Abstract

Kidney epithelial sodium channels (ENaCs) are known to be inactivated by high sodium concentrations (feedback inhibition). Recently, the endothelial sodium channel (EnNaC) was identified to control the nanomechanical properties of the endothelium. EnNaC-dependent endothelial stiffening reduces the release of nitric oxide, the hallmark of endothelial dysfunction. To study the regulatory impact of sodium on EnNaC, endothelial cells (EA.hy926 and ex vivo mouse endothelium) were incubated in aldosterone-free solutions containing either low (130 mM) or high (150 mM) sodium concentrations. By applying atomic force microscopy-based nanoindentation, an unexpected positive correlation between increasing sodium concentrations and cortical endothelial stiffness was observed, which can be attributed to functional EnNaC. In particular, an acute rise in sodium concentration (+20 mM) was sufficient to increase EnNaC membrane abundance by 90% and stiffening of the endothelial cortex by 18%. Despite the absence of exogenous aldosterone, these effects were prevented by the aldosterone synthase inhibitor FAD286 (100 nM) or the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR)-antagonist spironolactone (100 nM), indicating endogenous aldosterone synthesis and MR-dependent signaling. Interestingly, in the presence of high-sodium concentrations, FAD286 increased the transcription of the MR by 69%. Taken together, a novel feedforward activation of EnNaC by sodium is proposed that contrasts ENaC feedback inhibition in kidney.—Korte, S., Sträter, A. S., Drüppel, V., Oberleithner, H., Jeggle, P., Grossmann, C., Fobker, M., Nofer, J.-R., Brand, E., Kusche-Vihrog, K. Feedforward activation of endothelial ENaC by high sodium.

Keywords: EnNaC, atomic force microscopy, endothelium, aldosterone, mineralocorticoid receptor, FAD286

High salt intake, common in industrial countries, is to some extent responsible for arterial hypertension and has harmful effects on the cardiovascular system independent of the rise in blood pressure (1–3). There is evidence that synergistic effects of salt and aldosterone enhance the development of cardiovascular complications (3–7). Aldosterone excess stiffens human endothelial cells, which, in turn, reduces the release of nitric oxide (NO) (8). This inverse correlation between cellular stiffness and NO release may be physiologically relevant since modifications of endothelial cell deformability alter the function of the vasculature (9).

A reduced release of NO due to endothelial stiffening causes impaired vasodilation of blood vessels, which promotes the development of endothelial dysfunction (9,10). Recently, this transition from endothelial function (normal levels of NO) to endothelial dysfunction (reduced levels of NO) was described as the stiff endothelial cell syndrome (SECS) (11). Up to now, a moderate rise of sodium concentration in the presence of aldosterone was shown to stiffen cultured endothelial cells within minutes and reducing NO release (12). Although it is obvious that mineralocorticoid and salt excess can cause arterial hypertension, it is presently not known how changes of sodium concentration induce these cellular responses. A possible mediator might be the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), also expressed in vascular endothelium (13–15) and recently termed endothelial sodium channel (EnNaC) (16, 17).

In epithelial tissues ENaC is described as a heteromultimer consisting of three homologous subunits (α, β, and γ) (for review see refs. 18, 19). From the pathophysiological point of view, ENaC has been shown to play a key role in Liddle's syndrome where mutations in the β- or γ-subunit lead to a gain-of-function of the channel (20). The expression and membrane insertion of ENaC are classically regulated by aldosterone via the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) (21, 22). High sodium concentrations normally reduce aldosterone synthesis in the adrenal cortex resulting in a decrease of renal Na+ reabsorption (23). In contrast, Kakizoe et al. (24) reported that the expression of EnNaC in the endothelium is increased in rats on a high-sodium diet, despite low plasma aldosterone. In this context, we found that the combination of aldosterone and high sodium concentrations (150 mM) stimulates the membrane insertion of functional EnNaC in human endothelial cells (25). Further, it was shown in vitro and ex vivo that the expression of EnNaC itself determines the mechanical properties of endothelial cells, thereby influencing NO release (9, 26). Such a link between EnNaC expression and mechanical properties of the endothelium support previous findings by Pérez et al. (13), namely that endothelial ENaC determines vasoconstriction by negatively modulating NO production in mesenteric arteries. From these findings, it can be inferred that the abundance of EnNaC in the endothelial membrane appears to be crucial for the function/dysfunction of the cell e.g., the mechanical stiffness, a mechanical property of the cell, which is crucial for its physiological function (for review, see refs. 17, 27).

Thus, the following sequence of events is likely: high sodium triggers the expression and membrane insertion of EnNaC, which stiffens the cell cortex resulting in a reduced secretion of NO. This, in turn, leads to SECS and, thus, impaired vascular function. Besides EnNaC, the MR has been identified in endothelial cells (28, 29). Moreover, the synthesis of aldosterone at sites different from the adrenal cortex has been debated for years. It has been recently demonstrated in brain (30, 31), heart (32), and vasculature (33, 34). An extra-adrenal source seems to be involved in the development of cardiac failure (35). Furthermore, the aldosterone synthase gene CYP11B2 has been identified in a number of different extra-adrenal tissues, e.g., blood vessels, heart, and brain (30, 32, 36).

The primary aim of the present work was to clarify the role of sodium as such as a regulator of EnNaC and as a key membrane protein in the development of endothelial dysfunction, independent of systemic aldosterone. Thus, the emerging hypothesis was tested whether high sodium per se triggers the membrane insertion of EnNaC via mineralocorticoid receptor signaling pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Endothelial cell culture

Immobilized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (EAhy.926; kindly donated by C.-J. S. Edgell, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA) were grown in culture, as described previously (12, 37). Briefly, endothelial cells were cultured in T25 culture flasks using DMEM medium (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with NaHCO3, penicillin G, streptomycin (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany), and FCS (PAA Clone, Coelbe, Germany). Chemicals were added to the medium as appropriate. Endothelial cells and ex vivo aorta preparations were incubated in 1) low sodium (130 mM), 2) high sodium (150 mM), 3) high sodium (150 mM) + FAD286 (100 nM; a kind gift from Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), and 4) high sodium (150 mM) + spironolactone (100 nM). Differences in osmolarity between 130 mM and 150 mM NaCl solutions were compensated by appropriate amounts of mannitol. Amiloride (10 μM) and benzamil (1 μM) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), both being selective blockers of ENaC, were acutely applied to the cells. Twenty-four hours prior to the experiments, cells were transferred into FCS-free medium to avoid contamination with exogenous aldosterone. To prevent any evaporation of water for maintaining constant sodium concentrations in the respective media, culture dishes were placed in a water-filled extra chamber inside a standard incubator.

Preparation of ex vivo mouse aortae

As described previously (38), the first ∼1.5 cm of aortae, from heart to diaphragm, were dissected from the mice and freed from surrounding tissue. A small patch (∼1 mm2) of the whole aorta was prepared and attached on Cell-Tak coated glass (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany), with the endothelial surface facing upward. Prior to the experiments, the preparations were kept in minimal essential medium (MEM) (Invitrogen) with the addition of 1% MEM vitamins, penicillin G (10,000 U/ml), streptomycin (10,000 μg/ml) (Biochrome AG), 1% NEAA and 20% FBS (PAA Clone) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The aortic preparations were then incubated under different sodium conditions for 72 h, as described above.

