Priapism is defined as a prolonged erection in the absence of sexual desire. The name derives from the Greek god Priapus who had an erect penis very much associated with sexual desire (Figure 1). It is written that his parents were Zeus and Aphrodite. When Hera, the wife of Zeus, heard of the pregnancy she cursed the child, such that, when the boy was born with oversized genitals, he was rejected by Aphrodite. The boy was brought up by shepherds who noticed that wherever they took him flowers would bloom and animals would copulate furiously. He thus became a god of fertility.

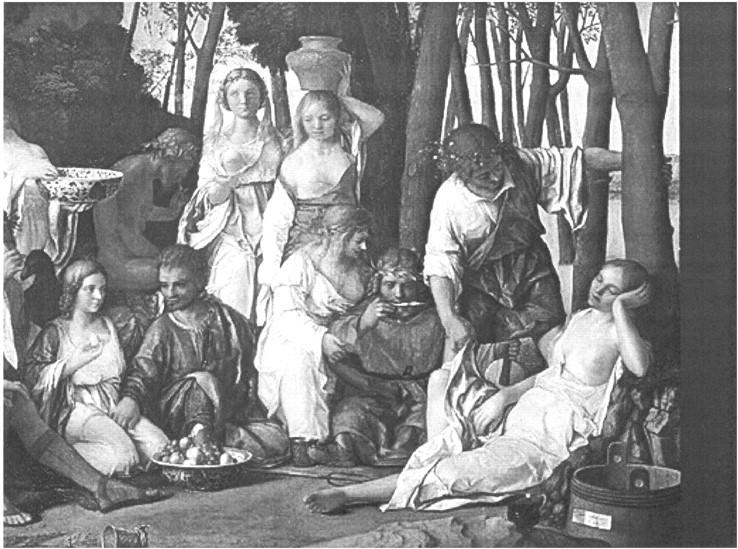

Figure 1.

The Feast of the Gods (detail). Giovanni Bellini and Titian 1514/1529. Priapus attempts to lift the skirt of the sleeping nymph Lotis. [National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC]

I have looked for references to priapism in works from the nineteenth century—a time when medicine began to benefit from scientific method and the formal recording of experience.1 The Wellcome Trust's (London) History of Medicine database was used to find case reports published on priapism in journals of the 19th century. The selection, as will be seen, was mainly British. In addition, textbooks from the urogenital section of the Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine were studied for recommendations on treatment of the condition. Ten case reports were discovered.2-11 The original journals for seven of these could be traced.2-8 Mention of the other three was made in textbooks and journals.9-11 All but two of the reports were published in the second half of the century.

DIAGNOSIS

The priapism reported by Mr Callaway in 1824 ‘occurred during and was not diminished by repeated connexion’.9 Likewise Mr Tripe describes a ‘stout seaman’ having ‘unusually fierce desire’ and an erection that persisted despite the fact that ‘congress was frequently resorted to’.2

Of the cases from the third quarter of the century, one was initiated by sexual intercourse, after which the gentleman experienced ‘passionate venereal desires’.3 In the other two cases, one in a ‘drunkard’,4 the other in a gentleman ‘not particular to his morals’,5 there does not seem to have been a precipitating incident.

Mr Hulke's patient, in 1888, was ‘drunk on cider’ when he had intercourse before development of priapism, although ‘neither he or his wife was aware of the occurrence of anything unusual in the sexual act’.6 One of the cases seen in the final quarter of the century was the result of ‘a hemorrhage’;7 and one from ‘excessive stimulation of this sexual centre’.10 The rest were all associated with leukaemia,7,8,11 although in one of these it was stated that ‘leukaemia could not have been in anyway the cause of the priapism’.7

TREATMENT

The treatment strategies described were threefold—localized medical and surgical therapies, systemic treatments such as emetics and bloodletting, and those specifically intended to sedate or temper sexual desire. Management was initially non-surgical in all but one case.7

There was until the end of the century no consensus as to whether the surgical or medical approach was superior. In 1824 Mr Callaway resorted to puncturing the left crus with a lancet, allowing ‘a large quantity of grumous blood be let out’, after 16 days of non-surgical management including venesection and leeching. Mr Tripe's sailor had likewise been bled and had had ‘twenty leeches applied to the perineum’ during his stay in the London Hospital. Before this he had had cold lotions and rhubarb applied to the penis, along with prescription of a tartar emetic, calomel and colocynth.

