Abstract

The importance of brain inflammation to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis has been accepted of late, with it currently being held that brain inflammation aggravates AD pathology. One important aspect of brain inflammation is the recruitment and activation of microglia, a process termed microgliosis. Kinins and bradykinin (BK), in particular, are major pro-inflammatory mediators in the periphery, although all of the factors comprising the kinin system have also been described in the brain. Moreover, it was shown that the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide (a component of AD plaques) enhances kinin secretion and activates BK receptors that can, in turn, stimulate Aβ production. Still, the role of bradykinin in modulating brain inflammation and AD is not completely understood. In this study, we aimed to investigate the roles of the bradykinin B1 receptor (B1R) and bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R) in regulating microglial secretion of pro-inflammatory factors in vitro. Furthermore, the effects of intranasal administration of specific B1R and B2R antagonists on Aβ burden and microglial accumulation in the brains of transgenic AD mice were studied. The data obtained show that neither R-715 (a B1R antagonist) nor HOE 140 (a B2R antagonist) altered microglial cell viability. However, R-715, but not HOE 140, markedly increased lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide (NO) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) release, as well as inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in BV2 microglial cells. Neither antagonist altered NO nor TNF-α production in non-stimulated cells. We also showed that intranasal administration of R-715 but not HOE 140 to 8-week-old 5X familial AD mice enhanced amyloid burden and microglia/macrophage accumulation in the cortex. To conclude, we provide evidence supporting a role of B1R in brain inflammation and in the regulation of amyloid deposition in AD mice, possibly with microglial/macrophage involvement. Further studies are required to test whether modulation of this receptor can serve as a novel therapeutic strategy for AD.

Keywords: bradykinin, brain inflammation, HOE 140, microglia, R-715

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a prevalent neurodegenerative disease (1) that is characterized by two neuropathological hallmarks, namely the deposition of amyloid β plaques and the accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles (2, 3). The role that brain inflammation plays in AD pathogenesis has only recently been appreciated. Currently, brain inflammation is thought to contribute to and to exacerbate AD pathology (4, 5). One important aspect of the central immune response to brain inflammation is microglial activation.

Microglia are the resident phagocytes of the brain. These cells use their processes to scan the brain for pathogens and debris (6). Microglia also maintain brain plasticity and remodel synapses (7, 8). In AD, microglia bind soluble amyloid β (Aβ) oligomers and fibrils and become activated. The activated microglia then start to engulf Aβ fibrils by phagocytosis. Inefficient phagocytosis of Aβ has been identified as a major pathogenic pathway (5). Microglia are likely to exist in a range of phenotypic states during chronic inflammation in AD. Upon binding to Aβ, microglia release pro-inflammatory molecules, such as interleukin-1 β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IL-12, as well as reactive oxygen species, like nitric oxide (NO) (9–11). In turn, pro-inflammatory conditions promote neuronal damage mediated by Aβ and decrease the phagocytosis of these oligomers and their degradation by microglia (12, 13).

Although much is known of the molecular basis of initiating signals and pro-inflammatory chemical mediators in brain inflammation, it has only recently become apparent that endogenous stop signals are critical players at early checkpoints during the various stages of brain inflammation. Some neuropeptides that are produced during the ongoing inflammatory response have emerged as endogenous anti-inflammatory agents that participate in the regulation of processes that ensure self-tolerance and/or inflammation resolution. Neuropeptides, such as kinins, can regulate brain inflammation and affect microglial functions both in vitro and in vivo (14, 15). Thus, the release of these factors can determine whether microglia assume a neuroprotective phenotype.

Kinins, in particular bradykinin (BK), are pro-inflammatory mediators in the periphery. At peripheral sites, BK can elicit all of the major signs of inflammation, namely pain, hyper-perfusion, and increased vascular permeability (16–19). All kinin system components have also been described in the central nervous system (20). Indeed, high BK levels are found after brain trauma and ischemia (21). Furthermore, it was shown that Aβ upregulates BK receptors and kinin release, followed by BK-induced Aβ synthesis (22). Still, the role that bradykinin plays in AD modulation is not completely understood. BK activates two types of receptors, namely, the B1 receptor [bradykinin B1 receptor (B1R)] and the B2 receptor [bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R)] (23, 24). B2R is a constitutive receptor and has high affinity for BK, while B1R is generally upregulated following tissue injury and binds with high affinity to des-Arg9-BK, a kinin metabolite (24). In the brain, microglial cells express both receptors (14, 25).

