Abstract

Background

Ischemic optic neuropathy is the most common form of perioperative visual loss, with highest incidence in cardiac and spinal fusion surgery. To date, potential risk factors have been identified in cardiac surgery by only small, single institution studies. To determine the preoperative risk factors for ischemic optic neuropathy, we used the National Inpatient Sample, a database of inpatient discharges for non-federal hospitals in the United States.

Methods

Adults ≥ 18 years of age admitted for coronary artery bypass grafting, heart valve repair or replacement surgery, or left ventricular assist device insertion in National Inpatient Sample from 1998–2013 were included. Risk of ischemic optic neuropathy was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression.

Results

5,559,395 discharges met inclusion criteria with 794 (0.014%) cases of ischemic optic neuropathy. The average yearly incidence was 1.43/10,000 cardiac procedures, with no change during the study period (p = 0.57). Conditions increasing risk were carotid artery stenosis (odds ratio, OR = 2.70), stroke (OR = 3.43), diabetic retinopathy (OR = 3.83), hypertensive retinopathy (OR = 30.09), macular degeneration (OR = 4.50), glaucoma (OR = 2.68), and cataract (OR = 5.62). Female sex (OR = 0.59) and uncomplicated diabetes mellitus type 2 (OR = 0.51) decreased risk.

Conclusion

The incidence of ischemic optic neuropathy in cardiac surgery did not change over the study period. Development of ischemic optic neuropathy after cardiac surgery is associated with carotid artery stenosis, stroke, and degenerative eye conditions.

Introduction

Perioperative visual loss (POVL) is a rare but devastating complication of non-ocular surgery. Ischemic operative neuropathy (ION) is the most common mechanism, with reported cardiac surgery incidence ranging from as high as 1.3% to 0.06%, and most recently estimated at 0.086%.1–3 There is painless vision loss affecting either the anterior (AION) or posterior (PION) optic nerve. AION is more prevalent in cardiac surgical procedures whereas PION is more commonly in posterior spinal fusion surgery.2,4 ION has been well studied in spinal fusion, with risk factors of age, obesity, male sex, blood loss, increased surgical duration, type of surgical positioning frame, and low colloid to crystalloid ratio for fluid therapy.5–7 A recent study suggests ION in spinal fusion has decreased over the past 15 years.8

ION in cardiac surgery has been less studied, and may result from a different mechanism. A 1982 case series suggested hypotension, hypothermia and complement activation as possible risk factors.9 Three retrospective single institution cohort studies did not replicate these findings, but rather identified other risk factors including severe peripheral vascular disease, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time, packed red blood cell (PRBC) units transfused, lowest hemoglobin, non-PRBC transfusion, and pre-operative angiogram < 48 h prior to the procedure.1,2,4 However, these studies are limited by small size, with a combined total of only 34 cases, and thus may lack generalizability. Moreover, they are now > 15 years old. Since then cardiac surgery has changed considerably, with 25% fewer coronary artery bypass graft procedures (CABG), and a significant increase in left ventricular assist device insertion.10,11 Using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), Shen et al performed the largest analysis to date of ION in cardiac surgery and identified male sex and an increased Charlson index score as risk factors.3 However, the study did not address factors specific to cardiac surgery such as co-morbidities indicative of severe vascular disease, type of cardiac surgery, and use of CPB.

Chronic ophthalmic disease is a possible risk factor due to local hemodynamic impairment known to be associated with glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.12,13 A recent study supported this notion by demonstrating increased prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in diabetics with incident microvascular ocular motor palsies.14 On a broader level, a large body of literature supports associations between vascular disease of the eye with both acute and chronic cerebrovascular disease that persist after accounting for potentially common causes such as systemic vascular disease.15

Based upon previous studies, we hypothesized that specific patient medical conditions are associated with ION after cardiac surgery and that these are distinct from ION after posterior spine fusion surgery. Moreover, we also hypothesized specific surgical elements such as CABG and use of cardiopulmonary bypass would also be associated with ION. To test our hypotheses, we analyzed the NIS to identify risk factors associated with ION after cardiac surgery. Additionally, because of changes in procedure volume in cardiac surgery during the study period we evaluated the incidence and trends in ION after cardiac surgery involving CABG, heart valve repair or replacement surgery, and left ventricular assist device procedure.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

The NIS of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) is directed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).16 It is an approximate 20% stratified survey sample of non-federal U.S. hospital discharges derived from a typical hospital discharge abstract. The NIS includes age, race, total charges, hospital characteristics including teaching status and location, discharge disposition, and 25 diagnostic and 15 procedural codes defined in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).17 Beginning in 2012, the NIS was redesigned to improve national estimates, by sampling all participating hospitals rather than a subset.16 To ensure accurate weighting of the sample across multiple years, AHRQ has provided updated discharge weights for the years 1998–2011. We used these updated “trend weights,” combined with the “survey” function for all patient level analysis and regressions, as previously described.8 The University of Chicago and University of Illinois Institutional Review Boards deemed the study exempt from IRB review since there are no patient identifiers.

Data Classification

Our retrospective analysis included inpatient discharges of adults ≥ 18 years old with an ICD-9-CM procedure code for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG, 36.10–36.16, 36.17, 36.19), valve repair or replacement (35.1–35.14, 35.2–35.28), and left ventricular assist device (37.66) procedures from 1998 to 2013. Insertion of an intra-aortic counter pulsation balloon pump (37.61) and cardiopulmonary bypass (39.61, 39.62) were included as secondary procedures. There were no cases of ION in heart transplant, atrial and ventricular septal defect repair, and congenital heart surgery in those ≥ 18 years, therefore these procedures were excluded.

To compare the incidence of ION in a non-surgical inpatient population we analyzed patients with significant coronary artery disease requiring a percutaneous intervention (PCI). Coronary artery disease was chosen since the majority of ION cases were associated with the CABG procedure. This group consisted of adults ≥18 years old with an ICD-9-CM procedure code for percutaneous coronary intervention, and placement of either a bare metal (36.06) or drug eluting stent (36.07). Patients with a concurrent procedure code for either CABG, valve repair or replacement, or left ventricular assist device procedure on the same admission were excluded from the PCI cohort. Surgical and PCI patients discharged with a principal or secondary diagnostic ICD-9-CM code of ischemic optic neuropathy (377.41) were considered to have developed ION during the hospitalization.

