Although Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty is a commonly performed procedure, it comes at the expense of inevitably lengthier scars and variable outcomes, which has, in part, fueled the debate over long- versus short-scar techniques. Notwithstanding other factors, including age, breast size and ptosis, among others, wound complications persist, and modifications to the Wise pattern reduction have been sought. The authors present a simple versatile technique they believe contribute to improved wound healing and better aesthetic outcomes.

Keywords: Flaps, Lipodermal, Mammoplasty, Reduction

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty is one of the most prevalent procedures providing satisfactory cutaneous reduction, it is at the expense of inevitable lengthier scars and wound complications, especially at the inverted T junction.

OBJECTIVE

To describe a novel technique providing tension-free closure at the T junction through performing triangular lipodermal flaps. The aim is to alleviate skin tension, thus reducing skin necrosis, dehiscence and excessive scarring at the T junction.

METHODS

One hundred seventy-three consecutive procedures were performed on 137 patients between 2009 and 2013. Data collected included demographics, perioperative morbidity and resected breast tissue weight. The follow-up period ranged from three to 30 months; early and late postoperative complications and patient satisfaction were recorded.

RESULTS

Superficial epidermolysis without T-junction dehiscence was experienced in eight (4.6%) procedures while five (2.9%) procedures developed full-thickness wound dehiscence. Ninety-four percent of patients were highly satisfied with the outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

The technique is safe, versatile and easy to execute, providing a tension-free zone and acting as internal dermal sling, thus providing better wound healing with more favourable aesthetic outcome and maintaining breast projection.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE

Même si la réduction mammaire par patron de Wise est l’une des interventions les plus prévalentes pour assurer une réduction cutanée satisfaisante, elle se fait aux dépens de complications plus longues et inévitables des cicatrices et des plaies, particulièrement à la jonction en T inversée.

OBJECTIF

Décrire une technique novatrice sans fermeture de tension à la jonction en T par lambeaux lipodermiques triangulaires. L’objectif consiste à soulager la tension cutanée, réduisant ainsi la nécrose cutanée, la déhiscence et la cicatrisation excessive à la jonction en T.

MÉTHODOLOGIE

Entre 2009 et 2013, 173 interventions consécutives ont été exécutées auprès de 137 patients. Les données colligées incluent la démographie, la morbidité périopératoire et le poids des tissus mammaires réséqués. La période de suivi durait de trois à 30 mois. Les complications postopératoires précoces et tardives et la satisfaction des patients ont été enregistrées.

RÉSULTATS

Huit interventions (4,6 %) se sont associées à une épidermolyse superficielle sans déhiscence de la jonction en T, tandis que cinq (2,9 %) ont donné lieu à une déhiscence pleine épaisseur de la plaie. Ainsi, 94 % des patients étaient pleinement satisfaits des résultats.

CONCLUSIONS

La technique est sécuritaire, polyvalente et facile à exécuter, assure une zone sans tension et agit comme une attelle dermique interne, ce qui entraîne une meilleure cicatrisation de la plaie, aux résultats esthétiques plus favorables, qui maintient la projection mammaire.

Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty (WRM) is a commonly performed procedure for aesthetic and functional purposes, and for symmetrization procedures in patients undergoing breast reconstruction. The technique provides satisfactory cutaneous reduction in both the transverse and vertical aspect, but at the expense of inevitable lengthier scars with possible risks for cutaneous necrosis at the T junction. This has fueled the ongoing debate over long-versus short-scar techniques. The aesthetic outcome could vary with Wise pattern due to the extent of scarring. However, other factors should be considered including age, breast size, degree of ptosis, quality of breast skin, resected volume and comorbidities. Wound problem complications remain relatively common, as well as the tendency of the outcome to deteriorate in some cases, with loss of projection and bottoming out of the lower breast pole (1–4). T-junction wound dehiscence and infections are the most common complications encountered, with evidence of their impact on surgical outcomes rarely reported in the literature. We describe an additional modification using triangular lipodermal flaps in the WRM technique aiming to reduce dehiscence with scar formation at the T-junction and, thus, a more predictable aesthetic outcome.

