Abstract

Background

the first quality of life questionnaire specific to sarcopenia, the SarQoL®, has recently been developed and validated in French. To extend the availability and utilisation of this questionnaire, its translation and validation in other languages is necessary.

Objective

the purpose of this study was therefore to translate the SarQoL® into English and validate the psychometric properties of this new version.

Design

cross-sectional.

Setting

Hertfordshire, UK.

Subjects

in total, 404 participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study, UK.

Methods

the translation part was articulated in five stages: (i) two initial translations from French to English; (ii) synthesis of the two translations; (iii) backward translations; (iv) expert committee to compare the backward translations with the original questionnaire and (v) pre-test. To validate the English SarQoL®, we assessed its validity (discriminative power, construct validity), reliability (internal consistency, test–retest reliability) and floor/ceiling effects.

Results

the SarQoL® questionnaire was translated without any major difficulties. Results indicated a good discriminative power (lower score of quality of life for sarcopenic subjects, P = 0.01), high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88), consistent construct validity (high correlations found with domains related to mobility, usual activities, vitality, physical function and low correlations with domains related to anxiety, self-care, mental health and social problems) and excellent test– retest reliability (intraclass coefficient correlation of 0.95, 95%CI 0.92–0.97). Moreover, no floor/ceiling has been found.

Conclusions

a valid SarQoL® English questionnaire is now available and can be used with confidence to better assess the disease burden associated with sarcopenia. It could also be used as a treatment outcome indicator in research.

Keywords: older people, sarcopenia, quality of life, translation, validation

Introduction

Sarcopenia is a syndrome characterised by progressive and generalised loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength with a risk of adverse outcomes such as physical disability, functional decline, depression, falls and death [1–13]. Until now, the consequences of sarcopenia on quality of life have been poorly investigated and poorly understood. While there is no consensus over how to measure and monitor health-related quality of life (HRQoL), the most commonly adopted method defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns [14]. Evaluating the impact of sarcopenia on individuals’ HRQoL with a disease-specific tool is important to better detect effect of treatment and observe longitudinal changes of quality of life in subjects suffering from sarcopenia [15]. Until recently, there were no validated specific patient-based instruments for measuring quality of life in those with sarcopenia [16]. Based on these findings, Beaudart et al. [17, 18] developed and validated, in 2015, the SarQoL® (Sarcopenia and Quality of Life, www.sarqol.org), a quality of life questionnaire specific for those diagnosed with sarcopenia composed of 22 questions that can provide more accurate knowledge regarding the impact of sarcopenia on subjects’ well-being. The SarQoL® has been developed and validated in French. To extend the availability and utilisation of this questionnaire, its translation and validation in other languages is necessary. The purpose of this study was therefore to translate the SarQoL® questionnaire into English and investigate its main psychometric properties.

Methods

The SarQoL®

The SarQoL® is composed of 22 questions including in total 55 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (Appendix 1, also available on www.sarqol.org; Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online). The questionnaire is scored, through a scoring algorithm, on 100 points, with higher scores reflecting a better quality of life. Items are organised into seven domains of HRQoL: domain 1 “Physical and Mental Health”; domain 2 “Locomotion”; domain 3 “Body Composition”; domain 4 “Functionality”; domain 5 “Activities of daily living”, domain 6 “Leisure activities” and domain 7 “Fears”. The SarQoL® is a self-administrated questionnaire and can be completed in approximately 10 min.

Participants

The study sample composed of men and women from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS) who agreed to participate in the UK component of the European Project on Osteoarthritis (EPOSA). The HCS and EPOSA study have been described in detail previously [19, 20]. Briefly, in conjunction with the National Health Service Central Registry and the Hertfordshire Family Health Service Association, men and women who were born as singleton births between 1931 and 1939 in Hertfordshire and still lived in the country during the period 1998–2003 were traced. Among them, 592 HCS participants were eligible to participate in EPOSA which started in 2011, of whom 444 (75%) provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The mean age of these 222 women and 222 men was 75.2 (2.6) years. They presented a mean body mass index of 28.1 ± 4.6 kg/m2 and 20.9% of them presented two or more chronic diseases. All demographic, health, social and psychological characteristics have been fully described previously [20].