Patient and Surgical Characteristics

Patient characteristics analyzed included: age (years, continuous variable), sex, length of hospital stay (days), yearly inflation-adjusted total hospital charges, type of admission (elective, emergent), discharge status (routine, short term hospital, home health care, died, other), and race.18 Potential risk factors were identified prior to analysis based upon previous case series, large database reviews, and case reports as recommended in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.19 See table, Supplemental Digital Content 1 for ICD-9-CM patient comorbidity codes. We studied: obesity, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), smoking, hypertension, diabetes type 1 or 2 uncomplicated, diabetes with renal manifestations, diabetes with neurological manifestations, diabetic retinopathy, diabetes with peripheral circulatory disorders, hypertensive retinopathy, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, cataract, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, carotid artery stenosis, stroke (post-operative, acute, embolic and thrombotic), blood transfusion, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure (systolic and diastolic), pulmonary hypertension, and anemia. Degenerative eye conditions were included because they may predispose to ION.20,21 To investigate concern that chronic ophthalmic conditions could appear falsely associated with ION due to increased frequency of eye exams in affected patients, cataract was also studied as a patient comorbidity as it should not act as a risk factor for ION.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was ION during an admission for one of the three cardiac surgical procedures, CABG, valve repair or replacement, left ventricular assist device, or for PCI. AHRQ trend weights, and the survey functions of STATA were used for all national estimates and regressions.8 Dividing individual survey estimates from the total count can lead to rounding variation in the NIS dataset, as seen in the total number of ION cases when compared to cases of ION for the different cardiac procedures. Data were complete except for race (n=1,261,433 [23%]), type of admission (n=1,692,552 [30%]), age (n=433, [0.01%]), length of stay (n=185 [<0.01%]) and discharge status (n=7,316 [0.1%]). Due to high rates of missing data for race and type of admission they were not included in the univariable and multivariable analysis.

Patient characteristics for all cardiac procedures were compared for 1998–2013 using the national estimates, and reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used chi-square with a second order Rao-Scott correction to detect differences in the incidence of ION in the different cardiac surgery procedures and differences in cardiac surgery procedure rates during the study period. The mean incidence of ION in cardiac surgery and PCI was compared using an adjusted Wald test.22 Rates of cardiac surgical procedures were calculated as procedures per million adults (>18 years old) in the U.S population using U.S Census data.23 A univariate logistic regression was performed for patient characteristics, primary and secondary cardiac procedures to identify covariates associated with ION. Characteristics and procedures with P value ≤0.2 were then included in a multivariable logistic regression. Those with P value ≤0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression were considered significant and the odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals and P value were reported. Changes in the temporal trend of ION incidence was assessed using multivariable logistic regression, modeling year as a continuous variable and including primary cardiac procedures to account for changes in procedure volume over time.

The variance inflation factor (VIF) examined collinearity. VIF > 5 identified possible collinearity between predictors. None of the identified predictors had VIF > 5, which suggests no collinearity of predictors. Pearson’s goodness-of-fit was used to assess the multivariable model fit and was not significant at the 5% level (P =0.127), thus the multivariable model could not be rejected. STATA v14.0-MP (Stata, College Station, TX) was used for all data analysis.

