Abstract

BCl3‐induced borylative cyclization of aryl‐alkynes possessing ortho‐EMe (E=S, O) groups represents a simple, metal‐free method for the formation of C3‐borylated benzothiophenes and benzofurans. The dichloro(heteroaryl)borane primary products can be protected to form synthetically ubiquitous pinacol boronate esters or used in situ in Suzuki–Miyaura cross couplings to generate 2,3‐disubstituted heteroarenes from simple alkyne precursors in one pot. In a number of cases alkyne trans‐haloboration occurs alongside, or instead of, borylative cyclization and the factors controlling the reaction outcome are determined.

Keywords: annulation, borylation, cross coupling, electrophilic cyclization, organoboranes

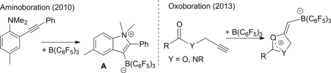

Benzofurans and benzothiophenes are important structures found in pharmaceutical targets (e.g., desketoraloxifene) and organic materials.1, 2 The boronic acid derivatives of these heteroaromatics are desirable as they are bench‐stable, have low toxicity and are effective in many functional group transformations, including the ubiquitous Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling reaction.3 Typically, the formation of these borylated compounds is achieved via the C−H or C−X borylation of the pre‐formed heteroaromatic.3b, 4 An alternative more efficient approach is to form the heteroaromatic scaffold and the C−B bond in one pot via the borylative cyclization of alkynes. This can be mediated by transition metal catalysts5 or in the absence of a metal catalyst by using strong boron electrophiles.6 The latter approach was pioneered using B(C6F5)3 which on addition to appropriately substituted alkynes led to a range of borylated heterocycles, including products derived from aminoboration7 and oxoboration (Scheme 1).8 Other catalyst‐free cyclitive elemento‐borations have been reported, albeit to a lesser extent,5, 6 with reports of cyclitive thioboration particularly rare.9

Scheme 1.

Borylative cyclization of substituted alkynes with B(C6F5)3.

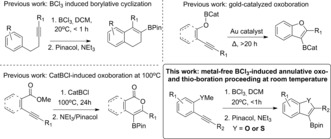

Whilst B(C6F5)3 was crucial in developing metal‐free alkyne borylative cyclization it leads to zwitterionic products such as A (Scheme 1). The use of these species in subsequent functional group transformations is not established, currently limiting their synthetic utility.10 Using alternative boron Lewis acids such as BCl3 to effect borylative cyclization enables the formation of organo‐boronic acid derivatives on work‐up,11 and consequentially access to the myriad of already proven transformations. However, this is an underdeveloped approach with demonstrated, modular protocols scarce. Two notable exceptions are 1) the BCl3‐induced alkyne borylative cyclization where a (hetero)aromatic moiety is the nucleophile attacking the BCl3‐activated alkyne (Scheme 2, top left),12 and 2) the use of B‐chloro‐catecholborane to produce borylated lactones via cyclitive alkyne oxoboration (Scheme 2, bottom left).13 Both protocols generate desirable boronic acid derivatives on (trans)esterification, and are complementary to electrophilic iodinative cyclization (which generates organic electrophiles).14

Scheme 2.

Previous relevant borylative cyclization reactions and this work.

From these studies key requirements enabling borylative cyclization without metal catalysts can be identified, including that the boron electrophile must: a) bind reversibly to the heteroatomic moiety, and b) induce borylative cyclization preferentially to dealkylation reactions (e.g., cyclization occurs prior to O−R cleavage). Guided by these herein we report our studies into the reaction of BCl3 with 2‐alkynyl‐anilines, anisoles and thioanisoles, which led to the development of a simple new route to important boronic acid derivatives of benzothiophenes and benzofurans. This route (Scheme 1, bottom right) is catalyst‐free and thus distinct to a recent cyclitive alkyne oxo‐boration report which required Au catalysts (Scheme 1, top right).15

Our studies commenced by combining equimolar BCl3 and N,N‐dimethyl‐2‐(phenylethynyl)aniline (1) for comparison with B(C6F5)3 which formed zwitterion A.7 In contrast to B(C6F5)3 addition of BCl3 did not lead to a borylated indole with X‐ray diffraction studies revealing it had instead formed 2 (Figure 1), the product from alkyne trans‐haloboration. The reactivity disparity between BCl3 and B(C6F5)3 is attributed to stronger N→B coordination with BCl3 due to the lower steric crowding around boron. Notably, 2 is not the expected product from the direct haloboration of an alkyne with BCl3, which would proceed by syn‐addition of Cl2B−Cl,16 suggesting 2 is formed by a different mechanism. Precedence for alkyne trans‐haloboration is extremely limited, with compound C (Figure 1), the trans‐haloboration/demethylation product from the addition of BBr3 to o‐alkynyl‐anisole B a notable exception.17 With direct haloboration precluded it is possible that the reaction proceeds from the (N,N‐Me2‐aniline)–BCl3 adduct by chloride transfer from boron to carbon, related to that calculated for intramolecular alkyne trans‐hydroboration.18

Figure 1.