Procedures

English translation of the SarQoL®

The translation was performed according to translation guidelines [2]. Five different phases were followed: (i) the initial translation from French to English by two independent bilingual translators which were English native speakers; (ii) the synthesis of the first two translations to provide a single “version 1” of the translated questionnaire; (iii) the backward translation by two independent bilingual blinded to the original French version and having French as their first language; (iv) an expert committee review to compare the backward translations with the original questionnaire and consent on a “version 2” of the translated questionnaire; (v) the pre-test of the “version 2” of the SarQoL® to ensure good comprehension of each question of the questionnaire and conclude with the “version 3”, final version of the English SarQoL®.

Psychometric validation of the English version of the SarQoL®

The methodology applied for the validation of the French version of the SarQoL® was followed and completed in two steps. All of the analyses described below were performed using IMB SPPS Statistics 21.0. Results were considered statistically significant at the 5% critical level (P < 0.05).

-

(1)

In the first step, the SarQoL® questionnaire was sent to the whole sample of participants in order to assess the discriminative power of the SarQoL®, its internal consistency and the presence of floor and ceiling effects.

-

(A)

Discriminative power For the discriminative power of the questionnaire, it was assumed that QoL is better in subjects without a diagnosis of sarcopenia compared to subjects diagnosed sarcopenic. We used the definition of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) for the diagnosis of sarcopenia [9]. The EWGSOP recommends using the presence of both low muscle mass and low muscle function (strength or performance) for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Therefore, a body composition dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan (Hologic Discovery) was performed on participants for assessment of lean mass, a handgrip dynamometer was used for the assessment of muscle strength and gait speed on a 8-feet distance was measured for the assessment of physical performance. An independent sample T-test was performed to assess the difference of overall and domain QoL scores between the sarcopenic subjects and the non-sarcopenic subjects.

-

(B)

Internal consistency Internal consistency is the estimation of the questionnaire homogeneity. To measure internal consistency, we used Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A coefficient value greater than 0.70 indicates a high level of internal consistency [21]. The impact of each domain on the reliability was also considered. Normality of quantitative variables was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since scores from the SarQoL® questionnaire were normally distributed, the correlation of each domain with the total score of the SarQoL® was also assessed using Pearson’s correlations.

-

(C)

Floor and ceiling effects Floor and ceiling effects were defined when a high percentage of the population had the lowest or the highest score, respectively. Floor and ceiling effects higher than 15% were considered to be significant [22].

-

(A)

-

(2)

In a second step, the construct validity and the test– retest reliability of the SarQoL® was determined. These analyses should ideally be performed on subjects with sarcopenia. However, when using the definition of the EWGSOP [9] to identify sarcopenic subjects in the sample, only a restricted number of sarcopenic subjects (n = 14) were identified. This small sample was insufficient to achieve the recommendations; at least 50 subjects are necessary for these validation analyses [22]. Therefore, modified cut-offs from those proposed by the EWGSOP were used to define a larger group of subjects, not with sarcopenia itself, but with a low global “muscle function”. The participants were selected by applying the following formula: lowest sex-specific half of appendicular muscle mass + (lowest sex-specific half of muscle strength or lowest half gait speed). With this method, 93 subjects were identified with low “muscle function”. The 93 participants received an envelope containing twice the SarQoL® questionnaire (SarQoL® 1 and SarQoL® 2) as well as the generic Short Form-36 questionnaire [23] and the the EuroQoL 5-dimension (EQ-5D) questionnaire [24]. They completed first one SarQoL® as well as the SF-36 and the EQ-5D questionnaires, for the measurement of the construct validity, and were invited to respect a 2-week interval before completing the second SarQoL®, for the measurement of test–retest reliability.

-

(A)

Construct validity The construct validity was investigated by measuring using the convergent and divergent validity. The correlation between the SarQoL® and other questionnaires or domains of questionnaires which were supposed to have similar dimension (convergent validity) or different dimension (divergent validity) was assessed. Therefore, beside completing the SarQoL®, the participants were also asked to complete the SF-36 questionnaire [23] which is composed of 36 items measuring 8 HRQoL domains (physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problem and mental health). Additionally participants were also asked to complete the EQ-5D questionnaire [24] which records the level of self-reported problems according to five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), with each dimension having three levels: no problems, some problems and extreme problems. Data of the SF-36 and the EQ-5D questionnaires were not normally distributed and we used therefore Spearman’s correlations to measure to correlation of the total score of the SarQoL® with the different scales of the SF-36 questionnaire as well as with the utility score of the EQ-5D questionnaire and the individual domains of the EQ-5D questionnaire.

