Patient-centred care is the concept of 'informing and involving patients, responding quickly and effectively to patients' needs and wishes, and ensuring that patients are treated in a dignified and supportive manner'.1 It is a popular talking-point at present, having been brought into the limelight by the Bristol inquiry,2 but it is not new. Balint in the 1950s was proposing that doctors put more emphasis on listening to what the patient was trying to say behind the simple presenting complaint.3 Pendleton and colleagues in the 1980s were strong proponents of the notion that communication skills are the basis of fruitful consultations4—another way of saying that the patient's perspective is important. Indeed most medical readers of this article, if they became 'patients', would wish to be actively involved in the management of their illness. Patients are increasingly coming to be seen as consumers of healthcare, with rights like those of any other consumer. As Richard Smith, editor of the BMJ, has put it:'There is no ”truth” defined by experts. Rather there are many opinions.... Doctors might hanker after a world where their view is dominant. But that world is disappearing fast'.5 Persuasive evidence that patient-centred care helps patients has been published—for instance, reduction in blood pressure was greater in patients who, during visits to the doctor, had been allowed to express their health concerns without interruptions;6 and, in patients with headache, improvement was most likely in those enabled to discuss their condition in full.7 There is also, admittedly, some evidence to the contrary: patients randomized to receive diabetes care from workers trained in patient-centred care did worse than the comparison group in some clinical measures (though they were more satisfied with their treatment).8

IF NOT PATIENT-CENTRED, WHAT ELSE?

Doctor-centred care

In doctor-centred care the assumption is that the doctor knows best, will act in the patient's best interest, and should thus dominate the relationship. Another word for this model is medical paternalism, and there are circumstances in which it can be defended. For example, in National Health Service hospitals patients do not, generally, have the chance to choose what doctor they see or who does their operation. The agenda is, in the short term, driven by doctors' needs, although the policy may have long-term benefits for patients as a whole. Another place for paternalism is where the patient seems to desire this approach, and one might expect this to apply to older patients who have experienced doctor-controlled consultations through most of their lives. This could be wrong: in one study of older patients with coronary heart disease there was considerable dissatisfaction with the lack of proper communication.9 The personality of the patient is probably more important than age: those with a 'submissive' trait are most likely to favour paternalism. Some general practitioners say they keep patient-centred care as a tool in their back pocket, to be used in certain circumstances with selected patients.

Public-health-centred care

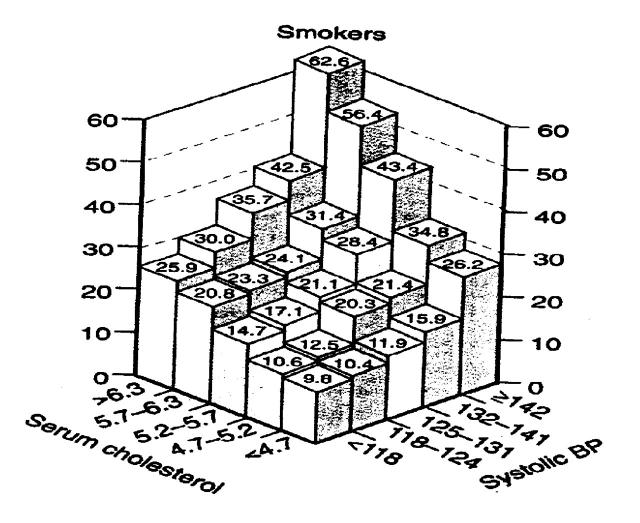

Some doctor–patient interactions are driven by public health considerations. A prime example is immunization. The MMR controversy is generating considerable disquiet among some parents, and the patient-centred approach would normally mean immediate acquiescence to a parent's refusal of the triple vaccine. However, this would have implications for the public good, and a doctor might see a duty to outline the facts of the case as presented by the Department of Health.10 More subtle public health arguments enter into other types of healthcare. For example, treatment of moderately raised blood pressure may usefully reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease in the population overall, but for the individual the benefits are much less obvious. Best evidence suggests that the number needed to treat (NNT) in order to prevent one stroke in patients with isolated systolic hypertension is about 55, and about the same for coronary heart disease. NNT for prevention of one death is about 100.11 These may not seem very favourable odds for the individual who, by accepting treatment, becomes medicalized (a 'patient' condemned to lifelong medication, with a risk of side-effects). The doctor is left with a dilemma as to how to manage the patient in his/her best interest. A further difficulty with hypertension and cardiovascular disease is relevant to this whole argument—presentation and understanding of risk. This is not simply a matter of understanding statistics.12 We need to factor in the 'horror' associated with the risk, which is intensely personal and difficult to quantify. Doctors must grapple with this, since treatment decisions for doctor and patient depend on perception of risk. In the case of hypertension, risk of cardiovascular disease depends on the interrelation with numerous other risk factors (Figure 1). How best to get such complex information over to the patient, and thus enable a truly informed choice, is a perplexing question.

Figure 1.

Risk of mortality (expressed per 10 000 person years on the y axis) from coronary heart disease and stroke in relation to various risk factors in persons recruited to the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) (Ref. 13)

Clinical quality assurance

Some would argue that a system to guarantee high clinical quality is the most important part of any doctor–patient interaction.14 In some circumstances (e.g. acute shock or serious road traffic accident), most patients would surely wish the healthcare worker to take over and act in what is perceived to be their best interest, as rapidly as possible. In most interactions, however, decisions are less urgent and the patient's and doctor's perspectives should go hand in hand.

