Abstract

Despite the huge worldwide diversity of Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae, Ascomycota), only about 22 species have been reported in Korea. Thus, between 2013 and 2015, soil-derived Trichoderma spp. were isolated to reveal the diversity of Korean Trichoderma. Phylogenetic analysis of translation elongation factor 1 alpha gene was used for identification. Among the soil-derived Trichoderma, Trichoderma albolutescens, T. asperelloides, T. orientale, T. spirale, and T. tomentosum have not been previously reported in Korea. Thus, we report the five Trichoderma species as new in Korea with morphological descriptions and images.

Keywords: EF1α, Phylogeny, Taxonomy, Trichoderma

Trichoderma Persoon (= Hypocrea Fr.) is an ecologically influential genus that contains more than 200 species [1]. These species are basically saprophytes, but have various roles in the ecosystem [2]. They can be easily isolated from soil, wood, air, and even from other fungi as mycoparasites [2].

Trichoderma produce a number of secondary metabolites and a variety of enzymes. Their secondary metabolites include antibiotics, which act against fungi and bacteria and can be used as biocontrol agents for pathogens [3,4]. Trichoderma species also produces enzymes that degrade cellulose, hemicellulose, or chitin. The extracellular enzymes from some Trichoderma species, such as the cellulases from T. reesei E. G. Simmons, have been used for industrial applications [5].

Despite the huge diversity of the genus Trichoderma, the reported diversity of Trichoderma is limited to about 22 species in Korea [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Among them, 11 species of Trichoderma from the Korea University Culture Collection (KUC; Seoul, Republic of Korea) were identified in a previous study [10]. However, the study was limited to wood-derived Trichoderma and was not able to fully explore the diversity of Korean Trichoderma spp. Thus, an investigation of soil-derived Trichoderma was needed.

The aims of this study were to collect indigenous soil-derived Trichoderma and report previously unrecorded species of the same in Korea. A phylogenetic tree of Trichoderma spp. based on the translation elongation factor 1 alpha gene (EF1α) sequences was constructed to classify the collected species. Morphological observations of the macro- and microscopic characteristics were performed to describe the unrecorded Trichoderma spp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of soil-derived Trichoderma cultures.

Seven soil samples were collected from three sites: a fir forest in Odaesan National Park, Republic of Korea (37°44'08.3'' N, 128°35'23.3'' E; in Jan, Apr, Jul, and Oct 2013); Hinoki cypress forest in Jangseong-gun, Jeolanam-do, Republic of Korea (35°22'40.5'' N, 126°44'35.5'' E; in Jun 2013); and a wetland beside the Han River in Seoul, Republic of Korea (37°35'13.8'' N, 126°49'03.4'' E; on 19 Feb 2014).

To isolate fungal cultures, soil solutions (1/1,000) were made from each soil sample and sterilized distilled water (DW) with serial dilution. For each soil sample, 1 µL of diluted soil solution was inoculated onto a 90 mm-plate containing malt extract agar (malt extract 20 g, agar 15 g, DW 1 L; Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) with 0.01% streptomycin sulfate for prevention of bacterial contamination. Recognizable fungal colonies were transferred onto new malt extract agar plates until pure cultures were obtained. Trichoderma spp. were selected based on the morphology of colonies, and collected Trichoderma cultures were deposited in KUC.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Genomic DNA of collected Trichoderma spp. was extracted with an AccuPrep Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea) according to the manufacturer's protocol. PCR amplification of the EF1α region was performed with primers EF1-728F (5′-CAT CGA GAA GTT CGA GAA GG-3′) [12] and TEF1 rev (5′-GCC ATC CTT GGA GAT ACC AGC-3′) [13] according to a previously described method [10]. DNA sequencing was performed using the Sanger method with a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA) by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea).

The obtained EF1α sequences were proofread and aligned with the selected reference sequences from GenBank using MAFFT 7.130 [14] and modified manually with MacClade 4.08 [15]. Datasets were tested by MrModeltest 2.3 using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) with default options [16]. The GTR + I + G model was chosen under the AIC criteria as a result of the test. Bayesian analysis was performed with MrBayes 3.2.1 [17]. The phylogenetic tree was created according to previously described methods [18].

Analysis of phenotype.

