Abstract

Background

Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.), including japonica and indica, is unarguable the most important crop in Asia as well as worldwide. However, a decisive conclusion of its origination and domestication processes are still lacking. Nowadays, the ever-increasing high-throughput sequencing data of numerous rice samples have provided us new opportunities to get close to the answer of these questions.

Results

By compiling 296 whole-genome sequenced rice cultivars and 39 diverse wild rice, two types of domesticated regions (DR-I and DR-II) with strong selective sweep signals between different groups were detected. DR-I regions included 28 blocks which significantly differentiated between japonica and indica subspecies, while DR-II regions were consisted of another 28 blocks which significantly differentiated between wild and cultivated rice, each covered 890 kb and 640 kb, respectively. In-depth analysis suggested that both DR-Is and DR-IIs could have originated from Indo-China Peninsula to southern China, and DR-IIs might be introgressed from indica to japonica. Functional bias with significant positive selection has also been detected in the genes of DR-I, suggesting important role of the selective sweep in differentiation of japonica and indica.

Conclusions

This research promoted a new possible model of the origin of the cultivated rice that DR-Is in japonica and indica maybe independently originated from the divergent wild rice in the Indo-China Peninsula to southern China, and then followed by frequent introgression. Genes with significant positive selection and biased functions were also detected which could play important roles in rice domestication and differentiation processes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3702-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: japonica, indica, Wild rice, Domestication, Resequencing, Functional genes

Background

As one of the most important cereal grains, rice has been used as a major food source for more than half of the world’s population [1]. Asian cultivated rice is divided into two subspecies, Oryza sativa ssp. japonica and Oryza sativa ssp. indica. The japonica varieties are adapted to more temperate climates, whereas most indica varieties are generally adapted to tropical lowland cultivation [2]. The distinction between the two rice subspecies has been recognized in China since at least the Han dynasty [3].

However, the origin(s) of the two subspecies has long been under scrutiny and debate, particularly on whether the two subspecies were derived from a single or multiple domestications [4]. Numerous studies have suggested that the two subspecies of indica and japonica were probably independently domesticated from different isolates of the wild rice, Oryza rufipogon [5, 6], which was then followed by further differentiation [7]. Londo et al. believed that indica might have originated from a region south of the Himalaya mountain range, whereas japonica originated from wild rice in southern China [8]. On the other hand, Molina et al. reported that Asian rice might have been domesticated from a single origin [9]. A more recent study supports the viewpoint of a single origin, indicating that Asian rice cultivars might have been domesticated from southern China [10]. The comprehensive and deeper survey of the genetic basis of domestication may contribute to improved domestication strategies of organisms and provide novel approaches in deciphering the process of domestication [11–13]. To date, the debate on the origin of Asian rice cultivars remains elusive, thus requiring additional evidence to resolve this issue.

Ongoing works have already characterized a large number of genes, such as Sub1A [14], S-5 [15], and NRT1.1B [16], which were demonstrated to be involved in differentiation between the two subspecies. Similarly, some other genes are related to domestication from wild to cultivated rice, including Bh4 [17], PROG1 [18] and sh4 [19]. It is essential to utilize these genes in distinguishing the two subspecies or wild rice from rice cultivars. However, information on the mechanism underlying the differences in morphological, physiological, and biochemical features, as well as some other aspects between the two subspecies or wild rice and cultivated rice is limited. Moreover, the agronomic traits may be controlled by multiple genes, which were difficult to be identified [20]. Therefore, additional studies that aim to identify genes that are involved in the domestication of rice at the whole-genome scale using new methods such as whole genome sequencing technology are warranted [10, 20].

Recently, a batch of 3,000 rice accessions have been fully sequenced with high coverage [21], which provided unprecedented opportunities to explore the differentiation between indica and japonica via genomic approaches. By characterizing the two types of domesticated regions according to selection signatures and subsequent phylogenetic analysis, we delimited the potential zone for origins of the two subspecies, that is, the two subspecies may have a common origin in the Indo-China Peninsula. In addition, significant positive selection and particular genes that possibly control important morphological traits between cultivars and wild rice, as well as differentiation between indica and japonica were identified in these two types of domesticated regions, which suggests that selective sweep with significant positive selection may serve as the driving force for the differentiation of the two rice subspecies.

Results

Selection of the rice accessions

Although the 3,000 rice genomes dataset [21] provides an unprecedented resource for detecting the selective sweep regions in rice cultivars, most of which have low-coverage or inadequate sequencing depths that are difficult to employ in the high-resolution detection analysis due to the frequent coverage gaps. Therefore, 330 cultivars with ≥15× sequencing depths were downloaded from the 3,000 samples (Additional file 1: Table S1). To detect the regions with significant differentiation between japonica and indica, only those cultivars with significant differentiation that was detected by diversity calculation and PCA were retained (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Table S2 see Methods). Finally, 296 out of the 330 rice cultivars, including 154 indica and 142 japonica cultivars, from 45 different countries (or regions), were used for further analysis, which have 23.8× average sequencing depth (ranging from 15.0× to 51.1×; Additional file 1: Table S1). The other 34 cultivars were removed due to the potential genetic admixtures of these two subspecies (Additional file 1: Table S1). And the retained cultivars exhibited scattered geographic distribution. About 1/3 of these cultivars were collected from China and India, both of which are geographically larger. Another 1/3 were from countries in Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Burma, Cambodia and so on. The last 1/3 were from other countries, such as Japan, South Korea and so on.

In addition, the sequences of 39 diverse wild rice O. rufipogon or O. nivara (also referred to annual of O. rufipogon) accessions, which were believed to be the immediate progenitor of the Asian cultivated rice of O. sativa, were collected from previous reports [10] (Additional file 1: Table S3). These sequences have 11× sequencing depth on average (ranging from 4.0× to 68.6×). On the other hand, the whole-genome sequences of 20 African rice O. glaberrima accessions, which are closely related to O. sativa and O. rufipogon, were downloaded at a 42.0× average sequencing depth (ranging from 5.9× to 120.3×; Additional file 1: Table S3) as outgroups for further analysis.

Nucleotide diversity/divergence within or between these two subspecies

After trimming and removing low-quality bases, the clean reads of 296 Asian cultivated rice, 39 wild rice, and 20 Africa cultivated rice accessions were mapped to the Nipponbare reference genome. Then, joint SNP calling and genotyping of the sequenced samples were performed (see Methods). After stringent filtering, a total of 23,147,437 SNPs across all the 355 various rice samples were called and used to estimate diversity among samples or divergence among groups.

