Abstract

The aim was to investigate thermal response, hydration behaviour and performance in flatwater kayaking races in tropical conditions (35.9 ± 2.8°C and 64 ± 4% RH). Eight regionally ranked paddlers (ARP) participated in the 2012 Surfski Ocean Racing World Cup in Guadeloupe (an inline 15-km downwind race). Core temperature (Tc) and heart rate (HR) were measured using portable telemetry units, while water intake was deduced from backpack absorption. The kayakers were asked to rate both their comfort sensation and thermal sensation on a scale before and after the race. The performance was not related to any measured parameters, and high values of post-race Tc were related to high pre-race Tc. The present study demonstrated that average-range paddlers are able to perform in a tropical climate, drinking little and paddling at high intensity without any interference from thermal sensations. Core temperature at the end of the race was positively related to pre-race Tc, which reinforces the importance of beginning surfski races with a low Tc and raises the question of pre-cooling strategies for paddlers, and more specifically for those with a low convection body surface.

Keywords: hot-wet climate, long distance activity, self-hydration, ecologic conditions

INTRODUCTION

It is well known that aerobic cyclic exercise is negatively affected by a hot environment [1, 2], particularly in a hot and humid environment (i.e., a so-called tropical climate) due to limited evaporative processes [3–6]. Although considerable information has been gathered on the physiological adaptation to hot/dry climates, very little is known about “how to exercise in a tropical climate” where more than 33% of the world population lives [3].

Surfski paddling is a cyclic physical activity that has been gaining popularity throughout the world. Although surfski paddling is particularly challenging during long-distance events in hot conditions, very few studies have investigated this sport in normal range participants: Sun et al. [7] demonstrated that nationally ranked kayakers became dehydrated during a one-hour marathon-pace event conducted in a tropicalized laboratory, while Noakes et al. [8] demonstrated that a four-stage, 244-km surfski marathon was associated with a low level of dehydration in internationally ranked ones.

Recently [9] we demonstrated that internationally ranked paddlers (IRP) performing a long-distance world-class event (i.e., more than 2 hours) in a tropical climate were able to increase their Tc and drink little water without any interference from thermal sensations, the better paddlers increasing more their Tc and drinking less. This phenomenon, well known in high-level runners (e.g., Olympic athletes [10]), needs to be confirmed in basically to well-trained paddlers to give some guidelines to ensure safe and efficient surfski paddling in tropical conditions.

The aim of the present study was thus to investigate the hydration behaviour and thermoregulatory processes during international outdoor surfski competitions performed with regionally ranked athletes in tropical conditions and their possible relation to performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Eight regionally ranked subjects (average-range paddlers (ARP); age: 29.7 ± 4.3 years; body mass: 80.3 ± 11.7 kg; height: 181.4 ± 6.8 cm) participated in the 2012 Surfski Ocean Racing World Cup in Guadeloupe (an inline 15-km downwind race) (mean 35.9 ± 2.8°C and 64 ± 4% RH). All gave informed written consent, and the protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Guadeloupe University and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The session was performed in the early morning (starting at 8 am) and the performance was reported through the official results given after the Surfski Ocean Racing World Cup. Core temperature (Tc) was measured before and after the race with a CorTemp 2000 ambulatory remote sensing system (HQ Inc., Palmetto, FL, USA), using pills that were given at least 3 hours before the race. Heart rate (HR) was monitored continuously with a portable telemetry unit (Polar RS800SD, Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland) recording data every 5 seconds. Body mass was assessed (±0.1 kg) before and after the race (Planax Automatic, Teraillon, Chatoux, France). The change in body mass, corrected for fluid intake and urine loss (none of the subjects reported urine loss during the event), but not accounting for metabolic fuel oxidation, metabolic water gain, or respiratory water losses, was used to estimate sweat loss (Baker et al. 2009). As no aid stations were used in the surfski race, fluid intake (i.e., water at ambient temperature) during the race was estimated as the difference in the 4-L plastic pocket of the backpack water weight. The paddlers were asked to rate both their comfort sensation (CS) and thermal sensation (TS) on a scale [11] before the start and at the end of the race, as previously described [09]. The outside temperature and hygrometry were monitored for the duration of the race on a boat following the paddlers (QUESTemp° 32 Portable Monitor, QUEST Technologies, Oconomowoc, WI, USA).

