Abstract

Successful embryonic development is dependent on factors secreted by the reproductive tract. Dickkopf-1 (DKK1), an antagonist of the wingless-related mouse mammary tumor virus (WNT) signaling pathway, is one endometrial secretory protein potentially involved in maternal-embryo communication. The purpose of this study was to investigate the roles of DKK1 in embryo cell fate decisions and competence to establish pregnancy. Using in vitro-produced bovine embryos, we demonstrate that exposure of embryos to DKK1 during the period of morula to blastocyst transition (between d 5 and 8 of development) promotes the first 2 cell fate decisions leading to increased differentiation of cells toward the trophectoderm and hypoblast lineages compared with that for control embryos treated with vehicle. Moreover, treatment of embryos with DKK1 or colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2; an endometrial cytokine known to improve embryo development and pregnancy establishment) between d 5 and 7 of development improves embryo survival after transfer to recipients. Pregnancy success at d 32 of gestation was 27% for cows receiving control embryos treated with vehicle, 41% for cows receiving embryos treated with DKK1, and 39% for cows receiving embryos treated with CSF2. These novel findings represent the first evidence of a role for maternally derived WNT regulators during this period and could lead to improvements in assisted reproductive technologies.—Denicol, A. C., Block, J., Kelley, D. E., Pohler, K. G., Dobbs, K. B., Mortensen, C. J., Ortega, M. S., Hansen, P. J. The WNT signaling antagonist Dickkopf-1 directs lineage commitment and promotes survival of the preimplantation embryo.

Keywords: embryo development, cell differentiation, pregnancy

Although genetically programmed, the process of preimplantation embryonic development is dependent on regulatory signals from the reproductive tract of the mother. Development of the preimplantation embryo outside the reproductive tract results in embryos that are aberrant with respect to morphology, allocation of cells between the inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE), gene expression, and competence to survive after transfer to the uterus (1–6). The nature of the regulatory molecules produced by the uterus and their mechanism of action are not well understood. Among the molecules implicated in maternal regulation of embryonic development are colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), epidermal growth factor (EGF), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2), and activin-A (7–11).

The wingless-related mouse mammary tumor viruses (WNTs) are members of another family of regulatory molecules that could be important for maternal regulation of preimplantation development. The reproductive tract produces WNTs and regulators of WNT signaling (12–15). In the endometrium, the WNT signaling pathway is regulated by sex steroids (16–19). The embryo is another source of WNTs: the morula-stage bovine embryo, for example, expresses ≥15 WNT genes (20). Consequences of WNT regulation for embryonic development are unclear, with reports indicating that activation of canonical WNT signaling either improves (21), reduces (20–22), or has no effect (23) on the proportion of embryos that can develop to the blastocyst stage. In the mouse, for example, inhibition of WNT signaling did not affect the proportion of embryos that developed to the blastocyst stage but decreased blastocyst activation and implantation (23). In the cow, activation of canonical WNT signaling reduced the competence of the embryo to develop to the blastocyst stage and the resultant blastocysts had reduced cell numbers, particularly for TE cells (20). Activation of WNT signaling in pig embryos reduced total cell and TE numbers in the blastocyst and the ability of blastocysts to hatch from the zona pellucida (22).

One function of canonical WNT signaling in the embryo is regulation of pluripotency (24, 25). An important role for the maternal regulatory system during early pregnancy may be to facilitate differentiation by acting as a brake to canonical WNT signaling. Dickkopf-1 (DKK1), an inhibitor of canonical WNT signaling, is produced by the endometrium during the menstrual and estrous cycles and early pregnancy (13, 15, 26–29). A variation in the regulation of WNT signaling by maternal DKK1 may be an important determinant of the survival of the embryo. Endometrial expression of DKK1 is reduced among heifers that are inherently infertile (29) and in cows during lactation (28), a physiological condition that reduces endometrial support for embryonic development (30).

Here we tested the hypothesis that DKK1 promotes the ability of blastomeres of the preimplantation embryo to undergo the first 2 differentiation events: formation of the TE and hypoblast. This hypothesis was tested by evaluating the proportion of cells in the blastocyst that differentiate into TE and hypoblast. Cell lineages in the blastocyst were assessed by evaluating the localization of transcription factors important for differentiation of the TE [caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2); ref. 31] and hypoblast [GATA binding protein 6 (GATA6); ref. 32] and for maintenance of pluripotency in the ICM [Nanog homeobox (NANOG); ref. 33]. Moreover, we tested whether the actions of DKK1 on the embryo exert long-term effects on the trajectory of development so that the embryo is better able to establish and maintain pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro production of embryos for experiments on differentiation

Embryos were produced in vitro using slaughterhouse-derived oocytes. Procedures for production of embryos were described previously (34) except for in vitro fertilization. Sperm from frozen-thawed straws of 3 randomly selected bulls was purified using a gradient of ISolate Separation Medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA). A different set of bulls was used for each replicate. Fertilization of matured oocytes was performed in 35-mm Petri dishes using 1700 μl of synthetic oviductal fluid for fertilization (SOF-FERT) medium (35) and up to 250 cumulus-oocyte complexes per dish. The final concentration of sperm in the fertilization dishes was 1 × 106/ml. A solution of PHE [80 μl of 1 mM hypotaurine, 2 mM penicillamine, and 250 μM epinephrine in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl as described by Bonilla et al. (10)] was also added to the medium to stimulate capacitation of sperm. Fertilization conditions were 8–10 h, 38.5°C, and a humidified atmosphere of 5% (v/v) CO2. At the end of the fertilization period, presumptive zygotes were washed in HEPES-SOF medium [10 mM HEPES, 1.17 mM CaCl2, 0.49 mM MgCl2, 1.19 mM KH2PO4, 7.16 mM KCl, 107.7 mM NaCl, 2.0 mM NaHCO3, 5.3 mM sodium lactate, 0.02 mM sodium pyruvate, 3 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 7.5 μg/ml gentamicin] and randomly placed in groups of 25–30 putative zygotes in 45-μl microdrops of SOF-bovine embryo 1 (BE1) (36) covered in mineral oil (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Embryos were cultured at 38.5°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% (v/v) O2, 5% (v/v) CO2, and the balance N2.

The cleavage rate was assessed at d 3 of development (d 0 = day of fertilization). At d 5, each microdrop of embryos was supplemented with either 5 μl of vehicle [Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA] or 1000 ng/ml recombinant human DKK1 (to achieve a final concentration of 100 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The concentration of DKK1 was chosen because it blocks the actions of a canonical WNT agonist on development of bovine blastocysts (20).

Actions of DKK1 to regulate lineage commitment in the blastocyst

Embryos were treated at d 5 with either vehicle or DKK1. Blastocysts were harvested at d 7 and 8 of development and analyzed using immunofluorescence procedures to determine the absolute and relative numbers of cells labeling with antibodies to CDX2 (TE), GATA6 (hypoblast), and NANOG (epiblast). The experiment was repeated on a total of 8 different occasions (i.e., replicates) with 131 control and 161 DKK1-treated blastocysts being subjected to analysis by immunofluorescence.

