Abstract

Objective

To explore the development of family medicine postgraduate training in countries with varying levels of resources at different stages of development of the discipline.

Composition of the committee

Since 2012, the College of Family Physicians of Canada has hosted the Besrour Conferences to reflect on its role in advancing the discipline of family medicine globally. The Besrour Narrative Working Group was conceived in 2012 at the first Besrour Conference. Their mandate was to use narrative and appreciative inquiry to gather stories of family medicine worldwide. The working group comprised members of various academic departments of family medicine in Canada and abroad who attended the conferences.

Methods

A consultation process with our partners from lower-middle–income countries was undertaken from 2012 to 2014. Stories were sought from each global partner institute with ties to Canadian family medicine departments. An appreciative inquiry approach was chosen to elicit narratives. Thematic analysis was used to search for common threads and important elements of success that could serve to inform other initiatives in other nations and, in turn, offer hope for greater effect.

Report

Sixteen narrative stories have been collected so far. These stories highlight insightful solutions, foresight, perseverance, and ultimately a steadfast belief that family medicine will improve the health system and the care provided to the citizens of each nation. Seventeen themes were elucidated by 3 independent Canadian readers. At a subsequent workshop, these themes were validated by Besrour Centre members from Canada and elsewhere. The linkage between the thematic analysis and the experiences of various schools helps to illustrate both the robustness and the usefulness of the narratives in exploring generalizable observations and the features supporting success in each institute.

Conclusion

If we are to understand, and contribute to, the development of family medicine throughout the world (a key objective of the Besrour Centre), we must begin to hear each others’ stories and search for ways in which our collective story can advance the discipline.

Résumé

Objectif

Explorer l’évolution de la formation postdoctorale en médecine familiale dans des pays dont les niveaux de ressources varient et où la discipline en est à des étapes différentes de son développement.

Composition du comité

Depuis 2012, le Collège des médecins de famille du Canada organise les Conférences Besrour dans le but de réfléchir à son rôle dans l’avancement de la discipline de la médecine familiale à l’échelle mondiale. Le Groupe de travail sur les récits narratifs Besrour a été formé en 2012, à l’occasion de la première Conférence Besrour. Il a reçu pour mandat d’utiliser les récits narratifs et l’investigation appréciative pour recueillir des histoires de la médecine familiale venant de tous les coins du monde. Le groupe de travail comptait des membres de divers départements universitaires de médecine familiale au Canada et à l’étranger qui ont participé aux conférences.

Méthodes

Un processus de consultation avec nos partenaires venant de pays à faible et moyen revenu s’est déroulé de 2012 à 2014. Des récits ont été sollicités de chaque établissement partenaire dans le monde qui entretenait des liens avec les départements canadiens de médecine familiale. Une approche reposant sur l’investigation appréciative a été choisie pour susciter la rédaction des récits narratifs. L’analyse thématique a servi dans la recherche des dénominateurs communs et des éléments de réussite importants, susceptibles d’éclairer d’autres initiatives ailleurs dans le monde et, en retour, de permettre d’espérer ainsi une plus grande influence.

Rapport

Jusqu’à présent, 16 récits narratifs ont été reçus. Ces récits mettent en évidence des solutions judicieuses, de la clairvoyance, de la persévérance et, en définitive, une ferme conviction que la médecine familiale améliorera le système de santé et les soins dispensés aux citoyens de chaque pays. Trois lecteurs canadiens indépendants ont cerné 17 thèmes. À l’occasion d’un atelier subséquent, ces thèmes ont été validés par des membres du Centre Besrour du Canada et d’ailleurs. Les liens établis entre l’analyse thématique et les expériences des diverses facultés aident à illustrer tant la robustesse que l’utilité des récits narratifs dans l’exploration de constatations et de caractéristiques généralisables à l’appui de la réussite dans chaque établissement.

Conclusion

Si nous voulons comprendre le développement de la médecine familiale dans le monde et y contribuer (un objectif clé du Centre Besrour), nous devons commencer par écouter réciproquement nos récits et trouver des façons dont notre histoire collective peut faire avancer la discipline.

Ceux qui lisent ou écoutent nos récits voient tout comme à travers une lentille. Cette lentille est le secret de la narration et son focus se précise dans chaque récit, s’ajuste entre le temporel et l’infini. Si nous sommes, nous les raconteurs, les Secrétaires de la mort, nous le sommes parce que, dans notre brève vie de mortels, nous sommes les ajusteurs de ces lentilles.

