Abstract

The synthesis of acridanes and related compounds through a Cu‐catalysed radical cross‐dehydrogenative coupling of simple 2‐[2‐(arylamino)aryl]malonates is reported. This method can be further streamlined to a one‐pot protocol involving the in situ fomation of the 2‐[2‐(arylamino)aryl]malonate by α‐arylation of diethyl malonate with 2‐bromodiarylamines under Pd catalysis, followed by Cu‐catalysed cyclisation.

Keywords: Acridanes, Copper, Homogeneous catalysis, Nitrogen heterocycles, Cross‐coupling, Dehydrogenation, One‐pot reaction

Introduction

In recent years C–H activation has emerged as a powerful and attractive method in organic synthesis since it enables the formation of C–C bonds without pre‐functionalisation of one or both of the coupling partners, which leads to more efficient and atom‐economical processes. Within the wider pantheon of C–H activation, cross‐dehydrogenative couplings (CDC) have proved to be versatile procedures for the selective formation of C–C bonds from two different C–H systems under oxidative conditions.1 Our contribution in this area involves the synthesis of diverse nitrogen heterocycles through the Cu‐catalysed oxidative coupling of Csp2–H and Csp3–H bonds;2 a radical variant of the CDC process.

9,10‐Dihydroacridines (acridanes) have garnered much attention3 due to their potent biological activity, including inhibition of histone deacetylase (class IIa)4 and HIV reverse transcriptase,5 neuroleptic activity6 and as activators of K2P potassium channels7 (e.g., 1, Figure 1). Furthermore, acridanes have been employed as chemiluminescent sensors in immunoassays8 (e.g., 2), as NADH analogues in hydride‐transfer reactions,9 as host materials in OLEDs10 (e.g., 3), as photoswitches11 and as molecular motors.12 Moreover, acridanes are valuable building blocks that are readily oxidised to acridines or acridones,13 functionalised by C–H activation14 and easily converted into 5H‐dibenzo[b,f]azepines or 5,11‐dihydro‐10H‐dibenzo[b,e][1,4]diazepines by ring expansion.15

Figure 1.

Examples demonstrating the utility of acridanes.

Given the proven utility of acridanes, the sparse number of general methods available for their preparation is surprising.3 Traditionally, they have been prepared by nucleophilic addition to acridines 4 or acridinium salts 5 (Scheme 1, eq 1),16 or by a Friedel–Crafts‐type cyclisation of diarylamines 7 with strong acid (Scheme 1, eq 2).17 However, the need to rely either on the commercial availability or on a potentially lengthy synthesis of acridines 4, in combination with the requirements for the use of strong acids and well‐known problems of site selectivity associated with Friedel–Crafts cyclisations, means that new approaches to highly substituted acridane derivatives are of considerable interest.

Scheme 1.

Approaches for the synthesis of acridanes.

Thus, in continuation of our studies on the synthesis of diverse heterocyclic scaffolds by oxidative cyclisation of linear precursors with inexpensive Cu salts,2 our goal was to exploit this simple yet powerful methodology in the preparation of acridane derivatives 10 from 2‐[2‐(arylamino)aryl]malonates 9 (Scheme 1, eq 3).

The likely mechanism for this process, by analogy with earlier studies,[2d], [2f] is shown in Scheme 1. Initially, proton abstraction and single‐electron oxidation would give malonyl radical A, which would undergo intramolecular homolytic aromatic substitution to give B, followed by further oxidation to give the cyclohexadienyl cation C, which would finally aromatise to generate the desired product 10. Evidence for a radical‐based mechanism in these Cu‐mediated oxidative coupling reactions includes radical‐clock experiments,[2d] as well as DFT calculations conducted by Kündig in related systems.[2f] Clearly, two equivalents of Cu salt are nominally required to effect both single‐electron oxidations involved in the process. However, in related studies we have demonstrated that a catalytic amount of the Cu salt may be used with air serving as the terminal oxidant.

Results and Discussion

The initial task was to develop a flexible and modular approach for the synthesis of the cyclisation precursors 15 (Scheme 2), which would allow the facile introduction of substituents at various positions on the acridane skeleton.

Scheme 2.

Modular synthesis of cyclisation precursors 15a–j.

