Abstract

One molecular‐based approach that increases potency and reduces dose‐limited sequela is the implementation of selective ‘targeted’ delivery strategies for conventional small molecular weight chemotherapeutic agents. Descriptions of the molecular design and organic chemistry reactions that are applicable for synthesis of covalent gemcitabine‐monophosphate immunochemotherapeutics have to date not been reported. The covalent immunopharmaceutical, gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was synthesized by reacting gemcitabine with a carbodiimide reagent to form a gemcitabine carbodiimide phosphate ester intermediate which was subsequently reacted with imidazole to create amine‐reactive gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphorylimidazolide) intermediate. Monoclonal anti‐IGF‐1R immunoglobulin was combined with gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphorylimidazolide) resulting in the synthetic formation of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R]. The gemcitabine molar incorporation index for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐R1] was 2.67:1. Cytotoxicity Analysis – dramatic increases in antineoplastic cytotoxicity were observed at and between the gemcitabine‐equivalent concentrations of 10−9 M and 10−7 M where lethal cancer cell death increased from 0.0% to a 93.1% maximum (100.% to 6.93% residual survival), respectively. Advantages of the organic chemistry reactions in the multistage synthesis scheme for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] include their capacity to achieve high chemotherapeutic molar incorporation ratios; option of producing an amine‐reactive chemotherapeutic intermediate that can be preserved for future synthesis applications; and non‐dedicated organic chemistry reaction scheme that allows substitutions of either or both therapeutic moieties, and molecular delivery platforms.

Keywords: antineoplastic cytotoxic potency, covalent immunochemotherapeutic, gemcitabine, IGF‐1R, margin‐of‐safety, selective ‘targeted’ delivery, synergistic efficacy, synthesis

Many conventional chemotherapeutics are capable of effectively resolving B‐CLL, but dose‐limiting sequelae often compromise attaining this treatment objective. In field of clinical oncology, gemcitabine is primarily administered for the therapeutic management of various carcinomas including non‐small cell pulmonary carcinoma,1, 2, 3 pancreatic carcinoma,4, 5, 6 renal carcinoma,7 urinary bladder carcinoma,8, 9 breast cancer,10, 11, 12 prostatic carcinoma,13 and ovarian carcinoma,14, 15 while preliminary investigations indicated it may also be beneficial for the therapeutic management of esophageal cancer and leukemia/lymphoma.16, 17, 18 Gemcitabine in dual combination with fludarabine exerts synergistic antineoplastic properties.18 The plasma half‐life for gemcitabine is brief, which is in part due to it being rapidly deaminated resulting in the rapid excretion of the inactive metabolite into the urine.19, 20, 21 Adverse haematological effects are some of the most common sequelae associated with gemcitabine administration with neutropenia having the highest case frequency (≤90%). Functioning as an antimetabolite class chemotherapeutic, gemcitabine (dFdc ‐or‐ 2,2‐difluoro‐2‐deoxycytidine; 2,2‐difluorodeoxyribofuranosylcytosine; dFdC) is a deoxycytidine analog that is transformed into a triphosphorylated nucleotide ‘decoy’ that in turn replaces or substitutes for cytidine during DNA replication. A second mechanism of action responsible for the biological effect of gemcitabine is an inhibition and inactivation of ribonucleotide reductase biochemical activity resulting in an inability to synthesize deoxyribonucleotides necessary for DNA replication and repair. The ultimate biological effect of gemcitabine interference with DNA replication is the initiation of apoptosis.

Objectives directed toward developing alternatives to conventional small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutics have motivated the identification of trophic receptors and cell‐differentiating antigens that are overexpressed on the exterior surface membrane by neoplastic cell populations that regulate their vitality and growth rate. Surface membrane CD19,22 CD20,23, 24 CD30,22 CD52,25, 26, 27 and IGF‐1R28 are a few of the antigenic sites that are uniquely or highly overexpressed in conditions of leukemia and lymphoma such as B‐cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B‐CLL). Similarly, many adenocarcinoma and carcinoma affecting the breast, prostate, intestine, ovary, or kidney overexpress the endogenous trophic receptors, EGFR, HER2/neu, IGF‐1R, and VEGFR on their exterior surface membranes. Monoclonal IgG binding at these sites can serve as a molecular strategy for suppressing the biological integrity and function of neoplastic cell populations.29 Most notable in this regard is neoplastic cell viability,30, 31 proliferation rate,31, 32 local invasiveness,33 metastatic potential,34, 35 and chemotherapeutic resistance (e.g., P‐glycoprotein co‐expression).33, 36, 37

Endogenous trophic receptors or cell‐differentiating antigens that are uniquely or highly overexpressed on the exterior surface membrane of neoplastic populations can also be utilized to facilitate the selective ‘targeted’ delivery of chemotherapeutic moieties. Synthesis of covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutic provides the advantage of being able to facilitate and induce increased levels of chemotherapeutic moiety deposition within the cytosol environment of neoplastic cells. Such a process is facilitated by selective ‘targeted’ delivery38 where a gemcitabine moiety of the covalent immunochemotherapeutic becomes an apparently a poor substrate for MDR‐1 (multidrug resistance efflux pump)39 and presumably for the rapidly deaminating enzymes, cytidine deaminase, or, after phosphorylation, deoxycytidylate deaminase. In contrast to covalent anthracycline immunochemotherapeutics, a very limited number of published research investigations have described the molecular design, synthesis, and antineoplastic cytotoxic activity of covalent gemcitabine‐ligand preparations and an even fewer number of reports have described production and evaluation of gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics.

Covalent immunochemotherapeutics that possess properties of selective ‘targeted’ delivery have traditionally been synthesized utilizing the anthracyclines38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 where doxorubicin65, 66, 67, 68, 69 has been most commonly been utilized in this capacity while daunorubicin70, 71, 72 and epirubicin38, 64, 73, 74 have also be employed but less frequently. Organic chemistry reactions for covalently bonding gemcitabine chemotherapeutic to a biologically relevant peptide sequences or large molecular weight proteins have rarely been described.75, 76, 77 Covalent biopharmaceuticals that possess properties of selective ‘targeted’ delivery most commonly utilize monoclonal IgG or fragments of IgG (e.g., F(ab’)2 or Fab’), and less frequently receptor ligands, peptide fragments of receptor ligands, or synthetic ligands that recognize and physically bind to receptor complexes or unique antigenic sites expressed on the exterior surface membrane of cell populations.38, 64, 67, 68, 75, 78 Despite rather extensive familiarity with the biological effect of anti‐HER2/neu and anti‐EGFR on the vitality of cancer cell populations and its application in clinical oncology, there has correspondingly been surprisingly little research devoted to the molecular design, organic chemistry synthesis, and potency evaluation of covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics.75, 76, 77 Given this perspective, the molecular design and a series of organic chemistry reactions are described that can be implemented in a multistage regimen for synthesizing a covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic. The optimized organic chemistry reaction regimens are more expedient (rapid) and convenient, which accounts for their high degree of flexibility that affords their application for the synthetic production of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] and other analogous covalent immunochemotherapeutic agents. The organic chemistry reaction regimens as described from a methodology perspective are similar to those illustrated in previous research investigations that for the first time delineated two different and separate organic chemistry reaction regimens for the synthesis of covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics.75, 76 The organic chemistry reaction scheme utilized to synthesize covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic was founded on organic chemistry reaction regimens initially employed in synthesis regimens for the synthetic production of fludarabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R]79 and dexamethasone‐(C21‐ phosphoramide)‐[anti‐EGFR]. The selection of anti‐IGF‐1R immunoglobulin for the synthesis of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was based on the known overexpression of both IGF‐1R and EGFR by the human pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) and the dual sensitivity of this particular neoplastic cell type to both corticosteroids like dexamethasone and cortisol, in addition to many conventional small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutics.

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutic synthesis

Stage‐I: synthesis format for amine‐reactive chemotherapeutic intermediates:

Gemcitabine‐5′‐methyl‐dihydrogen monophosphate was formulated at a concentration of 3.85 × 10−2 m in modified PBS buffer (phosphate 5.0 mm, NaCl 75 mm, EDTA 5.0 mm, pH 7.4) and reacted with 1‐ethyl‐3‐[3‐dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide at a 5:1 molar ratio. The Stage‐I and Stage‐II reaction mixture was then allowed to gently stir at 25 °C for 10 to 15 min.

Stages‐II and III: synthesis format for covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics utilizing an amine‐reactive chemotherapeutic intermediate:

Monoclonal IgG fractions of anti‐IGF‐1R (3.0 mg, 2.0 × 10−5 mmol: R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) devoid of molecular stabilizing agents and formulated in imidazole buffer (100 mm, pH 6.0) was combined at a 1:50 molar ratio with the amine‐reactive gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphorylimidazolide) intermediate generated as the end product from the Stage‐I synthesis reaction scheme. The Stage‐II reaction mixture was then gently stirred continuously for 2 h at 25 °C to maximize the synthesis yield of the Stage‐III covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic end product. Residual unreacted gemcitabine‐(5′‐methyl‐dihydrogen‐monophosphate) was removed from the covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic by serial microfiltration (MWCO = 10‐kDa) and buffer exchange utilizing conventional PBS (phosphate 100 m, NaCl 150 m, pH 7.4). Note: The murine monoclonal anti‐human IGF‐I R detects less than 0.15% cross‐reactivity or interference from recombinant human (rh) IGF‐I, rhIGF‐II, rhIL‐3 R α, rhIL‐9 R, and rhTGF‐β RII. Binding avidity for anti‐IGF‐1R is approximately Ka = 6.6 to 10 × 105/mol.

