Abstract

Immunosuppression in elderly recipients has been underappreciated in clinical trials. Here, we assessed age-specific effects of the calcineurin inhibitor Tacrolimus (TAC) in a murine transplant model and assessed its clinical relevance on human T-cells.

Old recipient mice exhibited prolonged skin graft survival when compared to young animals following TAC administration. More importantly, half of the TAC dose was sufficient in old mice to achieve comparable systemic trough levels. TAC administration was able to reduce pro-inflammatory IFN-γ cytokine production and promote IL-10 production in old CD4+ T-cells. In addition, TAC administration decreased IL-2 secretion in old CD4+ T-cells more effectively while inhibiting the proliferation of CD4+ T-cells in old mice. Both, TAC treated murine and human CD4+ T-cells demonstrated an age-specific suppression of intracellular calcineurin levels and Ca2+-influx, two critical pathways in T-cell activation. Of note, depletion of CD8+ T-cells did not alter allograft survival outcome in old TAC treated mice, suggesting that TAC age-specific effects were mainly CD4+ T-cell mediated.

Collectively, our study demonstrates age-specific immunosuppressive capacities of TAC that are CD4+ T-cell mediated. The suppression of calcineurin levels and Ca2+-influx in both, old murine and human T-cells emphasizes on the clinical relevance of age-specific effects when utilizing TAC.

Introduction

Demographic changes and improved longevity have given rise to a growing elderly patient population receiving or awaiting organ transplants.(1) The incidence of irreversible end organ damage in older patients has markedly increased during the last decades and the majority of transplant recipients and organ donors is currently older than 50 years.(2) While benefits of organ transplantation in older patients have been established, there is a higher risk for infections, cardiovascular diseases or malignancies, all exacerbated by immunosuppressive therapies.(3,4) Clinical trials have mostly excluded older transplant recipients and relevant aspects of immunosuppression have thus not been addressed sufficiently. Indeed, a meta-analysis of more than 500 studies revealed that trial participants who underwent kidney transplantation were significantly younger than the overall kidney transplant recipients in the US.(5) Moreover, recognizing the necessity to respond to the rapid demographic shift, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently encouraged clinical trials in the elderly (6) to explore age-specific aspects of immunosuppressants.

Although functional implications of immunosenescence have been explored extensively, age-specific effects of TAC in organ transplantation remain unclear.(7) With aging, phenotypic and functional changes such as an increase in the number CD4+ T cells that lack CD28 surface expression lead to compromised responses of T cells to antigens linked to impaired interaction between T cell receptor and antigen.(8,9) Consequently, old T cells are only partially activated or remain in an anergic state.(10) Overall, lower rates of naïve T cells along with a shift towards memory and effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations are characteristic in aging.(11,12) Clinically, we have previously shown that older recipients have reduced frequencies of acute rejections in parallel to an augmented susceptibility to immunosuppressants.(13)

Age-specific pharmacokinetic aspects of Tacrolimus have been explored recently. A prospective clinical trial has shown that kidney transplant recipients older than 65 years required only half of a body weight adjusted dosage to achieve therapeutic trough levels(14). Those age-dependent trough levels may be explained by an augmented first-pass metabolism of TAC linked to a decline of hepatic cytochrome P450 by approximately 8% with every decade of life.(15)

Here, we addressed age-specific aspects of TAC in a fully MHC mismatched skin transplantation model and confirmed the clinical relevance of our findings in human T cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type DBA/2 (H2d; 8–12 weeks) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA USA). Young (male, 8–12 weeks) and old (male, 18 month) mice C57BL/6 (H2b) were obtained from the National Institute of Aging (NIA, Bethesda, MD, USA). All animals were housed for three weeks in our facility prior to experiments; animals were allowed free access to water and standard chow. Experiments were approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee for Research on Animals. Use and care of animals were in accordance with National Institutes of Health and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Skin transplantation

Fully mismatched skin transplantations were performed; in detail, full-thickness skin grafts (1cm2) were removed from the tail of young DBA/2 mice and engrafted onto the dorsolateral thoracic wall of young and old C57BL/6 mice. Graft rejection was defined as necrosis exceeding 90%.

Tacrolimus (FK506)

TAC (Invivogen, CA, USA) was dissolved in Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and diluted with PBS. TAC was administered intraperitoneally every 12 hrs; TAC trough levels were measured by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was estimated by a trapezoidal rule applying the arithmetic means at each time point of the elimination phase (by 1, 4, 8, and 12 hrs) with as the time point of administration, k denoting sampling times, representing the mean of the sample response and Δtj = (tj + s − tj):

| (16) |

Isolation of murine cells

Single cell suspensions were obtained from spleens and CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) using biotinylated antibodies directed against non-CD4+ T cells (CD8, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, CD24, CD45R/B220, CD49b, TCRγ/δ, TER119). Cells were used at a purity > 95%.

Isolation of human cells

Whole blood (WB) lysis samples were prepared with ACK lysing buffer (Lonza, NJ, USA). CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) using biotinylated antibodies directed against non-CD4+ T cells (CD8, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD25, CD36, CD56, CD61, CD66b, CD123, HLA-DR, TCRγ/δ, glycophorin A, and CD45RO+). Cells were used at a purity > 95%.

Cell culture

CD4+CD44−CD62L+ T cells from splenocytes of young or old C57BL/6 mice were cell-sorted from CD4+ T cells isolated by negative selection. To explore the clinical relevance, healthy young (age<30; n=5) and old (age>75; n=5) human donors provided blood samples after giving informed consent, as participants in protocols approved by the local Institutional Review Board at the Charite Berlin, Germany. Naïve CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO−CCR7+CD62L+ T cells were isolated from blood samples.