Determination of endogenous aldosterone in human endothelial cells

For the detection of endogenously produced aldosterone EAhy.926 cells were transferred into FCS-free medium for 24 h. Then, cells were incubated in low sodium (130 mM) or high sodium (150 mM) for 30 min. Cells and supernatant were collected separately, homogenized with a sonifier, and extracted twice with 2 ml dichloromethane. Aldosterone in the dichloromethane extract was then adsorbed onto a silica gel column (Sigma-Aldrich), prewashed with 3 ml of dichloromethane, and then eluted with 3 ml of dichloromethane containing 7% methanol. The organic extract was evaporated and reconstituted in 250 μl of ELISA buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% thimerosal, and 0.05% Tween 20) and used for the aldosterone assay (IBL, Hamburg, Germany). Original results of the ELISA were expressed as picograms per milliliter. The experiment was independently repeated 4 times.

Detection of CYP11B2 by RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from EAhy.926 following the standard protocol of RNeasy Minikit plus (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Contamination with genomic DNA was effectively removed with a gDNA eliminator spin column and DNase digestion, and tested with a RT minus control (not shown). About 1 μg of high-quality total RNA (assessed by spectrophotometry) was used to generate first-strand cDNA by using the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) and oligo (dT) primer. RT-PCR was performed in a thermal cycler (Mastercycler Gradient; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and PCR products were photographed on a UV transilluminator. For the detection of a specific fragment of human CYP11B2 (348 bp), the following primers were used: 5′-TTGCCAGGCTTGTCAAATAG-3′ and 5′-TTTCAGAGAGCTCAGGGCAT-3′. For identification, this fragment was cloned into TOPO TA vector (Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA, USA) and sequenced by a commercial sequencing service (Genterprise, Mainz, Germany).

Quantification of MR- and ENaC-mRNA by qRT-PCR

For the mRNA analysis, EAhy.926 cells were transferred into FCS-free medium either in low (130 mM) or high sodium (150 mM) 24 h prior to the experiments. About 200 ng of total EAhy.926 RNA was used to generate first-strand cDNA applying the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) and oligo (dT) primer. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was either performed using a Stratagene Mx 3005P system with the Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen; MR) or using the Absolute QPCR SYBR Green ROX Mix (ThermoScientific, Schwerte, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions, respectively. Each experimental group was analyzed 5 times in duplicate employing the following primers: αENaC: 5′-CTCTGTCACGATGGTCACCCTCC-3′ (sense), 5′-CAGCAGGTCAAAGACGAGCTCAG-3′ (antisense); Gap-DH: 5′-CTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGCAC-3′ (sense), 5′-CACCACCATGGAGAAGGCTGGGG-3′ (antisense); MR: 5′-ATCACGATCGGCTAGAGACC-3′ (sense), 5′-CCCATAATGGCATCCTGAAG-3′ (antisense); 18S: 5′-GCATATGCTTGTCTCAAAGA-3′ (sense), 5′-CCAAAGGAACCATAACTGAT-3′ (antisense). β-actin: 5′-GCACAGAGCCTCGCCTT-3′ (sense); 5′-CCTTGCACATGCCGGAG-3′ (antisense). RT minus reactions were performed as a control for each group (not shown). The relative expression of mRNA was calculated according to the 2ΔΔC method, using 18S (MR) and Gap-DH (ENaC) for normalization. Values represent the relative expression in relation to untreated cells (130 mM Na+).

Detection of cellular EnNaC and CYP11B2 by Western blot analysis

Endothelial cells (EAhy.926) were incubated for either 72 h or 30 min (therefrom 24 h in FCS-free) medium in three experimental setups: low sodium (130 mM), high sodium (150 mM), and high sodium (150 mM) plus FAD286. Then, proteins were isolated by using the ProteoExtract transmembrane protein extraction kit (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Protease inhibitor cocktail was included and added to this detergent mixture. For Western blot analysis, 30–40 μg protein was loaded onto SDS-PAGE (7.5% acrylamide) and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked 4 h by 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween (TBST) (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4; 140 mM NaCl; 0.3% Tween 20). The epithelial sodium channel α-subunit was detected with a rabbit anti-α-ENaC antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) at a concentration of 1:2000 diluted in 5% nonfat dry milk/TBST, while a β-actin antibody was used as a loading control. The goat polyclonal anti-CYP11B2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) was applied to the cells 1:250. Horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit and rabbit anti-goat antibodies, respectively, were used for ECL detection (Sigma-Aldrich). Blots were semiquantitatively analyzed by densitometry using ImageJ analysis software 1.36 (39).

Detection of plasma membrane EnNaC by immunofluorescence microscopy

As described previously, human endothelial cells (EAhy.926) were stained with an anti-α-ENaC antibody, which binds to the extracellular loop of the protein (a kind gift from Dr. M. S. Awayda, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Buffalo University School of Medicine, Buffalo, NY, USA) (25, 40). Briefly, after fixation, cells were gently washed 5 times in PBS (in mM): 140 NaCl, 2 KCl, 4 Na2HPO4, and 1 KH2PO4, pH 7.4, at room temperature, and incubated afterward for 30 min in 100 mM glycine/PBS solution. The cells were washed again and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum (NGS) at room temperature for 1 h. The anti-α-ENaC antibody was used in a 1:1000 dilution. For quantum-dot (QD) labeling, cells were incubated with QD655 goat F(ab′)2 anti-rabbit IgG conjugates (1:100) (Quantum Dot, Hayward, CA, USA). Data acquisition and analysis were performed with the Metavue software (Visitron Systems, Puchheim, Germany).

Endothelial cell stiffness measurements in vitro and ex vivo

The stiffness of living EAhy.926 endothelial cells was measured with soft cantilevers (MLCT-contact microlevers, spring constant: 0.01 N/m; Bruker, Mannheim, Germany) equipped with 10 Ø-μm colloidal tips (Novascan, Ames, IA) as described previously (12). As the cantilever indents the cell, it bends. This bending can be measured by a laser beam reflected from the gold-coated cantilever. Taking the cantilever's spring constant and the cantilever's sensitivity into account, the data can then be transformed into a force vs. distance curve of single cells. The slope of such curves is directly related to the force (expressed in newtons), defined as stiffness (newtons per meter) necessary to indent the cell for a given length (indentation depth: ∼200 nm). Experiments were performed on living cells at 37°C by using a Multimode atomic force microscope (AFM;Bruker) and a feedback-controlled heating device. During the measurements, the cells were bathed in HEPES-buffered solution with appropriate Na+ concentrations (130 or 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM glucose, pH 7.4). Differences in osmolarity between 130 mM and 150 mM Na+ solutions were compensated by appropriate amounts of mannitol. Stiffness measurements of ex vivo endothelial cells from mouse aortae were performed as described previously (26, 38).

Measurements of intracellular sodium concentration

Intracellular sodium measurements were performed on confluent EAhy.926 cell layers seeded on glass-bottom dishes (Willco Wells, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and mounted onto an inverted fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200; Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a charge-coupled device camera (CoolSNAP; Visitron Systems). [Na+]i was measured using the Na+-sensitive fluorescent dye sodium binding benzofuran isophthalate (SBFI; Molecular Probes, Darmstadt, Germany), as described elsewhere (25). Before loading the cells with the dye, SBFI was mixed with an equal volume of 25% (wt/vol) Pluronic-127 in 1% DMSO. Endothelial monolayers were incubated with a final SBFI-concentration of 10 μM in HEPES-buffered medium for at least 3 h at 4°C. The loaded cells were then washed and incubated in dye-free buffer for 30 min. After incubation, the nondeesterized dye was washed off, and measurements were started at room temperature. Cells were perfused for at least 5 min with appropriate solutions (low sodium, high sodium, or high sodium + FAD 286) containing 10 μM amiloride, which was washed off during the experiments. For fluorescence recordings, excitation light (VisiChrome Polychromatic Illuminations System; Visitron Systems) was passed alternately through 340- and 380-nm band-pass filters for 300 and 100 ms, respectively. The [Na+]i-dependent SBFI fluorescence was measured at 500 nm. The ratio was obtained by dividing the emitted light signals at 340 nm and 380 nm after subtraction of the background emission at these wavelengths. For calibration, the SBFI-loaded endothelial cells were perfused with two calibration solutions (containing HEPES-buffered solution with Na+ concentrations of 0 and 150 mM, respectively, and in the presence of the ionophore gramicidin, 1 μM), whereby sodium was replaced by appropriate amounts of mannitol if applicable. The emitted light ratio could be converted into intracellular Na+ concentration, as described previously (25, 41). The calibration procedure yields a Kd value of SBFI for Na+ of 13.3 ± 0.78 mM (mean, n=47).

Statistics

Significance of difference in the statistics was determined using 1-way ANOVA and 2-sample Student's t test in case of a normally distributed population or using Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA and Mann-Whitney U-test for populations that did not follow a normal distribution (*P<0.05). All depicted data were calculated as medians ± sd or as means ± se, depending on normal distribution.

RESULTS

Aldosterone is endogenously produced in endothelial cells

To detect endogenously produced aldosterone, endothelial cells were incubated for 30 min in aldosterone-free medium. Aldosterone was detected in the cell lysates of four independent series of experiments. In addition, aldosterone was detected in the supernatant medium of each experimental approach, which indicates that the cells secrete endogenously produced aldosterone. About 5 × 106 human endothelial cells produce 132 pg/m (≈0.366 nM) aldosterone, when incubated in low sodium concentration (130 mM) and 149 pg/ml (≈0.414 nM, high sodium concentration, 150 mM). The fact that endothelial cells are able to produce aldosterone on their own is in agreement with findings from other groups (33, 34).

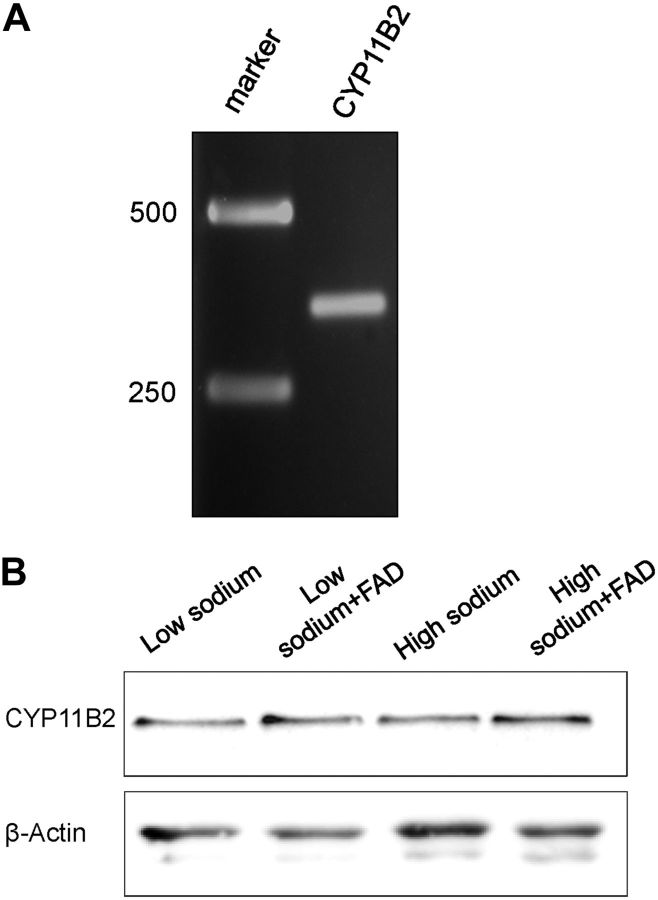

CYP11B2 is expressed in human endothelial cells

It was previously shown that endothelial cells express EnNaC (14, 42) and MR (28, 29). Here, experiments were performed to test whether human endothelial cells (EA.hy926) also express the aldosterone synthase CYP11B2. To this end, a reverse transcription reaction (RT-PCR) was applied to demonstrate the expression of the CYP11B2 mRNA in EA.hy926 endothelial cells (Fig. 1A). To confirm the PCR results, the fragment was cloned and sequenced by comparing the fragment with GenBank entries using BLAST, we found a 100% analogy with the expected cDNA sequence. Additionally, the expression of CYP11B2 in EA.hy926 cells was demonstrated via Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B). The findings confirm previous reports in that vascular endothelium can synthesize aldosterone de novo by expressing CYP11B2 and other genes essential for the aldosterone signaling pathway (33, 34).

Figure 1.

Detection of CYP11B2. A) Detection of the aldosterone synthase CYP11B2 with specific primers (∼348 bp fragment). Left lane: marker = 1 kb DNA marker. B) Western blot analysis shows the expression of CYP11B2 in EA.hy926 endothelial cells (n=3). Incubation in different sodium concentrations (low=130 mM, high=150 mM), and inhibition of the aldosterone synthase CYP11B2 with FAD286 (FAD) has obviously no effect on the expression.

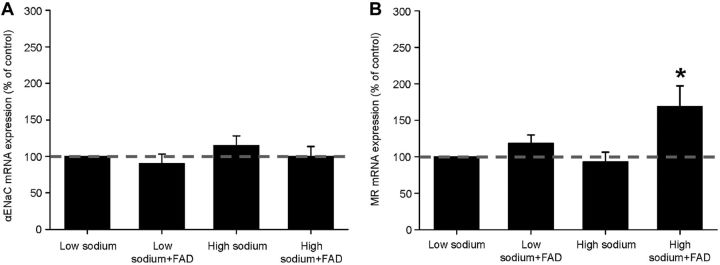

High sodium and inhibition of the aldosterone synthase stimulate MR mRNA expression

High sodium concentrations are known to decrease suprarenal aldosterone production and thus, in kidney, decrease the expression of ENaC. To test whether high sodium concentrations influence the transcription of the αEnNaC or the MR in the endothelium the mRNA levels for both transcripts were quantified via quantitative RT-PCR. However, chronic incubation of the cells in aldosterone-free medium with high sodium concentrations alone did not show any effect on the mRNA expression of endothelial ENaC and MR (Fig. 2). Interestingly, by simulating a physiological situation with high sodium concentration/low aldosterone (mimicked by administration of the aldosterone synthase blocker FAD286), the mRNA expression of MR was significantly increased by 69 ± 0.28% (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Quantification of EnNaC- and MR-mRNA levels. A) The mRNA expression of the EnNaC is not changed with chronic incubation in low and high sodium, with or without FAD286 (n=3). B) Treatment of the cells with high sodium concentrations and the CYP11B2 blocker FAD286 increases the mRNA expression of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) by 69 ± 0.28% compared to the control (low sodium). *P=0.026 vs other groups (n=5).

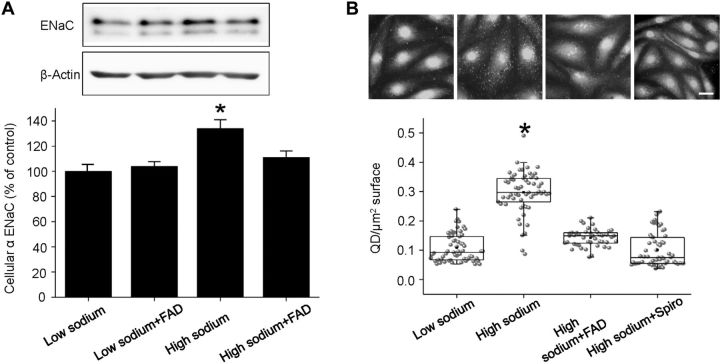

High sodium increases EnNaC protein abundance

The presence of α-EnNaC in human endothelial cells was confirmed by Western blot analyses with specific anti-αENaC antibodies. Incubation of the cells for 72 h in aldosterone-free high-sodium medium significantly enhanced EnNaC abundance by 34% compared to low-sodium conditions. When cells were incubated in 150 mM sodium together with the aldosterone synthase blocker FAD286, the increase in cellular EnNaC was prevented (Fig. 3A). In contrast, exposure of the cells for 30 min to high sodium has obviously no effect at EnNaC protein level (Fig. 4A).