METHODS

Between 2009 and 2013, 173 consecutive procedures were performed on 137 patients with a mean age of 42 years (range 19 to 73 years) by one of the authors (HK). The inclusion criteria for the reduction mammoplasty included: symptomatic benign breast hypertrophy and gigantomastia (n=36); and contralateral breast symmetrization post-breast reconstruction for breast cancer (n=101). Patients who were current smokers, or who had a body mass index (BMI, Quetelet’s index [weight/height]) >32 kg/m2) and uncontrolled diabetes were excluded. The mean BMI for this cohort was 28.7 kg/m2. Data collected included demographics, breast size(s), degree of ptosis, perioperative morbidity and resected breast tissue weight. The follow-up period ranged from three to 30 months (mean 14 months), in which early and late postoperative complications were recorded. The emphasis on wound healing progress, specifically at the T junction, was recorded and compared with previously reported data. All patients were assessed subjectively and objectively for their outcome satisfaction through a clinical questionnaire and clinical assessment. The structure of the evaluation included the following domains: scar symptoms (pain, itchiness, lumpiness, and discomfort and overall appearance of the breast and its shape); consciousness of scar colour, height, width, texture and whether the scar ‘caught’ on clothing; and clinical evaluation of the width and height of the scar, and its texture, lumpiness, tenderness and colour.

Surgical technique

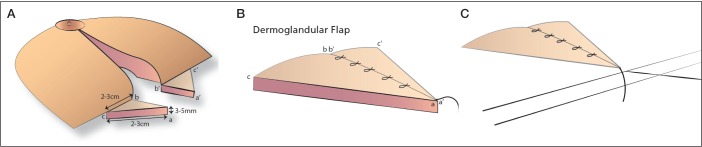

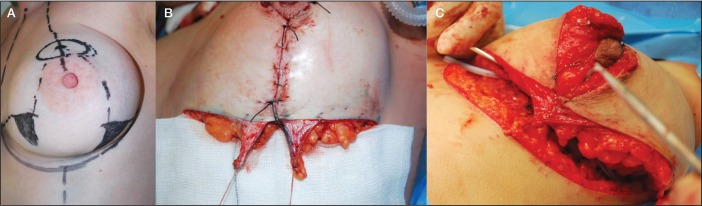

The standard preoperative Wise pattern marking was outlined. Subsequently, caudal to each breast pillar, a triangular zone at the breast meridian zone was marked denoting the future site of the triangular lipodermal flaps (Figures 1 and 2). The patients were anesthetized and positioned in 30° semisitting position under hypotensive anesthesia. A circumareolar incision to isolate the nipple-areola complex (NAC) was performed, and followed by de-epithelialization of NAC dermoglandular flap (superomedial pedicle).

The two designed triangles, each measuring 2 cm to 3 cm depending on breast size, where then de-epithelialized using the knife technique and incised at their margins, leaving the base in continuity with the corresponding breast pillar. Subsequently, each triangle was dissected from the underlying breast parenchyma with a thickness of 3 cm to 5 cm, being thicker toward its base to ensure good vascularization. At this stage, attention was devoted to removing most of the unnecessary subcutaneous fat to avoid future fat necrosis, which can result from tension on these flaps (Figures 1 and 2).

Subsequently, routine dissection and repositioning of the NAC dermoglandular flap followed by resection of excess cutaneous and fibroglandular glandular was performed. The conification of the new breast mound was achieved by suturing the medial and lateral breast pillars together, which substantially approximated the two lipodermal flaps. Absorbable sutures were used to suture the two flaps together. Their apex was then sutured to the musculo-aponeurotic layer of inframammary fold (IMF) at the breast meridian 1 cm below the IMF. This enabled the transfer of most of the tension to the deeper plane rather than the cutaneous plane, providing a tension-free zone at the cutaneous T junction (Figures 1 and 2). Insertion of suction drains (24 h) followed by two-layer closure was performed. However, in the final 18 months of the study (n=33 procedures), drainless reduction mammoplasty was implemented with no repercussions on overall wound healing results. In fact, when compared with patients who had drains, it was, understandably, more comfortable. Subsequently, a sports bra was applied immediately and continued for three weeks.

