Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate heat tolerance using heat tolerance indices, physiological, physical, thermographic, and hematological parameters in Santa Ines and Morada Nova sheep breeds in the Federal District, Brazil.

Methods

Twenty-six adult hair sheep, one and a half years old, from two genetic groups (Santa Ines: 12 males and 4 females; Morada Nova: 7 males and 3 females) were used and data (rectal temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, skin temperatures; hematological parameters) were collected during three consecutive days, twice a day (morning and afternoon), with a total of six repetitions. Also physical parameters (biometric measurements, skin and hair traits) and heat tolerance indices (temperature-humidity index, Iberia and Benezra) were evaluated. The analyses included analyses of variance, correlation, and principal components with a significance level of 5%.

Results

The environmental indices, in general, indicate a situation of thermal discomfort for the animals during the afternoon. Breed significantly influenced (p<0.001) physiological and physical characteristics of skin, hair, biometric measurements and Iberia and Benezra heat tolerance indices. Santa Ines animals were bigger and had longer, greater number and darker hair, thicker skin, greater respiratory rate and Benezra index and lower Iberia index compared with Morada Nova breed.

Conclusion

Although both breeds can be considered adapted to the environmental conditions of the region, Morada Nova breed is most suitable for farming in the Midwest region. The positive correlation found between the thermographic temperatures and physiological parameters indicates that this technique can be used to evaluate thermal comfort. Also, it has the advantage that animals do not have to be handled, which favors animal welfare.

Keywords: Adaptability, Ewe, Infrared Thermography, Physiology, Thermal Stress

INTRODUCTION

The main environmental factors that affect livestock production are environmental temperature, humidity, solar radiation and wind speed [1]. The climate of a particular region, especially air temperature and relative humidity, directly influences the animal’s production potential. Tropical regions, characterized by high levels of solar radiation and temperature, heat stress is a major factor limiting the development and production of animals [2,3].

The animal’s response to heat stress can be measured by variation in body temperature, respiratory and heart rate (HR), which tend to increase under thermal stress. This results in changes in hematological parameters as heat stress increases water and ion losses [4] as well as increasing plasma and extracellular volume [5]. With a lack of thermal comfort, the animal seeks for ways to lose heat. This involves a series of adaptations of the respiratory, circulatory, excretory, endocrine and nervous systems of animals reared in warm regions [2]. Coordination of all of these systems to maintain the productive potential varies between species, breeds and individuals within the same breed [6]. Therefore, information is necessary regarding heat tolerance and adaptability to indicate breeds for a specific region.

Several indices using different variables have been developed to evaluate thermal stress [7]. The most common empirical model of heat load is the temperature-humidity index (THI), which is a combination of temperature effects and humidity on a single value associated with the level of heat load [8,7] and has been used to assess stress for many years [9]. Besides the environmental index, indices based on measures in animals, which take into account physiological parameters, are also used to determine adaptability. One of the earliest index developed to evaluate thermal stress in animals was the Iberian heat tolerance test (HTC), which uses the rectal temperature (RT) as a variable. Later, a heat tolerance coefficient based on RT and respiratory rate (RR) was developed by Benezra [8].

Most of the methods that are currently used to assess stress or pain in animals are invasive [10]. Thermographic imaging is a noninvasive tool that can be used for this end. These images can be taken at a distance without direct contact with the animal, avoiding temperature increase associated with stress caused by capture, containment and confinement [11], as well as the stress related to handling and physical contact needed to measure RT, heart and RRs as well as blood collection.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate heat tolerance using heat tolerance indices, physiological, physical, thermographic and hematological parameters in Santa Ines (SI) and Morada Nova (MN) sheep breeds in the Federal District, Brazil.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The work was conducted on the Sucupira Farm (Embrapa-Cenargen) located southwest of the city of Brasilia-DF (15°47′S and 47°56′W), with altitudes ranging 1,050–1,250 m, and a total area of 1,763 ha. The climate is Aw, according to Koppen classification system, characterized by two distinct seasons, with rainy summers and dry winters.

Environmental characterization

The environment was characterized using the following measurements: Black globe temperature in the sun and the shade, dry bulb temperature (TDB), and relative humidity (RH) using a hygrometer, every 30 minutes. The wet bulb temperature, and dew point were obtained using the Grapsi digital psychrometric chart [12]. Based on these data, the THI was calculated using the following equation according to [13]:

Where: TDB, dry bulb temperature (°C); RH, relative humidity (%).

Animal characterization

Animal care procedures throughout the study followed protocols approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Use (CEUA) at the University of Brasilia, number 44568/2009.

Twenty-six adult hair sheep, one and a half years old, from two genetic groups (SI: 12 males and 4 females; MN: 7 males and 3 females) were used and data were collected during three consecutive days, twice a day (morning and afternoon), with a total of six repetitions.