In the event, N‐aryloxindoles 11 proved to be versatile starting materials for the preparation of cyclisation precursors 15 by a three‐step protocol (Scheme 2). First, ring‐opening of the lactam moiety was carried out by treatment with NaOH in refluxing THF, followed by in situ formation of the dianions 12 by addition of nBuLi at low temperature and subsequent trapping with the appropriate electrophile to give carboxylic acids 13.18 Then, simple esterification, deprotonation with LiHMDS and trapping with the requisite cyano‐ or chloroformate delivered 2‐[2‐(arylamino)aryl]malonates 15a–j. In this manner, control over the substitution pattern on the aromatic rings, as well as on the nitrogen atom and ester, functionality could be readily achieved (14–63 % unoptimised overall yields; see the Supporting Information for details).

With ready access to the required linear substrates in hand, the cyclisation of model substrate 15a was then examined. Pleasingly, treatment of 15a under the conditions previously reported[2b] in our synthesis of oxindoles [Cu(2‐ethylhexanoate)2 (10 mol‐%), toluene, reflux, open flask] delivered the desired acridane 16a in 87 % yield without the need for further optimisation (Scheme 3). It is also noteworthy that the oxidative coupling could be performed in the presence of only 5 mol‐% or 2 mol‐% of the catalyst, with only a minor drop in yield (Scheme 3, footnote a).

Scheme 3.

Scope of the Cu‐catalysed synthesis of acridanes. [a] 16a was obtained in 83 and 84 % yield when Cu(2‐ethylhexanoate)2 (5 mol‐% and 2 mol‐%) were used, respectively. [b] Cu(2‐ethylhexanoate)2 (2.5 equiv.) and DIPEA (2.5 equiv.) were used under an atmosphere of argon.

By following this successful initial result, the generality of this new Cu‐catalysed approach to acridanes was explored (Scheme 3). First, cyclisation of 15b, which bears a removable protecting group on the nitrogen atom, was carried out to give N‐benzylacridane 16b, albeit in reduced yield in comparison to N‐ethyl derivative 16a. Next, acridanes 16c–f bearing differentially protected esters (e.g., allyl, Bn, Fmoc) were prepared, which opens the possibility for further manipulations of the cyclised products (vide infra). The Fmoc‐protected ester 16e was crystalline, which allowed unambiguous confirmation of its structure through X‐ray crystallographic analysis (see the Supporting Information).

Next, the introduction of substituents at various positions on either aromatic ring of the acridane skeleton was explored, which gave 16g–j in good to excellent yields. Incorporation of a nitrogen atom into one of the aromatic rings was also possible; isolation of the corresponding aza‐acridane 16k was achieved in 66 % yield.

Having established the effectiveness of the Cu‐catalysed route to acridanes 16a–k, we extended this method to the synthesis of other related heterocycles of interest, such as xanthenes and thioxanthenes (Scheme 3, 16l–m). However, cyclisation of a linear diaryl ether in the presence of 10 mol‐% Cu(2‐ethylhexanoate)2 under the standard reaction conditions delivered xanthene 16l in a disappointing yield of 33 %. Also isolated was an equal amount of a by‐product, identified as ethyl 2‐oxo‐2‐(2‐phenoxyphenyl)acetate, which arises from competing decarboxylation and aerial oxidation of the starting material. This problem was exacerbated in the case of thioxanthene 16m, which was isolated in only 20 % yield along with 53 % of the undesired by‐product. Further optimisation of these reactions is clearly required but fortunately, in both cases, the yield of the oxidation by‐products could be minimised by performing the cyclisation under an atmosphere of argon, which leads to formation of xanthene 16l and thioxanthene 16m in 47 and 44 % yields, respectively. While formation of the desired products 16l–m is enhanced under these conditions, performing the reaction under argon necessitates the use of 2.5 equiv. of Cu salt to allow the reaction to proceed to completion (see proposed mechanism, Scheme 1).

In order to demonstrate the utility of the acridanes derived from the Cu‐catalysed cyclisation, a brief study on their further functionalisation was carried out (Scheme 4). For example, treatment of 16a with an excess of KOH in EtOH/H2O resulted in saponification and decarboxylation to give acid 17 in excellent yield. This provides an alternative route, which may be useful in the synthesis of chemiluminescent sensors analogous to 2 (Figure 1). Reduction of the esters was also achieved in the presence of LiAlH4 to give diol 18 in 94 % yield. Furthermore, selective functionalisation of the allyl ester in 16c was carried out by decarboxylative allylic alkylation in the presence of 4 mol‐% Pd(PPh3)4 to give 19 and thereby generate a new quaternary carbon centre, again in excellent yield. Finally, hydrogenolysis of the benzyl protecting group in 16b delivered acridane 20 bearing a free N–H group in reasonable, un‐optimised yield.

