Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease that affects 3.2 percent of the United States population and approximately 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Translational studies have shown that interleukin (IL)-17A, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.2-5 Secukinumab is a fully human, anti-interleukin-17A (IL-17A) monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes IL-17A. The action of secukinumab leads to a decrease in IL-17A levels, dermal inflammatory infiltrate, and epidermal thickening. Clinically, psoriasis patients who have been treated with secukinumab experience significant improvement in their psoriasis disease severity, itching, and quality of life.6-9

Approved Dosing

Clinical trial results have led to the approval of secukinumab for plaque psoriasis in the United States and parts of Europe and Asia in 2015. For example, in the United States, the approved dosing for secukinumab for plaque psoriasis is 300mg subcutaneously every week for the first five weeks and then 300mg subcutaneously every four weeks. As of February 2016, secukinumab has also gained United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

In this article, the authors discuss the findings from the landmark, pivotal trials regarding secukinumab in the treatment of plaque psoriasis: ERASURE (secukinumab vs. placebo), FIXTURE (secukinumab vs. etanercept vs. placebo), and CLEAR (secukinumab vs. ustekinumb). This discussion serves to improve practitioners’ understanding of the clinical trial evidence for secukinumab in psoriasis.

Clinical Evidence

In 2014, Langley et al6 published the landmark paper in The New England Journal of Medicine that introduced IL-17 inhibitors as a key, novel treatment option for plaque psoriasis. In this article, the investigators evaluated the efficacy and safety of secukinumab for moderate-to-severe psoriasis in two Phase 3 studies. The ERASURE (Efficacy of Response and Safety of Two Fixed Secukinumab Regimens in Psoriasis) study evaluated the efficacy of secukinumab versus placebo. In comparison, the FIXTURE (Full Year Investigative Examination of Secukinumab vs. Etanercept Using Two Dosing Regimens to Determine Efficacy in Psoriasis) study evaluated the efficacy of secukinumab versus etanercept and versus placebo.

Secukinumab versus Placebo: the ERASURE study

Primary objective. In the 52-week ERASURE study, the primary objective was to evaluate Week 12 superiority of secukinumab over placebo as measured by two coprimary endpoints: 1) proportion of patients experiencing 75 percent or more reduction in psoriasis severity from baseline using the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (or proportion of patients achieving PASI 75), and 2) proportion of patients achieving 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) on a 5-point modified Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) (scores 0-4).

Study design and study population. The ERASURE study is a randomized, Phase 3, double-blind, 52-week clinical trial that took place between June 2011 through April 2013 at 88 sites worldwide. This study had a screening period of 1 to 4 weeks, an induction period of 12 weeks, a maintenance period of 40 weeks, and a follow-up period of eight weeks.

The inclusion criteria for the study are as follows. To be eligible for the study, the patients had to be 18 years or older with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis that had been diagnosed at least six months before randomization. In addition, their plaque psoriasis had to be poorly controlled with topical treatments, phototherapy, systemic therapy, or a combination of these treatments. Patients had to have a baseline PASI score of 12 or higher, a score of 3 or 4 on the modified IGA, and body surface area (BSA) of 10 percent or greater.

At the beginning of the study, 738 patients with plaque psoriasis were initially randomly assigned to one of three arms: secukinumab 300mg (administered once weekly for 5 weeks, then every 4 weeks), secukinumab 150mg, or placebo.

Across the study groups, the patients’ demographic and baseline clinical characteristics were balanced. In the ERASURE study, the average age of participants were 45 years, 69 percent being male, and 79 percent being Caucasian. The average weight was between 87kg to 90kg, and the body mass index (BMI) averaged 30. Patients had 17 years duration of plaque psoriasis. Among the three study groups, the baseline average PASI score is between 21.4 to 22.5, and the BSA is between 29.7 to 33.3 percent. Approximately two-thirds of patients had a score of 3 (moderate disease) on modified IGA, and one-third had a score of 4 (severe disease) on modified IGA. Between 19 to 27 percent of patients have psoriatic arthritis. Approximately 30 percent of patients were on a previous biologic agent. More patients in the secukinumab groups were previously on a conventional agent (51-52%) compared to placebo group (44%).