-

(B)

Test–retest reliability The intraclass coefficient correlation (ICC) was used to test the reliability between the first and second questionnaires overall and individual domain scores of the SarQoL®. An ICC over 0.7 was considered as an acceptable reliability [22]. All participants were questioned about having any health change during the past 2 weeks. The results of the participants who did not report any health difference over this 2-week interval were used in analysis.

-

(A)

Results

Translation

The 22 questions of the SarQoL® questionnaire were translated without any major difficulties. Some discussions were however encountered regarding the choice of responses displayed for the 4-likert scale. A pre-test was performed on 10 subjects. Minor changes were consequently made to the questionnaire “version 2”. These changes, which did not modify the meaning of the sentences, were mainly related to choice of words used for the 4-Likert scale choices.

Psychometric quality analyses

-

(1)

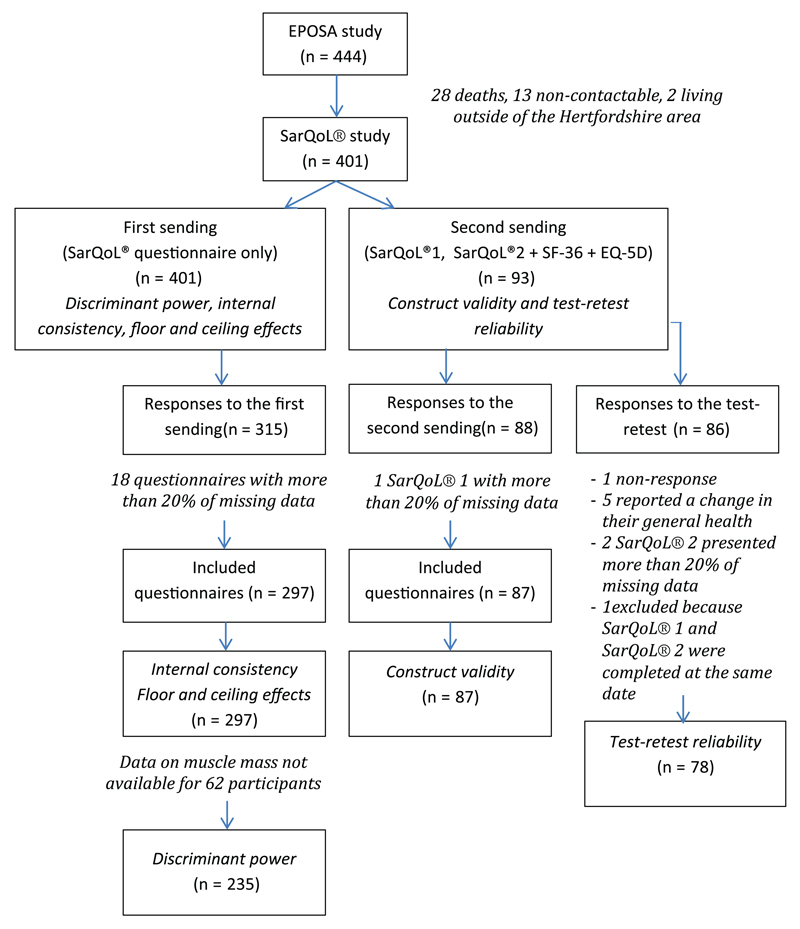

In the first step, the SarQoL® was sent to a sample of 401 participants of the EPOSA. A total of 315 participants completed the questionnaire; 18 questionnaires (5.7%) comprised more than 20% of missing data and were excluded from analyses. Therefore, 297 questionnaires were used (Figure 1). The population sample was composed of 297 subjects, 137 women (46.1%) and 160 men (53.9%) with a mean age of 79.5 ± 2.62 years.