Results

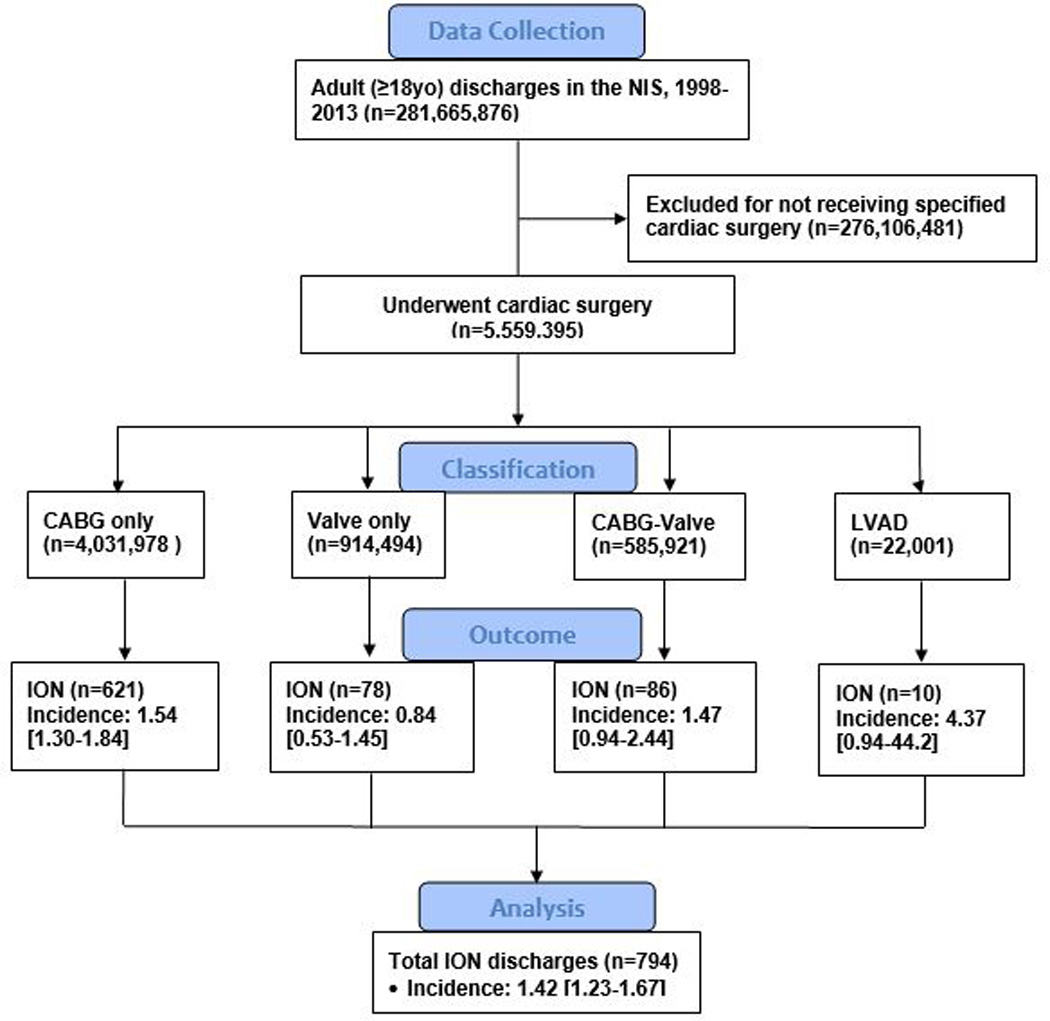

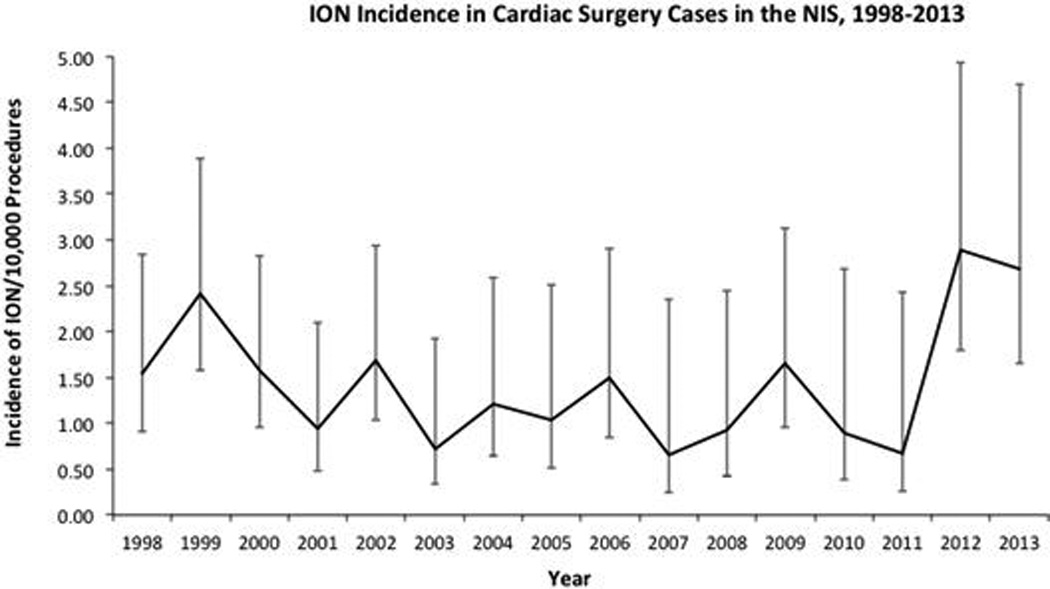

There were an estimated 5,559,395 discharges between 1998–2013 with procedure codes for a CABG, valve repair or replacement or left ventricular assist device (Figure 1). A diagnosis of ION was documented in 794 of those procedures, corresponding to an average yearly incidence of 1.43/10,000 cardiac surgeries [CI: 1.23–1.67] (Table 1). After adjusting for changes in procedural volume there was no significant change in yearly incidence of ION in cardiac surgery (OR: 1.01, P = 0.574) (Figure 2). There were an estimated 9,520,478 discharges with procedure codes for PCI, and 206 had a diagnosis for ION, see figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which is a figure illustrating the incidence of ION in PCI. The incidence of ION in PCI was 0.22/10,000 [CI: 0.16–0.30], significantly less than that for patients undergoing isolated CABG [P=0.0001].

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram of ION in cardiac surgery.

Data collection was through patient discharges recorded in the NIS from 1998 to 2013. Only patients ≥18 years old who underwent a specified cardiac procedure (CABG-only, valve repair or replacement-only, CABG-valve repair or replacement as a combined procedure, or left ventricular assist device) were included in the analysis, and all other patients were excluded. The primary outcome, ION, was reported as volume (n) and incidence per 10,000 [95% confidence interval]. Results are nationwide estimates using NIS weighting and STATA survey function.

Abbreviations: CABG-only = only received coronary artery bypass graft; CABG-Valve = received both coronary artery bypass graft and cardiac valve repair or replacement; ION = ischemic optic neuropathy; LVAD = received left ventricular assist device; NIS = National Inpatient Sample; Valve-only = only received cardiac valve repair or replacement.

Table 1.

National Estimates of ION in Cardiac Surgery Cases in the NIS, 1998–2013.

| Year | Cardiac Cases [95% CI] | ION [95% CI] | ION Incidence (per 10,000) [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 422,329 [372,256–472,401] | 65 [27–103] | 1.54 [0.91–2.84] |

| 1999 | 399,492 [344,505–454,480] | 96 [45–147] | 2.41 [1.58–3.88] |

| 2000 | 429,030 [381,780–476,281] | 68 [26–110] | 1.58 [0.95–2.83] |

| 2001 | 434,215 [385,513–482,916] | 41 [11–70] | 0.93 [0.48–2.10] |

| 2002 | 406,079 [357,699–454,459] | 68 [15–121] | 1.68 [1.03–2.94] |

| 2003 | 392,455 [347,906–437,004] | 28 [3–54] | 0.73 [0.33–1.92] |

| 2004 | 348,837 [313,534–384,140] | 42 [12–73] | 1.21 [0.64–2.58] |

| 2005 | 325,036 [286,843–363,230] | 34 [7–60] | 1.04 [0.51–2.51] |

| 2006 | 353,147 [311,112–395,181] | 53 [19–86] | 1.49 [0.84–2.91] |

| 2007 | 297,131 [266,279–327,982] | 19 [0–40] | 0.65 [0.24–2.35] |

| 2008 | 312,092 [281,506–342,678] | 29 [7–51] | 0.93 [0.42–2.45] |

| 2009 | 331,771 [288,738–374,804] | 53 [17–89] | 1.65 [0.95–3.13] |

| 2010 | 271,885 [245,556–298,154] | 24 [2–47] | 0.90 [0.38–2.69] |

| 2011 | 278,957 [245,296–312,619] | 19 [0–38] | 0.67 [0.25–2.43] |

| 2012 | 277,570 [262,438–292,703] | 80 [37–123] | 2.88 [1.80–4.94] |

| 2013 | 279,400 [264,082–294,718] | 75 [34–116] | 2.68 [1.65–4.69] |

| Total | 5,559,395 [5,194,174–5,924,617] | 794 [638–951] | 1.43 [1.23–1.67] |

To calculate incidence of ION per 10,000 yearly estimates of ION was divided by yearly estimates of cardiac surgical procedures. Estimates from the NIS were created using the trend weights and stratum variables from the NIS and the survey function of STATA. Cardiac cases include: coronary artery bypass grafts only, coronary artery bypass graft with valve repair or replacement, valve repair or replacement only, and left ventricular assist device insertion.