Trans‐haloboration of 1 with BCl3. Top right, solid state structure of 2, thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability and hydrogens omitted for clarity. Bottom, a previously reported alkyne trans‐haloboration.

With the formation of C3‐borylated indoles disfavored under these conditions due to trans‐haloboration the propensity of o‐alkynyl anisoles to undergo borylative cyclization was explored. The rapid formation of C from B clearly indicates that trans‐haloboration also is viable with o‐alkynyl‐anisoles, however, this reaction was proposed to proceed via initial ether demethylation then haloboration.17 While ether cleavage of anisoles with BBr3 is well documented, detailed studies into the mechanism are rare,19 but one recent report calculated that PhO−Me cleavage is a bimolecular process involving two Me(Ph)O−BBr3 moieties.19a Thus B may be prearranged to undergo rapid ether cleavage and other o‐alkynyl anisoles may be less prone to ether cleavage, particularly using BCl3 instead of BBr3. Consistent with this the combination of equimolar anisole and BCl3 in DCM at 20 °C resulted in the formation of a single 11B resonance at 32 ppm with minimal ether cleavage observed even after 30 h at 20 °C (only ca. 2.5 % CH3Cl was formed by 1H NMR spectroscopy). The 32 ppm 11B chemical shift is consistent with an equilibrium between the Lewis adduct and free BCl3 and anisole. Thus anisole binding to BCl3 is reversible and ether cleavage is not significant at 20 °C, suggesting that alkyne borylative cyclization using BCl3 is viable.

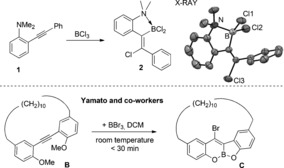

1‐Methoxy‐2‐(phenylethynyl)benzene (3 a) was cyclized in DCM using BCl3 (Scheme 3). The reaction was rapid (<5 min at 20 °C), as indicated by the consumption of 3 a along with the generation of CH3Cl (δ 1H 3.02 ppm) and a new major resonance centered at 51 ppm in the 11B NMR spectrum, consistent with a heteroaryl‐BCl2 species. A minor broad resonance at 14.2 ppm in the 11B NMR spectrum was also observed. Esterification with pinacol/NEt3 enabled the isolation of 4 a in 56 % yield without column chromatography. No intermediates are observed so detailed discussion of the mechanism is not warranted, although alkyne activation by BCl3 and cyclization presumably occurs prior to demethylation based on the slow ether cleavage observed on combining anisole and BCl3. It is noteworthy that a non‐linked analogue of B, 1,2‐bis(2‐methoxyphenyl)ethyne, undergoes rapid trans‐haloboration and demethylation with both BCl3 and BBr3, thus the reactivity disparity between 3 a and B is not due to the use of different boron trihalides.

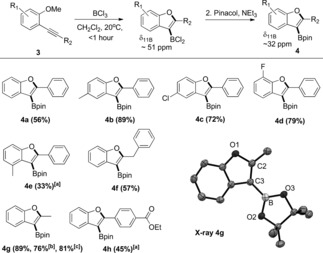

Scheme 3.

BCl3‐induced borylative cyclization of 2‐alkynyl‐anisoles. Bottom right, solid state structure of 4 g, thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability and hydrogens omitted for clarity. [a] 12 h. [b] 6 mmol scale to produce 1.16 g of 4 g. [c] Using non‐purified solvents under ambient atmosphere.