Cultures were grown on 9-cm plastic Petri dishes contained 20 mL of corn meal dextrose agar (CMD; cornmeal 20 g, glucose 20 g, agar 18 g, DW 1 L), potato dextrose agar (PDA; potato dextrose agar 39 g, DW 1 L; Difco), or synthetic nitrogen-poor or nutrient-poor agar (SNA; sucrose 0.2 g, glucose 0.2 g, KNO3 1 g, KH2PO4 1 g, MgSO4·7H2O 0.5 g, NaCl 0.5 g, agar 12 g, DW 1 L). To analyze colony characteristics, a 6-mm inoculum plug was placed at about 1.5 cm from the edge of the Petri dish. The cultures were grown at room temperature (20–25℃) [10]. After 1 wk, pictures of colonies were taken using a NEX-5R digital camera (Sony, Tokyo, Japan). The observations were carried out for 15–20 days of growth. The Munsell color system was used for color standards [19]. Morphological analyses of microscopic characteristics were performed with an Olympus BX51 light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Photographs of conidiophores and conidia were taken using the same microscope mounted with an Olympus DP20 microscopic camera, and measurements were made using 3% KOH mounts. At least 30 units of each parameter were measured for each collection. To ensure reliable data, 5% of the measurements from each end of the range were removed. The isolates were deposited at the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR; Incheon, Korea).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation and identification of soil-derived Trichoderma spp.