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; ION = ischemic optic neuropathy; NIS = National Inpatient Sample.

Figure 2. ION Incidence in Cardiac Surgery Cases in the NIS, 1998–2013.

Results are nationwide estimates using NIS weighting and STATA survey function. After adjusting for changes in procedural volume in the multivariable analysis, there was no significant change in yearly incidence of ION (OR: 1.01, P = 0.574). Cardiac surgery cases include: coronary artery bypass grafts only, coronary artery bypass graft with valve repair or replacement, valve repair or replacement only, and left ventricular assist device insertion. To calculate incidence of ION per 10,000, yearly estimates of ION were divided by yearly estimates of cardiac surgical procedures. Errors bars are 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations: ION = ischemic optic neuropathy; NIS = National Inpatient Sample.

Isolated CABG surgery accounted for the highest volume of diagnoses of ION (621/794, 78%), followed by a combined CABG and valve repair or replacement (86/794, 11%), valve repair or replacement alone (78/794, 10%), and left ventricular assist device (10/794, 1.3%) (Figure 1). The incidence of ION for each procedure category is illustrated in Figure 1. The incidence of ION was not different between the different cardiac surgery procedures [P=0.0596].

In Figure 3 are changes in cardiac surgery procedures from 1998 to 2013. There was a 60% decrease in CABG as the sole procedure from 1998 to 2013 (1,725 to 686 per million adults), 1,092% increase in left ventricular assist device (1.3 to 14.2 per million), 53% increase in valve repair or replacement alone (206 to 315 per million) and a 22% decrease in combined CABG and valve repair or replacement (176 to 137 per million) [p=0.0001].

Figure 3.

To calculate incidence of cardiac procedures per 1 million, yearly estimates of each procedure type were divided by the yearly US population estimate based on US Census Bureau data (http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/index.html). Results are nationwide estimates using NIS weighting and STATA survey function. There was a 60% decrease in CABG as the sole procedure from 1998 to 2013 [1,725 to 686 per million adults], 1,092% increase in LVAD (1.3 to 14.2 per million), 53% increase in valve replacement alone (206 to 315 per million) and a 22% decrease in combined CABG-Valve (176 to 137 per million) [p=0.0001]. Cardiac procedure types include: (A) CABG only, (B) Valve repair or replacement only, (C) CABG-Valve repair or replacement, and (D) LVAD. Errors bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Abbreviations: CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CABG-Valve = coronary artery bypass graft and cardiac valve repair or replacement; LVAD = ventricular assist device insertion; NIS = National Inpatient Sample; Valve = cardiac valve repair or replacement.

Characteristics of patients with a cardiac surgical procedure are presented in Table 2 and characteristics of patients with a PCI are presented in the table, Supplemental Digital Content 3.

Table 2.

Characteristics and Univariable Analysis of All Cardiac Surgery Cases with and without ION in the NIS, 1998 to 2013.

| Cases | All Cases: ION | All Cases: Unaffected |

Odds Ratio | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients: number of discharges | 794 | 5,558,601 | |||

| Mean length of stay days (95% CI) | 12.0 (10.1– 13.8) |

10.1 (10.0–10.3) | 1.004 | 0.0001 | |

| Mean total charges, $ (95% CI) (inflation adjusted to 2013) |

123,539 (103,723– 143,354) |

129,556 (125,179–133,932) |

1.00 | 0.586 | |

| Type of admission |

Elective (%) | 254 (32.0) | 1,993,517 (35.9) | ||

| Non-elective (%) | 271 (34.1) | 1,872,802 (33.7) | |||

| Missing (%) | 270 (34.0) | 1,692,282 (30.4) | |||

| Discharge status |

Routine (%) | 355 (44.7) | 2,776,293 (49.9) | Ref | - |

| Short-term hospital (%) |

<10 (<1.3) | 46,826 (0.8) | 0.79 | 0.823 | |

| Home health care (%) |

287 (36.1) | 1,606,369 (28.9) | 1.40 | 0.066 | |

| Other (%) | 144 (18.1) | 934,923 (16.8) | 1.21 | 0.385 | |

| Died (%) | <10 (<1.3) | 186,874 (3.4) | 0.20 | 0.117 | |

| Missing (%) | <10 (1.3) | 7,316 (0.1) | 1.0 | --- | |

| Race | White (%) | 561 (70.7) | 3,515,288 (63.2) | ||

| Black (%) | 30 (3.8) | 266,398 (4.8) | |||

| Hispanic (%) | <10 (<1.3) | 270,530 (4.9) | |||

| Asian or Pacific Islander (%) |

<10 (<1.3) | 87,460 (1.6) | |||

| Native American (%) | <10 (<1.3) | 18,738 (0.3) | |||

| Other (%) | 24 (3.0) | 138,925 (2.5) | |||

| Missing (%) | 170 (21.4) | 1,261,263 (22.7) | |||

| CABG only | 1-vessel (%) | 77 (12.4) | 574,363 (14.2) | Ref | - |

| 2-vessel (%) | 272 (43.8) | 2,353,560 (58.4) | 1.75 | 0.032 | |

| 3-vessel (%) | 181 (29.1) | 1,259,978 (31.3) | 1.20 | 0.473 | |

| 4-vessel (%) | 81 (13.0) | 659,428 (16.4) | 1.02 | 0.940 | |

| Unspecified # of vessels (%) |

10 (1.6) | 184,029 (4.6) | 0.52 | 0.311 | |

| Total CABG only | 621 (78.2) | 4,031,357 (72.5) | 1.35 | 0.143 | |

| Valve only | 78(9.8) | 919,417 (16.5) | 0.55 | 0.027 | |

| CABG and Valve | 86 (10.8) | 585,836 (10.5) | 1.03 | 0.899 | |

| LVAD | 10 (1.3) | 21,991 (0.40) | 3.09 | 0.129 | |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump (%) | 54 (6.8) | 447,182 (8.0) | 0.83 | 0.562 | |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 597 | 4,436,073 | 0.76 | 0.151 | |

