Abstract

Background: The updated Surviving Sepsis Campaign care bundles are associated with improved outcomes in patients with sepsis, yet adherence to the bundles remains inconsistent. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has adopted similar care bundles as a core measure that went into effect with October 1, 2015 discharges.

Objective: The aim of this study was to assess bundle compliance, length of stay (LOS), and in-hospital mortality before and after introduction of the new sepsis core measure.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted in 158 patients with a diagnosis of severe sepsis or septic shock from April 2015 to February 2016. The before group (n = 48) consisted of sequential patients discharged from April 1, 2015 to September 30, 2015 (prior to core measure implementation), and the after group (n = 110) consisted of sequential patients discharged from October 1, 2015 to February 29, 2016 (after core measure implementation).

Results: Significant improvement was seen in the after group compared to the before group for bundle compliance with the 3-hour (66.4% vs 31.3%; p < 0.01) and 6-hour (75.5% vs 41.7%; p < 0.01) components and the overall core measure (51.8% vs 16.7%; p < 0.01). In-hospital mortality was lower in the after group compared to the before group (14.5% vs 27.1%; p = 0.05), but this difference was not statistically significant. There was no significant difference in LOS.

Conclusions: The study found a significant increase in compliance with the sepsis care bundles since the implementation of this core measure. Increased adherence to the care bundles may improve in-hospital survival.

Keywords: care bundle, core measure, sepsis, septic shock

Sepsis is a syndrome characterized by life-threatening organ dysfunction in response to an infection. Patients who develop sepsis are at high risk for complications and death and have higher health care costs.1 The incidence of severe sepsis increases by approximately 13% each year in the United States, and it is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.2 In 2011 alone, sepsis accounted for more than $20 billion or 5.2% of total hospital costs in the United States.3 Early recognition and treatment of sepsis is associated with decreased mortality and improved patient outcomes. A summary of the evidence supporting the use of quantitative resuscitation has been reviewed previously.4

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) bundles were originally published in 2004 as best practice guidelines, and it was up to each individual institution to develop processes on how to incorporate these recommendations. Compliance with the SSC bundles is associated with improved outcomes in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. The International Multicentre Prevalence Study on Sepsis (the IMPreSS study) found a 40% reduction in hospital mortality with 3-hour bundle compliance and a 36% reduction with 6-hour bundle compliance.5 An analysis spanning 7.5 years found that compliance with the 2004 SSC bundles was associated with a 25% relative risk reduction in hospital mortality.6 The SSC bundles for severe sepsis and septic shock were most recently updated in 2015, and the National Quality Forum (NQF) adopted a similar care bundle to these revised SSC bundles.7,8 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has adopted the NQF sepsis care bundles as a chart-abstracted core measure known as the Early Management Bundle, Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock (SEP-1). This includes all patients with severe sepsis or septic shock discharged on or after October 1, 2015. The focus of the SEP-1 measure is on early diagnosis and rapid initiation of appropriate treatment. There are a minimum of 3 components and a maximum of 7 components for this measure; failure to comply with all required components will result in measure fallout as this is an “all or none” measure. These components are divided into 3- and 6-hour bundles.9 A core measure is a set of standards mandated by CMS that have demonstrated improved patient outcomes. Hospital reimbursement is determined by adherence to these core measures, so compliance is critical, especially for facilities with a high proportion of Medicare and Medicaid patients.10 A reimbursement strategy has not yet been established for the SEP-1 measure.

Many enhancements were developed at our institution in preparation for the SEP-1 measure, and these were implemented starting in October 1, 2015. In early 2015, a multidisciplinary sepsis committee was created and included physicians, pharmacy, nursing, quality, and information technology staff. The goal of this committee was to revise sepsis order sets and embed documentation tools into the electronic medical record (EMR) to make compliance with the SEP-1 measure easier. Specifically, order sets were created for adult sepsis resuscitation in the emergency department, sepsis admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), and sepsis admission to a non-ICU unit. Templates were created to assist providers in documenting severe sepsis and septic shock and for the fluid status and tissue perfusion assessment. An early warning system was implemented through the use of best practice advisory (BPA) messages in our EMR. These BPAs alert nurses and providers on the treatment team that a patient has screened positive for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria. The EMR provides a severe sepsis checklist for nursing to complete to ensure all necessary components of the SEP-1 measure are met if indicated. Providers are able to access the sepsis order sets from the BPA to allow for rapid initiation of treatment. A follow-up lactate alert is generated if the level comes back greater than 2 mmol/L and no order for a repeat lactate is present. A conditional order was designed to obtain a repeat lactate level automatically if a prior lactate level resulted as abnormal. Alerts are also generated for patients in septic shock without vasopressors ordered or if a volume status and tissue perfusion assessment has not been performed. Extensive education was provided to clinical staff on the recognition and treatment of sepsis, as well as on the components of the SEP-1 measure and the incorporation of all the new tools within the EMR.

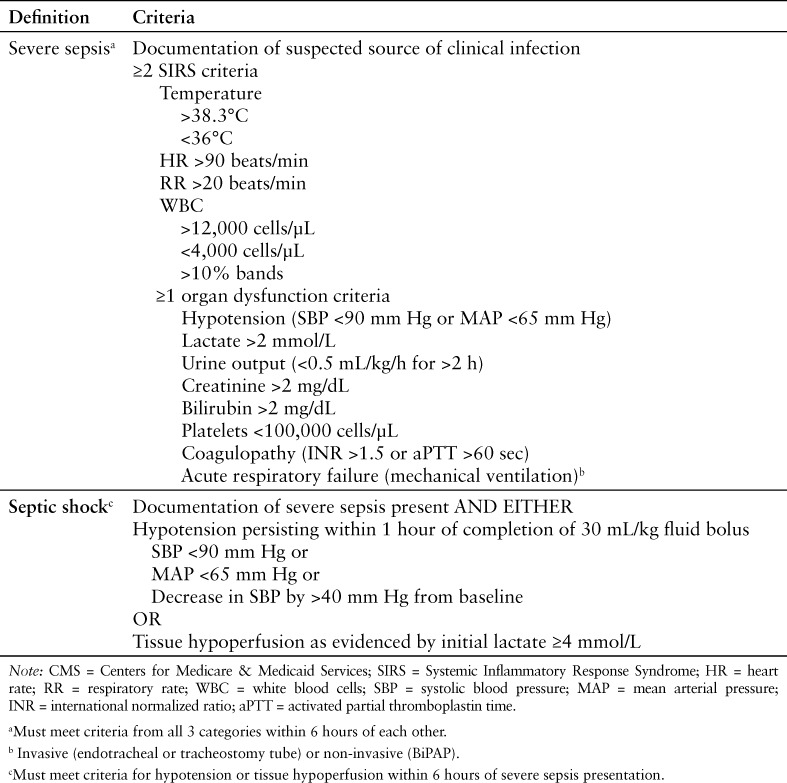

In the 2012 SSC guidelines, sepsis was diagnosed when a patient had confirmed or suspected infection and met at least 2 SIRS criteria. Severe sepsis was defined as having sepsis along with sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion or organ dysfunction. Sepsis-induced hypotension (as evidenced by hypotension due to infection, elevated lactate, or oliguria) that persists despite adequate fluid resuscitation constituted the definition for septic shock.11 The CMS definitions for severe sepsis and septic shock are similar to these 2012 SSC definitions. Specific criteria for SIRS and organ dysfunction as defined by CMS to determine the presence of severe sepsis or septic shock can be found in Table 1.12 For the purposes of this study, the terms sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock will be used in accordance with the CMS definitions. The objective of this quality improvement project was to assess bundle compliance and patient outcomes before and after the introduction of the new sepsis core measure at our 300-bed tertiary care hospital. The primary outcomes were meeting the 3-hour bundle, the 6-hour bundle, and the composite of the 3- and 6-hour bundles (SEP-1 measure compliance). Secondary outcomes included total length of stay (LOS), ICU LOS, and in-hospital mortality.

Table 1.

CMS criteria for severe sepsis and septic shock12

METHODS

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to compare adherence to the 3- and 6-hour sepsis care bundles and sepsis-related patient outcomes prior to and following the introduction of the SEP-1 core measure. All data were collected retrospectively for patients discharged between April 1, 2015 and February 29, 2016. The quality and compliance nurse at our institution provided a comprehensive list of patients during the defined study periods before and after implementation of the SEP-1 measure. Patients were identified using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) principal diagnosis codes of sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock. As this was a quality improvement project, our institutional review board deemed that no review was required.

All patients eligible for inclusion in the core measure were included in this study. The SEP-1 measure applies to patients at least 18 years of age admitted with a specified International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) principal or other diagnosis code for sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock (listed in Appendix A, Table 4.01 of the National Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Measures Specifications Manual).13 Patients are included in the measure if there is provider documentation of severe sepsis or septic shock or if the patient meets CMS-specified criteria for severe sepsis or septic shock (Table 1). Exclusion criteria for this study were based on CMS exclusion criteria for the measure and includes patients with directives for Comfort Care within 3 hours of presentation of severe sepsis or 6 hours of septic shock, LOS for more than 120 days, transferred from another acute care facility, expiration within 3 hours of presentation of severe sepsis or 6 hours of septic shock, or administration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics for more than 24 hours prior to the presentation of severe sepsis.9 Patients who did not meet the criteria for severe sepsis or septic shock through chart abstraction or who lacked provider documentation were classified as not having severe sepsis and were excluded from the study. The before group consisted of sequential historical patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) principal or other diagnosis code of sepsis (038), severe sepsis (995.92), or septic shock (785.52) discharged between April 1, 2015 and September 30, 2015 (prior to core measure implementation). The after group consisted of sequential patients discharged from October 1, 2015 through February 29, 2016 (after core measure implementation) with an ICD-10-CM diagnosis code of sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock.13

Utilizing the EMR, the following data for the 3-hour bundle were collected: time lactate obtained and initial level, time blood cultures obtained, time to administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, presence of septic shock, total crystalloid fluids received, and if a 30 mL/kg crystalloid fluid bolus was administered to patients with septic shock. Data collected for the 6-hour bundle included repeat lactate measurement if initial level was elevated (lactate ≥2 mmol/L), vasopressors initiated for persistent hypotension, and if a reassessment of volume status and tissue perfusion was performed for persistent hypotension or an initial lactate concentration of 4 mmol/L or greater. Persistent hypotension is defined by CMS as 2 consecutive readings of systolic blood pressure (SBP) less than 90 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure (MAP) less than 65 mm Hg, or a decrease in SBP of more than 40 mm Hg from baseline within 1 hour following the administration of a 30 mL/kg crystalloid fluid bolus.12 Specific broad-spectrum antibiotics (as defined in Appendix C, Tables 5.0 and 5.1 of the National Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Measures Specifications Manual), crystalloid fluids (0.9% sodium chloride or lactated Ringer's), and vasopressors (norepinephrine, dopamine, epinephrine, phenylephrine, or vasopressin) are required by CMS.12,14 For the volume status and tissue perfusion assessment, the patient must have either (a) focused bedside exam documented by a physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner or (b) any 2 of the following: central venous pressure measurement, central venous oxygen measurement, bedside cardiovascular ultrasound, passive leg raise, or fluid challenge. The focused bedside exam must include a full set of vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, respirations, and temperature), cardiopulmonary exam, capillary refill, peripheral pulse, and skin assessment.9

Baseline demographic data collected for all patients were age, gender, weight, admitting diagnosis, admitting level of care (medical/surgical, post-intensive care, or ICU), suspected infection source, SIRS criteria met, organ dysfunction criteria met, severe sepsis onset time, and septic shock onset time. Onset time for severe sepsis or septic shock is defined by CMS as the time the last criterion to classify a patient as having severe sepsis or septic shock is met or the time of provider documentation, whichever is earlier.12 Total hospital LOS, ICU LOS, and in-hospital mortality were collected for the secondary outcomes. LOS in the ICU was based on the number of days patients received ICU-level care. A Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was calculated for all patients using documented values within 6 hours of admission. The SOFA score is a validated tool to assess severity of organ dysfunction. A higher SOFA score correlates with an increased probability of mortality.15,16

Continuous data are described by mean and standard deviation, and the difference between the before and after groups was analyzed using nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test since Shapiro-Wilk tests for normality indicated that all numerical variables were not normally distributed. Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages and compared between the groups with either Pearson chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis was performed utilizing IBM SPSS Version 23 (IBM Corporation, Somers, New York).

RESULTS

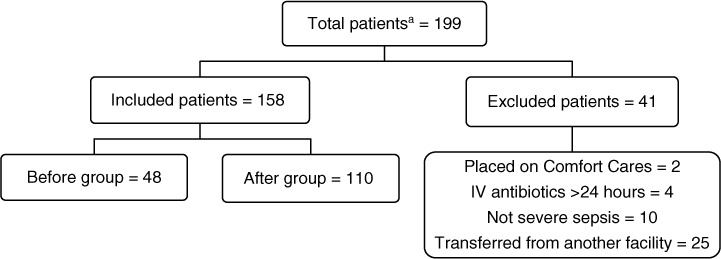

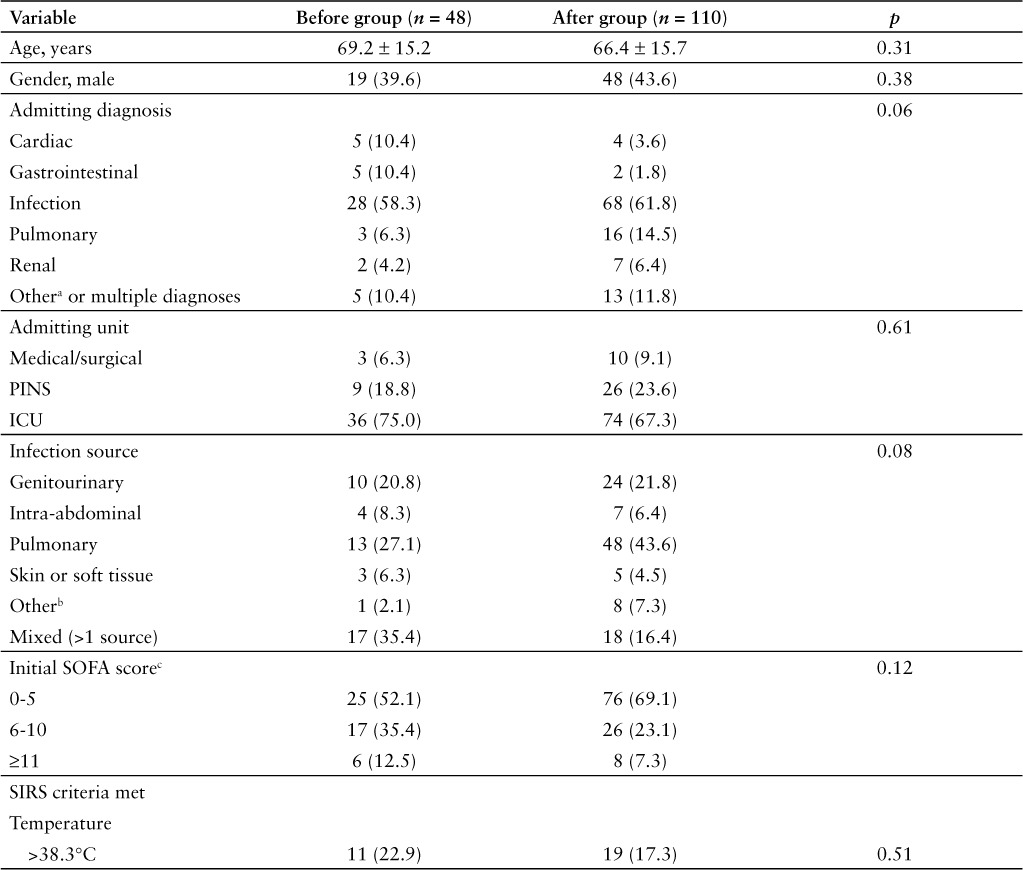

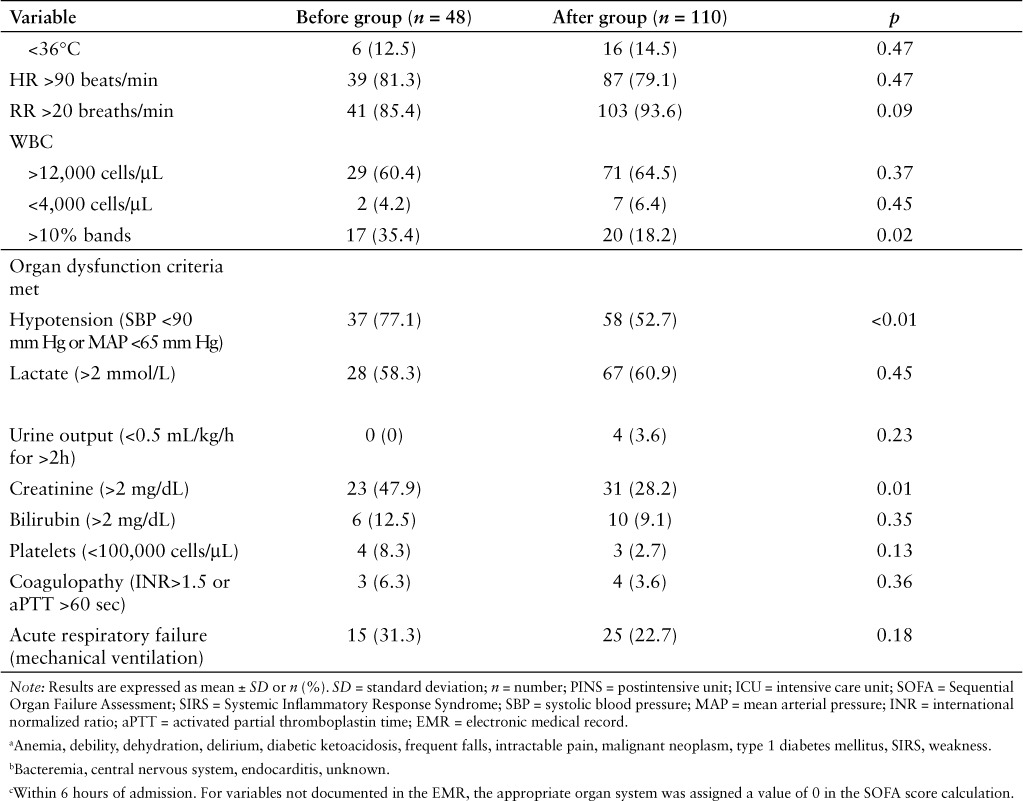

One hundred and ninety-nine patients were discharged from our facility with an ICD-9 or ICD-10-CM discharge diagnosis of sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock between April 1, 2015 and February 29, 2016. Of these, 158 patients were included in the study, with 110 patients in the after group (discharged after October 1, 2015) and 48 patients in the before group (discharged prior to October 1, 2015) (Figure 1). Baseline demographics were similar between groups (Table 2). Pulmonary and genitourinary infections were the most common sources of infection, and most patients had an initial SOFA score in the range of 0 to 5. The most frequent SIRS criteria met were tachycardia, tachypnea, and white blood cells (WBC) greater than 12,000 cells/μL. The only statistically significant difference found in baseline demographics was for patients having more than 10% banded WBC (18.2% in the study group vs 35.4% in the control group; p = 0.02). Hypotension, elevated lactate, elevated creatinine, and acute respiratory failure were the most frequent organ dysfunction criteria met. Statistically significant differences were seen between groups for organ dysfunction criteria of hypotension (52.7% in the study group vs 77.1% in the control group; p = 0.003) and elevated creatinine (28.2% in the study group vs 47.9% in the control group; p = 0.01).

Figure 1.

Patient distribution. aDischarged with a diagnosis of sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock based on ICD-9 (before group) or ICD-10-CM (after group) codes.

Table 2.

Patient demographics

Table 2.

Patient demographics (CONT.)

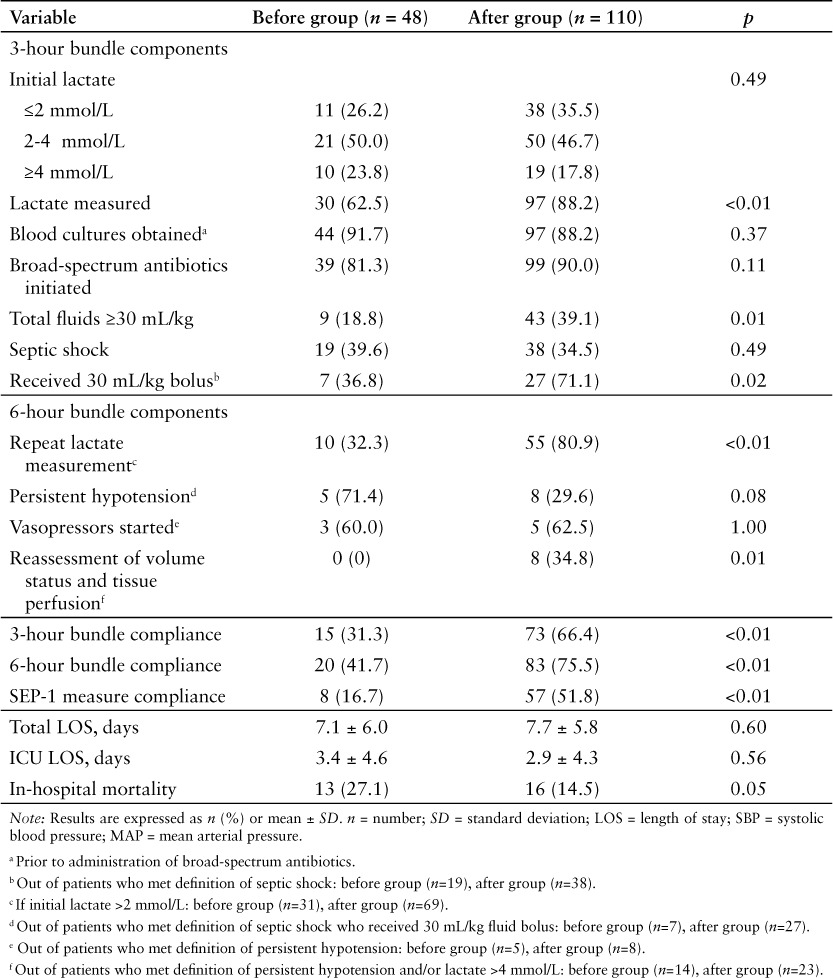

As expected, there was a statistically significant improvement observed in bundle and core measure compliance in the after group compared to the before group. For the 3-hour bundles, statistically significant increases were seen in the after group for obtaining lactate measurement (88.2% vs 62.5%; p < 0.01) and receiving a 30 mL/kg crystalloid fluid bolus both in general (39.1% vs 18.8%; p = 0.01) and for treatment of shock (71.1% vs 36.8%; p = 0.02) compared to the before group. A statistically significant increase was observed between groups in obtaining a repeat lactate measurement (80.9% in the after group vs 32.3% in the before group; p < 0.01) and for reassessing volume status and tissue perfusion (34.8% in the after group vs 0% in the before group; p = 0.01). No difference was observed in total LOS and ICU LOS between groups. In-hospital mortality was lower in the after group compared to the before group (14.5% vs 27.1%; p = 0.05), however this difference was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Compliance, length of stay, and mortality outcomes

DISCUSSION

The improvement in individual and overall bundle compliance seen in this retrospective observational study is likely due to enhancements made in our institution's processes, including updates to order sets, changes in documentation, and the implementation of an early warning system through BPA messages in our EMR. Our institution has also provided extensive education to clinical staff on the recognition and treatment of sepsis. The change that likely had the greatest impact on compliance with the SEP-1 measure was the implementation of BPA messages. This early warning system allows for the rapid identification of sepsis and provides immediate access to checklists and order sets to allow for the initiation of appropriate treatment. The tools also help to ensure SEP-1 compliance.

Although our institution saw improvement with bundle and SEP-1 measure adherence, with only 51.8% compliance there are still areas for improvement. In the IMPreSS study (which included 1,794 patients in 62 countries), overall compliance was 19% with the 3-hour bundle and 36% with the 6-hour bundle.5 We observed 66.4% compliance with the 3-hour bundle and 75.5% compliance with the 6-hour bundle. The most frequent causes of measure fallout in the study group were not receiving a 30 mL/kg fluid bolus, no reassessment of volume status and tissue perfusion, and not obtaining a repeat lactate level. Continuing to educate hospital staff on the importance of identifying sepsis early and meeting the SEP-1 components within the appropriate time frame will help increase awareness. The sepsis committee can continue to identify areas for improvement by carefully reviewing each patient chart that qualifies as a core measure “fallout” to identify deficiencies in processes and educate individual staff members involved in such fallouts. The tools in place should continue to evolve and be streamlined. Pharmacists can play a crucial role in measure compliance for individual patients by helping to ensure that appropriate timing, delivery, and documentation occurs for administration of antibiotics, crystalloid fluids, and vasopressors. They can also assist with order set optimization, responding to EMR alerts, and health care staff education.

This study exhibited several strengths. All patients who had the potential for inclusion in the SEP-1 core measure were included in this study, which helps to minimize the risk of selection bias as CMS only requires sampling of a specific number of patients based on the size of an institution's patient population.9 Meaningful data were found that can be presented to hospital staff and administrators, such as which criteria patients met the most frequently, the types of infection most commonly seen, and the finding that compliance with these measures may decrease hospital mortality. Since hospital reimbursement is based on adherence to CMS core measures, our results exhibiting improved compliance with the SEP-1 measure could demonstrate potential cost advantages for our hospital. However, since the reimbursement plan for SEP-1 measure compliance has not yet been outlined, this could not be specifically quantified as a study outcome. At our institution, we have a high proportion of Medicare and Medicaid patients, making compliance with CMS core measures even more crucial. The SEP-1 measure may begin to influence reimbursement as early as 2017, but no specific date has yet been provided by CMS.17

Our study also has some notable limitations. Since this was a single-center study with a relatively small sample size and short study period, generalizability is limited. Due to small sample size and infrequent event rate, multivariable logistic regression analysis of in-hospital mortality was unable to be performed to get reasonably stable estimates of the regression coefficients. Education and some process changes were implemented prior to the core measure going into effect, which could have created bias toward compliance in the control group. Because our study was not designed to account for all possible confounding factors, we are unable to directly establish reduced mortality with measure compliance. The decrease in hospital mortality bordered statistical significance (p = 0.051); with a larger sample size, it is possible that significance may have been observed. Another limitation is that the SEP-1 measure and definitions and treatment of sepsis continue to evolve, which can make comparisons difficult.

Updated definitions and clinical criteria for sepsis and septic shock were published in February 2016, with the category of severe sepsis being removed. Sepsis is now defined as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection” and septic shock as “a subset of sepsis in which underlying circulatory and cellular/metabolic abnormalities are profound enough to substantially increase mortality.” An increase in baseline SOFA score of 2 points or more is representative of organ dysfunction. The SIRS criteria are no longer used to identify sepsis and have instead been replaced with the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score (respiratory rate 22 breaths/min or higher, altered mental status, or SBP 100 mm Hg or less). Having an infection with at least 2 of the qSOFA criteria can be used to rapidly identify patients at increased risk of poor outcomes.1 It is unknown at this time if or when these updated definitions will be incorporated into the SEP-1 measure, which has created challenges for clinicians.

