Abstract

Pancreatic duct glands (PDG) have molecular features known to mark stem cell niches, but their function remains to be determined. To investigate the role of PDG as a progenitor niche, PDG were analyzed in both humans and mice. Cells were characterized by immunohistochemistry and microarray analysis. In vivo proliferative activity and migration of PDG cells were evaluated using a BrdU tag-and-chase strategy in a mouse model of pancreatitis. In vitro migration assays were used to determine the role of trefoil factor (TFF) −1 and 2 in cell migration. Proliferative activity in the pancreatic epithelium in response to inflammatory injury is identified principally within the PDG compartment. These proliferating cells then migrate out of PDG compartment to populate the pancreatic duct. Most of the pancreatic epithelial migration occurs within 5 days and relies, in part, on TFF-1 and -2. After migration, PDG cells lose their PDG-specific markers and gain a more mature pancreatic ductal phenotype. Expression analysis of the PDG epithelium reveals enrichment of embryonic and stem cell pathways. These results suggest that PDG are an epithelial progenitor compartment that gives rise to mature differentiated progeny that migrate to the pancreatic duct. Thus PDG are a progenitor niche important for pancreatic epithelial regeneration.

Keywords: Pancreatic duct glands, PDG, progenitor niche, stem cell compartment, trefoil factor, epithelial regeneration

INTRODUCTION

Maintenance and repair of most epithelia are achieved by stem cells, which must undergo cell division in order to self-renew and must also be capable of cell division, resulting in daughter cells that migrate and differentiate into multiple lineages of the particular epithelium [1–3]. The pancreatic epithelium is thought to have a low turnover rate under normal physiologic conditions [4, 5]; however, it is capable of rapid regeneration in response to inflammatory injury [6, 7]. The existence of somatic stem cells and their contribution to pancreatic epithelial renewal and regeneration after injury are poorly understood.

Perhaps some of the best studied models of epithelial regeneration from a somatic stem cell niche are the GI system[8–11]. The liver has a low rate of cellular turnover but high regenerative potential. Its parenchyma relies initially on a mechanism of self-duplication, and relies on stem cells, ductular oval cells, only when hepatocyte division is inhibited. In the intestinal system, the epithelial turnover occurs every 3–5 days, while Paneth cells are supplied every 3–6 weeks. Epithelial stem cells exist in a protected microenvironment called niches. These niches contain several different cell types initially defined by their proliferative properties. The label retaining cell (LRC), likely the true stem cell, which normally has a lower rate of division but can transform into a proliferative and multipotential stem cell during injury. The transient amplifying (TA) cell which is believed to be a direct progeny of the true stem cell and are capable of division but for a restricted period of time [2, 12]. Despite their extensive characterization of these stem cell niches in the colon and small intestine, only a few molecular markers for these cells have been identified. Several studies strongly implicate Lgr5 and Lrig1 as markers and regulators of the stem cell compartment [13].

Epithelial regeneration and renewal from progenitor niches throughout the gastrointestinal system requires a complex balance of proliferation, migration and differentiation. As newly generated cells migrate from the stem cell compartment they differentiate to acquire the phenotype of their terminally differentiated lineages. This migration is regulated, in part, by the Trefoil Factor Family (TFF) of proteins. There are three members within this family TFF-1, TFF-2 and TFF-3. All TFF are protease resistant proteins, which are best known for their important roles in epithelial repair after inflammatory injury [14, 15]. The TFFs are abundantly secreted onto the mucosal surface by mucus-secreting cells of the gastrointestinal tract and the pancreatic duct [16, 17]. In the stomach the expression of TFF-1 and -2 is rapidly up-regulated at the margin of mucosal injury, and their fundamental function is to promote epithelial repair by cell migration

The identification of stem cells or progenitor cells, and their contribution to pancreatic regeneration remain controversial [18, 19]. The pancreas uses several regenerative mechanisms. Self-renewal are the principal mechanism of acinar and islet regeneration in response to inflammatory injury[20–22], however, little is known about pancreatic ductal epithelial renewal. Multipotential stem cells have been reported to reside in the pancreatic duct [5], islets, centroacinar or acinar cells and have the capacity for duct-like cell fates. [23–27]. Recently our group identified a novel epithelial compartment, termed pancreatic duct glands (PDG), which may function as a ductal epithelial progenitor niche [28]. PDG are gland-like outpouches or coiled glands residing within the mesenchymal cuff of surrounding large ducts. PDG have a unique molecular profile distinct from glands of the normal pancreatic epithelium. They also express developmental markers known to reside in GI progenitor stem cell niches, such as Shh, Pdx-1 and Hes-1. In response to inflammatory injury, epithelial proliferation is up-regulated predominantly in the PDG compartment, suggesting that this may be an epithelial progenitor compartment for the pancreatic ductal epithelium.

In this study, we find that the PDG are the principal site of ductal proliferation in response to acute inflammatory injury. Trefoil family factors −1 and −2 (TFF-1, TFF-2) promote the migration of newly generated cells from PDG to the pancreatic ductal epithelium. Furthermore, PDG compartment is enriched for pathways important in embryonic and GI stem cell niches. These results suggest that PDG constitute an epithelial progenitor niche important in the repair of the pancreatic duct after inflammatory injury.

METHODS

Human samples

Human samples were collected and analyzed in accordance with Institutional Review Board approval. Normal control pancreata (n=14) were obtained from organ donors and chronic pancreatitis samples (n=20) were obtained from pancreatectomy specimens at Massachusetts General Hospital. No patients were included who carried a diagnosis of IPMN or PDAC.

Mouse samples

All experiments were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care (SRAC # 2003N000288). Healthy FVB mice (Charles River) served as control (n=7). Acute pancreatitis was induced in FVB mice of either sex by cerulein injection every other day for 8 days (4 injections) (n=21). Each series of injections comprises 8 hourly intraperitoneal injections of 50µg/kg cerulein (Sigma, St Louis, MO). In vivo pulse labeling was performed by intraperitoneal injection of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma) at 1mg/10g body weight 24 hours after the last cerulein injection. Pancreata were harvested 2 hours after BrdU injection then daily for 7 days, with additional harvest on day 14 and 21. Positive and negative nuclei were counted through the large pancreatic duct multiple slides per mouse, approximately 30 HPF per sample where evaluated to calculate the rate of BrdU positive cells in the ducts and PDG. This BrdU tag-and-chase technique was repeated in TFF2 knockout mice[29, 30] (n=12, kind gift of Dr. Wang (Columbia University)) and evaluated. The pancreata obtained from Lgr-5; EGFP mice[31] (n=4) were evaluated to investigate the existence of Lgr5 in the PDG compartment.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Specimens were fixed overnight in 10% formalin/phosphate-buffered saline. Histological analysis was performed on 4µm paraffin-embedded sections. Primary antibodies and conditions for immunohistochemistry are specified in Table 1. Biotinylated secondary antibodies were applied at 1:1000 dilution. Proteins were visualized by using diaminobenzidine peroxidase (DAB) substrate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. For immunofluorescent staining, secondary antibodies were applied at 1:500 dilution and slides were counterstained by 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Table 1.