1.2. Molecular analysis and characterization of properties

1.2.1. Relative non‐covalently bound gemcitabine content

Detection of the relative amount of residual non‐covalently bound gemcitabine contained in the covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic Stage‐III reaction end product was determined by analytical format high‐performance thin‐layer chromatography (HP‐TLC silica gel, 250 μm thickness, UV 254 nm indicator). Protein binding of gemcitabine to albumin in plasma is negligible (<5%) and substantially lower for purified immunoglobulin, which is complemented by the highly efficient elution and extraction of gemcitabine with a wide range of acidified mixed organic and aqueous liquid‐phase systems.80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85 Sensitivity of detecting residual unreacted gemcitabine by analytical HP‐TLC following exhaustive removal by serial microfiltration was enhanced by evaluating highly concentrated formulations of the Stage‐III gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] end product and the application of standardized gemcitabine reference controls formulated at matched reference control concentrations. Individual silica gel HP‐TLC plates were subsequently developed utilizing a mobile‐phase solvent system composed of propanol/ethanol/ddH20 (17:5:5 v/v ratio). Detection of residual unreacted gemcitabine in gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] and standardized gemcitabine reference controls following analytical HP‐TLC development was subsequently determined by direct UV illumination. The total gemcitabine concentration within synthesized gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] formulations following exhaustive serial microfiltration was equal to or greater than 10−4 m, which is well within the range of detection for gemcitabine86 and analogous chemotherapeutic agents87, 88 by analytical scale HP‐TLC analysis. Complementary methods involve combining the covalent immunochemotherapeutic 1:5 v/v with cold methanol or cold chloroform:isopropanol (2:1 v/v) and measurement of free non‐covalently bound chemotherapeutic in the resulting supernatant.

1.2.2. Measurement of covalently bound gemcitabine

Total individual absorbance levels for gemcitabine‐5’methyl‐dihydrogen‐monophosphate, immunoglobulin, and immunoglobulin in combination with gemcitabine‐5’‐methyl‐dihydrogen‐monophosphate standardized reference controls in addition to gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] were measured at 235 nm. Concentrations of the immunoglobulin component contained within the Stage‐III gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] end product and IgG standardized reference controls were measured at 660 nm utilizing a metal‐dye complex reagent (660‐nm Protein Assay, Pierce Thermo Scientific). Concentration of the IgG component within the Stage‐III end product determined by measurements at 660 nm was then utilized to calculate the corresponding absorbance measured at 235 nm. Differences between the absorbance for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramide)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] measured at 235 nm and the calculated 235‐nm absorbance for the immunoglobulin content of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] were then utilized to determine the total gemcitabine‐equivalent concentration within the Stage‐III covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic end product.

1.2.3. Mass‐separation analysis for detection of polymerization and fragmentation

Covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic in addition to reference control anti‐IGF‐1R immunoglobulin fractions formulated at a standardized protein concentration of 60 μg/mL was combined 50/50 v/v with conventional SDS‐PAGE sample preparation buffer (Tris/glycerol/bromophenol blue/SDS) without 2‐mercaptoethanol or boiling. Covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic, reference control IgG (0.9 μg/well), and a mixture of prestained molecular weight marker reference controls were then individually developed by non‐reducing SDS‐PAGE (11% acrylamide) performed at constant power of 100 V 2.5 h at 3 °C.

1.2.4. Detection analyses for polymerization and fragmentation

Covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic following mass/size‐dependent separation by non‐reducing SDS‐PAGE was equilibrated in tank buffer devoid of methanol. Mass/size‐separated gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic contained within acrylamide SDS‐PAGE gels was then transferred laterally onto sheets of nitrocellulose membrane at 20 volts (constant voltage) for 16 h at 2° to 3 °C with the transfer manifold packed in crushed ice.

Covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic laterally transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane was then equilibrated in Tris‐buffered saline (TBS: Tris‐HCl 0.1 m, NaCl 150 mm, pH 7.5, 40 mL) at 4 °C for 15 min followed by an incubation period at 2° to 3 °C for 16 h in TBS blocking buffer (Tris 0.1 m, pH 7.4, 40 mL) containing bovine serum albumin (5%) applied in combination with gentle horizontal agitation. Prior to further processing, nitrocellulose membranes were vigorously rinsed in Tris‐buffered saline (Tris 0.1 m, pH 7.4, 40 mL, n = 3).

Rinsed BSA‐blocked nitrocellulose membranes developed for ligand‐blot detection analyses were incubated with HRPO‐Protein G conjugate (0.25 μg/mL) at 4 °C for 18 h on a horizontal orbital shaker. Nitrocellulose membranes following vigorously rinsing in TBS (pH 7.4, 4 °C, 50 mL, n = 3) were incubated in blocking buffer (Tris 0.1 m, pH 7.4, with BSA 5%, 40 mL). Blocking buffer was decanted from nitrocellulose membrane blots, which were again vigorously rinsed in TBS (pH 7.4, 4 °C, 50 mL, n = 3) before incubation with HRPO chemiluminescent substrate (25 °C; 5–10 min). Under dark conditions, chemiluminescent autoradiography images were acquired by exposing radiographic film (Kodak BioMax XAR, Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) to nitrocellulose membranes sealed within transparent ultraclear resealable plastic envelopes.

1.3. Gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] antineoplastic cytotoxic potency

1.3.1. Multidrug‐resistant pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell culture

The multidrug‐resistant human pulmonary adenocarcinoma/alveolar basal epithelial cell line (A549 derived in 1972 from a 58‐year‐old Caucasian male) was utilized as an ex vivo model for neoplastic disease. Characteristic features and biological properties of the pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) cell line include chemotherapeutic resistance and overexpression of membrane endogenous trophic receptors or antigens including (i) epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (EGFR, ErbB1, HER1: 170–180 kDa); (ii) HER2/neu (EGFR2, ERBB2, CD340, HER2, MLN19, Neu, NGL, TKR1); (iii) insulin‐like growth factor receptor type 1 (IGF‐1R, CD221, IGFIR, IGFR, JTK13, 320‐kDa); (iv) interleukin‐7 receptor (IL‐7 R); (v) β1‐integrin (CD29, ITGB1, FNRB, GPIIA, MDF2, MSK12, VLA‐BETA, VLAB, 110–130 kDa); and (iv) folate receptors (FR, 100‐kDa). The EGFR trophic membrane receptor is also overexpressed in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) at a frequency of 40% to 80% and most commonly in squamous cell and bronchoalveolar carcinoma subtypes.89 Other neoplastic cells that overexpress EGFR include Chinese hamster ovary cell (CHO = 1.01 × 105 EGFR/cell), gliomas (2.7 to 6.8 × 105 EGFR/cell), epidermoid carcinoma (A431 = 2.7 × 106/cell), and malignant glioma (U87MG = 5.0 × 105/cell).

Pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) populations were propagated until monolayers were ≥85% confluent in 150‐cc2 tissue culture flasks containing F‐12K growth media supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10% v/v) and penicillin–streptomycin at a temperature of 37 °C under a gas atmosphere of carbon dioxide (5% CO2) and air (95%). Trypsin or any other biochemically active enzyme fractions were not used to facilitate harvest of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) cell suspensions for seeding of tissue culture flasks or multiwell tissue culture plates. Growth media were not supplemented with growth factors, growth hormones, or any other type of growth stimulant.

1.3.2. Cell‐ELISA detection of total external membrane‐bound IgG‐Immunoglobulin

Pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) cell suspensions were seeded into 96‐well microtiter plates in aliquots of 2 × 105 cells/well and allowed to form a confluent adherent monolayer over a period of 24 to 48 h. The growth media content in each individual well was removed manually by pipette, and the cellular monolayers were then serially rinsed (n = 3) with PBS followed by their stabilization onto the plastic surface of 96‐well microtiter plates with paraformaldehyde (0.4% in PBS, 15 min). Stabilized cellular monolayers were then incubated in triplicate with gradient concentrations of covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic formulated at immunoglobulin‐equivalent concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, and 1.0 μg/mL in tissue culture growth media (200 μL/well). Direct contact incubation between pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) cellular monolayers and gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was performed at 37 °C over a 3‐hour incubation period under a gas atmosphere of carbon dioxide (5% CO2) and air (95%). Following serial rinsing with PBS (n = 3), development of stabilized pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) monolayers entailed incubation with β‐galactosidase‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse IgG (1:500 dilution) for 2 h at 25 °C with residual unbound IgG removed by serial rinsing with PBS (n = 3). Final development of the cell‐ELISA required serial rinsing (n = 3) of stabilized pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) monolayers with PBS followed by incubation with nitrophenyl β‐D‐galactopyranoside substrate (100 μL/well of ONPG formulated fresh at 0.9 mg/mL in PBS pH 7.2 containing MgCl2 10 mm, and 2‐mercaptoethanol 0.1 m). Absorbance within each individual well was measured at 410 nm (630 nm reference wavelength) after incubation at 37 °C for a period of 15 min.

1.3.3. Cell vitality stain‐based assay for measuring cytotoxic antineoplastic potency

Individual preparations of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] were formulated in growth media at final standardized gemcitabine‐equivalent concentrations of 10−9, 10−8, 10−7, 10−6, and 10−5 m. Each standardized gemcitabine‐equivalent concentration of the covalent immunochemotherapeutics was then transferred in triplicate into 96‐well microtiter plates containing pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) monolayers and growth media (200 μL/well). Covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic was then incubated in direct contact with pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) monolayer populations for a period of 192 h at 37 °C under a gas atmosphere of carbon dioxide (CO2 5%) and air (95%). Following the initial 96‐hour incubation period, and then again at 144‐hour postinitial challenge, pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) populations were replenished with fresh tissue culture media with or without covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic.