| Age group (Years) |

<57 (%) | 226 (28.5) | 1,378,470 (24.8) | Ref | - |

| 57–65 (%) | 193 (24.3) | 1,183,066 (21.3) | 1.00 | 0.982 | |

| 66–74 (%) | 220 (27.7) | 1,612,801 (29.0) | 0.83 | 0.409 | |

| >75 (%) | 155 (19.5) | 1,384,265 (24.9) | 0.68 | 0.105 | |

| Sex | Female (%) | 189 (23.8) | 1,771,498 (31.9) | 0.67 | 0.033 |

| Male (%) | 605 (76.1) | 3,786,443 (68.1) | Ref | - | |

| Obesity (%) | 108 (13.6) | 621,890 (11.2) | 1.25 | 0.329 | |

| Obstructive sleep apnea (%) | 24 (3.0) | 145,126 (2.6) | 1.19 | 0.718 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 432 (54.4) | 2,668,295 (48.0) | 1.29 | 0.123 | |

| Smoking (%) | 197 (24.8) | 1,495,130 (26.9) | 0.89 | 0.572 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 549 (69.1) | 3,630,926 (65.3) | 1.19 | 0.319 | |

| DM type 1 without complications (%) |

15 (1.9) | 93,954 (1.7) | 0.09 | 0.879 | |

| DM type 2 without complications (%) |

113 (14.2) | 1,364,385 (24.5) | 0.51 | 0.004 | |

| Diabetic retinopathy (%) | 48 (6.0) | 67,719 (1.2) | 5.21 | 0.001 | |

| DM with renal manifestations (%) | 20 (6.0%) | 72,524 (1.3) | 1.92 | 0.216 | |

| DM with neurological manifestations (%) |

24 (3.0%) | 104,678 (1.9) | 1.65 | 0.288 | |

| DM with peripheral circulatory disorders (%) |

<10 (<1.3) | 17,637 (0.3) | 1.0 | -- | |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 72 (9.1) | 279,146 (5.0) | 1.90 | 0.020 | |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 714 (89.9) | 4,731,611 (85.1) | 1.55 | 0.132 | |

| Carotid artery stenosis (%) | 77 (9.7) | 204,815 (3.7) | 2.82 | 0.001 | |

| Stroke (%) | 44 (5.5) | 120,700 (2.2) | 2.62 | 0.005 | |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 197 (24.8) | 1,696,490 (30.5) | 0.75 | 0.139 | |

| Congestive heart failure (%) | 139 (17.5%) | 1,306,558 (23.5) | 0.69 | 0.108 | |

| Cardiogenic shock (%) | 30 (3.8%) | 180,784 (3.3) | 1.15 | 0.729 | |

| Pulmonary hypertension (%) | 39 (4.9%) | 282,533 (5.1) | 0.97 | 0.936 | |

| Anemia (%) | 267 (33.6) | 1,745,545 (31.4) | 1.11 | 0.555 | |

| Blood transfusion (%) | 184 (23.2) | 1,272,784 (22.9) | 1.01 | 0.941 | |

| Acute kidney injury (%) | 55 (6.9) | 539,574 (9.7) | 0.69 | 0.261 | |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 30 (3.8) | 279,727 (5.0) | 0.73 | 0.472 | |

| Glaucoma (%) | 28 (3.5) | 65,253 (1.2) | 3.08 | 0.009 | |

| Age-related macular degeneration (%) |

11 (1.4) | 17,744 (0.3) | 4.29 | 0.046 | |

| Hypertensive retinopathy (%) | <10 (<1.3) | 1,502 (0.03) | 46.44 | 0.001 | |

| Cataract (%) | 21 (2.6) | 15,643 (0.3) | 9.46 | 0.001 | |

Results are nationwide estimates using NIS weighting and STATA survey function. Numbers are presented as count estimates or means with percent in parentheses and respective 95% confidence intervals in brackets when indicated. Results with n < 10 could not be reported due to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality regulations. See table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes used to identify noted characteristics. Total charges were inflation adjusted to 2013 dollars using Bureau of Labor Statistics (http://www.bls.gov/data/). Cardiac cases include procedures with: only coronary artery bypass grafts, coronary artery bypass grafts with valve repair or replacement, only cardiac valve repair or replacements, and left ventricular assist device insertions.

Abbreviations: CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CABG and Valve= coronary artery bypass graft and valve repair or replacement; CI = confidence interval; DM=diabetes mellitus; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; ION = ischemic optic neuropathy; LVAD = left ventricular assist device; NIS = National Inpatient Sample; Ref= Reference category; Valve = cardiac valve repair or replacement.

A univariable analysis was performed for all cardiac surgery patient characteristics, primary and secondary cardiac procedures (Table 2). Significant characteristics and procedures from the univariable analysis (P <0.20) were combined to create a multivariable logistic regression (Table 3). Patient characteristics, from the multivariable model, associated with increased odds of ION include carotid artery stenosis (OR 2.70, CI: 1.52–4.80, P = 0.001), stroke (OR 3.43, CI: 1.73–6.80, P = 0.0004), diabetic retinopathy (OR: 3.83, CI: 1.84–7.95, P = 0.0003), hypertensive retinopathy (OR: 30.09, CI: 6.21–145.64, P = 0.0001), glaucoma (OR 2.68, CI 1.04–6.93, P = 0.042), age related macular degeneration (OR: 4.50, CI: 1.13–17.87, P = 0.032), and cataract (OR: 5.62, CI:1.71–18.45, P = 0.004)(Figure 4A). Female sex (OR 0.59, CI: 0.38–0.92, P = 0.019) and uncomplicated diabetes mellitus type 2 (OR 0.51, CI: 0.32–0.83, P = 0.006) were associated with lower odds ratios (Figure 4B). The primary procedures associated with increased odds of ION were left ventricular assist device (OR: 13.82, CI: 1.75–109.01, P = 0.013), and two-vessel CABG (OR: 1.78, CI: 1.04–3.06, P = 0.035)(Figure 4A). CPB was not associated with increased odds of ION (OR 0.78 P = 0.219).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis for ION for Cardiac Surgery Cases in the NIS, 1998 to 2013.