Physiological parameters such as RR, HR, and RT and thermographic images were collected in both the morning (4 AM) and afternoon (2 PM). The images of eye, nose, foot and left side of the animal were obtained using an infrared thermograph ThermaCAM (FLIR Systems Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA) using anemittance coefficient of 0.95 with a distance of one meter to measure the temperature of surface of the animal. This camera has infrared resolution 320×240 pixels, with thermal sensitivity of <0.05°C at 30°C (86°F)/50 mK. QuickReport (FLIR Systems Inc., USA) software was used for analysis of the images. The “area” tool was used to obtain the eye, nose, foot (interdigital space at the back of the foot), neck, axilla, groin, rib, shoulder, and rump temperatures of the animals.

Blood was collected by venipuncture using vacutainer tubes with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid when the physiological traits were measured in the morning and afternoon. The numbers of erythrocytes (red blood cell, RBC), leukocytes (WBC), platelets (PLAT) and the concentration of hemoglobin (HB) were determined in an automatic cell counter (MICROS HORIBA, Montpellier, France). The hematimetric parameters (mean corpuscular volume, MCV; mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCH; and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, MCHC) were determined by calculation. Packed cell volume (PCV in %) was determined using capillary tubes in microhematocrit centrifuge. The concentration of total plasma proteins (TPP in g/100 mL) was determined using a refractometer and the plasma retained in a capillary tube. The microhematocrit technique was used for the determination of plasma fibrinogen (FIBR).

The following measurements were taken on each animal: skin thickness (ST) using an adipometer; coat samples (1 cm2) were collected, number of hairs counted and the length of ten longest hairs measured. Skin (shaved shoulder area) and coat colour was measured at the shoulder of the animal using BYK-Gardner Color-guide (Geretsried, Germany) based on the CIELAB system. CIELAB (CIE L*a*b* colour space specified by the International Commission on Illumination) provides a three-dimensional colour space where the a* and b* axes form one plane to which the L* axis is orthogonal. CIELAB represents colour stimuli as an achromatic signal (L*) and two chromatic channels representing yellow-blue (b*) and red-green (a*) [14]. Size measurements on the animals included: shoulder height (SH), thoracic perimeter (TP), back lengths (BKL), and body lengths (BL), rump height (RuH), rump width (RW), and breast width (BW).

HTC based on animal measures were calculated using the following equations:

i) Iberia or Rhoad test [8]: the higher the HTC value the more heat tolerant the animal was considered to be.

Where: HTC = heat tolerance test; 100 = maximum efficiency to maintain body temperature at 39.1°C [15]; 18 = constant; RT = average rectal temperature (°C) based on readings at 4:00 AM and 2:00 PM; 39.1°C = average RT considered normal for sheep [15].

ii) Benezra test [8]: the lower the value the more heat tolerant the animal was considered to be:

Where: HT = heat tolerance index; RT = rectal temperature in °C; RR = respiratory rate in breaths per minute; 39.1 = normal RT of sheep (°C); and 27 = normal respiration rate of sheep (breaths/minute) [15].

Another way to evaluate if animals are in thermal stress is to measure respiratory rate and qualifying the severity of heat stress according to panting rate: low: 40–60 breaths per min, medium high: 61 to 80, high: 81 to 120, and severe heat stress: above 200 breaths per min in sheep [16].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.3 (Statistical Analysis Institute, Cary, NC, USA) evaluating the effect of the period of the day, breed and sex on heat tolerance indices, physiological, physical thermographic and hematological parameters. The procedures used included analysis of variance (GLM) to evaluate the difference between breeds and sex, correlation (CORR) and principal component (PRINCOMP) analysis to attempt to understand the sources of variation in the data. Means were compared using adjust Tukey test with a significance level of 5% (p<0.05).

RESULTS

High daily air temperature variation was seen during the experiment with maximum temperature of 43.2°C in the afternoon and minimum of 14.6°C in the morning. The relative humidity also varied during the day, with low relative humidity in the afternoon (Table 1). High THI was observed in the afternoon (mean 79; maximum 89), reaching values classified as danger and emergency [17], while in the morning the animals were in thermal comfort with mean and maximum THI of 59 and 61, respectively. Based on the scale proposed by Silanikove (2000), which qualifies the severity of heat stress according to breath rate, 37% of the animals in this experiment were under heat stress during the afternoon, of which 6.4% were suffered high thermal stress. And in the morning 16% were under stress, of which 5.1% were under high heat stress (Table 2).

