Abstract

Religiosity, often measured as attendance at religious services, is linked to better physical health and longevity though the mechanisms linking the two are debated. Potential explanations include: a healthier lifestyle, increased social support from congregational members, and/or more positive emotions. Thus far, these mechanisms have not been tested simultaneously in a single model though they likely operate synergistically. We test this model predicting all-cause mortality in Seventh-day Adventists, a denomination that explicitly promotes a healthy lifestyle. This allows the more explicit health behaviors linked to the religious doctrine (e.g., healthy diet) to be compared with other mechanisms not specific to religious doctrine (e.g., social support and positive emotions). Finally, this study examines both Church Activity (including worship attendance and church responsibilities) and Religious Engagement (coping, importance, and intrinsic beliefs). Religious Engagement is more is more inner-process focused (vs. activity-based) and less likely to be confounded with age and its associated functional status limitations, although it should be noted that age is controlled in the present study. The findings suggest that Religious Engagement and Church Activity operate through the mediators of health behavior, emotion, and social support to decrease mortality risk. All links between Religious Engagement and mortality are positive but indirect through positive Religious Support, Emotionality, and lifestyle mediators. However, Church Activity has a direct positive effect on mortality as well as indirect effects through, Religious Support, Emotionality, and lifestyle mediators (diet and exercise). The models were invariant by gender and for both Blacks and Whites.

Keywords: worship, religious engagement, lifestyle, emotionality, social support, physical health, mortality

The evidence linking religion to better physical health is substantial and includes decreased morbidity such as cardiovascular, pulmonary and metabolic diseases (Larson, Swyers, & McCullough, 1997); better recovery and increased quality of life following illness (Harris, Dew, & Lee, 1995; Landis, 1996); and decreased mortality risk (Chida, Steptoe, & Powell, 2009; McCullough, Friedman, Enders, & Martin, 2009; McCullough, Hoyt, Larson, Koenig, & Thoresen, 2000; Schnall et al., 2010). The mechanisms linking religion to health, however, are not yet well understood and several continue to be investigated. Religion as a promoter of healthy lifestyle, a means of social support, and as an aid to emotion regulation are perhaps three of the most promising possibilities and will be investigated here (Ellison & George, 1994; Ellison & Levin, 1998; George, Ellison, & Larson, 2002).

Religion and Healthy Lifestyle

Religious organizations typically encourage adherence to denominational directives, and religiously-linked social norms often exist in addition to the more explicit mandates. Both of these (norms and explicit mandates) may encourage health-relevant choices and the empirical evidence supports this link. Specifically, measures of religiosity have been linked to lower smoking rates and decreased likelihood of ever beginning to smoke, and the associations between religiosity and decreased use/abuse of alcohol and other drugs are also well-documented (Blazer, Hays, & Musick, 2002; Brown, Parks, Zimmerman, & Phillips, 2001; Califano Jr et al., 2001; Edlund et al., 2010; Gillum, 2005; Hope & Cook, 2001; Koenig, George, et al., 1998; Michalak, Trocki, & Bond, 2007). Regular church attendance has also been associated with greater physical activity (T. D. Hill, Burdette, Ellison, & Musick, 2006; Strawbridge, Shema, Cohen, & Kaplan, 2005) and better diet (T. D. Hill et al., 2006; Holt, Haire-Joshu, Lukwago, Lewellyn, & Kreuter, 2005). The variety of links between religion and specific health behaviors suggests that a healthy lifestyle (Cockerham, 2005) may be fostered by religious engagement. Religious engagement likely encourages healthy lifestyle patterns in certain domains such as substance use/abuse that spread to other healthy choices like diet and exercise ultimately promoting health and preventing disease (Boswell, Kahana, & Dilworth-Anderson, 2006). Those who are religious, engage in more health-promoting behaviors and fewer health risk behaviors than those who are less so and this holds across gender and racial/ethnic groups (T. D. Hill, Ellison, Burdette, & Musick, 2007). These behaviors are likely influenced by denominational pro- and prescriptions, however, they may also be influenced by improved mental health and social relationships that may also result from religious engagement (Strawbridge et al., 2005). Thus, the health behavior “spread” suggested by Boswell et al. (2006) may most often move from behaviors that are directly addressed by doctrinal directives to those that are not formally included but nevertheless have become normative, or that are simply fostered by the improved social networks and/or emotional states that accrue to the original behaviors.

Religion and Social Support

Social support is another mechanism through which religion may link to physical health outcomes. Religious organizations facilitate social integration—congregants often view one another as if they were family members and provide advice or tangible, but informal, support such as help with transportation or meals. Religious groups also often have formal assistance programs to help those who are struggling with finances, activities of daily living, or significant life transitions. Finally, religious congregations bring together, on a regular basis, people who share common values, commitments, and goals. This contributes to a sense of connectedness and a feeling of support (Ellison & George, 1994).

Links between social support and health are well-recognized (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Seeman, 1996; Uchino, 2004) and are rooted in Durkheim’s work on the importance of social integration (Berkman et al., 2000). Although social support can come from various sources, religious communities represent an important source of social support for their members, with religious engagement and church activity being associated both with informal support and satisfaction with support (Bradley, 1995; Ellison & George, 1994; Hatch, 1991; Taylor & Chatters, 1988). Additionally, some (e.g., Strawbridge, Cohen, Shema, & Kaplan, 1997; Van Olphen et al., 2003) but not all studies (e.g., Edlund et al., 2010; Maselko, Kubzansky, Kawachi, Seeman, & Berkman, 2007) find that social support plays a mediating role between religiousness and health outcomes. Because worship attendance decreases with advanced age and decreased health, social support may not be the primary mediator in all older adults (Hayward & Krause, 2013; Wang, Kercher, Huang, & Kosloski, 2014). It is important to examine elements of religiosity other than worship attendance that may remain strong with advancing age and health problems to more clearly determine whether social support mediates the religion-health relationship in older adults.

Religion and Emotions

Emotional states have been linked to health outcomes through a variety of pathways (Salovey, Rothman, Detweiler, & Steward, 2000) including cardiovascular reactivity (Friedman, 1992; van Melle et al., 2004), immune functioning (Denson, Spanovic, & Miller, 2009; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004), and health behaviors (e.g., Brandon, 1994; Brandon, Tiffany, Obremski, & Baker, 1990; Glassman et al., 1990). Religion provides a framework for understanding the world in ways that may garner positive emotions that are beneficial to health. Especially for uncontrollable, negative events, religion can enable one to find meaning and can facilitate positive emotions and coping strategies (Frazier, Tashiro, Berman, Steger, & Long, 2004; Kunst, Bjorck, & Tan, 2000; Park, 2005). Stressful events may feel less threatening when one views them as opportunities to learn or grow closer to the Sacred and crises more manageable if one believes that they are meaningful instead of pointless and random (Pargament, 2011). Therefore, one might expect fewer negative emotions among those who filter experiences through a religious overlay. For example, those with a religious orientation may respond to stressful events with positive religious coping that garners strength, comfort, and a sense of control from a relationship with the Sacred; these more positive emotions are beneficial to health (Koenig, Pargament, & Nielsen, 1998; Pargament, Koenig, Tarakeshwar, & Hahn, 2004; Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998).