John Berger, And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos (traduction libre)

Those who read or listen to our stories see everything as through a lens. This lens is the secret of narration, and it is ground anew in every story, ground between the temporal and the timeless. If we storytellers are Death’s Secretaries, we are so because, in our brief mortal lives, we are grinders of those lenses.

John Berger, And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos

The narrative project of the Besrour Centre was inspired by a remarkable initiative. While a group within the College of Family Physicians of Canada was examining family medicine activities worldwide, a consultation process with our partners from lower-middle–income countries (LMICs) was undertaken from 2012 to 2014.1 The presence of Canadian universities with LMIC collaborative partners offered a unique opportunity for us to learn from each other. If we are to understand, and contribute to, the development of family medicine throughout the world (a key objective of the Besrour Centre), we must begin to hear each others’ stories and search for ways in which our collective story can advance the discipline.

These narratives provide stories of success, perseverance, and inspiration to family doctors and academic leaders in promoting the discipline. The use of narrative as a research method is growing within family medicine, and its value is increasingly recognized:

The effective practice of medicine requires narrative competence, that is, the ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others .... Narrative competence ... enables the physician to practice medicine with empathy, reflection, professionalism, and trustworthiness.2

Much research has been done on the value of a patient’s narrative in strengthening the doctor-patient partnership. In a different but meaningful way, the narratives of our LMIC partners, who are the visionaries and pioneers of family medicine in their own countries, provide insight into this contextually shaped process of development. Narratives reveal the practical actions and the passions that drive us forward as well as provide an opportunity for a reflective accounting of our own story.

An appreciative inquiry approach was chosen to elicit narratives from partners throughout the world. Appreciative inquiry3–5 is an approach to analysis based on the assumption that in any complex undertaking something is working well—even if, at a superficial level, the system or organization seems to be failing. In innovative undertakings, such as the introduction of family medicine in low-resource health systems focused on specialist paradigms, difficulties and challenges are obvious. Traditional approaches, such as SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, tend to focus their attention on what is failing and why. “Barriers to change” becomes a common refrain, with long lists of suggestions that quickly transform themselves into excuses for continuing failure. Appreciative inquiry, on the other hand, seeks to explore complex systems to find functional subsystems and then analyze the factors that led to their success— the roots of their success. The analysis of these factors can then be used to create success in other parts of the system and, ultimately, in the system as a whole. While initially developed in the context of adaptive change in large corporations such as General Electric, it is an approach that has been validated and found to be effective in a range of applications, including by the authors of this paper. Far from denying the existence of problems and barriers, appreciative inquiry approaches them with consideration of the reasons for whatever success exists. This understanding leads to momentum for positive change rather than to the litany of excuses for failure that is the usual outcome of SWOT analysis. We have discovered through multiple similar processes that once people begin to discuss difficulties, the conversation becomes bogged down in inertia and pessimism. Analysis of narrative descriptions of complex issues is an established method for exploring the overall integrated nature of an issue before analyzing the interaction of its parts. Isolated analysis of the parts themselves frequently results in reductionist confusion or destruction of real meaning. Addressing the interactions of the parts within the context of the whole is challenging but more fruitful, just as having an overview of the landscape enhances your vision of the trails it might contain. One of the seminal thinkers in complexity theory, Nobel Laureate Murray Gell-Mann, describes the importance of “having a first crude look at the whole.”6 Thus, a guided narrative method was undertaken, using open-ended questions. It became evident during the consultative process that each LMIC partner had an important story to share. Challenges they faced were often also faced within Canadian and other international institutions. Moreover, stories of success could lend themselves to thematic analysis and contribute to advocacy for family medicine worldwide.

Listening to patients’ stories is at the heart of family practice, and this method was incorporated into the Besrour narrative project by listening to the stories of those who are building the profession globally.

Composition of the committee

Since 2012, the CFPC has hosted the Besrour Conferences to reflect on its role in advancing the discipline of family medicine globally. The Besrour Narrative Working Group was conceived in 2012 at the first Besrour Conference. Their mandate was to use narrative and appreciative inquiry to gather stories of family medicine worldwide. The working group comprised members of various academic departments of family medicine in Canada and abroad who attended the conferences.