For 4 replicates, embryos were examined for immunolocalization of GATA6 and CDX2. The antibody dilution buffer consisted of DPBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 and 1% (w/v) BSA, and the wash buffer consisted of DPBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 0.1% (w/v) BSA. Harvested blastocysts were washed 3 times in cold DPBS containing 0.2% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in DBPS/PVP for 15 min, and washed in DPBS/PVP. Embryos were incubated in permeabilization solution [DPBS containing 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100] for 30 min, followed immediately by a 1-h incubation in blocking buffer [DPBS containing 5% (w/v) BSA]. Embryos were next incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg/ml rabbit anti-human polyclonal GATA6 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), washed 6 times in wash buffer, and incubated with 1 μg/ml goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h in the dark. Embryos were washed 6 times in wash buffer and incubated for 1 h with mouse anti-human polyclonal CDX2 antibody, ready to use (Biogenex, Fremont, CA, USA), followed by 6 washes in wash buffer and incubation with 1 μg/ml goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) in the dark. Embryos were again washed 6 times in wash buffer. Nuclear labeling was achieved using Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/ml in DPBS/PVP) for 15 min in the dark. Embryos were finally rinsed in DPBS/PVP and placed on a slide containing 1 drop of SlowFade Gold antifade reagent (Life Technologies), covered with a coverslip, and observed with a ×40 objective using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) and Zeiss filter sets 02 [4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)], 03 (FITC), and 04 (rhodamine). Digital images were acquired using AxioVision software (Zeiss) and a high-resolution black and white Zeiss AxioCam MRm digital camera. For control groups, the primary antibodies were replaced with IgG from the species in which the primary antibody was raised. For evaluation of total cells and CDX2+ cells, a total of 197 blastocysts were evaluated (87 d 7 embryos and 110 d 8 embryos). For analysis of GATA6+ cells in the ICM, 269 blastocysts were evaluated (80 d 7 embryos and 189 d 8 embryos). For analysis of total GATA6+ cells and GATA6+ in the TE, 179 blastocysts were evaluated (80 d 7 embryos and 99 d 8 embryos).

For 4 replicates, embryos were examined for immunolocalization of GATA6, NANOG, and CDX2. The protocol was performed as described above except that different antibodies were used. The first antibody pair was 1 μg/ml rabbit anti-human polyclonal GATA6 antibody and 1 μg/ml goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555. The second set of antibodies was 1 μg/ml mouse anti-human polyclonal NANOG antibody (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) and 1 μg/ml goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC. The third antibody set was mouse anti-human polyclonal CDX2 antibody, ready to use, and 1 μg/ml goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 350 (Life Technologies). Procedures were the same as those described above. The experiment involved a total of 90 blastocysts at d 8 of development. Counting of cells of the different lineages was performed using the cell count function of ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). All cell counting was performed by one examiner; cells were counted in a subset of embryos by a second, blind examiner. Agreement between examiners was 95%.

Selected embryos were examined by confocal microscopy. Embryos were observed at ×20 and ×60 using an Olympus IX2-DSU spinning disc confocal fluorescent microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a Semrock BrightLine Sedat filter set band 1/4 for DAPI, band 2/4 for FITC, and band 3/4 for tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate. Embryos from both immunolocalization procedures (GATA6/CDX2 and GATA6/NANOG/CDX2) were evaluated, and images were acquired using a Hamamatsu ORCA-AG camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, K.K., Hamamatsu City, Japan) and 3i SlideBook v4.2 software with a deconvolution module (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc., Denver, CO, USA). Images were obtained in 5-μm sections.

Actions of DKK1 and CSF2 to improve competence of blastocysts to survive after transfer to recipients

The objective was to determine whether embryos treated with DKK1 had increased competence to establish and maintain pregnancy when transferred to recipient females. Treatment with CSF2 was used as a positive control because embryos treated with CSF2 had previously been shown to have increased competence to establish and maintain pregnancy after embryo transfer (9).

In vitro production of Holstein embryos for embryo transfer

Holstein oocytes were purchased from 3 different companies: Sexing Technologies (Laceyville, PA, USA), Applied Reproductive Technology (Madison, WI, USA), and Ovitra Biotechnologies (Midway, TX, USA). Oocytes were shipped overnight in maturation medium provided by the companies. On arrival at the laboratory, oocytes were washed in HEPES-SOF and incubated in groups of ∼30 in 50-μl drops of fertilization medium (prepared as described above) covered with mineral oil and containing 1 × 106 X-sorted sperm that had been purified using a Percoll (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) gradient [500 μl of a solution of 45% Percoll (diluted 1:1 in HEPES-SOF) on top of 500 μl of a solution of 90% Percoll] (37). Sperm from a single Holstein bull was used for each replicate; a total of 4 bulls were used. Fertilization proceeded for 10–12 h after which all oocytes (now presumptive zygotes) were washed and placed in 45 μl of SOF-BE1 and cultured as described previously. On d 5 after insemination, drops of embryos received 5 μl of either vehicle [DPBS containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA], 1000 ng/ml DKK1 (to achieve a final concentration of 100 ng/ml), or 100 ng/ml CSF2 (to achieve a final concentration of 10 ng/ml; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland). Blastocysts and, occasionally, morulae were harvested at d 7 after insemination and transferred to recipients. The percentages of transferred embryos that were at the morula stage were 11% (vehicle), 13% (DKK1), and 9% (CSF2). Only embryos classified as 1 or 2 quality grade (38) were transferred.

Embryo transfer

The protocol for care and use of animals was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under protocol number 201106114. Transfers were performed at 2 dairy farms: the University of Florida Dairy Unit and a commercial dairy located 56 km away from the laboratory. The experiment was conducted from May to September 2012. Each week, lactating Holstein cows (>80 d postpartum) undergoing ovulation synchronization as part of the reproductive program of each farm were blocked by parity and randomly assigned to receive an embryo from 1 of the 3 treatments. At d 7 after predicted ovulation, ovaries were examined ultrasonically (Easy Scan; BCF Technology, Livingston, Scotland). Cows with a detectable corpus luteum were selected for transfer. Each cow received 5 ml of 1% (w/v) lidocaine in the epidural space between the last sacral and first coccygeal vertebrae. A fresh embryo was transferred transcervically to the uterine horn ipsilateral to the ovary bearing the corpus luteum using an embryo transfer pipette. Transfers were conducted on a total of 11 occasions with the total number of cows receiving embryos being 71, 85, and 94 for control, DKK1, and CSF2, respectively.

Pregnancy diagnosis was performed using ultrasonography at d 32 of gestation and between d 64 and 76 of gestation, according to the farm's schedule. Cows were considered pregnant at 32 d if an embryo with a heartbeat was detected and at d 64–76 by the presence of a fetus. Cows were observed to determine whether pregnancies proceeded to term.