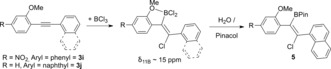

Exploration of the substrate scope revealed that electron‐donating and ‐withdrawing groups on the anisole ring are compatible in certain positions (4 b–e). Furthermore, borylative cyclization is not limited to diarylalkynes with benzyl‐ and methyl‐substituted alkynes converted to the benzofurans 4 f and 4 g in good yield, with the structure of 4 g confirmed by X‐ray crystallography. 4 g was also accessible on a gram scale and using non‐purified solvents under ambient conditions in good yield. Whilst a phenyl group substituted with an electron‐withdrawing group para to the alkyne led to the borylated benzofuran in moderate isolated yield (4 h), when ester and nitro groups were incorporated into the anisole ring para to the alkyne this led to low conversions to the benzofuran‐BCl2 species (the δ 11B 51 ppm is the minor component). Instead a δ 11B 15 ppm resonance was the major product with 3 i (Scheme 4), whilst for 3 j (Scheme 4), where a naphthyl group has been incorporated resulting in an increase in the steric environment around the alkyne, the major δ 11B resonance is centered at 14 ppm. With both these substrates after the addition of BCl3 the 1H NMR spectra revealed that minimal CH3Cl had formed (consistent with δ 11B 51 ppm being a minor resonance). Instead a singlet was observed at 4.56 and 4.49 ppm, respectively from 3 i and 3 j, more consistent with an intact ArylOMe unit coordinated to a Lewis acid. Attempts to isolate the product derived from 3 i after esterification with Et3N/pinacol led to isolation of the starting alkyne, presumably due to E2 elimination. The naphthyl derivative 5 was formed as the major product post esterification, with 1H, 13C{1H}, 11B NMR spectroscopy fully consistent with haloboration, a formulation supported by mass spectroscopy. Therefore to form borylated benzofurans in acceptable isolated yields by BCl3‐induced borylative cyclization significant bulk around the alkyne and strong EWG in the para position (to the alkyne) of the anisole moiety have to be avoided.

Scheme 4.

Trans‐haloboration with strong electron‐withdrawing/bulky groups.

With the substituent effects probed the functional group tolerance of BCl3‐induced borylative cyclization was further explored using the “robustness screen” methodology;20 specifically, monitoring the cyclization of 3 b in the presence of various additives. This revealed that borylative cyclization was not affected by additives containing nitro, vinyl or CF3 groups (in each case >80 % of the borylated benzofuran was formed with the additive not consumed). However, benzaldehyde and acetone were not compatible, with the addition of BCl3 to separate reactions containing these additives and 3 b leading to additive consumption and significantly reduced benzofuran formation. Other Lewis basic groups were compatible with borylative cyclization provided that >2 equivalents of BCl3 was used, with the first equivalent of BCl3 coordinating to the Lewis basic group (in each case >70 % conversion to the borylated benzofuran was observed in the presence of a tertiary amine, a tertiary amide, a pyridine and a nitrile). Established routes to 3‐borylated‐2‐organo‐benzofurans generally proceed from 3‐halo‐2‐organo‐benzofurans by metallation/quenching with B(OR)3, or by Pd‐catalyzed Miyaura borylation.3b Notably these routes are not compatible with some of the functional groups tolerated by BCl3‐induced borylative cyclization (e.g., amide/nitrile groups are generally incompatible with metallation). Furthermore, this methodology is complementary to iridium‐catalyzed C−H borylation which provides C2‐ or C7‐borylated benzofurans.4 Finally, it worth emphasizing that 4 a–h are formed at ambient temperature without a catalyst using inexpensive BCl3, in contrast the previous borylative cyclization route to C3‐borylated benzofurans required pre‐installation of the borane (using NaH/CatBCl), Au catalysis, raised temperatures and ≥20 h.15

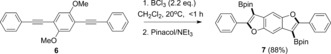

Multiple borylative cyclizations also proceed with appropriately substituted diynes, with 6 converted to 7, a diborylated diaryl‐benzo[1,2‐b:4,5‐b′]difuran, in excellent yield using BCl3 (Scheme 5). 7 represents a versatile precursor to 2,3,6,7‐tetraarylbenzo[1,2‐b:4,5‐b′]difurans which are of interest as hole transport materials.2 To the best of our knowledge 3,7‐diborylated benzodifurans have not been previously reported.

Scheme 5.

Double BCl3‐induced borylative cyclization.

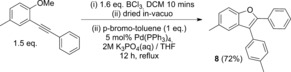

While the purified borylated benzofurans reported herein are effective in Suzuki–Miyaura cross couplings (e.g., 4 g with 4‐bromo‐toluene) to enhance the utility of this methodology a one‐pot borylative cyclization/Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling procedure was developed (Scheme 6). This does not require isolation of the borylated benzofuran, instead the benzofuran‐BCl2 product is hydrolyzed in situ to the boronic acid and then subjected to conventional Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling conditions. This one‐pot procedure is a simple and rapid way to generate 2,3‐disubstituted benzofurans from simple alkynyl precursors in good yield (72 % isolated yield of 8).