Antineoplastic cytotoxic potency of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was measured by removing all contents within the 96‐well microtiter plates manually by pipette followed by serial rinsing of stabilized monolayers (n = 3) with PBS followed by incubation with 3‐[4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl]‐2,5‐diphenyl tetrazolium bromide vitality stain reagent formulated in RPMI‐1640 growth media devoid of pH indicator or bovine fetal calf serum (MTT: 5 mg/mL). During an incubation period of 3–4 h at 37 °C under a gas atmosphere of carbon dioxide (5% CO2) and air (95%), the enzyme mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase was allowed to convert the MTT vitality stain reagent to navy‐blue formazone crystals within the cytosol of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) cell populations (some reports suggest that NADH/NADPH‐dependent cellular oxidoreductase enzymes may also be involved in the biochemical conversion process). Contents were then removed from each of the 96 wells in the microtiter plate, followed by serial rinsing with PBS (n = 3). The resulting blue intracellular formazone crystals were dissolved with DMSO (300 μL/well) and then spectrophotometric absorbance of the resulting blue‐colored supernatant measured at 570 nm using a computer‐integrated microtiter plate reader.

2. Results

2.1. Covalently bound gemcitabine content

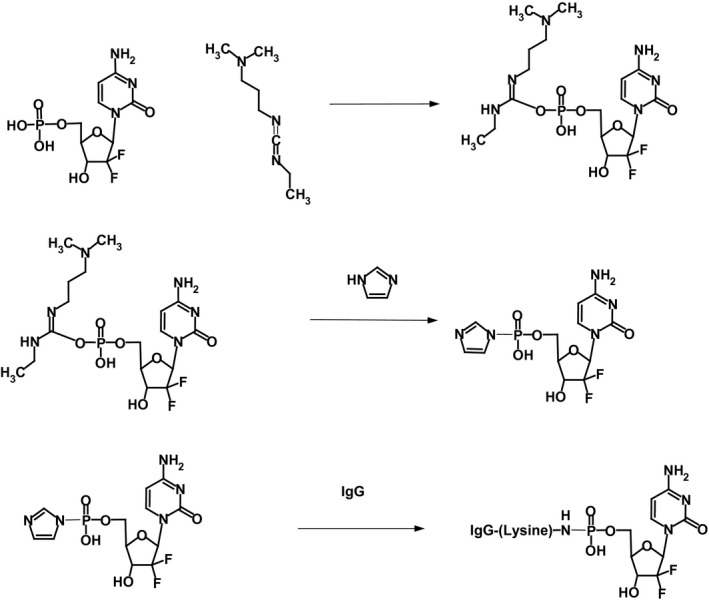

The Stage‐I end product in PBS at pH 7.4 following exclusive reaction of 1‐ethyl‐3‐[3‐dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide (Ib) with gemcitabine monophosphate (Ia) at its 5′‐methyl‐dihydrogen monophosphate group is a reactive gemcitabine phosphate carbodiimide ester intermediate (II) complex (Figure 1).90 Addition of the reactive gemcitabine phosphate carbodiimide ester intermediate to IgG formulated in imidazole buffer at pH 6.0 preferentially and specifically produces a transient Stage‐II amine‐reactive gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazolide (III) intermediate (Figure 1).90 The Stage‐II amine‐reactive gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazolide intermediate then was reacted in a highly preferential manner with the aliphatic ε‐monoamine of lysine residue side chains within the amino acid sequence of anti‐IGF‐1R monoclonal IgG resulting in the synthesis of the gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] (IV) end product (Figures 1 and 2).90 The relatively high molar ratio for gemcitabine monophosphate to 1‐ethyl‐3‐[3‐dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide (50:1) was utilized to both maximize production of the Phase I and Phase II intermediates and maximally deplete residual 1‐ethyl‐3‐[3‐dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide remaining within the reaction mixture. Preferential reaction with the ε‐monoamine of lysine amino acid residues is attributed to their significantly greater basicity compared to aromatic amines such as those found at the C4 position of gemcitabine due to the mesomeric effect conferred by aromatic ring structures. The covalent phosphoramide bond structure is highly stable at 4 °C or in whole plasma or tissue culture media like environments containing 5% plasma or 5% serum albumin90 in contrast to strictly aqueous buffer solutions devoid of biological proteins where at 37 °C, approximately a 12% total liberation rate occurs over a 100‐hour period.91 Compared to previous organic chemistry reaction regimens utilized to synthesize covalent immunochemotherapeutics,38, 64, 75, 76, 92 the Stage‐I/Stage‐II reaction for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] required a relatively short duration to minimize hydrolytic decomposition of the amine‐reactive phosphorylimidazolide intermediate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Organic chemistry reaction format of the multistage synthesis scheme for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R]. Stage‐I – Reaction Scheme (Plate Row #1): reaction of the gemcitabine‐5′ monophosphate group (Ia) with 1‐ethyl‐3‐[3‐dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide (Ib) to transiently form a reactive gemcitabine‐5′‐monophosphate carbodiimide ester intermediate complex (II); Stage‐II – Reaction Scheme (Plate Row #2): rapid and spontaneous conversion of the transient Phase I reactive intermediate (II) to the Stage‐II gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazolide amine‐reactive intermediate (III) in the presence of imidazole. Stage‐III – Reaction Scheme (Plate Row #3): reaction of the Stage‐II gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazolide amine‐reactive intermediate (III) with the ε‐monoamine of lysine residues within the amino acid sequence of anti‐IGF‐1R monoclonal IgG immunoglobulin resulting in the synthesis of a covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic (IV)

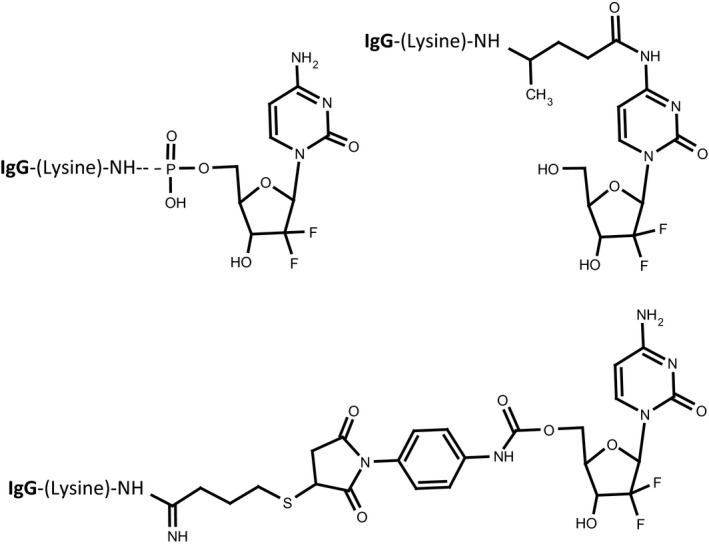

Figure 2.

Bond structures generated during organic chemistry reactions utilized to synthesize different covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics. Legends: (Plate‐1) gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[IgG] utilizing a heterobifunctional phosphate/amine carbodiimide analog in the presence of imidazole; (Plate‐2) gemcitabine‐(C4‐methylcarbamate)‐[IgG] synthesized utilizing a heterobifunctional isocyanate/maleimide covalent bond forming reagent following IgG immunoglobulin prethiolation;75 and (Plate‐3) gemcitabine‐(C2 ‐methylhydroxylamide)‐[IgG] synthesized utilizing a heterobifunctional amine‐selective/photoactivated non‐selective covalent bond forming reagent76

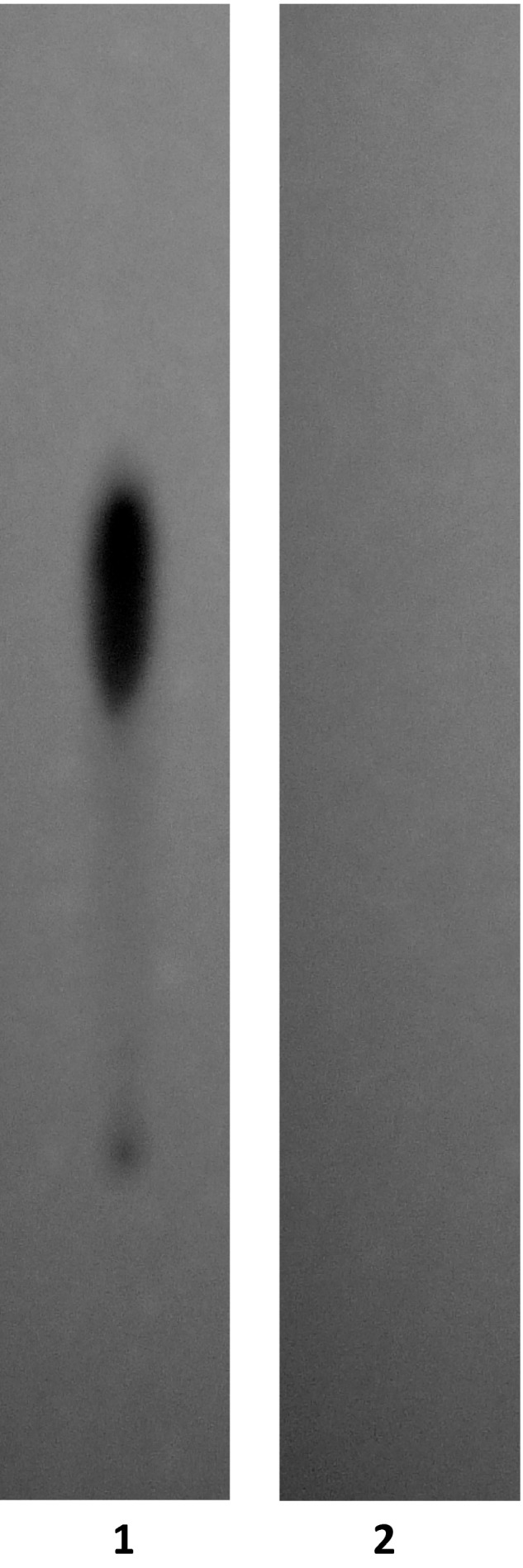

Serial microfiltrations (MWCO = 10‐kDa) of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] consistently yielded a Phase III covalent immunochemotherapeutic end product that was devoid of any residual ‘free’ non‐covalently bound gemcitabine detectable by standardized analytical HP‐TLC (UV 254 nm) analysis of highly concentrated formulations (Figure 3).38, 64, 75, 76, 92 High concentrations of monoclonal IgG as a molecular component of the covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic effectively quenched UV detection of any chemotherapeutic moiety at the application origin. Results from these analyses were highly analogous to findings attained in previous investigations for covalent epirubicin38, 64, 92 and gemcitabine75, 76 immunochemotherapeutics that contained only ≤3–4% of the total chemotherapeutic content as non‐covalently bound chemotherapeutic which cannot be removed by further serial applications of either microscale size exclusion column chromatography or microfiltration methodologies.93

Figure 3.