-

(A)

Discriminant validity Data on muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance were only available for 235 of the 297 respondents. With the criteria and the cut-offs proposed by the EWGSOP [9], a total of 14 subjects were diagnosed sarcopenic. Sarcopenic subjects reported a reduced global quality of life compared to non-sarcopenic subjects (61.9 ± 16.5 versus 71.3 ± 12.8, P = 0.01). The domains of physical and mental health, locomotion, functionality and activities of daily living were also lower scored in sarcopenic subjects compared to non-sarcopenic ones (Table 1).

-

(B)

Internal consistency A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 was calculated indicating a high internal consistency. Deleting the domains one at the time, led to Chronbach’s alpha values varying between 0.84 (when deleting the domain 5 “Activities of daily living”) and 0.89 (for the domain 6 “Leisure activities”). Moreover, all domains showed a significant positive correlation with the total score of the SarQoL® ranging from r = 0.51, P < 0.001 (domain 6 versus total score of the SarQoL®) to 0.92, P < 0.001 (domain 4 versus total score of the SarQoL®) (Table 2).

-

(C)

Floor and ceiling effects No subjects presented with the lowest score to the questionnaire (0 point) or the maximal score (100 points). Therefore, no floor neither ceiling effects were found for the questionnaire.

-

(A)

-

(2)

In a second step, the SarQoL® was sent to the 93 participants identified as having a low muscle function. A total of 88 questionnaires were completed. One of the questionnaires comprised more than 20% of missing data and was excluded from analyses. Therefore, construct validity analyses were performed on 87 questionnaires. For test–retest reliability, 78 questionnaires were used for the test–retest reliability analysis (Figure 1).

-

(A)

Construct validity Results of construct validity are available in Table 2. As expected, strong/good correlations were found between the SarQoL® and some domains of the SF-36 questionnaire which were supposed to have similar dimensions such as physical functioning (r = 0.82, P < 0.001), vitality (r = 0.74, P < 0.001) and role limitation due to physical problems (r = 0.54, P < 0.001) as well as with the utility score of the EQ-5D questionnaire (r = 0.58, P < 0.001) and the questions of the EQ-5D questionnaire related to mobility (r = −0.56, P < 0.001) and usual activities (r = −0.55, P < 0.001). We found weaker correlations between domains of the SarQoL® which were supposed to have different dimensions such as the domain of mental health (r = 0.29, P = 0.007), and the domain of role limitation due to social problems of the SF-36 questionnaire (r = 0.22, P = 0.04), the questions related to self-care of the EQ-5D questionnaire (r = −0.24, P = 0.032) and the questions related to anxiety of the EQ-5D questionnaire estionnaire, the (r = −0.32, P = 0.004).

-

(B)

Test–retest reliability Excellent agreement was found between the test and the retest with an ICC of 0.95 (95% CI 0.92–0.97). For individual domains, the lowest ICC was found for domain 6 (ICC of 0.78, 95%CI 0.58–0.88) which is however still considered as acceptable.

-

(A)

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the validation study of the English version of the SarQoL®. SarQoL®1 refers to the first SarQoL® used for the “test” and SarQoL®2 refers to the second SarQoL® used for the retest.

Table 1.

Discriminative power of the SarQoL®

| Sarcopenia (n = 14), mean ± SD |

No sarcopenia (n = 221), mean ± SD |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 61.9 ± 16.5 | 71.3 ± 12.8 | 0.01 |

| D1 Physical and Mental Health | 60.9 ± 15.5 | 71.1 ± 13.9 | 0.01 |

| D2 Locomotion | 57.1 ± 14.9 | 65.9 ± 15.9 | 0.04 |

| D3 Body Composition | 70.4 ± 14.9 | 71.9 ± 13.3 | 0.70 |

| D4 Functionality | 68.0 ± 18.7 | 76.5 ± 14.1 | 0.03 |

| D5 Activities of daily living | 55.9 ± 25.7 | 70.6 ± 13.3 | 0.002 |

| D6 Leisure activities | 43.9 ± 16.8 | 45.1 ± 18.6 | 0.81 |

| D7 Fears | 88.4 ± 12.5 | 91.3 ± 12.1 | 0.39 |

Table 2.