In the present study, our intent was to investigate the contributions of B1R and B2R in mediating microglial inflammation in vitro. Moreover, the in vivo influence of intranasal administration of specific B1R and B2R antagonists on Aβ burden and microglial accumulation in brains of transgenic AD mice was considered.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures

The BV2 microglial cell line (provided by Prof. Rosario Donato, Department of Experimental Medicine and Biochemical Sciences, University of Perugia) was seeded in 6-well, 24-well, or 96-well plates at densities of 1 × 106, 3 × 105, and 2 × 104 cells per well, respectively. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 0.4 mM l-glutamine. To create a sterile environment, 100 U/ml of penicillin and 100 µg/ml of streptomycin were added. Cells were grown in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. At the beginning of each experiment, the cells were incubated with serum-free medium (SFM) for 4 h, followed by a 22-h incubation with the indicated test agents in SFM supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). BV2 cells were treated with R-715, a B1R selective antagonist, and HOE 140, a B2R selective antagonist, both purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai, China), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5 was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell Count

At the end of each experiment, cells were harvested after incubation with 1 ml SFM for 1 h at 4°C and counted using a Z1 Coulter counter (Coulter Electronics, Miami, FL, USA).

Cell Viability

Cell viability was determined by a Cell Proliferation Kit (XTT) (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay was performed using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad model 680).

Determination of NO Levels (Griess Reaction)

Nitrite levels were determined in the culture supernatants using the Griess reaction. Nitrite standard curve samples or supernatants (100 µl each) were mixed with 100 µl Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) in 96-well plates. Thereafter, the plates were incubated for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. Nitrite levels were measured with a microplate reader at 540 nm.

Determination of TNF-α Levels (ELISA)

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

SDS Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blot Analysis

The expression levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) protein in BV2 microglial cells were analyzed by Western blot (26). Briefly, cells were harvested using lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, and 1% deoxycholic acid) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells lysates were incubated at 4°C for 30 min, followed by a 15 min centrifugation (12,000 g) at 4°C. Thereafter, protein levels were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Aliquots of whole cell lysates containing 40 µg protein were denatured and separated on 7.5% polya-crylamide-SDS gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Non-specific sites were blocked by 4% BSA (90 min incubation at room temperature). This was followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with rabbit anti-iNOS antibodies (1:500; Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). After washing, the membranes were incubated with IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies (1:5,000; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 90 min at room temperature. Finally, enhanced chemiluminescence solution was added, and the membranes were exposed to X-ray film (Fuji medical X-ray film, FujiFilm). Protein levels were normalized to β-actin levels using mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibodies (1:25,000; MP Biological, Santa Ana, CA, USA) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (1:20,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). A computerized image analysis system (EZ Quant-Gel 2.2, EZQuant Biology Software Solutions, Israel) was used for semi-quantitative analysis.

Mice

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Israel (Jerusalem, Israel). Transgenic 5X familial AD (5XFAD) mice were provided by Prof. Robert Vassar (Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Northwestern University). 5XFAD mice include five mutations under the transcriptional control of the neuron-specific mouse Thy-1 promoter, with three mutations in the human APP695 gene (Swedish K670N, M671L, Florida I716V and London V717I) and two mutations in the human presenilin-1 gene (M146L, L286V). At the age of 2 months, 5XFAD mice evolve Aβ accumulation and gliosis (27). The human APP gene was detected by PCR analysis of mice tail tissue DNA. Mice were placed in cages at temperatures of 22 ± 2°C and 65% humidity. Food and water supply was made available, and a 12 h light/dark cycle was maintained. All animal studies were performed according to the recommendations of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The protocol employed was approved by this committee (approval number IL-30-08-2011).

In the first experiment, 8-week-old mice were divided into three groups, namely WT mice treated with R-715, 5XFAD mice treated with saline, and 5XFAD mice treated with R-715. In the second experiment, mice were again divided into three groups, namely WT mice treated with HOE 140, 5XFAD mice treated with saline, and 5XFAD mice treated with HOE 140. The mice received daily intranasal treatment of 1 mg/kg per day for 18 days (5 days/week).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized upon intra-peritoneal injection of 0.2 ml ketamine–xylazine mixer (1:1). Brains were removed following cold PBS cardiac perfusion and were divided into two hemispheres. One hemisphere from each mouse brain was incubated overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 4°C, followed by incubation in 30% sucrose solution at 4°C for 2 days. The hemispheres were then frozen in molds containing tissue adhesive (O.C.T. compound, Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA, USA) at −80°C. All hemispheres were cut into sagittal sections (40 µm) using a cryostat and maintained at −20°C in PBS:ethyleneglycol:glycerol (2:1:1) non-freezing solution. Free-floating sections were washed using 0.05% PBS/Tween 20 and permeabilized using 0.5% PBS/Triton X-100. After blocking non-specific binding using antibody diluent solution (GBI Labs, Mukilteo, WA, USA), sections were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with rabbit anti-human Aβ (1:250; a gift from Prof. Alon Monsonego, The Shraga Segal Department of Microbiology and immunology, Faculty of Health Sciences and the National institute of Biotechnology in the Negev, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev) and rat anti-mouse/human CD11b antibodies (1:25, Biolegend). Primary antibodies were diluted in antibody diluent solution. Thereafter, the sections were rinsed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the appropriate secondary antibody, i.e., Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000) or Alexa fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (1:250), both from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Secondary antibodies were diluted in 0.05% PBS/Tween 20. After washes, the sections were mounted with mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector labs) on charged slides and stored at 4°C. An Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) at 1,024 × 1,024 pixel resolution with a ×10 objective was used for imaging. In each experiment, five sections from the cortex of each animal were analyzed. Aβ and CD11b staining was quantified using the ImageJ software version 1.40C (NIH). Average fluorescent Aβ- and CD11b-containing areas were calculated for each treated group.