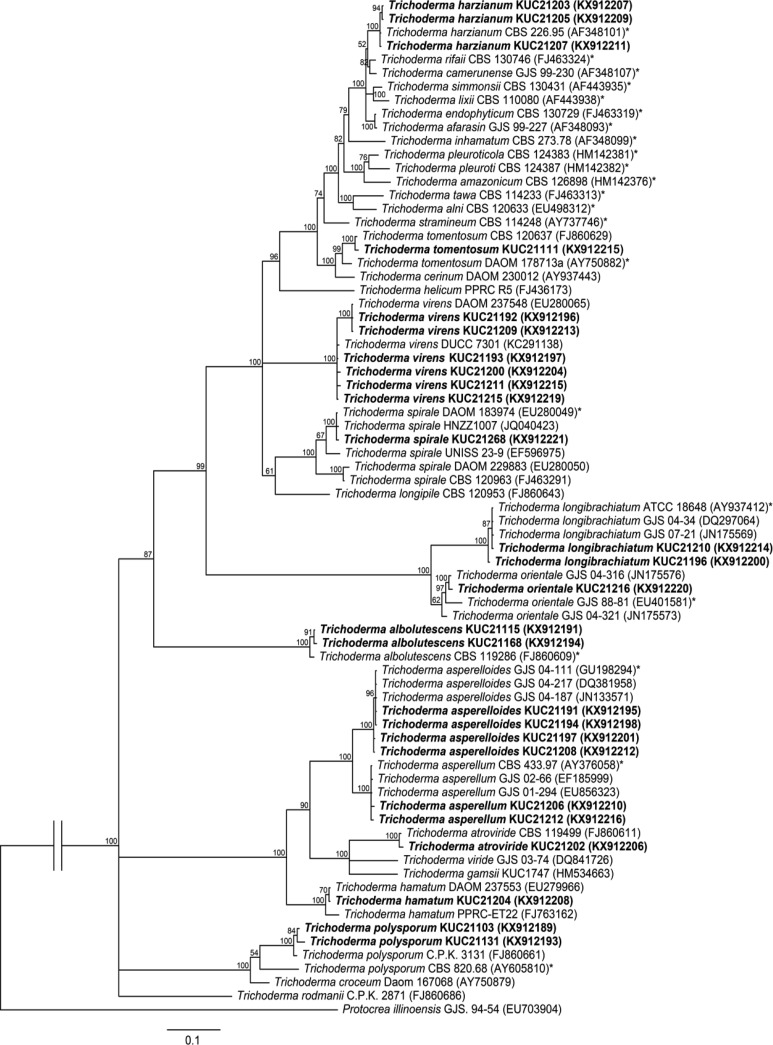

A total of 26 Trichoderma cultures were isolated (Table 1). The Trichoderma spp. were identified by phylogenetic analysis based on the EF1α region (Fig. 1), and the tree obtained was similar to that of other studies [20,21,22,23]. The sequences in the phylogenetic tree were classified into five subgroups: Harzianum, Strictipilosa, Longibrachiatum, Pachybrasioides, Brevicompactum, and Viride-Kongingii group; however, three species: T. helicum Bissett, C. P. Kubicek & Szakács; T. virens (J. H. Mill., Giddens & A. A. Foster) Arx; and T. albolutescens had a single clade [20,21]. Our Trichoderma isolates were identified as 12 species with their own species clade in the phylogenetic tree. Three isolates, KUC21203, KUC20205, and KUC21207, were in a clade with an ex-type strain of T. harzianum Rifai with 100% posterior probabilities (PP). Six isolates were identified as T. virens (= H. virens) with high PP (100%). KUC21196 and KUC21210 were identified as an ex-type strain of T. longibrachiatum Rifai (= H. sagamiensis) with 100% of PP. KUC21103 and KUC21131 were placed into a monophyletic clade with T. polysporum (Link) Rifai (= H. pachybasioides) with 54% PP. KUC21206 and KUC21212 were identified as T. asperellum Samuels, Lieckf. & Nirenberg with 100% PP. KUC21204 was in a clade with T. hamatum (Bonord.) Bainier and 100% PP. The remaining five species, Trichoderma albolutescens, T. asperelloides, T. orientale, T. spirale, and T. tomentosum, have not previously been reported in Korea. For this first report, they are described with macro- and micro observations.

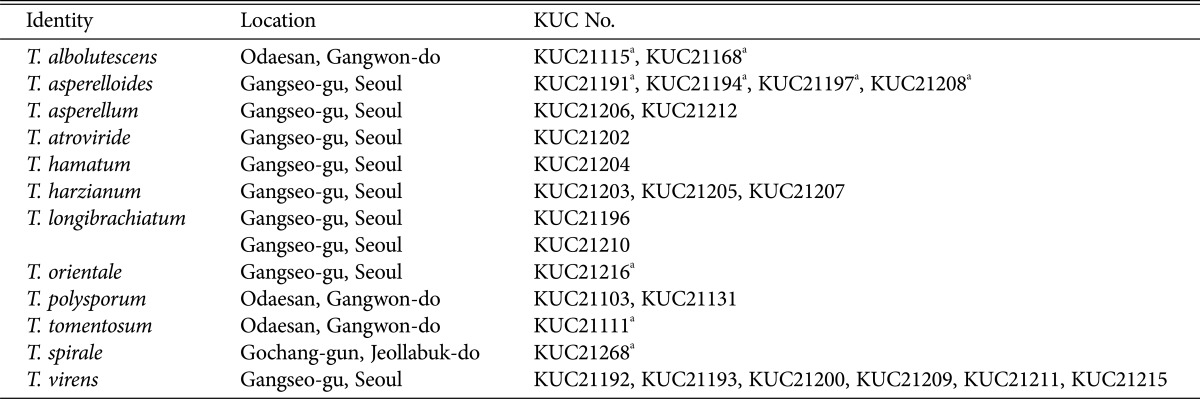

Table 1. Identification of Trichoderma spp. which collected from soil in Korea and their culture numbers.

aNew record species in Korea.

Fig. 1. The 50% majority-rule consensus tree which contains 75 taxa and 785 characters obtained from the bayesian analysis based on the translation elongation factor 1 alpha gene. Numbers above branches indicate posterior probabilities. Fungal cultures examined in this study are in bold. Sequences of type specimens are indicated by asterisk symbols (*).

To the best of our knowledge, including these five new records, 27 species of Trichoderma have been reported in Korea to date [6,7,8,9,10,11]. However, we presume that the diversity of Korean Trichoderma is greater than 100 species, because this study of only three sites revealed five unrecorded species. Further studies throughout the Republic of Korea are required to understand the potential diversity of Trichoderma.

Taxonomy.