Isolated CD4+ T cells or splenocytes were cultured in 24 well plates (0.5 × 106 cells per well) suspended with 0.8ml of RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 200mM L-glutamine, 100U ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin and 5 × 10−5 M β2-mercaptoethanol at 37°C under 5% CO2 and 95% air atmosphere with saturated humidity. CD4+ T cells were cultured in coated wells with 10 μg ml−1 anti-mouse α-CD3 and 2 μg ml−1 soluble anti-mouse α-CD28 (both eBioscience, CA, USA). Splenocytes were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS. TAC was dissolved in DMSO and diluted in PBS.

To determine absolute numbers of viable lymphocytes, Trypan staining was performed and live cells were counted using a hemocytometer (850 FS, Drew Scientific, TX, USA). In addition, flow cytometry was used with an a-priori defined sample flow rate and sample volume to assess absolute numbers of T cell subtypes.

Th1-polarizing conditions

Naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured in Th1-polarizing conditions for 96 hrs. The following antibodies were used for murine cells: 50ng ml−1 recombinant mouse IL-2, 50ng ml−1 recombinant mouse IL-12 and 10 μg ml−1 anti-mouse IL-4 (all eBioscience, CA, USA); for human cells we used: 50ng ml−1 recombinant human IL-2, 50ng ml−1 recombinant human IL-12 and 10 μg ml−1 anti-human IL-4 (all eBioscience, CA, USA). As controls, naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured with recombinant mouse IL-2 (50ng ml−1) to maintain T cell survival. After 96 hrs, supernatant and murine cells were analyzed by ELISA and flow cytometry, respectively. After 12 days, supernatant and human cells were analyzed by ELISA and flow cytometry, respectively.

T cell proliferation

The proliferation of CD4+ T cells was determined by CFSE (eBioscience, CA, USA). Briefly, CFSE was dissolved in DMSO to a final stock solution of 10mM and then re-suspended to 106 cells/ml at a concentration of 1 μM. Cells were incubated for 10 min. at room temperature, then for 5 minutes at 4°C and plated subsequently. Fluorescence of CFSE stained cells was assessed by flow cytometry with a peak excitation of 494 nm and peak emission of 521 nm (FACS Canto II, BD).

Flow cytometry

Cells were labeled with fluorescence antibodies for mouse α-CD4, α-CD8, α-INF-γ, α-IL-2, α-IL-10, α-IL-4, α-IL-17A, α-CD44, and α-CD62L (eBioscience, CA). To assess immune responses after transplantation, total splenocytes or isolated CD4+ T cells were seeded on 48 well plates and stimulated in complete media for 4 hrs at 37°C with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 50 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), Ionomycin (500ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and Brefeldin A (eBioscience). Thereafter, cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with respective antibodies at a concentration of 1–5 μg per 106 cells. Flow cytometry measurements were performed on a FACS Canto II (BD Bioscience, CA, USA) and data were analyzed using FlowJo (FlowJo Software, OR, USA).

ELISA

Th1 (IL-2 and INF-γ), Th2 (IL-10 and IL-4) and Th17 (IL-17) specific cytokines were measured using commercial ELISA kits (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ELISpot

Splenocytes were obtained from young and old C57BL/6 mice 7 days after transplantation and subsequently cultured in the presence of naïve splenocytes from DBA/2 (H2d) for 48 hrs. Elispot testing was performed as described previously.(17) Spots were determined by a computer-assisted enzyme-linked Immunospot image analyzer (Cellular Technology, Cleveland, OH, USA).

Calcineurin and Calcium Assay

For calcium measurements, naïve CD4+ T cells from young and old mice were cultured under Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3/α-CD28 for 96 hrs. Cells were dyed with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator (Fluo-4 NW calcium Assay kit, Molecular Probes, OR, USA) and stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin together with the protein transport inhibitor Brefeldin A (Biolegend, CA, USA). Cells were then incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and subsequently for an additional 30 min at room temperature and quantified by fluorescence reader at 494 nm and 516 nm (Spectramax, Molecular devices, USA). The concentration of calcineurin was measured by an enzyme immunoassay according to manufacturer’s instructions (Cloud-Clone Corporation, Houston, USA).

Naïve CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO−CCR7+CD62L+ human T cells from both, young (age<30; n=5) and old (age>75; n=5) healthy volunteers were cultured under Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3/α-CD28 with or without TAC (5 ng/ml). Intracellular concentrations of calcineurin were measured after 96hrs using a cellular calcineurin phosphatase activity assay (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Ca2+ influx into naïve human CD4+ T cells was measured using a fluorescent Ca2+ calcium indicator after cultivating human CD4+ T cells under Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3/α-CD28 with or without TAC (Fluo-4 NW calcium Assay kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After 96hrs, cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and for an additional 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin and Brefeldin A (Biolegend, CA, USA) and subsequently analyzed at 495 nm and 520 nm.

CD8+ T cell depletion

Young and old C57BL/6 skin transplant recipients received intravenous (tail vein) administration of 100μg anti-mouse α-CD8 monoclonal purified antibody (Clone 53–6.7; Biolegend, CA, USA) every other day starting at the day of transplantation. Treatment resulted in reliable depletion of > 90% of CD8+ T cells in recipient mice (Fig. 8).

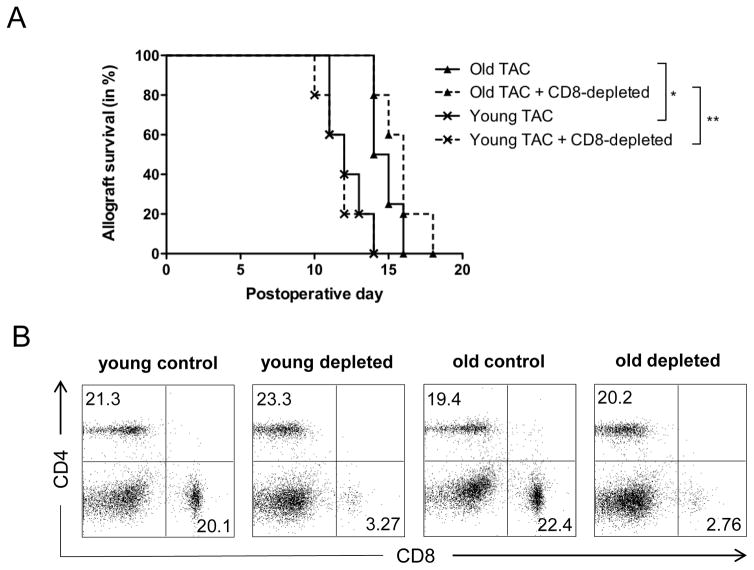

Figure 8. Prolonged graft survival in old recipient animals following TAC administration is not mediated by CD8+ T cells.

