Abstract

DNA polymerase (Pol) β maintains genome fidelity by catalyzing DNA synthesis and removal of a reactive DNA repair intermediate during base excision repair (BER). Situated within the middle of the BER pathway, Pol β must efficiently locate its substrates before damage is exacerbated. The mechanisms of damage search and location by Pol β are largely unknown, but are critical for understanding the fundamental features of the BER pathway. We developed a processive search assay to determine if Pol β has evolved a mechanism for efficient DNA damage location. These assays revealed that Pol β scans DNA using a processive hopping mechanism and has a mean search footprint of ∼24 bp at predicted physiological ionic strength. Lysines within the lyase domain are required for processive searching, revealing a novel function for the lyase domain of Pol β. Application of our processive search assay into nucleosome core particles revealed that Pol β is not processive in the context of a nucleosome, and its single-turnover activity is reduced ∼500-fold, as compared to free DNA. These data suggest that the repair footprint of Pol β mainly resides within accessible regions of the genome and that these regions can be scanned for damage by Pol β.

INTRODUCTION

Maintenance of genome integrity is essential for cellular survival. The base excision repair (BER) pathway functions in repairing damaged or aberrant DNA bases. In general, the pathway is initiated by glycosylases catalyzing the removal of damaged bases, forming abasic sites (1). The resulting abasic sites are 5΄ incised by APE1 generating 5΄ deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) groups (2) that are removed by Pol β via its 8-kDa lyase domain (3,4). Pol β also catalyzes gap-filling DNA synthesis and the resulting nicks are ligated by DNA ligase (5–7). Due to the potential reactivity of the abasic site and dRP group, it has been proposed that the BER pathway is highly coordinated (8–10). Since Pol β is centrally located within the pathway and removes a potentially toxic intermediate, its ability to locate substrates in a timely manner is required to prevent cell death or mutations. Given that Pol β substrates are embedded within a DNA polymer and scattered throughout the entire genome, we hypothesized that Pol β has evolved unique mechanisms of searching and/or recruitment to efficiently find DNA substrates.

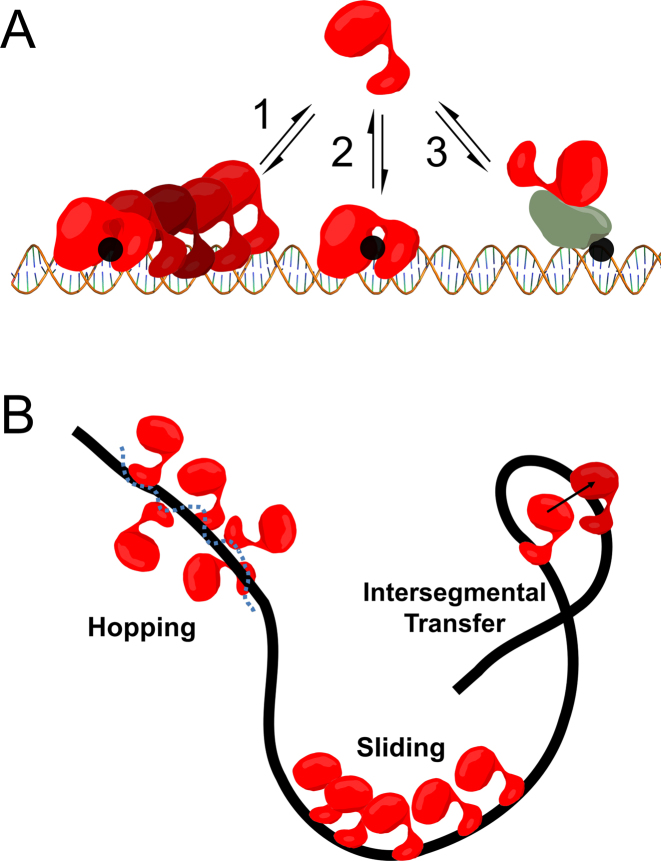

Three models of damage location by Pol β have been proposed (Figure 1A). In one model, Pol β undergoes random 3D diffusion, where site location depends on direct binding to damage. Random diffusion through bulk solution is predicted to be an inefficient mechanism of target site location in genomic DNA at low protein concentrations (11). In a second model, Pol β localizes to damage through a protein recruitment mechanism, whereby a Pol β binding partner first recognizes the damage and then recruits Pol β via protein–protein interactions or post-translational modifications. In the last model, Pol β can bind non-specifically to DNA and translocate in either direction by thermal diffusion, thereby using the DNA polymer as a conduit to facilitate damage localization. This mechanism is termed facilitated diffusion or processive searching, and many DNA-binding proteins involved in nucleotide excision repair, transcription initiation, mismatch repair and DNA glycosylases involved in base excision repair are proposed to use this mechanism (12–14). These models are not mutually exclusive, however the degree to which Pol β uses these mechanisms to accomplish BER, if at all, is unknown.

Figure 1.

Models of Pol β DNA damage location. (A) DNA damage (i.e. 1-nt gaps) are shown as black circles. Model 1 depicts facilitated diffusion which involves Pol β using DNA as a conduit to locate damage. Although depicted as directional for brevity, facilitated diffusion is stochastic. Model 2 represents 3D diffusion, where Pol β damage location depends on random and direct collisions with substrate. Pol β recruitment by protein-protein interactions is represented in model 3. (B) Three modes of facilitated diffusion.

Facilitated diffusion can be decomposed into three mechanisms: hopping, sliding, and intersegmental transfer (Figure 1B) (12). Intersegmental transfer involves the direct transfer of a protein from one DNA strand to another through a bridging intermediate or a transient capture event (12,15). Sliding involves the movement of the protein with continual contact with a single DNA backbone, through interactions with the phosphates. In contrast, hopping involves searching of both DNA strands. This is accomplished by the protein undergoing microscopic dissociation/reassociation events with the DNA such that the protein may reorient and land on the opposite strand during a transient excursion (12,16). The net consequence of both sliding and hopping is to essentially increase the DNA binding footprint of a protein.

To determine if Pol β employs facilitated diffusion for damage location, a workflow was developed that correlates two successive nucleotide insertion events within the same DNA strand. Using this method, we show that Pol β can scan DNA in search of DNA damage. Pol β employs an ionic strength-dependent hopping mechanism during the search process. Mutational analysis reveals that the positively charged lyase domain is involved in the processive search, uncovering a novel function of this domain. The catalytic prowess and fidelity of a DNA repair enzyme means little if its ability to locate damage is inefficient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA substrates

DNA oligos were from IDT and were either HPLC (FAM-labeled) or PAGE (unlabeled) purified. The DNA sequences can be found in Supplementary Data.

Enzymes

Wild-type (Wt) and mutant Pol β enzyme were prepared as previously described (17,18). The concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 23 380 M−1 cm−1. The Pol β concentrations reported throughout reflect the value determined by this method. Escherichia coli DNA ligase was from New England Biolabs (NEB).

