Abstract

Cullin 4A (CUL4A) overexpression has been reported to be involved in the carcinogenesis and progression of many malignant tumors. However, the role of CUL4A in the progression of gastric cancer (GC) remains unclear. In this study, we explored whether and how CUL4A regulates proinflammatory signaling to promote GC cell invasion. Our results showed that knockdown of CUL4A inhibited GC cell migration and invasion induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. We also found that both CUL4A and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) protein expressions were enhanced by LPS stimulation in HGC27 GC cell lines. Furthermore, knockdown of CUL4A decreased the protein expression of NF-κB and mRNA expression of the downstream genes of the NF-κB pathway, such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2, MMP9, and interleukin-8. Our immunohistochemistry analysis on 50 GC tissue samples also revealed that CUL4A positively correlated with NF-κB expression. Taken together, our findings suggest that CUL4A may promote GC cell invasion by regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway and could be considered as a potential therapeutic target in patients with GC.

Keywords: CUL4A, NF-κB, gastric cancer, invasion

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths after lung and bronchus cancers and is the fourth most common malignancy worldwide.1 In recent years, in spite of a decrease in the rate of GC incidence in some parts of the world, primarily due to early detection and dietary changes, the incidence of GC remains high in China.2 The association between chronic inflammation and GC is now well established. For instance, chronic gastritis is induced by Helicobacter pylori infection, which progresses to atrophy, metaplasia, dysplasia, and GC.3 Therefore, an understanding of the relationship between inflammation and GC is essential for developing prevention and treatment strategies against gastric carcinogenesis.

Members of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) family include the proteins RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p50 and its precursor p105), and NF-κB2 (p52 and its precursor p100); these proteins act as transcription factors and play critical roles in the development of inflammation and cancer.4,5 The NF-κB proteins and other proteins associated with the NF-κB pathway have been reported to be involved in many cell physiological functions, including apoptosis, proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis.6 In cells in resting state, NF-κB proteins are mainly localized in the cytoplasm with a heterotrimeric complex, composed of the p50, p65, and IκBα proteins. Various stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), and IL-1β trigger a signaling cascade through receptor-induced signaling to activate NF-κB proteins. The process of activation includes phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation of IκBα and phosphorylation of p65. Then, the phosphorylated p65 translocates into the nucleus.7 Once inside the nucleus, it binds to its cognate DNA-binding site in the promoter or enhancer regions of specific genes, thereby switching on their expression.8,9 Owing to their physiological importance, the NF-κB proteins have come to be regarded as key integrators of immunity, inflammation, and oncogenesis. Cellular levels of NF-κB are constitutively elevated in many human tumors that are preceded by chronic inflammation. For instance, GC is driven by H. pylori infection.10 Meanwhile, Sasaki et al11 had proved that NF-κB was constitutively activated in human gastric tissue and contributed to the aggressiveness of gastric carcinoma. However, the mechanism how NF-κB is involved in GC remains largely unknown.

Cullin 4A (CUL4A) is a member of the cullin family of proteins comprising the multifunctional ubiquitin ligase E3 complex and plays critical roles in DNA replication, cell cycle regulation, and genomic instability through the ubiquitin–proteasome system.12–17 CUL4A amplification or overexpression has been reported in certain human cancers, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, childhood medulloblastoma, prostate cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma,18–23 and is associated with poor prognosis in node-negative breast cancer.18 These data suggest that CUL4A could play an important role in the progression of malignant tumors. In addition, CUL4B, a homolog of CUL4A, is known to exhibit functional redundancy with CUL4A.17,24 CUL4B has been demonstrated to be involved in the immune system processes and regulation of proinflammatory cytokines.25,26 Thus, it can be speculated that CUL4A may act as an oncogene; however, whether it plays any role in inflammation remains unknown.