The next version of the SEP-1 measure began with July 1, 2016 discharges with some notable changes.18 The first change is the requirement of a 30 mL/kg fluid bolus (must be given in entirety) for all patients with severe sepsis presenting with initial hypotension (one SBP reading of less than 90 mm Hg or MAP less than 65 mm Hg within 6 hours prior to or after the presentation of severe sepsis), in addition to being required for patients with septic shock or an initial lactate concentration of 4 mmol/L or higher. The second change pertains to antibiotic selection. Previously, in order to satisfy the antibiotic requirement, CMS-defined appropriate antibiotic therapy was necessary.14 With the update, if there is laboratory or provider documentation of the causative organism with susceptibilities, any IV antibiotic identified as being appropriate to treat said causative organism will satisfy the requirement. The third change is the addition of the balanced crystalloid solutions Normosol and PlasmaLyte as acceptable crystalloid fluids. The last change is that any patient discharged within 3 hours of severe sepsis presentation is now excluded from the SEP-1 measure.19 These changes demonstrate the evolving nature of the SEP-1 measure and the need for frequent adjustments to treatment pathways.

CONCLUSION

Our institution has shown a significant increase in compliance with sepsis care bundles since the implementation of the SEP-1 measure by CMS. This increased compliance may help improve patient in-hospital survival at our institution. Future larger studies are necessary to determine whether a mortality benefit associated with core measure compliance (3-hour, 6-hour, and overall compliance) truly exists.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Special thanks to Keriann Collmann, BSN, RN, Quality & Compliance Nurse, CHI Health Immanuel, Omaha, Nebraska, and Yongyue Qi, Research Analyst (Biostatistics Support), Creighton University School of Pharmacy & Health Professions, Omaha, Nebraska.

REFERENCES

- 1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, . et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016; 315( 8): 801– 810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG.. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41( 5): 1167– 1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Torio CM, Andrews RM.. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer, 2011. Statistical Brief #160. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. August 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK169005. Accessed May 15, 2016. [PubMed]

- 4. Welch SC, Bauer SR.. Initial care for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: The next ICU quality measure. Hosp Pharm. 2016; 51( 1): 19– 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rhodes A, Phillips G, Beale R, . et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundles and outcome: Results from the International Multicentre Prevalence Study on Sepsis (the IMPreSS study). Intens Care Med. 2015; 41( 9): 1620– 1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, . et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Crit Care Med. 2015; 43( 1): 3– 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Quality Forum. . Severe sepsis and septic shock: Management bundle. 2013. http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/0500. Accessed May 30, 2016.

- 8. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee. . Updated bundles in response to new evidence. 2015. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/SSC_Bundle.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2016.

- 9. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission. . Severe sepsis and septic shock (SEP). Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures: Discharges 10-01-15 (4Q15) through 06-30-16 (2Q16). Version 5.0b. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2015: SEP-1-1-SEP-1-50. https://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed May 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. . Core measures. 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core-Measures.html. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 11. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, . et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41( 2): 580– 637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission. . Alphabetical data dictionary. Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures: Discharges 10-01-15 (4Q15) through 06-30-16 (2Q16). Version 5.0b. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2015: 1-330-1-343. https://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed May 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission. . Appendix A.1: ICD-10 code tables. Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures: discharges 10-01-15 (4Q15) through 06-30-16 (2Q16). Version 5.0b. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2015: A-3 https://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed May 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission. . Appendix C: medication tables. Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures: Discharges 10-01-15 (4Q15) through 06-30-16 (2Q16). Version 5.0b. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2015: C-2-4. https://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed May 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, . et al; Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intens Care Med. 1996; 22( 7): 707– 710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, . et al; Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: Results of a multicenter, prospective study. Crit Care Med. 1998; 26( 11): 1793– 1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. . Fact sheet: CMS to improve quality of care during hospital inpatient stays. 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheetsitems/2014-08-04-2.html. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- 18. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission. . National hospital inpatient quality reporting measures specifications manual: release notes. Version 5.1. 2015. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/IQR_Release_Notes_version_5.1.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- 19. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission. . Severe sepsis and septic shock (SEP). Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures: discharges 07-01-16 (4Q15) through 12-31-16 (2Q16). Version 5.0b. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2016: SEP-1-SEP-1-51. https://www.joint-commission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed June 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]