Statistical Analysis

For each experiment, results are presented as the mean ± SEM. To assess the statistical significance of differences between treatment groups, one-way analysis of variance was performed, followed by a post hoc multiple comparison test (Tukey–Kramer Multiple Comparison Test). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

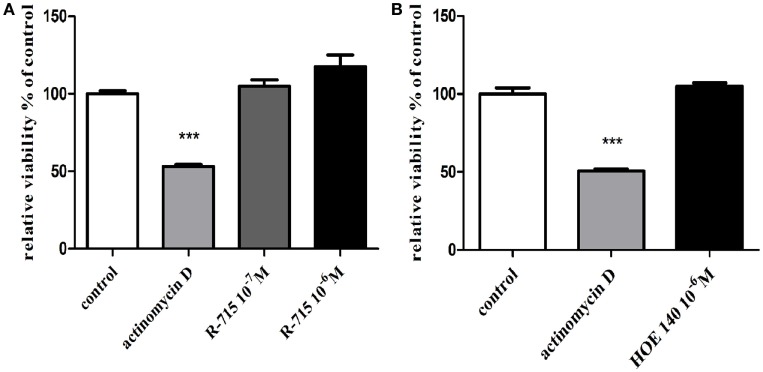

Serving as a positive control, actinomycin D, significantly reduced BV2 microglial cell viability (Figure 1). By contrast, neither the B1R antagonist R-715 at concentrations of 10−7 and 10−6 M (Figure 1A) nor the B2R antagonist HOE 140 at a concentration of 10−6 M (Figure 1B) altered microglial cell viability, as measured with XTT assay.

Figure 1.

Effects of bradykinin B1 receptor (B1R) and bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R) antagonists on the viability of BV2 cells. Cells were incubated with (A) the B1R antagonist R-715 (10−7 and 10−6 M) or (B) the B2R antagonist HOE 140 (10−6 M) for 24 h. At the end of the experiment, viability was assessed by the XTT assay. Results are given as mean ± SEM, n = 4; a one-way analysis of variance and Tukey–Kramer Multiple Comparison Test were performed to determine statistical significance; ***P < 0.001 versus the control.

