Abstract

Background: Some women who use cyclic hormonal contraception (CHC) suffer from premenstrual symptoms; whether their symptoms differ from women who do not use CHC is not clear.

Objective: To compare women who use or do not use CHC on perimenstrual symptom timing and change severity.

Study Design: We analyzed daily symptom ratings from women who requested participation in (Screened Cohort: 103 used CHC and 387 did not) or were randomized in (Randomized Cohort: 41 used CHC and 211 did not) a clinical trial for premenstrual syndrome. We used effect sizes to compute and compare change scores between cycle phases in four partially overlapping perimenstrual windows defined relative to day 1 of menses [(−6, −1), (−5, 1), (−4, 2), (−3, 3)]. Differences in magnitude of change and timing were estimated using linear mixed-effects models.

Results: Both cohorts showed a significant two-way interaction between CHC use and symptom change scores (p < 0.01) and a significant main effect of perimenstrual window (p < 0.0001). Overall menstrual cycle symptom change was greater for the nonhormonal contraception versus hormonal contraception group. In the Screened Cohort, change scores were greater in the nonhormonal group specifically for depression (p = 0.04); anger or irritability (p < 0.01); and physical symptoms (p < 0.01). Mean change scores increased as the window shifted forward toward menses for both cohorts with the largest effect size and greatest group difference for (−4, 2) interval.

Conclusions: CHC slightly attenuates menstrual cycle symptom change. The (−4, 2) perimenstrual interval shows the largest change compared with postmenses.

Keywords: : contraception, menstrual cycle, mental health

Introduction

Moderate to severe premenstrual syndrome (PMS), including premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), is characterized by affective, behavioral, and physical symptoms that begin within a few weeks of the onset of menses and remit shortly after menses. Symptoms identified by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for PMS1 and by the American Psychiatric Association for PMDD2 reflect the most common and problematic symptoms identified in clinical and epidemiological research.3–5 Clinical trials that employed hormonal interventions find that some are effective,6–8 while others are not.9–11 Regardless of overall efficacy, these trials show that a subset of participants are symptomatic both before and after exogenous hormone exposure rather than simply because of hormone exposure. Despite this, some experts consider symptomatic women who use cyclic hormonal contraception (CHC) as suffering from a hormonally induced mood disorder rather than PMS or PMDD.12 Criteria set forth in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5 (DSM 5) for PMDD stipulated that symptoms must be present in the final week before the onset of menses,2 but the earlier version stated that symptoms must be present during the last week of the luteal phase,13 inferring that only women with an intact menstrual cycle are eligible for the diagnosis.

A small literature, conducted in mildly symptomatic women, compares the timing and severity of premenstrual symptom expression in women who are or are not using CHC.14–22 Studies varied on whether CHC use influences the timing of peak symptom expression.19,21,22 A relatively consistent finding is the association between attenuated symptom severity in women who take monophasic hormonal contraceptive pills compared with women who do not use hormonal contraception, although even here studies are not uniform.14–16,18,22

Both a change in symptom pattern and severity can influence whether a woman meets criteria for PMS or PMDD. Given the possible influence of exogenous hormones on symptom expression, we sought to compare the relative severity and timing of premenstrual symptom expression in women who do or do not use CHC and endorse moderate to severe symptoms. We used data from women who expressed interest in participating in a PMS clinical trial (Screened Cohort) and compared the degree and timing of menstrual cycle symptom change in users and nonusers of CHC. We repeated these comparisons in the subset who were randomized into the clinical trial (Randomized Cohort). Based upon the literature, we hypothesized that women who use CHC would have less severe symptom changes across the menstrual cycle. Our second hypothesis was that the timing of symptom onset relative to onset of menses would be similar in the two groups. A minimal or lack of difference in these parameters would mean that women who use CHC may be appropriately diagnosed with having PMS and benefit from currently approved treatments if they otherwise meet diagnostic criteria.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment and screening