Outcomes: Coprimary endpoints and key secondary endpoints. Overall, secukinumab was found to be superior to placebo in all of the coprimary and key secondary endpoints. In addition, the 300mg secukinumab achieved numerically superior response rates with respect to efficacy endpoints compared to the 150mg dose.

Specifically, at the end of 12 weeks, the investigators found that the proportion of patients achieving PASI 75 was 81.6 percent in the secukinumab 300mg arm, 71.6 percent in secukinumab 150mg arm, and 4.5 percent in the placebo arm (P<0.001 for each secukinumab dose vs. placebo). The proportion of patients achieving IGA 0 or 1 was 65.3 percent with secukinumab 300mg, 51.2 percent with secukinumab 150mg, and 2.4 percent with placebo (P<0.001 for each secukinumab dose vs. placebo).

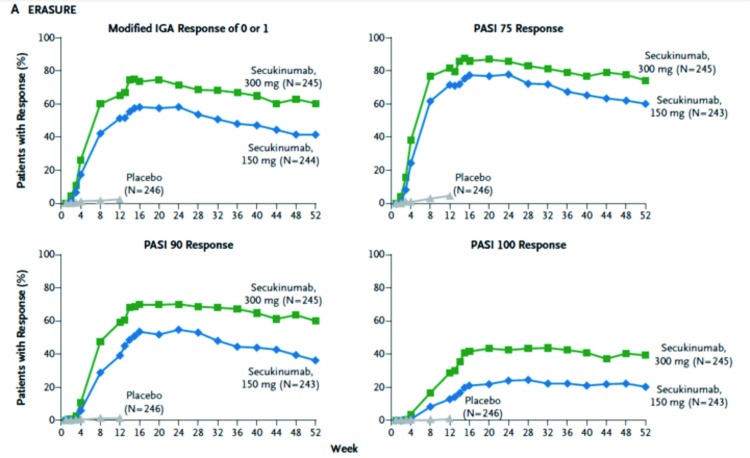

The key secondary endpoints that were assessed were PASI 90, patient-reported psoriasis-related itching, pain, and scaling on the Psoriasis Symptom Diary at Week 12, maintenance of PASI 75 and IGA 0 or 1 from Week 12 through Week 52. The investigators found that the PASI 90 responses at Week 12 were 59 percent, 39 percent, and one percent in patients randomized to secukinumab 300mg, 150mg, and placebo, respectively. The PASI 100 responses at Week 12 were 29 percent, 13 percent, and one percent in patients randomized to secukinumab 300mg, 150mg, and placebo, respectively. Compared to placebo, both doses of secukinumab also had significantly greater response on patient-reported psoriasis-related itching, pain, and scaling on the Psoriasis Symptom Diary (P<0.001). The proportion of patients achieving Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) 0 or 1 was significantly higher in both doses of secukinumab groups compared to placebo (P<0.001). Both doses of secukinumab were also superior to placebo in patient-reported psoriasis-related itching, pain, and scaling. Finally, with regard to maintenance (Figure 1), the peak response rate appears to be achieved at around Week 16, after which the response has stabilized.

Figure 1.

Efficacy through Week 52 in the ERASURE study. This figure shows the maintenance of response with regards to PASI 75, 90, and 100, and IGA 0 or 1 in secukinumab 300mg and 150mg through Week 52.

Adapted from Langley et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326-338.

Safety. Overall, the rates of adverse events were similar between the secukinumab groups and the placebo during the induction period. However, higher proportions of patients with infections were seen in the secukinumab group (29% in the 300mg group and 27% in the 150mg group) compared to placebo (16%). Throughout the study, the most common adverse effects were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory track infection, and headache.

Secukinumab versus Etanercept and versus Placebo: the FIXTURE Study

Primary objective. Similar to the ERASURE study, the primary objective of the 52-week FIXTURE study was to evaluate Week 12 superiority of secukinumab over placebo as measured by two coprimary endpoints: 1) proportion of patients achieving PASI 75, and 2) proportion of patients achieving 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) on the modified IGA.