In numerous studies, ubiquitin modification has been shown to play a crucial role in NF-κB signaling activation. For instance, the phosphorylation target IκBα, which can inhibit the activation of NF-κB proteins, is ubiquitinated by the SCF-ubiquitin ligase complex.27–29 CUL4A is a core component in the multifunctional ubiquitin ligase E3 complex; therefore, we hypothesized that overexpression of CUL4A may promote GC cell invasion by activating the NF-κB pathway. In this research, we demonstrated that downregulation of CUL4A expression leads to the inhibition of GC cell invasion induced by LPS stimulation. Furthermore, knockdown of CUL4A decreases the expression of NF-κB and its downstream target genes. These results indicate that CUL4A/NF-κB signaling may be involved in the invasion of GC.

Patients and methods

Ethics statement

All the patients agreed to participate in our study and gave written informed consent. The study and the ethical consent forms were approved by the ethical board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients and clinical specimens

The postoperative GC samples were provided by The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. Paraffin-embedded, archived GC samples were collected from 50 patients diagnosed with GC between January 2007 and December 2010. According to the seventh edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor node metastasis staging system, there were 16 patients in stage II and 34 patients in stage III. The surgical specimens were fresh tissue samples that were frozen in liquid nitrogen within 20 min after collection. The primary GC tissues and adjacent normal tissues were collected from patients who underwent therapeutic surgery, with informed consent.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections (4 mm thick) were deparaffinized and rehydrated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the sections in citrate buffer at 95°C for 1 h. After blocking endogenous peroxidase with 3% hydrogen peroxide, tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies against CUL4A (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and NF-κB (1:50; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MS, USA). After washing three times with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), a biotinylated secondary antibody (Zhongshan Bio-Tech, Beijing, People’s Republic of China) was added (1:100) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Tissue sections were developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin. The rate of staining intensity was scored as 0 (no staining), 1 (light yellow), 2 (yellow brown), and 3 (brownish yellow staining). The positively stained tumor cells were graded as 0 (no positively stained cells), 1 (<10% of positive cells), 2 (10–50% of positive cells), and 3 (>50% of positive cells). The immunostaining index was calculated as the rate of positively stained tumor cells multiplied by the staining intensity score; tumors with indexes 0–4 were considered negative, and those with indexes 5–9 were considered positive.

Cell culture and transfection

Human GC HGC27 cells (presented by The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Solarbio, Beijing, People’s Republic of China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Transgene, Illkirch Graffenstaden, France) and 1% antibiotics. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting the CUL4A gene and nonsense siRNA (for the use as negative control [NC]) were designed and synthesized (GenePharma, Shanghai, China). The HGC27 cells were grown to 30–40% confluence and transfected with CUL4A siRNA or NC. Transfection efficiency was determined using Western blot and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and quantitative real-time- polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from the transfected cell lines was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), and reverse transcribed to cDNA using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, People’s Republic of China). Real-time PCR was performed using the qPCR SuperMix (Takara Co, Minamikusatsu, Japan) and StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) using a standardized protocol. Calculation of target RNA levels was based on the CT method and normalized to β-actin expression. All reactions were run in triplicate over multiple days. Information about primer sequences is summarized and presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The sequences of primers for quantitative real-time PCR

| Gene | Primers | |

|---|---|---|

| CUL4A | F: GGAAAGCACAGTGGTCGAA | R: GGGACACCTGGAATTCCTTC |

| IL-8 | F: GGTGCAGTTTTGCCAAGGAG | R: TTCCTTGGGGTCCAGACAGA |

| MMP2 | F: CAAGGAGAGCTGCAACCTGT | R: TCTGGGGCAGTCCAAAGAAC |

| MMP9 | F: GTACTCGACCTGTACCAGCG | R: AGAAGCCCCACTTCTTGTCG |

| VEGF | F: CTGGAGCGTGTACGTTGGT | R: TTTAACTCAAGCTGCCTCGC |

| β-Actin | F: CCTAGGCACCAGGTGTGAT | R: TTGGTGACAATGCCGTGTTC |

Abbreviations: CUL4A, cullin 4A; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; IL-8, interleukin-8; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor, PCR, polymerase chain reaction; F, forward; R, reverse.