Scheme 4.

Further derivatisation of acridanes obtained from oxidative coupling.

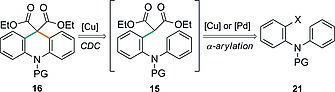

As a final aspect to this work, we explored the potential of an expedited, one‐pot approach to acridanes 16 based on the α‐arylation of 1,3‐dicarbonyl compounds with haloarenes 21 to generate intermediates 15 in situ, which would then undergo the oxidative coupling reaction (Scheme 5). Given the well‐known ability of Cu salts to catalyse both processes,19 a highly efficient transformation seemed attainable.

Scheme 5.

Retrosynthesis of acridanes 16 through a one‐pot α‐arylation–cyclisation process.

The requisite 2‐halodiarylamines 21 were easily prepared by the addition of commercially available 2‐haloanilines 22 to benzynes, which were prepared in situ from 2‐(trimethylsilyl)phenyl triflates 23 in the presence of CsF, and subsequent N‐alkylation (Scheme 6; see the Supporting Information for more details).20

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of 2‐halodiarylamines 21a–d.

Next, the crucial transition‐metal‐catalysed α‐arylation reaction between diethyl malonate and 2‐halodiarylamines 21a–b was examined; selected results are shown in Table 1. In the event, none of the desired α‐arylation products was observed on heating either 2‐iodo‐ or 2‐bromo‐N‐methyl‐N‐phenylaniline 21a–b with diethyl malonate in the presence of CuI and 2‐picolinic acid[19a] (Table 1, entries 1–2). Similarly, other Cu‐based catalyst systems, which are reported for the coupling of dialkyl malonates with simple haloarenes, proved equally ineffective (results not shown). Thus, attention turned to the use of palladium catalysts to effect the initial transformation.

Table 1.

Optimisation of the α‐arylation of 21a–b with diethyl malonate

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | X | Conditions | Yield [%] |

| 1 | I | CuI (10 mol‐%), 2‐picolinic acid (20 mol‐%) | –a |

| Cs2CO3 (3 equiv.), dioxane, reflux, 17 h | |||

| 2 | Br | CuI (10 mol‐%), 2‐picolinic acid (20 mol‐%) | –a |

| Cs2CO3 (3 equiv.), dioxane, reflux, 17 h | |||

| 3 | I | Pd(OAc)2 (2 mol‐%), tBuMePhos (4.4 mol‐%) | –a |

| K3PO4 (2.4 equiv.), toluene, reflux, 18 h | |||

| 4 | Br | Pd(OAc)2 (2 mol‐%), tBuMePhos (4.4 mol‐%) | –a |

| K3PO4 (2.4 equiv.), toluene, reflux, 18 h | |||

| 5 | I | Pd2dba3 ·CHCl3 (1 mol‐%), tBu3P·HBF4 (4 mol‐%) | 32 |

| K3PO4 (3 equiv.), toluene, 70 °C, 15 h | |||

| 6 | I | Pd2dba3 ·CHCl3 (1 mol‐%), tBu3P·HBF4 (4 mol‐%) | 61 |

| K3PO4 (3 equiv.), toluene, reflux, 14 h | |||

| 7 | Br | Pd2dba3·CHCl3 (1 mol‐%), tBu3P·HBF4 (4 mol‐%) | 72 |

| K3PO4 (3 equiv.), toluene, reflux, 17 h | |||

Starting materials only were observed by 1H NMR analysis of the unpurified reaction mixture.

No α‐arylation was observed when using the Pd(OAc)2/tBuMePhos catalyst system developed by Buchwald (Table 1, entries 3–4),21 but an encouraging yield of 32 % was obtained for 15n by switching to Pd2dba3 ·CHCl3 (1 mol‐%) as the catalyst with the bench stable ligand tBu3P·HBF4 (4 mol‐%) in toluene at 70 °C (Table 1, entry 5).22 Increasing the reaction temperature allowed us to isolate 2‐[2‐(arylamino)aryl]malonate 15n in 61 % (from 21a) and 72 % (from 21b) yields, respectively.