There are data to support each of these possibilities. One illustration is the work of Williams, Larson, Buckler, Heckmann, and Pyle (1991). Williams and colleagues (1991) demonstrated that although worship frequency was not directly related to distress, it did serve as a buffer, improving the well-being for those encountering stressful life events. More recent examples have found that positive, but not negative, religious coping is useful in adjusting to stressful situations (Terreri & Glenwick, 2011) and that negative religious coping is, in fact, as detrimental to well-being as positive religious coping is helpful (Pargament, Tarakeshwar, Ellison, & Wulff, 2001), a distinction that is especially dramatic in the very religious (i.e., clergy; Pargament et al., 2001).

We think religious engagement that includes positive religious coping, intrinsic religiousness, and a religious orientation will impact health by decreasing negative emotionality. We know, for example, that Seventh-day Adventists who use positive religious coping after divorce have fewer depressive symptoms (Webb et al., 2010). In addition, worship is associated with fewer depressive symptoms and more positive affect (Patrick & Kinney, 2003). What is uncertain is whether the link between religious engagement and health outcomes is mediated by emotions when simultaneously assessing worship frequency and intrinsic religious engagement (Parker et al., 2003). In an earlier paper, Morton, Lee, Haviland, and Fraser (2012) found that religious engagement predicted perceived health indirectly through negative emotionality. Based on this work, we propose that emotions indicating poorer mental health (negative affect, anxiety, depression) may mediate the religion to mortality relationship. Religious engagement and worship activities often result in comforting and positive emotions through messages of compassion, forgiveness, and love that can decrease the negative emotions that may lead to psychopathological symptoms and disorders.

Present Study

The goal of the present study is to examine, in a single structural equation model, three major pathways between religion and mortality: social support, negative emotionality, and lifestyle. Research supports each mediator independently, but, they have not been examined together in a denomination that has extremely low use of alcohol and tobacco. In the past, several key researchers (Maselko et al., 2007; Seeman, Dubin, & Seeman, 2003) have concluded that religion is likely linked to health via social support. However, these studies assessed religion using only church attendance that may be confounded with declines in health in late life. This study will examine three functional religion-health mediators (social support, negative emotionality, lifestyle) with both Church Activity and intrinsic Religious Engagement included in the model. This approach will serve several purposes–to test all mediators at once as they may work synergistically (social support from congregants may decrease negative emotions; less negative emotionality may foster better health habits; and so on); to determine whether similar mediators operate when religion is assessed as a behavior (church responsibilities and attendance at services) compared to a more internal religious belief construct (coping, importance, intrinsic religiousness) that may remain constant in the face of ill health and functional status limitations that can accompany advancing age.

We hypothesize that both Church Activity and Religious Engagement will predict Mortality directly and that all three mediators will be important. That is, Religious Engagement is expected to demonstrate not only a direct association with Mortality but also to operate indirectly through Church Activity, Positive Social Support, less Negative Emotionality, and Healthy Diet and Exercise. Because the sample is comprised of Seventh-day Adventists, for whom religious practice specifically involves a healthy diet, we expect that healthy lifestyle (Healthy Diet and Exercise) will be especially useful explanatory variables. Church Activity, too, is hypothesized to predict Mortality both directly and indirectly through Positive Social Support, lower levels of Negative Emotionality, and Healthy Diet and Exercise.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

These data were gathered as part of the Biopsychosocial Religion and Health Study (BRHS), a cohort study of Seventh-day Adventists designed to address religious engagement and health, with initial data collection in 2006–07 (Lee et al., 2009). Approximately 21,000 BRHS participants were randomly sampled from participants in the Adventist Health Study–2 (AHS-2), a cohort study of 96,194 Adventists designed to answer questions about lifestyle, mortality, and cancer risk with initial data collection in 2003–04. Blacks (i.e., African Americans, West Indian/Caribbean descendants, Bi-racial) were oversampled (Butler et al., 2008). The BRHS White response rate was 60%, and the Black response rate 31% for a total sample of 10,988 to a 20-page questionnaire with 2 postcard reminders. There were 253 non-SDAs and 365 inactive SDAs in the sample who were excluded. Regarding age, 134 individuals under age 35 were excluded. Next, 700 who were neither Black nor White were excluded. Finally, 3005 individuals who were missing data on any of the study variables were also excluded leaving 6,531 participants for the present analyses.

Table 1 shows the sample demographics. There were more females than males, and more Whites than Blacks. Most had at least some college education, and the majority (51.67%) was between the ages of 45 and 64 (with an age range 35–104). The median age was 59 and the mean 59.9. More than half had no difficulty meeting their expenses for basic needs in the last year, and 91.9% attended church at least weekly. Additionally, data on the tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking rates in our sample were collected in the Adventist Health Study-2, 1 to 4 years before our questionnaire. The rates were 0.6% (36) smoked, 5.5% (360) drank, 0.3% (18) did both and 93.7% (6117) neither drank nor smoked.

Table 1.

Demographics (N=6,351)

| % | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 64.9% | 4236 |

| Male | 35.1% | 2295 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 66.0% | 4313 |

| Black | 34.0% | 2218 |

| Age | ||

| 35 – 44 | 12.6% | 826 |

| 45 – 54 | 24.2% | 1580 |

| 55 – 64 | 27.4% | 1789 |

| 65 – 74 | 20.4% | 1331 |

| 75 – 84 | 12.4% | 809 |

| 85 – 94 | 2.9% | 188 |

| 95 – 104 | .1% | 8 |

| Difficulty Meeting Basic Needs Last Yr. | ||

| Not at all | 71.0% | 4638 |

| A little | 15.4% | 1003 |

| Somewhat | 5.8% | 381 |

| Fairly | 4.5% | 291 |

| Very | 3.3% | 218 |

| Education | ||

| Grade School | 1.1% | 74 |

| Some High School | 3.2% | 208 |

| High School diploma | 11.2% | 732 |

| Trade school diploma | 4.8% | 316 |

| Some college | 21.3% | 1389 |

| Associate degree | 11.8% | 772 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 24.7% | 1611 |

| Master’s degree | 15.2% | 991 |

| Doctoral degree | 6.7% | 438 |

| Attend church of religious meetings | ||

| More than once a week | 42.0% | 2744 |

| Once a week | 48.9% | 3195 |

| A few times a month | 5.9% | 385 |

| A few times a year | 2.4% | 155 |

| Once a year or less | 0.6% | 37 |

| Never | 0.2% | 15 |

| Mortality | ||

| Alive | 96.5% | 6305 |

| Dead | 3.5% | 226 |

Measures

Control variables

Age; difficulty meeting expenses for basic needs (Pudrovska, Schieman, Pearlin, & Nguyen, 2005) like food, clothing, and housing in the last year (1 not at all to 5 very); and education (1 grade school to 9 doctorate) were controlled in all analyses. Distributions of the control variables can also be found in Table 1.