Western blot

The proteins used for Western blotting were extracted from the HGC27 cell line or fresh frozen tissues and lysed by an ice-cold lysis buffer. Proteins were separated by 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk or BSA for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight with primary antibodies against CUL4A, NF-κB, and β-actin (Affinity, Cincinnati, OH, USA). After washing three times in TBS/0.05% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated with secondary peroxidase-conjugated antibody (ZSGB, Beijing, People’s Republic of China) for 1 h and washed three times. Signals were detected using the chemiluminescence dissolvent (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA).

Transwell assays

Cell invasion assays were performed using 8 μm transwell inserts (CoStar, Corning, NY, USA) coated with 60 μL of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cells were added to the upper chamber with 200 μL of serum-free medium, and 600 μL of medium containing 25% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added to the lower chamber, following which the cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

Wound healing assays

Cells were seeded into six-well plates and were allowed to grow until a density of ~5×106 cells/well was reached. The cells were denuded by dragging a rubber policeman (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) through the center of the plate. Cultures were rinsed with PBS and replaced with fresh serum-free medium alone or containing 10% FBS, following which the cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Photographs were taken at 0 and 24 h, and the cell migration distance was measured.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables, and a value of P<0.05 was considered as significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS Version 13.0 software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

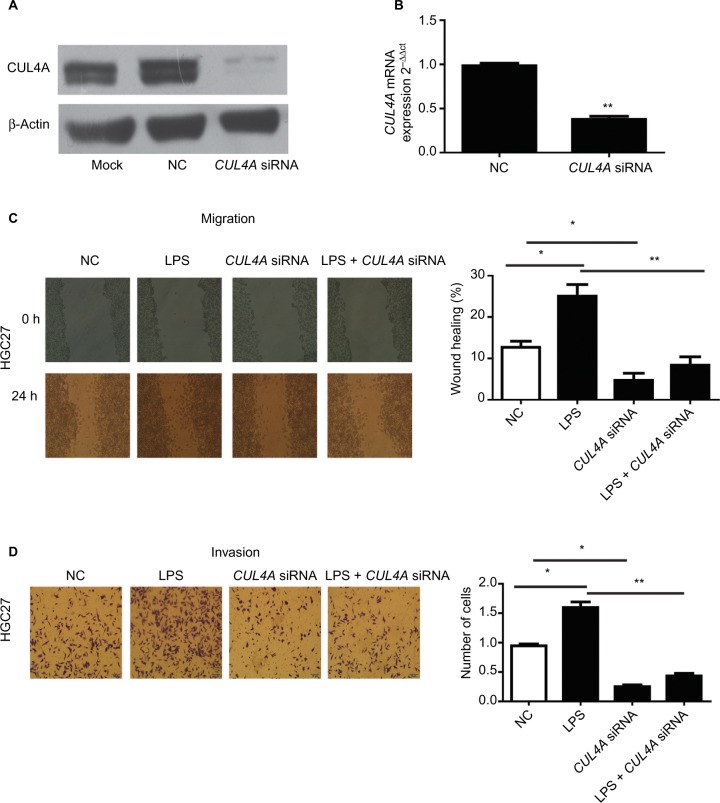

The specific siRNA inhibited CUL4A expression in HGC27 cells

We first tested the efficiency of our siRNA construct in knocking down CUL4A expression in HGC27 cells. Here, HGC27 cells were transfected with CUL4A siRNA for 24 h. Western blotting and qRT-PCR analysis showed that CUL4A expression was significantly reduced at both the protein and mRNA levels in GC cells transfected with CUL4A siRNA compared to control cells (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

The CUL4A siRNA suppressed the expression of CUL4A in HGC27 cells.

Notes: (A) The expression of CUL4A protein in HGC27 cells was measured by Western blot. (B) The expression of CUL4A mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR. CUL4A knockdown inhibited the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells stimulated with LPS. (C and D) After LPS stimulation, the number of migratory and invasive cells was significantly higher than that of HGC27 cells transfected with NC, the number of migratory and invasive cells transfected by CUL4A siRNA was significantly lower than NC, and the number of cells with LPS stimulation was significantly higher than that of CUL4A siRNA-transfected cells stimulated by LPS. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: CUL4A, cullin 4A; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NC, negative control; siRNA, short interfering RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction.