Processive assays

The processive assays contained 500 nM processive substrate, 1 nM Pol β (as calculated from the extinction coefficient), 50 μM dCTP, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, (37°C), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 10% glycerol (reaction buffer) and varying concentrations of KCl or NaCl as indicated. Reactions were initiated by addition of Pol β into a substrate mix containing 500 nM DNA substrate, 50 μM dCTP (final concentrations after Pol β addition), and incubations were at 37°C. Time points (5.5 μl) were drawn and quenched into 10 μl of 30 mM EDTA, pH 7.5. Then 7 μl of the quenched reaction was transferred to a new tube and 200–500 μM dCMPNPP (Jena Bioscience), 15 mM MgCl2, 1× E. coli ligase buffer, and 0.7 μM E. coli ligase (final concentrations) were added sequentially. The non-hydrolyzable tight-binding inhibitor, dCMPNPP, is added to inhibit DNA polymerization catalyzed by Pol β during the ligation reaction. Ligase reactions were incubated at room temperature for at least 30 min before quenching with 7 μl of 2× quench buffer (200 mM EDTA, 80% formamide, ∼0.1% bromophenol blue, ∼0.1% xylene cyanol). Reaction mixtures were then diluted 5-fold with 95% formamide, heated at 95°C for 5 min, placed on ice and loaded (∼1.1 × 10−13 mol) onto a pre-ran 22% denaturing PAGE. Gels were scanned using a Typhoon scanner and quantified using Imagequant TL (rolling ball method). The concentration of product was calculated by multiplying the fraction product of a given species by the concentration of substrate (500 nM). Initial velocities (V0) were determined by linear fitting the first 10–15% of product formation. The kcat was calculated by dividing the initial velocity for total product formation (total P = A’B + B’C + A’B’C) by the active concentration of Pol β (Supplementary Figure S2). The term kcat is used here because both DNA and dCTP are at saturating concentrations (KM for dCTP is 0.4 μM and the Kd for DNA is ∼30 nM) (19,20). The kcat values are comparable to previous measurements (19). If ligation reactions do not go to completion a +1 nucleotide product will be visible on the gel. Furthermore, E. coli ligase is unable to ligate 1-nt gapped substrates as observed by the zero time-point of the reaction, in contrast to DNA Quick Ligase (NEB).

The fraction processive was calculated by dividing the initial velocity for processive product formation by all enzymatic events (Equation 1) (21):

|

(1) |

The observed fraction processive can also be expressed as (Equation 2) (22):

|

(2) |

Where ksearch is the rate constant describing the translocation of Pol β across non-specific DNA, koff is the rate constant for Pol β dissociating from DNA, and E is the efficiency (Equation 3) (22):

|

(3) |

The fraction processive dependence on ionic strength was fit to a hyperbola (Equation 4) (21):

|

(4) |

where I is the ionic strength concentration, n is the Hill coefficient, Fp,,max is the maximal Fp value, ΔFp is the amplitude and Fp,1/2 the ionic strength concentration at which 50% of the Pol β molecules successfully translocate to the second site. The ionic strength was calculated by taking into account: 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4 (I = 35 mM using the Benyon online calculator), 5 mM MgCl2 (I = 15 mM), and indicated concentrations of KCl or NaCl.

Single-turnover assays

The single-turnover assays were performed with 1 μM Pol β, 50 nM 1-nt standard gap substrate, 50 μM dCTP in reaction buffer at 37°C. Samples were resolved by 22% denaturing PAGE and quantified by ImageQuant TL. Plots of fraction product vs time were fit to a single-exponential equation. The kpol values are in good agreement with previous measurements (19).

Site-spacing dependence

Processive measurements were performed as described above. The plot of Fp/E versus site-spacing were fit to a sliding equation (Equation 5) (23,24):

|

(5) |

Ps is the probability to slide and n is the bp difference between the sites. The data were also fit to a hopping equation (Equation 6) (24):

|

(6) |

where a is the area of the diffusional encounter and r is the distance separating the two sites.

Nucleosome core particle reconstitution

Nucleosomes were generated as generally described (25). Details provided in Supplementary Information.

Pol β catalyzed nucleotide insertion on NCP substrate

The concentration of Pol β required to monitor product formation within a reasonable time-course was first established (Supplementary Figure S7). Multiple-turnover processivity assays with the NCP substrate were performed with 20 nM Pol β, 500 nM NCP and 50 μM dGTP, in reaction buffer containing either 10 mM KCl or 100 mM KCl in a final reaction volume of 12 μl. A substrate mix containing NCP and dGTP was incubated at 37°C for 15 min before initiating the reaction with Pol β that had been incubated at 37°C for 5 min. An aliquot of 0.8 ul of the reaction mixture was quenched into 50 μl of 30 mM EDTA. An aliquot (30 μl) of this solution was then mixed with 60 μl of phenol–chloroform in a phase lock tube and centrifuged following the manufacturer's instructions. The aqueous layer was extracted and diluted 10-fold into H2O, to a final volume of 10 μl. This solution was processed by the sequential addition of 300 μM dGMPCPP, 25 mM MgCl2, 1× ligase buffer and ∼0.5 μM E. coli ligase (final concentrations). The ligation reaction was incubated at room temperature for 30 min before quenching with an equal volume of 2× quench reagent. The reaction products were then separated on a 22% denaturing PAGE and exposed to a phosphoimaging screen (Supplementary Figure S8). Processive assays in 601 DNA (Supplementary Figure S8) were performed as described above for the FAM-labeled processive substrates.

Single-turnover assays with the NCP substrate were performed with 50 nM NCP, 2 or 8 μM Pol β, 50 μM dGTP, and reaction buffer with 100 mM KCl at 37°C. Time points were collected manually and analyzed as described above for the other single-turnover assays (Supplementary Figure S9).

RESULTS

Development of a processive search assay for DNA Pol β

To determine if Pol β conducts facilitated diffusion to locate substrate sites in DNA, we employed a similar method for detection of processivity as that used previously for glycosylases and nucleases (21,22,26). In this assay, two 1-nt gaps are embedded within a DNA duplex and are used for the detection of correlated Pol β enzymatic activity. After Pol β catalyzes nucleotide insertion at one site, forming an intermediate, Pol β either can translocate to the second site without macroscopic dissociation or diffuse into bulk solution. The concentration of DNA substrate must remain high in these assays such that the probability of Pol β rebinding to the intermediate is low. This allows for the measurement of Pol β activity in a single binding event to a DNA molecule. To ensure these conditions, assays contained 1 nM Pol β and 500 nM processive substrate (1:500 ratio). Initial characterization of processivity was performed with a processive DNA substrate that includes a 20 bp spacer between the 1 nt gaps (P20), with an overall length of 57 nt. This substrate also contains the same 8 bp sequence around each insertion site, such that the sites are equivalent, and the substrate includes FAM labels on both the 5΄ and 3΄ ends of the non-template strand.