After failure of local and systemic treatments, again including leeches and potassium bromide, Dr Mackie found himself having to deal with urinary retention and paraphimosis. Believing that ‘surgical interference was the only means of procuring relief’ he incised the corpora: a large quantity of ‘semi-clotted venous blood came away’ and the bladder emptied. Mr Birkett is reported to have incised his patient reluctantly and only because of the persistent pain, afterwards declaring that this was a practice that he would not again adopt. Mr Hird's drunkard was treated with local belladonna as well as a purgative, calomel, colocynth, camphor and iodide of potassium; and the gentleman who had been drunk on cider likewise had his penis smeared with extract of belladonna and was given potassium bromide. Relief, however, was not achieved until a week later when ‘the above treatment was abandoned and continuous application of ice substituted for it’. The leukaemia patients did not appear to benefit from bromide of potassium which was used successfully by Dr Hargis. Dr Vorster's first case had an incision made ‘to relieve the paraphimosis that existed’. In the second case the priapism had been caused by ‘an accident’ and at operation a haematoma was found bulging forwards into the urethra. Vorster continues, ‘upon an incision being made into this tumour the priapism disappeared’.

OUTCOME

The first patient, treated surgically in 1824, ‘remained impotent for the rest of his life’. By contrast the patient treated conservatively in 1845 discharged himself from the London Hospital after 10 days and resumed his former abode ‘having free intercourse with the same female’. In the subsequent five months he spent time in Sydney having ‘erections, and complete communications’ such that on his return home he was considered ‘perfectly cured’.

Mr Birkett noted only these two previous reports, and despite his reservations about surgical intervention felt that his patient would have recovered in about a month after the extravasation of blood, had not suppuration arisen. Mr Hird declared after six weeks of medical management that ‘the penis is perfectly lax; no erection. The patient was discharged today cured’. Dr Mackie made no comments on the erections of his patient but had heard that he was in ‘perfect health’.

Mr Hulke's patient, who had benefited from ice treatment, was believed to have become ‘permanently incompetent for the sexual act’. One of Dr Vorster's patients was discharged ‘cured’ at seven weeks, but the leukaemia patients seem to have fared worse.

CLINICIANS' COMMENTS

With only two reports published before 1867, the conclusion by Mr Tripe that ‘the perfect recovery of the patient eventually [with conservative management] seems to show that any instrumental cure should not be attempted’ appears to have influenced successive clinicians. Several saw surgical intervention as at best a last resort.3,4,6 Mr Hird's patient was considered cured despite the fact that, when the patient ‘rubbed the point [he] could induce no erection by the experiment’. He considered that the condition was probably caused by nervous reflex irritation, since ‘incisions into the penis, to let out the extravasated blood have not been productive of any good result, whereas the administration of bromide of potassium has, in several instances, been followed by relief’. Mr Birkett, as already mentioned, ‘determined to treat the case on the principle adopted in all swellings resulting from extravasation of blood... to leave the repair to the efforts of nature and not to interfere with the process of absorption’. He also noted that Mr Tripe's sailor's progress towards recovery was ‘unassisted by surgical act’.

Dr Mackie discusses in detail differential diagnoses and states that ‘having set aside other rational causes of priapism, I was led by a diagnosis of exclusion to the structure of the corpus cavernosum, where... suspecting that effused blood was acting as a mechanical obstruction to the return circulation, I then made a free incision’. This logical approach, Mackie hoped, would prevent others from ‘unnecessary delay in having recourse to surgical interference’.

Mr Hulke makes no mention of Mackie's report but does go into the underlying pathophysiology, reporting that priapism ‘has been attributed to inflammation of the organ, to a local neurosis, obstruction of the erectile tissue by extravasated and coagulated blood’. With regard to his management strategy he writes that ‘the depressant and sedative medicines measures adopted when the man first entered hospital were prescribed on the first and second supposition, but they produced little or no effect, whereas the application of ice proved decidedly useful’. Concerning the underlying cause he continues, ‘owing to the maladroitness incidental to intoxication, the organ received a wrench... attended with extravasation of blood and inflammation’.

Dr Vorster's second, traumatic, case was thought to be caused by pressure of the haemorrhage causing ‘stagnation of venous blood in the corpora cavernosa’. With regard to leukaemia, Professor Kelti acknowledges that the priapism was related to ‘a constitutional disorder that needed other treatment than the administration of sedatives’.