With conditions for the malonate coupling in hand, our attention then turned to establishing the one‐pot α‐arylation–cyclisation protocol to prepare acridanes directly (Scheme 7). To this end, the Pd‐catalysed α‐arylation reaction between 2‐bromo‐N‐methyl‐N‐phenylaniline 21b and diethyl malonate was first carried out by using the optimised conditions described above under an atmosphere of argon. Subsequently, the reaction flask was simply opened to the air, Cu(2‐ethylhexanoate)2 (15 mol‐%) was added and heating continued for a further 24 h to facilitate the cyclisation. In this manner, the target acridane 16n was isolated in a pleasing yield of 74 % over the 2 steps. Furthermore, substituents could be readily introduced on one or both of the aromatic rings, which allows access to more highly substituted acridanes such as 16o and 16p.

Scheme 7.

Scope of the one‐pot α‐arylation–cyclisation approach to acridanes.

Conclusions

In summary, we report a Cu‐catalysed radical cross‐dehydrogenative‐coupling approach to acridanes and related heterocycles from readily available 2‐[2‐(arylamino)aryl]malonates. This highly atom‐economical method uses inexpensive Cu(2‐ethylhexanoate)2 as the catalyst under mild conditions and thus avoids many of the problems associated with classical strategies for the synthesis of acridanes. The diester moiety resulting from the oxidative coupling reaction serves as a useful handle for further functionalisation. In addition, we have established a streamlined protocol involving the in situ formation of the cyclisation precursor by the α‐arylation of diethyl malonate with a 2‐bromodiarylamine under Pd catalysis, followed by subsequent Cu‐catalysed cyclisation to give the acridanes in a one‐pot fashion. Further studies will be carried out to utilise this new method in target synthesis.

Experimental Section

Representative Procedure for the Cu‐catalysed Synthesis of Acridanes: To a solution of the cyclisation precursor 15 (1.00 mmol) in toluene (10 mL) was added Cu(2‐ethylhexanoate)2 (35.0 mg, 0.100 mmol). The reaction mixture was heated to reflux (oil bath at 120 °C) for 17 h with the condenser left open to the air. After cooling to room temp., saturated NH4Cl soln (25 mL) was added, and the aqueous phase extracted with EtOAc (3 × 25 mL). The combined organics were washed with NH4OH soln (10 %, 25 mL), dried with MgSO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash column chromatography with EtOAc/hexane as eluent afforded the title compound 16 (see the Supporting Information for details).

CCDC 1498037 (for 16e) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council for postdoctoral funding (T. E. H.; EP/J000124/1) and Dr A. C. Whitwood (University of York) for assistance with X‐ray crystallography.

Contributor Information

Timothy E. Hurst, Email: hurstt@queensu.ca

Richard J. K. Taylor, Email: richard.taylor@york.ac.uk, http://www.york.ac.uk/chemistry/staff/academic/t‐z/rtaylor/

References

- 1.a) Girard S. A., Knauber T. and Li C.‐J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2014, 53, 74–100; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem., 2014, 126, 76; [Google Scholar]; b) Li C.‐J., Acc. Chem. Res., 2009, 42, 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Drouhin P. and Taylor R. J. K., Eur. J. Org. Chem., 2015, 2333–2336; [Google Scholar]; b) Hurst T. E., Gorman R. M., Drouhin P., Perry A. and Taylor R. J. K., Chem. Eur. J., 2014, 20, 14063–14073; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Klein J. E. M. N., Perry A., Pugh D. S. and Taylor R. J. K., Org. Lett., 2010, 12, 3446–3449; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Perry A. and Taylor R. J. K., Chem. Commun., 2009, 3249–3251; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Jia Y.‐X. and Kündig E. P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2009, 48, 1636–1639; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem., 2009, 121, 1664; [Google Scholar]; f) Dey C., Larionova E. and Kündig E. P., Org. Biomol. Chem., 2013, 11, 6734–6743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For a recent review of acridines and their derivatives, see: Schmidt A. and Liu M., Adv. Heterocycl. Chem., 2015, 115, 287–353. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tessier P., Smil D. V., Wahhab A., Leit S., Rahil J., Li Z., Déziel R. and Besterman J. M., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2009, 19, 5684–5688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson B. L., Patel M., Rodgers J. D., Tarby C. M., R. Bakthavatchalam US6593337B1, 2003.