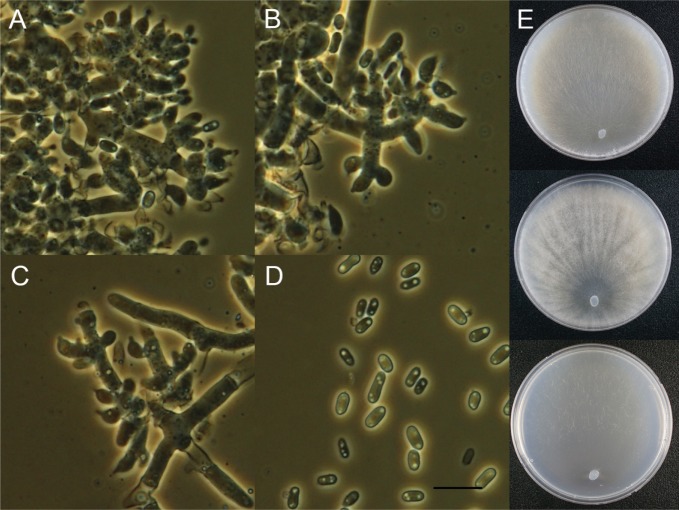

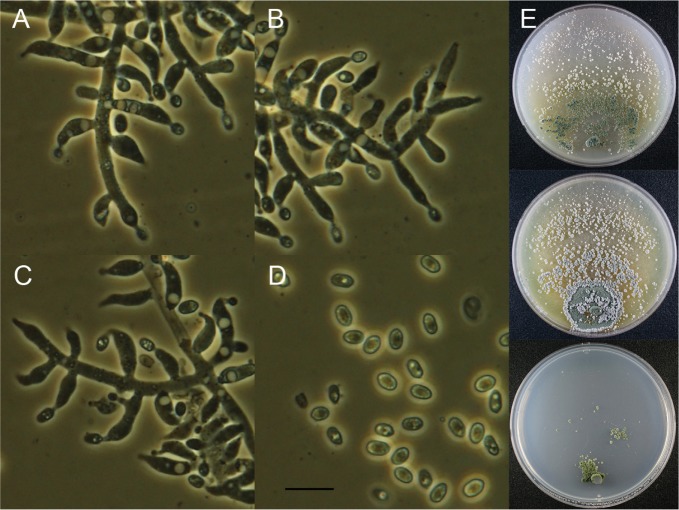

Trichoderma albolutescens Jaklitsch, Fungal Divers. 48: 202 (2011) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Macroscopic and microscopic features of Trichoderma albolutescens KUC21115. A–C, Conidiophore; D, Conidia (scale bar = 10 µm); E, Colonies on corn meal dextrose agar (top), potato dextrose agar (middle), and synthetic nitrogen-poor or nutrient-poor agar (bottom).

Colonies on CMD colony sterile, circular, hyaline at first, turned white to pale orange yellow (10YR9/2) color after 1 wk aerial mycelium abundant, no distinct odor. On PDA colony sterile, circular, thin, zonate, hairy, aerial mycelium abundant, white to light gray (10YR7/2), odor slightly like mushrooms. On SNA hyaline, forming white cottony spots; margin hairy; no pigment, no distinct odor. Conidiation capricious, after 1 wk; compact, white pustules 1–3 mm diameter. Conidiophores with complex, mostly symmetric, often distinctly rectangular branching. Phialides (3.5–)4.0–7.5(–8) × (2–)2.5–3.5(–4.5) µm, (1.5–)2–3(–4) µm wide at the base, ampulliform, short, mostly inequilateral or curved upwards. Conidia (3.2–)3.5–5(–5.7) × (1.6–)1.8–2.5 µm, hyaline, oblong or cylindrical.

Specimens examined: Republic of Korea, Gangwon-do, Pyoengchang-gun, Odaesan National Park, 37°44'08.3'' N, 128°35'23.3'' E, topsoil of fir forest, Apr 2013, Seokyoon Jang (KUC21115, GenBank KX912191); Oct 2013, Seokyoon Jang (KUC21168, GenBank KX912194).

Known distribution: Austria, Germany [21], Spain [24], Republic of Korea.

Note: This species has sterile and greyish to greyish-brown colonies with white cottony mycelia. It is easily distinguishable from other Korean Trichoderm spp. with its green spores. It cannot grow at temperatures over 30℃. KUC21115, KUC21168, and T. albolutescens CBS 119286 are monophyletic with high PPs (100% of PP) in our phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1).