Methods

The project was conceived at the first Besrour collaborative conference in 2012 and narratives have been collected since then. The team included 3 project leads from western Canada, with participation of others across the country. Many university partners contributed through a variety of discussions and opportunities for input. This project was developed and expanded during subsequent consultative meetings, with crucial input from Innocent Besigye (Uganda), Katrina Butterworth (Nepal), Andy Shillingford (the Caribbean), Kerling Israel (Haiti), Brian Cornelson (Ethiopia and Canada), and Vincent Cubaka (Rwanda). Stories were sought from each global partner institute with ties to Canadian family medicine departments.

The group sought to explore the development of family medicine postgraduate training in countries with varying levels of resources at different stages of development of the specialty. Given the unique circumstances in each country, it was apparent that the project could quickly accumulate an unmanageable amount of data. The task was approached by gathering narrative descriptions using the appreciative inquiry approach.

To collect stories from such a diverse group of family medicine leaders and primary care stakeholders, a flexible process was designed. Three questions were asked within a template, but the respondents had full opportunity to focus their answers on what they believed were key elements in the success of their programs or departments. The template requested the following:

a brief description of the country and the health of its people (especially as it pertains to equity in health and access);

the context in which family medicine was proposed and developed; and

a description of one thing (policy, tool, concept, or strategy) that is working very well in the environment, and why the respondent thinks it is succeeding.

As the overall Besrour process advanced, additional narratives were gathered. The flexibility of the process allowed the emergence of a rich variety of narratives with a large but manageable number of participant observations about the development of family practice in various contexts.

Narratives were gathered using partners’ own language whenever possible; however, translation was provided by the Canadian partner. Narratives were gathered in both French and English and were cross-translated on the site.

This provided an opportunity to undertake thematic analysis to search for common threads and important elements of success that could serve to inform other initiatives in other nations and, in turn, offer hope for greater effect. The collected narratives were reviewed independently by 3 external readers (C.G., R.W., and V.K.). Themes were identified through member checking.7 Themes identified in more than 1 or 2 schools were judged to be more robust than those noted in single countries. The lists were then reviewed in a consensus process wherein the 3 reviewers agreed on nomenclature and the validity of each theme on its own. This list formed the basis for going back to each of the country reports to see which themes were expressed.

As further narratives were received, further member checking determined when no new themes were identified. The resulting list of themes was then presented to a workshop of 20 participants and representatives from around the world, and the group was challenged to reflect on whether additional themes should be included. The workshop validated the importance and completeness of the list of identified themes. It thus provided the backdrop upon which more detailed and verified narratives could be analyzed and upon which a useful picture of the development of family practice could emerge.

Report

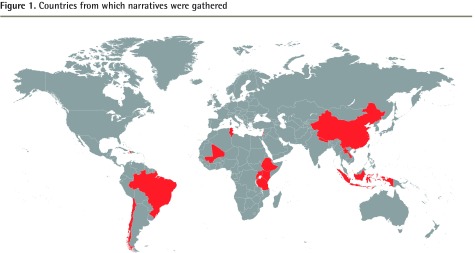

Sixteen narrative stories have been collected so far from partners of Canadian universities (Figure 1). These stories highlight insightful solutions, foresight, perseverance, and ultimately a steadfast belief that family medicine will improve the health system and the care provided to the citizens of each nation. It has been an inspiring journey collecting these stories. Many remarkable stories of endurance through challenges emerged and have proven inspirational to the Canadian partners and other family physicians worldwide. They have been summarized on the website of the College of Family Physicians of Canada (http://global.cfpc.ca).

Figure 1.

Countries from which narratives were gathered

Thematic analysis.

Themes inferred are presented in Box 1. There were 17 themes elucidated by the 3 independent Canadian readers in the process described above. At the subsequent workshop, these themes were validated by Besrour Centre members from Canada and elsewhere. No additional themes have been suggested to this point; however, in subsequent consultation we will further validate themes as they apply to individual institutions and the usefulness of the overall taxonomy.

Box 1. Themes inferred through the Besrour narrative process.