WHAT ARE THE BARRIERS TO PATIENT-CENTRED CARE?

There are three important barriers to patient-centred care.

Time

The average consultation in general practice lasts 7–8 minutes. In hospital, it is often not much longer. According to Gask and Usherwood,15 the main tasks in a medical consultation are to build a relationship, collect data, and agree a management plan. The prominence of each of these elements in an individual consultation will vary, and it is not necessarily desirable to cover all aspects in one session. However, pressure on health services is such that multiple consultations to cover all the ground may not be feasible (the same doctor may not be available next time, there may be no appointment free at the desired interval, and so on). The time taken to gather data and agree a management plan will depend on the baseline knowledge of the patient, his or her level of intelligence, the doctor's and the patient's ability to communicate effectively, and the complexity of the patient's problems. Many general practice consultations are multifaceted, with social as well as medical issues to be tackled. It is difficult to see how these facts of life can be reconciled with a patient-centred but time-limited approach.

Motivation

I believe that most doctors would wish to pursue a patient-centred agenda as far as possible. It accords with underlying motives for becoming a doctor such as altruism and beneficence. However, pressures of work may make the paternalistic approach seem more attractive. To lay down the law is usually easier and quicker: 'this is the ideal pill/operation for you, and you will be better in two weeks'—end of consultation. Even if, at the beginning of a surgery or clinic, we recognize the potential fallibility of such an approach and make a conscious effort to avoid it, 2 hours later the resolution may have slipped. Tiredness is a debilitating state, both for patient and for doctor.

Wisdom

'Zeal without knowledge is fire without light'—proverb. 'Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers'—Tennyson.

Management of medical problems requires knowledge and wisdom on the part of both patient and doctor. The doctor is expected to have medical expertise, but the patient is the person with direct experience of the disease and how it relates to his or her social circumstances and values. Patient-centred care demands a marriage of these two sides of knowledge, and the acquisition of wisdom as a result. Some patients have considerable medical knowledge as a result of their personal experiences and reading, but they are not necessarily wise about management. Equally, there are doctors who have very little knowledge about diseases but try to appear wise about them, and doctors who have ample theoretical knowledge but too little experience to have gained wisdom. Such mismatches demand intellectual honesty from both parties, and often agreement to seek help elsewhere. Most patients, however, are ill-informed about their illness, and easy-to-understand and up-to-date information will help them towards more fruitful discussion with their doctors. The internet may be one answer, though it is full of conflicting information and not all patients are computer literate. Such information can also be supplied, at the cost of some effort, from doctors' surgeries and hospitals.

THE WAY FORWARD?

Though we should be striving towards patient-centred care, we must accept that patient–doctor interactions are driven by forces of different kinds. Sometimes the doctor will take control with the patient's implicit consent; sometimes public health considerations weigh heavily. Whatever the circumstances the priority is high clinical quality, backed by regulatory systems. Much of patient-centred care is to do with communication with patients—a skill that can be taught, and now prominent in medical-student education. Those of us who finished formal training some years ago need to be self-critical and hone our skills. To become more effective in communicating the concept of risk is a particular challenge. For doctors also, patient-centred care demands humility, for if the patient is at the centre it follows that we must be at the periphery. Another big obstacle to implementation of patient-centred care is the present working of the National Health Service. There is too little time to treat patients as the most important part of the system. The emphasis is on throughput, not input, and this has the effect of putting quality of interaction second to quantity. More time per patient requires more healthcare workers on the ground, and the solution to that is political, not medical.

References

- 1.Coulter A. After Bristol: putting patients at the centre. BMJ 2002;324: 648-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry. Learning from Bristol: the Report of the Public Inquiry into Children's Heart Surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995. London: Stationery Office, 2001. [www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk]

- 3.Balint M. The Doctor, his Patient and the Illness. London: Tavistock Publications, 1957

- 4.Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P. The Consultation: an Approach to Teaching and Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984

- 5.Smith R. The discomfort of patient power [Editorial]. BMJ 2002;324: 497-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orth JE, Stiles WB, Sherwitz L, et al. Patient exposition and provider explanation in routine interviews and hypertensive patients' blood pressure control. Health Psychol 1987;6: 29-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Headache Study Group of University of Western Ontario. Predictors of outcome in headache patients presenting to family physicians—a one year prospective study. Headache J 1986;26: 285-94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of patient centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current wellbeing and future disease risk. The Diabetes Care from Diagnosis Research Team. BMJ 1998;317: 1202-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennelly C, Bowling A. Suffering in deference: a focus group study of older cardiac patients' preferences for treatment and perceptions of risk. Qual Health Care 2001;10(suppl 1): 123-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kmietowicz Z. Government launches intensive media campaign on MMR. BMJ 2002;324: 383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staessen JA, Gasowski J, Wang JG, et al. Risks of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet 2000;355: 865-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashworth J. Science, Policy and Risk. London: Royal Society, 1997

- 13.Stamler J, Wentworth D, Neaton JD for the MRFIT research group. Relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease: continuous and graded. Findings in 356 222 primary cases of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). JAMA 1986;256: 2823-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickering WG. Clinical quality should be put at the centre of care [Letter]. BMJ 2002;324: 1398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gask L, Usherwood T. ABC of psychological medicine: the consultation. BMJ 2002;324: 1567-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]