Evaluation of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] by analytical HP‐TLC for the detection of residual gemcitabine not covalently bound to anti‐IGF‐1R immunoglobulin. Legends: (Lane‐1) Stage‐II gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazolide amine‐reactive intermediate and (Lane‐2) Stage‐III covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic following serial microfiltration (MWCO = 10‐kDa). Standardized gemcitabine‐equivalent concentrations of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] and the gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazolide amine‐reactive intermediate were applied to HP‐TLC plates (silica gel, 250‐μm thickness, UV 254‐nm indicator) and developed utilizing a propanol/ethanol/H20 (17:5:5 v/v) mobile phase. Identification of any residual gemcitabine or unreacted gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazolide in the Stage‐III covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic was subsequently determined by direct UV illumination. High concentrations of monoclonal IgG as a molecular component of covalent of the gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic effectively quench UV detection of any chemotherapeutic moiety at the application origin

Covalent bonding of gemcitabine to immunoglobulin during the synthesis covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphor‐amidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was validated through the interpretations of HP‐TLC analyses and pulmonary adenocarcinoma ex vivo tissue culture‐based antineoplastic cytotoxicity. In the specialty of high‐pressure column chromatography and HP‐TLC analyses, mobile solvent phases are frequently used to separate small‐molecular‐weight pharmaceuticals from plasma proteins at extraction efficiencies that routinely approach 95% to 98% or higher.38, 64, 75, 76, 92 Analysis of covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] by HP‐TLC analysis performed with matched standardized reference controls did not detect the presence of any ‘free’ non‐IgG bound gemcitabine following exhaustive serial microfiltration.(Figure 3) Samples were measured spectrophotometrically at 235 nm, and total IgG concentrations were specifically measured using a chemical‐based assay. Based on the application of standardize reference control curves for both gemcitabine and IgG and the difference between the spectrophotometric absorbance at 235 nm and the chemical‐based assay for IgG, it was possible to determine the molar concentration of both gemcitabine and IgG contained in purified gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] preparations. The last phase of validation was based on the delineation of the antineoplastic cytotoxic potency of covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] against pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) cell populations. Mass spectrometry analysis (LC‐MS‐MS, MALDI TOF) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) could potentially have been performed in an attempt to detect covalent bonding of gemcitabine to anti‐IGF‐1R, but the detection of gemcitabine‐peptides is difficult to convincing authenticate. A serious limitation and a source of false assumption associated with the application of these forms of instrumentation is that they cannot simultaneously establish purity. Although it might be possible to detect whether there might be some gemcitabine covalently bound to IgG in a preparation, mass spectrometry is not capable of also determining what percent of the total amount of chemotherapeutic contained in a formulation is not in a ‘free’ non‐protein bound form. Conversely, HP‐TLC analysis can much more convincingly and efficiently be applied to simultaneously determine both purity and validating covalent bond formation between gemcitabine and IgG when applied in concert with appropriate standardized reference controls.

2.2. Molar incorporation index

The calculated gemcitabine molar incorporation index for covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was 2.67:1 utilizing the organic chemistry reaction scheme to form a covalent phosphoramide bond at the 5′‐methyl‐dihydrogen‐phosphate group of gemcitabine (Figure 1). Microfiltration (MWCO = 10‐kDa) provided substantially greater yield levels for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] than did the removal of residual gemcitabine and unreacted chemical reagents by microscale size exclusion column chromatography.

2.3. Mass‐separation analysis for detection of polymerization and fragmentation

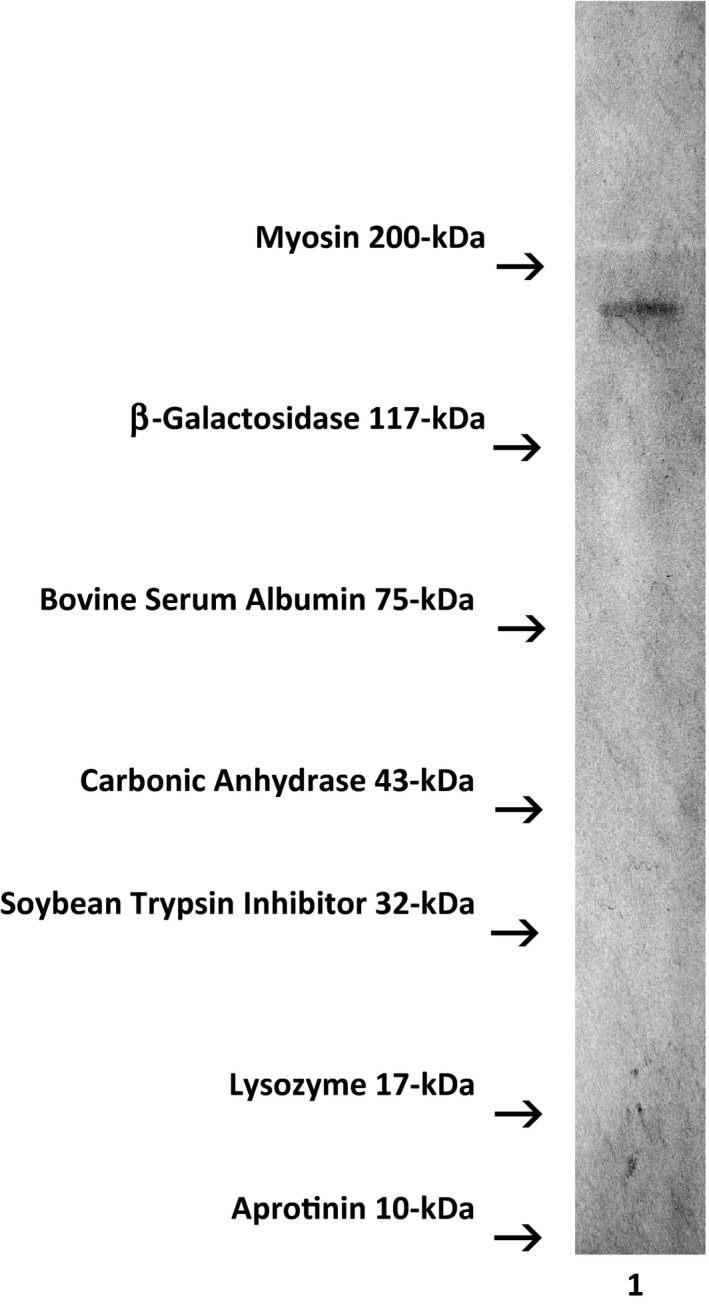

Molecular weight profile analysis of covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutics mass separated by SDS‐PAGE in combination with ligand‐blot detection analyses and chemiluminescent autoradiography recognized a single primary condensed band of 150 kDa between a molecular weight range of 5.0 kDa to 450 kDa (Figure 4) Profiles consistent with low molecular weight fragmentation (proteolytic/hydrolytic degradation) or large molecular weight IgG‐IgG polymerization were not detected (Figure 4). The observed molecular weight of 150 kDa for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] directly corresponds with the known molecular weight/mass of reference control anti‐IGF‐1R monoclonal immunoglobulin fractions (Figure 4). Analogous results have been reported for similar covalent immunochemotherapeutics.38, 41, 64, 75, 76, 92, 94 A set of rainbow color‐coded molecular weight markers were applied as standard reference controls that were developed by SDS‐PAGE and laterally transfer onto nitrocellulose membrane in concert with covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic. Rainbow color‐coded molecular weight markers are not detectable by chemiluminescent autoradiography but can be detected by direct visual observation.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the molecular weight profile for the covalent immunochemotherapeutic gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] relative to reference control anti‐IGF‐1R monoclonal immunoglobulin fractions and conventional molecular weight standards. Legends: (Lane‐1) gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R]. The covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutic and monoclonal immunoglobulin fractions were size‐separated by non‐reducing SDS‐PAGE followed by lateral transfer onto sheets of nitrocellulose membrane to facilitate detection with HRPO‐Protein G conjugate. Subsequent analysis entailed incubation of membranes with a HRPO chemiluminescent substrate and the acquisition of autoradiography images. The known molecular weight for IgG is 150 kDa

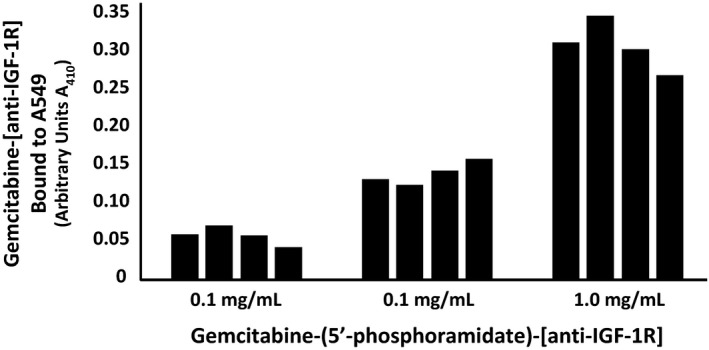

2.4. Cell‐ELISA total membrane IgG binding analysis

Total IgG in the form of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] bound on the external surface membrane of adherent pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) monolayer populations was detected and measured by cell‐ELISA (Figure 5). Increases in gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] formulated at the standardized immunoglobulin‐equivalent concentrations of 0.010, 0.10, and 1.00 μg/mL corresponded with progressive elevations in the total amount of membrane‐bound IgG (Figure 5). Collectively results from cell‐ELISA analyses validated the retained selective binding avidity of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] for external membrane IGF‐1R receptor sites highly overexpressed on the exterior surface membrane of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) monolayer populations (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Detection of total IgG immunoglobulin in the form of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] selectively bound to the exterior surface membrane of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic formulated at gradient IgG immunoglobulin‐equivalent concentrations was incubated in direct contact with triplicate monolayer populations of chemotherapeutic‐resistant human pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) over a 4‐hour time period. Total IgG immunoglobulin bound to the exterior surface membrane was then detected and measured by cell‐ELISA