The 17 themes inferred comprised the following:

Advocacy

Stakeholder engagement

Linkage with national public health initiatives

Health systems policies

International partnerships

Interdisciplinary partnerships

Community priorities

Curriculum development and transformation

Undergraduate education

Community- or rural-based education

Rural outreach

Continuing professional development or continuing medical education

Competency-based education

Local champions

Key challenges

Social responsibility

Measuring outcomes

Themes selected encompassed any ideas that were expressed in multiple narratives. They include external influences (eg, international partnerships, national policies), educational methodologies (eg, undergraduate education, rural-based education, continuing professional development or continuing medical education), and a great number of community-oriented topics (eg, community priorities, community-based education, social responsibility).

Narrative highlights.

Thematic analysis continues, but here we highlight some of the stories and the manner in which the process will provide useful and shareable insights into the global development of family medicine.

The linkage between the thematic analysis and the experiences of various schools helps to illustrate both the robustness and the usefulness of the narratives in exploring generalizable observations and the features supporting success in each institute. Thus, for example, the theme of social accountability was highlighted in the story from Tunisia: “The [faculties of medicine of Tunis] set priorities to enhance family medicine by directing the training curriculum for students to priority health needs of the country.”

Themes of stakeholder engagement and community-based education were illustrated in Laos:

A supervised research study [is under way] where they ... survey basic health practices, analyze the data to determine common and priority issues, and determine possible interventions to improve the health of the population ... negotiated with community leaders around areas of perceived need, and once engagement with the village people has been achieved, an intervention is planned.

From Nepal, we heard about advocacy and local champions:

Active advocacy from the GP Association of Nepal (GPAN) [is done] in collaboration with the Nick Simons Institute (NSI). This advocacy group has been approaching government, pushing for a better career ladder and career structure for GPs, particularly in rural areas.

Partnering institutions in Africa included French-, English-, and Portuguese-speaking nations. Partners who were able to attend the Besrour Conference and participate in the narrative project included representatives from Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Mali, and the Aga Khan University of East Africa. North Africa was represented by Palestine and Tunisia. These stories are as rich and diverse as the nations from which they arose. We heard how overseas support and a psychiatrist champion, along with shifting national policies, provided a catalyst in Ethiopia. Participants from Mali reported decentralizing the health care system into the community and creating academic centres using a needs assessment and advocacy. Palestine is shifting from a vertically oriented to a horizontal and holistic health system through family health teams.

In Asia, we heard from participants from Aceh (Indonesia), Nepal, Laos, and China. Once again, the rich tapestry lent an opportunity for us to learn collectively. For example, we heard how the Patan Academy of Health Sciences in Nepal and the University of Health Sciences of Laos are focusing on the rural poor and vulnerable by providing community-based education. In contrast, China is mounting an ambitious national call to train 400 000 family physicians by 2020; Shantou University is leveraging international, dedicated partnerships on curriculum development and faculty training.

From the Central and South American continents, we had delegates attend the conference and participate in the narrative project from the Caribbean island group, Haiti, Brazil, and Chile. From participants in Haiti, we learned about resilience when initial efforts faltered until an international partner helped drive the primary care agenda and commendable local efforts were made. When the Brazilian government determined that health was a right of its citizens and created community-based primary care clinics, it also propelled improved training of its generalist physicians.

The stories are compiled on a College of Family Physicians of Canada website (http://global.cfpc.ca) intended to illustrate the success and strength of our partners as we all work to enhance primary care worldwide through family medicine. There lies an ongoing opportunity for those who work in advocacy for the discipline to learn and share their experiences. Stories are searchable by country, theme, and key word.

Discussion.

Gathering narratives from across the globe has involved intensive co-learning and opportunities for sharing. This project rested entirely on the openness and insights of the partners. It moves beyond the traditional “lessons learned” to a more dynamic identification of strengths in relation to the local context. Rather than an outside observer using a standardized metric to evaluate a health system or program, shared narratives portray what has worked within the local context. Rather than using a comparative metric to identify strengths, the collection of narratives creates a data set to explore common threads and emergent themes.