Figure 3.

Chronic high sodium increases the cellular and membrane abundance of EnNaC. Endothelial cells were incubated for 72 h in different experimental conditions: low sodium (130 mM), low sodium + FAD286, high sodium (150 mM), high sodium (150 mM) + FAD286 and high sodium (150 mM) + spironolactone (Spiro). A) Detection of αEnNaC in EA.hy926 endothelial cells (representative Western blot). Chronic exposure (72 h) of endothelial cells to 150 mM sodium increases the whole cell EnNaC abundance significantly. Low sodium + FAD286 shows no effect while addition of FAD286 to high sodium prevents the increase of cellular ENaC. The ∼65-kDa band corresponds to full-length αENaC, while the ∼58-kDa band corresponds to a cleaved form of αENaC. B) Representative images of immunofluorescence stainings of endothelial cells with a specific anti α-ENaC antibody and a QD-labeled secondary antibody. Scale bar = 10 μm. No exogenous aldosterone was added. Chronic high-sodium incubation significantly increases the surface abundance of ENaC. Inhibition of CYP11B2 with FAD286 and MR with spironolactone prevents the effect. *P < 0.05 vs. other groups; 2-sample Student's t test (n=60).

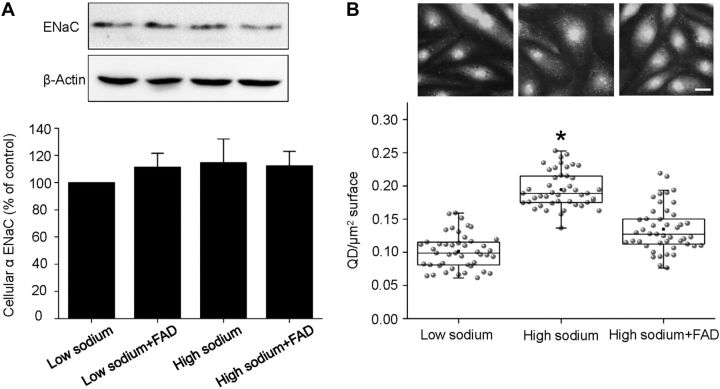

Figure 4.

High sodium acutely increases plasma membrane abundance but not the expression of EnNaC. Endothelial cells were incubated for 30 min in different experimental conditions in FCS-free medium: low sodium (130 mM), low sodium+FAD286 high sodium (150 mM), and high sodium (150 mM) plus FAD286. A) Detection of αEnNaC in EA.hy926 endothelial cells (representative Western blot). Western blot analysis of α-EnNaC reveals that acute (30 min) exposure to high sodium has no effect on the expression of ENaC (n=6). B) Representative images of immunofluorescence stainings of endothelial cells with a specific anti α-EnNaC antibody and a QD-labeled secondary antibody. Scale bar = 10 μm. High sodium acutely increases plasma membrane EnNaC. Block of the endogenous aldosterone synthase with FAD286 prevents this effect. *P ≤ 0.05 vs other groups; 2-sample Student's t test (n=45).

High sodium increases EnNaC membrane abundance

Immunostaining for αEnNaC on the endothelial cell surface was performed to test whether high-sodium/endogenous aldosterone increase the membrane abundance of EnNaC in endothelial cells. Therefore, cells were kept for 72 h in an aldosterone-free medium with either low or high sodium. The sodium channel was stained with specific anti-α-ENaC antibodies and QD-labeled secondary antibodies to quantify EnNaC in the plasma membrane (25, 40). As shown in Fig. 3B, 72-h incubation in high-sodium concentrations significantly increases the number of detectable QD at the surface of endothelial cells from 0.11 ± 0.006 QD/μm2 cell surface (low sodium condition) to 0.29 ± 0.009 QD/μm2 cell surface. Coincubation in high sodium and FAD286 or spironolactone prevents ENaC membrane accumulation. The specificity of the primary antibody was tested by using siαENaC (knockdown) endothelial cells and ex vivo endothelial cells derived from conditional αENaC-knockout mice as negative controls. In the siαENaC, the EnNaC membrane abundance was reduced by 22% (24), whereas in the αENaC-knockout endothelial cells, no specific signal could be detected (data not shown).

High sodium acutely increases the membrane abundance of EnNaC

To study whether the action of high sodium/endogenous aldosterone can also be attributed to an acute/fast mechanism, cells were stimulated for only 30 min with high sodium (aldosterone-free condition). The abundance of EnNaC molecules in the cell membrane was determined via immunostaining for αEnNaC, as described above. Under these conditions, the number of detectable QD on the surface of endothelial cells was increased within 30 min from 0.10 ± 0.003 QD/μm2 cell surface to 0.19 ± 0.004 QD/μm2 cell surface (Fig. 4B). FAD286 prevented this acute response.

High sodium stiffens endothelial cells

An AFM was used as a nanosensor to evaluate the mechanical stiffness of endothelial cells during stimulation with low and high sodium, respectively. Incubation in high-sodium medium for 72 h led to an increase in the mechanical stiffness by 18% (n=50), compared to cells kept in low-sodium medium (n=37). This increase in stiffness could be prevented by application of the aldosterone synthase blocker FAD286 (−21% n=41), the ENaC inhibitor benzamil (−25%, n=42) or the aldosterone receptor antagonist spironolactone (−26% n=24) (Fig. 5). It is known that aldosterone/high-sodium concentrations lead to an amiloride-sensitive increase in cellular stiffness (12). The present study is the first to show that high sodium per se (in the absence of exogenous aldosterone) leads to cellular stiffening. As FAD286 prevents this increase in stiffness, it is most likely a result of endogenous aldosterone synthesis.

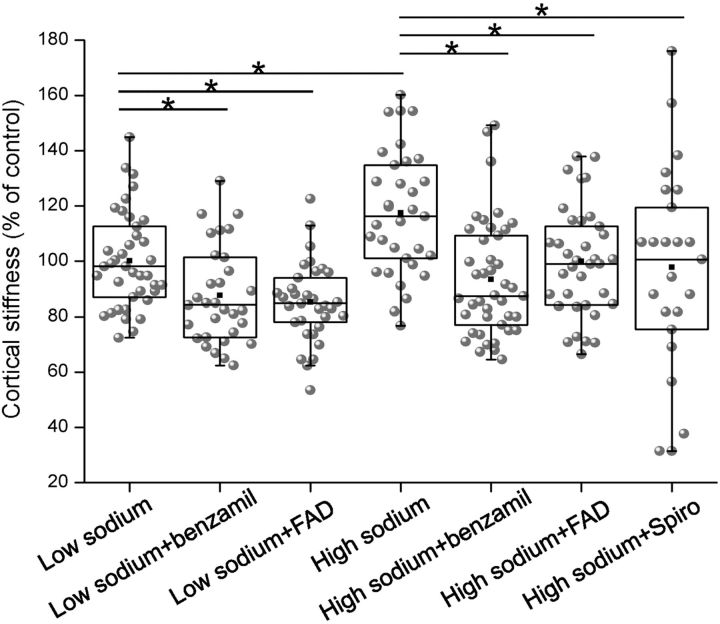

Figure 5.