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation (SD) and minimum and maximum of climate measures during the experimental period

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning | ||||

| BGTsun | 16.28 | 0.45 | 15.5 | 17.5 |

| BGTsh | 16.76 | 0.52 | 15.5 | 18.5 |

| RH | 90.65 | 6.45 | 75 | 100 |

| TDB | 15.40 | 0.47 | 14.6 | 16.6 |

| TWB | 14.43 | 0.65 | 12.5 | 15.6 |

| Td | 13.86 | 1.02 | 10.83 | 15.2 |

| THI | 59.61 | 0.77 | 58.27 | 61.66 |

| Afternoon | ||||

| BGTsun | 35.65 | 9.70 | 18.5 | 49.5 |

| BGTsh | 28.18 | 3.25 | 22.5 | 34 |

| RH | 39.73 | 18.18 | 13 | 76 |

| TDB | 32.59 | 6.47 | 22.8 | 43.2 |

| TWB | 20.63 | 2.01 | 17.4 | 27.8 |

| Td | 15.23 | 3.84 | 4.62 | 23.86 |

| THI | 78.64 | 4.99 | 70.35 | 89.94 |

BGTsun, black globe temperature in the sun (°C); BGTsh, black globe temperature in the shadow (°C); RH, relative humidity (%); TDB, dry bulb temperature (°C); TWB, wet bulb temperature (°C); Td, dew point (°C); THI, temperature and humidity index.

Table 2.

Respiratory rate (RR) classification of the sheep according to the period of the day

| RR scale1) | Stress level | Morning % animals | Afternoon % animals |

|---|---|---|---|

| <40 breaths/min | No stress | 83.4 | 73.0 |

| 40 to 60 breaths/min | Low | 11.5 | 16.6 |

| 61 to 80 breaths/min | Medium-high | - | 4.0 |

| 81 to 120 breaths/min | High | 5.1 | 6.4 |

| Above 200 breaths/min | Severe | - | - |

Scale adapted from Silanikove (2000).

RT, RR, PCV, TPP, RBC, HB, PLAT, FIBR, MCV, MCHC, MCH, thermographic temperatures and Benezra index were influenced by the period of the day (Tables 3 and 4). The RT, RR, thermographic temperatures and the Benezra index were higher during the afternoon and most of the blood parameters were lower in this period. The period of the day did not influence the HR, however these values were high both in the morning and afternoon, with means above reference values for this species [15].

Table 3.

Means for physiological and blood traits in Santa Ines and Morada Nova sheep breeds during three days of experiment1)

| Items | RT | HR | RR | PCV | TPP | WBC | RBC | HB | PLAT | FIBR | MCV | MCHC | MCH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | |||||||||||||

| Morning | 37.9a | 98.5a | 25.9a | 29.2a | 6.7a | 7.9a | 8.8a | 9.6a | 7.89b | 410.9a | 33.3a | 32.9a | 10.9a |

| Afternoon | 39.1b | 103.6a | 44.0b | 27.9b | 6.6b | 7.7a | 8.3b | 8.9b | 8.94a | 329.7b | 33.8b | 31.5b | 10.6b |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male | 38.8a | 98.7a | 34.7a | 29.9a | 6.7a | 7.3b | 8.7a | 9.6a | 9.31a | 377.4a | 34.4a | 32.3a | 11.0a |

| Female | 38.3b | 102.8a | 35.1a | 27.7b | 6.6a | 8.2a | 8.4b | 8.9b | 7.77b | 364.7a | 32.9b | 32.1a | 10.6b |

| Breed | |||||||||||||

| Santa Ines | 38.5a | 100.6a | 39.1a | 27.6b | 6.8a | 8.3a | 8.4b | 8.9b | 7.57b | 366.7a | 33.0a | 32.6a | 10.71a |

| Morada Nova | 38.5a | 101.7a | 28.3b | 30.3a | 6,4b | 7.1b | 8.8a | 9.6a | 9.77a | 375.4a | 34.4b | 31.8b | 11b |

| Reference values* | 38.3–39.9 | 70–90 | 20–34 | 27–45 | 6–7,5 | 04–12 | 09–15 | 09–15 | 2,5–7,5 | 100–500 | 28–40 | 31–34 | 08–12 |

RT, rectal temperature (°C); HR, heart rate (beats/min); RR, respiratory rate (movements/min); PCV, packed cell volume (%); TPP, total plasma protein (g/dL); FIBR, plasma fibrinogen (mg/dL); WBC, leukocytes; RBC, red blood cell (106/μL); HB, concentration of hemoglobin (g/dL); MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; PLAT, platelets.

Means followed by different letters in the same column are significantly different using the Tukey test (p<0.05).

Table 4.