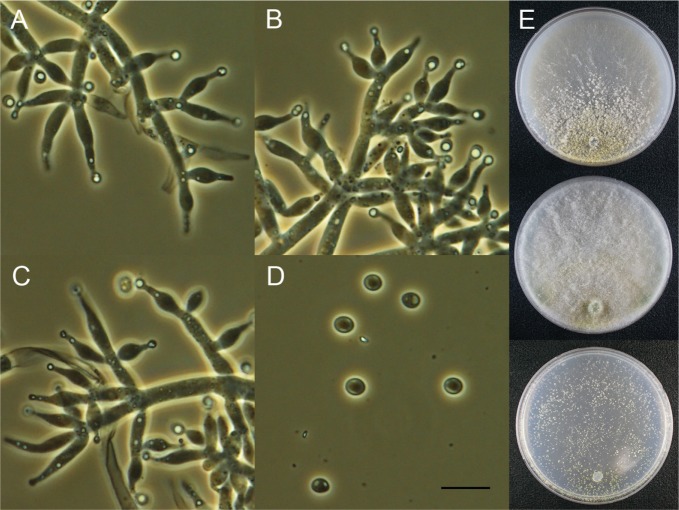

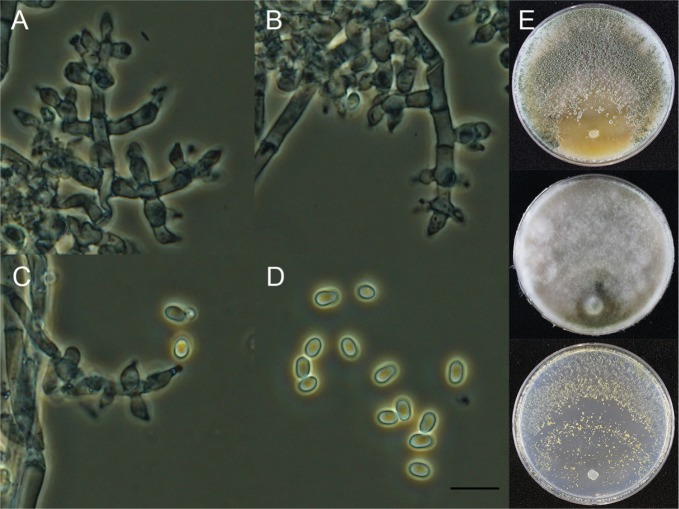

Trichoderma asperelloides Samuels, Mycologia 102: 961 (2010) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Macroscopic and microscopic features of Trichoderma asperelloides KUC21197. A–C, Conidiophore; D, Conidia (scale bar = 10 µm); E, Colonies on corn meal dextrose agar (top), potato dextrose agar (middle), and synthetic nitrogen-poor or nutrient-poor agar (bottom).

Colonies on CMD conidiophores produced in pustules, conidia pale yellow (5Y8/4) to yellow (7Y7/8). On PDA conidiophores produced in pustules, aerial mycelium abundant, conidia pale yellow (5Y8/4) to yellowish green (5GY6/4), no distinctive odor or diffusing pigment. Colonies on SNA abundant conidia formation, scattered, 1–1.5 mm diameter pustules, no distinctive odor or pigment observed, pustules yellow (7Y7/8) to yellowish green (5GY6/4). Conidiophores smooth central axis from which secondary branches arise, secondary branches tending to be paired but also commonly asymmetric, all branches terminating in a single phialide or a whorl of 2–4 divergent phialides. Phialides 5–10.5 µm long, (2–)2.5–3.5 µm at the widest, 1–2.5(–3) µm wide at the base, flask-shaped. Conidia dark green, subglobose, 3.5–4.5(–5) × 3–3.9 µm.

Specimens examined: Republic of Korea, Seoul, 37°35'13.8'' N, 126°49'03.4'' E, soil of wetland beside Han River, 19 Feb 2014, Seokyoon Jang (KUC21191, GenBank KX912195; KUC21194, GenBank KX912198; KUC21197, GenBank KX912201; KUC21208, GenBank KX912212).

Known distribution: China [24], Korea.