Analysis of interferon-stimulated gene 15 ubiquitin-like modifier (ISG15) expression in maternal peripheral leukocytes

Blood samples were collected at d 20 of gestation (13 d after embryo transfer) from a subgroup of 75 embryo recipients (n=21 control, 29 DKK1, and 25 CSF2) for analysis of expression of ISG15 in leukocytes. Samples were collected in 10-ml Vacutainer tubes containing EDTA (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and kept on ice until arrival at the laboratory. Samples were centrifuged at 1500 g for 15 min at 4°C. Buffy coats were retrieved and immediately frozen at −80°C in buffer RLT [cell lysis buffer containing guanidine thiocyanate provided as a reagent in the AllPrep DNA/RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA)] containing 1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol until further processing. RNA extraction and isolation were performed using the AllPrep DNA/RNA mini kit. Analysis of the total RNA concentration and quality was performed with a Nanodrop analyzer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by treatment of 10 μl of RNA with 2 U of DNase in 10 μl (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). DNase-treated samples were reverse transcribed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, following the instructions of the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The protocol consisted of incubation of samples and master mix containing random hexamer primers, dNTPs, and reverse transcriptase for 10 min at 25°C, 120 min at 37°C, and 5 min at 85°C. Negative controls were obtained by subjecting the samples to the same protocol without reverse transcriptase. The cDNA was stored at −20°C until further use. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System and SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix with Low ROX (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Each reaction consisted of 1 μl of forward primer (0.5 μM), 1 μl of reverse primer (0.5 μM), 10 μl of EvaGreen Supermix, 6.8 μl of 0.1% (v/v) diethylpyrocarbonate-treated H2O, and 1.2 μl of cDNA sample. The PCR protocol consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s followed by annealing at 95°C for 5 s and extension at 60°C for 5 s. This sequence was repeated for 40 cycles. Melt curve analysis consisted of one cycle of 65 to 95°C with 0.5°C increments every 5 s. Primers for ISG15 were those validated and used by Green et al. (39). The efficiency of amplification was determined using the standard curve method and found to be 100.5%. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene because it was previously used for lymphocytes of pregnant and nonpregnant cows (40). Primers were as follows: forward, 5′-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3′; and reverse, 5′-CAACAGACACGTTGGGAGTG-3′ (41).

After the real-time procedure, Ct values obtained for ISG15 were normalized to GAPDH for each individual animal to generate ΔCt values. For fold change comparisons, the mean ΔCt value of the group of cows receiving a control embryo and diagnosed as nonpregnant was calculated, and ΔΔCt was obtained by subtracting the mean ΔCt from each individual animal's ΔCt. Fold change was calculated by the formula 2−ΔΔCt. Statistical analysis was based on ΔCt values.

Analysis of pregnancy-associated glycoprotein (PAG) and progesterone concentrations in plasma of embryo recipients

Concentrations of PAG and progesterone in plasma were evaluated in a subgroup of 158 embryo recipients at d 32 of gestation. Samples were maintained on ice from collection until arrival at the laboratory, where they were centrifuged at 2000 g for 30 min at 4°C with plasma frozen immediately afterward. Samples were subjected to analysis of PAG concentration using a monoclonal antibody-based ELISA (42). With use of this antibody, concentrations of PAG in nonpregnant cows were <0.5 ng/ml by week 5 postpartum (42); thus, PAGs from the previous pregnancy should not have contributed to observed values. Plasma progesterone concentrations were analyzed using solid-phase radioimmunoassay (Coat-A-Count Progesterone; Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Ultrasonography of embryos at d 34 of gestation

A subgroup of 20 pregnant cows (4 control, 8 DKK1, and 8 CSF2) were subjected to ultrasonography at d 34 of gestation using Doppler ultrasound (MicroMaxx; Sonosite, Bothell, WA, USA) to estimate embryonic crown-to-rump length.

Statistical analysis

SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Data obtained from cultured embryos were subjected to analysis of variance using the generalized linear model procedure (Proc GLM). Replicate was considered a random variable, and treatment was considered fixed in all models. Results are presented as least squares means ± sem. Pregnancy and calving outcomes from the embryo transfer experiment were analyzed using the GLIMMIX generalized linear mixed model procedure and specifying binomial distribution of the response variable. Pregnancy data were also subjected to survival analysis using the LIFETEST procedure. Other variables from this experiment were analyzed by least squares analysis of variance using Proc GLM. For all analyses, orthogonal contrasts were used to separate treatment effects as follows: control vs. DKK1 + CSF2 and DKK1 vs. CSF2. The preplanned comparisons were chosen because both DKK1 and CSF2 (9) were expected to increase the pregnancy rate compared with that for controls. Original models for analysis of pregnancy outcomes included effects of treatment, farm, replicate (week of embryo transfer), and bull. Explanatory variables not having a significant effect on the outcomes were removed from the final analyses. The level of significance used in all analyses was 0.05.

RESULTS

Cleavage rates and blastocyst development in response to DKK1

The effect of DKK1 on the ability of embryos to develop to the blastocyst stage was assessed in 8 replicates involving 1640 presumptive zygotes. By chance, the cleavage rate at d 3 of development tended to be higher (P=0.08) for embryos treated with DKK1 beginning at d 5 (65.8±1.8% for control vs. 71.0±1.8% for DKK1). There was a tendency (P=0.06) for the percentage of oocytes that became a blastocyst at d 7 to be increased by DKK1 (22.5±1.1% for control embryos vs. 26.0±1.1% for DKK1 embryos, respectively). There was no treatment effect on blastocyst development at d 8 (23.4±7.0 vs. 28.8±7.0%). Calculation of blastocyst data as the percentage of cleaved embryos becoming a blastocyst resulted in no effect of DKK1 at d 7 (35.3±1.2 vs. 37.9±1.2%) or d 8 (44.6±2.5 vs. 49.9±2.5%).

Developmental changes in blastocyst differentiation

At d 7 of development, 2 cell populations could be clearly distinguished in bovine blastocysts: ICM (CDX2−) and TE (CDX2+). This pattern was maintained at d 8 of development (Fig. 1). GATA6+ cells were identified within both the ICM and TE, although the intensity of labeling was greater for the ICM than for TE (Fig. 1). At d 8, the labeling intensity of GATA6 in the ICM increased, whereas that in the TE decreased. Brightly labeled GATA6+ cells were limited almost entirely to the ICM (Fig. 2). Moreover, NANOG+ cells (i.e., epiblast precursors) were evident and restricted to the ICM (Figs. 3 and 4). Labeling for GATA6 and NANOG was usually mutually exclusive, although a small percentage of cells in the ICM were positive for both markers (Figs. 3 and 4).

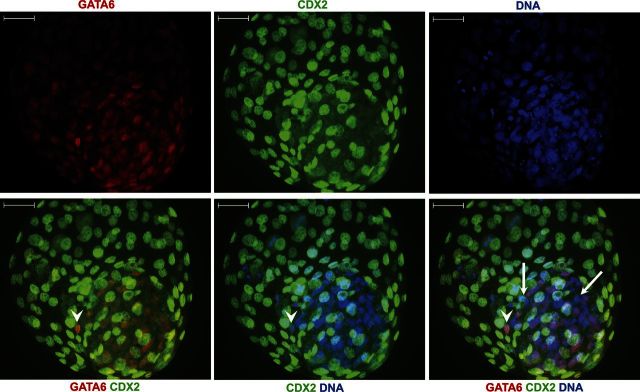

Figure 1.

Immunolocalization of CDX2 and GATA6 in blastocysts at d 8 of development. Hoechst 33342 was used as a nuclear stain for all blastomeres. Note the presence of Hoechst+ nuclei in the ICM that are negative for GATA6 (arrows) and Hoechst+ and GATA6+ nuclei in the edge of the ICM (arrowheads). Scale bars = 50 μm.