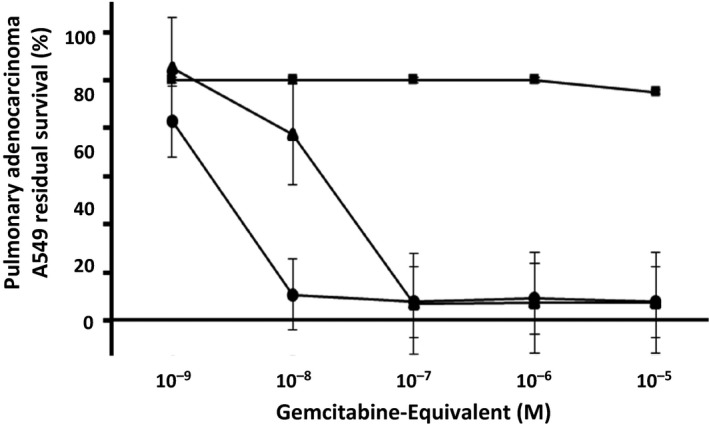

2.5. Antineoplastic cytotoxic potency

Nearly identical levels of antineoplastic cytotoxic potency were detected individually for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] and gemcitabine against pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) populations when challenged with gemcitabine‐equivalent concentrations at and between 10−9 m to 10−6 m over a 192‐hour incubation period (Figure 6). Antineoplastic cytotoxicity of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] increased rather dramatically at and between the standardized gemcitabine‐equivalent concentrations of 10−9 m, 10−8 m, and 10−7 m, which corresponded with lethal cancer cell death percentage values of 0.0%, 22.7%, and 93.1% (100%, 77.3%, and 6.9% residual survival), respectively (Figure 6). The antineoplastic cytotoxicity of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] against pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) was at or near maximum levels when formulated at and between the standardized gemcitabine‐equivalent concentrations of 10−7 m, 10−6 m, and 10−5 m, which correlated with non‐viable percentage values of 93.1%, 92.6%, and 92.5% (6.9%, 7.4%, and 7.5% residual survival), respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relative antineoplastic cytotoxic potency of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] against chemotherapeutic‐resistant pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Legends: (▲) gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R]; (●) gemcitabine chemotherapeutic; and (■) monoclonal anti‐IGF‐1R IgG immunoglobulin formatted at matched standardized concentrations. Analyses of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] and gemcitabine were performed in triplicate at gradient standardized (gemcitabine‐equivalent) concentrations. Gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] and gemcitabine were bother separately incubated in direct contact with monolayer populations of chemotherapeutic‐resistant pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) for a period of 192 h. Antineoplastic cytotoxic potency was measured using a MTT cell vitality assay relative to matched negative reference controls

Gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] produced greater antineoplastic cytotoxicity against populations of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) than did either gemcitabine‐(C5‐ ‐methylcarbamate)‐[anti‐HER2/neu]75 or gemcitabine‐(C4‐amide)‐[anti‐HER2/neu] against chemotherapeutic‐resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr‐3) applying comparable incubation periods (Figure 6).76

3. Discussion

Several new classes of chemotherapeutic agents have been developed that have a high degree of potency, but their prominent physiological toxicity prevents or limits there systemic administration unless they are covalently bound to carrier molecules of a relatively large size and weight. Such requirements have motivated the development of several covalent immunochemotherapeutics possessing moieties that include (i) colicheamicins that promote DNA strand cleavage for CD22(+) lymphoma (ozogamicin‐inotuzumab) and CD33(+) leukemia (ozogamicin‐gemtuzumab, 2010 withdrawn); (ii) monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) tubulin inhibitor for GP‐NMP(+) melanoma, glioma, and breast cancer (MMAE‐glembatumumab); or CD30(+) Hodgkin's lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (MMAE‐brentuximab); and (iv) maytansines/maytansinoids tubulin inhibitors for HER1/neu(+) adenocarcinomas/carcinomas (emtansine‐trastuzumab); CD44v6(+) metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (mertansine‐bivatuzumab); CD56(+) ovarian carcinoma, small cell lung cancer, and multiple myeloma (mertansine‐lorvotuzumab); and CanAg(+) colorectal cancer (mertansine‐cantuzumab or ravtansine‐cantuzumab).

In contrast to the anthracycline class of chemotherapeutics,38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 a comparatively limited body of investigation has been devoted to the molecular design and optimization of organic chemistry reactions that can be utilized in synthesis regimens for covalently bonding non‐anthracycline small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutics to biologically relevant molecular platforms. Classical small molecular weight chemotherapeutics that have been synthesized and become available commercially as covalent immunochemotherapeutics include (i) irinotecan metabolite SN38 that inhibits topoisomerase‐I for CD74(+) multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/CLL (SN38‐milatuzumab); or CEA(+) lung, breast, and colorectal adenocarcinomas/carcinomas (SN38‐labetuzumab); or EPG‐1(+) or TROP‐2(+) adenocarcinoma and carcinoma classified as triple‐negative breast cancer, small‐cell lung cancer, and colorectal cancer (SN38‐hRS7 or IMMU132); and (ii) anthracyclines that inhibit topoisomerase‐II and nucleotide strand formation while promoting ‘free’ oxygen radical formation and chromatin histone eviction with efficacy against CD74(+) chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma (doxorubicin‐milatuzumab).

Gemcitabine has been covalently bound to a relatively small array of biologically relevant molecular platforms such as peptide sequences and large molecular weight proteins, in addition to the pharmaceuticals, benzodiazepine,95 and coumarin.96 More frequently, gemcitabine has been covalently bound to relatively low molecular weight platforms such as linoleic acid,97 poly(lactic‐co‐glycolic) acid,98 poly‐l‐glutamic acid (PGNa),99 and polyethylene glycol100 phospholipids (e.g., cardiolipin,101 1‐dodecylthio‐2‐decyloxypropyl‐3‐phosphatidic acid,102 and CO‐1014). A very limited number of investigations had previously described organic chemistry reaction regimens for covalently bonding gemcitabine to IgG,75, 76 or fragments of IgG (e.g., F(ab’)2 and Fab’) or trophic receptor ligands (e.g., EGF EGFR) capable of functioning as large molecular weight platforms that afford properties of selective ‘targeted’ chemotherapeutic moiety delivery. Some covalent gemcitabine biopharmaceuticals have demonstrated significant antineoplastic potency against breast cancer in both ex vivo (MCF‐7 cell line) and in vivo (MCF‐7 xenographs) neoplastic disease models.97 Gemcitabine can be covalently bound at its cytosine C2‐NH2 monoamine59, 95, 103, 104, 105 to either a biologically relevant molecules or reagents in a manner that transiently creates a chemically reactive gemcitabine intermediate utilizing organic chemistry reactions that are similar to those employed in molecular strategies for synthesizing covalent anthracycline immunochemotherapeutics (Figures 1 and 2).38, 44, 46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 61 Gemcitabine has also been covalently bound at its C2‐NH2 monoamine group to the carboxyl group of a second biologically relevant molecular platform using a carbodiimide98, 100 or a combination of ethylchlorocarbonate and triethylamine formulated in an anhydrous solvent system (tetrahydrofuran/THF or dimethylformamide/DMF)106 resulting in formation of an amide bond structure.98, 100 A somewhat unique synthesis method entails covalent bonding the C2‐NH2 monoamine of gemcitabine to amine‐reactive N‐hydroxysuccinimide esters where UV‐reactive analogs like succinimidyl 4,4‐azipentanoate are then covalently bonded to a biologically relevant large molecular weight platform by exposure to UV light (354 nm: range 320–370 nm) (Figures 1 and 2).76 Alternatively, gemcitabine at the C5‐OH hydroxyl position can be covalently bound to phosphate groups utilizing benzoic anhydride formulated in ethanol.102 In this synthesis method, the C5‐OH is initially protected with tert‐butyldimethylsilyl chloride, which is then removed using tetrabutylammonium fluoride,102 while the C3‐OH is protected with acetic anhydride in pyridine.102 Gemcitabine at the C5‐OH methylhydroxy position can also be covalently bound to isocyanate analog similar to N‐[p‐maleimidophenyl]isocyanate resulting in the formation of a carbamate group where the maleimide moiety subsequently forms a covalently bond at reduced cysteine sulphydryls or thiolated lysine amino acid residues found within biologically relevant peptide sequences or large molecular weight proteins (Figures 1 and 2).75 Similarly, the central CH2‐OH hydroxyl group between two phosphate groups can be reacted with a succinic anhydride in combination with 4‐dimethylamino‐pyridine formulated in 1,2‐dichloroethane to yield a succinyl‐glycerol dimethyl ether.101 In the presence of a carbodiimide, the succinyl‐glycerol dimethyl ether analog reacts with protected gemcitabine [4‐N‐3O‐bis(tert‐butoxycarbonyl)‐gemcitabine] where the shielding group is subsequently removed with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in dichloromethane.101 Gemcitabine at the C5 CH2‐OH methylhydroxyl can be covalently reacted with a carboxyl group utilizing a carbodiimide in combination with dimethylaminopyridine formulated in N,N‐dimethylformamide.99