Subjects in the Screened Cohort included women who sought participation in a National Institute of Mental Health-funded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of sertraline for treatment of PMS.23 The Randomized Cohort included the subset who participated in the trial. The parent study was conducted in New Haven, Connecticut, New York City, New York, and Richmond, Virginia. The majority of participants were recruited not only via direct mail but also via advertisements in local media, internet sites, and posters and brochures placed in the community and academic centers. Respondents interested in participation were called for a brief prescreening interview during which we obtained verbal consent and described study procedures. Potentially eligible respondents who did not meet exclusionary criteria and retrospectively endorse moderate to severe PMS, according to DSM 5 PMDD criteria, were invited to participate in a face-to-face screening office visit. Users of CHC included women who took a variety of monophasic and triphasic oral contraceptives, with 4–7 days of inert pills every 28 days, and women who used a vaginal ring hormonal contraceptive 3 weeks per month. To be considered for participation, they were required to have used this method for at least 6 months. All respondents were given at least 8 daily rating forms (each form tracks 1 week of symptoms) to return weekly. Study staff collected and reviewed daily ratings. To participate in the trial, respondents were required to meet specific criteria for a diagnosis of having PMDD (see below) for at least two of three menstrual cycles. The daily rating criteria required for participation were not shared with respondents. Women were reimbursed $50 for completion of daily ratings. Those who did not meet screening criteria were given treatment referrals if they were desired.

Study procedures

Women were eligible for screening if they were aged between 18 and 48 years; had menstrual cycles of 21–35 days; and could speak and write in English. Women were ineligible for screening if they used contraceptives with drospirenone, an FDA-approved treatment for PMS; had suffered from a major depressive episode or eating disorder in the past year or a psychotic disorder during their lifetime; were receiving pharmacotherapy for a psychiatric disorder; used recreational drugs at least once per week; had severe suicidal thoughts; had a history of hypersensitivity to the study compound, sertraline; were pregnant or lactating; were planning on relocating during the study period; or were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent. Women who confirmed symptom criteria for PMS and acquiesced to participate in the randomized, double-blind, parallel clinical trial were allocated to either sertraline or similar appearing placebo for six menstrual cycles. Procedures and results of the trial have been presented elsewhere.23 The study was approved by human subjects' boards at the collaborating institutions.

Study measures

We used the Daily Rating of Severity of Problems (DRSP) to catalog daily symptoms during the screening cycles. The DRSP comprised 21 items that reflect the 11 candidate symptoms for PMDD according to DSM IV13 and DSM 5.2 Some candidate symptoms are broken into several individual items. For example, the first DSM IV symptoms are markedly depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts. The DRSP queries each of these components individually, although positive endorsement of only one of these components is sufficient to meet the DSM IV criterion. Symptoms included (1) depressed, hopeless, or guilty; (2) anxious or tense; (3) mood swings or sensitivity to rejection; (4) anger or irritability; (5) diminished interest; (6) difficulty concentrating; (7) lethargy; (8) increased appetite or cravings; (9) increased or decreased sleep; (10) felt overwhelmed or out of control; and (11) breast discomfort, headache, or muscle pain. The DRSP rating scale symptoms are scored as follows: 1 = not at all, 2 = minimal, 3 = mild, 4 = symptoms, 5 = severe, and 6 = extreme. In addition to the symptoms, the DRSP includes three items that are to be used to rate functional impairment.

To assess the magnitude of symptom fluctuations across the menstrual cycle, we created change scores that described the difference between the typically asymptomatic postmenstrual interval and a symptomatic perimenstrual interval. Based upon previous work,23,24 we selected days 7–12 after menses (follicular phase for ovulating participants) for the asymptomatic interval and four partially overlapping 6-day symptomatic perimenstrual windows defined relative to the first day of menses: (−6, −1), (−5, 1), (−4, 2), and (−3, 3). Three of the four perimenstrual windows included the first few days of menses because we,24 and others,14–21,22 find that peak symptom expression is not only restricted to the days before onset of menses but also includes the first few days of menses. Additionally, if the use of CHC shifted the symptomatic period to the time of menstrual flow (e.g., day 1, 2, or 3 of the menstrual cycle), we did not want to miss an effect. We employed the effect size method as described by Schnurr,25 which measures the change between postmenstrual to perimenstrual intervals, after accounting for the background variability across the menstrual cycle. The change score was calculated as the difference between the average symptom score rating in the perimenstrual window and the previous postmenstrual phase divided by the standard deviation of the entire cycle's ratings.

Statistical approach

We used two cohorts for our analyses. The first included all women who requested participation in the clinical trial, had known CHC use status, and kept at least one complete menstrual cycle of daily ratings. We included an analysis of this Screened Cohort because CHC-associated changes could have influenced a participant's ability to meet criteria for PMDD if, for example, the symptomatic window was limited to the menstrual rather than premenstrual phase. The Randomized Cohort included two qualifying screening cycles for all women who were randomized into the clinical trial and hence met DSM IV symptom criteria for PMDD.