Scheme 6.

One pot borylative cyclization and Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling.

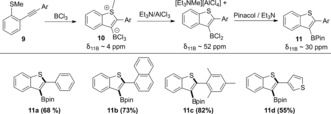

o‐Alkynyl‐thioanisoles and BCl3 were explored next to assess if BCl3 induced borylative cyclization was possible via alkyne thio‐boration. Firstly, equimolar thioanisole and BCl3 were combined which led to a species with δ 11B 7.9 ppm, indicating significant adduct formation, but importantly no S−Me cleavage was observed. Furthermore, previous work has shown that thioanisole‐(BHxCl3−x) (x=1 or 2) compounds are effective hydroborating agents at 20 °C indicating that an electrophilic borane is accessible from these Lewis adducts.21 Therefore BCl3 was added to methyl(2‐(phenylethynyl)‐phenyl)sulfane (9 a) in DCM with in situ 11B NMR spectroscopy revealing one major product had formed with a broad resonance centered at 4 ppm, which does not correspond to a 3‐BCl2‐benzothiophene species (expected δ 11B ca. 52 ppm).22 This is consistent with no chloromethane being observed in the 1H NMR spectrum. Methylsulfonium cations are significantly weaker methylating agents (less prone to Me+ transfer to nucleophiles) than methyloxonium cations,23 therefore we surmised that the major compound is the zwitterion 10 a analogous to A (Scheme 7). In our hands crystalline material of 10 could not be isolated therefore support for this assignment was provided by combining 9 a with BCl3 (to form 10 a) and then adding Et3N as a stronger nucleophile to induce demethylation. This led to formation of [Et3NMe]+ (by 1H NMR spectroscopy) and a new major broad 11B resonance at 6.3 ppm attributed to the product from demethylation of 10 a by Et3N. On addition of one equivalent of AlCl3 this compound was then converted to a new major species displaying a broad 11B resonance at 52.9 ppm fully consistent with a benzothiophene‐BCl2 compound.22 The same boron species is formed by initial addition of AlCl3 to 10 a followed by Et3N. Esterification of the δ 11B 52.9 ppm species with excess pinacol/Et3N led to the desired product 11 a in good isolated yield (68 %), unequivocally confirming that borylative cyclization has taken place. This reaction is notable as a rare example of cyclitive alkyne thioboration.9c It should be noted that attempts to directly esterify the zwitterion 10 a led to significantly lower isolated yields of 11 a (38 %). This is attributed to 10 a having a greater propensity to undergo protodeboronation due to the more nucleophilic anionic benzothienyl‐BCl3 moiety (relative to benzothienyl‐BCl2).

Scheme 7.

Borylative cyclization followed by demethylation/dehalogenation to form benzothienyl‐BCl2 and then subsequent esterification.

With the functional group tolerance already assessed in benzofuran formation other thioanisole substrates were selected to assess if alkyne haloboration was a competitive pathway. As there was no evidence (in situ or post work‐up) for haloboration with 9 a bulkier substituents, naphthyl and mesityl, 9 b and 9 c, respectively, were incorporated into the alkyne. Addition of BCl3 to these alkynes resulted in similar outcomes to that observed with 9 a with no evidence for haloboration in either case, suggesting it is not a competitive reaction with thioanisoles. Again, the isolated yield of the benzothiophene pinacol boronate ester is higher on addition of Et3N/AlCl3 prior to esterification (e.g., for producing 11 b yield=48 % direct from the zwitterion 10 b whereas it is 73 % on esterification after addition of Et3N/AlCl3). To demonstrate further that this methodology allows access to otherwise challenging to synthesize boronic acid derivatives 11 d was produced in 55 % isolated yield. Compound 11 d is not readily accessible by established borylation routes commencing from 2‐(thiophen‐3‐yl)benzo[b]thiophene (e.g., Ir‐catalyzed borylation and halogenation/lithiation approaches would all proceed at the thienyl alpha position).3b, 4