Skin allografts from young DBA mice were transplanted onto young and old C57BL/6 mice and treated with trough level adjusted TAC levels (young mice received 0.5mg/kg TAC and old mice 0.25mg/kg TAC). Mice received either α-CD8 (100μl in 1ml) or carrier solution (PBS, 1ml) intraperitoneally every other day after transplantation and graft survival was monitored (A). After 7 days, splenocytes were collected and frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were measured using flow cytometry (B). Representative plots of n=5 per group are shown. Statistics: *p<0.05; **p<0.01. Log-rank test was used to compare graft survival.

Statistics

Differences between groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. Graft survival was compared by Log-rank test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Results

TAC treated old recipient mice exhibit prolonged graft survival

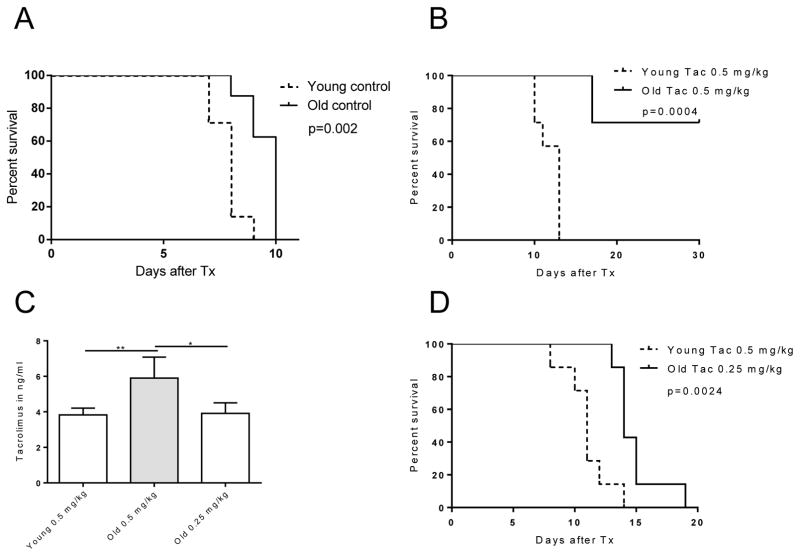

To explore the efficacy of TAC in immunosenescence and to examine age-dependent rejection rates, skin grafts from young DBA/2 (H2d) mice were transplanted onto young and old C57BL/6 (H2b) mice. Consistent with our previous experimental work (18), older, untreated recipients exhibited a prolonged graft survival when compared to young animals (Fig. 1A). Of particular relevance, when old and young recipients received weight-adapted doses of TAC, the majority of older recipients survived until the end of the observation period (day 30) while young animals rejected allografts by day 11 (mean survival time; n=7; p<0.0004; Fig. 1B). Of note, weight-dosed TAC resulted into significantly elevated trough levels in old recipients (Fig. 1C). With therapeutic TAC levels, achieved when applying only 50% of a weight-adapted dose in older recipients (0.25 mg/kg compared to 0.5 mg/kg in young mice (Fig. S1), old mice retained their skin grafts significantly longer, however prolongation of graft survival was less pronounced (p= 0.0024; Fig. 1D). Collectively, these results suggested that TAC enhances allograft survival in an age-specific manner.

Figure 1. Graft survival in young and old recipients.

Skin allografts from young DBA mice were transplanted onto young and old C57BL/6 mice (n=7 per group). Recipients remained either (A) untreated, (B) received weight-adjusted TAC, or (C) trough level adjusted TAC. (D) Old recipients required only half of the weight-adapted dose (n=5 per group) to reach comparable, age-matched trough levels. Graft survival was significantly prolonged in old recipients receiving weight-adjusted TAC doses. Age-differences in graft survival remained, albeit less pronounced, when TAC was applied based on trough levels. Statistics: mean±SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.01. Log-rank test was used to compare graft survival; Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups.

TAC enhances immunosuppressive responses in old CD4+ T cells

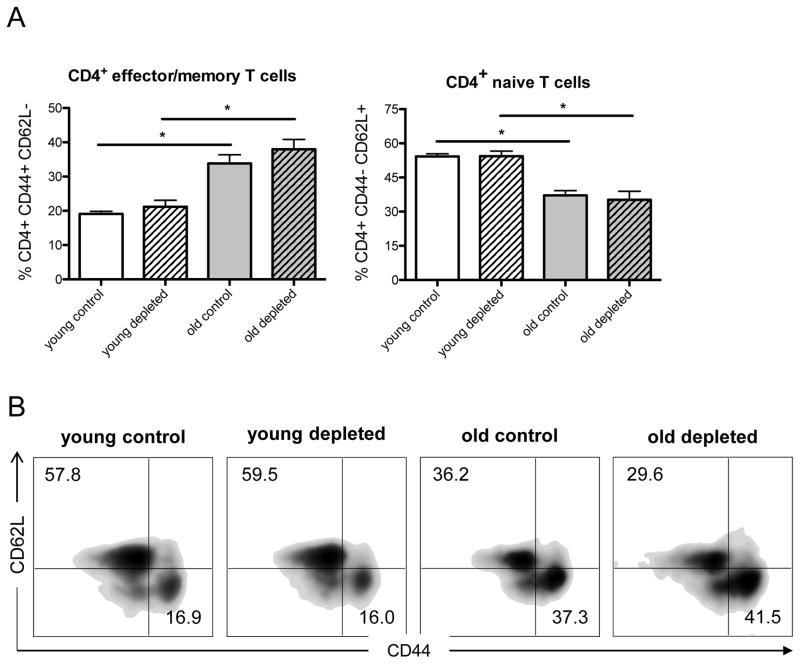

CD4+ T cells constitute a major subset that plays a critical role in alloimmune responses and allograft rejection.(19,20) We have previously shown that aging alters frequencies of CD4+ T cell populations. In line with other groups, we found that aging is associated with a decline in naïve and increased frequencies of effector/memory CD4+ T cells both, in clinical and experimental models.(17,18,21) Thus, we assessed in-vivo, whether TAC administration altered CD4+ T cell populations. Following skin transplantation and TAC treatment, old mice exhibited higher frequencies of CD4+CD44highCD62Llow effector/memory T cells while frequencies of naïve CD4+CD44lowCD62Lhigh T cells declined (Fig. 2). Of note, those age-specific effects were not impacted when CD8+ T-cells had been depleted. Taken together, our results suggest that TAC promotes allograft survival in old mice without targeting effector/memory CD4+ T cell populations.

Figure 2. TAC does not alter CD4+ T cell subpopulations.

Skin allografts from young DBA mice were transplanted onto young and old C57BL/6 mice (n=5 per group) and treated with trough level adjusted TAC levels (young mice received 0.5mg/kg TAC and old mice 0.25mg/kg TAC). Mice received either α-CD8 (100μl in 1ml) or carrier solution (PBS, 1ml) intraperitoneally every other day after transplantation. After 7 days, splenocytes were collected and frequencies of CD4+CD44highCD62Llow effector/memory T cells and CD4+CD44lowCD62Lhigh naïve T cells were measured by flow cytometry (A). Representative FACS plots for each group are given (B). Statistics: n 5; mean±SD; *p<0.05; *p<0.001. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups.