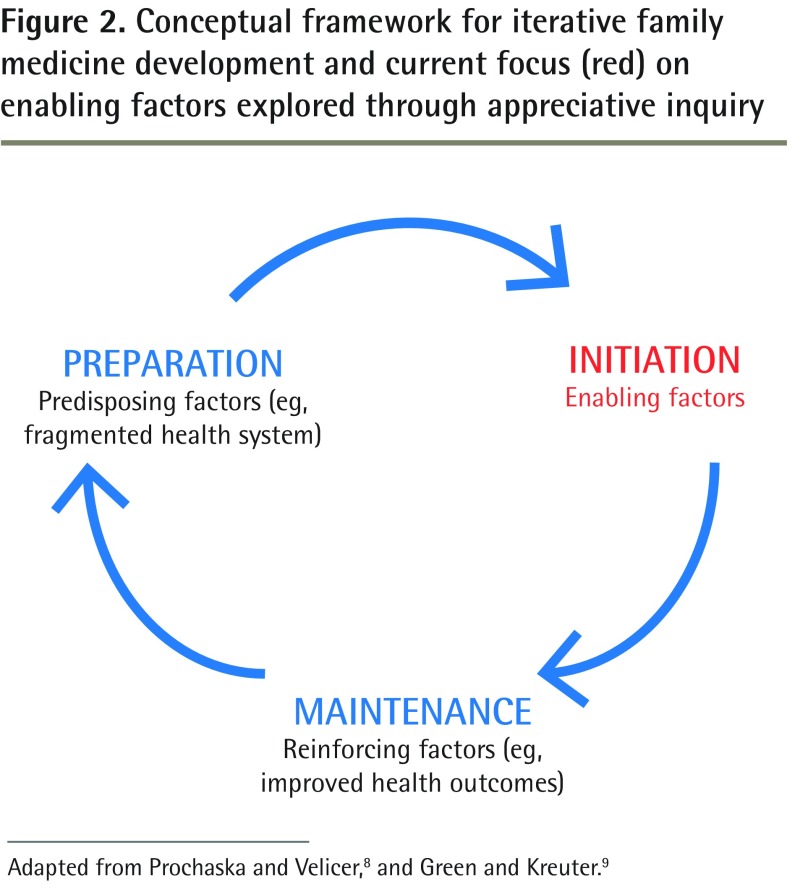

As with any clinical encounter, different contexts will be more or less ready to embark upon the sustained process required for change (Figure 2).8,9 We conceptualize a framework that combines elements of the model of change by Prochaska and Velicer,8 the precede-proceed model by Green and Kreuter,9 and elements of motivational interviewing frameworks that differentiate between importance and confidence when contemplating change.10 Indeed, our appreciative inquiry model is proving especially useful for contexts that have moved beyond precontemplation and are actually contemplating change: those who consider moving forward but perhaps lack the confidence to do so, and for whom a focus on relevant enablers might provide an impetus to move forward. Critically, the narratives emphasize the process as being iterative, circular, and self-reinforcing.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for iterative family medicine development and current focus (red) on enabling factors explored through appreciative inquiry

Adapted from Prochaska and Velicer,8 and Green and Kreuter.9

The process outlined here takes this collection one step further in providing a rigorous analysis of this data set through thematic analysis. This allows the process to exhibit what in complexity theory is called emergence—becoming more than the sum of its parts. A subsequent paper will elaborate this process and reflect the desire of the Besrour initiative itself to ensure that the many relationships between Canadian medical schools and LMIC partners advance the cause of family medicine globally by becoming more than the sum of their own considerable parts.

This process has demonstrated that the narrative process, so crucial to the clinical practice of family physicians, can also be a valid and useful research tool. The narrative process was one that was easily shared and demonstrated a breadth of regional diversity with relatively few examples. This narrative collection and its attendant tools of analysis promises to be a “living laboratory” for the ongoing sharing, refinement, emulation, and application of the experience of building family medicine around the world.

Conclusion

The collection of narratives is a practice that is ancient and profound. The art of medicine has its roots in storytelling. We show here how this process was used to tell the story of family medicine across the globe, taking snapshots in time of a variety of nations’ development. Enhancing the Besrour collaboration through shared experience, these narrative case studies highlight the successes of family medicine development around the world.

The stories stand by themselves. They illustrate the perceived milestones that our partners in low-resource settings identified as critical enabling features in their journey toward family medicine development. Given that it was only half a century ago that Canada embarked on a similar journey, and that we too are fighting ongoing battles for advocacy and role definition, there are opportunities for joint learning and application. This is poignantly true when Canada, which enjoys one of the best health care systems in the world, is constantly feeling resource constraints that threaten the stability of our universal health care system.