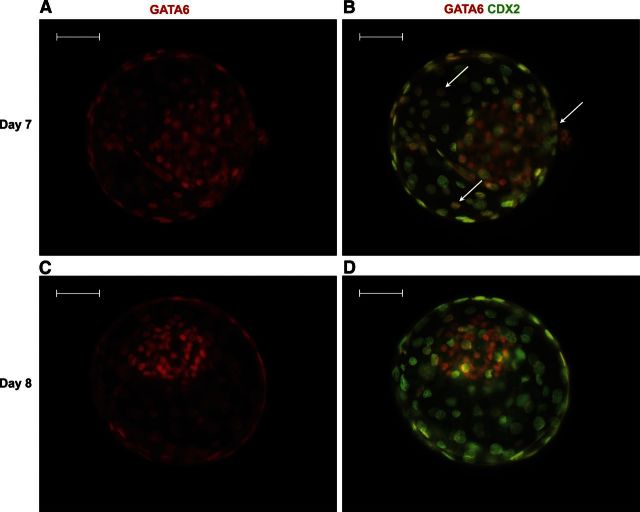

Figure 2.

Immunolocalization of GATA6 in blastocysts at d 7 and d 8 of development. A, B) Note that GATA6+ cells were widely distributed in both the ICM and TE at d 7. Arrows in panel B indicate cells clearly labeled for both GATA6 and CDX2. C, D) By d 8, labeling for GATA6 became more intense for ICM and less intense for TE and very few cells in the TE were labeled for GATA6. Scale bar = 50 μm.

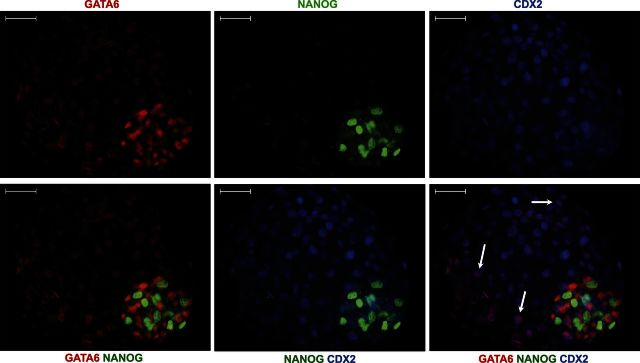

Figure 3.

Immunolocalization of NANOG, GATA6, and CDX2 in blastocysts at d 8 of development. NANOG+ cells were localized primarily in the center of the ICM, whereas GATA6+ cells were present primarily in the periphery of the ICM. Note the presence of faint GATA6 staining in the CDX2+ TE (arrows). Scale bars = 50 μm.

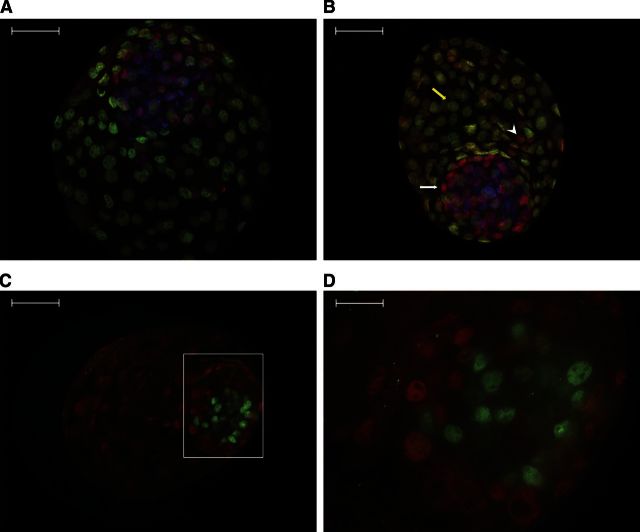

Figure 4.

Immunolocalization of GATA6, CDX2, and NANOG in d 8 blastocysts as visualized by confocal microscopy. A, B) Embryos labeled with GATA6 (red), CDX2 (green), and Hoechst (blue). In panel B, note that the TE has GATA6+ (arrowhead) as well as GATA6− cells (yellow arrow); also note the GATA6+ cell in the ICM, which represents a hypoblast cell (white arrow). C, D) Immunolocalization of GATA6 (red) and NANOG (green) in the ICM. D) Same embryo as in panel C but at higher magnification. Note that GATA6+ cells are in the periphery of the ICM, whereas NANOG+ cells are in the center of the ICM. Scale bar = 50 μm (A−C); scale bar = 16.7 μm (D).

DKK1 regulates cell lineage commitment in the blastocyst

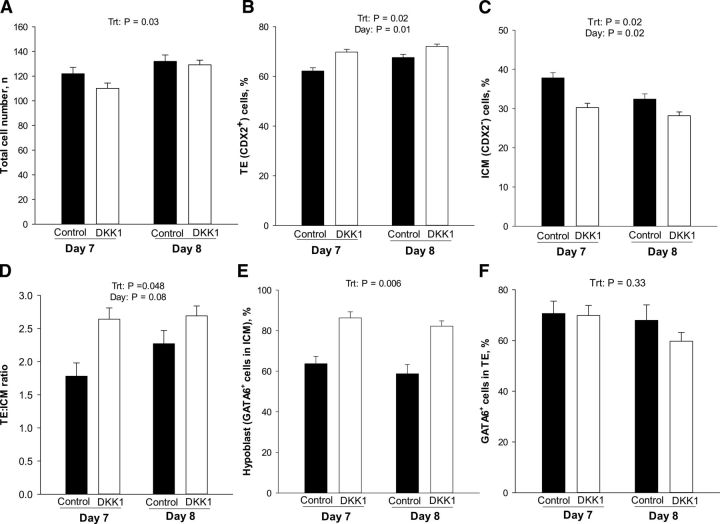

The effect of DKK1 on the total number of blastomeres, as well as the percentage of blastomeres that were TE, ICM, epiblast, and hypoblast cells is shown in Fig. 5. DKK1 reduced the total number of cells of blastocysts (P=0.03; Fig. 5A). Although the interaction was not significant, this difference was more pronounced at d 7 than at d 8. In addition, at both d 7 and 8, DKK1 increased (P=0.02) the percentage of cells labeled as TE (i.e., expressing CDX2; Fig. 5B), decreased (P=0.02) the percentage of cells classified as ICM (CDX2−; Fig. 5C), and increased the TE/ICM ratio (P=0.048; Fig. 5D). In addition, DKK1 increased (P=0.006) the percentage of cells in the ICM classified as hypoblast (GATA6+/CDX2−; Fig. 5E). There was no effect of DKK1 on the percentage of cells in the TE that were labeled with anti-GATA6 (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

DKK1 promotes lineage commitment. Results are least squares means ± sem for total cell number (A), percentage of blastomeres that were TE (CDX2+ cells; B) and ICM (CDX2− cells; C), TE/ICM ratio (D), percentage of blastomeres that were hypoblast (GATA6+ cells in ICM; E), and percentage that were GATA6+ in the TE (F) in blastocysts at d 7 and d 8. Treatment with DKK1 or vehicle started at d 5 of development. P values for individual tests appear on top of each graph when effects were significant. Trt, treatment.

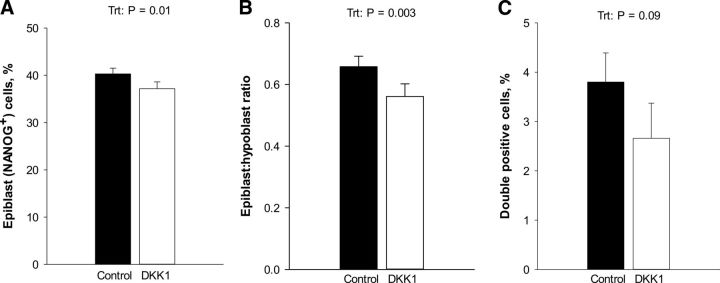

Expression of the pluripotency factor NANOG was examined at d 8 (the protein is weakly expressed at d 7; ref. 43). DKK1 decreased (P=0.01) the percentage of cells in the ICM (i.e., CDX2− cells) that were NANOG+ (i.e., committing to the epiblast lineage; Fig. 6A). Accordingly, the ratio of epiblast/hypoblast cells was decreased by DKK1 (P=0.003; Fig. 6B). The percentage of cells positive for both NANOG and GATA6 was low for both groups but tended (P=0.09) to be reduced by DKK1 (Fig. 6C), suggesting acceleration of the process of cell commitment to 1 of the 2 lineages.