Statistics

Each variable was tested for normality using the skewness and kurtosis tests, with acceptable Z values not exceeding +1 or -1. Once the assumption of normality was confirmed, parametric tests were performed. The following variables were analysed using unpaired t-tests: Tc, variation in Tc (deltaTc), water intake (WI), difference in body mass (deltaBM), total body water loss (TBWL), and HR in absolute and/or relative values (i.e., h−1). Pairwise correlations were used to analyse the effect of variables on performance, water intake and Tc increase (BM, deltaBM, WI, TBWL, lean body mass: LBM, and body surface/weight ratio). Stepwise multiple linear regressions determined the best predictors of performance, water intake and Tc. Data are displayed as mean ± SD, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

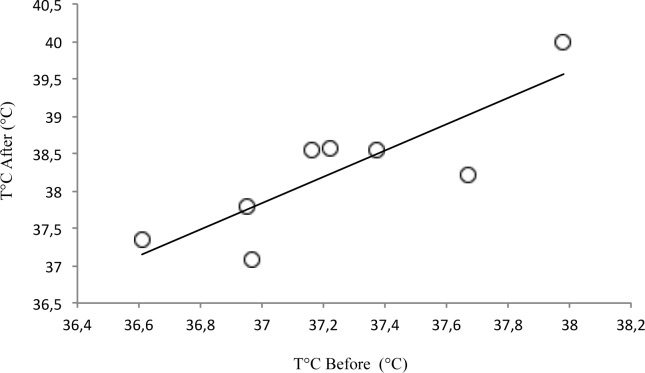

None of the measured parameters analysed was correlated with the performance, or with each other (Table 1), excepted Tc measured after the race, which was significantly correlated with Tc measured before the race (Figure 1, Tc after = 0.50Tc before + 19.73; R2=0.59, p < 0.03).

TABLE 1.

Performance, core temperature (T°C), change in T°C (delta T°C), body mass (BM) and body mass loss (BML), water intake (WI- and total body water loss (TBWL), heart rate (HR), thermal comfort (TC) and sensation (TS) during the 15 km surfski race.

| 15 km surfski race | ||

|---|---|---|

| Performance | s | 5069 ± 626 |

| m · s−1 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | |

| T°C before | °C | 36.7 ± 1.7 |

| T°C after | 38.1 ± 1.1a | |

| delta T°C | °C | 1.4 ± 1.1 |

| °C · h−1 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | |

| Delta BM | kg | - 0.9 ± 0.4 |

| kg · h−1 | -0.6 ± 0.4 | |

| WI | L | 0.8 ± 0.6 |

| L · h−1 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | |

| TBWL | L | -1.7 ± 0.8 |

| L · h−1 | -1.2 ± 0.7 | |

| HR | bpm | 163 ± 12 |

| TC | 2.0 ±1.1 | |

| TS | 3.4 ± 0.7 | |

FIG. 1.

Relationship between body temperature after and before the 15 km race

DISCUSSION

The most important findings of the present study were that (1) performance was not related to any measured parameters, especially pre- or post-race Tc or fluid intake or loss; and (2) high values of post-race Tc were related to high pre-race Tc.

The performance expressed in relative units was not different from the performance noted in our previous study [9], indicating that ARP are paddling at a pace similar to the one used by IRP during a 35-km race. Similar mean HR was also observed between races. If considering that at a similar pace and HR, ARP increased their Tc at a pace of 1°C.h−1 over a 15-km race, whereas IRP increased theirs by only 0.45°C.h−1 over 35 km, these data suggest that, in similar tropical conditions, the ARP have a lower efficiency of the thermoregulation processes than IRP, as noted by Pandolf et al. [12].

Although some participants demonstrated a high peak Tc at the end of exercise (40°C), the average maximal gastrointestinal temperature (mean 38.1°C) was higher than the tympanic temperature noted during a one-hour laboratory kayak event [7] and the rectal temperature noted by Noakes et al. [8], but lower than that recently noted by our group in IRP during a longer duration event [9]. In any case, this level is situated far beyond the rectal temperatures (40.0-42.0°C) reported for heatstroke [13] and lower than the core temperature usually described as being the critical temperature during self-paced exercise [14].