Latent constructs

For our structural equations models (SEM), we initially formed six constructs: Religious Engagement, Church Activity, Positive Social Support, Negative Emotionality, Healthy Diet, and Exercise. Each was formed from two to four manifest variables described below. Cronbach’s α statistics given below are from our full sample of 10,988. Means and standard deviations of the manifest variables making up the seven constructs are found in Table 2 along with gender and ethnic differences.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Manifest Variables

| Latent Variable | Total Sample (n=6531)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manifest Variable | Mean | SD | Max | Min |

| Religious Engagement | ||||

| How religious are you? | 8.81 | 1.49 | 10 | 0 |

| Intrinsic Religiosity | 6.34 | 0.94 | 7 | 1 |

| Positive Religious Coping | 4.12 | 0.7 | 5 | 1 |

| Church Activity | ||||

| Worship Attendance | 1.71 | 0.76 | 6 | 1 |

| Responsibilities on Sabbath hours/time | 3.56 | 1.73 | 7 | 1 |

| Responsibilities on Sabbath times/month | 2.12 | 1.56 | 4 | 0 |

| Positive Social Support | ||||

| Religious Emotional Support Given | 3.34 | 0.86 | 5 | 1 |

| Religious Emotional Support Received | 3.11 | 0.89 | 5 | 1 |

| Anticipated Church Support | 3.23 | 0.76 | 4 | 1 |

| Congregational Sense of Community | 5.08 | 1.02 | 7 | 1 |

| Negative Emotionality | ||||

| CES-Depression | 8.97 | 8.63 | 52.09 | 0.53 |

| Neuroticism | 2.87 | 1.11 | 7 | 1 |

| Negative Affect | 1.73 | 0.71 | 5 | 1 |

| Healthy Diet | ||||

| Fruits | 5.99 | 1.48 | 8 | 1 |

| Cruciferous vegetables | 3.97 | 1.5 | 8 | 1 |

| Other leafy green vegetables | 4.57 | 1.37 | 8 | 1 |

| Nuts | 4.51 | 1.68 | 8 | 1 |

| Beans | 3.91 | 1.32 | 8 | 1 |

| Exercise | ||||

| Vigorous activities times/week | 3.99 | 2.29 | 8 | 1 |

| Vigorous activities minutes/session | 4.11 | 2.11 | 8 | 1 |

| Regular exercise program | 1.44 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

Note: Means in the same row not sharing the same subscript are significantly different at p< .05 in the two-sided test of equality for column means. Tests assume equal variances. Tests are adjusted for all pairwise comparisons within a row using the Bonferroni correction.

Religious Engagement

Assessed with three scales: (a) functional religious activity with five positive religious coping items (α=.74) from the Brief RCOPE (Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, 2000), (b) a global self-assessment - “How religious are you?” rated on a zero not religious at all to 10 strongly religious scale; and, (c) an assessment of religious motivation with three intrinsic religiosity items (α=.71) from the Duke University Religion Index (Koenig, Parkerson, & Meador, 1997). These religious experience measures have been associated with better physical health (Hall, Meador, & Koenig, 2008).

Church Activity

Assessed with three items: (a) church attendance, (b) number of Sabbaths per month with church responsibilities; and (c) the number of hours spent in such responsibilities when they occur. Church attendance was measured on a scale from Never (0) to More than once a week (6). The Sabbath responsibilities times per month question was: “On how many Sabbaths in an average month do you have responsibilities in your church? (For example, giving scripture and prayer, teaching Sabbath School, providing music, preparing for a potluck, etc.)” with possible responses of No Sabbaths (1) to 4 or more Sabbaths (5). The Sabbath responsibilities question was “On a Sabbath when you have responsibilities, how many hours do they usually take up? (Include preparation time on Sabbath such as preparing a lesson study, practicing music, preparing a meal for potluck, etc.).” Possible responses were I have no church responsibilities, less than hour, to 1 hour, 1 to 2 hours, 3 to 4 hours, 5 to 6 hours, and More than 6 hours.

Positive Religious Support

Religious support from “people you worship with-people in your local church, Bible study class, or Sabbath school class” was assessed with two, 3-item subscales from Krause’s (1999) Religious Support Scale: (a) emotional support given (α =.82); and (b) emotional support anticipated (α =.91). The emotional support given scale was rated on a 1 never to 5 very often rating scale (e.g., “How often do you make the people you worship with feel loved and cared for?”). The anticipated support scale was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from none to a great deal (e.g., “If you were ill, how much would the people in your congregation be willing to help out?”). The Congregational Sense of Community scale (based on Pargament’s items) (P. C. Hill & Hood, 1999) was a 10-item scale rated on a 7-point scale ranging from not true to very true (e.g., “Members treat each other as family (for example, visiting the sick, celebrating anniversaries, etc.; Most members are close friends with each other.).

Negative Emotionality

This construct assessed emotional symptoms in the last month with three scales. Depression was assessed with the 11-item short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (α=.80) (Kohout, Berkman, Evans, & Cornoni-Huntley, 1993). Each item had four response options: Rarely or none of the time (Less than 1 day), Some or a Little of the Time (1–2 days), Occasionally or a Moderate Amount of the Time (3–4 days), Most or All of the Time (5–7 days). These items were converted to the 20-item scale scores with the Kohout et al. (1993) algorithm. Negative affect was assessed with the five-item negative affect subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (α=.87) (Mackinnon et al., 1999). Respondents were asked to rate five emotions (afraid, upset, nervous, scared, and distressed) on how often they had felt that way during the past year on a 4-point scale (Very Slightly or Not At All to Extremely). Neuroticism was assessed with the eight-item Big Five Inventory Neuroticism Scale (α=.81) (John, Srivastava, Pervin, & John, 1999) with a seven-point rating scale (Not true to Very true).