Figure 6.

DKK1 promotes differentiation of the ICM in the d 8 blastocyst. Results are least squares means ± sem for the percentage of cells in the ICM that are epiblast cells (NANOG+; A), ratio of epiblast/hypoblast (NANOG+/GATA6+; B), and percentage of cells in the ICM that are double positive for GATA6 and NANOG (C). Treatment with DKK1 or vehicle began at d 5 of development. P values for individual tests appear on top of each graph when effects were significant. Trt, treatment.

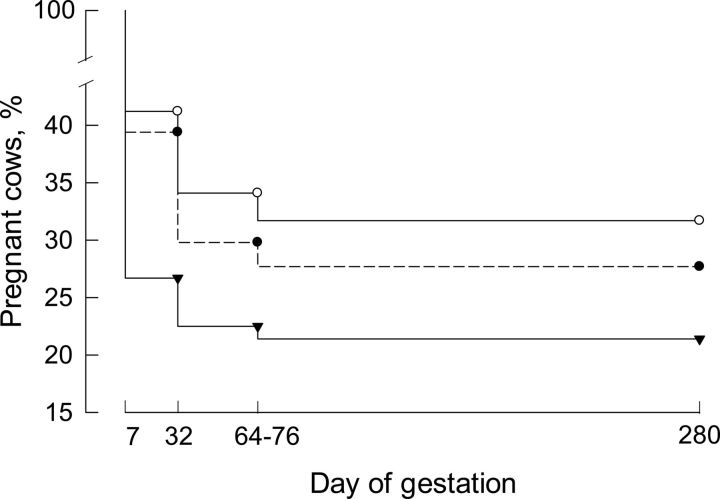

DKK1 and CSF2 improve embryo survival and pregnancy rate after ET

The pregnancy rate at d 32 of gestation was higher (P=0.046) for cows receiving an embryo that was treated with either DKK1 or CSF2 than for cows receiving a control embryo (Table 1). Significant differences were not detected, however, when pregnancy status was evaluated at d 64–76 of gestation or at parturition. The lack of significance was probably due to a reduction in the numbers of animals (some cows left the herd after the second pregnancy diagnosis) and the fact that pregnancy loss after the first diagnosis was numerically (but not significantly) greater for cows receiving a DKK1- or CSF2-treated embryo. Survival curves for pregnancy from d 7 to term were different between cows receiving a DKK1- or CSF2-treated embryo vs. those receiving a control embryo (P=0.032; Fig. 7). As a result, there was a numerically greater number of live births in the DKK1 and CSF2 groups than in the control group.

Table 1.

Consequences of treatment of embryos from d 5–7 of development on establishment and maintenance of pregnancy after transfer to recipients

| Treatment | Pregnancy rate, % (n/n) |

Calving, % (n/n) | Pregnancy loss, % (n/n) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d 32 | d 64–76 | d 32 to d 64–76 | d 64–76 to calving | d 32 to calving | ||

| Vehicle | 26.7 (19/71)a | 22.5 (16/71)a | 21.4 (15/70)a | 15.8 (3/19)a | 0 (0/16)a | 16.7 (3/18)a |

| DKK1 | 41.2 (35/85)b | 34.1 (29/85)a | 31.7 (26/82)a | 17.1 (6/35)a | 0 (0/26)a | 18.8 (6/32)a |

| CSF2 | 39.4 (37/94)b | 29.8 (28/94)a | 27.7 (26/94)a | 24.3 (9/37)a | 7.1 (2/28)a | 29.7 (11/37)a |

No difference between superscript letters indicates no significant difference.

Vehicle vs. CSF2 + DKK1: P = 0.046.

Figure 7.

Survival analysis for pregnancy outcomes after transfer of control embryos or embryos treated with DKK1 or CSF2 to recipients. The survival curve for control embryos was different (P=0.032) from those for DKK1- and CSF2-treated embryos. Controls are represented by triangles, DKK1 by open circles, and CSF2 by closed circles.

Characteristics of pregnancies at d 32–34

At d 32 of gestation, pregnant cows had higher (P=0.0001) concentrations of PAG (4.6±0.3 vs. 0.6±0.3 ng/ml for pregnant and nonpregnant cows, respectively) and progesterone (7.3±0.3 vs. 4.7±0.3 ng/ml for pregnant and nonpregnant cows, respectively) in plasma than nonpregnant cows. Among pregnant cows, however, neither concentrations of PAG (4.2±1.0, 5.3±0.6, and 4.1±0.6 ng/ml for vehicle, DKK1, and CSF2, respectively) nor those of progesterone (7.6±0.5, 7.7±0.4, and 7.1±0.4 ng/ml for vehicle, DKK1, and CSF2, respectively) were affected by treatment.

In a subgroup of pregnant cows reexamined at d 34 of gestation, DKK1-treated embryos tended (P=0.08) to be longer (1.51±0.06 cm) than CSF2-treated (1.36±0.06 cm) and vehicle-treated (1.38±0.08 cm) embryos.

Treatment of embryos with DKK1 and CSF2 affects expression of ISG15

Leukocytes from maternal blood at d 20 of embryo development were used to determine expression of ISG15, an interferon-induced gene regulated by the trophoblast signal interferon-τ (IFN-τ). Cows pregnant with a DKK1 or CSF2 embryo at d 32 had ISG15 expression at d 20 that was 2.7 ± 0.4- and 3.0 ± 0.6-fold higher (P=0.0001), respectively, than that of cows receiving a control embryo and diagnosed as nonpregnant at d 32 (1.3±0.3). In the cows pregnant to a control embryo, in contrast, pregnancy status did not significantly affect expression of ISG15 (1.7±0.3-fold compared with cows diagnosed as nonpregnant at d 32).

DISCUSSION

It is well established that the maternal environment is critical for ensuring normal preimplantation development (1, 3, 4, 6, 44, 45). Nonetheless, the specific regulatory molecules involved in this process and their actions on the embryo are not well understood. Here we demonstrate a novel role for one endometrially derived molecule, DKK1, as a modulator of signaling by embryo-derived WNTs. Data presented here lead to the conclusion that DKK1 limits the pluripotency-promoting actions of WNTs on the embryo and thereby facilitates differentiation of blastomeres into the first 2 derived lineages of the embryo (the TE and hypoblast). The extent to which maternal DKK1 modulates WNT signaling is likely to be an important determinant of whether an embryo can establish and maintain pregnancy. This is so because the present results indicate that DKK1 increased the competence of in vitro-produced embryos to establish pregnancy after transfer into females and also because maternal conditions associated with infertility are associated with reduced expression of DKK1 in the endometrium. In particular, DKK1 expression was higher in nonlactating cows than in lactating cows (28) and higher in bovine females that repeatedly became pregnant after multiple rounds of insemination vs. that in females that had 1 pregnancy after 4 insemination attempts (29). The role of DKK1 is probably of general relevance to mammalian reproduction because the gene is also expressed in the human (15, 25, 46, 47), mouse (27), horse (13), and sheep (12).

One well-established action of canonical WNTs (i.e., those that signal through stabilization of β-catenin) is in maintenance of the pluripotency of the cells of the ICM. Indeed, activation of canonical WNT signaling by inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is an important step for the maintenance of an undifferentiated state in embryonic stem cells (24). Activation of canonical WNT signaling can also reduce the numbers of TE cells in the cow (20) and pig blastocysts (22). The present findings that DKK1 increases the proportion of blastocyst cells that differentiate into TE and hypoblast while reducing the proportion that are ICM lends further credence to the idea that canonical WNTs maintain blastomeres in a pluripotent state.

The first 2 differentiation events in the blastocyst are driven by the transcription factors CDX2 (TE) and GATA6 (hypoblast), whereas NANOG is important for maintenance of the ICM in a pluripotent manner as epiblast precursors (48, 49). Developmental patterns of localization of GATA6 and NANOG seen here follow what was described earlier for the cow (43). GATA6 is localized in the nuclei of most cells in the ICM and TE at d 7 of development but then becomes increasingly restricted to the ICM by d 8. At this stage, GATA6+ cells in the ICM label brighter than those in the TE and labeling subsequently becomes largely restricted to the outer part of the ICM. NANOG+ cells at d 8 are limited in number and localized exclusively to ICM.

In the present study, abundant evidence indicated that DKK1 promotes segregation of the TE, epiblast, and hypoblast lineages, including an increase in the percentage of cells considered TE (CDX2+) and hypoblast (GATA6+ in ICM), a reduction in cells considered as epiblast (NANOG+ in ICM), and a reduction in the percentage of cells in the ICM at d 8 that were double positive for NANOG and GATA6. Although we do not have a clear understanding of the function of GATA6+ cells in the TE, we suggest that the loss of brightness concurrent with increased localization of GATA6+ cells in the ICM is a result of cessation of transcription of this factor in TE cells as the embryo develops. Note that the increase in the percentage of cells that were GATA6+ due to DKK1 treatment was solely due to a shift within the ICM population, because our labeling technique allowed us to accurately identify ICM and TE cells, and there was no effect of DKK1 on the percentage of GATA6+ cells presenting bright labeling within the TE.

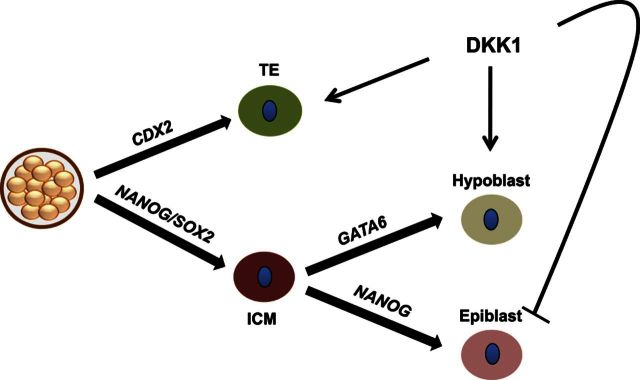

As shown in Fig. 8, we propose a model in which DKK1 acts to promote cell fate decisions in the early embryo, resulting in blastocysts with a higher proportion of embryonic cells committed to the TE fate, and a higher proportion of ICM cells differentiating into the hypoblast lineage. These cell segregation effects of DKK1 probably result from a shift between pluripotency and differentiation and are not reflective of an increased total cell number because DKK1 does not promote cell proliferation in the early embryo.

Figure 8.

Proposed model of the role of DKK1 in promoting cell fate decisions in the preimplantation embryo that lead to differentiation of the TE and hypoblast lineages. Results presented here indicate that DKK1 acts to increase the proportion of cells becoming TE and hypoblast while decreasing the percentage of cells in the ICM that are epiblast.

Although most of the work done to elucidate the actions of DKK1 points to its role in inhibiting WNT/β-catenin (canonical) signaling, DKK1 can also stimulate the planar cell polarity (noncanonical) pathway to promote cell movement during mouse gastrulation (50). Therefore, we cannot yet ascribe the actions of DKK1 to increase TE and hypoblast cell populations to regulation of canonical or noncanonical pathways.

One consequence of the actions of DKK1 on the preimplantation embryo was an increase in the competence of the blastocyst to establish pregnancy after transfer to a recipient female. Both DKK1 and CSF2, which was used as a positive control because it was previously shown to increase pregnancy rate after embryo transfer (9), resulted in embryos with a higher probability of establishing pregnancy after transfer. In addition, DKK1-treated embryos were longer at d 34 of gestation than CSF2-treated and control embryos. Perhaps, cell differentiation promoted by DKK1 during the morula-blastocyst periods resulted in a change in developmental programming to accelerate embryonic growth.

Because DKK1 increased the proportion of blastomeres that were TE at d 7 and 8, we evaluated the possibility that the increased pregnancy rate of DKK1-treated embryos resulted from an increase in trophoblast development and resultant secretion of IFN-τ, the antiluteolytic, trophoblast-derived protein that acts to inhibit prostaglandin F2α secretion from the uterus (51, 52). One action of IFN-τ is to increase the expression of the interferon-regulated gene ISG15 in peripheral leukocytes (39). Peripheral ISG15 expression for cows pregnant at d 32 of gestation after transfer of an embryo treated with DKK1 or CSF2 was increased at d 20 of gestation compared with that of cows that received a control embryo and were open at d 32, whereas pregnancy status did not significantly affect expression of ISG15 in cows receiving a control embryo. By d 32, trophoblast development appeared similar for embryos of all 3 types, at least based on circulating concentrations of PAGs, which are produced by trophoblast binucleated cells (53, 54).

The positive effect of CSF2 to reduce pregnancy losses after d 32 of gestation seen earlier (9) was not observed in the present study. Pregnancy loss was numerically higher in DKK1- and CSF2-treated embryos than in control embryos. One possibility to explain this finding is that exposure to DKK1 and CSF2 partially rescued embryos that would otherwise not have survived through maternal recognition of pregnancy and implantation. Unfortunately, the number of animals available to assess embryo survival after the initial pregnancy rate may have been insufficient to obtain a precise estimate of effects of treatment on pregnancy losses between d 32 and parturition. Overall, pregnancy maintenance to term was numerically higher for treated embryos and survival curves to calving differed between treated and control embryos. One practical outcome of the research is that these 2 maternally derived molecules may be important components of culture media for producing embryos in vitro for assisted reproductive techniques. Since the original report that CSF2 increased pregnancy rates of bovine embryos produced in vitro (9), this cytokine has subsequently been incorporated into embryo production systems in the human and shown to increase the live baby rate after embryo transfer (55).

In conclusion, we demonstrate here that DKK1, an inhibitor of the canonical WNT signaling pathway, promotes the cell differentiation events necessary for blastocyst formation and continued development. Furthermore, exposure of embryos to DKK1 during early development is sufficient to improve the embryo's ability to survive after transfer. We propose that endometrially derived DKK1 promotes cell fate decisions and trophoblast development in the preimplantation embryo in a way that changes the developmental program of the embryo and promotes its survival. It is hypothesized that these actions of DKK1 represent modulation of WNT signaling mediated by embryonic WNTs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Central Beef LLC (Center Hill, FL, USA) for providing bovine ovaries, Luciano Bonilla for assistance with embryo production and transfer, William Rembert for ovary collection, Eric Diepersloot of the University of Florida Dairy Research Unit and the owners and personnel at Alliance Dairies for support and assistance with the embryo transfer experiments, Douglas Smith and the University of Florida McKnight Brain Institute Cell and Tissue Analysis Core for technical assistance for acquisition of confocal images, and Glaucio Lopes and Accelerated Genetics for support of the trial.