High sodium increases the mechanical stiffness of the cell cortex. The mechanical stiffness of endothelial cells was determined using atomic force microscopy. 72-h exposure to high sodium concentrations (150 mM) in FCS-free medium stiffens the cells, which is prevented by benzamil, FAD286, and spironolactone. (Number of force measurements: low=130 mM: n=39; 130 mM+benzamil: n=31, 130 mM+FAD: n=33, high=150 mM: n=33; 150 mM+benzamil: n=42, 150 mM+FAD: n=36, 150 mM+Spiro: n=24.) *P < 0.05 vs. other groups; Mann-Whitney U test.

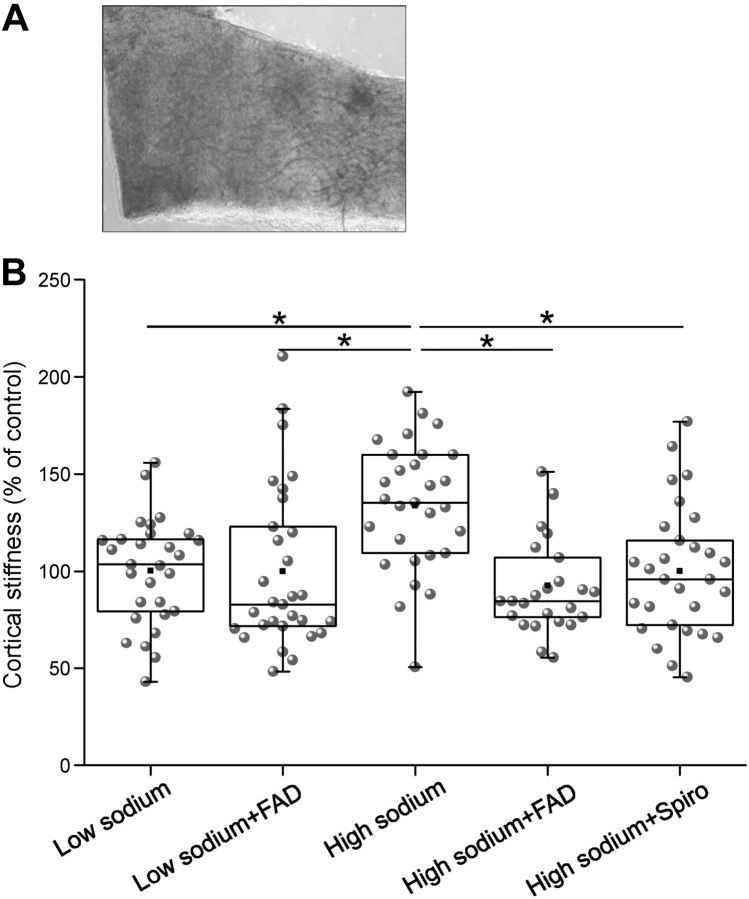

To study the effects of high sodium in a more physiological context, stiffness measurements were also performed in ex vivo endothelial cells. To this end, preparations of mouse aortae were identically incubated as cultured endothelial cells, and AFM measurements were performed (Fig. 6). It could be shown that high sodium increases the mechanical stiffness of the cells by ∼41% (2.4±0.76 pN/nm; n=30) compared to low sodium (1.7±0.46 pN/nm; n=29). FAD286 prevents the stiffness increase (1.77±0.83 pN/nm; n=27) similar as a MR blockade with spironolactone (1.7±0.56 pN/nm; n=29). These results confirm the in vitro data.

Figure 6.

High sodium increases the mechanical stiffness of ex vivo mouse aortae. A) A small patch of the mouse arterial wall (∼1 mm2) is attached to the glass surface. Endothelial surface faces upward. B) Mean stiffness values of ex vivo mouse endothelial cells. Cells were incubated with low sodium, high sodium, high sodium + FAD286 (100 nM), or high sodium + spironolactone (100 nM). (Number of force measurements: 130 mM: n=29; 150 mM: n=30; 150 mM+FAD: n=27, 150 mM+Spiro: n=29.) **P < 0.01 vs. other groups; Mann-Whitney U test.

Membrane-inserted EnNaC is functional

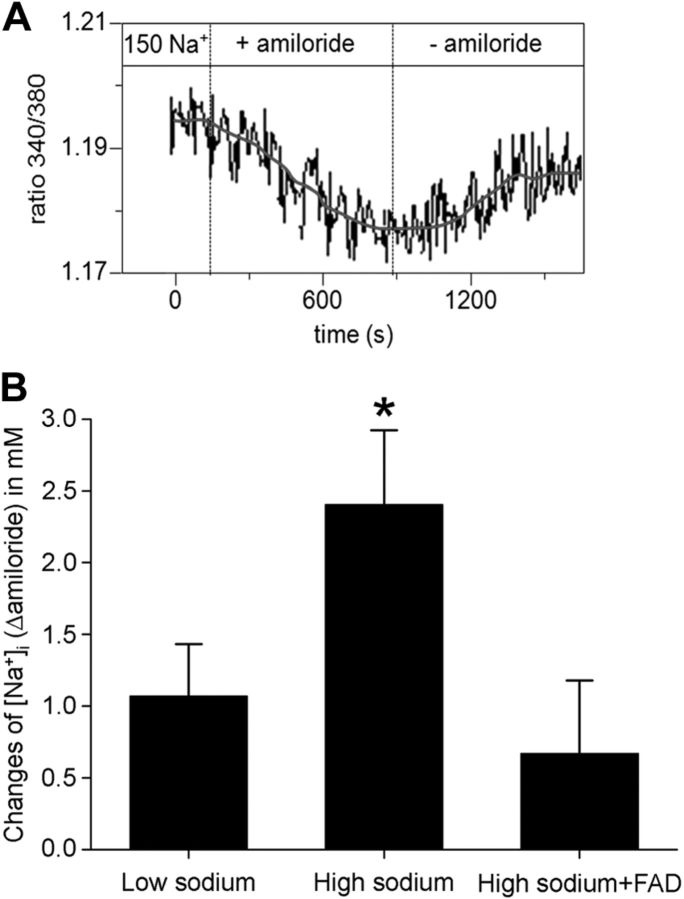

To test whether EnNaC is functionally expressed in the plasma membrane, changes in the amiloride-sensitive intracellular sodium concentration were studied using the sodium-sensitive dye SBFI. At first, intracellular Na+ concentration was determined at the beginning of the experiment. Baseline [Na+]i in EA.hy926 human endothelial cells was 12.2 mM ± 0.72 (mean value; n=29). This value is in agreement with values reported previously (43). Intracellular Na+ concentration was measured every 10 s during perfusion with low sodium, high sodium, or high sodium + FAD286. Figure 7 shows that, in aldosterone-free conditions, addition of amiloride to the cells bathed in high-sodium concentrations changed [Na+]i slightly more (Δ2.4±0.50 mM) than in cells bathed in low sodium (Δ 1.1±0.35 mM), both under aldosterone-free conditions (n=19; P<0.05).

Figure 7.

Measurement of intracellular Na+ concentration. Endothelial cells were perfused with 150 mM Na+ (high sodium) for 30 min, and intracellular Na+ concentrations were determined with the sodium-sensitive dye SBFI (Invitrogen). Amiloride-induced changes of intracellular Δ[Na+]amiloride were recorded. A) Representative experiments in high sodium are shown. Amiloride (10 μM) applied for ∼10 min induces a significant decrease of fluorescence intensity. On amiloride washout, fluorescence intensity recovers and reaches a plateau after ∼5 min. B) Acute exposure to high sodium significantly increases Δ[Na+] from 1.1 ± 0.35 mM (130 mM perfusion) to 2.4 ± 0.50 mM. Inhibition of the endogenous aldosterone synthase CYP11B2 with FAD286 prevents the effect (0.7±0.49 mM). *P ≤ 0.01 vs. other groups; 2-sample Student's t test (n=19).

DISCUSSION

Endothelial function/dysfunction relies on the aldosterone-regulated sodium channel EnNaC, for its membrane insertion modifies the mechanical stiffness of endothelial cells (12, 26, 44, 45). Recently, a positive correlation between EnNaC membrane abundance and mechanical stiffness of the cellular cortex was found, namely, the more EnNaC, the stiffer the endothelial cortex (26). In contrast to soft endothelial cells, which increase NO release (45), stiff endothelial cells release reduced amounts of NO, the hallmark of endothelial dysfunction, leading to SECS (11) and increased vascular resistance (12). In the present study, a novel feedforward regulation of EnNaC by sodium is described indicating that high sodium per se increases cellular EnNaC, as well as abundance of functional plasma membrane EnNaC. An endogenous aldosterone release from endothelial cells and sodium-sensitive MR regulation might be the link for this independent and local mechanism of EnNaC regulation.

Compared to kidney ENaC, the number of endothelial ENaC is rather low. In patch-clamp studies of principal collecting duct cells 3–6 channels/μm2 could be found (46, 47). In contrast, with immunofluorescence-based methods in endothelial cells, only 0.1–0.2 channels/μm2 were detected (this study). The relatively small number of channels in the endothelial membrane together with the fact that vascular endothelium is a leaky barrier, leads to the assumption that EnNaC probably plays only a minor role in overall net Na+ transport across the endothelium. Wang et al. (15) demonstrated that EnNaC possesses similar properties as epithelial ENaC. It has an open probability of 0.4 and an average conductance of ∼5 pS. Nevertheless, it could be shown that the application of amiloride does increase the resistance of an endothelial monolayer, which most likely can be attributed to the functional expression of EnNaC (25). In the present study, an amiloride-sensitive Na+ influx into endothelial cells could be detected with a Na+-sensitive dye, which was found increased under high Na+ conditions, indicating an increased activity of EnNaC. Although EnNaC is rarely expressed in vascular endothelium compared to epithelia, it is likely that endothelial cells have the ability to transport Na+ from the lumen of the blood vessel into the interstitium along a transcellular pathway, as long as an appropriate electrochemical driving force is provided. Possibly, sodium influx via EnNaC triggers conformational changes within the cortical web of endothelial cells and, thus, modifies the nanomechanical cell properties.

EnNaC-mediated endothelial stiffening possibly occurs via interaction of the C terminus of the α-ENaC subunit with F-actin in the cortical cytoskeleton (48, 49). By increasing the number of EnNaC in the plasma membrane, interactions with proteins of the cortical web increase, thus stiffening the cell cortex. An increased membrane abundance of functional EnNaC enhances sodium influx into the cell. Thus, high sodium apparently stabilizes F-actin by conformational changes e.g., strengthening the intersubunit contacts of the protein (50). Therefore, it is not only the physical presence of EnNaC in the endothelial membrane but rather its functional activity (sodium influx), which influences cell mechanics.

It has been suggested that cardiovascular dysfunction, due to high-salt intake, is also related to impaired NO synthesis by the endothelium (12, 51, 52). Li et al. (53) reported that a small increase in sodium concentration per se suppresses eNOS activity. It is tempting to speculate that with high salt loads (possibly due to increased salt intake or loss of water) endothelial cells stiffen, with the result that NO release decreases. Furthermore, an active EnNaC is likely to inhibit eNOS phosphorylation via a blockade of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway leading to reduced NO release (13). Recently, it was reported that the expression of EnNaC in the endothelium is increased in rats on a high-sodium diet, despite low plasma aldosterone (24). ENaC expression depends on the presence of aldosterone, which is also synthesized at extra-adrenal sites, as shown by a number of studies (30–34), including the present one. Further, the functional expression of the key enzyme of the aldosterone synthesis pathway, CYP11B2 was demonstrated in vascular endothelium, which implies that this tissue has the ability to “locally” synthesize aldosterone de novo. This is an important prerequisite to regulate the expression and membrane insertion of EnNaC, independent of systemic plasma aldosterone concentrations. Taken together, there appears to be a link between extracellular sodium and cell mechanics, namely, that endogenously produced aldosterone allows the local regulation of EnNaC via the mineralocorticoid receptor signaling pathway. We hypothesize that increasing sodium concentrations in the presence of endogenous aldosterone are the feedforward stimulus rise the number of EnNaC molecules in the plasma membrane enabling the cell to adapt its mechanical properties within minutes.

This mechanism might be a relic of former times (∼3,000,000 yr ago) when salt was a rare commodity and daily sodium intake was less than 1 g. In such a situation, it was crucial to have a mechanism that enables ingested sodium to be effectively retained into the body, where it is stored, osmotically inactive, in extracellular matrices (54, 55). With agriculture and farming instead of collecting and hunting, lifestyle “suddenly” changed some 10,000 yr ago. It became a common practice to preserve food such as bread and meat with salt and as a result salt intake rapidly increased to ∼12 g/d. However, the human body is, from the evolutional and genetic standpoint, still adapted to a very low amount of salt intake, so that this high amount of ingested salt is prone to exceed the renal sodium excretion capacity. In various clinical trials it was shown that high salt intake is related to the development of hypertension, stroke, coronary heart disease, and renal fibrosis (reviewed in ref. 2). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that high-sodium intake can directly damage the vascular system, which might be a slow but severe process (56). As life expectation is now close to 80 yr, the harmful effects of high-salt diets have become increasingly apparent.

The importance of the MR in sodium-induced EnNaC expression was demonstrated by the fact that spironolactone can prevent even the acute effects of sodium. Interestingly, in the complete absence of aldosterone, high sodium concentrations increase the transcription of MR while, in contrast, the EnNaC membrane abundance is reduced. This apparently paradoxical response is in agreement with the observation of Nagase et al. (57) that salt loading decreases serum aldosterone, whereas MR activation in the target tissue is increased.

However, an increase in MR alone is not sufficient to stimulate EnNaC membrane insertion but rather needs in addition the presence of (endogenous) aldosterone. Taken together, both receptor and hormone are needed for EnNaC insertion crucial for the proper function of vascular endothelium (58). Since sodium-mediated EnNaC membrane insertion occurs within minutes, this mechanism refers to the nongenomic action of aldosterone, which triggers the rapid delivery of preformed ENaC molecules to the plasma membrane (59). In contrast, chronically administered high sodium concentrations do not increase EnNaC transcription but augment the cellular EnNaC level and membrane abundance of the channel. Thus, it is postulated that in the long-term, high-sodium concentrations supposably disturb the degradation of EnNaC.