Healthy Diet

Assessed frequency of healthy food consumption in the past 12 months (8 options from never or rarely to 4+ times per day): fruits, cruciferous greens, green leafy vegetables, nuts, and beans. “Fruits” were described as “any kind” including frozen, canned, dried, raw, or cooked; “cruciferous greens” included broccoli, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, kale, collards, mustard greens, poke salad, and rucola; “green leafy vegetables” included lettuces, cooked or raw spinach, and similar leafy greens; “nuts” included all types; and “beans” included red, pinto, and broad beans as well as lentils, chick peas, gungo p eas, bean or lentil soups, and refried beans.

Exercise

Assessed with responses to three items: (a) “How many times per week do you usually engage in regular vigorous activities, such as brisk walking, jogging, bicycling, etc., long enough or with enough intensity to work up a sweat, get your heart thumping, or get out of breath?” (8 options from never to 6 or more times were week), (b) “On average, how many minutes do you exercise each session?” (8 options from None to more than 1 hour), (b) “Do you have a regular exercise program? (Yes or No), (c) “On average, how many minutes do you exercise each session? Choose the best answer. (8 options from None to more than 1 hour). These items have been previously validated in Black and White Seventh-day Adventists (Singh, Fraser, Knutsen, Lindsted, & Bennett, 2001; Singh, Tonstad, Abbey, & Fraser, 1996).

Mortality

Participants were followed from questionnaire completion to death and mortality data were obtained by matching personal identifiers with data from The National Death Index through December 31, 2011. Deaths from all causes were included.

Results

Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS 22 and Structural Equation Modeling with Amos 22. For scales, missing data was handled as a mean of available items; means were calculated if only one missing item occurred on the 3–5 item scales, two on the 6–10 item scales and 3 on the >10 item scales. A total of 6,531 (59.4%) met inclusion criteria. Compared to the 4,473 excluded participants, the 6,531 included were younger (M = 59.9, SD = 12.9 vs. M = 63.8, SD = 14.4), more educated (46.5% vs. 38.8% ≥ college graduate), less likely to be female (64.9% vs. 72.0%), more likely to be White (66.0% vs. 49.8%) and less likely to have died (3.5% vs 5.9%). All ps for these comparisons < .0005. We first set up a general model of our latent variables. This was hierarchical: Religious Engagement was set as the independent variable for all other latent variables. Church Activity was set as the independent variable for all other variables except Religious Engagement. Positive social support was set as the independent variable for all other variables except Religious Engagement and Church Activity and so on. We used modification indices to determine potential connections among errors in measurement of manifest variables and where it made logical sense to add such connections, we did so. For example, modification indices suggested that the measurement errors for cruciferous greens and green leafy vegetables were correlated. Since both were assessing similar diet elements we included a connection between the error terms for these two variables. All path coefficients and their confidence limits were determined by a 10,000 sample bias-corrected bootstrap. We had a very large sample which tended to make even weak path connections statistically significant so in our final model we dropped all connections that were not statistically significant beyond the p=.001 level.

Complete Model of Religious Engagement and Mortality

Table 2 shows the means, and standard deviations for all manifest variables included inthe model.

Control variables

Table 3 shows that most control variables were related to the latent structural variables. Age was most consistently related to the latent variables, linking to more Religious Engagement, Positive Religious Support, Healthy Diet, and Mortality. On the other hand, age was related to less Church Activity, Negative Emotionality, and Exercise. Being Black was related to more Religious Engagement and Church Activity, and to less Healthy Diet; and, weakly, to lower Mortality. Difficulty meeting expenses was negatively related to Religious Engagement and Exercise and positively related to Negative Emotionality. Education was positively related to more Religious Engagement, Healthy Diet and Exercise, as well as negatively related to Positive Religious Support and Negative Emotionality. Being male was related to less Religious Engagement, Negative Emotionality, and Healthy Diet but to more Church Activity, Exercise, and, weakly, to higher Mortality.

Table 3.

Standardized Control Variable Regression Weights for the All Paths Model

| Variable

|

95% CI

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | → Dependent | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p |

| Age | → Church Activity | −0.13 | −0.16 | −0.10 | .000 *** |

| Age | → Exercise | −0.15 | −0.18 | −0.12 | .000 *** |

| Age | → Healthy Diet | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.14 | .000 *** |

| Age | → Mortality | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.22 | .000 *** |

| Age | → Negative Emotionality | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.05 | .000 *** |

| Age | → Positive Religious Support | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | .036 * |

| Age | → Religious Engagement | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.26 | .000 *** |

| Black | → Church Activity | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 | .000 *** |

| Black | → Exercise | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | .439 |

| Black | → Healthy Diet | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.16 | .000 *** |

| Black | → Mortality | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.00 | .039 * |

| Black | → Negative Emotionality | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | .120 |

| Black | → Positive Religious Support | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 | .012 * |

| Black | → Religious Engagement | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.21 | .000 *** |

| Difficulty Meeting Needs | → Church Activity | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | .208 |

| Difficulty Meeting Needs | → Exercise | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.02 | .000 *** |

| Difficulty Meeting Needs | → Healthy Diet | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.00 | .077 |

| Difficulty Meeting Needs | → Mortality | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 | .149 |

| Difficulty Meeting Needs | → Negative Emotionality | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.27 | .000 *** |

| Difficulty Meeting Needs | → Positive Religious Support | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.02 | .800 |

| Difficulty Meeting Needs | → Religious Engagement | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.03 | .000 *** |

| Education | → Church Activity | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | .089 |

| Education | → Exercise | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.11 | .000 *** |

| Education | → Healthy Diet | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.26 | .000 *** |

| Education | → Mortality | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | .559 |

| Education | → Negative Emotionality | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.06 | .000 *** |

| Education | → Positive Religious Support | −0.10 | −0.12 | −0.07 | .000 *** |

| Education | → Religious Engagement | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.06 | .016 * |

| Male | → Church Activity | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 | .000 *** |

| Male | → Exercise | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 | .000 *** |

| Male | → Healthy Diet | −0.10 | −0.13 | −0.07 | .000 *** |

| Male | → Mortality | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | .039 * |

| Male | → Negative Emotionality | −0.19 | −0.21 | −0.16 | .000 *** |

| Male | → Positive Religious Support | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 | .353 |

| Male | → Religious Engagement | −0.12 | −0.15 | −0.09 | .000 *** |

Measurement variables

Table 4 shows the regression weights for our measurement model. All measurement variables were strongly related to their latent variable.

Table 4.

Standardized Measurement Model Regression Weights Full Model for the All Paths Model

| Variable

|

95% CI

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | → Dependent | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p |

| Religious Engagement | → Intrinsic Religiosity | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.79 | .000 *** |

| Religious Engagement | → Positive Religious Coping | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.75 | .000 *** |

| Religious Engagement | → Your Religiousness | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.63 | .000 *** |

| Church Activity | → Sabbath Responsibilities (hours) | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.81 | .000 *** |

| Church Activity | → Sabbath Responsibilities (times) | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.83 | .000 *** |

| Church Activity | → Worship Attendance | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.53 | .000 *** |

| Positive Religious Support | → Relig. Support Anticipated | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.59 | .000 *** |

| Positive Religious Support | → Relig. Support Given | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.86 | .000 *** |

| Positive Religious Support | → Sense of Community | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.52 | .000 *** |

| Negative Emotionality | → Depression | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.75 | .000 *** |

| Negative Emotionality | → Negative Affect | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.77 | .000 *** |

| Negative Emotionality | → Neuroticism | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.81 | .000 *** |

| Healthy Diet | → Beans | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.53 | .000 *** |

| Healthy Diet | → Cruciferous Greens | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.47 | .000 *** |

| Healthy Diet | → Fruit | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.67 | .000 *** |

| Healthy Diet | → Green Leafy Vegetables | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.61 | .000 *** |

| Healthy Diet | → Nuts | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.67 | .000 *** |

| Exercise | → Regular Exercise Program | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.70 | .000 *** |

| Exercise | → Vigorous Activities (Min/Session) | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.79 | .000 *** |

| Exercise | → Vigorous Activities (Times/Wk) | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.74 | .000 *** |

Structural model

The complete model with all structural paths included had an acceptable fit. RMSEA = .046 (95% CI: .045, .048), NFI = .918, CFI = .923, SRMR=.036. As might be expected with such a large sample size the χ2 was statistically significant—χ2 (235) = 3525.28, p<.0005. Table 5 shows the standardized regression weights connecting latent variables in the full model. Most paths were statistically significant at p < .001 though Religious Engagement was not directly related to Exercise or Mortality, nor was Church Activity directly related to Negative Emotionality or Healthy Diet, Negative Emotionality to Mortality, or Healthy Diet to Mortality. Additionally some paths—Positive Religious Support to Exercise, Positive Religious Support to Healthy Diet, and Positive Religious Support to Mortality—were weaker than our cutoff value of p<.001 and so were left out of our final model.

Table 5.

Standardized Structural Model Regression Weights for the All Paths Model

| Variable

|

95% CI

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | → Dependent | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p |

| Religious Engagement | → Church Activity | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.38 | .000 *** |

| Religious Engagement | → Exercise | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.04 | .916 |

| Religious Engagement | → Healthy Diet | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.22 | .000 *** |

| Religious Engagement | → Mortality | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.07 | .225 |

| Religious Engagement | → Negative Emotionality | −0.30 | −0.34 | −0.25 | .000 *** |

| Religious Engagement | → Positive Religious Support | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.45 | .000 *** |

| Church Activity | → Exercise | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.12 | .000 *** |

| Church Activity | → Healthy Diet | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.08 | .056 |

| Church Activity | → Mortality | −0.09 | −0.12 | −0.05 | .000 *** |

| Church Activity | → Negative Emotionality | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.01 | .114 |

| Church Activity | → Positive Religious Support | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.41 | .000 *** |

| Positive Religious Support | → Exercise | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.02 | .009 ** |

| Positive Religious Support | → Healthy Diet | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.11 | .017 * |

| Positive Religious Support | → Mortality | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.10 | .014 * |

| Positive Religious Support | → Negative Emotionality | −0.10 | −0.15 | −0.05 | .000 *** |

| Negative Emotionality | → Exercise | −0.11 | −0.15 | −0.07 | .000 *** |

| Negative Emotionality | → Healthy Diet | −0.12 | −0.16 | −0.08 | .000 *** |

| Negative Emotionality | → Mortality | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.06 | .305 |

| Healthy Diet | → Exercise | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.38 | .000 *** |

| Healthy Diet | → Mortality | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.04 | .884 |

| Exercise | → Mortality | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.04 | .000 *** |

Simplified Model

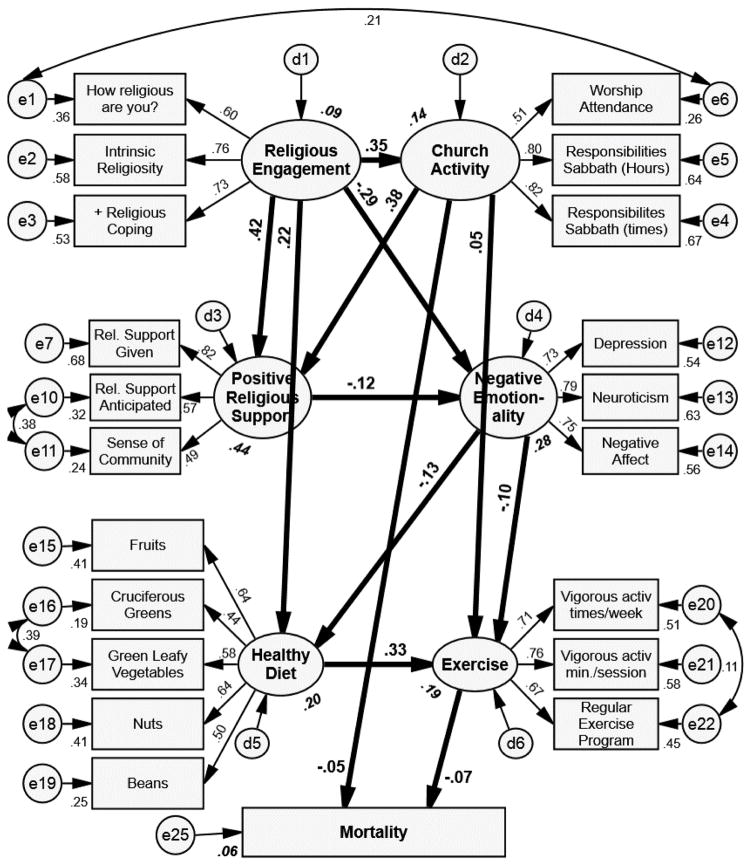

The simplified model is shown in Figure 1 and the fit indices remain similar after the weak paths (p >= .001) were dropped—RMSEA=.046 (95% CI: .044, .047), NFI=.917, CFI=.922, and SRMR=.036. Again, as might be expected with a large sample size, χ2 was statistically significant—χ2 (244) = 3573.89, p<.0005. The biggest change in the fit statistics was a slight tightening of the RMSEA confidence limits. Note, however, that there is again no direct path from Religious Engagement to Mortality. There is however, a direct path from Church Activity to Mortality. There is a strong negative path between Religious Engagement and Negative Emotionality, and a positive path from Religious Engagement to Church Activity, Positive Religious Support and Healthy Diet. Interestingly, Church Activity and Exercise are the only latent variables directly related to lower Mortality.

Figure 1.

Final path model with all latent variable paths with p≥.001 trimmed from the model. Numbers adjacent to a latent variable (ellipse) or manifest variables (rectangles) are the portion of the variance of that variable explained by the other variables connecting to it.

Direct, indirect, and total effects are detailed in Table 6. While only Church Activity, and Exercise, had direct associations all the variables except exercise (which had no indirect paths) had indirect association with mortality. Religious Engagement and Healthy Diet had the strongest indirect effects with both being associated with lower mortality. The strongest total effects on mortality were Exercise, Church Activity, and Religious Engagement all of which were associated with lowered mortality.

Table 6.

Standardized Direct, Indirect, and Total effects for Model leaving out all direct effects with p >= .001

| Religious Engagement

|

Church Activity

|

Positive Religious Support

|

Negative Emotionality

|

Healthy Diet

|

Exercise

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI

|

95% CI

|

95% CI

|

95% CI

|

95% CI

|

95% CI

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Est. | Lower | Upper | p | Est. | Lower | Upper | p | Est. | Lower | Upper | p | Est. | Lower | Upper | p | Est. | Lower | Upper | p | Est. | Lower | Upper | p | |

| Standardized Direct Effects | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Church Activity | .354 | .320 | .387 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pos. Religious Support | .417 | .381 | .451 | .000 | .379 | .346 | .412 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Negative Emotionality | −.295 | −.339 | −.248 | .000 | −.122 | −.166 | −.079 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Healthy Diet | .220 | .183 | .259 | .000 | −.126 | −.165 | −.086 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Exercise | .052 | .021 | .084 | .001 | −.097 | −.133 | −.062 | .000 | .329 | .292 | .365 | .000 | ||||||||||||

| Mortality | −.047 | −.074 | −.020 | .001 | −.072 | −.101 | −.043 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Standardized Indirect Effects | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Church Activity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pos. Religious Support | .134 | .118 | .152 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Negative Emotionality | −.067 | −.092 | −.043. | 000 | −.046 | −.065 | −.030 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Healthy Diet | .045 | .031 | .060 | .000 | .006 | .003 | .010. | 000 | .015 | .009 | .025 | .000 | ||||||||||||

| Exercise | .141 | .122 | .161 | .000 | .006 | .004 | .010 | .000 | .017 | .010 | .025 | .000 | −.041 | −.056 | −.028 | |||||||||

| Mortality | −.027 | −.037 | −.017 | .000 | −.004 | −.008 | −.002 | .000 | −.001 | −.002 | −.001 | .000 | .010 | .006 | .016 | .000 | −.024 | −.034 | −.014 | .000 | ||||

| Standardized Total Effects | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Church Activity | .354 | .320 | .387 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pos. Religious Support | .551 | .519 | .583 | .000 | .379 | .346 | .412 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Negative Emotionality | −.362 | −.394 | −.328 | .000 | −.046 | −.065 | −.030 | .000 | −.122 | −.166 | −.079 | .000 | ||||||||||||

| Healthy Diet | .266 | .232 | .300 | .000 | .006 | .003 | .010 | .000 | .015 | .009 | .025 | .000 | −.126 | −.165 | −.086 | .000 | ||||||||

| Exercise | .141 | .122 | .161 | .000 | .059 | .028 | .090 | .000 | .017 | .010 | .025 | .000 | −.138 | −.174 | −.104 | .000 | .329 | .292 | .365 | .000 | ||||

| Mortality | −.027 | −.037 | −.017 | .000 | −.051 | −.078 | −.024 | .001 | −.001 | −.002 | −.001 | .000 | .010 | .006 | .016 | .000 | −.024 | −.034 | −.014 | .000 | −.072 | −.101 | −.043 | .000 |

In separate analyses (not shown) we found that the model was invariant by gender and by ethnicity.

Discussion

These study findings contribute to our understanding of the relationship between religion and mortality in several ways. The use of a large, national cohort sample of Adventist adults is potentially generalizable to other similar groups. In addition, Adventists’ low rates of substance use/abuse (smoking, use of alcohol) can rule out these health behavior explanations to allow an examination of diet and exercise mediators. This is important because a healthy diet is an overt Adventist doctrinal message while exercise is not. Finally, we were able to test a large model of indirect mediators of the relationships between two aspects of religious life and mortality, as well as the direct relationship between two aspects of religious life and mortality. As such, the primary aim of this study was to combine, in a single model, several competing explanations for the long-recognized religiosity-to-mortality association. The model confirms a direct association between church activity and mortality that is consistent with other literature with age controlled (Hummer, Ellison, Rogers, Moulton, & Romero, 2004; Lee, Stacey, & Fraser, 2003; Strawbridge et al., 1997; Williams & Sternthal, 2007). The model adds to the existing literature by identifying the indirect paths between religious engagement and mortality as church activity, positive social support, negative emotionality, diet, and exercise (i.e., lifestyle) in that order. There were no direct paths between religious engagement and mortality, nor between social support, negative emotionality or diet and mortality. Other than church activity, exercise has the only direct path to mortality.

Our findings add to the existing evidence of the link between religion and mortality by providing an expanded measure of church activity that includes not only the typical worship frequency but also an assessment of church responsibilities and the amount of time spent on them. We find that remaining involved in a church congregation through frequent worship as well as other congregational activities relating to study, teaching, and leadership roles relates directly to mortality.

Religious engagement assessed as religious coping, subjective religiousness, and intrinsic religiosity was not directly predictive of mortality and operated only indirectly through functional and psychosocial mediators. Specifically, religious engagement, as hypothesized for Adventists, had the strongest relationship to mortality through healthy diet and then exercise to mortality. Adventist doctrine includes a message for a vegetarian diet and 42.7% of our participants report that they never or rarely eat red meat, chicken or turkey, or fish (pork is proscribed by the denomination and was not included in the assessment although, if they are rarely or never eating other meats, it is unlikely that pork consumption would appreciably decrease this figure). However, healthy diet did not directly predict mortality. The healthy diet apparently spread to another healthy behavior, exercise, to then indirectly predict mortality. Religious engagement worked through health behavior and through church activity to influence mortality in our sample.

Religious engagement also operated indirectly on mortality via increased positive religious support and reduced negative emotionality that then led to a healthy diet and exercise to, in turn, predict mortality. Interestingly, positive religious support did not predict either diet or exercise behavior directly even though we anticipated that there would be strong social norms within Adventist church communities that supported these health behaviors. Instead, religious engagement predicted less negative emotionality that lead to healthier diet and then exercise. Overall however, religious engagement and healthy diet had the strongest indirect associations with mortality which is consistent with the doctrinal messages of this denomination. Overall, the strongest predictors of mortality were Church Activity (direct), Religious Engagement (indirect), and Exercise (direct). Church activity was positively associated with religious engagement which then operated through all three psychosocial mediators to impact mortality.