We compared characteristics for women who were using CHC with those not using CHC (non-CHC) for each cohort using Student's t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. We used Fisher's exact test for comparisons that included expected cell sizes that were less than five.

Separate analyses were conducted for the Screened and Randomized Cohorts. We used linear mixed-effects models to assess differences in change scores among perimenstrual windows by CHC group and symptom. The within-subject effects in the models were symptom type and perimenstrual phase window [(−6, −1), (−5, 1), (−4, 2), (−3, 3)], the between-subject factor was CHC use (yes or no). All two- and three-way interactions were included in the models. We used a random effect for subject and cycle within subject. An α level of 0.05 was used for all main effect and interaction tests. We also performed exploratory mixed model analyses by symptom group with unstructured variance–covariance matrix of the errors over the four intervals for each symptom group. We compared least square means (LSMs) to study significant effects in the models. Given the exploratory nature of the analysis, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. We used SAS, version 9.4, to fit all models.

Results

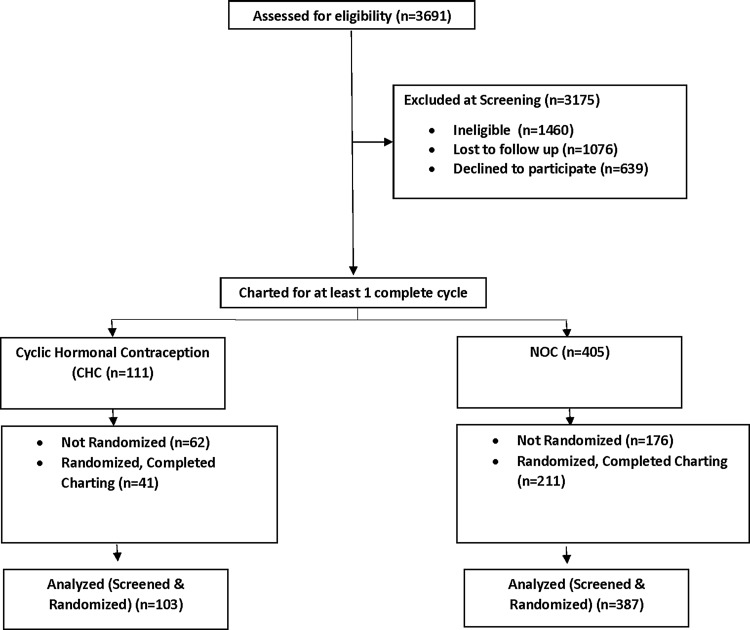

The analysis of the Screened Cohort included 490 women (103 CHC and 387 non-CHC) and 1002 menstrual cycles (212 CHC and 790 non-CHC). The analysis of the Randomized Cohort included 252 women (41 CHC and 211 non-CHC) and 537 menstrual cycles (88 CHC and 449 non-CHC) (see Figure 1). Participant Characteristics are shown in Table 1. For the Screened Cohort, the non-CHC compared with the CHC women were slightly older (35.2 ± 6.6 vs. 30.1 ± 7.2, p < 0.001), more likely to be black (18.6% vs. 7.8%, p = 0.013), and had a higher rate of marriage (38.8% vs. 20.4%, p < 0.001). Mean age (35.0 ± 6.7 vs. 30.0 ± 6.0, p < 0.001) and the rate of marriage (40.3% vs. 19.5%, p = 0.19) were also higher in the non-CHC women from the Randomized Cohort. Mean cycle length was about 1 day longer in the non-CHC group compared with the CHC group (29.0 8.2 ± vs. 27.9 ± 3.9, p = 0.049) in the Randomized Cohort.

FIG. 1.

Screening and randomized groups.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| All screened | Randomized | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | CHC | Non-CHC | p-Value | CHC | Non-CHC | p-Value |

| Age (mean, years) | 30.1 | 35.2 | <0.001a | 30.0 | 35.0 | <0.001a |

| Race [n (%)] | ||||||

| White | 80 (77.7) | 284 (73.4) | 0.45b | 33 (80.6) | 164 (77.7) | 0.85b |

| Black | 8 (7.8) | 72 (18.6) | 0.01b | 3 (7.3) | 36 (17.1) | 0.18b |

| Native American | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 0.51c | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.30c |