Figure 1.

Illustrations demonstrating the site, size and thickness of the lipodermal flaps caudal to the each breast pillar at the breast meridian (A); Approximation of medial and lateral lipodermal flaps with interrupted sutures (B). The apical stay suture will be subsequently sutured to the musculo-aponeurotic tissue of the inframammary fold. C The lipodermal flaps secured to the musculo-aponeurotic tissue of inframammary fold approximating the vertical and horizontal axis at the breast meridian

Figure 2.

Intraoperative series showing: A Lipodermal flap outlined caudal to each breast pillar 3 cm in width and length in a patient undergoing unilateral reduction mammoplasty symmetrization. B Lipodermal flaps post de-epithelialisation after conification of the breast mould, note thickness of average 3 mm to 5mm. C Lipodermal flap sutured together with absorbable sutures, note the apical stay suture hinged to the musculo-aponeurotic connective tissue of inframammary fold 1 cm below it at the breast meridian ready to be secured

RESULTS

The weight of resected unilateral breast tissues ranged between 180 g and 1680 g (mean 764 g). In eight (4.6%) procedures, superficial epidermolysis was experienced at the T junction; these were managed conservatively with topical antibiotic and complete re-epithelization was achieved. Full-thickness wound dehiscence developed in five (2.9%) procedures, among them one patient was diabetic and another was on long-term steroid injection for rheumatoid arthritis. The presence of comorbidity in this cohort was statistically insignificant in relation to T-junction complications. Ten of these complicated T-junction procedures occurred in resected breast tissue >764 g (P=0.0733 [Fisher’s exact test]), which was statistically not significant. Nine occurred in patients with a BMI >28.7 kg/m2, which was statistically significant (P=0.0387). The scar width ranged between 2 mm and 11 mm (mean 3 mm). There was no statistical difference whether the procedure was performed as a symmetrization for previous breast cancer treatment versus benign breast hypertrophy (P=0.492). Subjective and objective clinical evaluation revealed that 94% of patients graded their outcome as highly satisfactory.