In conclusion, two distinct reaction pathways operate on addition of BCl3 to arylalkynes possessing ortho E−Me (E=NMe, O or S) moieties, specifically borylative cyclization and trans‐haloboration. The latter occurs with N,N‐dimethyl‐2‐(phenylethynyl)aniline whilst all the o‐alkynyl‐thioanisoles studied react selectively by borylative cyclization. For o‐alkynyl‐anisoles both pathways are observed, with borylative cyclization dominating provided strong electron‐withdrawing groups on the anisole moiety para to the alkyne, or significant steric bulk are absent. This methodology is a simple, scalable and metal‐free route to useful benzofuran and benzothiophene boronic acid derivatives, many of which would be challenging to access by other established borylation methodologies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the ERC under framework 7 (Grant number 305868), and the Royal Society (M.J.I.) for financial support. We also acknowledge the EPSRC (grant number EP/K039547/1) for financial support. Additional research data supporting this publication are available as Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

A. J. Warner, A. Churn, J. S. McGough, M. J. Ingleson, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 354.

References

- 1.2,3-substituted benzofurans and benzothiophenes are privileged structures e.g., in desketoraloxifene:

- 1a. Radadiya A., Shah A., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 356; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Cho C.-H., Jung D.-I., Neuenswander B., Larock R. C., ACS Comb. Sci. 2011, 13, 501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For an example of a materials application see: Tsuji H., Mitsui C., Ilies L., Sato Y., Nakamura E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 11902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Miyaura N., Suzuki A., Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 2457; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Boronic Acids: Preparation and Applications (Ed.: D. Hall), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2011; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Schneider N., Lowe D. M., Sayle R. A., Tarselli M. A., Landrum G. A., J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mkhalid I. A. I., Barnard J. H., Marder T. B., Murphy J. M., Hartwig J. F., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For a review see:

- 5a.E. Buñuel, D. J. Cárdenas, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 10.1002/ejoc.201600697; For a particularly relevant recent example see:

- 5b. Huang J., Macdonald S. J. F., Harrity J. P. A., Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 8770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Melen R. L., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For a key early publication see: Voss T., Chen C., Kehr G., Nauha E., Erker G., Stephan D. W., Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For a key initial publication see:

- 8a. Melen R. L., Hansmann M. M., Lough A. J., Hashmi A. S. K., Stephan D. W., Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 11928; For more recent work see (and references therein): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Wilkins L. C., Lawson J. R., Wieneke P., Rominger F., Hashmi A. S. K., Hansmann M. M., Melen R. L., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 14618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For rare examples of metal-free alkyne cyclitive thioboration:

- 9a. Tanur C. A., Stephan D. W., Organometallics 2011, 30, 3652; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Eller C., Kehr G., Daniliuc C. G., Fröhlich R., Erker G., Organometallics 2013, 32, 384; During the reviewing of this manuscript the following alkyne cyclitive thioboration process was reported: [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Faizi D. J., Davis A. J., Meany F. B., Blum S. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.To our knowledge [ArylB(C6F5)3]− species have not been utilised in Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling, although ArylB(C6F5)2 species have been, for a recent example see: Eller C., Kehr G., Daniliuc C. G., Stephan D. W., Erker G., Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 7226. [Google Scholar]

- 11.For a recent example see: Yang C.-H., Zhang Y.-S., Fan W.-W., Liu G.-Q., Li Y.-M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12636; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 12827. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Warner A. J., Lawson J. R., Fasano V., Ingleson M. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 11245; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 11397. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Faizi D. J., Issaian A., Davis A. J., Blum S. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For cyclization using Group 16 and 17 electrophiles see (and references therein): Mehta S., Waldo J. P., Larock R. C., J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hirner J. J., Faizi D. J., Blum S. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Excluding acetylene cis-haloboration dominates on combining alkynes and BX3: Lappert M., Prokai B., J. Organomet. Chem. 1964, 1, 384. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Uchikawa Y., Tazoe K., Tanaka S., Feng X., Matsumoto T., Tanaka J., Yamato T., Can. J. Chem. 2012, 90, 441. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yuan K., Suzuki N., Mellerup S. K., Wang X., Yamaguchi S., Wang S., Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Sousa C., Silva P. J., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5195; [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Kosak T. M., Conrad H. A., Korich A. L., Lord R. L., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 7460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Collins K. D., Glorius F., Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zaidlewicz M., Kanth J. V. B., Brown H. C., J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 6697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bagutski V., Del Grosso A., Ayuso Carrillo J., Cade I. A., Helm M. D., Lawson J. R., Singleton P. J., Solomon S. A., Marcelli T., Ingleson M. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Downie I. M., Heaney H., Kemp G., King D., Wosley M., Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 4005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary