Highlights

-

•

Mediastinal paragangliomas are extremely rare and their diagnosis and management can be challenging.

-

•

These tumors are classified as functional or non-functional according to their ability to produce and release catecholamines.

-

•

Appropriate laboratory studies should be done prior to biopsy or surgical resection to avoid complications.

-

•

Complete surgical resection continues to be the standard of care for patients diagnosed with mediastinal paraganglioma.

-

•

Surgeons must consider catecholamine-secreting tumors as a differential diagnosis of mediastinal lesions.

Keywords: Paraganglioma, Mediastinum, Surgery, Management, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Paragangliomas are neuroendocrine tumors arising from chromaffin cells located in sympathetic paraganglia. Mediastinal paragangliomas are extremely rare and can be classified as functional or non-functional according to their ability for secreting catecholamines. Patients can be asymptomatic and the diagnosis is usually incidental. Complete surgical resection remains the standard of care for paragangliomas.

Presentation of case

We present a 44-year-old woman with a functional mediastinal paraganglioma incidentally found during the perioperative imaging workup for a diagnosed breast carcinoma. Chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT) showed a well-defined lesion in the posterior mediastinum suspicious for an esophageal malignancy. Endoscopic and CT-guided biopsies were performed confirming the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor. Laboratory studies showed elevated catecholamines and chromogranin A levels, consistent with a paraganglioma. Appropriate pre-operative management was done and successful surgical resection without catecholamine related complications was achieved.

Discussion

The workup and treatment of incidentally discovered adrenal and extra-adrenal lesions are controversial. Because of the absence of symptoms and the wider differential diagnosis of extra-adrenal lesions, an attempt for biopsying and surgically remove these lesions prior to biochemical testing is not an uncommon scenario, although this could be potentially harmful. Surgeons should have an index of suspicion for catecholamine-secreting tumors and hormonal levels should be assessed prior to biopsy or surgical resection.

Conclusion

Surgeons should consider paragangliomas as a differential diagnosis for extra-adrenal lesions. Biochemical testing with catecholamines and chromogranin A levels should be performed prior to biopsy or surgical removal in order to avoid catastrophic complications.

1. Introduction

Paragangliomas are uncommon neuroendocrine tumors originating from chromaffin cells located in extra-adrenal sympathetic ganglia. Whereas ninety percent of adrenergic tumors originate in the adrenal medulla and are known as pheochromocytomas, the remaining 10% are extra-adrenal and are called paragangliomas [1]. The incidence of paragangliomas has been reported to be between 2–8 cases per million people yearly [2], although autopsy series have shown higher prevalence suggesting that a considerable number of these tumors are not diagnosed during life [3]. Paragangliomas, also called extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas, are classified as functional or non-functional according to their ability to produce and release catecholamines [4]. Paragangliomas can be found in a number of locations including the abdomen (80–95%), pelvis and head and neck (5%), and in the thoracic cavity (10%) [1], [5]. Paragangliomas occurring in the mediastinum are extremely rare and account for only 1–2% of all paragangliomas and less than 0.3% of all mediastinal tumors [6], [7]. Mediastinal paragangliomas can originate in the anterior and posterior mediastinum where they arise from para-aortic and para-vertebral sympathetic ganglia respectively [8], [9]. Between 50%–80% of the patients with paragangliomas are asymptomatic and the diagnosis is usually incidental or related with the mass affect caused by the tumor [8], [10], [11]. Complete surgical resection is the standard of care for patients diagnosed with paraganglioma. However, surgeons must consider catecholamine-secreting tumors as a differential diagnosis, and the appropriate laboratory studies should be done prior to any biopsy attempt or surgical removal in order to avoid the devastating complications associated with tumor sampling and manipulation [12].

2. Presentation of case

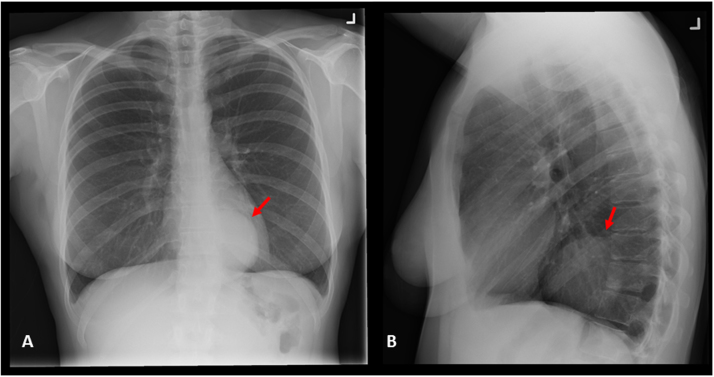

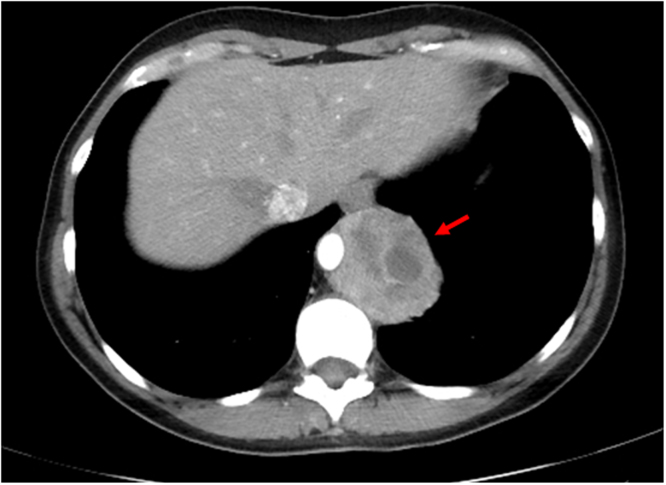

A 44-year old woman with history of lupus and asthma underwent a partial mastectomy for a cT1N0 infiltrating ductal breast carcinoma diagnosed by mammography. A perioperative chest radiograph was notable for a large posterior mediastinal mass (Fig. 1). On chest computed tomography (CT) scan, a 5 × 6.4 cm posterior mediastinal mass encasing the distal esophagus and the aorta was evidenced (Fig. 2). Due to the suspicion for an esophageal tumor, an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and fine needle aspiration were done which suggested a sarcoma. After review by a multidisciplinary team and due to the concern for an inaccurate diagnosis, a CT-guided core biopsy was performed giving the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor. At this point it was decided to perform laboratory studies. Markedly elevated plasma metanephrines (2.55 nmol/L, normal < 0.45 nmol/L), normetanephrines (55.8 nmol/L, normal < 0.89 nmol/L) and an elevated chromogranin A level of 2969 ng/mL (normal < 50 ng/mL) confirmed the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor. 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy supported the diagnosis of a solitary neuroendocrine tumor consistent with a paraganglioma.

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray. (A) Posteroanterior and (B) lateral views showing a well circumscribed opacity (arrow) located in the posterior mediastinum.

Fig. 2.

Chest computed tomography. Hypodense mass (arrow) measuring 5 × 6.4 cm encasing the distal esophagus and aorta.