This research was funded by U.S. Department of Agriculture Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI) grants 2009-65203-05732 and 2011-67015-30688.

A.C.D and P.J.H. designed the research; A.C.D., J.B., D.E.K., K.G.P., K.B.D., M.S.O., and C.J.M. performed the research; A.C.D. and P.J.H. analyzed the data; and A.C.D. and P.J.H. wrote the initial drafts of the article.

Footnotes

- BE1

- bovine embryo 1

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- CDX2

- caudal type homeobox 2

- CSF2

- colony-stimulating factor 2

- DKK1

- Dickkopf-1

- DPBS

- Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GATA6

- GATA binding protein 6

- ICM

- inner cell mass

- IFN-τ

- interferon-τ

- ISG15

- interferon stimulated gene 15 ubiquitin-like modifier

- NANOG

- Nanog homeobox

- PAG

- pregnancy-associated glycoprotein

- PVP

- polyvinylpyrrolidone

- SOF

- synthetic oviductal fluid

- TE

- trophectoderm

- WNT

- wingless-related mouse mammary tumor virus

REFERENCES

- 1. Farin P. W., Farin C. E. (1995) Transfer of bovine embryos produced in vivo or in vitro: survival and fetal development. Biol. Reprod. 52, 676–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pontes J. H., Nonato-Junior I., Sanches B. V., Ereno-Junior J. C., Uvo S., Barreiros T. R., Oliveira J. A., Hasler J. F., Seneda M. M. (2009) Comparison of embryo yield and pregnancy rate between in vivo and in vitro methods in the same Nelore (Bos indicus) donor cows. Theriogenology 71, 690–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bauer B. K., Isom S. C., Spate L. D., Whitworth K. M., Spollen W. G., Blake S. M., Springer G. K., Murphy C. N., Prather R. S. (2010) Transcriptional profiling by deep sequencing identifies differences in mRNA transcript abundance in in vivo-derived versus in vitro-cultured porcine blastocyst stage embryos. Biol. Reprod. 83, 791–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lazzari G., Colleoni S., Lagutina I., Crotti G., Turini P., Tessaro I., Brunetti D., Duchi R., Galli C. (2010) Short-term and long-term effects of embryo culture in the surrogate sheep oviduct versus in vitro culture for different domestic species. Theriogenology 73, 748–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gad A., Hoelker M., Besenfelder U., Havlicek V., Cinar U., Rings F., Held E., Dufort I., Sirard M. A., Schellander K., Tesfaye D. (2012) Molecular mechanisms and pathways involved in bovine embryonic genome activation and their regulation by alternative in vivo and in vitro culture conditions. Biol. Reprod. 87, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giritharan G., Delle Piane L., Donjacour A., Esteban F. J., Horcajadas J. A., Maltepe E., Rinaudo P. (2012) In vitro culture of mouse embryos reduces differential gene expression between inner cell mass and trophectoderm. Reprod. Sci. 19, 243–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheung L. P., Leung H. Y., Bongso A. (2003) Effect of supplementation of leukemia inhibitory factor and epidermal growth factor on murine embryonic development in vitro, implantation, and outcome of offspring. Fertil. Steril. 80, 727–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sagirkaya H., Misirlioglu M., Kaya A., First N. L., Parrish J. J., Memili E. (2007) Developmental potential of bovine oocytes cultured in different maturation and culture conditions. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 101, 225–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loureiro B., Bonilla L., Block J., Fear J. M., Bonilla A.Q., Hansen P. J. (2009) Colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF-2) improves development and posttransfer survival of bovine embryos produced in vitro. Endocrinology 150, 5046–5054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonilla A. Q., Ozawa M., Hansen P. J. (2011) Timing and dependence upon mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling for pro-developmental actions of insulin-like growth factor 1 on the preimplantation bovine embryo. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 21, 107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clementi C., Tripurani S. K., Large M. J., Edson M. A., Creighton C. J., Hawkins S. M., Kovanci E., Kaartinen V., Lydon J. P., Pangas S.A., DeMayo F. J., Matzuk M. M. (2013) Activin-like kinase 2 functions in peri-implantation uterine signaling in mice and humans. PLoS Genet. 9, 003863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hayashi K., Burghardt R. C., Bazer F. W., Spencer T. E. (2007) WNTs in the ovine uterus: potential regulation of periimplantation ovine conceptus development. Endocrinology 148, 3496–3506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Atli M. O., Guzeloglu A., Dinc D. A. (2011) Expression of wingless type (WNT) genes and their antagonists at mRNA levels in equine endometrium during the estrous cycle and early pregnancy. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 125, 94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Franco H. L., Dai D., Lee K. Y., Rubel C. A., Roop D., Boerboom D., Jeong J. W., Lydon J. P., Bagchi I. C., Bagchi M. K., DeMayo F. J. (2011) WNT4 is a key regulator of normal postnatal uterine development and progesterone signaling during embryo implantation and decidualization in the mouse. FASEB J. 25, 1176–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Macdonald L. J., Sales K. J., Grant V., Brown P., Jabbour H. N., Catalano R. D. (2011) Prokineticin 1 induces Dickkopf 1 expression and regulates cell proliferation and decidualization in the human endometrium. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 17, 626–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Satterfield M. C., Song G., Hayashi K., Bazer F. W., Spencer T. E. (2008) Progesterone regulation of the endometrial WNT system in the ovine uterus. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 20, 935–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tulac S., Overgaard M. T., Hamilton A. E., Jumbe N. L., Suchanek E., Giudice L. C. (2006) Dickkopf-1, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling, is regulated by progesterone in human endometrial stromal cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 1453–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fan X., Krieg S., Hwang J. Y., Dhal S., Kuo C. J., Lasley B. L., Brenner R. M., Nayak N. R. (2012) Dynamic regulation of Wnt7a expression in the primate endometrium: implications for postmenstrual regeneration and secretory transformation. Endocrinology 153, 1063–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van der Horst P. H., Wang Y., van der Zee M., Burger C. W., Blok L. J. (2012) Interaction between sex hormones and WNT/β-catenin signal transduction in endometrial physiology and disease. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 358, 176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Denicol A. C., Dobbs K. B., McLean K. M., Carambula S. F., Loureiro B., Hansen P. J. (2013) Canonical WNT signaling regulates development of bovine embryos to the blastocyst stage. Sci. Rep. 3, 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aparicio I. M., Garcia-Herreros M., Fair T., Lonergan P. (2010) Identification and regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 during bovine embryo development. Reproduction 140, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lim K. T., Gupta M. K., Lee S. H., Jung Y. H., Han D. W., Lee H. T. (2013) Possible involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in hatching and trophectoderm differentiation of pig blastocysts. Theriogenology 79, 284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xie H., Tranguch S., Jia X., Zhang H., Das S. K., Dey S. K., Kuo C. J., Wang H. (2008) Inactivation of nuclear Wnt-β-catenin signaling limits blastocyst competency for implantation. Development 135, 717–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato N., Meijer L., Skaltsounis L., Greengard P., Brivanlou A. H. (2004) Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat. Med. 10, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kelly K. F., Ng D. Y., Jayakumaran G., Wood G. A., Koide H., Doble B. W. (2011) β-Catenin enhances Oct-4 activity and reinforces pluripotency through a TCF-independent mechanism. Cell Stem Cell 8, 214–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tulac S., Nayak N. R., Kao L. C., Van Waes M., Huang J., Lobo