The multistage organic chemistry reaction scheme implemented to synthesize gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] represents a notable departure from those previously described for preparation of covalent gemcitabine‐ligand preparations.39, 95, 99, 102, 105, 107, 108 Organic chemistry reaction regimens utilizing EDC for covalently bonding gemcitabine monophosphate to immunoglobulin or other biologically relevant protein have to date not been previously described. Initially, the multistage organic chemistry reaction scheme results in the generation of a transient Stage‐I gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoryl) carbodiimide ester‐reactive intermediate that in the presence of imidazole is rapidly transformed into a more stable Stage‐II gemcitabine‐5′‐phophorylimidazole amine‐reactive intermediate (Figure 1). Formulation of gemcitabine‐5′‐methyl‐dihydrogen‐phosphate at a relatively large molar excess to the carbodiimide serves to promote (i) maximal yield of the Stage‐II amine‐reactive gemcitabine intermediate, (ii) maximal and rapid carbodiimide reagent depletion within an aqueous‐based buffer system, and (iii) substantially lower ultimate risk of IgG‐IgG polymerization. In Stage‐III of the multistage organic chemistry reaction scheme implemented, the Stage‐II gemcitabine‐5′‐phophorylimidazole amine‐reactive intermediate forms a covalent phosphoramide bond at the 5′‐methyl‐dihydrogen‐phosphate group of gemcitabine. In the presence of anti‐IGF‐1R, the covalent bond with the ε‐monoamine group of lysine residues within the amino acid sequence results in the formation of a 5′‐phosphoramidate bond structure and production of a covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic end product (Figure 1).109, 110 Optimum results are attained when amine (R‐CH2‐NH2 + of lysine), and less frequently carboxyl (R‐CH2‐CO2 − of glutamate), hydroxyl (R‐CH2‐OH of serine), or sulphydryl (R‐CH2‐SH of cystine) chemical groups associated with amino acid residues within the sequence of IgG or trophic ligands are (i) relatively abundant (e.g., protein sulphydryl R‐SH groups are frequently not abundant) and (ii) physically available (subject to minimal steric hindrance phenomenon).

Relative effectiveness of the multistage organic chemistry reaction scheme implemented for the synthesis of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] is in part demonstrated by attainment of a 2.67:1 gemcitabine:IgG molar incorporation index. Such qualities are further substantiated by comparative experimental results from analogous synthesis methods in related investigations where 1‐ethyl‐3‐[3‐dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide in combination with imidazole has been used to covalently bond fludarabine,79 dexamethasone‐C21‐phosphate, and other phosphorylated pharmaceutical analogs to monoclonal IgG fractions. The gemcitabine:IgG molar incorporation index of 2.67:1 for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was comparatively greater or equivalent to values obtained in previous investigations utilizing other covalent bond forming agents for the synthesis of covalent immunochemotherapeutics such as (i) gemcitabine‐(C5‐methylcarbamate)‐[anti‐HER2/neu] (Gem:IgG = 1.1‐to1);75 (ii) gemcitabine‐(C4‐amide)‐[anti‐HER2/neu] (Gem:IgG = 2.78–1);76 (iii) epirubicin‐(C3‐amide)‐[anti‐HER2/neu] (Epi:IgG = 0.275–1);38 (iv) epirubicin‐(C3‐amide)‐[anti‐EGFR] (Epi:IgG = 0.407–1);38 and (vi) epirubicin‐(C13‐imino)‐[anti‐HER2/neu] (Epi:IgG = 0.400–1).64

In addition to the option of modifying the classical variables of temperature and concentration (molar excess) and extending the reaction time duration to enhance efficiency of chemical reactions, there are several other parameters that likely contributed to the gemcitabine:IgG molar incorporation index for gemcitabine‐(5′‐methyldihydrogen‐phosphoramide)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] such as the (i) lack of a requirement for prethiolation of peptide sequences or large molecular weight proteins; (ii) potentially greater chemical reactivity of carbodiimide analogs compared to other previously applied covalent bond forming reagents; (iii) imidazole‐selective enhancement of carbodiimide reagent phosphate reactivity; and (iv) formation of a covalent bond with an available phosphate at the 5′‐methyl‐dihydrogen‐phosphate position in contrast to a phosphate (Ar‐PO4 −), carboxyl (Ar‐CO2 −), amine (ArNH2 +), or sulphydryl (Ar‐SH) chemical group located directly on an aromatic ring structure (Figures 1 and 2). The latter quality reduces both the degree of steric hindrance phenomenon at the C2 monophosphate group of gemcitabine and reduces the influence of the five or six electron orbital clouds above the plane of aromatic ring structures that often modify the chemical properties of phosphate and other functional groups. Complementing the effectiveness of the organic chemistry reactions, the final yield of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF1R] was substantially improved by implementing both a multistage organic chemistry reaction scheme (in preference to a single‐phase ‘mixed’ regimen) in concert with serial microfiltrations (MWCO 10‐kDa) instead of microscale column chromatography for separation and purification of the Stage‐III covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutic end product.

The organic chemistry reactions utilized in the multistage synthesis regimen for gemcitabine‐(5′‐methyldihydrogen‐phosphoramide)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] have several distinct advantages and attributes. Most notable in this regard is the (i) comparatively rapid individual and collective duration for Stage‐I, Stage‐II, and Stage‐III reactions; (ii) relatively reaction efficiency; (iii) high yield of covalent gemcitabine immunotherapeutic end product (IgG‐based determination); (iv) option of producing a stable Stage‐II gemcitabine‐5′‐phosphorylimidazole amine‐reactive intermediate that can withstand short‐to‐long‐term preservation for future utilization; (v) flexibility of allowing substitution of other biologically relevant molecular platforms in place of anti‐IGF‐1R; (vi) flexibility of non‐dedicated organic chemistry reactions that allow substituting other chemotherapeutic agents or pharmaceuticals in place of gemcitabine; (vii) low to moderately low level of technical difficulty; and (viii) the requirement of marginal dependence on access to advanced forms of laboratory instrumentation. Biologically relevant molecular platforms utilized for the purpose of selectively ‘targeting’ the delivery of chemotherapeutic moieties should ideally possess one or more characteristics that facilitate and promote; (i) binding avidity that is restricted to unique or highly overexpressed ‘sites’ on the exterior surface membrane of a given cell type; (ii) binding avidity that blocks or mimics physical interactions of endogenous trophic ligands with their corresponding membrane receptors (e.g., suppresses trophic ligand binding at cell membrane receptor sites); (iii) binding avidity that inhibits or enhances the biological function of a cell membrane‐associated receptor sites or biochemically active enzyme (e.g., suppresses membrane trophic receptor activity or function); and/or (iv) transiently or permanently reduces expression density of membrane trophic receptors (e.g., induced declines in surface membrane expression through mechanisms of IgG‐induced receptor‐mediated endocytosis, thereby promoting internalization into the cytosol environment). Other highly desirable attributes of molecular platforms applied to facilitate properties of selective ‘targeted’ delivery are (vi) innately large molecular weight/size sufficient enough (e.g. >60‐kDa) to prolong plasma pharmacokinetic profiles of chemotherapeutic moieties due to delayed or prevention of excretion by glomerular filtration (renal plasma clearance); and (vii) ability in vivo to stimulate complementary endogenous host immune responses such as antibody‐dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement‐mediated cytolysis (CMC), and opsonization/phagocytosis.

The endogenous trophic membrane receptors, EGFR (anti‐EGFR), HER2/neu (anti‐HER2/neu), IGF‐1R (anti‐IGF1R), and VEGFR (anti‐VEGFR), are uniquely or highly overexpressed by an array of neoplastic adenocarcinoma and carcinoma cell types and can be induced to internalize by mechanisms of receptor‐mediated endocytosis in response to binding of receptor ligands or IgG. Interestingly, some haematopoietic neoplasias like chronic lymphocytic leukemia also express IGF‐1R,28 and this receptor represents a site of interest on the external surface membrane for the purpose of facilitating selective ‘targeted’ delivery of chemotherapeutics or other pharmaceutical agents. Similar to monoclonal anti‐HER2/neu (Herceptin) and anti‐EGFR (cetuximab) immunoglobulin fractions on neoplastic adenocarcinoma and carcinoma cell types, both anti‐CD20 (rituximab, ofatumumab) and anti‐CD52 (alemtuzumab) disrupt growth and vitality of leukemia and lymphoma cell types. Both anti‐CD20 (rituximab, ofatumumab)24, 30 and anti‐CD52 (alemtuzumab)25 are effective against B‐cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B‐CLL) cell populations. Simultaneous anti‐CD20 (rituximab) in combination with cyclophosphamide–doxorubicin–vincristine–prednisone (CHOP) increases survival over CHOP alone in conditions of high‐grade lymphomas.111 Unconventional chemotherapeutic agents that have been incorporated as pharmaceutical moieties within covalent immunochemotherapeutics with efficacy against hemopoietic cancer cell types include mertansine (maytansinoid analog) in the form of lorvotuzumab‐mertansine (anti‐CD56 for multiple myeloma). Alternatively, bivatuzumab‐mertansine, cantuzumab‐mertansine, and trastuzumab‐emtansine (T‐DM1) are effective against metastatic head and neck cancer (anti‐CD44), colorectal cancer (anti‐CanAg), and HER2/neu‐positive adenocarcinomas/carcinomas (anti‐HER2/neu), respectively.

The covalent immunochemotherapeutic gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] possesses several distinct attributes with regard to chemical composition and molecular structure. Most prominent in this regard are the following characteristics: (i) specific activity greater than 1:1 based on a calculated gemcitabine:IgG molar incorporation index of 2.67:1; (ii) covalent bonding of gemcitabine to anti‐IGF‐1R through the generation of a 5′‐phosphoramidate bond structure that at least theoretically provides a relatively high level of bioavailability for the gemcitabine moiety within the acidic microenvironment of the phagolysosome following internalization by mechanisms of selective ‘targeted’ IgG‐induced receptor‐mediated endocytosis; (iii) retained biological activity as a function of detectable gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] binding avidity for IGF‐1R complexes that are overexpressed on the external surface membrane of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) that in turn facilitates selective ‘targeted’ gemcitabine delivery; and (iv) the absence of any ‘foreign’ chemical group being introduced or added into the molecular structure and chemical composition of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] during the course of implementing organic chemistry reaction regimens for the synthesis of a 5′‐phosphoramidate bond structure in a manner that substantially decreases the probability of inducing a humoral immune response or type I immune hypersensitivity reactions.