DISCUSSION

Patient satisfaction after mammoplasty is directly related to the patient’s subjective perception of scar quality. In most of the unsatisfied patients, the scar is aesthetically unacceptable. Numerous modifications have been implemented in various reduction mammoplasty techniques to preserve the function and the geometry of the breast. Techniques with inverted T scar yield a satisfactory cutaneous reduction at both the transverse and vertical aspects but at expense of poor scar quality due to possible risks for cutaneous necrosis at the T junction and loss of breast projection. In the literature, the complication rate varies between 14% and 52%, with wound healing complications representing the most common (5–9). Stevens et al (5) and Zoumaras et al (6) specifically highlighted overall complications with T-junction breakdown as 10% and 39%, respectively. Risk factors, including smoking, diabetes mellitus, high BMI, preoperative breast volume and skin quality, should always be taken into consideration due to the increase risk for wound complications (2,9–11). There has always been an inconsistent relationship between obesity and complications, which may be attributed to the arbitrary definitions used to define obesity including weight, kg over ideal body weight, percent over ideal body weight, BMI and body surface area. Cunningham et al (9) did not report any association between BMI and an increased incidence of complications. This finding was in contrast to Setala et al (7), who noted a significant increase in overall complication rate (52%), with the most common being delayed healing with superficial infection (26%) and skin necrosis or wound dehiscence (18%). Zubowski et al (12) reported an increase of >5% in obese patients. This was consistent with our finding, which showed a statistically significant (P=0.0387) increase in T-junction complication with a BMI >28.7 kg/m2. However, our overall incidence of T-junction wound breakdown was 2.9%, which is lower than what has been reported in the literature. In a prospective study, Menke et al (13) noted an increased complication rate with larger reductions. This correlated with the results of our study in which T-junction morbidity was higher in breast resections >750 g. Overall, this was statistically not significant because T junction morbidity was considerably lower when compared with other published studies due to differences in technique and adherence to selection criteria. De la Plaza et al (11) described a crossed dermal flap technique in WRM, in which two rectangular areas under each breast pillar were de-epithelized and crossed, then fixed to the IMF. They reported that 14% required further surgery to excise small folds in addition to liposuction at the extreme of the scars. Arguably, this could be due to the fact that their technique would lead to bulkiness and unevenness both at the T junction and along the transverse limb due to crossing of these flaps. This could have caused excess undistributed tension, which required further revisional surgeries. In contrast, the triangular lipodermal flaps do not add any bulkiness because most of the subcutaneous fat is denuded, leaving only up to 5 mm thickness. Once sutured, they settle in their normal resting tension-free position; therefore leading to equally distributed tension all over the transverse limb. None of our patients required further surgery to refashion the scars. One of the limitations of Plaza’s technique is that the superomedial pedicle was indicated in mild/moderate hypertrophy and ptosis, while with severe ptosis and gigantomastia, they performed an inferior dermoglandular NAC. This hindered performing the crossed dermal flap safely because incision or complete transection of the base of the NAC inferior pedicle was required. We believe that this would jeopardize the vascularity of the NAC pedicle, which occurred in 2% of their patients. In our study, all patients, including those with gigantomastia, underwent the superomedial pedicle technique. That clearly did not interfere with the execution of the triangular lipodermal flap and no NAC vascular events were recorded. The main aim of the technique described is to create a tension-free zone closure at the T junction to avoid ischemia. This would eventually reduce subsequent wound breakdown and excessive scarring resulting from healing with secondary intention. In addition, it will act as an internal dermal sling, which helps to prevent bottoming out, avoiding loss of breast projection with excellent-quality scars.

CONCLUSION

The triangular lipodermal flap represents an additional valuable modification in the Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty technique, which is simple and versatile. It provides a cutaneous tension-free zone at the inverted T junction and acts as an internal dermal sling, thus providing better wound healing and maintaining breast projection with provision of optimum aesthetic results.

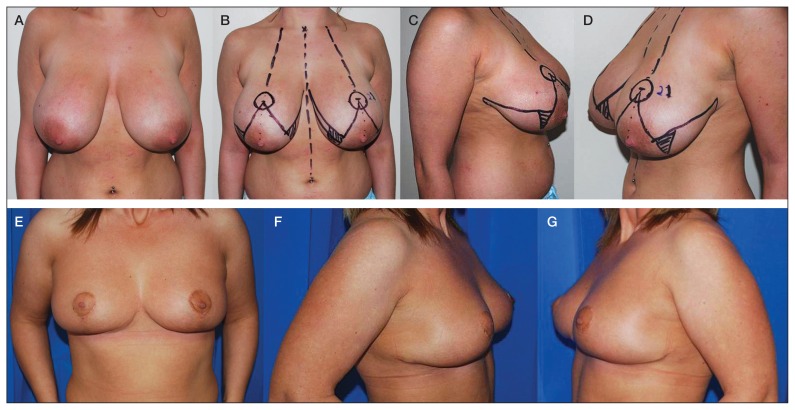

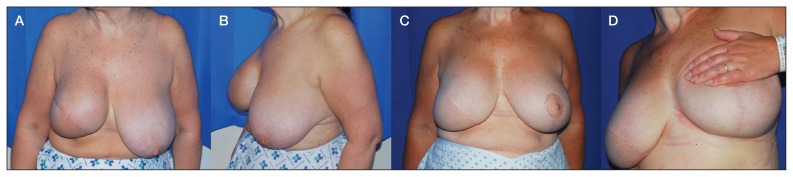

Figure 3.