Based on the SNP data, π was estimated at 0.00196 within japonica and 0.00265 within indica groups (Additional file 1: Figure S2), which were higher than that within japonica (0.0006) and indica (0.0016) that were estimated in 517 Chinese indica and japonica landraces [22]. These discrepancies may be due to (i) higher genetic diversity in the worldwide cultivars than that only in Chinese landraces; (ii) an underestimation of the genetic diversity in these 517 Chinese landraces caused by the low-coverage sequencing depth (average 1× for each sample). D xy between indica and japonica was about 0.00617 in our selected samples (Additional file 1: Figure S2), suggesting a significant differentiation between these two subspecies, which also had been confirmed by the PCA analysis. As expected, the diversity within these wild rice accessions was about 0.0067 (Additional file 1: Figure S2), which was significantly higher than that in japonica or indica, suggesting the strong bottleneck during the domestication that has also been reported by other studies [10, 23, 24]. As is known, the short-read sequencing technology could generate massive erroneous SNP calls if not properly handled. However, it was less likely for those false signals to mimic the truly differentiated SNPs. Such erroneous calls would distribute more randomly, both in japonica and in indica, which rarely resulted in low diversities within each subspecies. Furthermore, we did not observe any inflation in the estimated diversities, or any significant departure in the PCA analysis. This implies a conservative SNP call set, given the high coverage dataset and the stringent criteria used in this study.

Detection of regions that underwent selective sweep

The large SNP data set detected in our samples provides an opportunity to identify artificial selected regions by comparing polymorphism levels in these cultivated and wild rice accessions. The selective signature from domestication with selective sweep includes a reduction in nucleotide diversity/divergence and altered allele frequency in these domestication loci. As mentioned above, the average diversity within japonica or indica is about 0.002. Therefore, the value of 0.002 was employed as one cutoff to detect the divergent regions between japonica and indica. Among these divergent regions, only those which have at least 10-fold lower diversity (0.0002) between the two subspecies can be defined as selective sweep regions both in japonica and indica. Compared with previous studies, two advantages can be found in our definition: i) the ten-fold-lower diversity is a more stringent criterion than previous study [10]; ii) by using 0.002, we can easily exclude these regions having very low divergence between these two subspecies and very low diversity within each of the two subspecies, which may not be the result of divergence and selection, instead, caused by sequencing or analytical errors.

Therefore, two types of domesticated regions were detected (Tables 1, 2 and 3): domesticated region type I (defined as DR-I), which have undergone selective sweep within each subspecies (π ≤ 0.0002) but have high divergence between these two subspecies (D xy ≥0.002); domesticated region type II (defined as DR-II), which have low diversity regions shared by both subspecies (not only π ≤ 0.0002 within each subspecies, but also D xy ≤0.0002 between the two subspecies), but have high diversity within the wild rice (π ≥ 0.001) (See Methods for details).

Table 1.

Blocks with selective sweep

| DR-I | DR-II | |

|---|---|---|

| Block numbers | 28 | 28 |

| Average length (kb) | 31.8 | 23 |

| Total length (Mb) | 0.89 | 0.64 |

| Including genes | 163 | 110 |

DR-I, domesticated regions of type I that have undergone selective sweep within each subspecies (π < 0.0002) but have high divergence between these two subspecies (D xy >0.002); DR-II, domesticated regions of type II that have low diversity shared by both subspecies (not only π < 0.0002 within each subspecies, but also D xy <0.0002 between the two subspecies), but have high diversity within the wild rice (π > 0.001)

Table 2.

Genome-wide identification of selective sweep regions with low diversity (π ≤ 0.0002) within each of the two subspecies, respectively, but with high divergence (D xy ≥0.002) between these two subspecies, which were defined as DR-I. Six regions showed slightly higher π values (≥0.0002 but ≤0.0003, flagged by * in this table) because these were merged regions (See methods)

| Chr | Range of the blocks | Length (bp) |

πJap

*105 |

πTro

*105 |

πTem

*105 |

πInd

*105 |

D

Jap-Ind

*105 |

D

Tro-Ind

*105 |

D

Tmp-Ind

*105 |

πWild

*105 |

D

Jap-Wild

*105 |

D

Ind-Wild

*105 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | chr01 | 35499730–35510003 | 10274 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 242 | 246 | 241 | 89 | 178 | 121 |

| 2* | chr01 | 35839043–35890683 | 51641 | 19 | 10 | 13 | 21 | 468 | 478 | 467 | 232 | 320 | 263 |

| 3 | chr02 | 13139975–13160003 | 20029 | 18 | 5 | 6 | 18 | 295 | 305 | 301 | 133 | 209 | 142 |

| 4 | chr02 | 13349983–13360044 | 10062 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 241 | 249 | 246 | 101 | 149 | 131 |

| 5 | chr02 | 14944936–14962544 | 17609 | 15 | 3 | 4 | 14 | 250 | 260 | 252 | 121 | 157 | 145 |

| 6 | chr02 | 27708263–27721727 | 13465 | 11 | 4 | 11 | 14 | 263 | 271 | 263 | 87 | 143 | 145 |

| 7 | chr03 | 1579192–1602557 | 23366 | 16 | 4 | 15 | 14 | 302 | 307 | 311 | 153 | 183 | 193 |

| 8* | chr03 | 2483329–2542460 | 59132 | 16 | 20 | 9 | 25 | 434 | 444 | 435 | 198 | 275 | 239 |

| 9 | chr03 | 2706518–2724355 | 17838 | 13 | 18 | 7 | 18 | 440 | 453 | 440 | 188 | 310 | 210 |

| 10 | chr03 | 2832279–2854311 | 22033 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 16 | 304 | 310 | 306 | 214 | 210 | 243 |

| 11 | chr03 | 2896026–2923841 | 27816 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 321 | 327 | 323 | 151 | 178 | 220 |

| 12* | chr03 | 2997394–3195565 | 198172 | 18 | 11 | 22 | 21 | 578 | 590 | 580 | 260 | 356 | 316 |

| 13 | chr03 | 3479756–3498823 | 19068 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 241 | 245 | 243 | 132 | 180 | 138 |

| 14* | chr03 | 24189350–24230136 | 40787 | 20 | 14 | 28 | 22 | 504 | 511 | 508 | 289 | 341 | 306 |

| 15 | chr03 | 28469725–28489493 | 19769 | 14 | 21 | 7 | 12 | 429 | 437 | 427 | 245 | 327 | 308 |

| 16 | chr04 | 34409908–34420007 | 10100 | 13 | 6 | 15 | 19 | 314 | 316 | 319 | 159 | 216 | 176 |

| 17 | chr04 | 34469603–34500654 | 31052 | 14 | 6 | 16 | 16 | 262 | 264 | 265 | 123 | 169 | 136 |

| 18* | chr05 | 21659599–21670204 | 10606 | 16 | 7 | 25 | 21 | 289 | 295 | 291 | 156 | 177 | 202 |

| 19 | chr05 | 22789981–22800012 | 10032 | 17 | 6 | 16 | 15 | 319 | 328 | 331 | 472 | 379 | 421 |

| 20 | chr05 | 22869880–22880236 | 10357 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 17 | 295 | 305 | 302 | 137 | 155 | 208 |

| 21 | chr05 | 24026607–24070766 | 44160 | 20 | 9 | 35 | 18 | 604 | 614 | 616 | 318 | 438 | 349 |

| 22 | chr05 | 24300403–24330214 | 29812 | 16 | 8 | 13 | 11 | 343 | 356 | 350 | 348 | 346 | 329 |

| 23 | chr05 | 26824033–26840483 | 16451 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 17 | 233 | 243 | 239 | 131 | 172 | 137 |

| 24 | chr07 | 4149981–4163826 | 13846 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 18 | 214 | 220 | 217 | 420 | 365 | 365 |

| 25 | chr07 | 25598750–25620217 | 21468 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 16 | 323 | 327 | 323 | 155 | 219 | 190 |

| 26 | chr09 | 22759164–22771433 | 12270 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 18 | 251 | 258 | 254 | 171 | 164 | 204 |

| 27 | chr09 | 22910542–22930021 | 19480 | 14 | 8 | 11 | 18 | 345 | 356 | 349 | 242 | 251 | 256 |

| 28* | chr10 | 21289972–21400480 | 110509 | 18 | 10 | 12 | 23 | 517 | 534 | 521 | 250 | 336 | 263 |

| Average | 31829 | 13 | 7 | 11 | 17 | 344 | 352 | 347 | 203 | 247 | 227 | ||

Table 3.