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1.01 | 0.97–1.06 | 0.574 | |

| Age group (years) |

<57 | Reference | ||

| 57–65 | 0.94 | 0.60–1.48 | 0.806 | |

| 66–74 | 0.77 | 0.48–1.24 | 0.286 | |

| >75 | 0.64 | 0.37–1.10 | 0.106 | |

| Sex | Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.59 | 0.38–0.92 | 0.019 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.16 | 0.81–1.67 | 0.425 | |

| DM type 2 without complications |

0.51 | 0.32–0.83 | 0.006 | |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 3.83 | 1.84–7.95 | 0.0003 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.44 | 0.80–2.59 | 0.222 | |

| Carotid artery stenosis | 2.70 | 1.52–4.80 | 0.001 | |

| Stroke | 3.43 | 1.73–6.80 | 0.0004 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.84 | 0.55–1.28 | 0.417 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.77 | 0.47–1.26 | 0.297 | |

| Glaucoma | 2.68 | 1.04–6.93 | 0.042 | |

| Age-related macular degeneration |

4.50 | 1.13–17.87 | 0.032 | |

| Hypertensive retinopathy | 30.09 | 6.21–145.84 | 0.0001 | |

| Cataract | 5.62 | 1.71–18.45 | 0.004 | |

| CABG | 1-vessel | Reference | ||

| 2-vessel | 1.78 | 1.04–3.06 | 0.035 | |

| 3-vessel | 1.23 | 0.72–2.09 | 0.445 | |

| 4-vessel | 1.04 | 0.53–2.06 | 0.903 | |

| Unspecified # of grafts |

0.50 | 0.14–1.79 | 0.288 | |

| Valve | 1.25 | 0.70–2.25 | 0.447 | |

| LVAD | 13.82 | 1.75–109.01 | 0.013 | |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 0.78 | 0.52–1.16 | 0.219 | |

Stroke, carotid artery stenosis, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, diabetic and hypertensive retinopathy, cataract, LVAD and two-vessel CABG were associated with increased risk of post-operative ION. Female gender and uncomplicated diabetes type II were associated with a decreased risk of post-operative ION. Results are nationwide estimates using NIS weighting and STATA survey function. A multivariate logistic regression was performed including all patient characteristics and procedures that were significant (P <0.20) in the univariate analysis. In the multivariable analysis, a p value ≤ 0.05 was used to identify significant risk factors. Results are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs. Cardiac cases include: coronary artery bypass grafts, coronary artery bypass grafts with valve repair or replacement, cardiac valve repair or replacements, and left ventricular assist device insertions.

Abbreviations: CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CI = confidence interval; DM type 2 without complications = diabetes mellitus type 2 without ophthalmic, renal, neurological, or peripheral circulatory complications; ION = ischemic optic neuropathy; LVAD = left ventricular assist device insertion; NIS = National Inpatient Sample; Reference= Reference category; Valve = cardiac valve repair or replacement.

Figure 4. Odds ratios for conditions that increase and decrease odds of ION in Cardiac Surgery.

Odds ratios from the multivariable analysis for patient conditions that increase and decrease odds of developing perioperative ischemic optic neuropathy after cardiac surgery. (A): Conditions and procedures that increase odds of developing ION (odds ratio and 95% CI’s). Of note, hypertensive retinopathy and left ventricular assist device procedure were left off of the graph secondary to large confidence intervals. (B): Conditions that decrease odds of developing ischemic optic neuropathy after cardiac surgery (odds ratios and 95% CI’s).

Abbreviations: CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CI = confidence interval; ION = ischemic optic neuropathy.

Discussion

The incidence of ION in CABG, valve repair or replacement, and left ventricular assist device, from 1998–2013, was 1.43/10,000 with no significant trend over the study period. The estimated incidence of ION after PCI, in the same database, was 0.22/10,000, near the lower end of prior national estimates of ION incidence in the general adult population at 2–10/100,000.24,25 The seven-fold higher incidence of ION in cardiac surgery as compared to PCI and prior national estimates supports previous studies identifying cardiac surgery as high risk for developing ION, and suggests our findings are due to the development of ION during the peri-operative period, and not a pre-existent diagnosis. Overall no differences in the incidence of ION were identified between the different cardiac surgeries; however, in the multivariable analysis left ventricular assist device and two vessel CABG were associated with increased odds of ION. Two vessel CABG accounted for the highest percentage of isolated CABG procedures and diagnoses of ION; although this was accounted for in the multivariable analysis. It should be noted that left ventricular assist device procedural volume was smaller relative to the other cardiac surgeries, which led to wide confidence intervals for the estimate, thus the result should be interpreted cautiously.

Carotid artery stenosis and stroke were associated with increased risk of ION in our study. Carotid artery stenosis has been listed in numerous case reports as a diagnosis in affected patients and atherosclerosis was previously identified in a single center retrospective cohort as a risk factor.2,9,26,27 However, neither stroke nor carotid stenosis have been identified as risk factors for spontaneously (non-perioperative) occurring ION.28,29 Taken together, these findings suggest that, in cardiac surgery, hypotension, systemic inflammation, or other as yet unknown perioperative mechanisms, may interact with already decreased perfusion via the carotid circulation to heighten the risk of ION.