Conditions and primary antibodies for immunohistochemistry.

| protein of interest | species | antibody by | clone | concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFF1 | human | invitrogen | BC04 | 1:50 |

| TFF1 | human and mouse | abcam | ab50806 | 1:200 |

| TFF2 | human | Novocastra | GE16C | 1:50 |

| TFF2 | human and mouse | Protein Tech | 1:500 | |

| MUC6 | human | Novocastra | NCL-MUC-6 | 1:100 |

| deep gastric mucin (MUC6) | mouse | Dr. Ho | 1:3000 | |

| KRT7 | human and mouse | abcam | RCK105 | 1:50 |

| Ki67 | human | Dako | MIB-1 | 1:100 |

| Ki67 | mouse | Dako | TEC3 | 1:25 |

| Ki67 | mouse | abcam | ab16667 | 1:100 |

| BrdU | mouse | abcam | ab6326 | 1:100 |

Cell culture study

Human pancreatic ductal epithelial (HPDE)[32, 33] cells were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free media supplemented with bovine pituitary extract and human epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen). Control vector (pCMV-SPORT6) and TFF1-overexpression plasmid (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were transfected into HPDE cells using FuGene6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

In vitro migration assay

After the transfection of TFF1 and control vector, an artificial wound was created by manually scraping confluent monolayer cells with micropipettes tips. Dishes were incubated for 24 hours and the status of the gap closure was observed. 20 images were acquired randomly and analyzed quantitatively by calculating the cell-empty area using ImageJ (public domain NIH image software).

Cell proliferation assay

HPDE cells were planted on 96-well plates (1000 cells per well), followed by the transfection of control, TFF1-overexpressing plasmid. Five days after transfection, relative cell number was calculated by resazurin (R&D Systems) using plate reader (Spectramax M2, Molecular Devices) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RT-PCR

Total RNA (1µg) was extracted from cultured cells using RNA extraction kit (RNeasy Mini; Qiagen) and used to synthesize cDNA (ThermoScript PT-PCR System; Invitrogen). PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 50µl containing 2µl of cDNA, 2mM MgCl2, 200µM dNTP Mix, 0.2µM each of 5´- and 3΄- primers, and 1U of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with an annealing temperature of 60°C. The sequence of the TFF1 primers is 5´-CAGACAGAGACGTGTACAGTGGCCC-3´ (forward) and 5΄-AGCGTGTCTGAGGTGTCCGGT-3´ (reverse). The number of PCR cycles was 34. For each reaction, an initial denaturation cycle of 94°C and a final cycle of 72°C were incorporated. The PCR products were subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. 18S RNA was used as internal control.

Microarray Analysis

Approximately 1,000 cells from PDG and pancreatic main duct epithelium from two organ donors were laser captured and microdissected with Arcturus PixCell IIe. RNA was purified using an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and amplified with the Ovation® PicoSL WTA System V2 (NuGEN Technologies). RNA isolated from cells obtained by LCM was quantified using a nanodrop (Thermo Scientific) and RNA quality assessed using a Bionanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Amplified RNA was labeled with Encore™ BiotinIL Module (NuGEN Technologies) and hybridized to the HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip (Illumina). Up-regulated genes in PDG compared to the main duct were filtered using a cut off of p≤ 0.05 and a fold change ≥ 1.5 for both organ donors. Analysis was performed using GSEA (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). Gene expression data from intestine (GSE10629) and colon (GSE6894) was analyzed with GEO2R (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). Up- regulated genes in intestinal crypts vs. intestinal villi and colon crypt bottom vs. top were determined by p ≤ 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2. PDG gene expression values were visualized with Gene Pattern HeatMapImage (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern/).

Statistics

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS-II software. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using ANOVA. When the P-value was ≤0.01, the difference was regarded as significant.

RESULTS

PDG are the principal site of epithelial regeneration of the pancreatic ductal epithelium