- 6. Kaiser C., Fowler P. J., Tedeschi D. H., Lester B. M., Garvey E., Zirkle C. L., Nodiff E. A. and Saggiomo A. J., J. Med. Chem., 1974, 17, 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bagriantsev S. N., Ang K.‐H., Gallardo‐Godoy A., Clark K. A., Arkin M. R., Renslo A. R. and Minor D. L. Jr, ACS Chem. Biol., 2013, 8, 1841–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Akhavan‐Tafti H., DeSilva R., Arghavani Z., Eickholt R. A., Handley R. S., Schoenfelner B. A., Sugioka K., Sugioka Y. and Schaap A. P., J. Org. Chem., 1998, 63, 930–937; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Akhavan‐Tafti H., DeSilva R., Eickholt R., Handley R., Mazelis M. and Sandison M., Talanta, 2003, 60, 345–354; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Di Fusco M., Quintavalla A., Lombardo M., Guardigli M., Mirasoli M., Trombini C. and Roda A., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 1567–1576, and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Dhuri S. N., Lee Y.‐M., Sook Seo M., Cho J., Narulkar D. D., Fukuzumi S. and Nam W., Dalton Trans., 2015, 44, 7634–7642; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Han Y., Lee Y.‐M., Mariappan M., Fukuzumi S. and Nam W., Chem. Commun., 2010, 46, 8160–8162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Méhes G., Nomura H., Zhang Q., Nakagawa T. and Adachi C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51, 11311–11315; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem., 2012, 124, 11473; [Google Scholar]; b) Ding L., Dong S.‐C., Jiang Z.‐Q., Chen H. and Liao L.‐S., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2015, 25, 645–650 and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raskosova A., Stößer R. and Abraham W., Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 3964–3966, and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Kulago A. A., Mes E. M., Klok M., Meetsma A., Brouwer A. M. and Feringa B. L., J. Org. Chem., 2010, 75, 666–679; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vetter A. and Abraham W., Org. Biomol. Chem., 2010, 8, 4666–4681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Jawale D. V., Gravel E., Shah N., Dauvois V., Li H., Namboothiri I. N. N. and Doris E., Chem. Eur. J., 2015, 21, 7039–7042; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang B., Cuia Y. and Jiao N., Chem. Commun., 2012, 48, 4498–4500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Pandey G., Jadhav D., Tiwari S. K. and Singh B., Adv. Synth. Catal., 2014, 356, 2813–2818; [Google Scholar]; b) Pintér Á. and Klussmann M., Adv. Synth. Catal., 2012, 354, 701–711. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Stopka T., Marzo L., Zurro M., Janich S., Würthwein E.‐U., Daniliuc C. G., Alemán J. and Mancheño O. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2015, 54, 5049–5053; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem., 2015, 127, 5137; [Google Scholar]; b) Cho H., Iwama Y., Okano K. and Tokuyama H., Chem. Pharm. Bull., 2014, 62, 354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For lead references, see ref 4 and: a) Takeda T., Uchimura Y., Kawai H., Katoono R., Fujiwarab K. and Suzuki T., Chem. Commun., 2014, 50, 3924–3927; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Natrajan A. and Wen D., Green Chem. Lett. Rev., 2013, 6, 237–248; [Google Scholar]; c) Hernán‐Gómez A., Herd E., Uzelac M., Cadenbach T., Kennedy A. R., Borilovic I., Aromí G. and Hevia E., Organometallics, 2015, 34, 2614–2623; [Google Scholar]; d) Liang T., Xiao J., Xiong Z. and Li X., J. Org. Chem., 2012, 77, 3583–3588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For lead references, see: a) Han X.‐D., Zhao Y.‐L., Meng J., Ren C.‐Q. and Liu Q., J. Org. Chem., 2012, 77, 5173–5178; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Andrew T. L. and Swager T. M., J. Org. Chem., 2011, 76, 2976–2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fuenfschilling P. C., Zaugg W., Beutler U., Kaufmann D., Lohse O., Mutz J.‐P., Onken U., Reber J.‐L. and Shenton D., Org. Process Res. Dev., 2005, 9, 272–277. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Yip S. F., Cheung H. Y., Zhou Z. and Kwong F. Y., Org. Lett., 2007, 9, 3469–3472; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xie X., Cai G. and Ma D., Org. Lett., 2005, 7, 4693–4695; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cristau H.‐J., Cellier P. P., Spindler J.‐F. and Taillefer M., Chem. Eur. J., 2004, 10, 5607–5622; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hennessy E. J. and Buchwald S. L., Org. Lett., 2002, 4, 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Z. and Larock R. C., J. Org. Chem., 2006, 71, 3198–3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fox J. M., Huang X., Chieffi A. and Buchwald S. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2000, 122, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oda K., Akita M., Hiroto S. and Shinokubo H., Org. Lett., 2014, 16, 1818–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information