Genome-wide identification of the DR-II type selective sweep regions with low diversity (π ≤ 0.0002) within cultivars, but high diversity (π >0.001) in wild rice

| Chr | Rang of blocks | Length (bp) |

πJap

*105 |

πInd

*105 |

DJap-Ind

*105 |

πCultivar

*105 |

πWild

*105 |

DJap-Wild

*105 |

DInd-Wild

*105 |

DCul-Wild

*105 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | chr01 | 8645929–8660126 | 14198 | 1 | 18 | 16 | 13 | 118 | 104 | 108 | 106 |

| 2 | chr03 | 26199939–26210003 | 10065 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 141 | 140 | 144 | 142 |

| 3 | chr04 | 25959995–26040007 | 80013 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 181 | 228 | 229 | 229 |

| 4 | chr04 | 26089892–26100078 | 10187 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 155 | 250 | 249 | 249 |

| 5 | chr04 | 26229998–26260103 | 30106 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 230 | 327 | 325 | 326 |

| 6 | chr04 | 26359991–26370003 | 10013 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 125 | 168 | 166 | 167 |

| 7 | chr04 | 26789966–26810053 | 20088 | 10 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 155 | 251 | 247 | 249 |

| 8 | chr04 | 26949945–26970083 | 20139 | 9 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 141 | 191 | 190 | 190 |

| 9 | chr04 | 27009995–27060009 | 50015 | 7 | 20 | 17 | 16 | 286 | 360 | 356 | 358 |

| 10 | chr04 | 32529159–32540000 | 10842 | 18 | 13 | 16 | 16 | 109 | 104 | 123 | 114 |

| 11 | chr04 | 33889971–33900005 | 10035 | 15 | 10 | 20 | 16 | 173 | 228 | 222 | 225 |

| 12 | chr04 | 33979989–33990038 | 10050 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 14 | 100 | 135 | 145 | 140 |

| 13 | chr04 | 34219891–34249999 | 30109 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 11 | 277 | 316 | 319 | 318 |

| 14 | chr05 | 29729953–29740204 | 10252 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 115 | 115 | 103 | 109 |

| 15 | chr07 | 2739991–2770008 | 30018 | 15 | 13 | 18 | 16 | 406 | 456 | 451 | 453 |

| 16 | chr07 | 2799992–2810002 | 10011 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 262 | 311 | 305 | 308 |

| 17 | chr07 | 2879923–2910069 | 30147 | 14 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 280 | 437 | 432 | 434 |

| 18 | chr07 | 2979996–2991842 | 11847 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 140 | 104 | 105 | 105 |

| 19 | chr07 | 3096102–3109999 | 13898 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 110 | 116 | 108 | 112 |

| 20 | chr07 | 3699995–3710053 | 10059 | 12 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 364 | 394 | 396 | 395 |

| 21 | chr07 | 3759873–3790006 | 30134 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 264 | 273 | 272 | 273 |

| 22 | chr07 | 4019981–4030093 | 10113 | 12 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 138 | 131 | 124 | 127 |

| 23 | chr07 | 4070000–4090006 | 20007 | 9 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 236 | 256 | 252 | 254 |

| 24 | chr08 | 23749999–23770091 | 20093 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 246 | 269 | 263 | 266 |

| 25 | chr08 | 23809970–23860036 | 50067 | 9 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 549 | 500 | 501 | 501 |

| 26 | chr08 | 23919999–23940003 | 20005 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 206 | 283 | 282 | 283 |

| 27 | chr08 | 23989975–24040080 | 50106 | 7 | 14 | 11 | 11 | 273 | 315 | 312 | 313 |

| 28 | chr12 | 24930000–24950016 | 20017 | 13 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 168 | 124 | 121 | 122 |

| Average | 22951 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 213 | 247 | 246 | 246 | ||

DR-I showed that differentiation has already occurred in these wild rice, and selective sweep was independently imposed on the domestication of indica or japonica, respectively. Therefore, the indica-japonica differentiation was driven not only by genetic drifts or possible natural selection of wild rice, but also by artificial selection of cultivated rice. The artificial selection should be much more powerful in accelerating the differentiation progress. For this type of domesticated regions, a total of 28 blocks, including about 890 kb of DNA (average: 31.8 kb; ranging from 10 kb to 198 kb) and 163 genes, were detected (Tables 1 and 2). Meanwhile, since japonica had been subdivided into temperate japonica and tropical japonica [25, 26], π within temperate japonica and tropical japonica, and D xy between temperate japonica and indica and tropical japonica and indica were calculated (Table 2). All the data showed a similar result, suggesting that the DR-I regions were conserved in temperate japonica and tropical japonica, and divergent between temperate japonica and indica or tropical japonica and indica.

For DR-II, normal diversity was detected within these wild rice accessions (π ≥ 0.001), whereas very low diversity was detected not only within each subspecies (π ≤ 0.0002), but also between the two subspecies (D xy ≤ 0.0002), suggesting that selective sweep was simultaneously imposed on both indica and japonica, and these overlapping DR-IIs may have originated only once or as a result of selection and subsequent introgression from one subspecies to another. For this type of domesticated region, a total of 28 blocks, including about 640 kb genomic length (average: 23.0 kb, ranging from 10 kb to 80 kb), was detected (Tables 1 and 3).

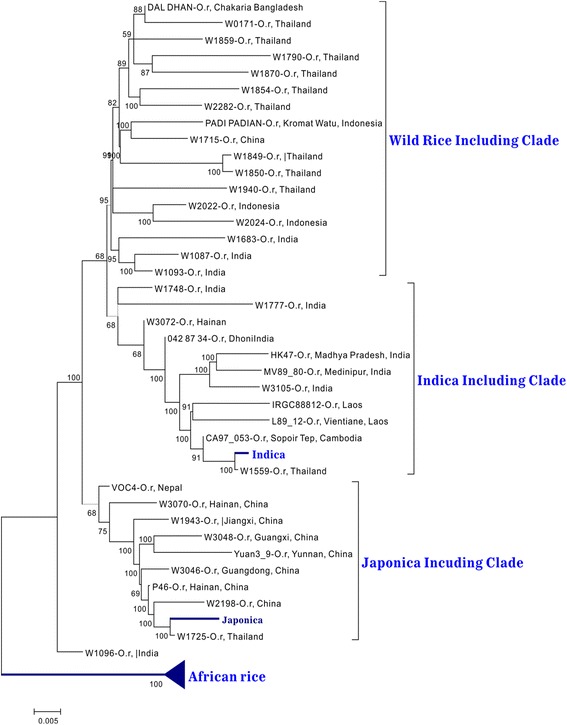

Origin of DR-I

When using the SNPs of DR-I to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree, as expected, all japonica or indica samples clustered together within its own clade, respectively, whereas the japonica clade was distantly located from the indica clade (Fig. 1), which was consistent with the results of PCA analysis that the japonica varieties clearly segregate from the indica individuals (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Furthermore, Tajima’s D and Fst statistics also indicated significant differences of the genetic structure between japonica and indica populations in the DR-I region (Table 4). On the other hand, some wild rice accessions were clustered within the japonica or indica clade, respectively, and some wild rice accessions were scattered outside the two cultivated rice clades, which was also consistent with the findings of previous studies [10].