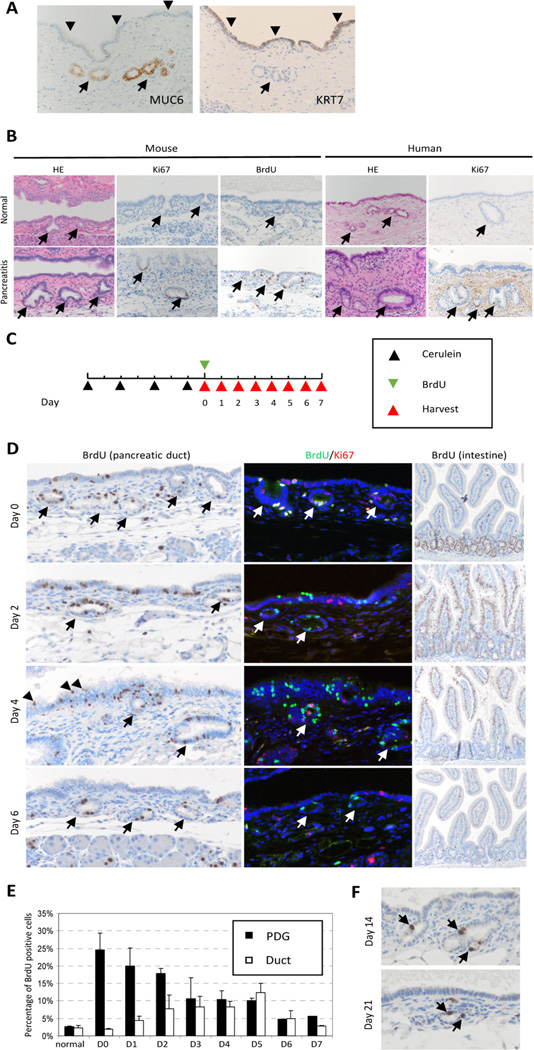

PDGs are gland-like outpouches budding off the main pancreatic duct. These glands reside in the mesenchymal cuff that surround larger pancreatic ducts. PDG are identified to be uniquely different form the overlying pancreatic epithelium not only by morphology and location but also by their molecular signature [28]. For example MUC6 is strongly expressed in PDG but not in ductal epithelium, while KRT7 is not expressed in PDG but in ductal epithelium (Fig 1A). The normal pancreatic ductal epithelium has a low rate of proliferation. Cerulein pancreatitis results in inflammatory injury to the pancreatic epithelium with inflammatory cells around the ducts and within the pancreatic epithelium (Fig. S1). In response to acute inflammatory injury there was, as previously reported, a 40% BrdU incorporation into the acinar cells [20], however, there was also a marked up-regulation of BrdU incorporation and increased expression of the proliferative marker Ki-67,in the epithelia, identified predominantly within the PDG compartment (Fig. 1B). In order to establish PDG as the site of epithelial ductal regeneration and renewal, in vivo BrdU tag-and-chase experiments were employed to fate-map tagged cells. In this model (Fig. 1C) proliferating cells are pulse-labeled with BrdU on day 0 after acute inflammatory injury; then pancreata were harvested daily over the chase period of 7 days and then at 14 and 21 days. Qualitative (Fig. 1D) and quantitative (Fig. 1E) analyses revealed a dynamic shift of BrdU-positive cells from the PDG to the ductal epithelium over the chase period. There was a gradual decline in the number of BrdU-positive cells within the PDG compartment, from a peak of 25% on day 0 to 5% by day 6 (Fig. 1D, 1E). Interestingly, some cells within the PDG compartment retain their label even up to 21 days (1.06% of PDG cells; Fig. 1F). In contrast, BrdU cells within the pancreatic ductal compartment gradually increased from its baseline of 2.5% on day 0 to a peak of 12.5% on day 5. By day 4, BrdU-tagged cells were identified on the top of stratified epithelia (Fig. 1D, arrowheads), suggesting that these cells are being shed into the lumen. By day 6, the majority of the BrdU-tagged cells were no longer identified within the pancreatic ducts.

Figure 1. Tag and chase reveals a dynamic shift of PDG cells.

(A) molecular characteristics of PDG. MUC6 is expressed only in PDG (arrow) but not in ductal epithelium (arrowhead), while KRT7 expressed in ductal epithelium but not in PDG. (B) PDG (arrow) is the principal site of proliferation. In response to injury, there is a marked up-regulation of BrdU incorporation and increased expression of the proliferative marker Ki-67. (C) Scheme of BrdU tag-and-chase experiment. BrdU was injected to mark proliferating cells on day 0, and mouse pancreata were harvested daily over the chase period of 7 days. (D) Qualitative analysis of BrdU-tagged cells. BrdU tags PDG cells (arrow) initially, then tagged cells migrate out into duct epithelium, and some of them are shed into the lumen (arrowhead). Double staining of BrdU and Ki67 shows that double-positive cells were found only on day 0. The intestine show the typical dynamics of BrdU positive cells, which migrate from the crypt toward the surface then disappear. (E) Quantitative analysis of BrdU-positive cells shows a dynamic shift of BrdU-positive cells from PDG to the ductal epithelium. (F) A few BrdU-positive cells (arrow) remain in PDG for up to 21 days. Original magnification × 200 (except for intestine; × 100).

In order to determine if the BrdU-label is lost by continued proliferation after the initial tagging event or after migration into the pancreatic duct, double immunostaining for Ki-67 and BrdU was performed. In this model, BrdU detects cells that were proliferating during the initial tag and Ki-67 detects cells presently proliferating (Fig. 1D). While double-positive nuclei are found within the PDG compartment on day 0, over the chase period BrdU-positive cells are not found to be Ki-67 positive. Ki-67 cells can occasionally be found in the PDG compartment after day 0, but not in previously tagged BrdU cells. This data suggests that cells in the PDG compartment generate their descendants for only a restricted period of time, just after inflammatory injury. Furthermore, these descendants (migrated BrdU-positive cells) do not continue to proliferate. These results suggest that PDG are the compartment from which newly generated cells migrate to regenerate and renew the pancreatic ductal epithelia.