Note: Morphologically, this species is very similar to and indistinguishable from T. asperellum [24]. Moreover, our isolates of T. asperellum and T. asperelloides were isolated from same source. On the other hand, they are clearly separated into two clades with high support (100% PP) in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). Molecular biological approaches are necessary to identify these two species.

Trichoderma orientale (Samuels & Petrini) Jaklitsch & Samuels, Mycotaxon 126: 151 (2014) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Macroscopic and microscopic features of Trichoderma orientale KUC21216. A–C, Conidiophore; D, Conidia (scale bar = 10 µm); E, Colonies on corn meal dextrose agar (top), potato dextrose agar (middle), and synthetic nitrogen-poor or nutrient-poor agar (bottom).

Colonies on CMD with few aerial mycelium, conidial production forming in broad concentric rings, light greenish gray (10GY7/1) to dark grayish green (10GY4/2); diffusing pale yellow (5Y8/3) to olive yellow (5Y6/6) pigment. On PDA aerial mycelium uniformly cottony, conidial production forming in broad concentric rings, light greenish gray (10GY7/1) to dark greenish gray (5G4/2); no distinctive odor, diffusing pale yellow (5Y8/3) to olive yellow (5Y6/6) pigment. Colonies on SNA conidia forming in abundant, scattered, 1–1.5 mm diameter pustules, light olive green (10Y6/2) to dark olive green (5GY3/4); no distinctive odor or pigment. Conidiophores primary branches tending to produce phialides singly, either directly from the branch itself or terminating a short secondary branch. Phialides typically not held in whorls. Phialides typically cylindrical, straight, (5.5–)7–12 µm long, (1.5–)2–4(–4.5) µm at the widest, 1.5–3 µm at the base. Conidia oblong to ellipsoidal, 3.5–4.5 × 2.4–3 µm, smooth. Chlamydospores not observed.

Specimens examined: Republic of Korea, Seoul, 37°35'13.8'' N, 126°49'03.4'' E, soil of wetland beside Han River, 19 Feb 2014, Seokyoon Jang (KUC21216, GenBank KX912220).

Known distribution: China, New Zealand, South Africa [25], Ecuador, Spain [22], Korea.

Note: Trichoderma orientale KUC21216 matched the protologue description well, except for the protologue conidia being longer (4.0–)5.0–7.2(–10.5) µm [25]. This may be an intraspecies variation because we analyzed a single Korean T. orientale strain. To investigate this feature, other Korean strains need to be studies. KUC21216 and the type strain of T. orientale (GJS 88-81) are monophyletic with high support (97% PP) (Fig. 1).

Trichoderma spirale Bissett, Can. J. Bot. 69: 2408 (1991) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Macroscopic and microscopic features of Trichoderma spirale KUC21268. A–C, Conidiophore; D, Conidia (scale bar = 10 µm); E, Colonies on corn meal dextrose agar (top), potato dextrose agar (middle), and synthetic nitrogen-poor or nutrient-poor agar (bottom).

Colonies on CMD forming a few aerial mycelium, conidial production forming in broad concentric rings, very dark grayish green (5GY3/2); olive-coloured pigment (5Y4/3). On PDA aerial mycelium abundant, conidial production forming in broad concentric rings, grayish green (5GY5/2) to dark grayish green (5GY4/2); olive yellow pigment (2.5Y6/8). Colonies on SNA conidia forming in abundant, scattered, 1–2 mm diam pustules; dark grayish green (5GY4/2); no distinctive pigment. No distinctive odor. Conidiophores broad fertile branches arising from the base. The secondary branches arising from the fertile branches, containing 1–2 cells. Phialides arising in dense clusters, nearly doliiform, short, (3.7–)4–6.4(–7.4) µm long, 2.6–3.5(–4.3) µm widest, 1.9–2.8(–3.2) µm wide at the base. Conidia smooth, oblong to ellipsoidal, 4.1–5.1 × 2.5–2.8(–3) µm. Chlamydospores not observed.

Specimens examined: Republic of Korea, Jeollanam-do, Jangseong-gun, 35°22'40.5'' N, 126°44'35.5'' E, topsoil of Hinoki cypress forest, June 2013, Seokyoon Jang (KUC21268, GenBank KX912221).

Known distribution: Cosmopolitan [26].