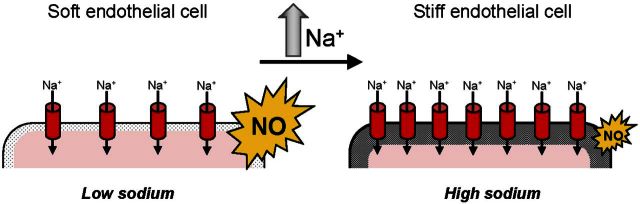

The results described here are in contrast to the well-established view that a high plasma (16, 17) sodium concentration inhibits aldosterone release from the suprarenal glands (1, 60, 61) and in kidney reduces the expression of ENaC via a mechanism called feedback inhibition (62, 63). Recently, consistent with the present results, Morizane et al. (64) observed that chronic salt overload stimulates local and ‘paradox’ aldosterone production in the adrenal gland of Dahl-S rats, a new mechanism that is apparently in contrast to the classical response in kidney. From the present results, it is concluded that in vascular endothelium, an acute increase of extracellular sodium concentration, e.g., due to large dietary sodium intake or a loss of water, can induce a fast aldosterone- and MR-dependent insertion of EnNaC into the plasma membrane. This mechanism might be crucial to find a balance between volume homeostasis (physiological role of the kidney) and effective sodium supply to the interstitial space (physiological role of the endothelium), especially when sodium supply is low. Furthermore, it appears to trigger a physiological response, for it transiently stiffens the cells and reduces NO release, which increases vascular smooth muscle tone and, thus, may prevent any deleterious decrease in arterial blood pressure. If, however, the rise in plasma sodium/aldosterone persists, the stiffness of the endothelial cells remains increased and the release of NO is chronically reduced, a pathophysiological response, which finally leads to a transition from endothelial function to endothelial dysfunction (11), accompanied by structural damage of the endothelium (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Hypothesis to explain how high sodium is linked to cell mechanics. High sodium concentrations trigger ENaC membrane insertion leading to mechanical stiffening of endothelial cells and reduction in NO release most likely via an interaction of endogenously produced aldosterone and the cytosolic mineralocorticoid receptor. This could contribute to the development of the stiff endothelial cell syndrome (11) and endothelial dysfunction.

Taken together, the inhibitory feedback mechanism of sodium on ENaC activity in kidney and the feedforward mechanism of sodium on EnNaC in vascular endothelium could be complementary processes for Na+ homeostasis and blood pressure regulation (16).

Future work should focus on the cloning and sequencing of EnNaC in terms of mutations that have been shown to affect the regulation of ENaC. In addition, the use of mouse models (e.g., aldosterone synthase-knockout, endothelial specific αENaC knockout or MR-knockout) would help to disclose the specific function and regulation of EnNaC in the vascular endothelium in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jürgen Reinhardt (Novartis, Basel, Swizerland) for kind supply of FAD286 and Marianne Wilhelmi and Anja Blanqué for excellent technical assistance. The authors are grateful to Johanna Nedele (Department of Internal Medicine D, University of Münster), Lina Golle for assistance with the qRT-PCR experiments, Anne Wiesinger, and Otto Lindemann (Institute of Physiology II, University of Münster) for further technical advice.

Work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Koselleck OB 63/18, KU 1496/7-1), the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung (2010_A116), Innovative Medical Research (IMF) of the University of Münster (KU 120808), and by the Centre of Excellence (Cells in Motion; CIM), University of Münster.

The authors also thank COST Action TD1002 and COST Action BM 1301 for supporting their networking activities. This paper is dedicated to the late Professor Hugh de Wardener, Imperial College London, who read and commented on a former version of this work.