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the 28 DR-I blocks. The low depth wild rice (whole genome depth <4) were not used in this tree

Table 4.

Results of the analysis by Tajima’s D and Fst statistics between the japonica and indica populations in the DR-I region

| Chr | Range of the blocks | Tajima’s D | Fst

(Jap vs Ind) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jap. | Ind. | Cultivar | ||||

| 1 | chr01 | 35499730–35510003 | −2.344** | −2.319** | 2.564** | 0.93668** |

| 2 | chr01 | 35839043–35890683 | −2.284** | −2.388** | 1.470 | 0.88126** |

| 3 | chr02 | 13139975–13160003 | −1.971** | −1.896 | 1.050 | 0.93705** |

| 4 | chr02 | 13349983–13360044 | −1.940** | −2.265** | 0.953 | 0.93638** |

| 5 | chr02 | 14944936–14962544 | −1.871** | −1.518 | 1.551 | 0.8978** |

| 6 | chr02 | 27708263–27721727 | −1.921** | −1.917** | 2.404** | 0.94298** |

| 7 | chr03 | 1579192–1602557 | −1.794 | −2.420** | 1.862* | 0.90987** |

| 8 | chr03 | 2483329–2542460 | −2.171** | −1.616 | 1.587* | 0.93704** |

| 9 | chr03 | 2706518–2724355 | −2.379** | −2.458** | 1.533* | 0.84626** |

| 10 | chr03 | 2832279–2854311 | −2.412** | −2.235* | 1.182 | 0.58542 |

| 11 | chr03 | 2896026–2923841 | −2.343** | −2.108** | 1.708* | 0.90956** |

| 12 | chr03 | 2997394–3195565 | −2.220** | −1.027 | 2.526** | 0.94684** |

| 13 | chr03 | 3479756–3498823 | −2.313** | −0.066 | 2.738** | 0.9228** |

| 14 | chr03 | 24189350–24230136 | −2.058** | −2.162** | 1.219 | 0.92474** |

| 15 | chr03 | 28469725–28489493 | −2.303** | −1.961** | 1.236 | 0.8877** |

| 16 | chr04 | 34409908–34420007 | −2.097** | −1.729 | 2.262* | 0.91761** |

| 17 | chr04 | 34469603–34500654 | −1.915** | −2.145** | 1.701* | 0.93408** |

| 18 | chr05 | 21659599–21670204 | −1.757 | −2.137** | 0.900 | 0.89436** |

| 19 | chr05 | 22789981–22800012 | −1.857 | −2.009** | 2.331** | 0.91203** |

| 20 | chr05 | 22869880–22880236 | −1.993** | −2.020** | 2.582** | 0.85427** |

| 21 | chr05 | 24026607–24070766 | −2.116** | −1.458 | 2.510** | 0.74986** |

| 22 | chr05 | 24300403–24330214 | −2.017** | −2.275** | 2.936** | 0.94534** |

| 23 | chr05 | 26824033–26840483 | −1.731 | −1.795 | 2.738** | 0.93111** |

| 24 | chr07 | 4149981–4163826 | −1.766 | −1.686 | 2.518** | 0.92099** |

| 25 | chr07 | 25598750–25620217 | −2.310** | −2.049** | 2.955** | 0.89888** |

| 26 | chr09 | 22759164–22771433 | −2.131** | −2.444** | 0.349 | 0.93668** |

| 27 | chr09 | 22910542–22930021 | −1.892 | −2.106** | 2.634** | 0.88126** |

| 28 | chr10 | 21289972–21400480 | −2.120** | −1.634 | 2.594** | 0.93705** |

*and **indicate P-value < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively

In these 28 DR-I blocks, the average diversity was 0.00013 (ranging from 0.00003 to 0.00020) within japonica and 0.00017 (ranging from 0.00011 to 0.00025) within indica (Table 2). However, the average divergence between these two groups was 0.0034, which was 11- to 101-fold higher (~27-fold on average) than the diversity within each group (Table 2), suggesting significant differentiation between indica and japonica in these regions. The average diversity is ~15-fold lower within japonica and ~16-fold lower within indica than their corresponding genome-wide diversity, suggesting strong selection with selective sweep on these regions. On the other hand, in these blocks, significantly positive correlations were displayed either in the diversity within indica vs. japonica, or D ind-jap vs. πjap or πind, or D jap-wild and D ind-wild (Additional file 1: Figure S3). This was consistent with the possibility that japonica and indica may have undergone strong artificial selection from different isolates of the wild rice O. rufipogon during domestication at least in these domesticated blocks.

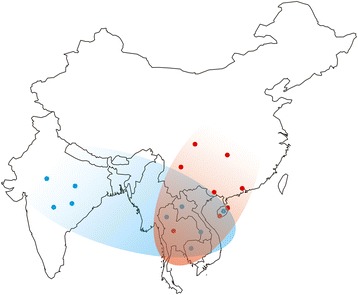

For this reason, a phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using SNPs of the 28 DR-Is to determine which wild rice was more similar to the 28 domesticated blocks that were fixed or near fixed in japonica or indica, respectively. Similar to the findings of previous studies [10], four clear clades were detected, including the African rice clade (also as an outgroup clade), japonica clade with some O. rufipogon accessions, indica clade with some O. rufipogon accessions, and an independent O. rufipogon clade (Fig. 1). All japonica or indica samples were clustered together, whereas all japonica samples were far from all of these indica samples, which matched the PCA result that the japonica varieties clearly segregated from the other groups, suggesting that, at least in these 28 DR-I regions, these two subspecies were probably independently domesticated from different wild rice isolates. Interestingly, the wild rice accessions with the highest similarity to japonica varieties were W1725, W2198, P46 and W3046 (Fig. 1), which were collected from Thailand to Southern China, suggesting that these japonica domesticated regions may have independently originated from the regions of Southern China [10, 27] to the Indo-China Peninsula. On the other hand, the wild rice accessions with the highest similarity to indica were W1559, CA97, L89_12 and IRGC88812, all of which were collected from Indo-China Peninsula, suggesting that these indica domesticated regions may have independently originated from the regions of Indo-China Peninsula. Therefore, the Indo-China Peninsula might be the overlapping place with the closest wild relatives both for japonica and indica.