Means for thermographic temperatures and heat tolerance indices in Santa Ines and Morada Nova sheep breeds during three days of experiment

| Neck | Axilla | Rib | Groin | Rump | Shoulder | Eye | Nose | Foot | Ibéria | Benezra | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Morning | 30.2a | 34.9a | 30.7a | 34.5a | 27.8a | 32.5a | 36.3a | 34.7a | 24.3a | 110.58a | 1.93b |

| Afternoon | 34.7b | 37.5b | 37.6b | 37.6b | 34.0b | 36.8b | 38.4b | 38.4b | 35.2b | 110.58a | 2.63a | |

| Sex | Male | 32.6a | 36.5a | 33.5a | 36.3a | 31.5a | 34.8a | 37.8a | 34.9a | 29.7a | 105.70b | 2.28a |

| Female | 32.2b | 36.5a | 32.8b | 36.0a | 30.5b | 34.5b | 36.9b | 35.1a | 29.4a | 114.16a | 2.28a | |

| Breed | Santa Ines | 32.1a | 36.2a | 32.9a | 36.2a | 30.4a | 34.6a | 37.3a | 35.0a | 29.4a | 110.58b | 2.43a |

| Morada Nova | 32.7b | 36.3a | 33.3b | 35.9a | 31.7b | 34.7a | 37.5a | 35.0a | 29.7a | 110.59a | 2.03b |

Means followed by different letters in the same column are significantly different using the Tukey test (p<0.05).

Coat traits, morphometric measures, RT, PCV, WBC, RBC, HB, PLAT, MCV, MCH, thermograph temperatures and Iberia index were influenced by sex (Tables 3, 4 and 5). The males SI had higher morphometric measures, RT, PCV, MCV, MCHC, MCH. Skin and hair brightness, hair thickness and Iberia index were higher in females. Regarding surface temperatures, these were generally higher in the males.

Table 5.

Breed and sex interaction on physical characteristics during three days of experiment

| SI | MN | |

|---|---|---|

| Skin thickness | ||

| Male | 6.19aA | 5.66B |

| Female | 5.11bB | 5.88A |

| Hair thickness | ||

| Male | 0.11aA | 0.88aB |

| Female | 0.10bB | 0.45bA |

| Number of hair | ||

| Male | 515.5A | 286.8B |

| Female | 497.29A | 312.12B |

| Hair length | ||

| Male | 1.57aA | 1.11aB |

| Female | 1.37bA | 1.05aB |

| L*skin | ||

| Male | 40.29bB | 50.26aA |

| Female | 49.40aB | 54.84bA |

| a* skin | ||

| Male | 1.48aB | 4.10aA |

| Female | 0.74bB | 3.13bA |

| b*skin | ||

| Male | 1.86B | 5.33aA |

| Female | 2.44B | 6.62bA |

| L* hair | ||

| Male | 18.713Bb | 36.305A |

| Female | 24.257aB | 35.682A |

| a* hair | ||

| Male | 5.14bB | 11.16aA |

| Female | 6.491aA | 7.11bA |

| b* hair | ||

| Male | 5.14bB | 20.59A |

| female | 6.49aB | 21.83A |

| Body length | ||

| Male | 69.37aA | 58.44B |

| Female | 61.04bA | 58.82B |

| Back length | ||

| Male | 58.62aA | 46.89B |

| Female | 48.28bA | 46.82A |

| Shoulder height | ||

| Male | 69.57aA | 66.15aB |

| Female | 65.51bA | 64.46bA |

| Thoracic perimeter | ||

| Male | 78.25aA | 70.05B |

| Female | 70.80bA | 71.70A |

| Rump height | ||

| Male | 72.07A | 68.27aB |

| Female | 67.11bA | 66.41bA |

| Breast width | ||

| Male | 15.6aA | 13.39B |

| Female | 13.05bA | 12.85A |

| Rump width | ||

| Male | 14.1aA | 10.56aB |

| Female | 12.20bA | 11.03bB |

L*, brightness; and chromatic channels representing b*, yellow-blue; a*, red-green (CIELAB); SI, Santa Ines; MN, Morada Nova.

Means followed by different capital letters in the same line and different lower case letters in the same column are significantly different using the Tukey test (p<0.05).

Morphometric measures, coat traits, RR, PCV, TPP, WBC, RBC, HB, PLAT, MCV, MCHC, MCH, some thermographic temperatures and Iberia and Benezra indices were influenced by breed (Tables 3, 4 and 5). SI animals were bigger and had longer, greater number and darker hair, thicker skin, greater RR, higher TPP, HB, MCHC, WBC, Benezra index and lower Iberia index compared with MN breed.

The correlation between physiological parameters, size mea surements, heat tolerance index and coat traits were low (Table 6). RT was negatively correlated with skin brightness (L*) and positively with BL, BKL, TP, RuH, ST. Regarding heat tolerance indices, size measurements, skin, and hair brightness were negatively correlated with Benezra index and a positive correlation was observed between Iberia index and hair and skin brightness. Surface temperatures were positively correlated with RT, RR, and Benezra index, with highest correlations with RT (Table 7). Regarding blood parameters, a direct relationship was noted between HR, number of RBC and HB concentration and there was a negative correlation between these blood parameters and Iberia index and THI (Table 8).

Table 6.