CUL4A knockdown inhibited LPS-induced migration and invasion of GC cells

We performed wound healing assays and transwell assays to determine whether CUL4A knockdown had any inhibitory effect on GC cell migration and invasion induced by LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) stimulation. After LPS stimulation, the number of migratory and invasive cells was significantly higher than that of HGC27 cells transfected with NC, whereas the number of migratory and invasive cells transfected by CUL4A siRNA was significantly lower than NC (Figure 1C and D). Moreover, the number of cells with LPS stimulation was significantly higher than that of CUL4A siRNA-transfected cells stimulated by LPS (Figure 1C and D). This indicated that knockdown of CUL4A could partly suppress the migratory and invasive abilities of GC cells induced by LPS stimulation.

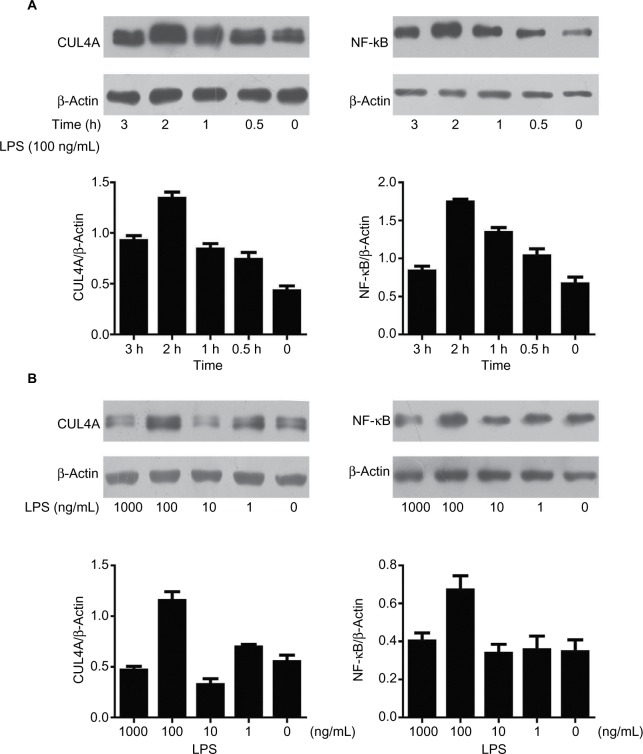

LPS enhanced the expression of CUL4A and NF-κB proteins in GC cells

The effect of LPS on CUL4A and NF-κB protein expressions in GC cells was examined by Western blotting. When cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL of LPS for 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h, CUL4A levels showed a time-dependent increase up to 2 h (Figure 2A). When various LPS concentrations were tested, CUL4A was upregulated in a concentration-dependent manner up to 100 ng/mL (Figure 2B). Similarly, we also investigated time- and concentration-dependent effects of LPS on NF-κB expression in GC cells. Similar to CUL4A, NF-κB expression was also upregulated by LPS in a concentration-dependent manner up to 100 ng/mL at 2 h (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

LPS enhanced the expression of CUL4A and NF-κB proteins in gastric cancer cells.

Notes: (A) HGC27 cells were stimulated for different durations with 100 ng/mL LPS, and the protein levels of CUL4A and NF-κB were investigated by immunoblotting. (B) Gastric cancer cells were cultured with various LPS concentrations for 2 h, and CUL4A and NF-κB expression were analyzed by Western blotting.

Abbreviations: CUL4A, cullin 4A; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B.