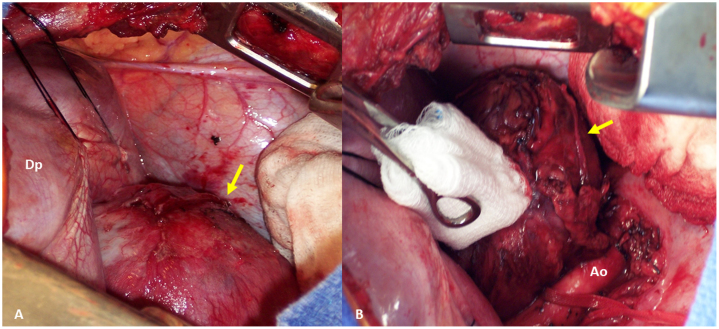

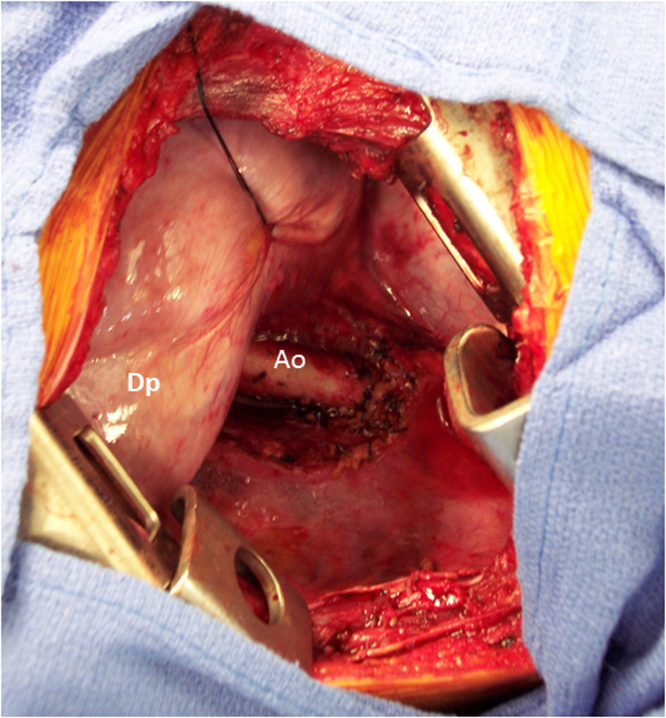

The patient remained asymptomatic. Preoperative preparation involved increasing doses of phenoxybenzamine, a non-selective alfa blocker, salt and volume loading and daily communication with the patient over the two weeks of medical treatment. The patient was taken to the operating room. Intra-operative monitoring included an arterial line and urinary catheter. A left posterolateral thoracotomy in the seventh intercostal space was performed. The mass was easily identified above the diaphragm and abutting the aorta (Fig. 3). The left lower lobe was adherent to the mass requiring a small wedge resection of lung. The inferior pulmonary ligament was divided. The mass abutted but did not invade the esophagus, however it was encompassing fifty percent of the aortic wall. The mass was dissected off the aorta and freed from the esophagus with liberal clipping and tying of ample vascular supply (Fig. 4). The patient maintained hemodynamic stability throughout the dissection. The tumor was excised in entirety without capsular disruption. The estimated blood loss was 150 mL and operative duration was 150 min. The extubated patient was observed in intensive care overnight and discharged home on postoperative day 3. The excised mass had a maximum diameter of 7.5 cm (Fig. 5) and the histological diagnosis was consistent with a paraganglioma. Post-operative metanephrine, normetanephrine and chromogranin A levels obtained two weeks postoperatively were normal at 0.11 nmol/L, 0.27 nmol/L and 42 ng/mL respectively. Genetic testing for all of the succinyl dehydrogenase mutations was done and the results were negative. After five years of follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic with no signs of disease and normal metanephrine levels.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative view. (A) Well defined encapsulated mass (arrow) identified above the diaphragm (Dp). (B) Dissection and resection of the mass (arrow) abutting the aorta (Ao).

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative view after surgical resection. Aorta (Ao), Diaphragm (Dp).

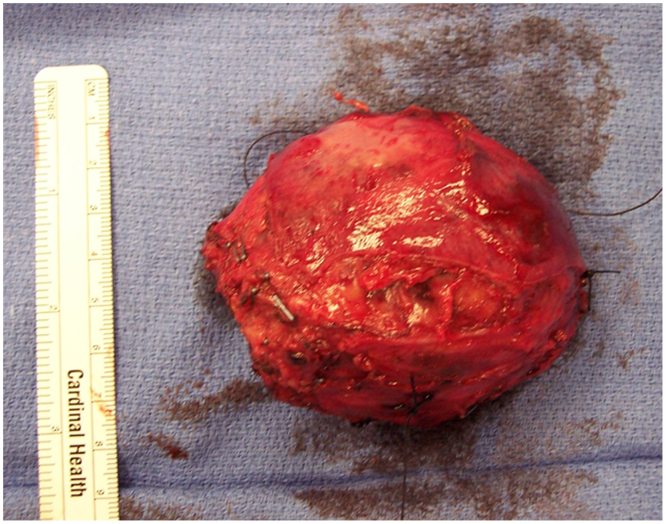

Fig. 5.

Macroscopic view of the 7.5 cm resected mass.

3. Discussion

The workup and treatment of incidentally discovered lesions of the adrenal gland and sympathetic paraganglia are a controversial topic. With the incidence of these “incidentalomas” on the rise due to more frequent use of cross-sectional imaging, an increase body of literature is evaluating the most effective ways to go about evaluating these lesions safely [12], [13], [14], [15]. Less is written regarding the safe workup of extra-adrenal lesions which may be paragangliomas. Mediastinal paragangliomas are rare but should remain in the differential when considering preoperative needle biopsies by endoscopic, bronchoscopic or radiologic guidance.

Testing of serum biochemical markers (metanephrines, normetanephrines and chromogranin A) is the preferred initial workup for lesions suspicious for being pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas [13]. Biopsy of these lesions is potentially dangerous to the patient, occasionally causing life-threatening alterations in hemodynamics following the biopsy, as well as increasing the difficulty of eventual surgical resection [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Because of the wider differential diagnosis of extra-adrenal lesions, and their low likelihood of being hormonally active, they may be more likely to be biopsied prior to biochemical evaluation. However, this is potentially harmful [16]. One series reported rates of complications related to biopsy of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas in as high as 70% of cases [12]. As it is now common to perform endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided (EBUS and EUS) fine needle aspirations (FNA) of mediastinal masses, caution is suggested.

This patient had a functional paraganglioma with elevated serum metanephrines and chromogranin A levels, although she was asymptomatic. The level of suspicion for a paraganglioma prior to biopsy was absent. The risk of precipitating a hypertensive crisis while biopsying an adrenal or extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas is well documented. In the era of EBUS and EUS guided-FNAs of mediastinal and adrenal masses in thoracic surgery patients, it is important to have an index of suspicion for a catecholamine-secreting lesion. Surgeons should be reminded that up to 40% of patients with pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are entirely asymptomatic, and that prior to any biopsy attempt biochemical screening with serum catecholamines and chromogranin A levels is recommended for any adrenal tumor or any mass located in the sympathetic paraganglia.