Due to limited sampling size of wild rice, one possible explanation for the topology of the phylogenetic tree was that the DR-Is are retained by frequent introgression from cultivars to some wild rice. To test this hypothesis, more wild rice samples are necessary for further investigation of the origin of these domesticated regions. We expect if most other wild rice accessions have a similar pattern with above regions, then we can exclude the introgression from cultivars to wild rice in these two regions. Conversely if there were a variety of wild rice accessions exhibiting dissimilar pattern in these two regions, then introgression from cultivars to wild rice may have an impact in our selected wild rice samples. Then, more than 400 whole-genome sequenced wild rice samples were collected to enlarge the sample panel, mostly having low sequence depth (~1×) (Additional file 1: Table S4). Additional file 1: Table S5 repeatedly shows that the wild rice accessions from the Indo-China Peninsula (e.g., W1725 and W1506 from Thailand) or Southern China (e.g., W3093, P46 and W3040) have the highest identity to the genotype of japonica, whereas most of the wild rice accessions from the Indo-China Peninsula (e.g., W1559, W1086 and W1930) have the highest identity to the genotype of indica. This is consistent with the above result that, at least in these 28 DR-I regions, the closest wild relatives for japonica and indica have the overlapping place in Indo-China Peninsula, suggesting that both of the two domesticated subspecies may have a common place of the origin.

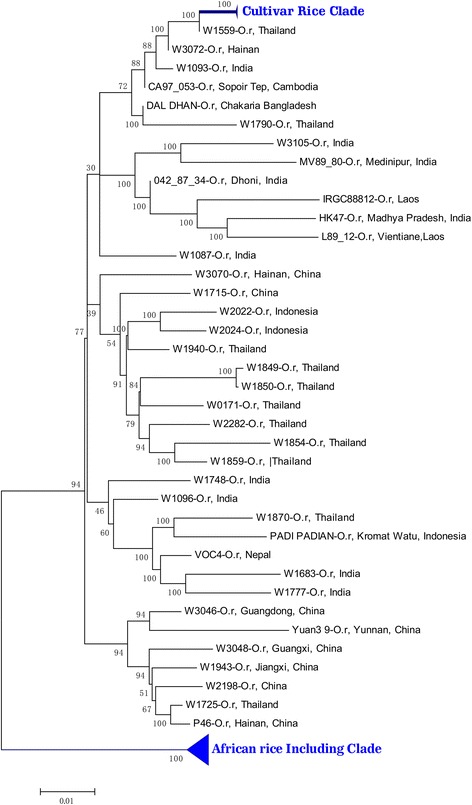

Origin of DR-II

In the 28 DR-II blocks, the average diversity was ~0.0001 either within japonica or indica, even in all of these cultivars, which was about 21-fold (from 6.1 to168-fold) lower than that of wild rice accessions (Table 3), suggesting strong selective sweep both in indica and japonica accessions. This result also suggested that these 28 DR-II blocks should have a common origin and subsequently introgressed from one subspecies to another [10]. The diversity in these regions within japonica, indica, or both was significantly lower than the diversity in the 28 DR-I blocks within japonica (t-test, P = 0.011) or indica (t-test, P < 0.0001), suggesting that the DR-I blocks may be independently fixed in indica or japonica prior to the fixation of the DR-II blocks.

A phylogenetic tree was also reconstructed using the SNPs from the 28 DR-II blocks. As expected, all japonica and indica samples were clustered together as a cultivar clade (Fig. 2), which was different from the topology of the DR-Is, in that tree japonica samples were distantly located from these indica samples and in different clades. The wild rice with the highest similarity to japonica and indica in this tree was also the wild rice of W1559, which had the highest similarity only to indica but not japonica samples in DR-Is, suggesting that these 28 DR-II blocks might have introgressed from indica to japonica.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the 28 DR-II regions

To further investigate the direction of introgression in these DR-IIs, more whole-genome sequenced wild rice samples, including those with low depth, were used as earlier described. The wild rice accessions of W1086 (India), W0178 (Thailand), W1090 (India), CA97_053 (Cambodia), and W0639 (Burma) (Additional file 1: Table S6) have the highest identity to DR-IIs in both indica and japonica. On the other hand, all these wild rice accessions were clustered within the indica-type wild rice clade in the phylogenetic tree. This result further suggested that the 28 DR-IIs were introgressed from indica to japonica, which was contradictory to the reported 55 major domestication sweeps introgressed from japonica to indica [10], suggesting that not only introgression from japonica to indica, but also from indica to japonica could be detected in our rice cultivars.

Functional classification and selection pressure of specific genes

In the DR-I and DR-II regions, 163 and 110 genes were detected, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S7 and S8). To determine the functional categories of these genes, we summarized the possible functions of these genes using rice Gene Ontology (GO) annotation (http://geneontology.org/) (Figure S4).

Most of the genes in the DR-I regions have a significant functional enrichment in cell growth, anatomical structure morphogenesis, cellular component organization, DNA metabolic process, reproduction, embryo development, and photosynthesis (Additional file 1: Figure S4); for example, some functions responding to seed or coleoptile development (Os01g61380, Os03g05820, Os03g06010-Os03g06060, Os03g06120, Os03g06360, Os03g06890, and Os05g41030), flower, pollen, or anther development (Os03g05140, Os05g38990, Os07g08170, and Os10g39880), root development (Os03g43400 and Os03g43410) (Additional file 1: Table S7). This functional enrichment analysis was consistent with the findings of previous reports that the differentiation of morphological and physiological traits was an adaptation to distinct climatic, ecogeographic, and cultural conditions between indica and japonica [28–30].

Because the selective sweep was respectively detected in indica and japonica, and significant differentiation between these two subspecies was observed, we expected that more genes under positive selection would be detected in the genes of DR-I during the differentiation of indica and japonica. Therefore, the Ka/Ks between indica and japonica samples was employed to evaluate positive selection of these genes. Interestingly, 43 out of the 163 genes (25.9%) with Ka/Ks >1 (or Ks = 0, Ka > 0) were detected (Additional file 1: Table S7), which showed a significantly higher proportion (χ 2 with Yates correction = 32.4, d.f. = 1, P < 0.0001) than that (2,678 out of 27,384, ~8.7%) of the genome-wide reports [7], suggesting that a large number of the DR-I genes were under positive selection during the differentiation of indica and japonica, and the differentiation of the two subspecies was driven by both artificial and natural selection with strong positive selection, which directly acted on many characteristics.

Genes in the DR-II regions were enriched in cell differentiation, anatomical structure morphogenesis, cell growth, photosynthesis, awns development, flower development, cell cycle, embryo development, and reproduction (Additional file 1: Figure S5 and Table S8). This functional enrichment was consistent with the reports on the differentiation of morphological and physiological traits for cultivars and wild rice. For example, sh4 19, a gene related to shattering, which was included in the selective sweep regions in the research of Huang et al. [10], was also found in our DR-II. Remarkably, a more recent research reported a highly conserved region in chromosome 4, which was also included in our DR-II regions [26]. LABA1 (LOC_Os04g43840) and GAD1 (LOC_Os08g37890) were also detected in our results, which were associated with long, barbed awns in wild rice (Table S8) [31, 32].