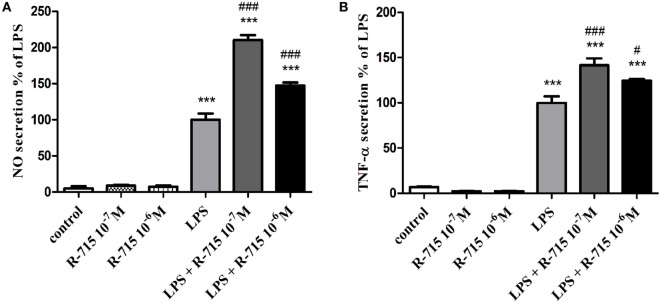

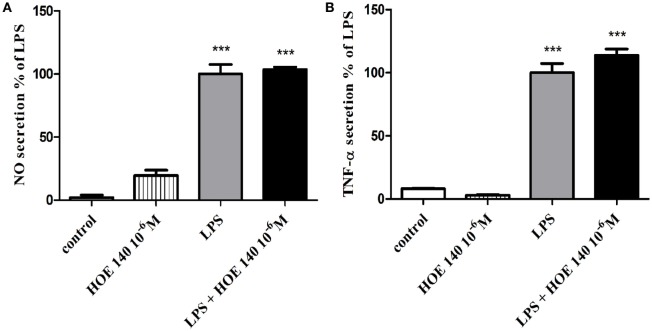

The production of NO (Figure 2A) and TNF-α (Figure 2B) in non-stimulated BV2 cells or in BV2 cells induced by LPS (7 ng/ml) and treated with R-715 (10−7 and 10−6 M) was next considered. LPS markedly enhanced NO and TNF-α production, as compared with controls. R-715 at concentrations of 10−7 and 10−6 M significantly increased LPS-induced NO secretion (Figure 2A). R-715, at concentrations of 10−7 and 10−6 M, also increased LPS-induced TNF-α secretion (Figure 2B). By contrast, R-715 did not alter NO (Figure 2A) or TNF-α (Figure 2B) production in non-stimulated cells. However, the selective B2R antagonist HOE 140 failed to alter NO (Figure 3A) or TNF-α (Figure 3B) release from either non-stimulated or LPS-stimulated cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of the bradykinin B1 receptor (B1R) antagonist on basal and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced NO and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) release from BV2 cells. Cells were incubated with the B1R antagonist R-715 (10−7 and 10−6 M) in the presence or absence of LPS (7 ng/ml) for 24 h. NO (A) and TNF-α (B) levels were measured in the media, and the cells were counted. Results are representatives of three independent experiments and are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3–6; statistical significance was assessed by one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey–Kramer Multiple Comparison Test; ***P < 0.001 versus the control, ###P < 0.001 versus LPS, and #P < 0.05 versus LPS.

Figure 3.

Effect of the bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R) antagonist on basal and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced NO and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) release from BV2 cells. Cells were incubated with the B2R antagonist HOE 140 (10−6 M) in the presence or absence of LPS (7 ng/ml) for 24 h. NO (A) and TNF-α (B) levels were measured in the media, and the cells were counted. Results are representatives of three independent experiments and are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3–6; statistical significance was assessed by one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey–Kramer Multiple Comparison Test; ***P < 0.001 versus control.

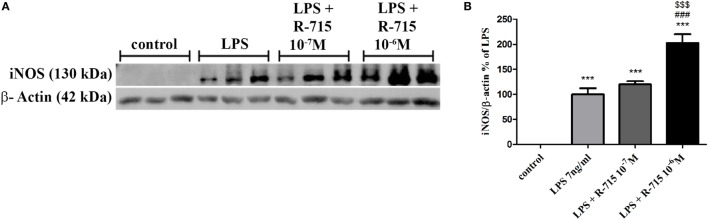

As shown in Figure 4, a 24-h treatment of BV2 cells with LPS (7 ng/ml) significantly increased iNOS expression levels. 10−6 M of R-715 increased the LPS-induced iNOS expression by up to 102%.

Figure 4.

Effect of the bradykinin B1 receptor (B1R) antagonist on iNOS expression in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated BV2 cells. Cells were incubated with the B1R antagonist R-715 (10−7 and 10−6 M) and LPS (7 ng/ml) for 24 h. Whole cell lysates (40 µg) were examined by Western blot analysis using anti-iNOS or β-actin antibodies. The results shown here represent three independent experiments (A). The graph represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments (B), n = 3. One-way analysis of variance and a Tukey–Kramer Test were used to determine statistical significance; ***P < 0.001 versus the control, ###P < 0.001 versus LPS, and $$$P < 0.001 versus LPS + R-715 (10−7 M).