Neoplastic cell types known to be relatively sensitive to the biological activity of gemcitabine include pancreatic carcinoma,4, 112 ovarian carcinoma,14, 15 small‐cell lung carcinoma,113 non‐small cell lung carcinoma,2 neuroblastoma,114 and leukemia/lymphoid102, 115 populations. Similarly, human promyelocytic leukemia,18, 39, 102 T‐4 lymphoblastoid clones,102 glioblastoma,39, 102 cervical epithelioid carcinoma,102 colon adenocarcinoma,102 pancreatic adenocarcinoma,4, 5, 100, 102 pulmonary adenocarcinoma,102 oral squamous cell carcinoma,102 and prostatic carcinoma59 have been found to be sensitive to gemcitabine and covalent gemcitabine‐(oxyether phopholipid) preparations. Gemcitabine has also been administered in combination with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and cisplatin following anthracycline failure in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.11 Within the various cell types of breast cancer, mammary carcinoma (MCF‐7/WT‐2′)102 and mammary adenocarcinoma (BG‐1)102 are known to be relatively resistant to the anthracyclines,11 gemcitabine, and gemcitabine‐(oxyether phopholipid) chemotherapeutic preparations.

Several variables associated with cancer cell biology directly influence the degree of selective ‘targeted’ delivery and antineoplastic cytotoxic potency evoked by chemotherapeutic moieties in gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] and other analogous covalent immunochemotherapeutics.38, 64, 75, 76, 92 Covalent bonding gemcitabine to a biologically relevant large molecular weight platform possessing binding avidity for a membrane‐associated site uniquely or highly overexpressed by a neoplastic cell type provides an opportunity for simultaneously achieving selective ‘targeted’ chemotherapeutic moiety delivery in addition to establishing a molecular mechanism for maximizing therapeutic efficacy and potency. Absolute uniqueness of membrane expression determines how selectively ‘targeted’ a chemotherapeutic moiety is delivered. In addition, density of membrane expression and the rate at which such sites are replenished following internalization by mechanisms of receptor‐mediated endocytosis ultimately determines the fraction of total chemotherapeutic (dose) that becomes (i) selectively deposited on the exterior surface membrane and (ii) concentrated by accumulation within the cytosol of ‘targeted’ neoplastic cell populations. Such variable therefore ultimately influences the extent of antineoplastic cytotoxic potency attained. Trophic membrane receptors like EGFR, HER2/neu, IGF‐1R, and VEGFR represent one class of ‘targets’ that can facilitate selective chemotherapeutic delivery because frequently they are uniquely overexpressed by many neoplastic cell types. Overexpressed membrane antigens relevant to treatment of leukemia and lymphoma include the cell‐differentiating proteins CD19 and CD20 are similar examples that are not known to possess binding avidity for any known endogenous tropic ligand, despite CD20 being known to also undergo internalization by mechanisms of receptor‐mediated endocytosis.

In instances when monoclonal IgG, IgG fragments (Fab’, F(ab’)2) or receptor ligands (e.g., EGF) are utilized to produce a covalent immunochemotherapeutic like gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] that has selective binding avidity for an endogenous membrane trophic receptor known to be internalized by mechanisms of receptor‐mediated endocytosis,116, 117, 118, 119 such molecular delivery platforms substantially increase transmembrane active transport of chemotherapeutic moieties. A beneficial consequence of this biological phenomenon is the capacity to increase intracellular chemotherapeutic concentrations to levels 8.5×118 to >100×117, 119 higher than those attainable by simple passive diffusion of conventional small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutics from the extracellular fluid compartment across intact cell membranes following intravenous injection at clinically relevant dosages. Although specific data for IGF‐1R receptor‐mediated endocytosis are somewhat limited for pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549), other neoplastic cell types like Lewis lung carcinoma (H‐59: highly metastatic subcell linage with a hepatic propensity) and mammary adenocarcinoma (MCF‐7) are known to internalize membrane IGF‐1R receptors by mechanisms of receptor‐mediated endocytosis at a rate of ≅2.1 × 104/cell (54%) and ≅4.5 × 104/cell (45%) within a 1‐hour IGF incubation period.120 Related investigations have demonstrated that metastatic multiple myeloma is capable of internalizing approximately 8 × 106 molecules of anti‐CD74 monoclonal antibody per day.121 Given this perspective, three of the most critically important numerical variables related to cancer cell biology that determines the antineoplastic cytotoxic potency of covalent immunochemotherapeutics like gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R], gemcitabine‐(C5‐methylcarbamate)‐[anti‐HER2/neu],75 gemcitabine‐(C4‐amide)‐[anti‐HER2/neu],76 epirubicin‐(C3‐amide)‐[anti‐HER2/neu],38 epirubicin‐(C3‐amide)[anti‐EGFR],38 and epirubicin‐(C13‐imino)‐[anti‐HER2/neu]64 are the (i) expression density of the external membrane‐associated endogenous trophic receptor ‘targets’ relative to normal healthy tissues and organ systems; (ii) rate of internalization by mechanisms of receptor‐mediated endocytosis; and (iii) rate that receptors on the external surface membrane are replenished following internalization by receptor‐mediated endocytosis. Furthermore, it is vitally important that the external membrane‐associated sites chosen to facilitate selective ‘targeted’ chemotherapeutic delivery be able to functionally undergo phenomenon identical or analogous to receptor‐mediated endocytosis to avoid simple ‘coating’ of the external surface of cancer cell membranes. Such a prerequisite is relevant when the chemotherapeutic moiety exerts a mechanism of action that is entirely dependent upon their ability to modify biological functions of molecular entities residing within the cytosol or nucleus to exert a cytotoxic effect. Such a prerequisite would not be a requirement for anticancer agents that instead alter or disrupt the physical integrity of cancer cell membranes or the function of complexes that are an integral component of membrane structures.

Despite the inhibitory characteristics of anti‐HER2/neu, anti‐EGFR, anti‐IGF‐1R, and similar monoclonal immunoglobulin‐based modalities on the function of membrane trophic receptors, they primarily in vivo suppress only proliferative growth and vitality of cancer cells while being almost invariably incapable of evoking cytotoxic activity sufficient to independently resolve successfully most aggressive or advanced forms of neoplastic disease.122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138 Inability of most immunoglobulins that have binding avidity for trophic membrane receptors to exert significant cytotoxic efficacy in vivo coincides with detection of increases in cell‐cycle G1‐arrest, cancer cell transformation into states of apoptosis resistance,123 and preferential selection for resistant subpopulations.124, 128 In addition, this scenario can be further complicated by frequent reversal of tumor growth inhibition124 and relapse trophic receptor overexpression122 upon cessation and withdrawal. Greater levels of antineoplastic cytotoxicity are attainable when antitrophic receptor IgG is utilized in dual combination with conventional chemotherapeutics or other cancer treatment modalities.139, 140, 141 Development of resistance has also been detected for monoclonal IgG with binding avidity for cell differentiation proteins such as anti‐CD20 (veltuzumab, ofatumumab) and anti‐CD52 (alemtuzumab). Mechanisms of resistance associated with monoclonal IgG fractions with binding avidity for these and other membrane‐associated cell differentiation antigens are attributed to (i) accelerated rates of receptor‐mediated endocytosis prior to ADCC/CMC/opsonization,142, 143 (ii) monocyte/macrophage CD20/CD52 ‘shaving’ or trogocytosis,144 and (iii) immune evasion as a consequence of immunosuppressive mediators liberated from cancer cell populations.145, 146 Interestingly, ofatumumab has been approved for B‐CLL resistant to alemtuzumab and fludarabine.

In an ex vivo tissue culture environment, most types of therapeutic monoclonal IgG with binding avidity for overexpressed trophic membrane receptors evoke very limited or a total lack of selective antineoplastic cytotoxicity or even a detectable degree of induced inhibition of vitality or viability.38, 67, 68, 71, 78, 94 Multiple reasons contribute to this observation, but some of the most prevalent in this regard include the (i) relatively low concentration of endogenous trophic ligands present in conventional tissue culture media (e.g., 5% to 10% bovine serum); (ii) relatively brief incubation periods employed to access efficacy and potency (e.g., 3 to 8 days); and (iii) the absence of any influence from activation of directed host immune responses. In an in vivo environment, monoclonal IgG fractions including anti‐HER2/neu, anti‐EGFR, and anti‐IGF‐1R with binding avidity for trophic membrane receptors produce detectable declines in neoplastic cell proliferation and vitality. However, monoclonal IgG bound to antigenic sites on the external surface membrane of neoplastic cells can also selectively induce activation of ‘targeted’ host immune responses that can produce a significant cytotoxic effect. Most notable in this regard is antibody‐dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement‐mediated cytolysis (CMC), and opsonization/phagocytosis which serve as the primary mechanism by which anti‐CD20 and anti‐CD52 attain efficacy against leukemia neoplastic disease states.

The covalent bonding of gemcitabine or other small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutics to biologically relevant molecular platforms that have a relatively large size (e.g., IgG MW = 150‐kDa, EGF MW = 6.05‐kDa) imparts several distinct characteristics that serve as beneficial attributes that often are not recognized or appreciated. Besides serving as a means for facilitating selective ‘targeted’ delivery of chemotherapeutic moieties, the immunoglobulin component (IgG MW 150‐kDa) of covalent immunochemotherapeutics has a total combined molecular weight that is substantially larger than most conventional small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutics (gemcitabine MW 263.198‐Da; fludarabine MW 365.212‐Da; dexamethasone MW 392.461‐Da). Due to this physical property, covalently bound moieties in biopharmaceuticals like the immunochemotherapeutics, gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R], fludarabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R], or dexamethasone‐(C21 ‐phosphoramide)‐[anti‐EGFR] ultimately do not selectively bind to, nor do covalent immunopharmaceuticals (MW 150,000‐Da) extensively diffuse passively across intact external surface membrane structures of normal healthy cell populations residing within tissues and organ systems. The asset of selective ‘targeted’ delivery associated with covalent immunochemotherapeutics is therefore attributed to, and heavily dependent upon both the selective binding avidity and relatively large molecular weight (size) of the IgG component.