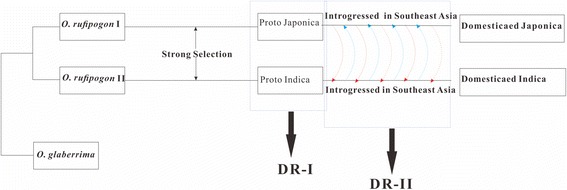

Discussion

There is currently an ongoing debate both in the genetic and archaeological arenas on the origins of Asian cultivated rice [27]. Numerous studies have suggested that indica and japonica may have multiple origins and that the two subspecies might have been independently domesticated from different isolates of the wild rice of O. rufipogon [8, 27], and indica might have originated in eastern India and japonica from southern China [8]. However, a recent report has shown that a single origin for domesticated Asia rice was more likely to have occurred than multiple origins, as indicated by the results of Bayesian phylogenetic analyses [9]. Interestingly, a more recent study based on genome-wide variation has reported that japonica might have been first domesticated from wild rice of Or-III in southern China, and was subsequently followed by dispersal to Southeast Asia, and then crossed with local wild rice of Or-I to generate indica after several cross-differentiation-selection cycles [10]. Another model was recently proposed by Choi et al., in support of separate origins for different rice subspecies, but only a single de novo domestication of rice which occurred in japonica. [33]. Other studies have shown that the domestication process of rice might have been initiated multiple times, followed by extensive introgression of strongly selected alleles, e.g., some important domesticated genes of sh4, rc, and waxy, which originated in japonica and spread to indica [19, 34, 35]. Therefore, frequent introgression between indica and japonica is a widely accepted theory for the domestication of rice [27]. However, the geographical discordance relating to the concept that japonica was domesticated in Southern China, and indica was generated in Southeast Asia or South Asia by japonica crossing with local wild rice after its dispersal remains elusive.

Interestingly, our data have shown that japonica and indica may have a common place of the origin in Indo-China Peninsula in the DR-I and DR-II, which have the highest identity to that of the wild rice from Indo-China Peninsula and South Asia, suggesting that all these regions with strongly selective sweep may have a common place with the highest identity for some accessions of the wild rice. This result was consistent with those of a recently published study [26]. On the other hand, our data also showed that the average diversity in the DR-II regions either within japonica, indica, or both was significantly lower than that in the DR-I blocks within japonica (t-test, P = 0.011) or indica (t-test, P < 0.0001) (Tables 2 and 3), suggesting that the DR-I blocks were independently fixed in indica or japonica prior to the fixation of these DR-II blocks. Third, our data also showed that all of the 28 DR-IIs were introgressed from indica to japonica, which was inconsistent with the findings of previous reports in that 55 major domestication sweeps might have introgressed from japonica to indica [10], suggesting that not only introgression from japonica to indica but also from indica to japonica can be detected in the rice cultivars.

Therefore, a possible model of the origin of the cultivated rice (Fig. 3) may be that (i) the proto-indica and proto-japonica might have independently originated from the divergent wild rice in the Indo-China Peninsula, in which the DR-Is with significant divergence between the two subspecies may have been domesticated during this period; (ii) then, followed by frequent introgression from indica into proto-japonica also in the Indo-China Peninsula (detected in this study), or from japonica into proto-indica in southern China [10, 27], modern japonica and indica formed and spread to different regions. During this period, DR-IIs may have been domesticated in all these cultivated rice (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The model of the origin of the cultivar rice japonica and indica. In this model, the modern japonica and indica were domesticated from different wild rice

Fig. 4.

Origin place of the wild rice selected as the Japonica-clade (red dots) and Indica-clade (blue dots) by DR-I. As shown in this figure, the two clades overlapped in Southeast Asia. A geographical map was created using maps packages [51] (version 3.0) from CRAN (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/maps/index.html)

Rice have undergone a series of similar phenotypic domestication for effective harvest and planting from their wild progenitors, including a reduction in seed shattering and dormancy, synchronization of seed maturation, increase in seed sizes, and decrease in culm number and branches [11, 19, 36–40]. On the other hand, the two major rice subspecies are differentiated by a number of morphological and physiological characters, along with a substantial sterility barrier [41]. Therefore, we expected that the genes with strongly selective sweep should have functional bias.

Interestingly, for the genes found in DR-I regions, on one hand, a significant functional bias was detected in seed or coleoptile development, flower, pollen or anther development, and root development (Additional file 1: Table S7), which was consistent with the differentiation of the morphological and physiological traits, e.g., seed size, between the two subspecies. On the other hand, a large number of these domesticated genes were detected to have undergone positive selection, suggesting that the differentiation of the two subspecies was driven by both natural and artificial selection with strong positive selection in these domesticated genes.

Furthermore, some genes under strong positive selection had a tendency of being clustered within small regions. For instance, a 0.6-Mb block containing 2 DR-Is showed a significantly lower diversity in japonica than indica, which strongly implied selection sweep and genetic bottleneck (Additional file 1: Figure S6). Within this block, 8 genes (Os03g05820, Os03g06010–Os03g06060, and Os03g06120), which may be related to root development and coleoptile development, were clustered [29–31]. In addition, not only these 8 genes, but also the nearby genes were under a significantly positive selection (Additional file 1: Table S7), although the function of the other genes was unclear or apparently showed no relationship with the differentiation of japonica and indica. Hitchhiking effect may explain such a high positive selection of this region, or that the genes with unknown functions may have played major roles in the differentiation of the two rice subspecies. Similar results were observed in DR-II (Additional file 1: Figure S7 and Table S8), suggesting that these regions may contain a large number of important genes that were related to the domestication of the cultivated rice. Coincidentally, two clustered regions in chr04: 26.0 Mb–27.1 Mb and chr08:23.7 Mb-24.9 Mb were also detected by Hua et al. [31] and Jin et al. [32]. Thus, the present research not only determined the origin of the Asian rice cultivars in higher detail, but also facilitated in the discovery of more genes relative to domestication and breeding. Our method could be applied to molecular breeding and agricultural schemes of various rice cultivars.

We need to notice that, although the samples were only selected according to the coverage threshold, we could not totally rule out sampling bias. In this study, we only focused on those most highly-differentiated indica and japonica accessions, this could be failed to reflect the truly diversity between indica and japonica. The somewhat controversial conclusions from different researches [10, 33] might in turn reflect the importance of sampling strategy. However, as we are not going to draw a final conclusion on the debate of rice domestication, we called for more extensive samplings to further test the generalizability of our conclusions.

Conclusion

By using 296 whole-genome sequenced rice cultivars in 3000 rice project and 39 diverse wild rice of O. rufipogon, our research had detected 28 DR-Is and 28 DR-IIs, which covered 890 kb and 640 kb regions, and harbored 163 and 110 genes, respectively. The results suggested that both DR-Is and DR-IIs might have originated from the Indo-China Peninsula to southern China. In addition, functional bias with significant positive selection has been detected in the genes of DR-I, suggesting that the selective sweep with significant positive selection might drive for the differentiation of the japonica and indica rice subspecies.