Correlations of the total score of the SarQoL® questionnaire with individual domains of the SarQoL®, the SF-36 questionnaire and the EQ-5D questionnaire

| Total score of the SarQoL, r |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| SarQoL D1 Physical and Mental Health | 0.84a | <0.001 |

| SarQoL D2 Locomotion | 0.85a | <0.001 |

| SarQoL D3 Body Composition | 0.61a | <0.001 |

| SarQoL D4 Functionality | 0.92a | <0.001 |

| SarQoL D5 Activities of daily living | 0.94a | <0.001 |

| SarQoL D6 Leisure activities | 0.51a | <0.001 |

| SarQoL D7 Fears | 0.54a | <0.001 |

| Convergent validity | ||

| SF-36 physical functioning | 0.82b | <0.001 |

| SF-36 role limitation due to physical problems | 0.54b | <0.001 |

| SF-36 bodily pain | 0.55b | <0.001 |

| SF-36 general health | 0.49b | <0.001 |

| SF-36 vitality | 0.74b | <0.001 |

| EQ-5D utility score | 0.58b | <0.001 |

| EQ-5D mobility | −0.56b | <0.001 |

| EQ-5D usual activities | −0.55b | <0.001 |

| Divergent validity | ||

| SF-36 social functioning | 0.47b | <0.001 |

| SF-36 role limitation due to emotional problem | 0.22b | 0.04 |

| SF-36 mental health | 0.29b | 0.007 |

| EQ-5D, self-care | −0.24b | 0.032 |

| EQ-5D pain/discomfort | −0.41b | <0.001 |

| EQ-5D anxiety/depression | −0.32b | 0.004 |

Pearson’s correlations (scores of the SarQoL® questionnaire normally distributed).

Spearman’s correlations (data of the SF-36 and the EQ-5D questionnaires not normally distributed).

Discussion

The SarQoL® is the first developed quality of life questionnaire specific to sarcopenia. Because the SarQoL® has only been developed and validated in French, this study aimed to provide an English version of the SarQoL® questionnaire, validated to be used for research and clinic in English-speaking countries. This research has produced an English version of the SarQoL® which, after transcultural adaptation and validation has proven to be a discriminant, valid and reliable tool to assess quality of life in subjects with sarcopenia.

To provide equivalence between the French and the English version of the SarQoL®, a rigorous translation and cross-cultural adaptation processes was followed. Proof of correctness and equivalence between the two questionnaires was provided by the high internal consistency of the translated questionnaire, by its consistent construct validity and the excellent test–retest reliability observed in results.

The psychometric properties analyses showed that the English version of the questionnaire is able to discriminate the sarcopenic subjects from the non-sarcopenic subjects. General quality of life seems better for the HCS participants compared to the Belgian population (54.7 (45.9–66.3) for the total score of the SarQoL® for Belgian sarcopenic individuals compared to 61.9 ± 16.5 for the HCS population). But in both cases, quality of life of sarcopenic subjects was lower than non-sarcopenic subjects. It has to be pointed that, during the development of the SarQoL® questionnaire, only questions related to sarcopenia have been included. Because each question is related to sarcopenia, it is therefore not surprising to find a lower quality of life for sarcopenic subjects. The English SarQoL® has also been shown to have a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88) which is identical to the French version. Moreover, it appears that the deletion of one domain at a time did not have a particular impact on the reliability. The construct validity analyses have also showed that the SarQoL® questionnaire was strongly and significantly correlated with some domains of quality of life which were supposed to have similar dimension, such as mobility, usual activities, vitality, physical functioning and finally physical problems. Because the SarQoL® contains questions specific to sarcopenia and then related to muscle function, these results were expected and can confirm the convergent validity of the SarQoL®. Moreover, we also found low correlations between the SarQoL® and some dimensions such as self-care, anxiety, mental health and social problems, which can confirm that the SarQoL® is divergent with domains that are supposed to be divergent. Finally, the test–retest reliability has been found to be excellent, both for the total score (0.95 (95% CI 0.92–0.97), which is more or less similar to the French version 0.91 (95% CI 0.82–0.95)) and for the individual domains of the SarQoL®. The SarQoL® seems to be stable across time when no health changes occurred.

This study has some limitations. First of all, our sample only comprises 14 sarcopenic subjects which led to alterations to our validation analyses. For the question of feasibility, modified cut-offs for the EWGSOP definition were used to define a larger group of subjects with impaired muscle function. Therefore, this population does not reflect exactly a sarcopenic population but is likely to be those with the lowest muscle function within the study group based on the same characteristics. A second limitation is related to the fact that sensitivity to change could not have been measured in our study given its cross-sectional design. However, we aim to test the sensitivity to change in further analyses when prospective data about muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance are available for the EPOSA participants.

In conclusion, a valid SarQoL® English questionnaire is now available and can be used with confidence to understand better the burden of disease with sarcopenia and as a treatment outcome indicator in research. Before this study, the SarQoL® questionnaire had only been validated in one unique population study. With this study, we validated it in a second cohort from a different country. The psychometric properties indicated that the English version of the SarQoL® is valid, consistent and reliable which strengthens the evidence that the SarQoL® is a strong and valid tool for the assessment of quality of life in a sarcopenic population. Following the success of this study, we plan to go on to translate and validate the SarQoL® in other languages.

Key points.

A disease-specific tool is important to better detect effect of treatment and observe longitudinal changes of quality of life in subjects suffering from sarcopenia.

The English version of the SarQoL® has been developed and is valid, consistent and reliable.

An English version of the SarQoL® is available and can be used to better assess the disease burden associated with sarcopenia.

The SarQoL® questionnaire is available online www.sarqol.org

Funding

C.B. is supported by a Fellowship from the FNRS (Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique de Belgique—FRS-FNRS—www.frs-fnrs.be). C.B. and E.B. have received the “Young Investigator Research Grant” from the International Osteoporosis Foundation and Servier for the development and validation of the French version of the SarQoL questionnaire.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

C.C. has received consultancy fees and honoraria from Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Eli Lilly, GSK, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Takeda and UCB. Other authors: none declared.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

References

- 1.Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1851–60. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Cristini C, et al. Difficulties with physical function associated with obesity, sarcopenia, and sarcopenic-obesity in community-dwelling elderly women: the EPIDOS (EPIDemiologie de l’OSteoporose) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1895–900. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang S-F, Lin P-L. Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the association of sarcopenia with mortality. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016 doi: 10.1111/wvn.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:324–33. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Low relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:889–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rantanen T. Muscle strength, disability and mortality. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2003;13:3–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolland Y, Czerwinski S, Abellan Van Kan G, et al. Sarcopenia: its assessment, etiology, pathogenesis, consequences and future perspectives. J Nutr Heal Aging. 2008;12:433–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02982704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landi F, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Liperoti R, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality risk in frail older persons aged 80 years and older: results from ilSIRENTE study. Age Ageing. 2013;42:203–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaudart C, Reginster JY, Petermans J, et al. Quality of life and physical components linked to sarcopenia: the SarcoPhAge study. Exp Gerontol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper C, Dere W, Evans W, et al. Frailty and sarcopenia: definitions and outcome parameters. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1839–48. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper C, et al. Tools in the assessment of sarcopenia. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93:201–10. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9757-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaudart C, Rizzoli R, Bruyère O, Reginster J-Y, Biver E. Sarcopenia: burden and challenges for public health. Arch Public Health. 2014;72:45. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR. Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:395–407. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reginster J-Y, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, et al. Recommendations for the conduct of clinical trials for drugs to treat or prevent sarcopenia. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;28:47–58. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Arnal JF, et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93:101–20. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9758-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaudart C, Biver E, Reginster J-Y, et al. Development of a self-administrated quality of life questionnaire for sarcopenia in elderly subjects: the SarQoL. Age Ageing. 2015;44:960–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaudart C, Biver E, Reginster J-Y, et al. Validation of SarQoL®, a specific health-related quality of life questionnaire for sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syddall HE, Aihie Sayer A, Dennison EM, et al. Cohort profile: the Hertfordshire cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1234–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Pas S, Castell MV, Cooper C, et al. European project on osteoarthritis: design of a six-cohort study on the personal and societal burden of osteoarthritis in an older European population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunnally JC, B I. Psychometric theory. New York: McGrawHill Inc; 1994. at < http://www.amazon.com/Psychometric-Theory-Jum-C-Nunnally/dp/007047849X>. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Harwood RH, Cooper C, Aihie Sayer A. The SF-36: a simple, effective measure of mobility-disability for epidemiological studies. J Nutr Heal Aging. 2009;13:57–62. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33:337–43. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]