| Asian | 2 (1.9) | 4 (1.0) | 0.61c | 1 (2.4) | 2 (0.9) | 0.41c |

| Other | 9 (8.7) | 24 (6.2) | 0.49b | 3 (7.3) | 8 (3.8) | 0.39c |

| Unknown | 3 (2.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0.03c | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Ethnicity [n (%)] | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 75 (72.8) | 248 (64.1) | 0.12b | 31 (75.6) | 144 (68.2) | 0.45b |

| Black (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) | 8 (7.8) | 72 (18.6) | 0.01b | 3 (7.3) | 36 (17.1) | 0.18b |

| Hispanic (any race other than black) | 14 (13.6) | 52 (13.4) | 1.00b | 4 (9.8) | 24 (11.4) | 1.00c |

| Non-Hispanic (any race other than white or black) | 6 (5.8) | 15 (3.9) | 0.41c | 3 (7.3) | 7 (3.3) | 0.21c |

| Marital status [n (%)] | ||||||

| Married | 21 (20.4) | 150 (38.8) | <0.001b | 8 (19.5) | 85 (40.3) | 0.02b |

| Living with partner (not married) | 28 (27.2) | 47 (12.1) | <0.001b | 10 (24.4) | 24 (11.4) | 0.05b |

| Separated | 1 (1.0) | 9 (2.3) | 0.70c | 1 (2.4) | 4 (1.9) | 0.59c |

| Divorced | 5 (4.8) | 35 (9.0) | 0.24b | 3 (7.3) | 17 (8.0) | 1.00c |

| Single (never married) | 48 (46.6) | 146 (37.8) | 0.13b | 19 (46.4) | 81 (38.4) | 0.44b |

| Mean cycle length (days) | 27.8 | 28.3 | 0.25a | 27.9 | 29.0 | 0.05a |

| No. of cycles charted | ||||||

| 1 | 23 (22.3) | 89 (23.0) | 0.99b | 6 (14.6) | 40 (19.0) | 0.66b |

| 2 | 56 (54.4) | 203 (52.5) | 0.81b | 26 (63.4) | 113 (53.6) | 0.32b |

| >2 | 24 (23.3) | 95 (24.5) | 0.89b | 9 (22.0) | 58 (27.4) | 0.59b |

The following statistical tests were used to estimate differences between groups: at-test; bchi-square test; cFisher's exact test.

CHC, cyclic hormonal contraception.

The results of the linear mixed-effects models indicated nonsignificant three-way interactions between group, perimenstrual window, and symptom type [Screened Cohort: F(30, 27000) = 0.35, p > 0.99, Randomized Cohort: F(30, 14000) = 0.20, p > 0.99]. The LSMs and standard errors by group, perimenstrual window, and symptom type for each of the two cohorts are shown in Appendix Tables A1 and A2.

The two-way interaction between CHC use and symptom type was significant for both the Screened Cohort [F(10, 27000) = 3.12, p < 0.001] and the Randomized Cohort [F(10, 14000) = 3.40, p < 0.001]. Tables 2 and 3 show the LSMs by CHC group and symptom type for the Screened and Randomized Cohorts, respectively. In the Screened Cohort, the magnitude of change in symptoms was greater for the non-CHC group than for the CHC group, but significant differences for individual symptoms occurred only for depressed, hopeless, or guilty (p = 0.03); anger or irritability (p = 0.002); diminished interest (p = 0.001); difficulty concentrating (p = 0.03), feeling overwhelmed (p = 0.05), and physical symptoms (p = 0.04). In the Randomized Cohort, there were no significant differences in the magnitude of change between CHC groups for any individual symptoms.

Table 2.

Least Square Mean Effect Size for Cyclic Hormonal Contraception Groups by Symptom Subgroup for Screened Cohort

| Non-CHC | CHC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM ± SE | LSM ± SE | ||||

| n = 387 | n = 103 | Difference in effect size | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Depressed, hopeless, guilty | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.01, 0.29 | 0.03 |

| Anxious, tense | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.1, 0.27 | 0.08 |

| Mood swings or sensitivity to rejection | 0.94 ± 0.03 | 0.833 ± 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.02, 0.26 | 0.10 |

| Anger or irritability | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.08, 0.36 | 0.002 |

| Diminished interest | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.09, 0.37 | 0.001 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 0.79 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.01, 0.29 | 0.03 |

| Lethargy | 0.94 ± 0.03 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.06, 0.22 | 0.26 |

| Increased appetite or cravings | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.11 | −0.03, 0.25 | 0.13 |

| Increased or decreased sleep | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.07, 0.21 | 0.35 |

| Felt overwhelmed or out of control | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.00, 0.28 | 0.05 |

| Breast discomfort, headache, or muscle pain | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.01, 0.29 | 0.04 |

LSM, least square mean.