The key difference between the ERASURE and the FIXTURE study is that, in the FIXTURE study, etanercept was used as one of the comparator arms. This study design is to reflect the different key secondary objectives in the F1XTURE study to compare secukinumab versus etanercept.

Study design and study population. The FIXTURE study is also a randomized Phase 3, double-blind, 52-week clinical trial that took place between June 2011 through June 2013 at 231 sites worldwide. This study had a screening period of 1 to 4 weeks, an induction period of 12 weeks, a maintenance period of 40 weeks, and a follow-up period of eight weeks.

The inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for the FIXTURE study are similar to those of the ERASURE study except that patients who had used etanercept at anytime before screening were excluded.

In the FIXTURE study, 1,306 patients with plaque psoriasis were initially randomly assigned to one of the four arms: secukinumab 300mg (administered once weekly for 5 weeks, then every 4 weeks), secukinumab 150mg, etanercept 50mg (administered twice weekly for 12 weeks and then once weekly), or placebo.

Among the comparison arms in the FIXTURE study, the patients’ demographic and baseline clinical characteristics were similar. Among the groups, the average age of participants ranged between 44 to 45 years; male patients comprised between 69 to 73 percent of the patients; Caucasian patients comprised more than two-thirds of the study population. The average weight of participants ranged between 83 to 85kg, and the BM1 averaged 28. The average baseline PASI score was 24, and the average baseline BSA was between 34 and 35 percent. Approximately 60 percent of patients had a score of 3 (moderate disease) on modified IGA, and 40 percent had a score of 4 (severe disease) on modified IGA. With regards to psoriatic arthritis, 13.5 percent of patients randomized to etanercept and 15 percent of patients randomized secukinumab and placebo had psoriatic arthritis. Between 11 and 14 percent of patients were previously on a biologic in the FIXTURE study.

Outcomes. Coprimary endpoints and key secondary endpoints. Overall, secukinumab was superior to placebo in all of the coprimary and key secondary endpoints; secukinumab was also superior to etanercept with respect to all key secondary endpoints. Similar to the ERASURE study findings, the 300mg dose of secukinumab showed numerically superior response rates compared to the 150mg dose.

Specifically in the FIXTURE study, at the end of 12 weeks, the PASI 75 rates were 77.1 percent in the secukinumab 300mg arm, 67.0 percent in the secukinumab 150mg arm, 44.0 percent in the etanercept arm, and 4.9 percent in the placebo arm (P<0.001 for each secukinumab dose vs. comparators). The proportion of patients with an IGA score of 0 or 1 was significantly higher in each of the secukinumab doses compared to both etanercept and placebo (P<0.001 for each secukinumab dose vs. comparators).