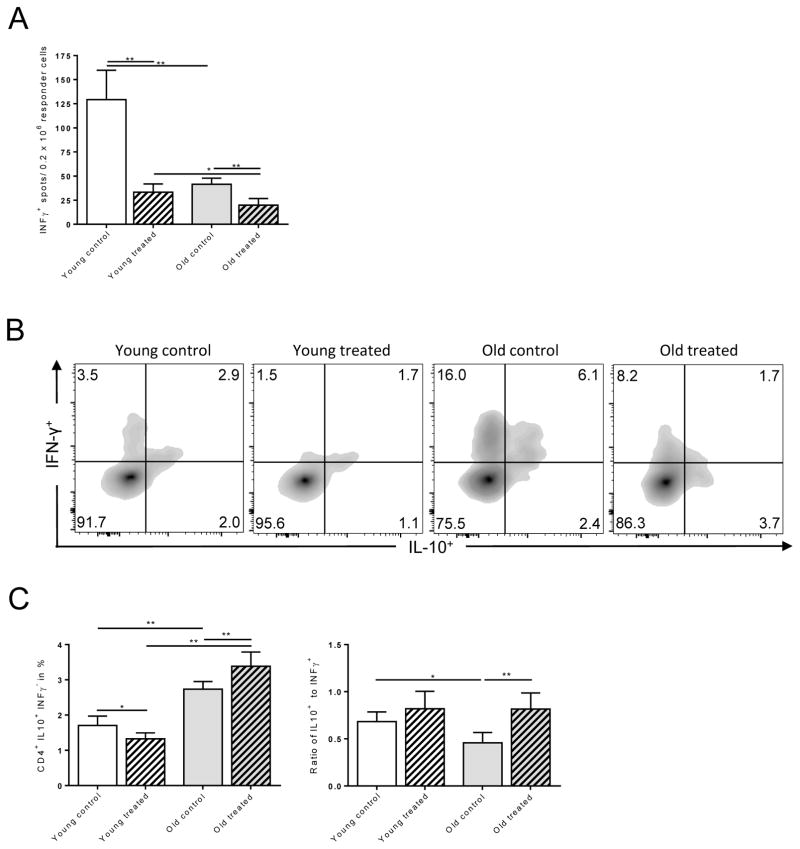

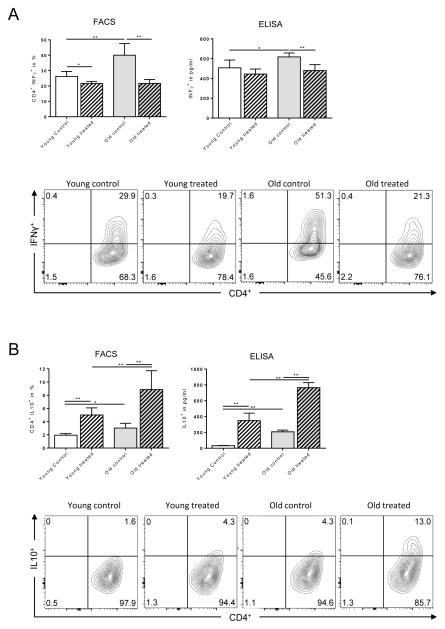

It is well established that CD4+ T cell differentiation and cytokine profiles play a critical role in regulating immune responses.(22) Indeed, IFN-γ is critical in augmenting alloimmune responses and allograft rejection while IL-10 has been linked to less vigorous alloimmunity and prolonged allograft survival.(23) More importantly, IFN-γ producing cells that co-express IL-10 have displayed immunosuppressive properties.(24) We therefore focused on the effects of TAC on old CD4+ T cells and tested whether the observed prolongation of graft survival in old mice was linked to a modified balance of IFN-γ and IL-10 production by CD4+ T cells. Old and young mice underwent fully MHC-mismatched skin transplants and systemic IFN-γ and IL-10 production was quantified by flow cytometry. ELISpot analysis indicated a dramatic decrease in IFN-γ production in both, young and old animals following TAC administration (Fig. 3A). More importantly, flow cytometry analysis indicated that frequencies and ratios of CD4+ IL-10+ IFN-γ− cells were significantly elevated in old, TAC treated animals (Fig. 3B and 3C). The enhanced suppression of IFN-γ in old CD4+ T cells and decreased secretion of IL-10 in young CD4+ T cells subsequent to TAC treatment was also confirmed by ELISA (Fig. S2). Next, we assessed the role of TAC on T cell differentiation and the capacity of TAC to regulate IFN-γ and IL-10 production in-vitro. Consistent with our previous findings, IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells isolated from young and old animals exposed to Th1-polarizing conditions had been effectively suppressed by TAC (Fig. 4A). Moreover, frequencies of old CD4+ IL-10+ T cells increased dramatically when TAC had been added (Fig. 4B). Collectively, those data suggest that TAC exerts age-specific effects on IFN-γ and IL-10 cytokine production that promote immunosuppressive responses in old CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3. Th1-specific effects of TAC in old mice.

Splenocytes (0.5 × 106) from young and old C57BL/6 recipients were co-cultured with anergic, mitomycin-treated DBA/2 splenocytes (A). After 48 hrs, frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells were measured by ELISpot. Skin allografts from young DBA mice were transplanted onto young and old C57BL/6 mice (young mice received 0.5mg/kg TAC, old mice 0.25mg/kg TAC). By day 6, CD4+ T cells were isolated and stimulated for 4 hrs. CD4+ T cells were analyzed for IL-10 and IFN-γ production by flow cytometry (B, C). Statistics: n ≥ 5; mean±SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.001. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups.

Figure 4. Effects of TAC in Th1-polarizing conditions.

Naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured under Th1-polarizing conditions (50ng ml−1 recombinant mouse IL-2, 50ng ml−1 recombinant mouse IL-12 and 10 μg ml−1 anti-mouse Il-4; eBioscience, CA, USA). By 96 hrs, (A) IFN-γ and (B) IL-10 production were measured by flow cytometry and ELISA. Statistics: n ≥ 5; mean±SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.001. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups.

Age-dependent effects of Tacrolimus on IL-2 production and CD4+ T cell proliferation

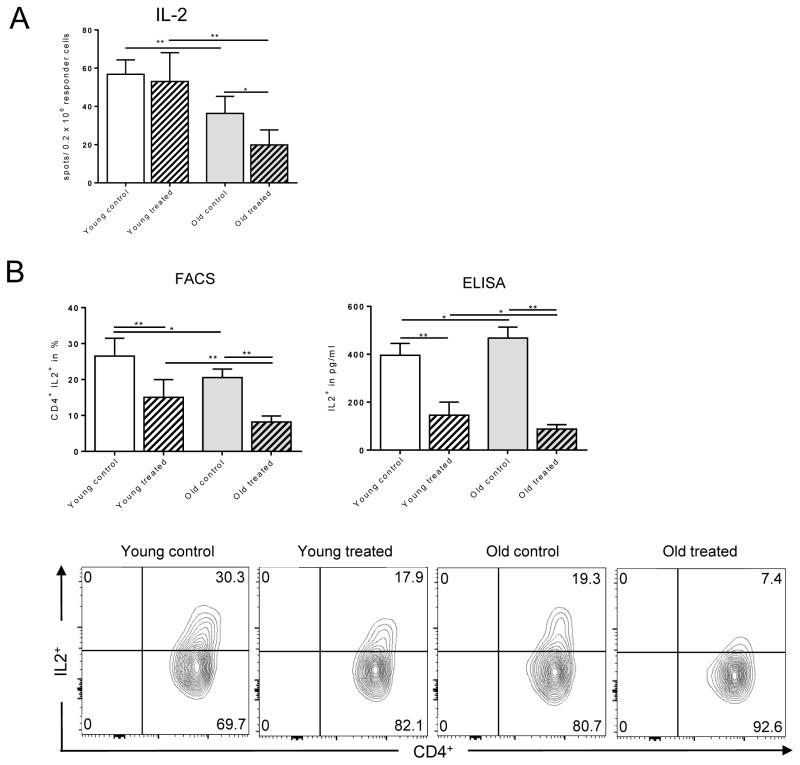

Previous studies have reported on age-specific changes of thymic output and repopulation of T cells linked to alterations of cytokine production.(25) Indeed, IL-2 has been shown to have an age-dependent expression that critically maintains CD4+ T cell activation and proliferation.(26) Therefore, we determined the systemic secretion of IL-2 that is known to maintain CD4+ T cell activation and proliferation. Total splenocytes isolated from untreated old animals exhibited a decline in IL-2 secretion that was enhanced by TAC in an age-specific fashion (Fig. 5A). To further dissect the impact of TAC on IL-2 production, we performed fully mismatched skin transplants in old and young animals and analyzed the production of IL-2 by CD4+ T cells. As shown in Fig. 5B, TAC inhibited IL-2 production in-vivo in an age-specific manner. Old animals treated with TAC demonstrated a compromised IL-2 secretion. Moreover, reduced IL-2 secretion was associated with a reduced proliferation of old CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3). Interestingly, inhibitory effects of TAC were significantly more pronounced in purified old CD4+ T cells suggesting compensatory effects in unseparated splenocytes (Fig. S3). Taken together, these results indicate that TAC inhibits CD4+ T cell proliferation and IL-2 secretion in an age-specific fashion.

Figure 5. More pronounced suppression of IL-2 in old CD4+ T cells subsequent to TAC treatment.

Splenocytes (0.5 × 106) from young and old C57BL/6 recipients of DBA/2 skin allografts were collected 6 days after transplantation; mice received trough level adjusted TAC (young mice received 0.5mg/kg TAC and old mice 0.25mg/kg TAC). Splenocytes were co-cultured with anergic DBA/2 splenocytes. By 48 hrs, IL-2 secretion was assessed by ELISpot (A). CD4+ T cells were isolated and stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin/Brefeldin A for 4 hrs. IL-2 secretion was measured by flow cytometry and ELISA (B). Statistics: n ≥5; mean±SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.001. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups.