Table 3.

Least Square Mean Effect Size for Cyclic Hormonal Contraception Groups by Symptom Subgroup for Randomized Cohort

| Non-CHC | CHC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSM ± SE | LSM ± SE | Difference in effect size | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Depressed, hopeless, guilty | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.18, 0.19 | 0.96 |

| Anxious, tense | 1.26 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.16, 0.21 | 0.77 |

| Mood swings or sensitivity to rejection | 1.29 ± 0.04 | 1.45 ± 0.09 | −0.16 | −0.34, 0.02 | 0.09 |

| Anger or irritability | 1.27 ± 0.04 | 1.26 ± 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.18, 0.19 | 0.96 |

| Diminished interest | 1.24 ± 0.04 | 1.18 ± 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.12, 0.24 | 0.52 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 1.13 ± 0.04 | 1.25 ± 0.09 | −0.12 | −0.30, 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Lethargy | 1.26 ± 0.04 | 1.39 ± 0.09 | −0.13 | −0.31, 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Increased appetite or cravings | 1.15 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | −0.08 | −0.26, 0.11 | 0.41 |

| Increased or decreased sleep | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 1.11 ± 0.09 | −0.15 | −0.33, 0.04 | 0.12 |

| Felt overwhelmed or out of control | 0.99 ± 0.04 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.17, 0.19 | 0.90 |

| Breast discomfort, headache, or muscle pain | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 1.14 ± 0.09 | −0.02 | −0.21, 0.16 | 0.80 |

For the Screened Cohort, the linear mixed model also indicated significant main effects of symptom type [F(10, 27000) = 58.39, p < 0.0001], CHC use [F(1, 468) = 4.54, p = 0.03], and perimenstrual phase window [F(3, 27000) = 23.59, p < 0.001]. The LSMs indicated a slight increase in mean change score as the window shifted forward toward and beyond onset of menses [(−6, −1): LSM (SE) 0.70 (0.03); (−5, 1): LSM (SE) = 0.74 (0.03); (−4, 2): LSM (SE) = 0.79 (0.03); (−3, 3): LSM (SE) = 0.79 (0.03)]. All pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences between mean change scores (all p-values <0.006) with the exception of the difference in change score between the last two windows (−4, 2) and (−3, 3) (p = 0.99).

For the Randomized cohort, the linear mixed model indicated significant main effects for symptom type [F(10, 14000) = 40.87, p < 0.0001] and perimenstrual phase window [F(3, 14000) = 12.98, p < 0.0001]. Again, LSMs indicated slight increases in mean change score as the window moved forward, with the maximum score occurring in the interval (−4, 2); [(−6, −1): LSM (SE) = 1.10 (0.04); (−5, 1): LSM (SE) = 1.17 (0.04); (−4, 2): LSM (SE) = 1.22 (0.04); (−3, 3): LSM (SE) = 1.19 (0.04)]. Pairwise comparisons indicated that the interval (−6, −1) had a statistically significantly lower mean change score than the remaining three intervals (all p < 0.002). No other comparisons demonstrated statistically significant differences.

Exploratory separate analyses of the Screened cohort by symptom type largely confirmed the statistically significant differences among the windows. In particular, the (−6, −1) interval had significantly lower effect size than the rest of the intervals, the (−5, 1) interval had significantly lower effect size for 8 of 11 symptoms compared with the (−4, 2) interval and for two symptoms compared with the (−3, 3) interval, thus indicating the (−4, 2) interval as the one associated with the highest change score. Analyses also confirmed the findings of statistically significant differences between the CHC and no-CHC groups for depressed, hopeless, or guilty (p = 0.02); anger or irritability (p = 0.003); and physical symptoms (p = 0.01), but showed only a trend-level difference for decreased interest (p = 0.07) and no difference for difficulty concentrating (p = 0.18). Additionally, analyses indicated statistically significant interactions between group and interval for anxious–tense (p = 0.02), anger/irritability (p = 0.03), feeling overwhelmed (p = 0.02), and physical symptoms (0.007). Between-group differences were most pronounced for intervals (−5, 1) and (−4, 2) for anxious–tense (p = 0.02), (−6, −1), (−5, 1), and (−4, 2) for anger/irritability (p < 0.01), for intervals (−6, −1) and (−5, 1) on feeling overwhelmed (p = 0.04), and for (−4, 2) on physical symptoms (p = 0.005).