Correlations between physical characteristics, physiological parameters and heat tolerance indices1)

| RT | RR | HR | Iberia | Benezra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | 0.19 | 0.08 | −0.10 | −0.42 | 0.15 |

| BKL | 0.22 | 0.09 | −0.13 | −0.49 | 0.15 |

| SH | 0.13 | 0.06 | −0.18 | −0.30 | 0.01 |

| TP | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.04 | −0.54 | 0.18 |

| RuH | 0.21 | 0.15 | −0.13 | −0.48 | 0.04 |

| BW | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.00 | −0.39 | 0.14 |

| RW | 0.11 | 0.24 | −0.09 | −0.22 | 0.25 |

| ST | 0.20 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.44 | 0.08 |

| HT | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.08 |

| NH | 0.00 | 0.10 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| HL | 0.14 | 0.27 | −0.02 | −0.28 | 0.29 |

| L*skin | −0.23 | −0.15 | 0.01 | 0.52 | −0.16 |

| a*skin | 0.12 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.29 | −0.12 |

| b*skin | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.13 |

| L*hair | −0.07 | −0.17 | 0.07 | 0.17 | −0.17 |

| a*hair | −0.02 | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.16 |

| b*hair | −0.06 | −0.17 | 0.11 | 0.12 | −0.19 |

RT, rectal temperature (°C); HR, heart rate (beats/min); RR, respiratory rate (movements/min); SH, shoulder height; TP, thoracic perimeter; BKL, back length; BL, body length; RuH, rump height; RW, rump width; BW, breast width; ST, skin thickness; HT, hair thickness; NH, number of hairs; HL, length of hair; L*, brightness; chromatic channels representing b*, yellow-blue; a*, red-green (CIELAB).

Numbers in bold are statistically significant level.

Table 7.

Correlations between thermographic temperatures, physiological parameters, heat tolerance indices and physical characteristics1)

| Neck | Axilla | Groin | Rump | Rib | Shoulder | Eye | Nose | Foot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.72 |

| RR | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.53 |

| HR | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.23 |

| IBERIA | −0.03 | −0.23 | −0.17 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.17 | −0.04 | 0.02 |

| BENEZRA | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.52 |

| ST | −0.01 | 0.10 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.10 | 0.05 |

| HT | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.22 | −0.02 | −0.05 |

| NH | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.03 |

| HL | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.25 | −0.18 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| L*skin | 0.01 | −0.12 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.14 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| a*skin | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.06 |

| a*skin | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.14 | 0.09 |

| L*hair | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.12 | 0.03 |

| a*hair | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.12 | −0.08 | 0.03 |

| b*hair | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 0.03 |

RT, rectal temperature (°C); HR, heart rate (beats/min); RR, respiratory rate (movements/min); ST, skin thickness; HT, hair thickness; NH, number of hairs; HL, length of hair; L*, brightness; chromatic channels representing b*, yellow-blue; a*, red-green (CIELAB).

Numbers in bold are statistically significant level.

Table 8.

Correlations between blood and physiological parameters and heat tolerance indices1)

| PCV | TPP | FIBR | WBC | RBC | HB | MCV | MCH | MCHC | PLAT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.27 | 0.14 | −0.06 | −0.11 | 0.01 | −0.10 | −0.10 | 0.16 |

| RR | −0.16 | −0.05 | −0.24 | 0.14 | −0.07 | −0.15 | −0.11 | −0.15 | −0.01 | −0.05 |

| HR | 0.17 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.20 | −0.20 | −0.17 | 0.08 | −0.05 |

| THI | −0.16 | −0.12 | −0.30 | 0.03 | −0.19 | −0.31 | 0.08 | −0.19 | −0.25 | 0.27 |

| IBERIA | −0.41 | −0.19 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.34 | −0.40 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.06 |

| BENEZRA | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.16 | 0.12 | 0.07 | −0.03 | −0.12 | −0.19 | −0.03 | −0.02 |

RT, rectal temperature (°C); HR, heart rate (beats/min); RR, respiratory rate (movements/min); PCV, packed cell volume (%); TPP, total plasma protein(g/dL); FIBR, plasma fibrinogen (mg/dL); WBC, leukocytes; RBC, red blood cell (106/μL); HB, concentration of hemoglobin (g/dL); MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; PLAT, platelets.

Numbers in bold are statistically significant level.