Case 1, A to D Preoperative anterior and oblique photos of patient with severe benign breast hypertrophy and ptosis showing preoperative markings of the Wise pattern mammoplasty and lipodermal flaps. A total of 1450 g of breast tissue resected. E to G Follow-up anterior and oblique views at 12 months

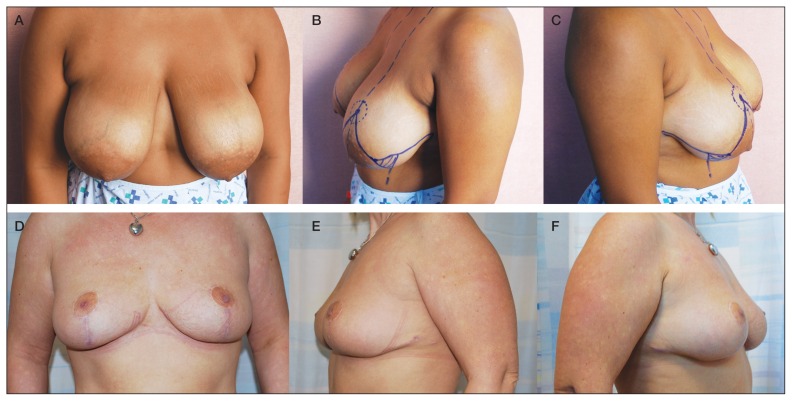

Figure 4.

Case 2, A to C Preoperative anterior and oblique photographs of a patient with severe benign breast hypertrophy and ptosis showing preoperative markings of the Wise pattern mammoplasty and lipodermal flaps in oblique views. D to F A total of 1550 g of breast tissue was resected. Follow-up anterior and oblique views at 12 months

Figure 5.

Case 3, A and B Preoperative anterior and oblique view of a patient (body mass index 32 kg/m2) with previous right breast reconstruction with lattissmus dorsi and implant for breast cancer and contralateral benign breast hypertrophy with severe ptosis. C Anterior view post left reduction mammoplasty symmetrization procedure with excellent shape and symmetry at 18 months (340 g of breast tissue resected). D Close up of the T junction healed with primary intention

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davison SP, Mesbahi AN, Ducic I, Sarcia M, Dayan J, Spear SL. The versatility of the superomedial pedicle with various skin reduction patterns. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1466–76. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000282033.58509.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCulley SJ, Schaverien MV. Superior and superomedial pedicle wise-pattern reduction mammaplasty: Maximizing cosmesis and minimizing complications. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:128–34. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318188d0be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cárdenas-Camarena L. Reduction mammoplasty with superolateral dermoglandular pedicle: Details of 15 years of experience. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:255–61. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31818d45c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mojallal A, Comparin JP, Voulliaume D, Chichery A, Papalia I, Foyatier JL. Reduction mammaplasty using superior pedicle in macromastia. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2005;50:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens WG, Gear AJ, Stoker DA, et al. Outpatient reduction mammaplasty: An eleven-year experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28:171–9. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zoumaras J, Lawrence J. Inverted-T versus vertical scar breast reduction: One surgeon’s 5-year experience with consecutive patients. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28:521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Setala L, Papp A, Joukainen S, et al. Obesity and complications in breast reduction surgery: Are restrictions justified? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:195–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott GR, Carson CL, Borah GL. Maximizing outcomes in breast reduction surgery: A review of 518 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1633–9. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000187145.44732.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham BL, Gear AJ, Kerrigan CL, Collins ED. Analysis of breast reduction complications derived from the BRAVO study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1597–604. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000160695.33457.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartsch RH, Weiss G, Kästenbauer T, et al. Crucial aspects of smoking in wound healing after breast reduction surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1045–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De la Plaza R, De la Cruz L, Moreno C, Soto L. The crossed dermal flaps technique for breast reduction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:383–92. doi: 10.1007/s00266-004-0370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zubowski R, Zins JE, Foray-Kaplon A, et al. Relationship of obesity and specimen weight to complications in reduction mammoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:998–1003. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200010000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menke H, Eisenmann-klein M, Olbrisch RR, Exner K. Continous quality management of breast hypertrophy by the German Association of Plastic Surgeons: A preliminary report. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:594–8. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]