Methods

Data source

The resequencing data of japonica and indica individuals was obtained from the 3,000 rice project 21 (Additional file 1: Table S1). For wild rice (O. rufipogon), 371 rice samples were obtained from Huang et al. [10], 10 were obtained from Xu et al. [25], one was obtained from Ohyanagi et al. [42] and one was obtained from Zhang et al. [43] (Additional file 1: Table S3). The resequencing data of 20 African domesticated rice (O. glaberrima) were collected from Wang et al. [44] (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Analysis of sequencing data

All available indica and japonica individuals were selected for further analysis based on the sequencing depth (japonica ≥15× and indica ≥20×). All reads were mapped against the reference genome Nipponbare (IRGSP1.0, http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) using BWA-mem (version 0.7.9a-r786) [45] with option “-M”. Picard-MarkDuplicates (version 1.114, http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) and GATK-IndelRealigner (version 3.2) [46] were applied to correct mapping results. GATK-UnifiedGenotyper was applied to identify SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphism) of each rice individual. To reduce possible sequencing and mapping errors, SNPs with poor quality (quality <50), low depth (depth < 3) or low frequency (MAF < 5%) were excluded. These retained SNPs were then used for further analysis.

Selection of japonica and indica samples

Nucleotide diversity (π) or divergence (Dxy), which was defined as the ratio between SNP numbers and the corresponding region length [47], served as criterion for the selection of indica and japonica individuals. For example, as to one japonica individual, we defined π1 as the average π value between this individual and all the other japonica samples. Similarly, Dxy 1 was the average Dxy value between this japonica individual and all the indica samples. When π1 ≥ Dxy 1, this japonica individual was considered to be a non-typical japonica rice and excluded from the analysis. Finally, principal components analysis (PCA) was also performed with VCFtools (http://vcftools.sourceforge.net/) and GCTA (http://cnsgenomics.com/software/gcta/), using all the SNPs in the whole genome. The first two components of the PCA analysis were adapted to further remove the japonica/indica individuals that were not clustered.

Detection of the differentiated/domesticated regions

All the genomes were divided into 37,332 10-kb-windows and π/Dxy was applied as the genetic parameter to identify domesticated regions. For each window, when the π values within japonica or indica individuals were both ≤0.0002, but the Dxy between japonica and indica was ≥0.002, we defined this region of this window as part of the domesticated region type I (DR-I). When the cultivar individuals had a low diversity (π values within the japonica and indica individuals were both ≤0.0002, and Dxy between japonica and indica was also ≤0.0002), whereas the π within the wild individuals was ≥0.001, we selected this window as part of domesticated region type II (DR-II). Furthermore, using IGV [48], regions with low mapping depth, or low mapping quality, or obvious translocation, or high proportion of repeat sequence, were discarded. In addition, adjacent uniform-type domesticated regions were merged into one block, even when the π value of a part of the block might be a bit higher than 0.0002. Finally, these blocks were used for further analysis as completed domesticated regions (DR-I or DR- II).

Calculation of the genetic parameters

For all the SNPs within the entire genome of selected japonica and indica individuals, when most (≥80%) japonica individuals shared one genotype whereas most (≥80%) indica individuals shared another genotype, we defined this SNP site as a near-fixed marker between japonica and indica. Then, using these near-fixed markers, non-synonymous (Ka) or synonymous (Ks) substitutions of the coding sequences between japonica and indica were calculated using the Nei-Gojobori method with Jukes-Cantor correction. Whole-genome Fst values and Tajima’s D indices were calculated by VCFtools. Calculation of the Fst and its significance in domesticated regions were performed by Arlequin31 [49]. A 5% confidence interval within the whole rice genome was used to identify significance of Tajima’s D.

SNPs in DR-I or DR-II were used to build corresponding neighbor-joining (NJ) trees with Jukes-Cantor model using MEGA v5.0 [50]. Bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates was used to estimate the stability of internal nodes and gaps/missing data treatment was performed to identify pairwise deletions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31601041, 31570368), Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT_14R27), the National Major Special Project on New Varieties Cultivation for Transgenic Organisms (No. 2016ZX08009001-003), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production, China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016 M601772).

Availability of data and materials

All the sequencing data were downloaded from NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession PRJEB6180, ERP001143, ERP000729, ERP000106, PRJNA13765, DRA000438, SRA023116 and SRP051089 (see Additional file 1: Table S1, Table S3 and Table S4 for reference detail). The phylogenetic data has been deposited in the website (http://gattaca.nju.edu.cn/pub_data.html).

Authors’ contributions

D.T., S.Y. and L.W. designed the study. Y.Y., Q.Z., S.Z., L.G., W.S. and X.Z. performed research; Y.Y., Q. Z., S.Z., L.G. and L.W. analyzed data; S.Y. and L.W. composed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- DR-I

Domesticated regions of type I

- DR-II

Domesticated regions of type II

- GO

Gene Ontology

- PCA

Principle component analysis

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

Additional file

PCA plots of the first two components before (a) and after (b) sample selection. Figure S2. The proportions of the genome-wide diversity within the groups of japonica, indica and wild rice and divergence between japonica and indica group. Figure S3. Diversity/divergence relationship between rice groups. Figure S4. GO statistic of the DR-I regions. Figure S5. GO statistic of the DR-II regions. Figure S6. Clustered regions of DR-I. Figure S7. Clustered regions of DR-II. Table S1. List of 330 rice cultivars downloaded from the 3 K-rice project. Table S2. PCA value for each sample. Table S3. List of African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) and wild rice (O. rufipogon and O. nivara) used to generate phylogenetic tree. Table S4. List of wild rice obtained from Huang et al. used in this project. Table S5. SNP genotype of DR-I. Table S6. SNP genotype of DR-II. Table S7. List of 163 genes in the 28 DR-I regions. Table S8. List of 110 genes in the 28 DR-II regions. (PDF 2465 kb)

Contributor Information

Sihai Yang, Phone: +86-25-89686406, Email: sihaiyang@nju.edu.cn.