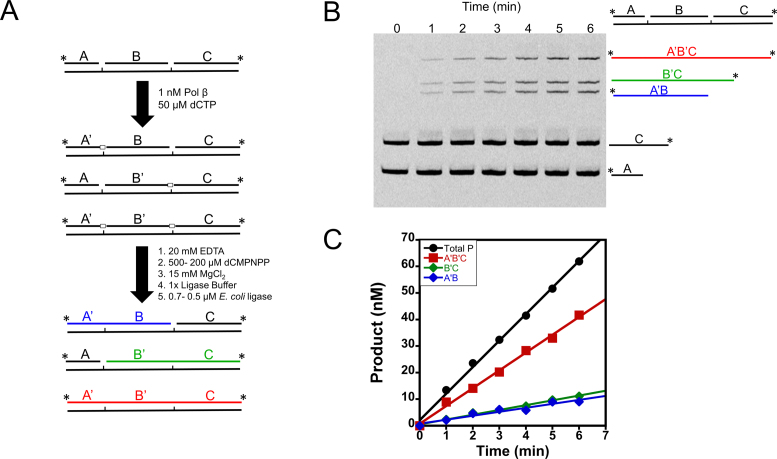

Although this processive assay is similar in principle to previous processive assays employed, it does not allow for correlation of enzymatic activity within the same DNA strand by gel electrophoresis analysis. This is because the substrates and products are gaps or nicks, respectively. Thus, the workflow developed allows for detection of insertion events within the same potential DNA strand (outlined in Figure 2A) through use of product ligation. In this workflow, Pol β catalyzes 1-nt insertions for varying times before quenching with EDTA; the reaction mixture is then incubated with ligase to seal Pol β catalyzed nucleotide insertions. Since both DNA polymerization and ligation are Mg2+ dependent, Pol β was inhibited by the addition of the non-hydrolyzable nucleotide analog 2΄-deoxycytidine-5΄-[(α,β)-imido]triphosphate (dCMPNPP) (Supplementary Figure S1), during the course of the ligation reactions. Reactions are then quenched with EDTA and formamide and products are resolved by denaturing-PAGE (Figure 2B). This workflow allows for the visualization of bands that correspond to distributive action of Pol β, forming intermediates (A’B and B’C), and for processive action (A’B’C) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Processive assay work-flow. (A) Processive assay design. Reactions are initiated by addition of Pol β, terminated with EDTA, and products ligated. Further reaction details are described in the Materials and Methods. Pol β nucleotide insertions are indicated by open boxes and by a prime designation to the respective DNA species (i.e. A to A’). (B) Representative gel of a processive reaction performed at an ionic strength of 150 mM. Time points are indicated above the lanes. The processive product is shown in red (A’B’C) and the intermediates in blue and green (A’B and B’C). (C) Representative initial velocity plot performed at 60 mM ionic strength. The products are color coded as in A and B.

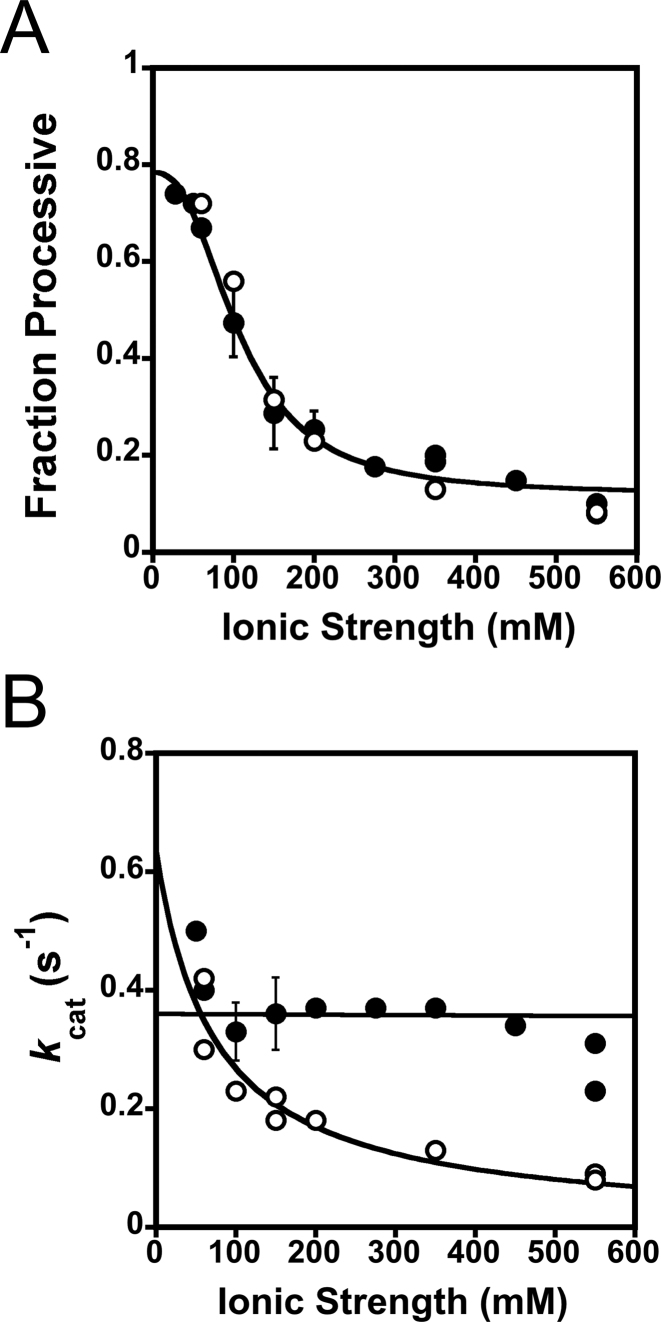

Pol β employs an ionic strength dependent processive search

Visual inspection of Figure 2B reveals that Pol β can catalyze nucleotide insertion at both sites on the processive DNA substrate within a single DNA binding encounter (product band for A’B’C’). The intermediates (A’B and B’C) are also formed. In order to quantify processivity we used the term fraction processive (Fp). The fraction processive is the probability of Pol β to translocate from the first encountered 1-nt gap to the second 1-nt gap within the same DNA molecule, as monitored by polymerase activity. The initial velocities (Vo) for product formation (A’B, B’C and A’B’C) are used to calculate the Fp (Equation 1). A Fp value of one means every time Pol β catalyzes nucleotide insertion at one site it will always translocate to the second site to catalyze nucleotide insertion. Whereas a Fp value of zero means that Pol β never translocates to the second site after catalysis at the first encountered site. The initial velocity plot reveals that each site reacts with the same probability, as expected given the identical sequence context (i.e. A’B and B’C have similar slopes) (Figure 2C). The effect of ionic strength on the Fp was quantified at various KCl and NaCl concentrations (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S1). The Fp decreases hyperbolically with increasing ionic strength (Equation 4) and has a similar dependence on NaCl as KCl (Figure 3A). However, a slight decrease in kcat is observed between KCl and NaCl with increasing ionic strength (Figure 3B). The kcat values for the reactions containing KCl remain largely unchanged over the ionic strength range examined indicating that the rate-limiting step does not change and the decrease in Fp with increasing ionic strengths is not due to a decrease in turnover. Similarly, the kpol, the observed single-turnover rate constant for polymerization at saturating nucleotide and DNA, is only modestly affected by changes in ionic strength (Supplementary Figure S3). The kpol is about ∼5-fold higher than the kcat indicating that kcat is at least partially rate-limited by a step after chemistry, likely a step involved in product release (27). Taken together these data provide evidence that the high level of processivity observed at low ionic strength is not an artifact from rebinding events to intermediates and that the search process involves electrostatic interactions between DNA and Pol β.

Figure 3.