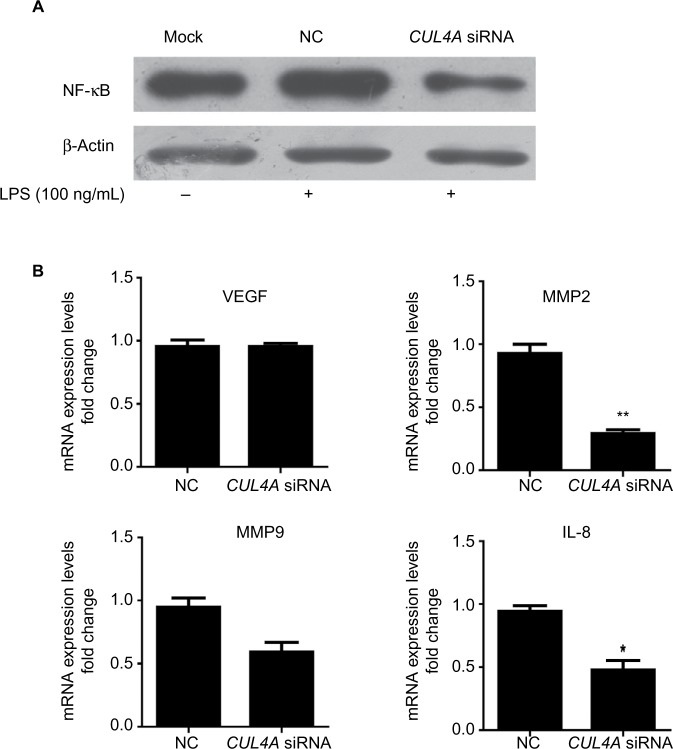

Knockdown of CUL4A inhibited the NF-κB pathway

To investigate the role of CUL4A in NF-κB signaling pathway, we downregulated CUL4A expression with siRNA and observed a significant reduction in NF-κB protein expression in HGC27 cells stimulated by LPS (Figure 3A). In cells where CUL4A was downregulated, we also evaluated mRNA expression of the downstream genes of the NF-κB pathway, such as VEGF, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2, MMP9, and interleukin-8 (IL-8). A significant decrease in MMP2, MMP9, and IL-8 mRNA levels was detected in GC cells transfected with CUL4A siRNA compared to those transfected with scrambled siRNA (NC) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Knockdown of CUL4A inhibited the NF-κB pathway.

Notes: (A) HGC27 cells transfected with CUL4A siRNA were treated with 100 ng/mL of LPS for 2 h and analyzed for NF-κB protein levels by immunoblotting. (B) The expression of NF-κB downstream genes including VEGF, MMP2, MMP9, and IL-8 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: CUL4A, cullin 4A; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; IL-8, interleukin-8; NC, negative control; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; siRNA, short interfering RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction.

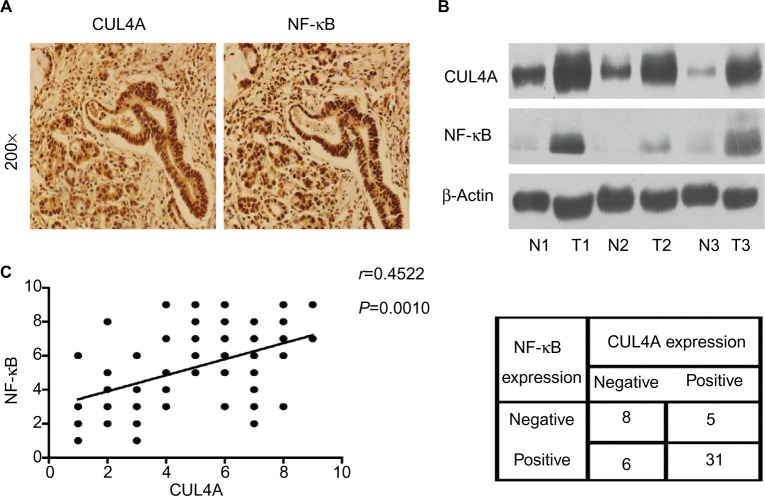

CUL4A and NF-κB were overexpressed in GC tissues

Immunohistochemistry analysis was performed on 50 GC tissue samples to detect CUL4A and NF-κB expressions. Positive expression of CUL4A protein was defined as a medium brown or brownish-yellow stain in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus of tumor tissues, and NF-κB was mainly localized in the nucleus (Figure 4A). In the samples from stage II patients, the positive expression rate of CUL4A and NF-κB proteins was 43.7% (7/16) and 56.2% (9/16), respectively, which was elevated to 85.3% (29/34) and 82.4% (28/34) each in stage III patients. Then, we detected CUL4A and NF-κB expressions in three pairs of GC tissue samples and adjacent nontumor tissue samples via Western blot analysis (Figure 4B). Correlation analysis revealed that CUL4A positively correlated with NF-κB expression (Figure 4C, P=0.0010, r=0.4522).