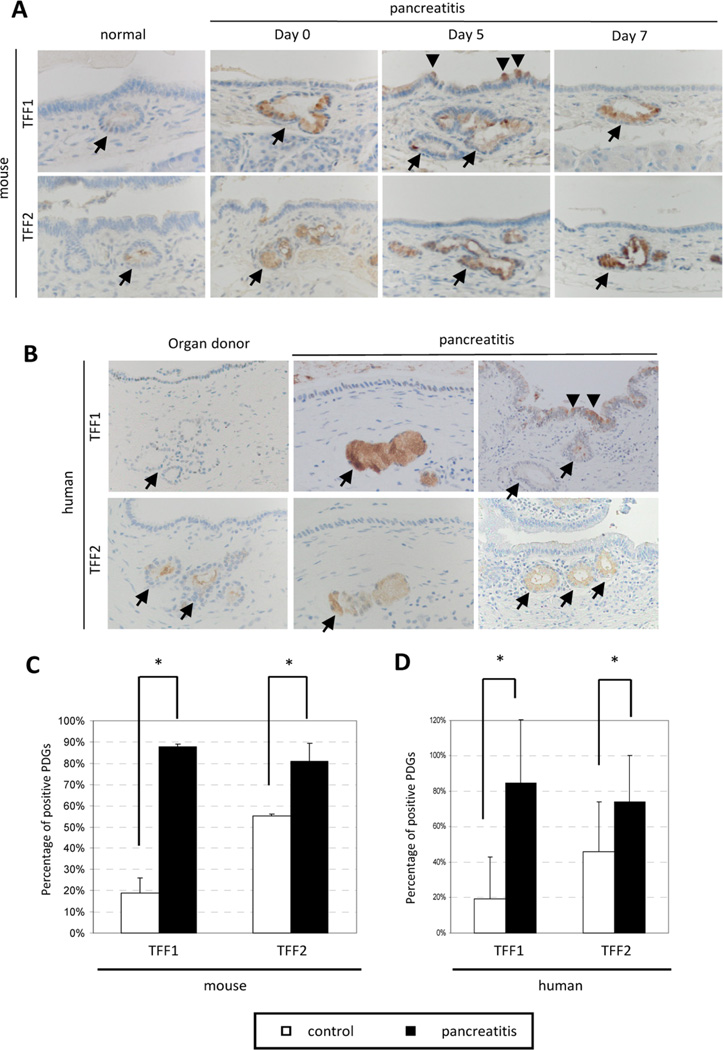

Migration of pancreatic epithelial cells is regulated by TFF

The trefoil factor family (TFF), a family of protease-resistant secreted factors, plays an essential role in epithelial migration. To investigate the contribution of TFF family members to the migration of epithelial cells from the PDG to the main duct, immunohistochemistry of TFF1 and TFF2 were performed in both mouse and human pancreata (Fig. 2A and B). In normal pancreata, TFF1 was expressed at a low level and identified in only a few cells throughout the ductal epithelium and PDG compartment (18.8% in normal mice, 19.4% in human organ donors). Similarly, TFF2 is expressed at a very low level, but its expression is restricted to the PDG compartment, where it is identified in almost half of the PDG (55.0% in normal mice, 54.8% in human organ donors). In response to inflammatory injury, TFF1 and TFF2 expression is significantly up-regulated. The up-regulation of TFF1 is evidenced not only by the enhanced staining within the PDG and surrounding pancreatic ductal epithelium, but also by a significant increase (p<0.001) in the total number of TFF1-positive PDG (87.7% in mice and 84.7% in humans) (Fig. 2C and D). Similarly, TFF2 shows enhanced staining as well as a statistically significant increase (p<0.01) in total number of TFF2-positive PDG (80.9% in mice and 74.2% in human samples). TFF2 expression remains restricted to the PDG compartment after the inflammatory injury (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2. TFF are expressed in injured PDG.

(A, B) Immunohistochemistry of TFF1 and TFF2 in mouse and human specimens. In normal pancreata, TFF1 is expressed at a low level and identified in only a few cells throughout the ductal epithelium and PDG compartment (arrow). Similarly, TFF2 is expressed at a very low level. In response to inflammatory injury, both TFF1 and TFF2 expression is significantly up-regulated. While TFF1 expression is found in both PDG and duct epithelium (arrowhead), TFF2 expression distribution is restricted to the PDG compartment. Original magnification x400 (mouse), x200 (human) (C, D) Quantitative analysis of TFF-positive PDGs in mouse and human specimen. Both TFF1 and TFF2 are expressed significantly higher in injured pancreas (TFF1: 18.8% and 87.7% (mouse), 19.4% and 84.7% (human); TFF2: 55.0% and 80.9% (mouse), 54.8% and 74.2% (human) in control and pancreatitis, respectively). Data are shown as means +/− SD. (* p<0.01)

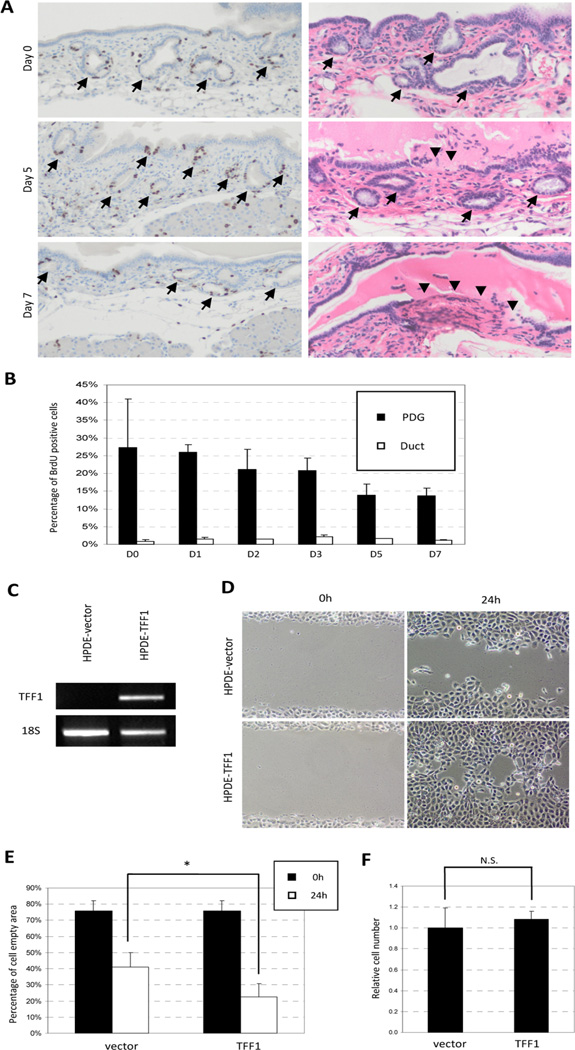

To determine whether TFF1 and TFF2 contribute to pancreatic epithelial cell migration, in vivo pulse chase experiments and in vitro migration assays were performed (Fig. 3). To evaluate the role of TFF2 in cell migration, we took advantage of a genetically engineered mouse deficient in TFF2 (TFF2-KO). In vivo pulse-chase experiments on TFF2-KO animals were repeated as previously described in normal mice. Qualitative (Fig. 3A) and quantitative (Fig. 3B) analyses revealed that the PDG compartments are the principal site of proliferation and have a peak frequency of 25% of tagged PDG cells on day 0 after inflammatory injury, which is similar to the tagging efficiency seen in normal controls. However, over the chase period of 7 days there was no dynamic shift of BrdU-positive cells from the PDG to the ductal epithelium. Pulse-chase experiments in TFF2KO animals revealed a persistence of BrdU label in the PDG compartment and no increase in BrdU-labeled cells in the ducts. These mice not only reveal decreased migration of cells from the PDG but also contain ulcerations of the main duct. These ulcerative lesions were initially seen on day 3 and became more pronounced by days 5–7 (Fig. 3A). These experiments demonstrate that the loss of TFF2 decreases migration (not proliferation), resulting in insufficient epithelial repair and ulceration.

Figure 3. Migration of pancreatic ductal epithelial cells is regulated by TFF.

(A) Qualitative analysis of in vivo pulse-chase experiments on TFF2-KO mice. BrdU-positive cells remain in the PDG (arrow) compartment over the chase period of 7 days. Ulceration of the pancreatic duct can be seen on day 5 and day 7 (arrowhead). (B) Quantitative analysis shows no dynamic shift of BrdU-tagged cells. (C) HPDE cells were transfected with control and TFF1-expression vector. The transcriptions of TFF1 were confirmed by RT-PCR. (D) TFF1-HPDE cells migrate into artificial wound more rapidly than control cells. (E) Quantitative analysis of the “cell-empty area.” TFF1-transfected cells resulted in a significantly smaller empty area (53.8% vs 29.6%, * p<0.01). (F) Proliferative activity of HPDE cells by resazurin assay. TFF1-transfected cells show no difference in proliferative activity.