Processivity is ionic strength dependent. (A) Fraction processive values were measured at indicated ionic strengths (as described in Figure 2) and are fit to a hyperbola (Equation 4), yielding a Fp,1/2 of 110 ± 10 mM, and a maximal Fp value (Fp,max) of 0.78 ± 0.05. Reactions performed in KCl are represented in closed circles and NaCl in open circles. The mean and standard deviation from three independent experiments are shown for ionic strengths of 100, 150 and 200 mM in KCl. (B) A plot of kcat versus ionic strength in both KCl and NaCl. The mean and standard deviation for 100, 150 and 200 mM ionic strengths from three independent experiments are shown for the KCl experiments.

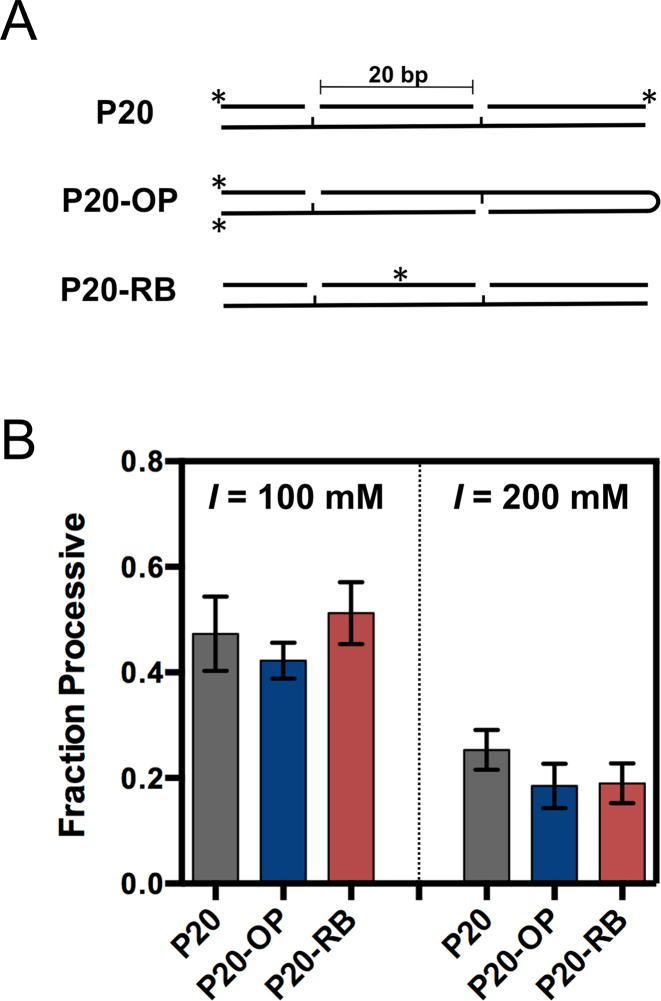

Polymerase β uses a hopping search mechanism

Having established that Pol β uses facilitated diffusion, we determined which of the three intrinsic mechanisms of facilitated diffusion Pol β employs during DNA searching. As described in Figure 1B, there are three main modes of facilitated diffusion (the extent to which Pol β uses intersegmental transfer was not examined here). To test if sliding occurs between gaps, 1-nt gaps were positioned on opposite DNA strands with a spacing of 20 bps (P20-OP) (Figure 4A). If sliding occurs, then the Fp will significantly decrease with this substrate because Pol β will dissociate off the DNA ends before encountering the second 1-nt gap. However, if Pol β uses a hopping mechanism, it will be able to reorient upon dissociating and associating, thereby interrogating both strands of DNA, and resulting in an unaffected Fp. The data in Figure 4B show that the Fp with the P20-OP (1-nt gap on opposite strand) is similar to P20 (same strand) at 100 mM and 200 mM ionic strength, suggesting that Pol β uses a hopping search mechanism.

Figure 4.

Pol β searches DNA using a hopping mechanism. (A) The Fp values for substrates containing 1-nt gaps on opposing strands (P20-OP) and with a small molecule roadblock (P20-RB) are compared to a substrate with 1-nt gaps on the same strand (P20). (B) The Fp values were measured at 100 mM and 200 mM ionic strengths. The mean and standard deviation is reported from three independent experiments.

To further test the sliding and hopping mechanisms a ‘roadblock DNA substrate’ was created that contains a fluorescein group covalently attached within the middle of the spacer region via a phosphorothioate linkage (28). Because the roadblock originates from the non-bridging oxygens of the phosphate backbone, it should block a protein that moves by interacting with the phosphate backbone. Introduction of this roadblock into the P20 spacer region (P20-RB) had no significant effect on the Fp at 100 and 200 mM ionic strength, as compared to the P20 substrate (Figure 4B). Thus, if sliding does occur it must happen within the bp distance of the 1-nt gap and fluorescein group, a distance of ∼10 bp or less.

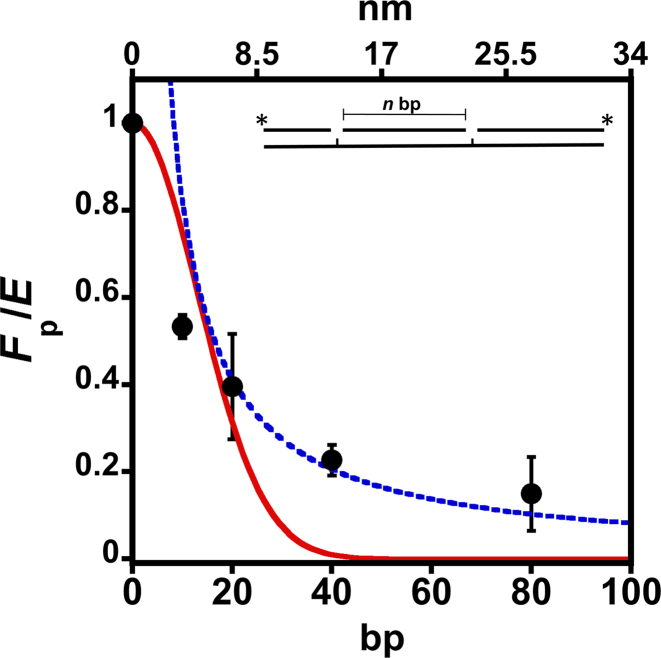

Length dependence of searching

Next, we determined the distance over which Pol β can search to find DNA damage. Additionally, determining the distance dependence of Fp will provide further data to distinguish between models of sliding and hopping. The spacing distance was varied from 10, 20, 40 and 80 bps and the Fp was determined at an ionic strength of 150 mM (near predicted physiological ionic strength) (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S2). As expected, a plot of Fp normalized by efficiency (E) (Supplementary Figure S4) reveals that smaller site spacing distances have higher processive values than longer site spacing. Fitting to a hyperbolic equation yields a half-maximal value (Fp,1/2) of 12 ± 1 bp (i.e. 50% of the Pol β molecules search up to ∼12 bp) (Supplementary Figure S5A). The efficiency is the probability of Pol β to catalyze nucleotide insertion vs. dissociating from the substrate and therefore is used to correct for the fraction of Pol β molecules that reach the second site but dissociate before catalyzing nucleotide insertion (Supplementary information and Figure S4) (22). To determine if the distance dependence of Fp could be explained by a sliding or hopping model, the data were fit to Equations (5) and (6), respectively. The red line shows the best fit to a sliding model and fails to accurately model the data. In contrast, the hopping equation models the data well at longer site spacing and more poorly at smaller site spaces, consistent with proposals of sliding occurring over shorter distances (22,29). The slope from a reciprocal plot of (1/<r>) versus Fp (Supplementary Figure S5B) yields a value of ∼2.4 nm, which estimates the size of the target for the diffusional encounter (a) (23). This target size corresponds to ∼6 bp, suggesting that when Pol β binds within ∼6 bp of a target it will locate it and catalyze insertion with an efficiency of 0.75 (Supplementary Figure S4). Because there is equal probability of searching upstream or downstream after leaving a product site, the total mean searching length of Pol β at 150 mM ionic strength is ∼24 bp. The DNA binding footprint of Pol β on 1-nt gap containing DNA is ∼7 bp (30). Thus, the mean search length of Pol β is not just a reflection of the DNA binding footprint.

Figure 5.

Site-spacing dependence of Fp normalized by the insertion efficiency (E). The Fp was measured for processive substrates containing 10, 20, 40 and 80 bp spacing distances (bottom x-axis) at 150 mM ionic strength. The top x-axis represents the distance (nm) between the two 1-nt gaps. The mean and standard deviation from three independent experiments is shown. The Fp is normalized by the efficiency of insertion (Supplementary Figure S4). The red line represents the best fit to a sliding mechanism (Equation 5). The blue line is a fit to a hopping mechanism (Equation 6).

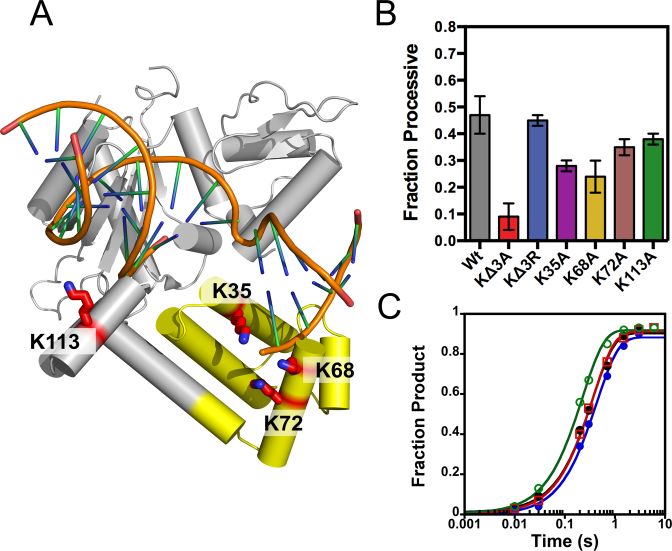

The positively charged 8-kDa lyase domain is used in processive searching

Figure 3A suggests that the molecular interactions that are made during the search process are electrostatic in nature, which presumably arise from positively charged regions in Pol β and the negatively charged phosphate backbone of DNA. We sought to identify the positive charged regions in Pol β that are involved in processive searching. An analysis of the electrostatic potential of Pol β reveals that the 8-kDa lyase domain is the most positively charged region, with a theoretical pI of ∼9.9 (31-kDa has a pI of ∼6.4). Mutation of three lysines (K35, K68 and K72A, termed KΔ3A) (Figure 6A) to alanine within the lyase domain of Pol β significantly decreases processivity, from 0.47 ± 0.07 to 0.09 ± 0.05 at 100 mM ionic strength, for Wt and KΔ3A, respectively (Figure 6B). Analysis of the individual mutants within the processive assay reveals that K35 and K68 are mainly responsible for the reduction in processivity seen with K3ΔA. Interestingly, mutation of K35, K68 and K72 to arginine (KΔ3R) has no effect on processivity, suggesting that non-specific positive charge within the lyase domain is responsible for processive searching. To determine the extent to which positive charge within the 31-kDa domain could contribute to processive searching, we mutated K113 to alanine (K113A). This mutant has little effect on processivity, suggesting that positive charge within the lyase domain is specific for searching. Importantly, all of the mutants examined have comparable kpol values, indicating that decreases in Fp are not due to reduced nucleotide insertion activity (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Pol β uses the positively charged 8-kDa lyase domain for processive searching. Crystal structure of Pol β bound to a 1-nt gapped DNA (PDB 3ISB). (A) The lysine residues mutated to alanine are shown as red sticks. Lysines 35, 68 and 72 reside in the lyase domain (yellow) and K113 within the 31-kDa domain (gray). (B) The fraction processive at 100 mM ionic strength was measured using the P20 substrate with each mutant Pol β under standard reaction conditions. The mean and standard deviation is shown for three independent experiments. (C) Single-turnover analysis for Pol β catalyzed nucleotide insertion measured with indicated mutant enzymes at 100 mM ionic strength. The Wt data is shown as black circles, KΔ3A as red squares, KΔ3R as blue circles, and K113A as green open circles. The nucleotide insertion rate constant (kpol) is comparable among the variant enzymes: Wt (2.8 ± 0.2 s−1), KΔ3A (2.3 ± 0.2 s−1), KΔ3R (2.8 ± 0.2 s−1) and K113A (4.4 ± 0.2 s−1).

To further understand the decrease in processivity with KΔ3A Pol β we measured the efficiency of nucleotide insertion with the pulse-chase partition assay as described for Wt Pol β in Supplementary Figure S4. The efficiency for KΔ3A Pol β is 0.52 ± 0.02 (Supplementary Figure S4D), representing a modest decrease as compared to Wt (0.75 ± 0.07). The kpol for KΔ3A is similar to Wt (Figure 6C), meaning koff is increased ∼2.3-fold as compared to Wt (Equation 3 and Supplementary Table S3).

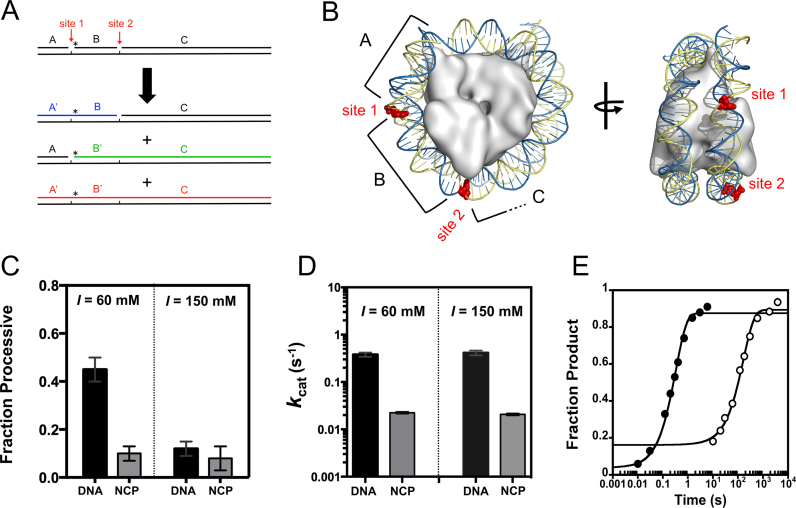

Pol β is not processive in nucleosomes because DNA synthesis is inhibited

The genomic landscape is significantly shaped by the presence of histone octamers, forming nucleosome core particles (NCPs). The extent to which Pol β searches and repairs DNA damage in NCPs is relatively unknown. To provide insight into this question, our processive assay design was applied to the mononuclesome 601 model system (Figure 7A). Using the NCP crystal structure as a guide, two 1-nt gaps were introduced within a region of the 601 DNA that has been shown to be relatively reactive (i.e. not the near the dyad) (Figure 7B) (25). No significant processivity was observed with the NCP substrate at 60 and 150 mM ionic strength, whereas free DNA showed processivity that was ionic strength dependent, as expected (Figure 7C). These data suggest that Pol β does not perform a productive processive search for gaps in well positioned NCPs.

Figure 7.

Pol β catalyzed nucleotide insertion is reduced in the 601 NCP resulting in a lack of processivity. (A) NCP processive substrate design. Schematic depicting positions of 1-nt gaps and labeling strategy. Oligonucleotide B is 5΄ labeled with a 32P phosphate. Site one is located 15 nts and site two 32 nts from the 5΄ end. Reactions were performed as described in Figure 2A. (B) Crystal structure of the NCP containing 601 sequence (PDB: 3LZ0). The positions of the 1-nt gaps are shown as red spheres. (C) Bar graphs representing the fraction of processive Pol β molecules in DNA and NCP reactions at 60 mM and 150 mM ionic strength. The Fp values at 60 mM ionic strength are 0.46 ± 0.05 and 0.1 ± 0.03 for DNA and NCP, respectively. The Fp values at 150 mM ionic strength are 0.12 ± 0.03 and 0.08 ± 0.05 for DNA and NCP, respectively. The error bars report the mean and standard deviation from at least two measurements performed with two independent NCP preparations. (D) Bar graph representing the kcat (for total product formation) for DNA and NCP at 60 and 150 mM ionic strength. The kcat values at 60 mM ionic strength are 0.38 ± 0.07 s−1 and 0.02 ± 0.002 s−1 for DNA and NCP, respectively. The kcat values at 150 mM ionic strength are 0.41 ± 0.09 s−1 and 0.02 ± 0.002 s−1 for DNA and NCP, respectively. The error bars report the mean and standard deviation from at least two measurements performed with two independent NCP preparations. (E) Single-turnover time-courses for Pol β catalyzed nucleotide insertion at site two. Reaction conditions include 2 μM Pol β with 50 nM DNA (closed) and NCP (open), 150 mM ionic strength, 50 μM dGTP, and standard reaction conditions. The non-zero y-intercept for the NCP time-course is proposed to be a result of the NCP preparation containing a fraction of free DNA or a population of NCP that reacts before the major phase. The data are fit to a single-exponential equation yielding kobs values of 3.0 ± 0.2 s−1 and 0.006 ± 0.001 s−1 for DNA and NCP, respectively.

The lack of processivity in NCPs can be attributed to changes in three variables: nucleotide insertion (kpol), searching (ksearch) and koff (Equation 2). During the processive measurements with the NCP substrate the Pol β enzyme concentration had to be increased 20-fold to observe product formation within a reasonable time-course, suggesting nucleotide insertion catalyzed by Pol β is significantly reduced at these sites in the NCP. Indeed, the kcat value was found to be ∼20-fold lower for the NCP substrate as compared to DNA (Figure 7D). To provide a further explanation for such a decrease in activity, single-turnover measurements were performed with the NCP substrate. These experiments revealed that the single-turnover rate constant for nucleotide insertion at site two in the NCP substrate is decreased 500-fold, as compared to DNA (Figure 7E). The rate constant for nucleotide insertion under single-turnover conditions is comparable to the rate constant measured under multiple-turnover conditions for the NCP substrate, suggesting that the rate constants are measuring the same step. This step must be at or before chemistry, and given its low value it likely reflects the rate constant governing the dynamic exposure of the DNA from the histone octamer (see discussion). Therefore, productive processive searching of Pol β within the 601 NCP does not occur because Pol β catalyzed DNA synthesis is strongly inhibited.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to determine if Pol β is capable of utilizing facilitated diffusion to locate its DNA substrates. An assay to monitor the DNA searching ability of Pol β was developed and revealed the surprising finding that Pol β uses facilitated diffusion for DNA damage site localization. Characterization of this search process has revealed three important mechanistic insights: the search process is ionic strength dependent, Pol β employs a hopping mechanism, and the positively charged lyase domain of Pol β is instrumental in searching.

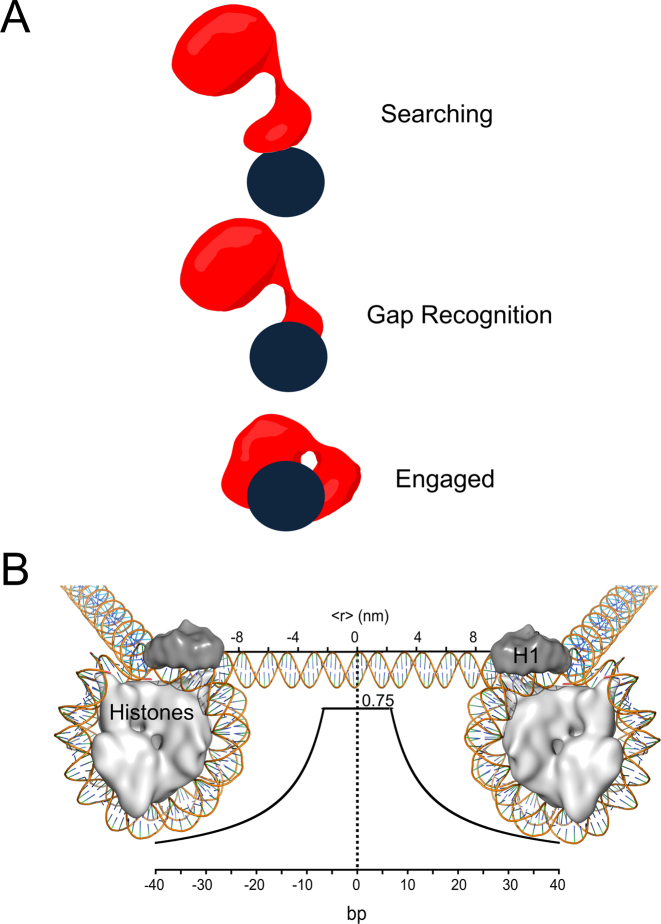

A proposed mechanism of damage search by Pol β is summarized in Figure 8A. In the searching mode, we propose Pol β uses positively charged lysine residues within its lyase domain to hop along DNA. Once a gap in DNA is encountered, the lyase domain makes specific interactions with the exposed nucleobases unique to gapped DNA. These additional interactions strengthen the affinity between the lyase domain and DNA allowing for the 31-kDa domain to engage. Thus, the lyase domain is used to search DNA and as such it is the first to recognize and engage damage.

Figure 8.