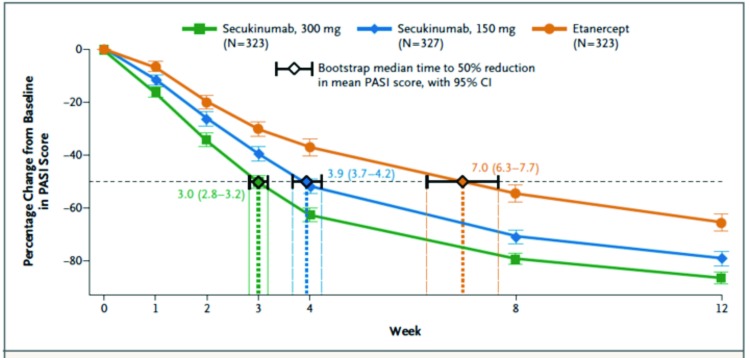

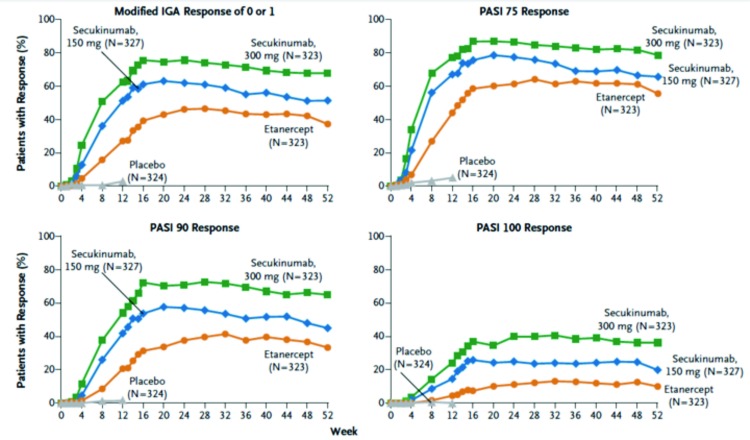

With regard to key secondary endpoints, significantly greater proportions of patients in both doses of secukinumab achieved DLQI of 0 or 1 at Week 12 compared to the etanercept or placebo group (P<0.001 for all comparisons). One key secondary endpoint is assessing the speed of response during the induction period (Figure 2). The investigators found that the median time to a 50-percent reduction in PASI from baseline was significantly shorter in both doses of secukinumab (3 weeks for 300mg secukinumab and 4 weeks for 150mg secukinumab) compared to etanercept (7 weeks) (P<0.001 for both comparisons). With regard to maintenance (Figure 3), the rates of response with regard to achievement of PASI 75, 90, and 100 and IGA of 0 or 1 were higher with secukinumab than etanercept through Week 52.

Figure 2.

Speed of Response in the FIXTURE study. This figure shows median time to 50% reduction in the mean PASI score in the secukinumab and etanercept arms.

Adapted from Langley et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326-338.

Figure 3.

Efficacy through Week 52 in the FIXTURE study. This figure shows maintenance of response with regards to PASI 75, 90, and 100, and IGA 0 or 1 in secukinumab 300mg and150mg groups and etanercept group through Week 52.

Adapted from Langley et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326-338.

Safety. During both the induction and treatment periods of the FIXTURE study, the rates of adverse events were overall similar between the secukinumab and etanercept groups. The most common adverse events in the secukinumab groups were nasopharyngitis, headache, and diarrhea.

Some differences were observed in adverse event rates between secukinumab and etanercept. Though not statistically significant, the rate of injection-site reaction was numerically lower in the secukinumab groups (0.7%) compared to etanercept (11%). Candida infections were more common with secukinumab than with etanercept; however, none resulted in discontinuation of therapy or chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. A higher rate of candidiasis was observed with the 300mg secukinumab group (4.7%) compared to the 150mg secukinumab group (2.3%); all cases of candidiasis resolved on their own or with standard therapy. Of note, very low rates of neutropenia were observed in both the secukinumab groups (1% with Grade 3 neutropenia) and etanercept (0.3% with Grade 4 neutropenia).

Finally, anti-secukinumab antibodies were observed in 0.4% of the secukinumab-treated patients. The antisecukinumab antibodies were not neutralizing, and the antibody presence did not appear to be associated with reduced efficacy or adverse events.

Secukinumab versus Ustekinumab: the CLEAR Study

Thaci et al10 published the 16-week analysis from the CLEAR study, a Phase 3b study comparing the efficacy and safety of secukinumab with ustekinumab.

Primary objective. The primary objective of the CLEAR study was to determine superiority of secukinumab versus ustekinumab using PASI 90 response at Week 16.

Study design and study population. CLEAR is a 52-week, randomized, double-blind, active comparator, parallel-group, superiority Phase 3b study that began in February 2014.

The inclusion criteria were adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis who had been inadequately controlled by topical treatments, phototherapy, and/or previous systemic therapy. The key exclusion criteria were prior exposure to any biologics directly targeting IL-17 inhibitors or ustekinumab. The eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to secukinumab 300mg or ustekinumab (per-label dosing of 45mg for patients ≤100kg and 90mg for patients >100kg).

In the CLEAR study, a total of 676 subjects were randomized. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were balanced between the two study groups. The patients were on average 45 years old, with BM1 of 29; approximately 67 percent of patients have had prior systemic treatment. Slight numeric imbalance was observed in the proportion of patients with psoriatic arthritic, with 21 percent and 16 percent in secukinumab and ustekinumab groups, respectively.

Outcomes: Coprimary endpoints and key secondary endpoints. With regard to the primary endpoint, at Week 16, 79 percent of patients randomized to the secukinumab and 58 percent of those randomized to the ustekinumab group achieved PASI 90 response (P<0.0001). Several key secondary endpoints were also examined. A significantly greater proportion of secukinumab-treated patients achieved PASI 100 response compared to ustekinumab group at Week 16 (44.3% vs. 28.4%, respectively, p<0.0001). Furthermore, a significantly greater proportion of secukinumab-treated patients achieved PASI 75 and IGA 0 or 1 at Week 16 compared to ustekinumab.

With respect to efficacy during the initial treatment period, 50 percent of secukinumab-treated patients achieved PASI 75 at Week 4 compared to 21 percent in the ustekinumab arm (P<0.0001). The superiority in efficacy of secukinumab to ustekinumab was also observed with PASI 90, PASI 100, or IGA 0 or 1 at Week 4. Furthermore, the proportion of patients achieving DLQ1 0 or 1 was significantly higher in the secukinumab-treated patients compared to ustekinumab-treated patients.

Safety. The duration of 16-weeks used in this analysis was likely not long enough to detect rare events or events with long latency periods. Nevertheless, the 16-week safety analysis showed that, overall, secukinumab exhibited a safety profile similar to that of ustekinumab. In addition, the investigators did not observe new or unexpected safety signals that were not observed in the prior Phase 3 trials.

Discussion

The aforementioned studies showed that IL-17A appears to be critical in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Blocking IL-17A ligand leads to excellent clearance of plaque psoriasis and is associated with an acceptable safety profile. A few notable observations remain with the FIXTURE and ERASURE studies. First, compared to the pivotal trials for previously approved biologics, the study population in these secukinumab studies enrolled patients with overall lower average body weight than prior biologic trials. Second, compared to previous pivotal studies with other biologics, the patient population in these two trials has higher baseline BSA involvement and lower rates of psoriatic arthritis.

In the real world where clinical decisions are made in the context of choosing among multiple available agents, it is important to obtain comparative effectiveness data to help guide our clinical decision-making. Randomized controlled studies comparing secukinumab to etanercept and to ustekinumab are highly informative to clinical decision-making.

In conclusion, secukinumab is the first of the IL-17 inhibitor class of biologics to become available to our psoriasis patients. 1ts efficacy has been demonstrated to be outstanding based on its clinical trial data, and its role in treating moderate-to-severe psoriasis is critical. Determining how secukinumab impacts other aspects of the patients’ well-being using patient-reported outcomes is also as important as examining the traditional outcomes assessments based on morphology and BSA alone. The safety of secukinumab appears to be acceptable at this time, but continued surveillance will be necessary to determine its long-term safety.

References

- 1.Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiricozzi A, Suarez-Farinas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Increased expression of interleukin-17 pathway genes in nonlesional skin of moderate-to-severe psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(1):136–145. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J, Oh CH, Jeon J, et al. Molecular phenotyping small (Asian) versus large (Western) plaque psoriasis shows common activation of IL-17 pathway genes but different regulatory gene sets. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(1):161–172. doi: 10.1038/JID.2015.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suarez-Farinas M, Arbeit R, Jiang W, et al. Suppression of molecular inflammatory pathways by Toll-like receptor 7, 8, and 9 antagonists in a model of IL-23-induced skin inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang CQ, Suarez-Farinas M, Nograles KE, et al. IL-17 induces inflammation-associated gene products in blood monocytes, and treatment with ixekizumab reduces their expression in psoriasis patient blood. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(12):2990–2993. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two Phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McInnes IB, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriatic arthritis: a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II proof-of-concept trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(2):349–356. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papp KA, Langley RG, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIÏ dose-ranging study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(2):412–421. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rich P, Sigurgeirsson B, Thaci D, et al. Secukinumab induction and maintenance therapy in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II regimen-finding study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(2):402–411. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thaci D, Blauvelt A, Reich K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]