Our study identified chronic eye conditions associated with altered posterior eye circulation such as glaucoma, age related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and hypertensive retinopathy as risk factors in perioperative ION. Glaucoma and age related macular degeneration may predispose the optic nerve to ischemia due to impaired autoregulation of blood flow.30–32 Similarly, diabetic retinopathy and hypertensive retinopathy are characterized with endothelial damage, a leaky blood-retinal barrier, vascular occlusion, and ischemia, leading to neovascularization.33 Development of ION may be associated with these conditions due to impaired microcirculation diffusely within the eye including the optic nerve. Thus, these degenerative eye conditions could be a marker of more widespread ocular circulatory abnormalities.34 A 2014 analysis of posterior spine fusion surgery in the NIS found an increased risk of visual loss in patients with diabetes with end organ damage; but, the association with ION is unclear as the study included discharges with cortical blindness, retinal artery occlusion in addition to ION.35

These chronic degenerative eye conditions may be markers of increased risk of ION after cardiac surgery, but the results should be interpreted cautiously. Patients that developed perioperative ION likely underwent a detailed ophthalmologic exam to confirm the diagnosis leading to a heightened diagnosis intensity of degenerative eye conditions.36 Increased diagnosis intensity may have led to the association seen between ION and cataract, as there is no theoretical reason for its association. In contrast, glaucoma requires multiple exams and more sophisticated technology for a diagnosis and an initial diagnosis was unlikely to occur during the hospital admission for cardiac surgery.37

Female sex and uncomplicated diabetes were associated with a decrease in the odds of ION after cardiac surgery. The female visual pathway is not known to anatomically differ vs the male visual pathway; however hormonal factors such as estrogen may play a role. Estrogen improves vascular function and decreases atherosclerosis; however, female sex had decreased odds of ION in our study even when controlling for vascular disease and carotid artery stenosis in the multivariable regression leaving the mechanism for this decrease unclear.38,39 The reason why ION risk in this study differed between uncomplicated diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic retinopathy is not known and will require further study.

ION was not associated with factors specific to cardiac surgery that may decrease optic nerve blood flow or embolic events, including cardiopulmonary bypass, cardiogenic shock, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary hypertension and anemia.1,2,4 Several case series and case reports of ION after cardiac surgery identified anemia, blood loss, and lowest hemoglobin level as possible risk factors for ION; however, we did not find anemia or transfusion as significant risk factors. Kalyani found a trend towards a perioperative change in hemoglobin levels and risk of ION but not a significant association.4 Nutall and Shapira identified low post-operative hemoglobin concentrations as an independent risk factor for ION in cardiac surgery after CPB.2 In the NIS these data may not accurately reflect perioperative hemoglobin values.

Our study has limitations secondary to using an administrative database. The NIS is a stratified probability sample of in-patient discharges, previously hospitals, for all non-federal hospitals in the United States. As such, because ION is a rare event over sampling or over weighting of discharges containing a diagnosis of ION may have increased the incidence of ION. However, the NIS is a robust 20% sample of the entire NIS universe and has been rigorously validated.40 Discharge records are susceptible to ICD-9-CM coding errors for a diagnosis of ION. The incidence of ION is low and small errors in diagnostic coding could have a large impact on our findings. However, our un-weighted sample size is > 1 million admissions, which mitigates systematic reporting bias and previous studies have used the NIS to identify the incidence of ION in various surgical populations.8

Our study is limited to identifying patient conditions and surgical procedures associated with increased odds of ION after cardiac surgery. As such, patient conditions reported in the NIS using ICD-9-CM codes may not accurately reflect the clinical spectrum of severity, such as in cardiogenic shock or anemia. Thus, while our study did not find a diagnosis of anemia to be a significant risk factor for developing ION it is possible that the lack of granularity may have impacted our results. Furthermore, the NIS does not contain any intraoperative information about the anesthetic or intraoperative care such as duration of cardiopulmonary bypass. Additionally, ICD-9-CM codes do not exist for certain aspects of the procedure such as re-do sternotomy, which may impact the development of ION.

The temporal relationship between a diagnosis of ION and the timing of the cardiac surgery cannot be determined in the NIS, thus the cardiac surgery population may have had a higher baseline prevalence of ION. However, the seven-fold higher incidence of ION after CABG as compared to PCI and previous national estimates strongly suggests that the majority of ION we observed occurred after cardiac surgery. The severity of visual loss cannot be determined from the database as well as longitudinal follow-up for progression or improvement after discharge. The NIS represents a single inpatient admission and does not contain any patient identifiers to allow patients to be identified for follow-up.

In conclusion, cardiac surgery has an incidence of perioperative ION with an average yearly incidence of 1.43/10,000 procedures; the majority of the cases were associated with isolated CABG. This incidence was about 7 times that of a comparable inpatient group undergoing percutaneous cardiac intervention, as well as the known incidence of spontaneously occurring ION in the general population. The yearly incidence has not changed despite decreases in CABG, increases in left ventricular assist device, and an overall decrease in cardiac surgery volume between 1998 and 2013. ION is most frequently associated with carotid artery stenosis, stroke, male sex, degenerative eye conditions, two-vessel CABG, and left ventricular assist device. Uncomplicated diabetes type 2 and female sex were associated with a lower risk of ION. Further research is needed to identify potential therapeutic interventions to decrease the risk of this rare and devastating complication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

Funding was provided by National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland) grants RO1 EY10343 to Dr. Roth, UL1 RR024999 to the University of Chicago Institute for Translational Medicine, UL1TR002003 to the University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Clinical and Translational Science, K23 EY024345 to Dr. Moss, Core Grant P30 EY001792 to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences of the University of Illinois, the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Summer Research Program (Ms. Matsumoto), and an Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) to the University of Illinois Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

Dr. Roth has served as an expert witness in cases of perioperative eye injuries on behalf of patients, physicians, and hospitals.

The authors are grateful to Ms. Chuanhong Liao, MS, Senior Biostatistician Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Chicago, for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The other authors report no competing interests.