Long Wang, Phone: +86-25-89686406, Email: wanglong@nju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gao Z-Y, Zhao S-C, He W-M, Guo L-B, Peng Y-L, Wang J-J, et al. Dissecting yield-associated loci in super hybrid rice by resequencing recombinant inbred lines and improving parental genome sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:14492–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306579110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y, Zhu K, Xia H, Chen L, Chen K. Comparative proteomic analysis of indica and japonica rice varieties. Genet Mol Biol. 2014;37:652–61. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572014005000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oka HI. Origin of Cultivated Rice. Elsevier. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oka H. Experimental studies on the origin of cultivated rice. Genetics. 1974;78:475–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/78.1.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang P, Molina J, Flowers JM, Rubinstein S, Jackson SA, Purugganan MD, et al. Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon: a genome-wide view. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:4593–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang T-T. The origin, evolution, cultivation, dissemination, and diversification of Asian and African rices. Euphytica. 1976;25:425–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00041576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun X, Jia Q, Guo Y, Zheng X, Liang K. Whole-genome analysis revealed the positively selected genes during the differentiation of indica and temperate japonica rice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Londo JP, Chiang Y-C, Hung K-H, Chiang T-Y, Schaal BA. Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestications of cultivated rice. Oryza sativa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9578–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603152103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molina J, Sikora M, Garud N, Flowers JM, Rubinstein S, Reynolds A, et al. Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8351–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104686108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Kurata N, Wei X, Wang Z-X, Wang A, Zhao Q, et al. A map of rice genome variation reveals the origin of cultivated rice. Nature. 2012;490:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature11532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li C, Zhou A, Sang T. Genetic analysis of rice domestication syndrome with the wild annual species. Oryza nivara. New Phytol. 2006;170:185–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Si W, Yuan Y, Huang J, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Widely distributed hot and cold spots in meiotic recombination as shown by the sequencing of rice F2 plants. New Phytol. 2015;206(4):1491–502. doi: 10.1111/nph.13319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang S, Wang L, Huang J, Zhang X, Yuan Y, Chen J-Q, et al. Parent-progeny sequencing indicates higher mutation rates in heterozygotes. Nature. 2015;523:463–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu K, Xu X, Fukao T, Canlas P, Maghirang-Rodriguez R, Heuer S, et al. Sub1A is an ethylene-response-factor-like gene that confers submergence tolerance to rice. Nature. 2006;442:705–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanagihara S, McCouch SR, Ishikawa K, Ogi Y, Maruyama K, Ikehashi H. Molecular analysis of the inheritance of the S-5 locus, conferring wide compatibility in Indica/Japonica hybrids of rice (O. sativa L.). TAG Theor. Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 1995;90:182–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu B, Wang W, Ou S, Tang J, Li H, Che R, et al. Variation in NRT1.1B contributes to nitrate-use divergence between rice subspecies. Nat Genet. 2015;47:834–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu B-F, Si L, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Zhu J, Shangguan Y, et al. Genetic control of a transition from black to straw-white seed hull in rice domestication. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1301–11. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.168500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan L, Li X, Liu F, Sun X, Li C, Zhu Z, et al. Control of a key transition from prostrate to erect growth in rice domestication. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1360–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, Zhou A, Sang T. Rice domestication by reducing shattering. Science. 2006;311:1936–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1123604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abe A, Kosugi S, Yoshida K, Natsume S, Takagi H, Kanzaki H, et al. Genome sequencing reveals agronomically important loci in rice using MutMap. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:174–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The 3,000 rice genomes project. GigaScience. The 3,000 rice genomes project. 2014;3:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Huang X, Wei X, Sang T, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Zhao Y, et al. Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat Genet. 2010;42:961–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J, Tang T, Tang H, Huang J, Shi S, Wu C-I. The accumulation of deleterious mutations in rice genomes: a hypothesis on the cost of domestication. Trends Genet TIG. 2006;22:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang C, Kawahara Y, Mizuno H, Wu J, Matsumoto T, Itoh T. Independent domestication of Asian rice followed by gene flow from japonica to indica. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1471–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X, Liu X, Ge S, Jensen JD, Hu FY, Li X, et al. Resequencing 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice yields markers for identifying agronomically important genes. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:105–U157. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Civáň P, Craig H, Cox CJ, Brown TA. Three geographically separate domestications of Asian rice. Nat Plants. 2015;1:15164. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross BL, Zhao Z. Archaeological and genetic insights into the origins of domesticated rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6190–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308942110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magneschi L, Kudahettige RL, Alpi A, Perata P. Expansin gene expression and anoxic coleoptile elongation in rice cultivars. J Plant Physiol. 2009;166:1576–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitagawa K, Kurinami S, Oki K, Abe Y, Ando T, Kono I, et al. A novel kinesin 13 protein regulating rice seed length. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1315–29. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song W-Y, Hörtensteiner S, Tomioka R, Lee Y, Martinoia E. Common functions or only phylogenetically related? The large family of PLAC8 motif-containing/PCR genes. Mol Cells. 2011;31:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0024-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hua L, Wang DR, Tan L, Fu Y, Liu F, Xiao L, et al. LABA1, a Domestication Gene Associated with Long, Barbed Awns in Wild Rice. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1875–88. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin J, Hua L, Zhu Z, Tan L, Zhao X, Zhang W, et al. GAD1 Encodes a Secreted Peptide That Regulates Grain Number, Grain Length, and Awn Development in Rice Domestication. Plant Cell. 2016;28:2453–63. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi JY, Platts AE, Fuller DQ, Hsing Y-I, Wing RA, Purugganan MD. The rice paradox: Multiple origins but single domestication in Asian rice. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(4):969–79. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konishi S, Izawa T, Lin SY, Ebana K, Fukuta Y, Sasaki T, et al. An SNP caused loss of seed shattering during rice domestication. Science. 2006;312:1392–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1126410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweeney MT, Thomson MJ, Cho YG, Park YJ, Williamson SH, Bustamante CD, et al. Global dissemination of a single mutation conferring white pericarp in rice. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nunes AL, Delatorre CA, Merotto A. Gene expression related to seed shattering and the cell wall in cultivated and weedy rice. Plant Biol Stuttg Ger. 2014;16:888–96. doi: 10.1111/plb.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oba S, Sumi N, Fujimoto F, Yasue T. Association between Grain Shattering Habit and Formation of Abscission Layer Controlled by Grain Shattering gene sh-2 in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Jpn J Crop Sci. 1995;64:607–15. doi: 10.1626/jcs.64.607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan S, Zou G, Li S, Wang H, Liu H, Zhai G, et al. Seed size is determined by the combinations of the genes controlling different seed characteristics in rice. TAG Theor. Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 2011;123:1173–81. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1657-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang H, et al. Genetic Analysis and Gene-Mapping of Two Reduced-Culm-Number Mutants in Rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2006;48:341–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2006.00224.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujita D, Ebron LA, Araki E, Kato H, Khush GS, Sheehy JE, et al. Fine mapping of a gene for low-tiller number, Ltn, in japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.) variety Aikawa 1. TAG Theor. Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 2010;120:1233–40. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Zhao X, Cheng K, Du H, Ouyang Y, Chen J, et al. A killer-protector system regulates both hybrid sterility and segregation distortion in rice. Science. 2012;337:1336–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1223702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohyanagi H, Ebata T, Huang X, Gong H, Fujita M, Mochizuki T, et al. OryzaGenome: Genome Diversity Database of Wild Oryza Species. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:e1. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Q-J, Zhu T, Xia E-H, Shi C, Liu Y-L, Zhang Y, et al. Rapid diversification of five Oryza AA genomes associated with rice adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:E4954–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418307111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang M, Yu Y, Haberer G, Marri PR, Fan C, Goicoechea JL, et al. The genome sequence of African rice (Oryza glaberrima) and evidence for independent domestication. Nat Genet. 2014;46:982–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinforma Ed Board Andreas Baxevanis Al. 2013;43:11.10.1–33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nei M, Li WH. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:5269–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–92. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:564–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becker RA, Wilks AR. Maps in S. AT&T Bell Laboratories Statistics Research Report. 1993. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the sequencing data were downloaded from NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession PRJEB6180, ERP001143, ERP000729, ERP000106, PRJNA13765, DRA000438, SRA023116 and SRP051089 (see Additional file 1: Table S1, Table S3 and Table S4 for reference detail). The phylogenetic data has been deposited in the website (http://gattaca.nju.edu.cn/pub_data.html).