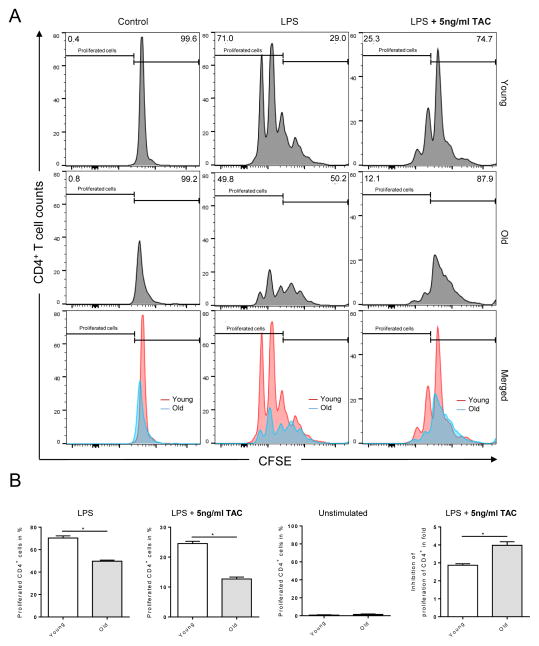

Figure 6. Impaired proliferation of old CD4+ T cells following TAC treatment.

Splenocytes (0.5 × 106) from young and old C57BL/6 recipients of DBA/2 skin allografts were collected 7 days after transplantation; mice received trough level adjusted TAC (young mice received 0.5mg/kg TAC and old mice 0.25mg/kg TAC). Afterwards, total splenocytes were cultured with (i) LPS (10ng/ml), (ii) LPS (10ng/ml) and treated with 5ng/ml TAC, or (iii) media alone and proliferation was determined by CFSE staining. After 72 hrs, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Statistics: n ≥ 5; mean±SD; *p<0.05. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups.

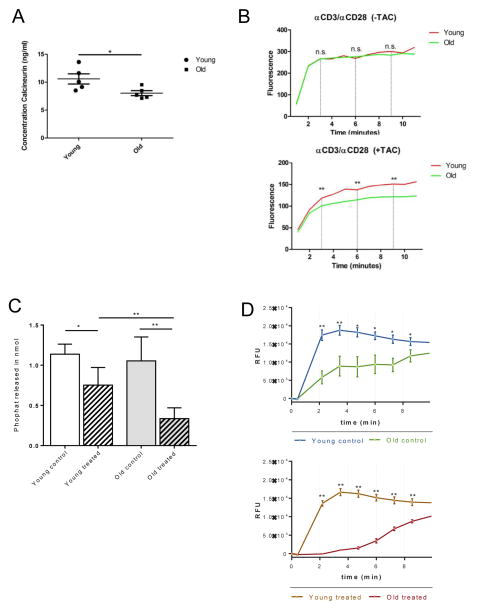

Age-dependent effects on Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent calcineurin activity by TAC

Next, we assessed Ca2+ influx and calcineurin levels, both known to play a central role in NFAT activation, a major downstream pathway of T cell receptor activation.(27) Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated from splenocytes of young and old mice and cultured under Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3/α-CD28. Our ELISA assay showed that intracellular concentrations of calcineurin were significantly reduced in old CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7A). Next, we quantified Ca2+ influx following T cell activation, as calcineurin is known to be activated by Ca2+. Although calcium influx was similar in young and old CD4+ T cells in absence of TAC treatment, addition of TAC to the culture resulted in a prominent suppression of Ca2+ influx in an age-specific fashion (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Intracellular concentrations of calcineurin and Ca2+ in young and old murine and human CD4+ T cells.

Isolated naïve CD4+ T cells from young and old mice were cultured in Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3/α-CD28. By 96 hrs, intracellular concentration of calcineurin was measured by sandwich ELISA (Cloud-Clone Corp., Houston, USA) (A). For measurement of Ca2+ influx, isolated naïve CD4+ T cells from young and old mice were cultured in Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3/α-CD28 for 96 hrs and treated with and without TAC (5ng/ml). Cells were dyed with a fluorescent Ca2+ calcium indicator (Fluo-4 NW calcium Assay kit, Molecular Probes, OR, USA) and then stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin including Brefeldin A (Biolegend, CA, USA) and subsequently analyzed with a fluorescence reader at 494 nm and 516 nm (B). In addition, isolated naïve CD4+ T cells from young (<30) and old (>75) volunteers were cultured under Th1-polarizing conditions, in presence of α-CD3 and α-CD28 with or without TAC (5ng/ml). By 96 hrs, the concentration of calcineurin was measured using a cellular calcineurin phosphatase activity assay (C). Next, isolated naïve young and old human CD4+ T cells were cultured under Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3 and α-CD28 for 96 hrs with or without TAC (5ng/ml) and dyed with a fluorescent Ca2+ calcium indicator (Fluo-4 NW calcium assay kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following incubation, cells were stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin and fluorescence was read at 495nm and 520nm (D). Statistics: n=5; mean±SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.01. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups.

TAC does not promote prolonged allograft survival in old recipients via CD8+ T cells

Although our data suggest that TAC alters CD4+ T cell differentiation and cytokine production, it is well established that CD8+ T cells play a critical role in alloimmune responses and graft rejection as well.(19) Indeed, CD8+ T cells have been shown to be able to mediate graft rejection in absence of CD4+ T cells.(28) Thus, we next investigated the role of TAC on CD8+ T cells and allograft survival by depleting CD8+ T cells in recipient animals. Intravenous administration of 100μg α-CD8 every other day depleted CD8+ T cells reliably (Fig. 8). While effects of TAC treatment on graft survival in young and old control groups were consistent with our initial experiments (Fig. 1), depletion of CD8+ T cells in TAC-treated young and old recipients did not alter age-specific differences in graft survival (Fig. 8). Taken together, these results suggest that prolonged graft survival in old recipient animals following TAC administration is not mediated by CD8+ T cells.