Previous presentation

This study was presented in part at the Upper Midwest Neuro-ophthalmology Group Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois, July 22, 2016

Contributor Information

Daniel S. Rubin, Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care, the University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Monica M. Matsumoto, Pritzker School of Medicine of the University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Heather E. Moss, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, & Department of Neurology and Rehabilitation, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Charlotte E. Joslin, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, College of Medicine; Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Avery Tung, Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care, the University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Steven Roth, Department of Anesthesiology, & Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago; Professor Emeritus, Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care; The Center for Health and the Social Sciences, University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Shapira OM, Kimmel WA, Lindsey PS, Shahian DM. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy after open heart operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:660–666. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)01108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nuttall GA, Garrity JA, Dearani JA, Abel MD, Schroeder DR, Mullany CJ. Risk factors for ischemic optic neuropathy after cardiopulmonary bypass: a matched case/control study. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1410–1416. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200112000-00012. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen Y, Drum M, Roth S. The prevalence of perioperative visual loss in the United States: a 10-year study from 1996 to 2005 of spinal, orthopedic, cardiac, and general surgery. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1534–1545. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b0500b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalyani SD, Miller NR, Dong LM, Baumgartner WA, Alejo DE, Gilbert TB. Incidence of and risk factors for perioperative optic neuropathy after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Postoperative Visual Loss Study G. Risk factors associated with ischemic optic neuropathy after spinal fusion surgery. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:15–24. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823d012a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Practice advisory for perioperative visual loss associated with spine surgery: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Visual Loss. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:274–285. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c104d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patil CG, Lad EM, Lad SP, Ho C, Boakye M. Visual loss after spine surgery: a population-based study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:1491–1496. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318175d1bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin DS, Parakati I, Lee LA, Moss HE, Joslin CE, Roth S. Perioperative Visual Loss in Spine Fusion Surgery: Ischemic Optic Neuropathy in the United States from 1998 to 2012 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:457–464. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney PJ, Breuer AC, Selhorst JB, Waybright EA, Furlan AJ, Lederman RJ, Hanson MR, Tomsak R. Ischemic optic neuropathy: a complication of cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Neurology. 1982;32:560–562. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim LK, Looser P, Swaminathan RV, Minutello RM, Wong SC, Girardi L, Feldman DN. Outcomes in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery in the United States based on hospital volume, 2007 to 2011. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1686–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah N, Agarwal V, Patel N, Deshmukh A, Chothani A, Garg J, Badheka A, Martinez M, Islam N, Freudenberger R. National Trends in Utilization, Mortality, Complications, and Cost of Care After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation From 2005 to 2011. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bojikian KD, Chen CL, Wen JC, Zhang Q, Xin C, Gupta D, Mudumbai RC, Johnstone MA, Wang RK, Chen PP. Optic Disc Perfusion in Primary Open Angle and Normal Tension Glaucoma Eyes Using Optical Coherence Tomography-Based Microangiography. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris A, Chung HS, Ciulla TA, Kagemann L. Progress in measurement of ocular blood flow and relevance to our understanding of glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:669–687. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galvez-Ruiz A, Schatz P. Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy in a Population of Diabetics From the Middle East With Microvascular Ocular Motor Palsies. J Neuroophthalmol. 2016;36:131–133. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss HE. Retinal Vascular Changes are a Marker for Cerebral Vascular Diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15:40. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0561-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Overview of The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Rockville, MD: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) [Accessed June, 2016]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. Updated June 18th, 2013.

- 18.US Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed June 10, 2016];Consumer Price Index. https://www.bls.gov/ Updated May, 2016.

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bmj. 2007;335:806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuriyan AE, Lam BL. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy secondary to acute primary-angle closure. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1233–1238. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S45372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy D, Rani PK, Jalali S, Rao HL. A study of prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in patients with non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NA-AION) Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30:101–104. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.833262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch GGFD, Freeman JL. Strategies in the multivariate analysis of data from complex surveys. International Statistical Review. 1975;43:59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census Bureau. Population Estimates. [Accessed July 1, 2016]; https://www.census.gov/popest Updated June 23, 2016.

- 24.Johnson LN, Arnold AC. Incidence of nonarteritic and arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Population-based study in the state of Missouri and Los Angeles County, California. J Neuroophthalmol. 1994;14:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hattenhauer MG, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, Grill R, Gray DT. Incidence of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70999-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moster ML. Visual loss after coronary artery bypass surgery. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:453–457. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams EL, Hart WM, Jr, Tempelhoff R. Postoperative ischemic optic neuropathy. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:1018–1029. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199505000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson DM, Vierkant RA, Belongia EA. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. A case-control study of potential risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1403–1407. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160573008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee MS, Grossman D, Arnold AC, Sloan FA. Incidence of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: increased risk among diabetic patients. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:959–963. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakata R, Aihara M, Murata H, Mayama C, Tomidokoro A, Iwase A, Araie M. Contributing factors for progression of visual field loss in normal-tension glaucoma patients with medical treatment. J Glaucoma. 2013;22:250–254. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31823298fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohtake H, Misaki T, Matsunaga Y, Tubota M, Watanabe Y, Shirao Y. Open heart surgery under total extracorporeal circulation in a patient with advanced glaucoma. Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;1:190–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciulla TA, Harris A, Kagemann L, Danis RP, Pratt LM, Chung HS, Weinberger D, Garzozi HJ. Choroidal perfusion perturbations in non-neovascular age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:209–213. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleming AD, Goatman KA, Philip S, Williams GJ, Prescott GJ, Scotland GS, McNamee P, Leese GP, Wykes WN, Sharp PF, Olson JA. The role of haemorrhage and exudate detection in automated grading of diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:706–711. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.149807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karami M, Janghorbani M, Dehghani A, Khaksar K, Kaviani A. Orbital Doppler evaluation of blood flow velocities in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Rev Diabet Stud. 2012;9:104–111. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2012.9.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nandyala SV, Marquez-Lara A, Fineberg SJ, Singh R, Singh K. Incidence and risk factors for perioperative visual loss after spinal fusion. Spine J. 2014;14:1866–1872. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biousse V, Newman NJ. Ischemic Optic Neuropathies. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2428–2436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1413352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danesh-Meyer HV, Levin LA. Glaucoma as a neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35(Suppl 1):S22–S28. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Singh M, Simpkins JW. From the 90's to now: A brief historical perspective on more than two decades of estrogen neuroprotection. Brain Res. 2016;1633:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levin LA, Danesh-Meyer HV. Hypothesis: a venous etiology for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1582–1585. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.11.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houchens RRD, Elixhauser A, Jiang J. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Redesign Final Report, HCUP Method Series Report. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.