Our model had a number of advantages over past study designs. First, we examined both the more intrinsic aspects of religiosity (Religious Engagement) and the more behavior-oriented aspects of religiosity (Church Activity). This is important because, as we saw in our study control variables, church activity was negatively related to age. By including religious engagement as well as church activity levels there is no undue bias against those with advancing age and potentially failing health that might diminish church attendance.

Second, our church activity variable included the typical worship frequency as well as other types of church activities that take time and provide opportunities for leadership within the congregational community. What is quite interesting is that although church activity does operate indirectly through positive social support, negative emotionality, and health behaviors to impact mortality, the main effects of church activity are direct which weakens the claim that church activity operates primarily through support mechanisms (Maselko, Hughes, & Cheney, 2011; Maselko et al., 2007) or primarily through emotional mechanisms that may relate to meaning (Galek, Flannelly, Ellison, Silton, & Jankowski, 2015). Church activity instead may operate directly on biological mechanisms relating to stress reactivity (T. D. Hill, Rote, Ellison, & Burdette, 2014; Maselko et al., 2007).

Third, we examined three of the proposed religion and health mediators including social support, negative emotionality, and lifestyle in one model to more closely approximate the complexity of human experiences in a religious community. We see a complex, interrelated set of religious constructs that mutually reinforce and complement one another, with the links between religious variables with psychosocial mediators leading to healthier behaviors and decreased mortality.

This study tells us a great deal about how Seventh-day Adventism contributes to longer life among its constituents; the question of how these findings might generalize to non-SDA samples, however, is a relevant one. This sample naturally controls smoking and drinking, as very few of the participants in the Adventist Health Study report either smoking or drinking. Thus we might expect that religious groups that restrict smoking and drinking would be similar; for those denominations that have no restrictions on these behaviors we would expect to see the same general patterns, but with a broader set of relevant lifestyle pathways.

This study has several strengths including a large sample size with validated measures of multiple constructs relevant to investigating the religion and health link. In addition, the model was complex enough to test important mediators. Few studies have attempted to test these mediators simultaneously though it is likely that they all do operate together to impact health outcomes. In addition, the outcome of mortality risk was stronger than the typical outcome of self-reported health status that may be confounded with mental health concerns.

This study has a number of limitations. Though the mortality outcome was examined prospectively after the religious and religious mediators were assessed, it is impossible to ascribe causal inferences about these associations as there may be other variables not included in the model. There may for example be personality variables as well as other mental health variables, which are not included in the negative emotionality construct, that influence both mortality risk as well as religious constructs. The generalizability of the study is limited to a single denomination, Seventh-day Adventists, or to other religious groups that have strong health behavior messages. The model should also be tested in other broader groups. Other than mortality, the variables are self-reported and may therefore contain a social desirability bias. Despite these limitations, the results of this study contribute to our understanding of the religion and health relationship by indicating that worship and subjective reports of religiousness both contribute to health; worship directly and religiousness indirectly through psychosocial mediators.

The main conclusion of this investigation is that religious engagement is a complex and multifaceted psychosocial phenomenon that influences both mental health and health behaviors to effect mortality risk. Future investigations should further examine whether church activity operates on biomarkers relating to stress reactivity to influence mortality (T. D. Hill et al., 2014). Data from the BRHS on this question are forthcoming. Overall, religiousness operates in a complex psychosocial and behavioral constellation to impact health and mortality that is above and beyond worship frequency.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (Biopsychosocial Religion and Health Study, 1R01AG026348) and the National Cancer Institute for the parent study (Adventist Health Study 2, 5R01 CA094594). Preliminary findings were presented at the 2014 annual meeting of the Western Psychological Association, Portland, OR.

Contributor Information

Kelly R. Morton, Family Medicine and Psychology

Jerry W. Lee, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University

Leslie R. Martin, Department of Psychology, La Sierra University

References

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, Hays J, Musick M. Abstinence versus alcohol use among elderly rural Baptists: A test of reference group theory and health outcomes. Aging and Mental Health. 2002;6:47–54. doi: 10.1080/13607860120101086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell G, Kahana E, Dilworth-Anderson P. Spirituality and Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors: Stress Counter-balancing Effects on the Well-being of Older Adults. Journal of Religion and Health. 2006;45:587–602. doi: 10.1007/s10943-006-9060-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DE. Religious involvement and social resources: Evidence from the data set "Americans' Changing Lives". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1995;34:259–267. doi: 10.2307/1386771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH. Negative affect as motivation to smoke. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1994;3:33–37. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10769919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Tiffany ST, Obremski KM, Baker TB. Postcessation cigarette use: The process of relapse. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90013-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL, Parks GS, Zimmerman RS, Phillips CM. The role of religion in predicting adolescent alcohol use and problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:696–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler TL, Fraser GE, Beeson WL, Knutsen SF, Herring RP, Chan J, … Jaceldo-Siegl K. Cohort profile: The Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37:260–265. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Califano JA, Jr, Bush C, Chenault KI, Dimon J, Fisher M, Fraser DA, … Leffall LD. So help me god: Substance abuse, religion and spirituality. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. 2001 Retrieved July 3, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH. Religiosity/Spirituality and Mortality A Systematic Quantitative Review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2009;78:81–90. doi: 10.1159/000190791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham W. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:51–67. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Spanovic M, Miller N. Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: A meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:823–853. doi: 10.1037/a0016909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Harris KM, Goenig HG, Han X, Sullivan G, Mattox R, Tang L. Religiosity and decreased risk of substance use disorders: Is the effect mediated by social support or mental health status? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010;45:827–836. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, George LK. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33:46–61. doi: 10.2307/1386636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Tashiro T, Berman M, Steger M, Long J. Correlates of levels and patterns of positive life changes following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, editor. Hostility, coping, and health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Galek K, Flannelly KJ, Ellison CG, Silton NR, Jankowski KRB. Religion, meaning and purpose, and mental health. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2015;7:1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0037887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the Relationships Between Religious Involvement and Health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:190–200. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1303_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum R. Frequency of attendance at religious services and cigarette smoking in American women and men: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:1546–1549. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450120058029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DE, Meador KG, Koenig HG. Measuring Religiousness in Health Research: Review and Critique. Journal of Religion and Health. 2008;47:134–163. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RC, Dew MA, Lee A. The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;116:123–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch LR. Informal support patterns of older African-American and White women: Examining effects of family, paid work and religious participation. Research on Aging. 1991;13:144–170. doi: 10.1177/0164027591132003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward RD, Krause N. Changes in church-based social support relationships during older adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;68:85–96. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Hood RW. Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, Ala: Religious Education Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Burdette AM, Ellison CG, Musick MA. Religious attendance and the health behaviors of Texas Adults. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Ellison CG, Burdette AM, Musick MA. Religious Involvement and Healthy Lifestyles: Evidence from the Survey of Texas Adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;34:217–222. doi: 10.1080/08836610701566993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Rote SM, Ellison CG, Burdette AM. Religious Attendance and Biological Functioning: A Multiple Specification Approach. Journal of Aging and Health. 2014;26:766–785. doi: 10.1177/0898264314529333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt C, Haire-Joshu D, Lukwago S, Lewellyn L, Kreuter M. The role of religiosity in dietary beliefs and behaviors among urgan African American women. Cancer, Culture and Literacy: Supplement to Cancer Control. 2005;12:18–90. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope LC, Cook CC. The role of Christian commitment in predicting drug use amongst church affiliated young people. Mental Health, Religion and Culture. 2001;4:109–117. doi: 10.1080/13674670110048336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Ellison CG, Rogers RG, Moulton BE, Romero RR. Religious Involvement and Adult Mortality in the United States: Review and Perspective. Southern Medical Journal. 2004;97:1223–1230. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146547.03382.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S, Pervin LA, John OP. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2. Guilford Press; 1999. The Big Five Trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives; pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, George LK, Cohen HJ, Hays JC, Larson DB, Blazer DG. The relationship between religious activities and cigarette smoking in older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 1998;53A:M426–M434. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.6.m426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Pargament KI, Nielsen J. Religious coping and health status in medically ill hospitalized older adults. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1998;186:513–521. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199809000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Parkerson GR, Meador KG. Religion index for psychiatric research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:885–886. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group, editor. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging; 1999. Religious Support; pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst JL, Bjorck JP, Tan S. Causal attributions for uncontrollable negative events. Journal of Psychology and Christianity. 2000;19:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Landis BJ. Uncertainty, spiritual well-being, and psychosocial adjustment to chronic illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1996;17:217–231. doi: 10.3109/01612849609049916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson DB, Swyers JP, McCullough ME. Scientific research on spirituality and health: A consensus report. Rockville, MD: National Institute for Healthcare Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Morton KR, Walters J, Bellinger DL, Butler TL, Wilson C, … Fraser GE. Cohort profile: The biopsychosocial religion and health study (BRHS) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38:1470–1478. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Stacey GE, Fraser GE. Social support, religiosity, other psychological factors, and health. In: Fraser GE, editor. Diet, Life Expectancy, and Chronic Disease: Studies of Seventh-day Adventists and Other Vegetarians. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. A short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27:405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Hughes C, Cheney R. Religious social capital: Its measurement and utility in the study of the social determinants of health. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;73:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Kubzansky L, Kawachi I, Seeman T, Berkman L. Religious service attendance and allostatic load among high-functioning elderly. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:464–472. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31806c7c57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Friedman HS, Enders CK, Martin LR. Does devoutness delay death? Psychological investment in religion and its association with longevity in the Terman sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:866–882. doi: 10.1037/a0016366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Hoyt WT, Larson DB, Koenig HG, Thoresen C. Religious involvement and mortality: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology. 2000;19:211–222. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak L, Trocki K, Bond J. Religion and alcohol in the U.S. National Alcohol Survey: How important is religion for abstention and drinking? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton KR, Lee JW, Haviland MG, Fraser GE. Religious Engagement in a Risky Family Model Predicting Health in Older Black and White Seventh-Day Adventists. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2012;4:298–311. doi: 10.1037/a0027553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. Religion and coping: The current state of knowledge. In: Folkman S, editor. The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 269–288. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious Coping Methods as Predictors of Psychological, Physical and Spiritual Outcomes among Medically Ill Elderly Patients: A Two-year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9:713–730. doi: 10.1177/1359105304045366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:710–724. doi: 10.2307/1388152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM. Religious coping among the religious: The relationships between religious coping and well-being in a national sample of Presbyterian clergy, elders, and members. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40:497–513. doi: 10.1111/0021-8294.00073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:707–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00428.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M, Lee Roff L, Klemmack DL, Koenig HG, Baker P, Allman RM. Religiosity and mental health in southern, community-dwelling older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2003;7:390–397. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000150667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick JH, Kinney JM. Why believe? The effects of religious beliefs on emotional well being. Journal of Religious Gerontology. 2003;14:153–170. doi: 10.1300/J078v14n02_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pudrovska T, Schieman S, Pearlin LI, Nguyen K. The Sense of Mastery as a Mediator and Moderator in the Association Between Economic Hardship and Health in Late Life. Journal of Aging and Health. 2005;17:634–660. doi: 10.1177/0898264305279874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Rothman AJ, Detweiler JB, Steward WT. Emotional states and physical health. American Psychologist. 2000;55:110–121. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnall E, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Swencionis C, Zemon V, Tinker L, O'Sullivan MJ, … Goodwin M. The relationship between religion and cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Psychology and Health. 2010;25:249–263. doi: 10.1080/08870440802311322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE. Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration. Annals of Epidemiology. 1996;6:442–451. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Dubin LF, Seeman M. Religiosity/spirituality and health: A critical review of the evidence for biological pathways. American Psychologist. 2003;58:53–63. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:601–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PN, Fraser GE, Knutsen SF, Lindsted KD, Bennett HW. Validity of a physical activity questionnaire among African-American Seventh-day Adventists. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33:468–475. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200103000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PN, Tonstad S, Abbey DE, Fraser GE. Validity of selected physical activity questions in white Seventh-day Adventists and non-Adventists. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1996;28:1026–1037. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199608000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:957–961. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Cohen RD, Kaplan GA. Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;46:51–67. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Church members as a source of informal social support. Review of Religious Research. 1988;30:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Terreri CJ, Glenwick DS. The relationship of religious and general coping to psychological adjustment and distress in urban adolescents. Journal of Religion and Health. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- van Melle JB, de Jonge P, Spijkerman TA, Tijssen JGP, Ormel J, van Veldhuisen DJ, … van den Berg MP. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:814–822. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146294.82810.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Olphen J, Schulz A, Israel B, Chatters L, Klem L, Parker E, Williams D. Religious involvement, social support, and health among African-American women on the East side of Detroit. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:549–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KY, Kercher K, Huang JY, Kosloski K. Aging and Religious Participation in Late Life. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53:1514–1528. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9741-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb AP, Ellison CG, McFarland MJ, Lee JW, Morton K, Walters J. Divorce, religious coping, and depressive symptoms in a conservative protestant religious group. Family Relations. 2010;59:544–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00622.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Larson DB, Buckler RE, Heckmann RC, Pyle CM. Religion and psychological distress in a community sample. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90040-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Sternthal MJ. Spirituality, religion and health: evidence and research directions. Medical journal of Australia. 2007;186:S47. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]