A beneficial attribute determined by the relatively large size of IgG molecule or other relatively large molecular platform is a presumed degree of steric hindrance phenomenon that reduces accessibility of covalently bound chemotherapeutic or other pharmaceutical moieties to P‐glycoprotein52, 147, 148, 149 while functioning as a non‐selective transmembrane efflux ‘pump’ (MDR‐1: multidrug resistance protein).39 As P‐glycoprotein is commonly responsible for mediating chemotherapeutic resistance among many different neoplastic cell types,147, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154 selective ‘targeted’ delivery of chemotherapeutic moieties represents a molecular‐based strategy for increasing potency and efficacy. Similar in concept, the relatively large molecular weight of IgG is of sufficient physical size to effectively delay or prevent renal excretion of a chemotherapeutic or other pharmaceutical moieties by glomerular filtration (MWCO 60‐kDa). Delaying or preventing renal excretion of a chemotherapeutic/pharmaceutical moiety in effect prolongs its plasma pharmacokinetic profiles (e.g., IgG = 150‐kDa), increases plasma concentrations, and reduces acute burdens on biochemical metabolizing pathways and excretory processes.

The covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic was only slightly less potent than gemcitabine at the chemotherapeutic‐equivalent concentration of 10−9 m, and much less potent at 10−8 m while both produced maximal antineoplastic cytotoxicity that was essentially equivalent to approximately 0% residual survival (100% antineoplastic cytotoxicity) of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) at and between the concentrations of 10−7 m, 10−6 m, and 10−5 m (Figure 6). Although gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] was more potent against pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549) than either gemcitabine‐(C2‐methylcarbamate)‐[anti‐HER2/neu],155 or gemcitabine‐(C2 ‐methylhydroxylamide)‐[anti‐EGFR]76 against mammary adenocarcinoma, each of these three covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics at the lower range of chemotherapeutic‐equivalent concentrations exerted lower levels of ex vivo potency than did gemcitabine when evaluated utilizing a tissue culture‐based neoplastic disease model over a relatively brief incubation period. Given these observations, it is critically important to acknowledge that the major research objectives were to (i) develop a covalent immunochemotherapeutic that can serve as a molecular strategy for the selective ‘targeted’ delivery of gemcitabine and (ii) validate the applicability of the multistage organic chemistry reaction scheme for the synthesis of covalent immunochemotherapeutics or other covalent biopharmaceutical agents. Achieving a higher margin of safety through a combination of selective ‘targeted’ delivery and inhibition of the passive diffusion of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] across the intact external membranes of normal healthy cells in turn allows increasing clinical gemcitabine‐equivalent dosages to levels that are above those recommended for gemcitabine. Comparatively higher levels of antineoplastic potency for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] likely could have been attained if an alternative human cancer cell type or a relatively chemotherapeutic‐resistant cancer cell line had been selected as an ex vivo cancer model. The evaluation of the ex vivo efficacy of the vast majority of covalent immunochemotherapeutics reported to date have utilized non‐chemotherapeutic‐resistant populations of neoplastic cell types both to validate proof of concept and determine antineoplastic cytotoxic potency. Exceptions are chemotherapeutic‐resistant metastatic melanoma M21 (covalent daunorubicin immunochemotherapeutics synthesized using antichondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 9.2.27 surface marker)68, 71, 156; chemotherapeutic‐resistant mammary carcinoma MCF‐7AdrR (covalent anthracycline‐ligand chemotherapeutics utilizing epidermal growth factor (EGF) or an EDF fragment)157; and chemotherapeutic‐resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr‐3) populations (epirubicin‐anti‐HER2/neu and epirubicin‐anti‐EGFR, gemcitabine‐anti‐HER2/neu),38, 64, 75, 76, 92 and chemotherapeutic‐resistant pulmonary adenocarcinoma A549 (fludarabine‐(C2 ‐methylhydroxyphosphoramide)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R]).79

A high degree of probability exists that in vivo, gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF1R], gemcitabine‐(C2‐methylcarbamate)‐[anti‐HER2/neu],155 and gemcitabine‐(C2 ‐methylhydroxylamide)‐[anti‐EGFR]76 would provide planes of antineoplastic cytotoxic potency that would be at least equivalent to, if not surpass that of gemcitabine chemotherapeutic due to several contributing parameters. More specifically, under in vivo conditions, it is anticipated that the antineoplastic cytotoxicity of gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] would be further complemented by the attributes and advantages of (i) enhanced pharmacokinetic profiles; (ii) greater cytosol concentrations within ‘targeted’ cancer cell populations over time, all in collective concert with; and (iii) stimulation of the endogenous host immune responses of antibody‐dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement‐mediated cytolysis (CMC), and opsonization/phagocytosis subsequent to formation of membrane IgG–antigen complexes. Given this perspective, the covalent immunochemotherapeutic, gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] represents a potential molecular strategy for enhancing potency and effectiveness of the gemcitabine chemotherapeutic moiety relevant to the naturally low response rates and chemotherapeutic resistance detected in many neoplastic cell types that highly overexpress membrane trophic receptors and P‐glycoprotein, while at the same time simultaneously providing a greater margin of safety.

In addition to the potential for gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] to function as an effective anticancer agent, its chemical composition and molecular configuration in concert with the organic chemistry reactions implemented in the development of a multistage synthesis regimen can all collectively serve as a prototype reference template that can guide future development of other covalent immunochemotherapeutics or analogous biopharmaceutical agents. Relevant examples in this regard include synthesis regimens for decitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐CD19], clofarabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐CD20], and cytarabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐CD52], cladribine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐CD19], or 5‐azacitidine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐CD20] which each have a phosphorylated chemotherapeutic moieties. Covalent immunochemotherapeutics of this type would possess properties of selective ‘targeted’ delivery and be capable of exerting efficacy against various adenocarcinomas, carcino mas, or certain forms of leukemia and lymphoma.158, 159, 160 Importantly, it should be noted that in clinical oncology, the basic principles of pharmacology imply that the property of selective ‘targeted’ chemotherapeutic delivery is in general a more valuable quality than potency when the margin of safety is high because of the option for modifying therapeutic dosage.

4. Conclusion

The molecular strategy of selectively ‘targeting’ the delivery of pharmaceutical agents including conventional small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutics has the potential of affording increases in potency while simultaneously minimizing exposure of normal tissues and healthy organ systems. Molecular design and the corresponding organic chemistry reactions that can be employed to covalently bond gemcitabine to a monoclonal IgG or other biologically relevant peptide sequence or large molecular weight protein molecule have not previously been described in published reports. Attributes of the organic chemistry reactions scheme for the synthesis of the Stage‐III gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] end product include (i) a relatively brief reaction time for synthesizing the Stage‐III end product from the Stage‐II amine‐reactive intermediate; (ii) option of generating a stable Stage‐II gemcitabine amine‐reactive intermediate if an anhydrous Phase I and II solvent system is applied (e.g., DMSO, DMF); (iii) flexibility of utilizing other phosphate pharmaceutical analogs; (iv) ability to substitute other biologically relevant protein fractions in place of anti‐IGF1R; and (v) comparatively low level of dependency on advanced forms of instrumentation. Physical and functional attributes of the final Stage‐III gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] end product are (i) gemcitabine chemotherapeutic molar incorporation index of 2.67:1; (ii) lack of any ‘foreign’ or artificial chemical groups introduced into the final Stage‐III end product; (iii) retained IGF‐1R binding avidity; (iv) the absence of any detectable IgG–IgG polymerization or low molecular weight fragmentation. The lack of any 5‐carbon or 6‐carbon ring structures inserted into gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] end product during the course of implementing the organic chemistry reactions in the multistage synthesis regimen reduces the probability of inducing subsequent host humoral immune responses.

Covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics potentially can provide a spectrum of desirable attributes that are not possible with conventional small‐molecular‐weight chemotherapeutic agents. Most important in this regard is their ability to promote or facilitate (i) selective and continual pharmaceutical deposition on the exterior surface membrane of neoplastic cells; (ii) progressive pharmaceutical accumulation within the cytosol/intracellular compartment of neoplastic or immune cell populations to concentrations that are 8.5× to 100× greater than can be attained by simple passive diffusion; (iii) reducing the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic resistance mechanisms (e.g., P‐glycoprotein); (iv) potential opportunity to attain synergistic or additive antineoplastic cytotoxicity in a single covalent immunochemotherapeutic; (v) reduced innocent pharmaceutical exposure of normal tissues and healthy organ systems; (vi) prolongation of plasma pharmacokinetic profiles; and (vii) reduced burden on metabolizing pathways and excretion processes. Given these perspective, the covalent gemcitabine‐(5′‐phosphoramidate)‐[anti‐IGF‐1R] immunochemotherapeutic represents a potential molecular strategy for enhancing potency and effectiveness of a chemotherapeutic moiety relevant to the naturally low response rates and frequency of resistance detected in many neoplastic cell types that overexpress IGF‐1R trophic membrane receptors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors claim no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Illustrations and figures were generated by the author and principal investigator (Coyne) while analysis if experimental results were jointly performed by both authors (Coyne, Narayanan). Extramural funding support for procurement of chemotherapeutics, biologicals, reagents, materials, and supplies originated from residual indirect costs associated with a previously completed and unrelated research investigations. The principal investigator (Coyne) and co‐investigator (Narayanan) are or were employees of the Department of Basic Sciences in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Wise Center on the campus of Mississippi State University.

References