21:151–9. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja16151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]