The Tc noted at the end of the race was significantly correlated with the Tc noted before the race, demonstrating that the lower Tc was at the beginning of the event, the lower it was also at the end. However, we did not demonstrate any correlation between the delta Tc and the performance in the present paddlers, whereas we recently demonstrated that the IRP with the greatest increases in Tc were the fastest during a 35-km race [9].

The water intake during the races amounted to very little (around 0.6 L · h−1), especially considering the tropical climate and the sweat loss rate (mean 1.2 L · h−1). However, this intake agrees with the American College of Sports Medicine [15] recommendations for running (as far as we know, there are no recommendations for surfski paddling) to drink 0.4 to 0.8 L · h−1, depending on the runner's anthropometry and the intensity and distance of the event. It is also similar to the data of Noakes et al. [8] of 0.4 to 0.55 L · h−1 during a surfski marathon and those of Sun et al. [7] noted in the laboratory (i.e., 0.5-0.6 L · h−1), and also similar to that noted in our recent study in IRP [9] but greater than the intakes noted during mass-participation road races in similar environments [16, 17]. The fact that in surfski kayaking the paddlers can drink at any time thanks to the water-backpack probably explains the difference in hydration between sports, as recently pointed out by Periard et al. [18].

The estimated sweat loss rate of 1.2 L · h−1 was greater than that reported by Noakes et al. [8], but in the range of previous reports from kayaking and running studies performed in a tropical environment (1.22 L · h−1 for Sun et al. [7]; 1.47 L · h−1 for Byrne et al. [16], 1.45 L · h−1 for Lee et al. [17] and 1.2 L · h−1 for Hue et al. [9]). When this estimated loss was considered together with the water intake, this induced a body mass loss of 2.1% for the race. This is considered to be beyond the normal TBWL fluctuation [19] and has been demonstrated to negatively affect endurance performance [20]. However, a decrease in performance due to dehydration has been shown in subjects already dehydrated before the exercise [20]. In the present study, we did not collect urine or blood samples before races and thus we could not determine whether some of the subjects were dehydrated.

One of the aims of this study was to investigate the effect of a surfski paddle race in a tropical climate on the hydration status of self-hydrating paddlers. If the IRP were recently demonstrated to be able to drink very little without any interference with their performance ability [9], nothing was known about ARP. The subjects of the present study were free to drink as much water as they wanted, with the only limit being the maximum 4 L carried in their backpacks. The mean volume of 0.6 L · h−1 ingested for a sweat loss of 1.2 L · h−1 clearly pointed to voluntary dehydration, as is usually observed in the best runners [21] and in our IRP [9]. It thus seems clear that these subjects, despite great TBWL (0.5-2.7 L) associated with a mean 0-1.5 L of WI inducing a 0.3-1.3 kg loss (mean 0.4-1.8% of body mass loss), did not present severe dehydration or heat illness while drinking ad libitum as described in the literature in high-level marathoners [10], standard runners [17], and recently in IRP [9]. Taken together, these findings reinforce the view that ad libitum hydration is enough for endurance exercise in a hot environment [17, 21, 22, 23]. These results could be surprising if we consider that average-range athletes normally drink at a higher rate than high-level or more trained ones [24, 25]. In a recent study, Hue et al. [9] noted quite pronounced differences between internationally ranked competitors who drank a mean 1.1 L, corresponding to 0.35 L · h−1, and three nationally ranked competitors who drank a mean 2.2 L, corresponding to 0.80 L · h−1.

These results indicate that the subjects of the present study were able to perform surfski paddling in a tropical climate without presenting any signs or symptoms of heatstroke, perhaps because they were acclimated (i.e., living in and training in for at least 2 years) to a hot/dry or tropical climate [3] and also because, as often proclaimed by Noakes et al. [22], humans are adapted to perform in a hot environment.

CONCLUSIONS

To sum up, the present study demonstrated that average-range paddlers are able to perform in a tropical climate, drinking little and paddling at high intensity without any interference from thermal sensations. Core temperature at the end of the race was positively related to pre-race Tc, which reinforces the importance of beginning surfski races with a low Tc and raises the question of pre-cooling strategies for paddlers, and more specifically for those with low a convection body surface. If not for performance increase (we did not observe any significant relation between final performance and lower pre-race temperature), it could be very important for safety reasons.

Further studies are needed to improve knowledge on surfski paddling in the general population in tropical conditions.