Note: Trichoderma spirale KUC21268 matched well with the descriptions in the other study [26]. KUC21268 and a type strain of T. spirale (DAOM 183974) are monophyletic with high support (100% PP) (Fig. 1).

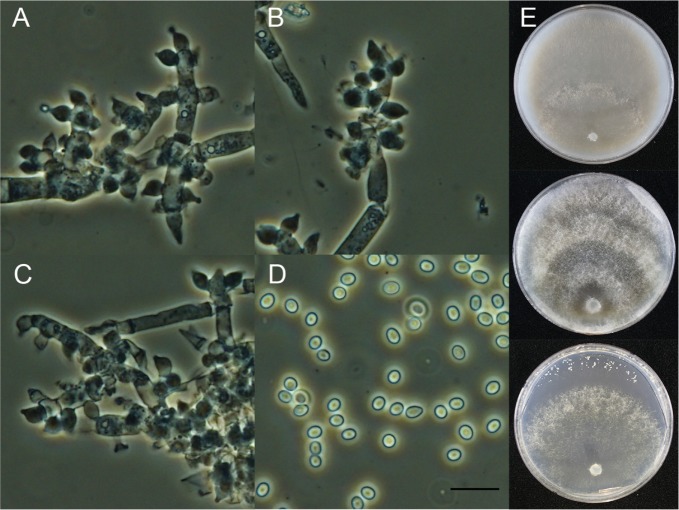

Trichoderma tomentosum Bissett, Can. J. Bot. 69: 2412 (1991) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Macroscopic and microscopic features of Trichoderma tomentosum KUC21211. A–C, Conidiophore; D, Conidia (scale bar = 10 µm); E, Colonies on corn meal dextrose agar (top), potato dextrose agar (middle), and synthetic nitrogen-poor or nutrient-poor agar (bottom).

Colonies on CMD conidiophores forming pustules in circular around the edge of the colony, aerial mycelium abundant, pustules 0.5–1 mm diam., light grayish green (5GY6/2) to grayish green (5GY5/2); no distinctive odor or pigment. On PDA aerial mycelium uniformly cottony, conidial production forming in broad concentric rings, pale olive (10Y6/4); no distinctive odor or pigment. Colonies on SNA conidiophores forming pustules in circular around the edge of the colony, scattered, 1–2mm diam pustules dark grayish green (5GY4/2); no distinctive odor or pigment. Phialides ampulliform with a distinct neck, mostly curved upwards short, (3.9–)4.2–5.6(–5.8) µm long, (2.7–)3–3.7(–4.3) µm at the widest, (1.7–)2–2.7(–3) µm at the base. Conidia smooth, broadly ellipsoidal, (2.8–)3–3.3(–3.6) × 2.3–2.7 µm. Chlamydospores not observed.

Specimens examined : Republic of Korea, Gangwon-do, Pyoengchang-gun, Odaesan National Park, 37°44'08.3'' N, 128°35'23.3'' E, topsoil of fir forest, Apr 2013, Seokyoon Jang (KUC21111, GenBank KX912190).

Known distribution: Cosmopolitan [20,26,27,28].