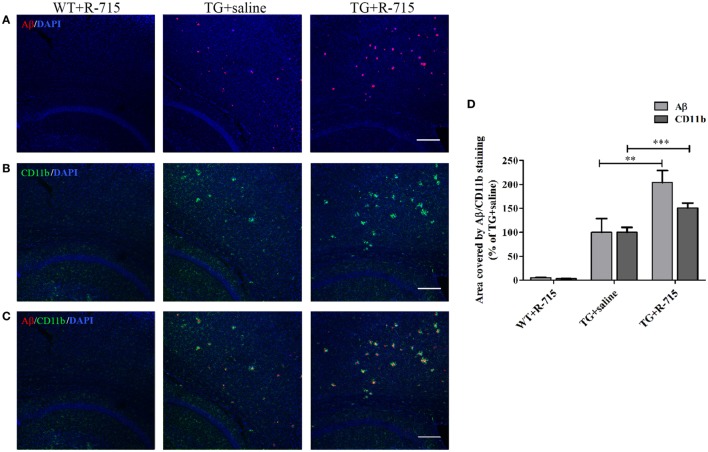

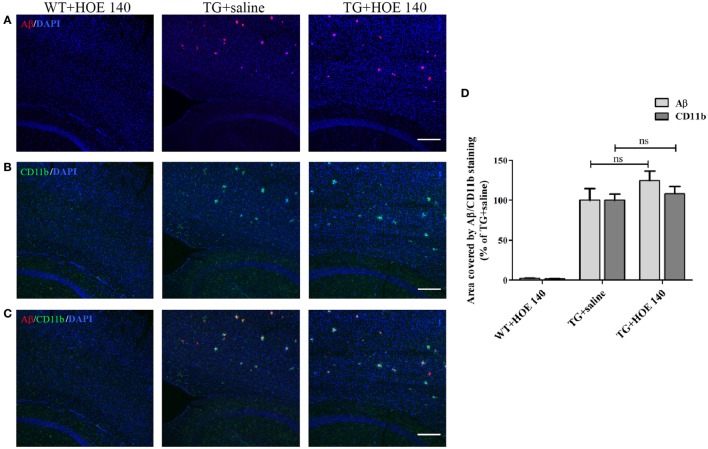

As anticipated, the cortex of WT mice intranasally administered with R-715 did not show any Aβ plaques (Figure 5A). Levels of both Aβ and CD11b (marker for microglial accumulation) were significantly enhanced in age-matched 5XFAD mice treated intranasally with the vehicle (Figure 5). However, as compared to 5XFAD mice treated with the vehicle, age-matched 5XFAD mice treated intranasally with R-715 (1 mg/kg/day) showed close to 100 and 50% increases in Aβ burden (Figures 5A,D) and CD11b staining (Figures 5B,D), respectively. 5XFAD mice intranasally treated with HOE 140 did not display any differences in plaque burden (Figures 6A,D) or CD11b staining (Figures 6B,D) in the cortex, as compared to vehicle-treated mice. Modified Figures 5 and 6 are adapted with permission from Asraf et al. (28).

Figure 5.

Effects of intranasal delivery of the bradykinin B1 receptor antagonist on amyloid burden and the accumulation of microglial cells in the cortex of 5X familial AD (5XFAD) mice. Two-month-old mice were treated with R-715 or the vehicle for 3½ weeks. After cardiac perfusion, their brains were cut into sections, stained for Aβ (red) (A) and CD11b (microglial accumulation) (green) (B) using appropriate antibodies and counter-stained with DAPI (blue). Representative confocal images of cortical sections from wild-type (WT) or 5XFAD mice (TG) are shown. (C) Merged images of Aβ and CD11b staining. The dose of intranasally administered R-715 was 1 mg/kg/day. Each group included 4–8 mice (n = 14–23 per experiment). The stained areas were quantified. The mean ± SEM of percentage of the stained areas is shown in the graphs, n ≥ 3 determinants (D). For statistical comparisons, a one-way analysis of variance and Tukey–Kramer Multiple Comparison Test were conducted. ***P < 0.001 versus TG + saline; **P < 0.01 versus TG + saline. The scale bar is 200 µm.

Figure 6.

The effects of intranasal delivery of the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist on amyloid burden and the accumulation of microglial cells in the cortex of 5X familial AD (5XFAD) mice. Two-month-old mice were treated with HOE 140 or the vehicle for 3½ weeks. After cardiac perfusion, their brains were cut into sections, stained for Aβ (red) (A) and CD11b (green) (B) using appropriate antibodies and counter-stained with DAPI (blue). Representative confocal images of cortical sections from wild-type (WT) or 5XFAD mice (TG) are shown. (C) Merged images of Aβ and CD11b staining. The dose of intranasally administered HOE 140 was 1 mg/kg/day. Each group included 4–7 mice (n = 15–19 per experiment). The stained areas were quantified. The mean ± SEM of percentage of the stained areas is shown in the graphs, n ≥ 3 determinants (D). For statistical comparisons, a one-way analysis of variance and Tukey–Kramer Multiple Comparison Test were conducted. ns, non-significant. The scale bar is 200 µm.

Discussion

Although BK is generally viewed as a central pro-inflammatory mediator (25, 29, 30), a possible protective role for BK in the brain has been proposed. Recently, we showed a dual effect of kinins on the production of prostaglandin (PG), a pro-inflammatory mediator, in cultured glial cells (i.e., microglia and astrocytes) (31). Specifically, the activation of B2 receptors increased PG synthesis, whereas B1R agonists inhibited synthesis of these pro-inflammatory mediators. We have, therefore, suggested that a regulatory loop exists in which B2 receptors mediate enhanced-glial inflammation. B1 receptors are subsequently upregulated and are involved in the attenuation of glial inflammation (31). These findings were confirmed in part by Noda et al., who documented reduced microglial inflammation upon BK treatment of LPS-induced cells (32, 33). More recently, we also showed that a B1 receptor agonist abrogated NO and TNF-α production in LPS-treated BV2 microglial cells (26).