Acknowledgements

The present research was partially supported with 2007-2013 PO Antilles-Guyane funding.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maughan RJ. Distance running in hot environments: A thermal challenge to the elite runner. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(Suppl 3):95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nybo L. Cycling in the heat: Performance perspectives and cerebral challenges. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(Suppl 3):71–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hue O. The challenge of performing aerobic exercise in tropical environments: Applied knowledge and perspectives. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011;6:443–454. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.6.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hue O, Galy O. Effect of a silicone swim cap on aerobic performance in tropical conditions: the case of children. J Sports Sci Med. 2012;11:156–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voltaire B, Berthouze-Aranda S, Hue O. Influence of a hot/wet environment on exercise performance in natives to tropical climate. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2003;43:306–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voltaire B, Galy O, Coste O, Recinais S, Callis A, Blonc S, Hertogh C, Hue O. Effect of fourteen days of acclimatization on athletic performance in tropical climate. Can J Appl Physiol. 2002;27:551–562. doi: 10.1139/h02-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun JM, Chia JK, Aziz AR, Tan B. Dehydration rates and rehydration efficacy of water and sports drink during one hour of moderate intensity exercise in well-trained flatwater kayakers. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:261–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noakes TD, Nathan M, Irving RA, van Zyl Smit R, Meissner P, Kotzenberg G, Victor T. Physiological and biochemical measurements during a 4-day surf-ski marathon. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:212–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hue O, Le Jeannic P, Chamari K. A pilot study on How do elite surfski paddlers manage their effort and hydration pattern in the heat. Biol Sport. 2014;31:283–288. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1120936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Rooyen M, Hew-Butler T, Noakes TD. Drinking during marathon in extreme heat: a video analysis study of the top finishers in the 2004 Athens Olympics marathons. S Afr J Sports Med. 2010;3:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker LB, Lang JA, Kenney WL. Change in body mass accurately and reliably predicts change in body water after endurance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105:959–967. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-0982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagge AP, Stolwijk JA, Hardy JD. Comfort and thermal sensations and associated physiological responses at various ambient temperatures. Environ Res. 1967;1:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(67)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandolf KB, Burse RL, Goldman RF. Role of physical fitness in heat acclimatization, decay and reinduction. Ergonomics. 1977;20:399–408. doi: 10.1080/00140137708931642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rae DE, Knobel GJ, Mann T, Swart J, Tucker R, Noakes TD. Heatstroke during endurance exercise: Is there evidence for excessive endothermy? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1193–1204. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816a7155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlader ZJ, Stannard SR, Mûndel T. Exercise and heat stress: performance, fatigue and exhaustion—a hot topic. Brit J Sports Med. 2011;45:3–5. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.063024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ, Stachenfeld NS. American college of sports medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:377–390. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802ca597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne C, Lee JK, Chew SA, Lim CL, Tan EY. Continuous thermoregulatory responses to mass-participation distance running in heat. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:803–810. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218134.74238.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JK, Nio AQ, Lim CL, Teo EY, Byrne C. Thermoregulation, pacing and fluid balance during mass participation distance running in a warm and humid environment. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:887–898. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1405-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Périard JD, Racinais S, Knez WL, Herrera CP, Christian RJ, Girard O. Coping with heat stress during match-play tennis: Does an individualised hydration regimen enhance performance and recovery? Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(Suppl 1):i64–i70. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheuvront SN, Carter R, Sawka MN. Fluid balance and endurance exercise performance. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2:202–208. doi: 10.1249/00149619-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheuvront SN, Carter R, Castellani JW, Sawka MN. Hypohydration impairs endurance exercise performance in temperate but not cold air. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1972–1976. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00329.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Passe D, Horn M, Stofan J, Horswill C, Murray R. Voluntary dehydration in runners despite favorable conditions for fluid intake. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2007;17:284–295. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.17.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hue O, Henri S, Baillot M, Sinnapah S, Uzel AP. Thermoregulation, hydration and performance over 6 days of trail running in the tropics. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35:906–11. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noakes TD. Hydration in the marathon: Using thirst to gauge safe fluid replacement. Sports Med. 2007;37:463–466. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737040-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baillot M, Le Bris S, Hue O. Fluid replacement strategy during a 27-Km trail run in hot and humid conditions. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35:147–152. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]