In the absence of an available animal model, in vitro migration experiments were performed in order to determine the role of TFF1 in pancreatic ductal epithelial cell migration. HPDE cells were transfected with either control, or TFF1-expression vector and migration was evaluated by creating a cell free area, an artificial “wound”, on confluent HPDE cells (Fig. 3C and D). Transfection efficiency of the TFF-1 was approximately 50%. Migration of cells to the cell-free region was observed at 24 hours and images were captured (Fig. 3D). While HPDE with control vector shows 50% closure of the cell-free region, TFF1-transfected cells are found to significantly enhance migration ability (Fig 3E; 70% of the cell-empty area was healed, p<0.0001). To exclude the possibility that this healing of the cell free area was due to cell proliferation rather than cell migration, the ability of cell proliferation was assessed by resazurin assay (Fig. 3F). TFF1-expressing HPDE cells show proliferative activity similar to control, suggest that the in vitro cell free area was healed by the migration of the cells, rather than cell proliferation. Together, the in vitro and in vivo data suggests that up-regulation of TFF1 and TFF2 seen in the PDG and in the normal ductal epithelia likely functions to promote migration.

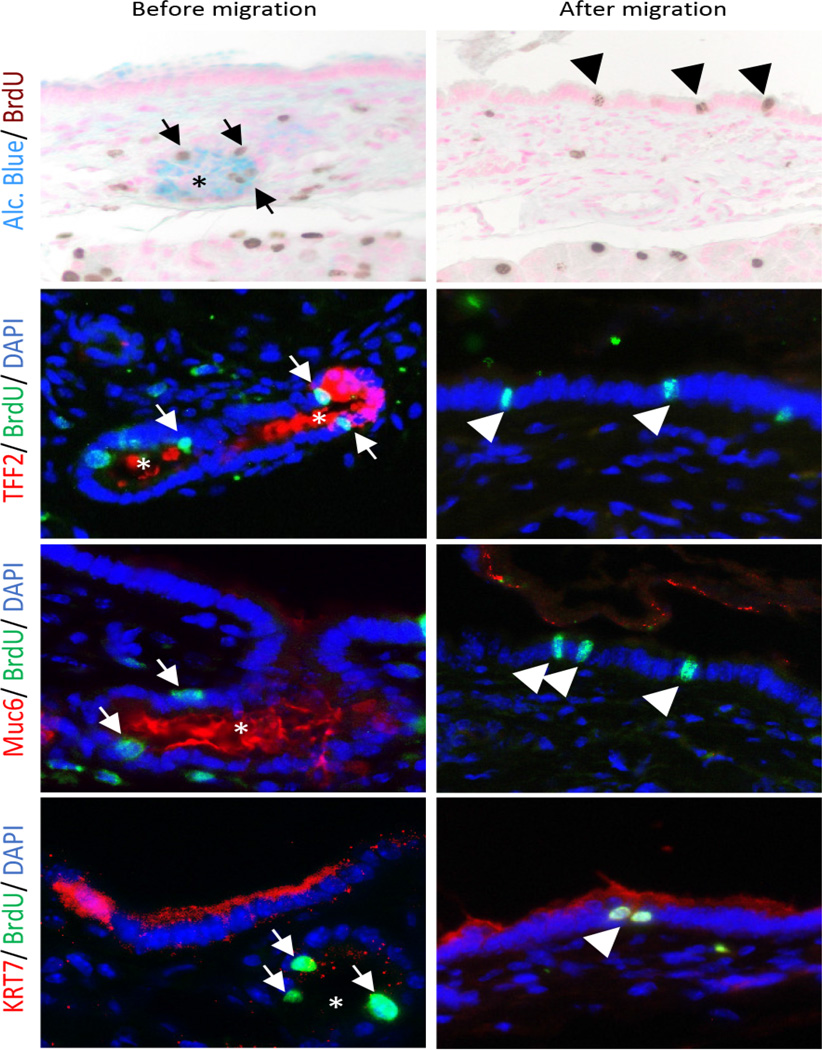

PDG give rise to differentiated progeny

Stem cell niches are not only characterized by the presence of proliferative compartments from which cells migrate; these compartments must also have the ability to give rise to mature differentiated progeny distinct from the parent progenitor. Thus if PDG are pancreatic ductal epithelial progenitor niches, migrated BrdU-positive epithelial cells found in the pancreatic ducts should express molecular markers unique from BrdU-positive cells of the PDG. In order to evaluate the differentiation of PDG cells during their migration, double IHC and IF were performed. Before migration, BrdU-positive cells within the PDG compartment express Alcian blue-positive mucin, TFF2 and deep gastric mucin (Muc6) (Fig. 4, left panel, arrow). After migration, BrdU-positive cells in the ductal epithelium have lost their expression of these PDG markers (Fig. 4, arrowhead), and have acquired the expression of a mature pancreatic duct-specific marker, KRT7, which was not expressed in the PDG compartment. Although these findings remain to be confirmed with formal lineage tagging experiments, the changes in molecular characteristics of BrdU-tagged cells suggest that PDG are capable of producing differentiated progeny, supporting its role as a progenitor epithelial niche.

Figure 4. PDG give rise to differentiated progeny.

Identification of molecular characteristics of BrdU-tagged cells before migration (day 0, arrow) and after migration (day 5, arrowhead) in mouse. During their migration, BrdU-tagged cells lose their initial expression of PDG-specific markers (Alcian blue, TFF2 and Muc6) but acquire the expression of a mature pancreatic duct-specific marker, KRT7. Original magnification ×400.

Microarray analysis reveals that the PDG compartment expresses stem cell markers

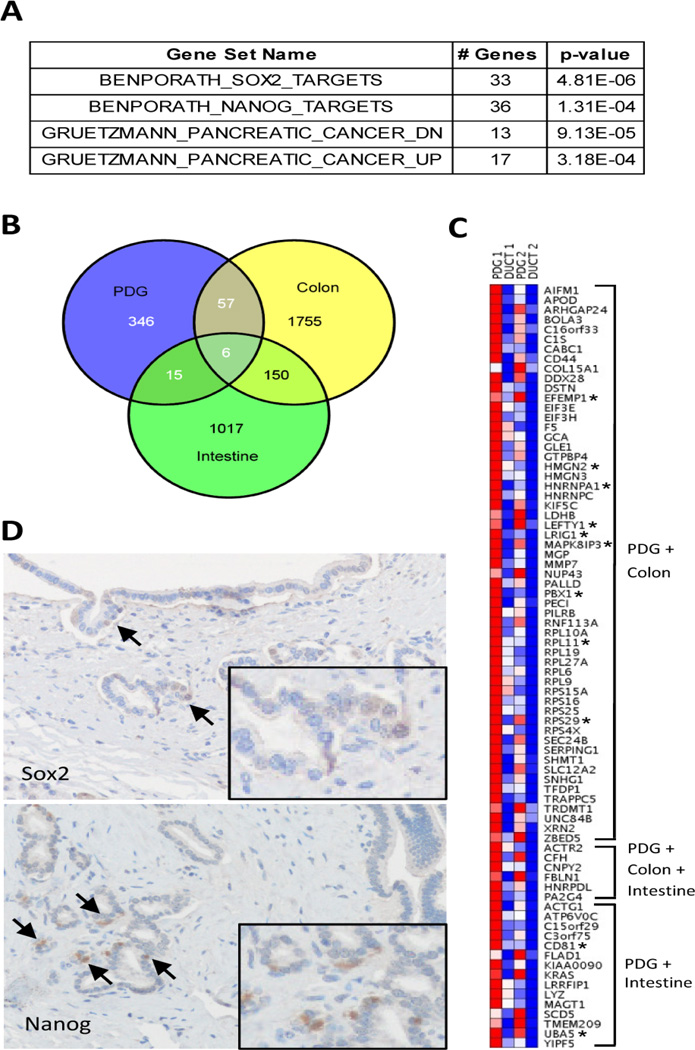

Minimal sample microarray analyses from LCM of PDG epithelium compared to their matched normal pancreatic ducts reveal that PDG cells are enriched for previously identified stem cell genes (Fig. 5). Differentially expressed genes were identified using a p≤0.05 and a ≥1.5-fold change (Table S1). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed that the Sox2 and Nanog pathways, core regulators of embryonic stem cell (ECS) pluripotency, were enriched in the PDG compartment (Fig. 5A). GSEA analysis identified 33 SOX2 and 36 NANOG target genes are up regulated in PDG (Table S2). Comparing our PDG data set with other published stem cell data sets, we found that PDG were also enriched for genes found in intestinal and colonic stem cells (Fig. 5B). In order to validate the GSEA analysis, IHC was performed on human specimens for the two core regulators pathways enriched in the PDG microarray. Both SOX2 and Nanog were identified by IHC in the PDG compartment. This low level of expression was identified in a subset of cells within the PDG compartment (Fig. 5D). This data suggests that SOX2 and the NANOG and/or their downstream effector pathways may play a role in the regulation of this compartment. Thus this lineage-restricted progenitor compartment expresses several markers known to be important in embryonic and somatic stem cell compartments. Of note, LGR5 was not identified in our PDG microarray analysis; however, because it is a well-characterized stem cell marker in the stomach and intestine, we did investigate its expression. Both IHC of LGR5 and the analysis of Lgr5-eGFP mice also failed to identify Lgr5 expression in the PDG compartment (data not shown), suggesting that progenitor cells within the PDG do not express Lgr5. Interestingly, the compartment also was found to be enriched for pathways known to be important in pancreatic cancer (Table S3), suggesting not only that this compartment is a progenitor niche but that dysregulation of the PDG compartment may result in pancreatic malignancy.

Figure 5. Micorarray analysis of RNA from PDG and main duct epithelium of normal pancreas.

(A) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the 424 genes up-regulated in PDG demonstrates significant enrichment of Sox2 and Nanog target genes, as well as genes with altered expression in pancreatic cancer. The gene set name, number of PDG up-regulated genes in the gene set, and p-value are shown. (B) Venn diagram comparing genes enriched in PDG and the crypts of the intestine and colon. (C) Heatmap representation of genes enriched in PDG that are also enriched in intestinal and/or colon crypts. Genes implicated in the biology of stem or progenitor cells are denoted by an asterisk. (D) The expression of SOX2 and nanog in PDG compartment were confirmed within PDG (arrow). Inlet shows higher magnification of positive cells.

DISCUSSION

The existence of somatic stem cells in the pancreas and their contribution toward pancreatic epithelial renewal and regeneration after injury are poorly understood. Here we report that PDG, a novel epithelial compartment [28], function as a pancreatic ductal epithelial progenitor niche. This work reveals that the PDG are the principal site of epithelial proliferation and new cell formation. In vivo tag-and-chase experiments reveal that these newly generated cells migrate from the PDG to populate the pancreatic ductal epithelium. Furthermore, this compartment is capable of giving rise to differentiated progeny distinct from the parent cell. The genes expressed in this unique compartment are found to be enriched for core regulators of embryonic stem cell pluripotency and genes important in intestinal and colonic stem cells regulation. Taken together, this data suggests that the PDG are a progenitor stem cell compartment responsible for pancreatic ductal epithelial regeneration.

The pancreas may employ several regenerative mechanisms, depending on the compartment. Like the liver, the pancreatic acinar and beta cell compartments regenerate by self-duplication. Although a population of ALDH1 centroacinar/terminal ductal cells has been identified and found to have multipotential function [24], in vivo lineage tagging studies by our group and others demonstrate that the principal mode of regeneration of the islets and acinar compartment in response to inflammatory injury is dependent not on stem cells but rather on self-duplication [20–22]. The pancreatic ductal epithelium, however, appears to be more like the gastrointestinal epithelium, relying on a stem cell niche for regeneration.

Although BrdU incorporation and the tag-and-chase experiment suggest that the pancreatic ductal epithelium is regenerated from the PDG compartment, this methodology does have limitations and lineage tagging studies will ultimately be needed to make definitive conclusions. In this inflammatory model the pancreatic epithelium has several proliferating (BrdU incorporating) compartments: the PDG (found in the proximal and central pancreatic ductal epithelium), the terminal ducts, islets and the acinar cells. In vivo lineage tracing of the acinar and beta cell compartments reveal that tagged events were never identified in the pancreatic ductal epithelium, suggesting that the acinar cells nor beta cells are not capable of regenerating the ductal epithelium [20] [21]. The PDG appear to be important in regenerating the proximal to distal pancreatic ductal epithelium. However, the pancreatic epithelium is heterogeneous, and the contribution of the PDG to regeneration of the terminal ducts remains unknown. Although PDG have been found throughout the pancreas, PDG-like cells have not been identified in the terminal duct system [28]. In response to inflammatory injury, terminal ducts themselves possess a high proliferative rate[20]; thus the mechanism of regeneration of the terminal ducts likely does not rely on the PDG compartment.

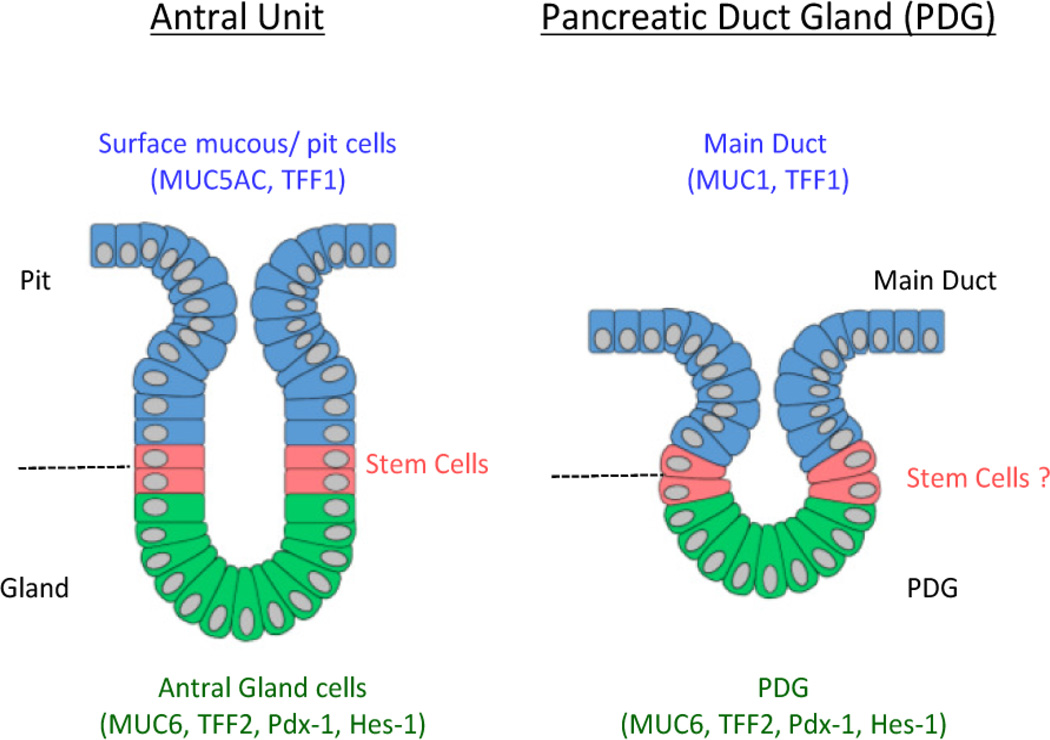

PDG possess a specific architecture and molecular signature that make them distinct from the pancreatic epithelium, instead resembling gastric stem cell glands. PDG were also found to express and up-regulate TFF genes during injury. In the stomach TFF1 is normally found predominantly in the epithelium of the surface pit of the stomach and TFF2 is primarily present in the neck region of the antral and pyloric glands of the stomach. TFF and mucins are co-expressed in gastric mucosa, such that MUC6/TFF2 are confined to the basal part of the gastric gland [15, 34]. This distribution of TFF2 and co-expression of MUC6 are also seen in the PDG niche. This molecular signature and the cellular organization and proliferative activity within the PDG are reminiscent of the GI crypts/glands, most specifically the antral gland of the stomach (Fig. 6). The similarities between the gastric glands and PDG may also extend to their functional roles in regeneration and repair in response to inflammatory injury. In stomach, the induction of trefoil-gene transcription occurs early after inflammatory injury and is considered to be important in migration of epithelial cells[35, 36]. In the PDG we also see an up-regulation of TFF1 and TFF2. Although the functional role of TFF in the pancreas is still not fully elucidated, our work suggests that TFF1 and TFF2 play an important role in regulating cell migration from the PDG compartment.

Figure 6. PDG and GI stem cell niches share similar organization and function.

Comparisons between PDG (right) and the antral glands of the stomach (left).

Stem cell niches in the GI system are also known to contain several different populations of cells, including actively dividing stem cells, transient amplifying cells (TA), and label-retaining cells (LRC). TA cells will actively divide, expanding the epithelial population for a defined period of time, while LRC have a low rate of proliferative activity but become activated during injury to be reverse stem cells [2, 12, 37, 38]. The experiments described in our study suggest that the PDG compartment is likely composed of two populations of proliferating cells. There appears to be one population of rapidly dividing cells whose presence is demonstrated by the persistence of Ki-67. Thus a proportion of the proliferating cells found in PDG behave like transient amplifying cells. The second population of cells has a much lower rate of proliferation and will initially tag, retain their BrdU label, and stay within the PDG compartment. These cells are similar to the label-retaining cells (LRC) initially described by Bickenbach in 1981 [39]. Given that only 1% of PDG cells were found to be slowly dividing cells, most of the cells tagged by BrdU are short-lived progenitors. Although the exact functional role of these cells remains to be determined, what is clear is that this compartment is composed of cells with differing proliferative potential.

Stem cells and cancer share many properties. Mutations or dysregulation of pathways within the stem cell compartment are thought to contribute to the formation of cancer. One example is the Hedgehog (Hh) pathway, which has been shown to play a role in lineage determination, maintenance of stem cell niches, and pancreatic regeneration [28, 40]. Its aberrant up-regulation is found in PDAC specifically within the pancreatic cancer stem cells (CSC)[41, 42]. It is interesting to note that cells in the PDG progenitor niche and pancreatic cancer stem cells (CSC) share similar features. Our GSEA microarray analysis not only identified this compartment to be enriched for stem cell pathways; it also showed it to be enriched for pathways dysregulated in pancreatic cancer. Although much work needs to be done to determine the role of the PDG as the site of origin for pancreatic neoplasia, what this work does reveal is that the PDG are the site of epithelial proliferation from which differentiated progeny migrate to regenerate and renew the pancreatic epithelium in response to inflammatory injury. Thus PDG are an epithelial progenitor niche important for pancreatic ductal epithelial regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

PDG are the principal site of proliferation of pancreatic ductal epithelium.

Newly generated cells show dynamic shift from the PDG to the ductal epithelium.

Progeny express differentiated epithelial markers.

Migration of these cells is in part regulated by trefoil factors −1 and −2.

PDG compartments enrich for embryonic and somatic stem cell pathways.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Andrew L. Warshaw, MD Institute for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, and by NIH-P01CA117969 to SPT. We would like to Thank Dr Timothy Wang, Dorothy L. and Daniel H. Silberberg Professor of Medicine and Chief, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Columbia University, for kindly providing TKK2 knockout mice.