Figure 4.

CUL4A and NF-κB were overexpressed in GC tissues.

Notes: (A) Representative images of gastric tumor tissues showing concordant positive staining of CUL4A and NF-κB in the same sample (200×). (B) Western blot analysis of CUL4A and NF-κB expressions in three paired primary GC and adjacent noncancerous tissue samples. These three patients were all diagnosed stage III. (C) CUL4A expression scores and NF-κB expression scores in 50 GC samples revealed that CUL4A expression positively correlated with NF-κB expression via correlation analysis (P=0.0010, r=0.4522).

Abbreviations: CUL4A, cullin 4A; GC, gastric cancer; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the role of CUL4A, a ubiquitin ligase protein, in GC cells and found that decreased expression of CUL4A could inhibit the LPS-induced invasion and migration of GC cells. Further investigation revealed that LPS could induce the expression of CUL4A and activate NF-κB expression. In addition, knockdown of CUL4A could decrease the expression of NF-κB and NF-κB downstream genes, including MMP2, MMP9, and IL-8, in GC cells. Furthermore, we detected the expression of CUL4A and NF-κB in fresh GC tissue samples and found that both CUL4A and NF-κB were overexpressed in these samples compared to normal controls. Correlation analysis revealed that CUL4A expression positively correlated with NF-κB expression, based on immunohistochemistry scores. These results suggest that dysregulation of CUL4A may be involved in the invasion of GC via the NF-κB signaling pathway.

In our previous study, we found that CUL4A expression was upregulated in GC tissues and cell lines and that it was associated with poor prognosis in patients with GC.30 In the present study, we also found that CUL4A expression was frequently increased in human GC tissues when compared with normal gastric tissues. Schindl et al demonstrated that overexpression of CUL4A in breast carcinomas was associated with shorter overall and disease-free survival in patients with breast cancer.20 High levels of CUL4A expression have also been detected in various other tumors as well.18,19,21–23 On the basis of this evidence, it can be speculated that CUL4A plays an important role in tumor invasion and metastasis. In early studies, CUL4A was regarded as a potential oncogene based on its ability to ubiquitinate and degrade several well-known tumor suppressor genes, such as p21, p27, DDB2, and p53.14,15,31,32 For instance, Li et al15 showed that the CUL4A ubiquitin ligase targets p27 for degradation and promotes the proliferation of erythroid progenitors and proerythroblasts. In a study by Zemmoura et al,33 decreased expression of p53 resulting from ubiquitination by CUL4A was found to be positively related to the invasiveness of pituitary adenomas. In this study, however, we demonstrated that knockdown of CUL4A could inhibit the invasion of GC cells and suppress the expression of NF-κB and the downstream genes of NF-κB signaling pathway. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report indicating that CUL4A could be involved in the invasion of GC by regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway.

It is well known that NF-κB is an important transcription factor that plays a critical role in the development of inflammation and cancer. In addition, it has been reported to be involved in many physiological functions of the cell, including apoptosis, proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis.34 It is widely reported that NF-κB activation is associated with chronic gastric inflammation and GC.35 In this report, our results show that the expression of CUL4A could be upregulated in GC cells following LPS stimulation. LPS stimulation has been demonstrated to promote tumorigenesis, invasion, or metastasis in various cancers, such as breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic cancer.36–39 We also found that CUL4A expression was positively correlated with NF-κB expression in GC tissues. Both CUL4A and NF-κB were expressed more frequently in stage III GC patients than in stage II patients. Furthermore, after CUL4A expression was downregulated, the expression of NF-κB and the downstream genes of NF-κB pathway, such as MMP2, MMP9, and IL-8, were also inhibited. MMPs belong to the family of endopeptidases, which play important roles in degrading the extracellular matrix (ECM).40 Among the GC MMP family, MMP2 and MMP9 are considered the most important for degrading basement membrane type IV collagen and are associated with invasive, aggressive, or metastatic tumor phenotypes.41–43 Meanwhile, previous studies have demonstrated that IL-8, a potent proinflammatory chemokine derived from monocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells, promotes the adhesion, migration, invasion, and chemoresistance of GC cells.44,45 In conjunction with these reports, our results suggest that CUL4A could promote GC invasion by regulating the NF-κB pathway with inflammatory stimulation.