S., Germeyer A., Lessey B. A., Taylor R. N., Suchanek E., Giudice L. C. (2003) Identification, characterization, and regulation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in human endometrium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 3860–3866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peng S., Li J., Miao C., Jia L., Hu Z., Zhao P., Li J., Zhang Y., Chen Q., Duan E. (2008) Dickkopf-1 secreted by decidual cells promotes trophoblast cell invasion during murine placentation. Reproduction 135, 367–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cerri R. L., Thompson I. M., Kim I. H., Ealy A. D., Hansen P. J., Staples C. R., Li J. L., Santos J. E., Thatcher W. W. (2012) Effects of lactation and pregnancy on gene expression of endometrium of Holstein cows at day 17 of the estrous cycle or pregnancy. J. Dairy Sci. 95, 5657–5675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Minten M. A., Bilby T. R., Bruno R. G., Allen C. C., Madsen C. A., Wang Z., Sawyer J. E., Tibary A., Neibergs H. L., Geary T. W., Bauersachs S., Spencer T. E. (2013) Effects of fertility on gene expression and function of the bovine endometrium. PLoS One 8, 69444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rizos D., Carter F., Besenfelder U., Havlicek V., Lonergan P. (2010) Contribution of the female reproductive tract to low fertility in postpartum lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 93, 1022–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berg D. K., Smith C. S., Pearton D. J., Wells D. N., Broadhurst R., Donnison M., Pfeffer P. L. (2011) Trophectoderm lineage determination in cattle. Dev. Cell 20, 244–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cai K. Q., Capo-Chichi C. D., Rula M. E., Yang D. H., Xu X. X. (2008) Dynamic GATA6 expression in primitive endoderm formation and maturation in early mouse embryogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 237, 2820–2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mitsui K., Tokuzawa Y., Itoh H., Segawa K., Murakami M., Takahashi K., Maruyama M., Maeda M., Yamanaka S. (2003) The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell 113, 631–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dobbs K. B., Khan F. A., Sakatani M., Moss J. I., Ozawa M., Ealy A. D., Hansen P. J. (2013) Regulation of pluripotency of inner cell mass and growth and differentiation of trophectoderm of the bovine embryo by colony stimulating factor 2. Biol. Reprod. 89, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sakatani M., Alvarez N. V., Takahashi M., Hansen P. J. (2012) Consequences of physiological heat shock beginning at the zygote stage on embryonic development and expression of stress response genes in cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 95, 3080–3091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fields S. D., Hansen P. J., Ealy A. D. (2011) Fibroblast growth factor requirements for in vitro development of bovine embryos. Theriogenology 75, 1466–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parrish J. J., Krogenaes A., Susko-Parrish J. L. (1995) Effect of bovine sperm separation by either swim-up or Percoll method on success of in vitro fertilization and early embryonic development. Theriogenology 44, 859–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Robertson I., Nelson R. E. (1998) in Manual of the International Embryo Transfer Society (Stringfellow D.A., Seidel S.E., eds) pp. 103–116, International Embryo Transfer Society, Champaign, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Green J. C., Okamura C. S., Poock S. E., Lucy M. C. (2010) Measurement of interferon-tau (IFN-τ) stimulated gene expression in blood leukocytes for pregnancy diagnosis within 18–20d after insemination in dairy cattle. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 121, 24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Han H., Austin K. J., Rempel L. L., Hansen T. R. (2010) Low blood ISG15 MRNA and progesterone levels are predictive of non-pregnant dairy cows. J. Endocrinol. 191, 505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ozawa M., Hansen P. J. (2011) A novel method for purification of inner cell mass and trophectoderm cells from blastocysts using magnetic activated cell sorting. Fertil. Steril. 95, 799–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Green J. A., Parks T. E., Avalle M. P., Telugu B. P., McLain A. L., Peterson A. J., McMillan W., Mathialagan N., Hook R. R., Xie S., Roberts R. M. (2005) The establishment of an ELISA for the detection of pregnancy-associated glycoproteins (PAGs) in the serum of pregnant cows and heifers. Theriogenology 63, 1481–1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kuijk E. W., van Tol L. T., Van de Velde H., Wubbolts R., Welling M., Geijsen N., Roelen B. A. (2012) The roles of FGF and MAP kinase signaling in the segregation of the epiblast and hypoblast cell lineages in bovine and human embryos. Development 139, 871–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gad A., Besenfelder U., Rings F., Ghanem N., Salilew-Wondim D., Hossain M. M., Tesfaye D., Lonergan P., Becker A., Cinar U., Schellander K., Havlicek V., Hölker M. (2011) Effect of reproductive tract environment following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation treatment on embryo development and global transcriptome profile of blastocysts: implications for animal breeding and human assisted reproduction. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1693–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bridges G. A., Day M. L., Geary T. W., Cruppe L. H. (2013) Triennial Reproduction Symposium: deficiencies in the uterine environment and failure to support embryonic development. J. Anim. Sci. 91, 3002–3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kao L. C., Tulac S., Lobo S., Imani B., Yang J. P., Germeyer A., Osteen K., Taylor R. N., Lessey B. A., Giudice L. C. (2002) Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology 143, 2119–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang R. J., Zou L. B., Zhang D., Tan Y. J., Wang T. T., Liu A. X., Qu F., Meng Y., Ding G. L., Lu Y. C., Lv P. P., Sheng J. Z., Huang H. F. (2012) Functional expression of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in human endometrium: a novel mechanism involved in endometrial receptivity and embryo implantation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morris S. A., Zernicka-Goetz M. (2012) Formation of distinct cell types in the mouse blastocyst. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 55, 203–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xenopoulos P., Kang M., Hadjantonakis A. K. (2012) Cell lineage allocation within the inner cell mass of the mouse blastocyst. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 55, 185–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Caneparo L., Huang Y. L., Staudt N., Tada M., Ahrendt R., Kazanskaya O., Niehrs C., Houart C. (2007) Dickkopf-1 regulates gastrulation movements by coordinated modulation of Wnt/β catenin and Wnt/PCP activities, through interaction with the Dally-like homolog Knypek. Genes Dev. 21, 465–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Spencer T. E., Johnson G. A., Bazer F. W., Burghardt R. C. (2007) Fetal-maternal interactions during the establishment of pregnancy in ruminants. Soc. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 64, 379–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bazer F. W. (2013) Pregnancy recognition signaling mechanisms in ruminants and pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 4, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Green J. A., Xie S., Roberts R. M. (1998) Pepsin-related molecules secreted by trophoblast. Rev. Reprod. 3, 62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sousa N. M., Ayad A., Beckers J. F., Gajewski Z. (2006) Pregnancy-associated glycoproteins (PAG) as pregnancy markers in the ruminants. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 57, 153–171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ziebe S., Loft A., Povlsen B. B., Erb K., Agerholm I., Aasted M., Gabrielsen A., Hnida C., Zobel D. P., Munding B., Bendz S. H., Robertson S. A. (2013) A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in embryo culture medium for in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 99, 1600–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]