Abbreviations

- PDG

pancreatic duct glands

- TFF

trefoil factor family

- CSC

cancer stem cells

- CK

cytokeratin

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- IF

immunofluorescence

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LRC

label-retaining cells

- TA

transient amplifying cells

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There is no conflict of interest.

Contributors: JPY, ASL, AS, SPT: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, interpretation of data, manuscript writing. SPT, CFC, ALW: administrative support. MMK: data analysis and interpretation of pathology. SPT: final approval of manuscript.

Supporting information:

Figure S1. Ductal inflammation caused by cerulein.

References

- 1.Barker N, Bartfeld S, Clevers H. Tissue-resident adult stem cell populations of rapidly self-renewing organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:656–670. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanpain C, Horsley V, Fuchs E. Epithelial stem cells: turning over new leaves. Cell. 2007;128:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potten CS, Loeffler M. Stem cells: attributes, cycles, spirals, pitfalls and uncertainties. Lessons for and from the crypt. Development. 1990;110:1001–1020. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grapin-Botton A. Ductal cells of the pancreas. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonner-Weir S, Sharma A. Pancreatic stem cells. J Pathol. 2002;197:519–526. doi: 10.1002/path.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finegood DT, Scaglia L, Bonner-Weir S. Dynamics of beta-cell mass in the growing rat pancreas. Estimation with a simple mathematical model. Diabetes. 1995;44:249–256. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Burton FR, Presti ME, et al. Repetitive self-limited acute pancreatitis induces pancreatic fibrogenesis in the mouse. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:665–674. doi: 10.1023/a:1005423122127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo BK, Clevers H. Stem cells marked by the R-spondin receptor LGR5. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:289–302. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Español-Suñer R, Carpentier R, Van Hul N, et al. Liver progenitor cells yield functional hepatocytes in response to chronic liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1564.e1567–1575.e1567. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams MJ, Clouston AD, Forbes SJ. Links between hepatic fibrosis, ductular reaction, and progenitor cell expansion. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:349–356. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker N. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:19–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann W. Regeneration of the gastric mucosa and its glands from stem cells. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:3133–3144. doi: 10.2174/092986708786848587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barker N, van Oudenaarden A, Clevers H. Identifying the stem cell of the intestinal crypt: strategies and pitfalls. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann W. Trefoil factors TFF (trefoil factor family) peptide-triggered signals promoting mucosal restitution. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2932–2938. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5481-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taupin D, Podolsky DK. Trefoil factors: initiators of mucosal healing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrm1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebert MP, Hoffmann J, Haeckel C, et al. Induction of TFF1 gene expression in pancreas overexpressing transforming growth factor alpha. Gut. 1999;45:105–111. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madsen J, Nielsen O, Tornøe I, et al. Tissue localization of human trefoil factors 1, 2, and 3. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:505–513. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7100.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziv O, Glaser B, Dor Y. The plastic pancreas. Dev Cell. 2013;26:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke ZD, Tosh D. Ontogenesis of hepatic and pancreatic stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:586–596. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strobel O, Dor Y, Alsina J, et al. In vivo lineage tracing defines the role of acinar-to-ductal transdifferentiation in inflammatory ductal metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1999–2009. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strobel O, Dor Y, Stirman A, et al. Beta cell transdifferentiation does not contribute to preneoplastic/metaplastic ductal lesions of the pancreas by genetic lineage tracing in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605248104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, et al. Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature. 2004;429:41–46. doi: 10.1038/nature02520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan FC, Bankaitis ED, Boyer D, et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of multipotentiality in Ptf1a-expressing cells during pancreas organogenesis and injury-induced facultative restoration. Development. 2013;140:751–764. doi: 10.1242/dev.090159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rovira M, Scott SG, Liss AS, et al. Isolation and characterization of centroacinar/terminal ductal progenitor cells in adult mouse pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:75–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912589107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopp JL, Dubois CL, Hao E, et al. Progenitor cell domains in the developing and adult pancreas. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1921–1927. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.12.16010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reichert M, Rustgi AK. Pancreatic ductal cells in development, regeneration, and neoplasia. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4572–4578. doi: 10.1172/JCI57131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puri S, Folias AE, Hebrok M. Plasticity and Dedifferentiation within the Pancreas: Development, Homeostasis, and Disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strobel O, Rosow DE, Rakhlin EY, et al. Pancreatic duct glands are distinct ductal compartments that react to chronic injury and mediate Shh-induced metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1166–1177. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baus-Loncar M, Kayademir T, Takaishi S, et al. Trefoil factor family 2 deficiency and immune response. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2947–2955. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrell JJ, Taupin D, Koh TJ, et al. TFF2/SP-deficient mice show decreased gastric proliferation, increased acid secretion, and increased susceptibility to NSAID injury. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:193–204. doi: 10.1172/JCI12529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furukawa T, Duguid WP, Rosenberg L, et al. Long-term culture and immortalization of epithelial cells from normal adult human pancreatic ducts transfected by the E6E7 gene of human papilloma virus 16. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1763–1770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouyang H, Mou L, Luk C, et al. Immortal human pancreatic duct epithelial cell lines with near normal genotype and phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1623–1631. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64800-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longman RJ, Douthwaite J, Sylvester PA, et al. Coordinated localisation of mucins and trefoil peptides in the ulcer associated cell lineage and the gastrointestinal mucosa. Gut. 2000;47:792–800. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.6.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.FitzGerald AJ, Pu M, Marchbank T, et al. Synergistic effects of systemic trefoil factor family 1 (TFF1) peptide and epidermal growth factor in a rat model of colitis. Peptides. 2004;25:793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greeley MA, Van Winkle LS, Edwards PC, et al. Airway trefoil factor expression during naphthalene injury and repair. Toxicol Sci. 2010;113:453–467. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaker A, Rubin DC. Intestinal stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the crypt and stem cell niche. Transl Res. 2010;156:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bickenbach JR. IDENTIFICATION AND BEHAVIOR OF LABEL-RETAINING CELLS IN ORAL-MUCOSA AND SKIN. Journal of Dental Research. 1981;60 doi: 10.1177/002203458106000311011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fendrich V, Esni F, Garay MV, et al. Hedgehog signaling is required for effective regeneration of exocrine pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:621–631. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thayer SP, di Magliano MP, Heiser PW, et al. Hedgehog is an early and late mediator of pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Nature. 2003;425:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nature02009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.