In the present study, R-715 significantly enhanced iNOS expression and release of TNF-α and NO from BV2 microglia. Using immunocytochemistry, we previously demonstrated the expression of both B1 and B2 receptor sub-types in BV2 microglia (34). In the present study, B1Rs are blocked by R-715, and no regulatory feedback inhibition exists through B1 receptors. This suggests that endogenous BK, possibly released from BV2 cells, activates B2 receptors and contributes to the amplification of inflammation (TNF-α and NO synthesis) induced by LPS. Interestingly, BK and LPS were shown to induce B2R expression and synergistically enhance nitrosative stress and inflammation in epithelial cells (35). Induction of activated microglial TNF-α and NO release is of particular relevance, as these pro-inflammatory cytokines are both associated with neuronal loss. iNOS expression and NO generation have been described in several brain pathologies, including AD (36). Microglial iNOS is induced by Aβ both in vitro and in vivo and activated iNOS-expressing microglia were found in amyloid plaques surrounded by dead and dystrophic neurons. Various modes and mechanisms by which NO can lead to neuronal death have been described (37, 38). TNF-α is also associated with neurodegeneration and furthermore induces the expression of amyloid precursor protein and promotes its cleavage by stimulating secretase activity to release Aβ. Reciprocally, Aβ induces TNF-α synthesis in neurons and glial cells. In addition, Aβ has been shown to physically bind TNFR-1, thereby inducing neuronal death (39).

For in vivo studies, the five familial Alzheimer’s disease (5XFAD) mouse model was employed. These mice develop rapid Aβ deposits alongside microglial accumulation beginning at 2 months of age, with plaques initially accumulate in the cortex. As shown in Figure 5, intranasal treatment of these mice with R-715 for 3.5 weeks significantly enhanced amyloid burden and CD11b expression in the cortex. Intranasal application of this B1R antagonist was chosen since this mode of delivery likely increases the direct action of the compound by bypassing the blood–brain barrier. Moreover, clinical studies involving nasal application of other compounds, such as insulin, to AD patients showed improvement in memory skills (40). However, peripheral effects of the antagonist cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the passage of peptides from nose to brain is controversial (41). Intranasal delivery of B1R or B2R antagonists has been tried here, for the first time. Similar results as those reported here were, nonetheless, reported by Passos et al., who showed that an 8 month-long treatment of triple mutant APP (Tg-SwDI) mice with R-715 resulted in enhanced amyloid burden (42). Antagonism of B1R using R-715 also resulted in significantly greater severity of multiple sclerosis in a mouse model of the disease (43). On the other hand, there is evidence suggesting a role for B2Rs in regulating brain inflammation and AD. Upregulation of B1 and B2 receptors in Aβ-infused rats was observed, mainly in brain regions such as the hippocampus and cortex, suggesting the possible involvement of kinins in AD (44). In a mouse model of AD, Prediger et al. showed improvement of cognitive deficits by genetic deletion or pharmacological antagonism of B1 or B2 receptors (45). Blockage of B2 receptor, as shown by Bicca et al., prevented Aβ-induced cognitive impairment by inhibiting brain inflammation (46). Moreover, differential roles of B1 and B2 receptors in memory consolidation were observed during aging in mice.

B1 and B2 receptors transduce their signals through similar cellular pathways. They both are generally described as signaling through Gαq and Gαi. However, B2 receptors also interact with other G proteins as well, including Gαs and Gα12/13. The signaling patterns are also different for both receptors. For example, in vascular smooth muscle cells, activating B2R induced transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ signaling, whereas B1 receptor stimulation was sustained (47). The specific way of signaling is possibly the result of different extent of regulation that these receptors are dependent on. Further studies are required to find out whether any of these differences explains differential involvement of BK receptors in modulation of amyloid burden and glial accumulation in vitro and in vivo.

To achieve better insight into mechanisms by which amyloid deposition is modulated by B1R, the effect of B1R antagonism on microglial/macrophage accumulation was investigated. R-715 distinctly augmented microglial/macrophage accumulation in the cortex of 5XFAD mice. Lee et al., similar to us, showed that reduced microglial activation was associated with less amyloid accumulation (48). Specific characterization of the microglia/macrophage phenotype(s) was not done here, although one can envision that a more complete analysis of microglial markers might point to a given functional or activation state that is more favorable for reducing amyloid accumulation.

To conclude, we have presented evidence supporting a role for B1R in brain inflammation and in the regulation of amyloid deposition in AD mice, possibly with microglial/macrophage involvement. Further studies are required to test whether modulation of this receptor can serve as a novel therapeutic strategy for AD.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel. The protocol was approved by this committee: approval number IL-30-08-2011.

Author Contributions

SF-B and KA designed the experiments. KA performed the experiments. KA and NT analyzed data and prepared figures. SF-B and KA wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors state that the study was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer, M-CT, and handling editor declared their shared affiliation, and the handling editor states that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Abraham Danon for his useful advice.

Funding

This study was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 101/11-16).