Note: Trichoderma tomentosum KUC21111 matched well with the other previous description [26]. It cannot grow at temperatures over 35℃. KUC21111 and a type strain of T. tomentosum (DAOM 178713a) are grouped with a monophyletic clade (99% of PP) (Fig. 1).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was also supported by the project on survey and excavation of Korean indigenous species of National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR) under the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Yabuki T, Miyazaki K, Okuda T. Japanese species of the Longibrachiatum clade of Trichoderma. Mycoscience. 2014;55:196–212. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Druzhinina IS, Seidl-Seiboth V, Herrera-Estrella A, Horwitz BA, Kenerley CM, Monte E, Mukherjee PK, Zeilinger S, Grigoriev IV, Kubicek CP. Trichoderma: the genomics of opportunistic success. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:749–759. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harman GE, Howell CR, Viterbo A, Chet I, Lorito M. Trichoderma species: opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong JH, Lee J, Min M, Ryu SM, Lee D, Kim GH, Kim JJ. 6-Pentyl-α-pyrone as an anti-sapstain compound produced by Trichoderma gamsii KUC1747 inhibits the germination of ophiostomatoid fungi. Holzforschung. 2014;68:769–774. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Crom S, Schackwitz W, Pennacchio L, Magnuson JK, Culley DE, Collett JR, Martin J, Druzhinina IS, Mathis H, Monot F, et al. Tracking the roots of cellulase hyperproduction by the fungus Trichoderma reesei using massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16151–16156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905848106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Hong SB, Kim CY. Contribution to the checklist of soil-inhabiting fungi in Korea. Mycobiology. 2003;31:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park MS, Seo GS, Bae KS, Yu SH. Characterization of Trichoderma spp. associated with green mold of Oyster mushroom by PCR-RFLP and sequence analysis of ITS regions of rDNA. Plant Pathol J. 2005;21:229–236. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park MS, Bae KS, Yu SH. Two new species of Trichoderma associated with green mold of oyster mushroom cultivation in Korea. Mycobiology. 2006;34:111–113. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2006.34.3.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho H, Miyamoto T, Takahashi K, Hong S, Kim J. Damage to Abies koreana seeds by soil-borne fungi on Mount Halla, Korea. Can J Forest Res. 2007;37:371–382. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huh N, Jang Y, Lee J, Kim GH, Kim JJ. Phylogenetic analysis of major molds inhabiting woods and their discoloration characteristics Part 1. Genus Trichoderma. Holzforschung. 2011;65:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SY, Jung HY, Lee HB, Kim SH, Shin KS, Eom AH, Kim C, Lee SY. National list of species of Korea: Ascomycota, Glomeromycota, Zygomycota, Myxomycota, Oomycota. Incheon: National Institute of Biological Resources; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbone I, Kohn LM. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous Ascomycetes. Mycologia. 1999;91:553–556. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuels GJ, Dodd SL, Gams W, Castlebury LA, Petrini O. Trichoderma species associated with the green mold epidemic of commercially grown Agaricus bisporus. Mycologia. 2002;94:146–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maddison DR, Maddison WP. MacClade 4: analysis of phylogeny and character evolution. Version 4.08. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nylander JA. MrModeltest v2. Program distributed by the author. Uppsala: Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong JH, Jang S, Heo YM, Min M, Lee H, Lee YM, Lee H, Kim JJ. Investigation of marine-derived fungal diversity and their exploitable biological activities. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:4137–4155. doi: 10.3390/md13074137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munsell Color. Munsell soil color charts with genuine Munsell color chips. Grand Rapids (MI): Munsell Color; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaklitsch WM. European species of Hypocrea Part I. The green-spored species. Stud Mycol. 2009;63:1–91. doi: 10.3114/sim.2009.63.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaklitsch WM. European species of Hypocrea part II: species with hyaline ascospores. Fungal Divers. 2011;48:1–250. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0088-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaklitsch WM, Voglmayr H. Biodiversity of Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae) in Southern Europe and Macaronesia. Stud Mycol. 2015;80:1–87. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaverri P, Branco-Rocha F, Jaklitsch W, Gazis R, Degenkolb T, Samuels GJ. Systematics of the Trichoderma harzianum species complex and the re-identification of commercial biocontrol strains. Mycologia. 2015;107:558–590. doi: 10.3852/14-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuels GJ, Ismaiel A, Bon MC, De Respinis S, Petrini O. Trichoderma asperellum sensu lato consists of two cryptic species. Mycologia. 2010;102:944–966. doi: 10.3852/09-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuels GJ, Petrini O, Kuhls K, Lieckfeldt E, Kubicek CP. The Hypocrea schweinitzii complex and Trichoderma sect. Longibrachiatum. Stud Mycol. 1998;41:1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaverri P, Castlebury LA, Overton BE, Samuels GJ. Hypocrea/Trichoderma: species with conidiophore elongations and green conidia. Mycologia. 2003;95:1100–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoyos-Carvajal L, Orduz S, Bissett J. Genetic and metabolic biodiversity of Trichoderma from Colombia and adjacent neotropic regions. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46:615–631. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun RY, Liu ZC, Fu K, Fan L, Chen J. Trichoderma biodiversity in China. J Appl Genet. 2012;53:343–354. doi: 10.1007/s13353-012-0093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]