Models of Pol β searching and gap recognition. (A) Proposed modes of Pol β substrate search and recognition. The dark blue circle represents DNA and is positioned such that the viewpoint is looking down DNA. Pol β is shown as a red cartoon. In the searching mode, Pol β is proposed to mainly use its lyase domain to scan DNA in a hopping mechanism. Once a gap is encountered, the lyase domain makes specific interactions with gapped DNA, allowing for the 31-kDa domain to engage. (B) The probability of Pol β locating and catalyzing nucleotide insertion within a single DNA binding encounter near predicted physiological ionic strength. The curve represents the fit to the hopping equation shown in Figure 5. The y-axis represents the probability, or fraction processive (0-1), of Pol β successfully locating and catalyzing nucleotide insertion. The bottom x-axis represents the number of base pairs and the top axis is the corresponding distance (nm). An approximant DNA linker length of 56 bps is shown for reference. This model can be most easily interpreted by using the origin as the site of DNA damage (a 1-nt gap). A horizontal line ∼6 bp down and up-stream from the origin at a probability of 0.75 indicates that when Pol β binds within 6 bp of damage it has a 0.75 chance of catalyzing nucleotide insertion (Supplementary Figure S4). If Pol β binds ∼10 bp down or up-stream from a 1-nt gap it has ∼50% chance of locating and catalyzing nucleotide insertion. Of the Pol β molecules that are processive, 50% will travel a distance of ∼12 bp down or up-stream, resulting in a mean search footprint of ∼24 bp.

This work provides evidence that Pol β can employ a processive search for DNA damage, but does not rule out the other mechanisms of site location outlined in Figure 1A (3D diffusion and protein recruitment). For instance, not all molecules of Pol β are processive near predicted physiological ionic strengths, meaning in vivo a fraction of Pol β molecules are utilizing random 3D diffusion or are involved in protein-protein interactions important for recruitment. For optimal target site location, theoretical modeling suggests that a site-specific DNA binding protein must balance searching in local DNA, in a redundant search, with a global genome wide-search (13,31). This balance can be reached by a processive enzyme using intersegmental transfer and/or 3D diffusion coupled with protein recruitment models (31). One model of Pol β recruitment via protein-protein interactions involves a PARP1/XRCC1 complex (32,33). In this model, PARP1 binds to single-strand breaks, catalyzes PARylation of itself or other repair proteins, providing a binding site for XRCC1. Since XRCC1 is a binding partner of Pol β, recruitment of XRCC1 via PARP1 PARylation localizes Pol β to damage. The importance of this proposed recruitment mechanism for Pol β damage site localization may not be that significant since cells harbouring mutations in XRCC1 that disrupt Pol β binding display Wt-like resistance to H2O2 and MNNG (34). Thus recruitment via PARP1/XRCC1 is not required for Pol β damage site localization (35). It has also been hypothesized that APE1 may directly interact with Pol β (via a protein-protein interaction) to facilitate coordinated repair (36–38). However, strong evidence for a meaningful direct interaction between Pol β and APE1 is lacking and further studies are required to elucidate the proposed mechanism of handoff between these two enzymes.

Many proteins that have DNA associated functions use processive search mechanisms, these include transcription factors, endonucleases, and DNA glycosylases. Pol β exhibits comparable fraction processive values to many of these enzymes (Supplementary Figure S10). Interestingly, the BER DNA glycosylases UNG, OGG1 and AAG and the BER endonuclease, APE1, also employ processive search mechanisms, suggesting that this may be a common strategy employed within the BER pathway (21,22,39). The mean search lengths of these processive enzymes have not been determined or were determined at low ionic strengths confounding direct comparisons to Pol β (22). Single-molecule studies performed with DNA glycosylases suggest longer searching lengths (hundreds of base pairs) than the lengths measured by processive biochemical assays (28,40,41). In processive biochemical assays every active molecule of the enzyme in solution is considered. In contrast, single-molecule experiments are more likely to observe proteins that have long binding-lifetimes on DNA due to temporal and spatial limitations of current setups (42). Thus, longer scanning lengths observed in single-molecule experiments could be rare events (28), representing the behavior of only a small fraction of the total protein in solution.

Application of the processive assay with the 601 NCP model system revealed that Pol β is not processive in these NCPs because nucleotide insertion activity is significantly reduced. Since the readout for processivity is product formation, we cannot directly determine if Pol β hops on DNA bound to histones or at least transverse NCPs to get to linker regions. However, it would seem futile to spend time searching NCPs for DNA damage because once damage is encountered Pol β is more likely to dissociate from it than catalyze nucleotide insertion. The rate-limiting step for Pol β catalysis within the NCP likely reflects the dissociation of DNA from the histone-DNA complex. The region of DNA 18–37 bp from the entry/exit site has an estimated koff rate constant of 0.012 s−1, which is comparable to the kcat value for nucleotide insertion (0.01 s−1) catalyzed by Pol β for both sites (located 15 and 32 bp from the entry/exit site) (43). The unwrapping of the DNA from the histones being the rate limiting step for Pol β catalysis is consistent with previous studies in which the activity of Pol β near the DNA entry/exit sites is greater than near the dyad (25). Similarly, the lack of a strong dependence on the helical orientation of the gap (in vs out) on Pol β DNA synthesis is consistent with the model of Pol β requiring interactions with both DNA strands (25).

Depending on the helical orientation with respect to the histone core, DNA glycosylases can remove damaged bases positioned in NCPs with similar efficiency as with DNA (44,45). Similarly, APE1 can perform backbone hydrolysis within certain regions (44). In contrast, as shown here and in previous studies, the activity of Pol β is inhibited in NCPs (25,44,46,47). Here, we quantify this inhibition to be at least two-orders of magnitude slower for single-turnover nucleotide insertion in NCPs as compared to free DNA. It's interesting that the first two steps of BER can occur in NCPs, because these steps produce reactive intermediates (abasic sites and dRPs, respectively), of which the dRP may not be repaired by the downstream enzyme (Pol β). However, the lack of Pol β DNA synthesis activity does not necessarily imply that lyase activity is inhibited within the context of an NCP, especially considering that the 8-kDa domain is required for this activity and may not need to fully engage both DNA strands. Further studies will be required to examine this question.