Calcineurin levels and Ca2+ influx are significantly reduced in old human CD4+ T cells

Our results indicated that TAC alters calcineurin levels and Ca2+ influx known to play a central role in T cell activation. Therefore we set out to explore the relevance of our findings in human CD-4+cells Here, we assessed naïve CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO− CCR7+CD62L+ T cells from young (age<30) and old healthy human volunteers (age>75) and cultured those cells under Th1-polarizing conditions and in presence of α-CD3/α-CD28. While calcineurin levels in control (PBS treated) groups were comparable, old human naïve CD4+ T cells treated with TAC revealed a significantly reduced concentration of calcineurin (Fig. 7C). Moreover, the addition of TAC to the culture resulted in a dramatically reduced influx of Ca2+ in old T cells (Fig. 7D). These experiments show that TAC regulates Ca2+ influx and calcineurin levels in both, murine and human CD4+ T cells in an age-specific manner, emphasizing the clinical relevance of our findings.

Discussion

It is well established that aging has broad effects on all immune compartments. Moreover, we and others have reported that immunosenescence impacts alloimmune responses following organ transplantation.(29,30) Although rejection rates are less frequent in older patients (13), little is known about age-specific aspects of established immunosuppressants. Yet, age-specific concepts of immunosuppression are of clinical significance as the majority of renal transplant recipients are older than 50 years.

In our current study, we were able to show that TAC favors allograft survival in old mice. Pharmacokinetic profiles in our model confirmed the clinical relevance of our model with old mice requiring only half of a weight-adapted dose to achieve therapeutic trough levels. These findings are in accordance with previous clinical observations in kidney transplant recipients (14) and strongly support an age-dependent reduction in first-pass effects and hepatic metabolism. Of note, when adjusting the AUC subsequent to therapeutic TAC trough levels, old mice still exhibited a prolonged, although less pronounced graft survival. To the best of our knowledge, this is a novel finding in the debate on age-specific immunosuppression.(29)

Moreover, TAC suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokine production more efficiently in old CD4+ T cells. Of relevance, decreased levels of IL-2 have been linked to an intensified control of NFATc1.(31) Specifically, TAC demonstrated enhanced capacities of suppressing IL-2 in old mice, thus showing anti-proliferative capacities on CD4+ T cells. While the critical role of IL-2 in T cell activation has been recognized, this effect appears impaired with age. Moreover, reduced CD-4 proliferation can be restored by exogenous IL-2 at comparable rates for young and old CD4+ T cells.(32) Strikingly, TAC was able to suppress old CD4+ IL-2+ T cells more effectively in an age-specific fashion.

It is known that calcineurin activity declines with aging, although these findings have not been associated with changes in calcineurin protein levels.(33,34) Nevertheless, our data indicate reduced concentrations of calcineurin not only in old murine but also in old human CD4+ T cells. Of note, when measuring cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations, we found no significant differences between young and old CD4+ T cells. However, when TAC was added in-vitro, we detected lower Ca2+ levels again both in old human and murine CD4+ T cells suggesting that aging may render Ca2+ channels more susceptible to TAC.

In line with an augmented suppression of IL-2 in old mice, anti-proliferative capacities of TAC were enhanced in old CD4+ T cells. Although TAC did not affect the composition of CD4+ T cell subpopulations, TAC inhibited cytokine production in an age-specific manner. In line with our previous studies (17,18), overall production of IFN-γ in splenocytes of old animals was significantly reduced compared to their young counterparts while frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were significantly elevated in old recipients. Although these findings may appear contradictive at a first glance, production of IFN-γ increased in parallel with an increased production of IL-10 in old animals. Of note, double-positive CD4+IFN-γ+IL-10+ cells also termed regulatory type 1 cells display potent immunosuppressive properties and are able to promote allograft survival independently of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells.(24) Thus, altering the critical balance of IFN-γ and IL-10 may play a pivotal role in mediating age-specific effects of Tacrolimus.(32,35)

CD8+ T cells are known to play a central role in alloimmune responses and graft rejection. In our transplant mouse model, CD8+ T cell depletion did not alter prolonged allograft survival in TAC treated old recipient, suggesting that TAC effects were not CD8+ T cell mediated.

Clearly, further mechanistic studies detailing the interaction of TAC with CD4+ T cells in immunosenescence are in need. Particularly intriguing are our observations of abnormal Ca2+/calcineurin pathways in both old human and murine CD4+ T cells. While our human studies need to be expanded, they clearly show the clinical relevance of our findings. Our current experimental series has focused on young and old recipients, omitting studies in a ‘middle age’ group. Of note, previous unpublished results by our group have indicated no differences in alloimmunity between 12 and 18 mth old mice (data not shown).

In summary, our results demonstrate an augmented immunosuppressive capacity of TAC based on age-specific calcineurin activities linked to compromised CD4+ T cell responses that result into a prolonged graft survival in old recipients. These results are of clinical relevance for an age-specific immunosuppression aiming to be effective while limiting side effects that are particularly prominent in the aging transplant population.(36)

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Tacrolimus concentrations in whole blood samples

Figure S2: Th1-specific effects of TAC in old mice

Figure S3: Impaired proliferation of isolated CD4+ T cells

Acknowledgments

S.G.T. was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1AG039449). F.K. (KR 4362/1-1), M.Q. (QU 420/1-1) and T.H. (HE 7457/1-1) were supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG). M.S. was supported by German National Academic Foundation and International Academy of Life Sciences. J.M.S. was supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation.