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology (2013) 80(19):1778–83. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science (2002) 297(5580):353–6. 10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med (2011) 3(77):77sr1. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging (2000) 21(3):383–421. 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00124-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol (2015) 14(4):388–405. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, Verkhratsky A. Physiology of microglia. Physiol Rev (2011) 91(2):461–553. 10.1152/physrev.00011.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji K, Akgul G, Wollmuth LP, Tsirka SE. Microglia actively regulate the number of functional synapses. PLoS One (2013) 8(2):e56293. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkhurst CN, Yang G, Ninan I, Savas JN, Yates JR, III, Lafaille JJ, et al. Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell (2013) 155(7):1596–609. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bamberger ME, Harris ME, McDonald DR, Husemann J, Landreth GE. A cell surface receptor complex for fibrillar beta-amyloid mediates microglial activation. J Neurosci (2003) 23(7):2665–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paresce DM, Ghosh RN, Maxfield FR. Microglial cells internalize aggregates of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid beta-protein via a scavenger receptor. Neuron (1996) 17(3):553–65. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80187-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart CR, Stuart LM, Wilkinson K, van Gils JM, Deng J, Halle A, et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(2):155–61. 10.1038/ni.1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Walter S, Stagi M, Cherny D, Letiembre M, Schulz-Schaeffer W, et al. LPS receptor (CD14): a receptor for phagocytosis of Alzheimer’s amyloid peptide. Brain (2005) 128(Pt 8):1778–89. 10.1093/brain/awh531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Bernhardi R, Ramirez G, Toro R, Eugenin J. Pro-inflammatory conditions promote neuronal damage mediated by amyloid precursor protein and decrease its phagocytosis and degradation by microglial cells in culture. Neurobiol Dis (2007) 26(1):153–64. 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noda M, Kariura Y, Amano T, Manago Y, Nishikawa K, Aoki S, et al. Expression and function of bradykinin receptors in microglia. Life Sci (2003) 72(14):1573–81. 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)02449-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ifuku M, Farber K, Okuno Y, Yamakawa Y, Miyamoto T, Nolte C, et al. Bradykinin-induced microglial migration mediated by B1-bradykinin receptors depends on Ca2+ influx via reverse-mode activity of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Neurosci (2007) 27(48):13065–73. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhoola KD, Figueroa CD, Worthy K. Bioregulation of kinins: kallikreins, kininogens, and kininases. Pharmacol Rev (1992) 44(1):1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai J, Luo MC, Chen Q, Porreca F. Pronociceptive actions of dynorphin via bradykinin receptors. Neurosci Lett (2008) 437(3):175–9. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruden NL, Newby DE. Therapeutic potential of icatibant (HOE-140, JE-049). Expert Opin Pharmacother (2008) 9(13):2383–90. 10.1517/14656566.9.13.2383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham WM, Scuri M, Farmer SG. Peptide and non-peptide bradykinin receptor antagonists: role in allergic airway disease. Eur J Pharmacol (2006) 533(1–3):215–21. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker K, Perkins M, Dray A. Kinins and kinin receptors in the nervous system. Neurochem Int (1995) 26(1):1–16. 10.1016/0197-0186(94)00114-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamiya T, Katayama Y, Kashiwagi F, Terashi A. The role of bradykinin in mediating ischemic brain edema in rats. Stroke (1993) 24(4):571–5. 10.1161/01.STR.24.4.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iores-Marcal LM, Viel TA, Buck HS, Nunes VA, Gozzo AJ, Cruz-Silva I, et al. Bradykinin release and inactivation in brain of rats submitted to an experimental model of Alzheimer’s disease. Peptides (2006) 27(12):3363–9. 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regoli D, Barabe J. Pharmacology of bradykinin and related kinins. Pharmacol Rev (1980) 32(1):1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calixto JB, Cabrini DA, Ferreira J, Campos MM. Kinins in pain and inflammation. Pain (2000) 87(1):1–5. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00335-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gimpl G, Walz W, Ohlemeyer C, Kettenmann H. Bradykinin receptors in cultured astrocytes from neonatal rat brain are linked to physiological responses. Neurosci Lett (1992) 144(1–2):139–42. 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90735-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarit BS, Lajos G, Abraham D, Ron A, Sigal FB. Inhibitory role of kinins on microglial nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production. Peptides (2012) 35(2):172–81. 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci (2006) 26(40):10129–40. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asraf K, Torika N, Roasso E, Fleisher-Berkovich S. Differential effect of intranasally administrated kinin B1 and B2 receptor antagonists in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Biol Chem (2016) 397(4):345–51. 10.1515/hsz-2015-0219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austinat M, Braeuninger S, Pesquero JB, Brede M, Bader M, Stoll G, et al. Blockade of bradykinin receptor B1 but not bradykinin receptor B2 provides protection from cerebral infarction and brain edema. Stroke (2009) 40(1):285–93. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Couture R, Harrisson M, Vianna RM, Cloutier F. Kinin receptors in pain and inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol (2001) 429(1–3):161–76. 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01318-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levant A, Levy E, Argaman M, Fleisher-Berkovich S. Kinins and neuroinflammation: dual effect on prostaglandin synthesis. Eur J Pharmacol (2006) 546(1–3):197–200. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noda M, Kariura Y, Pannasch U, Nishikawa K, Wang L, Seike T, et al. Neuroprotective role of bradykinin because of the attenuation of pro-inflammatory cytokine release from activated microglia. J Neurochem (2007) 101(2):397–410. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noda M, Sasaki K, Ifuku M, Wada K. Multifunctional effects of bradykinin on glial cells in relation to potential anti-inflammatory effects. Neurochem Int (2007) 51(2–4):185–91. 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleisher-Berkovich S, Filipovich-Rimon T, Ben-Shmuel S, Hulsmann C, Kummer MP, Heneka MT. Distinct modulation of microglial amyloid beta phagocytosis and migration by neuropeptides (i). J Neuroinflammation (2010) 7:61. 10.1186/1742-2094-7-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ricciardolo FL, Sorbello V, Benedetto S, Defilippi I, Sabatini F, Robotti A, et al. Bradykinin- and lipopolysaccharide-induced bradykinin B2 receptor expression, interleukin 8 release and “nitrosative stress” in bronchial epithelial cells BEAS-2B: role for neutrophils. Eur J Pharmacol (2012) 694(1–3):30–8. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown GC. Mechanisms of inflammatory neurodegeneration: iNOS and NADPH oxidase. Biochem Soc Trans (2007) 35(Pt 5):1119–21. 10.1042/BST0351119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbons HM, Dragunow M. Microglia induce neural cell death via a proximity-dependent mechanism involving nitric oxide. Brain Res (2006) 21(1):1–15. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz A, Mendieta L, Zenteno E, Guevara J, Limon ID. The role of NOS in the impairment of spatial memory and damaged neurons in rats injected with amyloid beta 25-35 into the temporal cortex. Pharmacol Biochem Behav (2011) 98(1):67–75. 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang WY, Tan MS, Yu JT, Tan L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Transl Med (2015) 3(10):136. 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freiherr J, Hallschmid M, Frey WH, II, Brunner YF, Chapman CD, Holscher C, et al. Intranasal insulin as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease: a review of basic research and clinical evidence. CNS Drugs (2013) 27(7):505–14. 10.1007/s40263-013-0076-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leng G, Ludwig M. Intranasal oxytocin: myths and delusions. Biol Psychiatry (2016) 79(3):243–50. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Passos GF, Medeiros R, Cheng D, Vasilevko V, Laferla FM, Cribbs DH. The bradykinin B1 receptor regulates Abeta deposition and neuroinflammation in Tg-SwDI mice. Am J Pathol (2013) 182(5):1740–9. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulze-Topphoff U, Prat A, Prozorovski T, Siffrin V, Paterka M, Herz J, et al. Activation of kinin receptor B1 limits encephalitogenic T lymphocyte recruitment to the central nervous system. Nat Med (2009) 15(7):788–93. 10.1038/nm.1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viel TA, Lima Caetano A, Nasello AG, Lancelotti CL, Nunes VA, Araujo MS, et al. Increases of kinin B1 and B2 receptors binding sites after brain infusion of amyloid-beta 1-40 peptide in rats. Neurobiol Aging (2008) 29(12):1805–14. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prediger RD, Medeiros R, Pandolfo P, Duarte FS, Passos GF, Pesquero JB, et al. Genetic deletion or antagonism of kinin B(1) and B(2) receptors improves cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience (2008) 151(3):631–43. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bicca MA, Costa R, Loch-Neckel G, Figueiredo CP, Medeiros R, Calixto JB. B(2) receptor blockage prevents Abeta-induced cognitive impairment by neuroinflammation inhibition. Behav Brain Res (2015) 278:482–91. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathis SA, Criscimagna NL, Leeb-Lundberg LM. B1 and B2 kinin receptors mediate distinct patterns of intracellular Ca2+ signaling in single cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol (1996) 50(1):128–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee DC, Rizer J, Hunt JB, Selenica ML, Gordon MN, Morgan D. Review: experimental manipulations of microglia in mouse models of Alzheimer’s pathology: activation reduces amyloid but hastens tau pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol (2013) 39(1):69–85. 10.1111/nan.12002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]