Given the ∼500-fold decrease in nucleotide insertion catalyzed by Pol β within the 601 NCP, as compared to free DNA, we propose that the repair footprint of Pol β mainly resides within accessible regions of the genome, such as linker regions between NCPs. The mean search footprint of Pol β near physiological ionic strength is ∼24 bp. Linker regions vary from 0 to 100 bp (48), thus a mean search length of ∼24 bp may be optimized to scan the relatively short linker regions of the genome (Figure 8B).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the members of the Wilson lab for comments. In particular, we thank David Shock and William Beard for advice on designing Pol β kinetic assays and the method for active fraction determination.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Z01ES050158 and Z01ES050159]. Funding for open access charge: Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Z01ES050158 and Z01ES050159].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Krokan H.E., Bjoras M.. Base excision repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013; 5:a012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wilson D.M. 3rd, Barsky D.. The major human abasic endonuclease: formation, consequences and repair of abasic lesions in DNA. Mutat. Res. 2001; 485:283–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matsumoto Y., Kim K.. Excision of deoxyribose phosphate residues by DNA polymerase beta during DNA repair. Science. 1995; 269:699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sobol R.W., Horton J.K., Kuhn R., Gu H., Singhal R.K., Prasad R., Rajewsky K., Wilson S.H.. Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase-beta in base-excision repair. Nature. 1996; 379:183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumar A., Abbotts J., Karawya E.M., Wilson S.H.. Identification and properties of the catalytic domain of mammalian DNA polymerase beta. Biochemistry. 1990; 29:7156–7159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar A., Widen S.G., Williams K.R., Kedar P., Karpel R.L., Wilson S.H.. Studies of the domain structure of mammalian DNA polymerase beta. Identification of a discrete template binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1990; 265:2124–2131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dianov G., Price A., Lindahl T.. Generation of single-nucleotide repair patches following excision of uracil residues from DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992; 12:1605–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prasad R., Shock D.D., Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. Substrate channeling in mammalian base excision repair pathways: passing the baton. J. Biol. Chem. 2010; 285:40479–40488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilson S.H., Kunkel T.A.. Passing the baton in base excision repair. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000; 7:176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fu D., Calvo J.A., Samson L.D.. Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012; 12:104–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berg O.G., von Hippel P.H.. Diffusion-controlled macromolecular interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1985; 14:131–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berg O.G., Winter R.B., von Hippel P.H.. Diffusion-driven mechanisms of protein translocation on nucleic acids. 1. Models and theory. Biochemistry. 1981; 20:6929–6948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halford S.E., Marko J.F.. How do site-specific DNA-binding proteins find their targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32:3040–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kad N.M., Van Houten B.. Dynamics of lesion processing by bacterial nucleotide excision repair proteins. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2012; 110:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hedglin M., Zhang Y., O’Brien P.J.. Isolating contributions from intersegmental transfer to DNA searching by alkyladenine DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2013; 288:24550–24559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hedglin M., O’Brien P.J.. Hopping enables a DNA repair glycosylase to search both strands and bypass a bound protein. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010; 5:427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. Purification and domain-mapping of mammalian DNA polymerase beta. Methods Enzymol. 1995; 262:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patterson T.A., Little W., Cheng X., Widen S.G., Kumar A., Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. Molecular cloning and high-level expression of human polymerase beta cDNA and comparison of the purified recombinant human and rat enzymes. Protein Expr. Purif. 2000; 18:100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beard W.A., Shock D.D., Batra V.K., Prasad R., Wilson S.H.. Substrate-induced DNA polymerase beta activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014; 289:31411–31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beard W.A., Shock D.D., Wilson S.H.. Influence of DNA structure on DNA polymerase beta active site function: extension of mutagenic DNA intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 2004; 279:31921–31929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hedglin M., O’Brien P.J.. Human alkyladenine DNA glycosylase employs a processive search for DNA damage. Biochemistry. 2008; 47:11434–11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Porecha R.H., Stivers J.T.. Uracil DNA glycosylase uses DNA hopping and short-range sliding to trap extrahelical uracils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105:10791–10796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stanford N.P., Szczelkun M.D., Marko J.F., Halford S.E.. One- and three-dimensional pathways for proteins to reach specific DNA sites. EMBO J. 2000; 19:6546–6557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berg H.C. Random Walks in Biology. 1993; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodriguez Y., Smerdon M.J.. The structural location of DNA lesions in nucleosome core particles determines accessibility by base excision repair enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2013; 288:13863–13875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Terry B.J., Jack W.E., Modrich P.. Facilitated diffusion during catalysis by EcoRI endonuclease. Nonspecific interactions in EcoRI catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1985; 260:13130–13137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vande Berg B.J., Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. DNA structure and aspartate 276 influence nucleotide binding to human DNA polymerase beta. Implication for the identity of the rate-limiting conformational change. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276:3408–3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rowland M.M., Schonhoft J.D., McKibbin P.L., David S.S., Stivers J.T.. Microscopic mechanism of DNA damage searching by hOGG1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:9295–9303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gowers D.M., Wilson G.G., Halford S.E.. Measurement of the contributions of 1D and 3D pathways to the translocation of a protein along DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005; 102:15883–15888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moon A.F., Gosavi R.A., Kunkel T.A., Pedersen L.C., Bebenek K.. Creative template-dependent synthesis by human polymerase mu. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:E4530–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Slutsky M., Mirny L.A.. Kinetics of protein-DNA interaction: facilitated target location in sequence-dependent potential. Biophys. J. 2004; 87:4021–4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. El-Khamisy S.F., Masutani M., Suzuki H., Caldecott K.W.. A requirement for PARP-1 for the assembly or stability of XRCC1 nuclear foci at sites of oxidative DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003; 31:5526–5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lan L., Nakajima S., Oohata Y., Takao M., Okano S., Masutani M., Wilson S.H., Yasui A.. In situ analysis of repair processes for oxidative DNA damage in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101:13738–13743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fang Q., Inanc B., Schamus S., Wang X.H., Wei L., Brown A.R., Svilar D., Sugrue K.F., Goellner E.M., Zeng X. et al. HSP90 regulates DNA repair via the interaction between XRCC1 and DNA polymerase beta. Nat. Commun. 2014; 5:5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Horton J.K., Gassman N.R., Dunigan B.D., Stefanick D.F., Wilson S.H.. DNA polymerase beta-dependent cell survival independent of XRCC1 expression. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2015; 26:23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bennett R.A., Wilson D.M. 3rd, Wong D., Demple B.. Interaction of human apurinic endonuclease and DNA polymerase beta in the base excision repair pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997; 94:7166–7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mol C.D., Izumi T., Mitra S., Tainer J.A.. DNA-bound structures and mutants reveal abasic DNA binding by APE1 and DNA repair coordination [corrected]. Nature. 2000; 403:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moor N.A., Vasil’eva I.A., Anarbaev R.O., Antson A.A., Lavrik O.I.. Quantitative characterization of protein-protein complexes involved in base excision DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:6009–6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carey D.C., Strauss P.R.. Human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease is processive. Biochemistry. 1999; 38:16553–16560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nelson S.R., Dunn A.R., Kathe S.D., Warshaw D.M., Wallace S.S.. Two glycosylase families diffusively scan DNA using a wedge residue to probe for and identify oxidatively damaged bases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:E2091–E2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blainey P.C., van Oijen A.M., Banerjee A., Verdine G.L., Xie X.S.. A base-excision DNA-repair protein finds intrahelical lesion bases by fast sliding in contact with DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103:5752–5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Redding S., Greene E.C.. How do proteins locate specific targets in DNA. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013; 570, doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tims H.S., Gurunathan K., Levitus M., Widom J.. Dynamics of nucleosome invasion by DNA binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2011; 411:430–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Beard B.C., Wilson S.H., Smerdon M.J.. Suppressed catalytic activity of base excision repair enzymes on rotationally positioned uracil in nucleosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003; 100:7465–7470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ye Y., Stahley M.R., Xu J., Friedman J.I., Sun Y., McKnight J.N., Gray J.J., Bowman G.D., Stivers J.T.. Enzymatic excision of uracil residues in nucleosomes depends on the local DNA structure and dynamics. Biochemistry. 2012; 51:6028–6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Menoni H., Gasparutto D., Hamiche A., Cadet J., Dimitrov S., Bouvet P., Angelov D.. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling is required for base excision repair in conventional but not in variant H2A.Bbd nucleosomes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007; 27:5949–5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Odell I.D., Barbour J.E., Murphy D.L., Della-Maria J.A., Sweasy J.B., Tomkinson A.E., Wallace S.S., Pederson D.S.. Nucleosome disruption by DNA ligase III-XRCC1 promotes efficient base excision repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011; 31:4623–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Valouev A., Johnson S.M., Boyd S.D., Smith C.L., Fire A.Z., Sidow A.. Determinants of nucleosome organization in primary human cells. Nature. 2011; 474:516–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.