TEXTBOOKS

Until the end of the century, journals were few and textbooks were perhaps more important in influencing medical behaviour. In his Function and Disorders of the Reproductive System William Acton describes how an erection ‘instead of being absent or imperfect may be only too persistent and too perfect’. He mentioned how it is a ‘terrible and humiliating condition’ and that very distressing instances are not infrequent among younger clergy who have ‘never given themselves up to self abuse’.12

Only towards the end of the century had sufficient been published on the condition to allow for a more objective review of the treatment.13,14 Henry Morris in 1895 recognized that ‘treatment is unsatisfactory’ and, in contrast to many of the clinicians cited above, seems to favour surgical management. He concludes, ‘tartar emetic, mercury, bromide of potassium, belladonna, leeches and strapping have all proved useless.... Incisions have been employed and deserve a further trial’.

Jacobson differs from previous authors in believing that ‘the condition is nearly unaccompanied with sexual desire’, but concedes that there may have been ‘excessive indulgence in, or an injury received during coitus, the patient in either case having been often drunk’. Possible pathological explanations for the association with leukaemia and injuries to the spinal cord are mentioned. Tartar emetic and mercury are rejected, although he writes ‘where the mischief dates to excessive stimulation of the sexual centre bromide of potassium may be expected to be useful’. He states, ‘mercury, belladonna, strapping and leeches have also all proved fruitless’. As regards the choice of surgical rather than medical treatment Jacobson comments, ‘whether an asceptic incision will, in future, give better results remains to be seen’. He goes on to acknowledge the successful use of such treatment by various authors5,7,9 and pays tribute to Dr Mackie for ‘a case very fully reported’.

DISCUSSION

Veno-occlusive or low-flow priapism is now considered a surgical emergency, penile aspiration being recommended within 6 hours to prevent permanent impotence.15 Clearly by the end of the nineteenth century, although there was evidence for the failure of conservative treatment and the success of surgical intervention in reducing the erection, the need for such urgent treatment had not been recognized. The associated conditions and underlying causes, however, had been well reported.13,14 As regards the medical therapies, many (such as leeching and administration of emetics) presumably had little reasoned scientific basis, but ice (especially as an enema) is still used today.16 Autonomic manipulation in the form of intracavernosal phenylephedrine or adrenaline is a current treatment,15 although we may doubt whether this was the logic behind application of belladonna.

It would appear that only at the very end of the century were lessons learnt from previous published reports, when the material was collated in textbooks. The bizarre case reported by Mr Tripe in 1845 may have influenced the treatment choices of successive practitioners. It is difficult to know what the exact diagnosis and pathogenesis was, since such longlasting priapism would usually result in impotence. It may be that the sailor had the rare high-flow priapism, due to a cavernosal artery rupture sustained as a result of his ‘unusually fierce desire’. Such an injury would not necessarily have caused ischaemic damage to the corpora and could have repaired itself spontaneously. The seemingly low regard of the surgeon for this patient is echoed in many of the reports, with the implied (and incorrect) association of priapism with drunkenness, low social status and lasciviousness.

As the nineteenth century approached its end, strategies based on ‘morality’ and defective reasoning began to make way for treatments reflecting cumulative experience and knowledge.

References

- 1.Porter R. Blood and Guts—a Short History of Medicine. London: Penguin, 2002

- 2.Tripe JW. Case of continued priapism. Lancet 1845;ii: 8 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkett J. Case in which persistent priapism was caused by extravasation of blood into the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Lancet 1867;i: 207-8 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hird. Case of priapism lasting six weeks; recovery. Lancet 1873;i: 90-1 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackie J. Notes of a case of persistent priapism. Edinb Med J 1873;18: 418-23 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hulke. A case of long continued priapism after coitus; remarks. Lancet 1888;i: 321 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vorster. The operative treatment of priapism. Lancet 1888;ii: 1144 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelti. A concomitant of leukaemia. BMJ 1883;2: 736 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaway T. London Medical Repository 1824: 286-7

- 10.Hargis. N Orleans J Med 1869:Jan

- 11.Salzer F. Ein Fall von langdauerndem Priapismus nebst Bemerkingen über die Beziehungen desselben zu Leukamie. Berlin Klin Woch 1879: 152-5

- 12.Acton W. Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs. 1862

- 13.Morris H. Injuries and Disease of the Genital and Urinary Organs. London: Cassell, 1895: 175

- 14.Jacobson WHA. The Diseases of the Male Organs of Generation. London: Churchill, 1893: 693-9

- 15.Anonymous. Priapism. In British National Formulary, Section 7.4.5. London: BMA/Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2003 [www.BNF.org]

- 16.McAninch JW. Disorders of the penis and male urethra. In: Tanagho E, McAninch JW, eds. Smith's General Urology. San Francisco: McGraw-Hill, 2000: 668-9