Abbreviations

- TAC

Tacrolimus

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.World Population Ageing 2013. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2013. ST/ESA/SER.A/348. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watt KDS, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, Heimbach JK, Sanchez W, Gores GJ. Long-term probability of and mortality from de novo malignancy after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:2010–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karim A, Farrugia D, Cheshire J, Mahboob S, Begaj I, Ray D, et al. Recipient age and risk for mortality after kidney transplantation in England. Transplantation. 2014;97:832–8. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000438026.03958.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blosser CD, Huverserian A, Bloom RD, Abt PD, Goral S, Thomasson A, et al. Age, exclusion criteria, and generalizability of randomized trials enrolling kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2011;91:858–63. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31820f42d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Government Accountability Office. Prescription Drugs: FDA Guidance and Regulations Related to Data on Elderly Persons in Clinical Drug Trials. 2007. GAO-07-47R. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinbokel T, Elkhal A, Liu G, Edtinger K, Tullius SG. Immunosenescence and organ transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2013;27:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G, Lustig A, Weng N-P. T cell aging: a review of the transcriptional changes determined from genome-wide analysis. Front Immunol. 2013;4:121. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warrington KJ, Vallejo AN, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. CD28 loss in senescent CD4+ T cells: reversal by interleukin-12 stimulation. Blood. 2003;101:3543–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moro-García MA, Alonso-Arias R, López-Larrea C. When Aging Reaches CD4+ T-Cells: Phenotypic and Functional Changes. Front Immunol. 2013;4:107. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saule P, Trauet J, Dutriez V, Lekeux V, Dessaint J-P, Labalette M. Accumulation of memory T cells from childhood to old age: central and effector memory cells in CD4(+) versus effector memory and terminally differentiated memory cells in CD8(+) compartment. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:274–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong MS, Dan JM, Choi J-Y, Kang I. Age-associated changes in the frequency of naïve, memory and effector CD8+ T cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:615–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tullius SG, Milford E. Kidney allocation and the aging immune response. N Engl J Med Massachusetts Medical Society. 2011;364:1369–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1103007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson PA, Schladt D, Oetting WS, Leduc R, Guan W, Matas AJ, et al. Lower calcineurin inhibitor doses in older compared to younger kidney transplant recipients yield similar troughs. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3326–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warrington JS, Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL. Age-related differences in CYP3A expression and activity in the rat liver, intestine, and kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:720–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagnon RC, Peterson JJ. Estimation of confidence intervals for area under the curve from destructively obtained pharmacokinetic data. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1998;26:87–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1023228925137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bedi DS, Krenzien F, Quante M, Uehara H, Edtinger K, Liu G, et al. Defective CD8 Signaling Pathways Delay Rejection in Older Recipients. Transplantation. 2016;100:69–79. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denecke C, Bedi DS, Ge X, Kim IK-E, Jurisch A, Weiland A, et al. Prolonged graft survival in older recipient mice is determined by impaired effector T-cell but intact regulatory T-cell responses. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benichou G, Valujskikh A, Heeger PS. Contributions of direct and indirect T cell alloreactivity during allograft rejection in mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:352–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger NR, Yin DP, Fathman CG. CD4+ but not CD8+ cells are essential for allorejection. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2013–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appay V, Sauce D. Naive T cells: the crux of cellular immune aging? Exp Gerontol. 2014;54:90–3. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tashiro H, Shinozaki K, Yahata H, Hayamizu K, Okimoto T, Tanji H, et al. Prolongation of liver allograft survival after interleukin-10 gene transduction 24–48 hours before donation. Transplantation. 2000;70:336–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200007270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elkhal A, Rodriguez Cetina Biefer H, Heinbokel T, Uehara H, Quante M, Seyda M, et al. NAD(+) regulates Treg cell fate and promotes allograft survival via a systemic IL-10 production that is CD4(+) CD25(+) Foxp3(+) T cells independent. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22325. doi: 10.1038/srep22325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taub DD, Longo DL. Insights into thymic aging and regeneration. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:72–93. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobbs MV, Ernst DN, Torbett BE, Glasebrook AL, Rehse MA, McQuitty DN, et al. Cell proliferation and cytokine production by CD4+ cells from old mice. J Cell Biochem. 1991;46:312–20. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240460406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanno Y, Vahedi G, Hirahara K, Singleton K, O’Shea JJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic control of T helper cell specification: molecular mechanisms underlying commitment and plasticity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:707–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halamay KE, Kirkman RL, Sun L, Yamada A, Fragoso RC, Shimizu K, et al. CD8 T cells are sufficient to mediate allorecognition and allograft rejection. Cell Immunol. 216:6–14. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krenzien F, ElKhal A, Quante M, Rodriguez Cetina Biefer H, Hirofumi U, Gabardi S, et al. A Rationale for Age-Adapted Immunosuppression in Organ Transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99:2258–68. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frei U, Noeldeke J, Machold-Fabrizii V, Arbogast H, Margreiter R, Fricke L, et al. Prospective age-matching in elderly kidney transplant recipients--a 5-year analysis of the Eurotransplant Senior Program. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:50–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whisler RL, Beiqing L, Chen M. Age-related decreases in IL-2 production by human T cells are associated with impaired activation of nuclear transcriptional factors AP-1 and NF-AT. Cell Immunol. 1996;169:185–95. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haynes L, Linton PJ, Eaton SM, Tonkonogy SL, Swain SL. Interleukin 2, but not other common gamma chain-binding cytokines, can reverse the defect in generation of CD4 effector T cells from naive T cells of aged mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1013–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller RA. Calcium signals in T lymphocytes from old mice. Life Sci. 1996;59:469–75. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pahlavani MA, Vargas DM. Age-related decline in activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin and kinase CaMK-IV in rat T cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;112:59–74. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(99)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Swain SL. The defects in effector generation associated with aging can be reversed by addition of IL-2 but not other related gamma(c)-receptor binding cytokines. Vaccine. 2000;18:1649–53. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Issa N, Kukla A, Ibrahim HN. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity: a review and perspective of the evidence. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37:602–12. doi: 10.1159/000351648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Tacrolimus concentrations in whole blood samples

Figure S2: Th1-specific effects of TAC in old mice

Figure S3: Impaired proliferation of isolated CD4+ T cells