4. Conclusion

Mediastinal paragangliomas are extremely rare tumors that can arise in the anterior and less commonly in the posterior mediastinum. Most paragangliomas are not functional and a diagnosis based on their secretory properties could be challenging. We presented a case of an asymptomatic but functional paraganglioma located in the posterior mediastinum that was discovered incidentally as part of the perioperative imaging studies for the patient’s primary breast cancer. Because of the absence of symptoms in the majority of cases, the wider differential diagnosis of extra-adrenal lesions, and their low likelihood of being hormonally active, is not uncommon to proceed with biopsy sampling prior to biochemical testing, which could lead to catastrophic complications. Surgeons must consider paragangliomas as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with extra-adrenal and mediastinal masses. Biochemical screening with serum fractionated metanephrines and chromogranin A levels should be performed prior to any biopsy or surgical attempt in order to avoid undesired complications.

*This case report has been written in line with the SCARE criteria [17].

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval required.

Consent

Consent was obtained from the patient and identifying labels were omitted.

Authors contribution

Juan A. Muñoz-Largacha: Study design, analysis and interpretation of data, paper writing and final approval.

Roan Glocker: Study design, data collection and interpretation, paper writing and final approval.

Jacob Moalem: Study design, data collection and interpretation, paper writing and final approval.

Michael J. Singh: Study design, data collection and interpretation, paper writing and final approval.

Virginia R. Litle: Conception and study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, paper writing and final approval.

Guarantor

Virginia R. Litle.

References

- 1.Gunawardane P.T., Grossman A. Phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;(November) doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_76. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stenström G., Svärdsudd K. Pheochromocytoma in Sweden 1958–1981: an analysis of the national cancer registry data. Acta Med. Scand. 1986;220(3):225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald P.A. Chapter 11. Adrenal medulla and paraganglia. In: Gardner D.G., Shoback D., editors. Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soffer D., Scheithauer B.W. Paraganglioma. In: Kleihues P., Cavenee W.K., editors. Patholopy and Genetics of Tumours of the Nervous System. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2000. pp. 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whalen R.K., Althausen A.F., Daniels G.H. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma. J. Urol. 1992;147:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drucker E.A., McLoud T.C., Dedrick C.G., Hilgenberg A.D., Geller S.C., Shepard J.A.O. Mediastinal paraganglioma: radiologic evaluation of an unusual vascular tumor. AJR. 1987;148:521–522. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takashima Y., Kamitani T., Kawanami S., Nagao M., Yonezawa M., Yamasaki Y. Mediastinal paraganglioma. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2015;33(July (7)):433–436. doi: 10.1007/s11604-015-0436-z. Epub 30 May 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young W.F., Jr. Paragangliomas: clinical overview. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;1073:21–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1353.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balcombe J., Torigian D.A., Kim W., Miller W.T., Jr. Cross-sectional imaging of paragangliomas of the aortic body and other thoracic branchiomeric paraganglia. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007;188:1054–1058. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wald O., Shapira O.M., Murar A., Izhar U. Paraganglioma of the mediastinum: challenges in diagnosis and surgical management. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2010;5(March):19. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzawa K., Yamamoto H., Ichimura K., Toyooka S., Miyoshi S. Asymptomatic but functional paraganglioma of the posterior mediastinum. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014;97(March (3)):1077–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderveen K.A., Thompson S.M., Callstrom M.R., Young W.F., Jr., Grant C.S., Farley D.R. Biopsy of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: potential for disaster. Surgery. 2009;146(December (6)):1158–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzaglia P., Monchik J. Limited value of adrenal biopsy in the evaluation of adrenal neoplasm. Arch. Surg. 2009;144(5):465–470. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casola G., Nocolet V., vanSonnenbery E., Withers C., Bretagnolie M., Saba R.M. Unsuspected pheochromocytoma: risk of blood-pressure alterations during percutaneous adrenal biopsy. Radiology. 1986;159:733–735. doi: 10.1148/radiology.159.3.3517958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford J., Rosenberg F., Chan N. Pheochromocytoma manifesting with shock presents a clinical paradox: a case report. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1997;157:923–925. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalal T., Maher M.M., Kalra M.K., Mueller P.R. Extraadrenal pheochromocytoma: a rare cause of tachycardia and hypertension during percutaneous biopsy. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005;185(August (2)):554–555. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34(October):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]