Conclusion

This is the first report to provide evidence that CUL4A may promote GC cell invasion via NF-κB signaling pathway. Therefore, targeting the newly recognized CUL4A/NF-κB signaling pathway may be a promising strategy for the treatment of GC. CUL4A may serve as a potential biomarker for GC progression, and become a therapeutic target of GC, but its clinical value still needs to be validated in a large cohort of GC samples.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Jiangxi Province Talent 555 Project, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos 81441083 and 81660402), and a grant from the Science and Technology Department of Jiangxi Province (no 20161ACB21018).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Levi F, et al. Recent patterns in gastric cancer: a global overview. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(3):666–673. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Sun WH, et al. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25(suppl 1):S186–S197. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199700001-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urban MB, Schreck R, Baeuerle PA. NF-kappa B contacts DNA by a heterodimer of the p50 and p65 subunit. EMBO J. 1991;10(7):1817–1825. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fantini MC, Pallone F. Cytokines: from gut inflammation to colorectal cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9(5):375–380. doi: 10.2174/138945008784221206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta SC, Kim JH, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Regulation of survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis of tumor cells through modulation of inflammatory pathways by nutraceuticals. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(3):405–434. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M. NF-kappaB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2012;246(1):379–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW. NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(4):301–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A, Takada Y, Boriek AM, Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB: its role in health and disease. J Mol Med. 2004;82(7):434–448. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0555-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pacifico F, Leonardi A. NF-kappaB in solid tumors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72(9):1142–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasaki N, Morisaki T, Hashizume K, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB p65 (RelA) transcription factor is constitutively activated in human gastric carcinoma tissue. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(12):4136–4142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Zhou P. Pathogenic role of the CRL4 ubiquitin ligase in human disease. Front Oncol. 2012;2:21. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugasawa K. The CUL4 enigma: culling DNA repair factors. Mol Cell. 2009;34(4):403–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nag A, Bagchi S, Raychaudhuri P. Cul4A physically associates with MDM2 and participates in the proteolysis of p53. Cancer Res. 2004;64(22):8152–8155. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li B, Jia N, Kapur R, Chun KT. Cul4A targets p27 for degradation and regulates proliferation, cell cycle exit, and differentiation during erythropoiesis. Blood. 2006;107(11):4291–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishitani H, Shiomi Y, Iida H, Michishita M, Takami T, Tsurimoto T. CDK inhibitor p21 is degraded by a proliferating cell nuclear antigen-coupled Cul4-DDB1Cdt2 pathway during S phase and after UV irradiation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(43):29045–29052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806045200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu J, Xiong Y. An evolutionarily conserved function of proliferating cell nuclear antigen for Cdt1 degradation by the Cul4-Ddb1 ubiquitin ligase in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(7):3753–3756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LC, Manjeshwar S, Lu Y, et al. The human homologue for the Caenorhabditis elegans cul-4 gene is amplified and overexpressed in primary breast cancers. Cancer Res. 1998;58(16):3677–3683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasui K, Arii S, Zhao C, et al. TFDP1, CUL4A, and CDC16 identified as targets for amplification at 13q34 in hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 2002;35(6):1476–1484. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schindl M, Gnant M, Schoppmann SF, Horvat R, Birner P. Overexpression of the human homologue for Caenorhabditis elegans cul-4 gene is associated with poor outcome in node-negative breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(2):949–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L, Lee S, Zhang J, et al. CUL4A abrogation augments DNA damage response and protection against skin carcinogenesis. Mol Cell. 2009;34(4):451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birner P, Schoppmann A, Schindl M, et al. Human homologue for Caenorhabditis elegans CUL-4 protein overexpression is associated with malignant potential of epithelial ovarian tumours and poor outcome in carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(6):507–511. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren S, Xu C, Cui Z, et al. Oncogenic CUL4A determines the response to thalidomide treatment in prostate cancer. J Mol Med. 2012;90(10):1121–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0885-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higa LA, Mihaylov IS, Banks DP, Zheng J, Zhang H. Radiation-mediated proteolysis of CDT1 by CUL4-ROC1 and CSN complexes constitutes a new checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(11):1008–1015. doi: 10.1038/ncb1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung MH, Jian YR, Tsao CC, Lin SW, Chuang YH. Enhanced LPS-induced peritonitis in mice deficiency of cullin 4B in macrophages. Genes Immun. 2014;15(6):404–412. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeiffer JR, Brooks SA. Cullin 4B is recruited to tristetraprolin-containing messenger ribonucleoproteins and regulates TNF-alpha mRNA polysome loading. J Immunol. 2012;188(4):1828–1839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben-Neriah Y. Regulatory functions of ubiquitination in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(1):20–26. doi: 10.1038/ni0102-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson KD. Signal transduction: aspirin, ubiquitin and cancer. Nature. 2003;424(6950):738–739. doi: 10.1038/424738a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu S, Chen ZJ. Expanding role of ubiquitination in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Res. 2011;21(1):6–21. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng J, Lei W, Xiang X, et al. Cullin 4A (CUL4A), a direct target of miR-9 and miR-137, promotes gastric cancer proliferation and invasion by regulating the Hippo signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7(9):10037–10050. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bondar T, Kalinina A, Khair L, et al. Cul4A and DDB1 associate with Skp2 to target p27Kip1 for proteolysis involving the COP9 signalosome. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(7):2531–2539. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2531-2539.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higa LA, Yang X, Zheng J, et al. Involvement of CUL4 ubiquitin E3 ligases in regulating CDK inhibitors Dacapo/p27Kip1 and cyclin E degradation. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(1):71–77. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.1.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zemmoura I, Wierinckx A, Vasiljevic A, Jan M, Trouillas J, Francois P. Aggressive and malignant prolactin pituitary tumors: pathological diagnosis and patient management. Pituitary. 2013;16(4):515–522. doi: 10.1007/s11102-012-0448-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441(7092):431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiba T, Marusawa H, Matsumoto Y, Takai A. Chronic inflammation and gastric cancer development. Nihon Rinsho Jpn J Clin Med. 2012;70(10):1694–1698. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Y, Kong X, Li X, et al. Metadherin mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e29363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melkamu T, Qian X, Upadhyaya P, O’Sullivan MG, Kassie F. Lipopolysaccharide enhances mouse lung tumorigenesis: a model for inflammation-driven lung cancer. Vet Pathol. 2013;50(5):895–902. doi: 10.1177/0300985813476061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu G, Huang Q, Huang Y, et al. Lipopolysaccharide increases the release of VEGF-C that enhances cell motility and promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis through the TLR4-NF-kappaB/JNK pathways in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(45):73711–73724. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Y, Lu J, Antony S, et al. Activation of TLR4 is required for the synergistic induction of dual oxidase 2 and dual oxidase A2 by IFN-gamma and lipopolysaccharide in human pancreatic cancer cell lines. J Immunol. 2013;190(4):1859–1872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liotta LA, Steeg PS, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Cancer metastasis and angiogenesis: an imbalance of positive and negative regulation. Cell. 1991;64(2):327–336. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90642-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stetler-Stevenson WG. Type IV collagenases in tumor invasion and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1990;9(4):289–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00049520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noel A, Emonard H, Polette M, Birembaut P, Foidart JM. Role of matrix, fibroblasts and type IV collagenases in tumor progression and invasion. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190(9–10):934–941. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cockett MI, Murphy G, Birch ML, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases and metastatic cancer. Biochem Soc Symp. 1998;63:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zouki C, Jozsef L, Ouellet S, Paquette Y, Filep JG. Peroxynitrite mediates cytokine-induced IL-8 gene expression and production by human leukocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69(5):815–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuai WX, Wang Q, Yang XZ, Zhao Y, Yu R, Tang XJ. Interleukin-8 associates with adhesion, migration, invasion and chemosensitivity of human gastric cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(9):979–985. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i9.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]