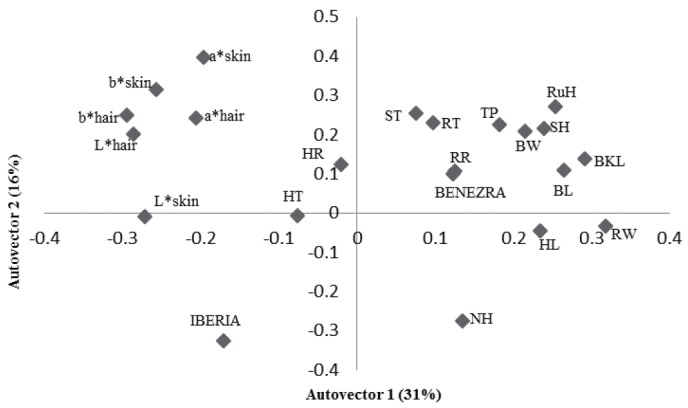

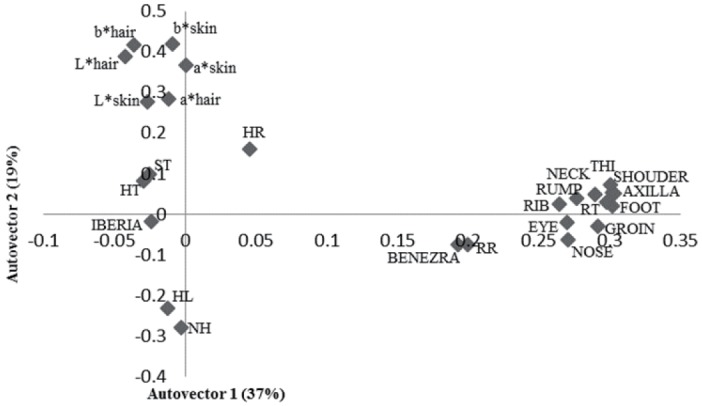

The principal component analysis showed that 47% of the variation was explained by physiological and physical variables of the animals (Figure 1). The physical components such as SH, TP, back and BL, RuH, RW, and RW were grouped. The RT was directly related with these morphometric measures and ST. High RT, larger animals and thicker skin were related with higher Benezra and lower Iberia index. The higher the hair brightness lowers RT, respiratory rate and Benezra index. Regarding surface temperatures, 56% of the variation was explained by the characteristics studied (Figure 2). It was noted a direct relation between these temperatures, physiological components, THI and Benezra index and indirect with Iberia index.

Figure 1.

First two autovectors for heat tolerance indices and physiological and physical traits in sheep in the Federal District, Brazil. RT, rectal temperature (°C); HR, heart rate (beats/min); RR, respiratory rate (movements/min); SH, shoulder height; TP, thoracic perimeter; BKL, back length; BL, body length; RuH, rump height; RW, rump width; BW, breast width; ST, skin thickness; HT, hair thickness; NH, number of hairs; HL, length of hair; L*, brightness; chromatic channels representing b*, yellow-blue; a*, red-green (CIELAB).

Figure 2.

First two autovectors for heat tolerance indices, thermograph temperatures and physiological and physical traits in sheep in the Federal District, Brazil. RT, rectal temperature (°C); HR, heart rate (beats/min); RR, respiratory rate (movements/minute); ST, skin thickness; HT, hair thickness; NH, number of hairs; HL, length of hair; L*, brightness; chromatic channels representing b*, yellow-blue; a*, red-green (CIELAB).

DISCUSSION

Environmental parameters

The ability to maintain body temperature can be compromised when environmental conditions limit metabolic heat dissipation or contribute to the thermal load of the animal [18]. In this study, high THI was observed in the afternoon, reaching values classified as danger and emergency [17]. This high amplitude of thermal variation observed in the present study have already been reported in the Midwest region of Brazil, where animals tend to suffer from cold stress at night and heat stress during the day [19]. The animal’s ability to respond to heat stress depends upon exposure to low temperatures during the night, and more specifically, the duration and intensity of this low temperature [9]. Thus, low temperatures recorded during the night may have aided in the recovery of thermal stress suffered during the day.

Physical characteristics

The males and SI animals are larger than females and MN, respectively. A study in the midwest of Brazil, comparing three genetic groups of lambs, noted that larger animals had higher RR and RT [20]. The same was observed in this study, SI had greater RR and the males higher RT. Larger animals have more difficulty to dissipate heat to the environment because of the lower proportion of surface contact available for heat loss [21].

Coat brightness and RT were inversely correlated, because lighter skin and hair colors reflect solar radiation, decreasing heat retention. The SI sheep used in this study had darker coat than MN, which possibly indicates better adaptation of MN due to less heat absorption. This can be noted in some physiological components such as RR, which was lower in MN, and heat tolerance indices that indicated better adaptation of this breed. Studies with West African Dwarf sheep in Nigeria also observed that sheep with dark pigmentation were more prone to heat stress than those with light pigmentation, suggesting that selection should target animals with light coat color in order to improve animal welfare and production efficiency [22].

The better adaptability of MN can also be observed in relation to ST and hair characteristics. It was noted that the MN had thinner skin, shorter and fewer number of hair than SI. Previous studies had suggested that less amount of hair facilitates air penetration, favoring heat transfer [23]. In the present study, in the principal component analysis, a direct relationship between these physical components (ST and number and length of hair) and RR and RT was observed. Thicker hair coat have also been associated to higher skin temperature and RR in sheep [24].