To further enhance our understanding of these narratives and to validate the thematic analysis, the next stage of development is the cross-referencing of the thematic analysis of each narrative by authors of the original narrative and new reviewers. This will test the robustness of the thematic “lens,” as well as the accuracy of each analysis and the frequency and possible clustering of themes across the current 16 narratives.

In a subsequent paper the results of this detailed analysis and aggregated observations will feed into a process whereby narratives are updated and searchable. This will ensure these narratives comprise a living document that will be of direct knowledge translation benefit to global partners interested in the enabling factors in the development of family medicine.

In the realm of global health, it is crucial to be mindful of the opportunities for co-learning. The narratives demonstrated holistic, patient-centred practices in a variety of settings; how rural medicine is supported and how community engagement is fostered in resource-poor environments; and that the story of family medicine is a shared one.

Future papers will validate, refine, and apply the tools described in this paper.

Please write to besrour_narratives@cfpc.ca if you wish to become involved in this exciting and innovative process, or to learn more.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

The art of medicine has its roots in storytelling. The Besrour collaboration solicited narratives from its global partners to tell the story of family medicine across the globe, taking snapshots in time of various nations’ development. Enhancing the Besrour collaboration through shared experience, these narrative case studies highlight the successes of family medicine development around the world.

In the realm of global health, it is crucial to be mindful of the opportunities for co-learning. The narratives demonstrated holistic, patient-centred practices in a variety of settings; how rural medicine is being supported and how community engagement is fostered in resource-poor environments; and that the story of family medicine is a shared one.

To further enhance understanding of these narratives and to validate the thematic analysis, the next stage of development is cross-referencing of the thematic analysis of each narrative by authors of the original narrative and new reviewers. This will test the robustness of the thematic “lens,” as well as the accuracy of each analysis and the frequency and possible clustering of themes across the current 16 narratives.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

L’art de la médecine tire ses racines dans la narration de récits. La collaboration Besrour a sollicité de ses partenaires mondiaux des récits narratifs qui racontent l’histoire de la médecine familiale sur la planète et dressent un portrait ponctuel de son développement dans divers pays. Ces études de cas narratives enrichissent la collaboration Besrour grâce au partage des expériences et mettent en évidence les réussites du développement de la médecine familiale dans le monde.

Dans la sphère de la santé mondiale, il est essentiel d’être conscients des possibilités d’apprendre les uns des autres. Les récits narratifs ont mis en lumière des pratiques holistiques et centrées sur le patient dans divers milieux : les façons de soutenir la médecine rurale, les initiatives pour favoriser la mobilisation communautaire dans des environnements où les ressources sont limitées et les points communs dans l’histoire de la médecine familiale.

Pour mieux faire comprendre ces récits narratifs et valider l’analyse thématique, l’étape suivante de l’étude est la référence croisée de l’analyse thématique de chaque récit par les auteurs du récit narratif original et par de nouveaux réviseurs. Cet exercice mettra à l’épreuve la robustesse de « la lentille » thématique, de même que l’exactitude de chaque analyse, et cernera la fréquence et le regroupement possible des thèmes dans les 16 récits narratifs.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation, and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Rouleau K, Ponka D, Arya N, Couturier F, Siedlecki B, Redwood-Campbell L, et al. The Besrour Conferences. Collaborating to strengthen global family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:578–81. (Eng), 587–91 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooperrider DL, Sorensen PF Jr, Whitney D, Yaeger TF, editors. Appreciative inquiry. Rethinking human organization toward a positive theory of change. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weatherhead School of Management . Appreciative inquiry commons. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University; Available from: http://appreciativeinquiry.cwru.edu. Accessed 2017 Jan 9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watkins JM, Stavros JM. Appreciative inquiry: OD in the post-modern age. In: Rothwell RJ, Stavros JM, Sullivan RL, Sullivan A, editors. Practicing organization development. A guide for leading change. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gell-Mann M. The quark and the jaguar. Adventures in the simple and the complex. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Côté L, Turgeon J. Appraising qualitative research articles in medicine and medical education. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):71–5. doi: 10.1080/01421590400016308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion planning. An educational and environmental approach. 2nd ed. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet JE, Ernst D, Borrelli B, Hecht J. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: it sounds like something is changing. Health Psychol. 2002;21(5):444–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]