Footnotes

- AFM

- atomic force microscope

- EC

- endothelial cell

- ENaC

- epithelial sodium channel

- EnNaC

- endothelial sodium channel

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- MR

- mineralocorticoid receptor

- NGS

- normal goat serum

- NO

- nitric oxide

- QD

- quantum dot

- SECS

- stiff endothelial cell syndrome

REFERENCES

- 1. He F. J., Markandu N. D., Sagnella G. A., de Wardener H. E., MacGregor G. A. (2005) Plasma sodium: ignored and underestimated. Hypertension 45, 98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meneton P., Jeunemaitre X., de Wardener H. E., MacGregor G. A. (2005) Links between dietary salt intake, renal salt handling, blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. Physiol. Rev. 85, 679–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown N. J. (2013) Contribution of aldosterone to cardiovascular and renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 9, 459–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fujita T. (2008) Aldosterone in salt-sensitive hypertension and metabolic syndrome. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 86, 729–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lifton R. P., Wilson F. H., Choate K. A., Geller D. S. (2002) Salt and blood pressure: new insight from human genetic studies. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 67, 445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lifton R. P., Gharavi A. G., Geller D. S. (2001) Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 104, 545–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lang F., Gorlach A., Vallon V. (2009) Targeting SGK1 in diabetes. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 13, 1303–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oberleithner H. (2005) Aldosterone makes human endothelium stiff and vulnerable. Kidney Int. 67, 1680–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fels J., Callies C., Kusche-Vihrog K., Oberleithner H. (2010) Nitric oxide release follows endothelial nanomechanics and not vice versa. Pflügers Arch. 460, 915–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fels J., Oberleithner H., Kusche-Vihrog K. (2010) Menage a trois: Aldosterone, sodium, and nitric oxide in vascular endothelium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1802, 1193–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lang F. (2011) Stiff endothelial cell syndrome in vascular inflammation and mineralocorticoid excess. Hypertension 57, 146–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oberleithner H., Riethmuller C., Schillers H., MacGregor G. A., de Wardener H. E., Hausberg M. (2007) Plasma sodium stiffens vascular endothelium and reduces nitric oxide release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 16281–16286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perez F. R., Venegas F., Gonzalez M., Andres S., Vallejos C., Riquelme G., Sierralta J., Michea L. (2009) Endothelial epithelial sodium channel inhibition activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase via phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt in small-diameter mesenteric arteries. Hypertension 53, 1000–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Golestaneh N., Klein C., Valamanesh F., Suarez G., Agarwal M. K., Mirshahi M. (2001) Mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated signaling regulates the ion gated sodium channel in vascular endothelial cells and requires an intact cytoskeleton. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280, 1300–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang S., Meng F., Mohan S., Champaneri B., Gu Y. (2009) Functional ENaC channels expressed in endothelial cells: a new candidate for mediating shear force. Microcirculation 16, 276–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Warnock D. G. (2013) The amiloride-sensitive endothelial sodium channel and vascular tone. Hypertension 61, 952–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warnock D. G., Kusche-Vihrog K., Tarjus A., Sheng S., Oberleithner H., Kleyman T. R., Jaisser F. (2014) Blood pressure, and amiloride-sensitive sodium channels in vascular and renal cells. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 10, 146–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garty H., Palmer L. G. (1997) Epithelial sodium channels: function, structure, and regulation. Phys. Rev. 77, 359–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alvarez de la Rosa D., Canessa C. M., Fyfe G. K., Zhang P. (2000) Structure and regulation of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62, 573–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Warnock D. G. (1998) Liddle syndrome: an autosomal dominant form of human hypertension. Kidney Intern. 53, 18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snyder P. M. (2002) The epithelial Na+ channel: cell surface insertion and retrieval in Na+ homeostasis and hypertension. Endocr. Rev. 23, 258–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McEneaney V., Harvey B. J., Thomas W. (2008) Aldosterone regulates rapid trafficking of epithelial sodium channel subunits in renal cortical collecting duct cells via protein kinase D activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 881–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stockand J. D. (2002) New ideas about aldosterone signaling in epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 282, F559–F576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kakizoe Y., Kitamura K., Ko T., Wakida N., Maekawa A., Miyoshi T., Shiraishi N., Adachi M., Zhang Z., Masilamani S., Tomita K. (2009) Aberrant ENaC activation in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. J. Hypertens. 27, 1679–1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Korte S., Wiesinger A., Straeter A. S., Peters W., Oberleithner H., Kusche-Vihrog K. (2011) Firewall function of the endothelial glycocalyx in the regulation of sodium homeostasis. Pflügers Arch. 463, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jeggle P., Callies C., Tarjus A., Fassot C., Fels J., Oberleithner H., Jaisser F., Kusche-Vihrog K. (2013) Epithelial sodium channel stiffens the vascular endothelium in vitro and in Liddle mice. Hypertension 61, 1053–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kusche-Vihrog K., Jeggle P., Oberleithner H. (2014) The role of ENaC in vascular endothelium. Pflügers Arch. 10, 146–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Caprio M., Newfell B. G., la Sala A., Baur W., Fabbri A., Rosano G., Mendelsohn M. E., Jaffe I. Z. (2008) Functional mineralocorticoid receptors in human vascular endothelial cells regulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and promote leukocyte adhesion. Circ. Res. 102, 1359–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wildling L., Hinterdorfer P., Kusche-Vihrog K., Treffner Y., Oberleithner H. (2009) Aldosterone receptor sites on plasma membrane of human vascular endothelium detected by a mechanical nanosensor. Pflügers Arch. 458, 223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gomez-Sanchez C. E., Zhou M. Y., Cozza E. N., Morita H., Foecking M. F., Gomez-Sanchez E. P. (1997) Aldosterone biosynthesis in the rat brain. Endocrinology 138, 3369–3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang B. S., White R. A., Jeng A. Y., Leenen F. H. (2009) Role of central nervous system aldosterone synthase and mineralocorticoid receptors in salt-induced hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 296, R994–R1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gomez-Sanchez E. P., Ahmad N., Romero D. G., Gomez-Sanchez C. E. (2004) Origin of aldosterone in the rat heart. Endocrinology 145, 4796–4802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takeda R., Hatakeyama H., Takeda Y., Iki K., Miyamori I., Sheng W. P., Yamamoto H., Blair I. A. (1995) Aldosterone biosynthesis and action in vascular cells. Steroids 60, 120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delcayre C., Silvestre J. S., Garnier A., Oubenaissa A., Cailmail S., Tatara E., Swynghedauw B., Robert V. (2000) Cardiac aldosterone production and ventricular remodeling. Kidney Int. 57, 1346–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Funder J. W. (2004) Cardiac synthesis of aldosterone: going, going, gone.? Endocrinology 145, 4793–4795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Takeda Y., Miyamori I., Inaba S., Furukawa K., Hatakeyama H., Yoneda T., Mabuchi H., Takeda R. (1997) Vascular aldosterone in genetically hypertensive rats. Hypertension 29, 45–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Edgell C. J., McDonald C. C., Graham J. B. (1983) Permanent cell line expressing human factor VIII-related antigen established by hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80, 3734–3737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kusche-Vihrog K., Urbanova K., Blanque A., Wilhelmi M., Schillers H., Kliche K., Pavenstadt H., Brand E., Oberleithner H. (2011) C-reactive protein makes human endothelium stiff and tight. Hypertension 57, 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abramoff M. D., Magelhaes P. J., Ram S. J. (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Intl. 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kusche-Vihrog K., Sobczak K., Bangel N., Wilhelmi M., Nechyporuk-Zloy V., Schwab A., Schillers H., Oberleithner H. (2008) Aldosterone and amiloride alter ENaC abundance in vascular endothelium. Pflügers Arch. 455, 849–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maier L. S., Pieske B., Allen D. G. (1997) Influence of stimulation frequency on [Na+]i and contractile function in Langendorff-perfused rat heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 273, H1246–H1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oberleithner H., Riethmüller C., Ludwig T., Shahin V., Stock C., Schwab A., Hausberg M., Kusche K., Schillers H. (2006) Differential action of steroid hormones on human endothelium. J. Cell Sci. 119, 1926–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cutaia M., Davis R., Parks N., Rounds S. (1996) Effect of ATP-induced permeabilization on loading of the Na+ probe SBFI into endothelial cells. J. Appl. Physiol. 81, 509–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kusche-Vihrog K., Callies C., Fels J., Oberleithner H. (2009) The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC): mediator of the aldosterone response in the vascular endothelium? Steroids 75, 544–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oberleithner H., Callies C., Kusche-Vihrog K., Schillers H., Shahin V., Riethmuller C., MacGregor G. A., de Wardener H. E. (2009) Potassium softens vascular endothelium and increases nitric oxide release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 2829–2834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Palmer L. G., Frindt G. (1988) Conductance and gating of epithelial Na-channels from rat cortical collecting tubule. J. Gen. Physiol. 92, 121–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rossier B. C. (2002) Hormonal regulation of the epithelial sodium channel ENaC: N or P(o)? J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 67–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mazzochi C., Bubien J. K., Smith P. R., Benos D. J. (2006) The carboxyl terminus of the α-subunit of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel binds to F-actin. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6528–6538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gorelik J., Zhang Y., Sanchez D., Shevchuk A., Frolenkov G., Lab M., Klenerman D., Edwards C., Korchev Y. (2005) Aldosterone acts via an ATP autocrine/paracrine system: the Edelman ATP hypothesis revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 15000–15005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oda T., Makino K., Yamashita I., Namba K., Maeda Y. (2001) Distinct structural changes detected by X-ray fiber diffraction in stabilization of F-actin by lowering pH and increasing ionic strength. Biophys. J. 80, 841–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ni Z., Vaziri N. D. (2001) Effect of salt loading on nitric oxide synthase expression in normotensive rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 14, 155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bragulat E., de La S. A., Antonio M. T., Coca A. (2001) Endothelial dysfunction in salt-sensitive essential hypertension. Hypertension 37, 444–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li J., White J., Guo L., Zhao X., Wang J., Smart E. J., Li X. A. (2009) Salt inactivates endothelial nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells. J. Nutr. 139, 447–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Titze J., Krause H., Hecht H., Dietsch P., Rittweger J., Lang R., Kirsch K. A., Hilgers K. F. (2002) Reduced osmotically inactive Na storage capacity and hypertension in the Dahl model. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 283, F134–F141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Titze J., Machnik A. (2010) Sodium sensing in the interstitium and relationship to hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 19, 385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sanders P. W. (2009) Vascular consequences of dietary salt intake. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 297, F237–F243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nagase M., Matsui H., Shibata S., Gotoda T., Fujita T. (2007) Salt-induced nephropathy in obese spontaneously hypertensive rats via paradoxical activation of the mineralocorticoid receptor: role of oxidative stress. Hypertension 50, 877–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Funder J. W. (2006) Mineralocorticoid receptors and cardiovascular damage: it's not just aldosterone. Hypertension 47, 634–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Falkenstein E., Christ M., Feuring M., Wehling M. (2000) Specific nongenomic actions of aldosterone. Kidney Intern. 57, 1390–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Williams G. H., Tuck M. L., Rose L. I., Dluhy R. G., Underwood R. H. (1972) Studies of the control of plasma aldosterone concentration in normal man. 3. Response to sodium chloride infusion. J. Clin. Invest. 51, 2645–2652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takeda Y. (2004) Vascular synthesis of aldosterone: role in hypertension. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 217, 75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fuchs W., Larsen E. H., Lindemann B. (1977) Current-voltage curve of sodium channels and concentration dependence of sodium permeability in frog skin. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 267, 137–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Volk T., Konstas A. A., Bassalay P., Ehmke H., Korbmacher C. (2004) Extracellular Na+ removal attenuates rundown of the epithelial Na+-channel (ENaC) by reducing the rate of channel retrieval. Pflügers Arch. 447, 884–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Morizane S., Mitani F., Ozawa K., Ito K., Matsuhashi T., Katsumata Y., Ito H., Yan X., Shinmura K., Nishiyama A., Honma S., Suzuki T., Funder J. W., Fukuda K., Sano M. (2012) Biphasic time course of the changes in aldosterone biosynthesis under high-salt conditions in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 1194–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]