Physiological parameters

Respiratory rate is the first thermoregulation mechanism used by the animal to maintain its body temperature. In this study, RR was affected by breed and period of the day. The increase in RR in the afternoon as a result of higher environmental temperature was also observed in several studies [25]. MN had lower respiratory rate than SI, indicating better adaptation.

In this study, RT was affected by period of the day, being lower in the morning, indicating that the conditions in this period were less stressful. The mean RTs were within reference values for sheep, being slightly higher in SI when comparing to MN. Sheep RT can rises above the normal range when ambient temperature reaches 32°C [26], however in the present work it was observed that even when subjected to high environmental temperatures (above 40°C) the RT remained within reference values, indicating good adaptation. Animals adapted to hot climates have morphological and physiological adaptations that assist heat dissipation [25].

Blood parameters

All blood parameters were within the reference values [27] and with higher values in the morning, except the number of PLAT which had a higher average in the afternoon. A heat tolerance study in sheep, also observed a reduction of some blood components in the afternoon such as HB concentration and MCH [20]. The heat may cause a reduction of blood constituents due to hemodilution effect where more water is transported by the circulatory system to help in evaporative cooling. Also, the greater blood flow can increase cellular circulation [28]. In the present study, this can be corroborated with the reduction of TPP during the afternoon which could indicate hemodilution.

A negative correlation between air temperature, PCV, number of RBCs and HB concentration was reported [20], while in the present study a negative relationship was also noted between these hematological constituents and THI, which can be attributed to the hemodilution effect [28]. With regard to heat tolerance indices, the inverse relationship between Iberia index and number of RBCs and HB concentration indicates that these blood constituents can be lower in the more adapted animal.

There was no effect of period of the day on the number of leukocytes. However, a higher number of leukocytes have been reported in the afternoon [2,20]. Also, the number of leukocytes was within reference values, which may be indicative of heat tolerance even in thermal stress situation [20]. Nevertheless, leukocytosis has been associated to heat stress in sheep [2], this difference may be attributed to the age of the animals used in the studies. With regard to breed, considering that the number of leukocytes is influenced by stress hormones released by the adrenal cortex [27], the higher number of white blood cells in SI observed in the present study may be due to an increase in the release of hormones such as cortisone and adrenaline [20].

Heat tolerance index

Among the heat tolerance indices, the Benezra index is the only one which considers RR as a variable. The direct relationship between this index and physiological parameters such as RR and RT, indicates that animals with a lower RR and RT are considered more adapted. The Benezra index was lower for MN, indicating better adaptability. MN sheep was also considered more adapted than SI according to Iberia index, which was higher for MN. The inverse relationship between the Iberia index and physiological parameters indicated that more adapted animals had lower RT. Perhaps breeding SI with other breeds, such as Sufolk, in order to obtain bigger animals may be responsible for this poorer adaptability of SI in comparison to MN, because heavier animals has less surface area for heat loss [21].

Thermographic temperatures

Infrared thermography has been shown to be related to several physiological processes associated with heat tolerance [19,29]. In the present study, the thermographic temperatures of the several body areas measured using an infrared camera were affected by period of the day and, as expected, were lower in the morning period with cooler environmental temperatures. A relationship between time of day and foot temperature have also been reported in Comisana sheep kept under a natural photoperiod [30]. Body temperature variation that increased throughout the day and decreased at night had also been reported by several researchers [19]. This variation was probably due to the lower thermal balance between the surface of the animal and the air temperature in the afternoon. As heat dissipation mechanisms (radiation, convection, and conduction) are dependent on this thermal balance, when the air temperature rises, the thermal gradient between the surface and the environment decreases.

In principal component analysis, body temperatures behaved similarly. In a thermographic evaluation of climatic conditions on lambs, the temperature of the nose was the only one that behaved differently [19]. However, here this thermographic temperature was grouped with the others. Regarding difference between breeds, SI lambs have been associated to higher skin temperatures due to a darker coat which favors heat absorption resulting in higher surface temperature [19], but in the present study in some body regions such as the neck, ribs and rump, SI animals had lower surface temperature.

The positive correlations between these thermographic temperatures, the Benezra index and physiological parameters, especially RT, indicate that this technique can be used to evaluate thermal comfort and has the advantage that animals do not have to be handled. Regarding all the body areas analyzed, the axilla was the one that best correlated with RT, so it can be considered a good area to measure body temperature using an infrared thermography.

CONCLUSION

The environmental index indicated that sheep suffered heat stress during the afternoon, but due to the good adaptation of MN and SI breeds, these animals were able to maintain their physiological and blood parameters within reference values. Although both breeds can be considered adapted to the environmental conditions, MN breed may be considered more adapted for farming in the Midwest region because of its physical characteristics which favors heat tolerance. The use of infrared thermography to evaluate thermal comfort is a good alternative, having the advantage that animals do not have to be handled, which favors animal welfare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank CAPES, CNPq and Dr. Alexandre Floriani Ramos (Embrapa-Cenargen).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hulme PE. Adapting to climate change: Is there scope for ecological management in the face of a global threat? J Appl Ecol. 2005;42:784–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McManus C, Paludo G, Louvandini H, et al. Heat tolerance in brazilian sheep: Physiological and blood parameters. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2009;41:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s11250-008-9162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McManus C, Hermuche P, Paiva SR, et al. Geographical distribution of sheep breeds in brazil and their relationship with climatic and environmental factors as risk classification for conservation. Braz J Sci Tech. 2014;1:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beede D, Collier R. Potencial nutricional strategies for managed cattle during thermal stress. J Anim Sci. 1986;62:543–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McManus C, Louvandini H, Paim T, et al. The challenge of sheep farming in the tropics: Aspects related to heat tolerance. Braz J Anim Sci. 2011;40:107–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marai I, Haeeb A. Buffalo’s biological functions as affected by heat stress—a review. Livest Sci. 2010;127:89–109. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohmanova J, Misztal I, Cole J. Temperature-humidity índices as indicators of milk production losses due to heat stress. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90:1947–56. doi: 10.3168/jds.2006-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaughan J, Mader T, Gebremedhin K. Rethinking heat index tools for livestock. In: Collier RJ, Collier JL, editors. Environmental physiology of livestock. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 243–65. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaughan JB, Mader TL, Holt SM, Lisle A. A new heat load index for feedlot cattle. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:226–34. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart M, Stafford K, Dowling S, Schaefer A, Webster J. Eye temperature and heart rate variability of calves disbudded with or without local anaesthetic. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:789–97. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart M, Webster J, Schaefer A, Cook N, Scott S. Infrared thermography as a non-invasive tool to study animal welfare. Anim Welf. 2005;14:319–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melo E, Lopes DDC, Corrêa P. Grapsi-programa computacional para o cálculo das propriedades psicrométricas do ar. Eng Agric. 2004;12:154–62. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mader TL, Davis M, Brown-Brandl T. Environmental factors influencing heat stress in feedlot cattle. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:712–9. doi: 10.2527/2006.843712x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westland S. Review of the cie system of colorimetry and its use in dentistry. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2003;15:S5–S12. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2003.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reece WO, Erickson HH, Goff JP, Uemura EE. Dukes’ physiology of domestic animals. 13th ed. New Jersey, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silanikove N. Effects of heat stress on the welfare of extensively managed domestic ruminants. Livest Prod Sci. 2000;67:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn GL, Gaughan JB, Mader TL, Eigenberg RA. Thermal indices and their applications for livestock environments. In: Hillman PE, DeShazer JA, editors. Livestock energetics and thermal environmental management. St. Joseph, MI: Am Soc Agric Biol Eng; 2009. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dikmen S, Hansen P. Is the temperature-humidity index the best indicator of heat stress in lactating dairy cows in a subtropical environment? J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:109–16. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paim TDP, Borges BO, Lima PDMT, et al. Thermographic evaluation of climatic conditions on lambs from different genetic groups. Int J Biometeorol. 2013;57:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s00484-012-0533-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correa MPC, Cardoso MT, Castanheira M, et al. Heat tolerance in three genetic groups of lambs in central Brazil. Small Rumin Res. 2012;104:70–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McManus C, Castanheira M, Paiva SR, et al. Use of multivariate analyses for determining heat tolerance in brazilian cattle. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2011;43:623–30. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fadare AO, Peters SO, Yakubu A, et al. Physiological and haematological indices suggest superior heat tolerance of white-coloured west african dwarf sheep in the hot humid tropics. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;45:157–65. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebremedhin K, Ni H, Hillman P. Modeling temperature profile and heat flux through irradiated fur layer. Trans ASAE. 1997;40:1441–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McManus C, Louvandini H, Gugel R, et al. Skin and coat traits in sheep in brazil and their relation with heat tolerance. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2011;43:121–6. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9663-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marai I, El-Darawany A, Fadiel A, Abdel-Hafez M. Physiological traits as affected by heat stress in sheep—a review. Small Rumin Res. 2007;71:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson BE, Jónasson H. Temperature regulation and environmental physiology. In: Duke HH, Swenson MJ, Reece WO, editors. Dukes’ physiology of domestic animals. 11th ed. Ithaca, NY: Comstock; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain NC. Essentials of veterinary hematology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ei-Nouty F, Ai-Haidary A. Seasonal variations in hematological values of high-and average-yielding holstein cattle in semi-arid environment. J King Saud Univ. 1990;2:173–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McManus C, Bianchini E, Paim TP, et al. Infrared thermography to evaluate heat tolerance in different genetic groups of lambs. Sensors. 2015;15:17258–73. doi: 10.3390/s150717258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Alterio G, Casella S, Gatto M, et al. Circadian rhythm of foot temperature assessed using infrared thermography in sheep. Czech J Anim Sci. 2011;56:293–300. [Google Scholar]