Exploratory analyses of the Randomized Cohort confirmed the results from the main analysis of differences among intervals on all symptoms (except lethargy and sleep, for which the mixed models did not converge) and no significant differences between the non-CHC and CHC groups. There were also no significant interactions between group and interval.

Discussion

As hypothesized, our analyses showed differences between treatment-seeking women who did or did not use CHC in the overall severity of menstrual cycle symptom change scores, although differences were small. For all screened, women using CHC showed significantly smaller perimenstrual change scores, particularly for depression; anger or irritability; and physical symptoms, than women not using CHC. Smaller overall symptom change scores were also found for the non-CHC versus CHC group in the Randomized Cohort, although pairwise analyses did not reveal significant differences for any particular symptoms. Regardless of CHC use, the magnitude of the change scores was influenced by the perimenstrual window. As the window moved forward to include menstrual days, change scores increased. The least symptomatic window in both cohorts was the one that occurred entirely during the premenstrual phase, between 1 and 6 days before the onset of menses. Not surprisingly, respondents who participated in the trial had larger change scores than the Screened cohort, many of whom did not meet symptom severity criteria for randomization.

Previous work that assessed the influence of CHC use on perimenstrual symptom expression was conducted with generally healthy women rather than women with moderate to severe premenstrual complaints. Still, the attenuation of cyclic changes found in women using CHC we found concur with several earlier studies.14–16,18,22 Additionally, Abraham14 found that the type of CHC did not matter, in that women who used either monophasic or triphasic hormonal contraceptive pills reported less difficulty with premenstrual symptoms than women who did not use hormonal contraceptive pills. On the other hand, Walker and Bancroft22 found that women who used triphasic hormonal contraceptive pills were more similar to nonusers in symptom changes than were women who used monophasic hormonal contraceptive pills. The few studies that failed to find blunting of symptom expression among CHC users may have had limited power to find group differences because they were generally small.17,20,21 No study included as large a cohort as the current study; study size as well as the focus on women who self-reported moderate to severe premenstrual problems likely enhanced our ability to find group differences.

Walker and Bancroft22 note that women who used CHCs tended to have a noncyclic pattern of symptoms. This may be true among our Screening Cohort as well since effect sizes were smaller in this group than the Randomized Cohort. Furthermore, only 40% of women who used CHC, but 55% of non-CHC users, met diagnostic criteria for PMDD and were included in our randomized clinical trial.23 We reported previously that there was no difference in response among participants who did versus did not use CHC,23 so it may be that while CHC users have milder premenstrual changes, once severe changes exist, they respond to the same treatments that help non-CHC users.

We previously found that the most symptomatic window for women who self-report PMS occurs in the 4 days before to the 2 days after onset of menses interval.24 The current analyses extend this finding to show that the symptomatic window is the same for women who do or do not take CHCs, whether or not they met criteria for PMDD. Of the three investigations we identified that explored a possible shift in timing of symptom expression, one was too small (n = 22) to show anything but very large differences,21 while the other two divided CHC users into those who took monophasic versus triphasic hormonal contraceptive pills.19,26 In both studies, monophasic pills were associated with a slight shift toward symptom expression in the menstrual versus premenstrual phase, although Ross et al.19 found earlier peak symptoms occurred in women who took triphasic pills. Our failure to find differences may reflect an averaging of effects for several types of hormonal contraception that future studies can explore.

Some limitations in our study bear mentioning. First, this was a secondary analysis and the study was not planned to address potential differences between CHC and non-CHC women in terms of their differences in perimenstrual symptom expression. In particular, while we were able to detect group differences (CHC users versus women with natural cycles) in symptom change as well as some two-way interactions, interactions showing group differences in symptom change by window likely require a larger cohort. Second, we only included four perimenstrual intervals and we may have missed an interval that differs between CHC groups. However, we included the perimenstrual intervals that in the past, and with other cohorts, have shown the greatest change.4 Third, there may be differences among the various CHC types and our cohort did not have the sample size, nor do our data have the granularity to assess this. Finally, there were demographic differences that may have been meaningful. Older women were less likely to be using a CHC and this group may also be more symptomatic. Epidemiologic studies do not find that the expression of symptoms varies by age cohort,27 but clinically, older women of child-bearing potential seem to present more often than younger women.

Conclusions

In sum, there were minor differences in premenstrual symptom severity between women who did or did not use CHC, decreasing the likelihood that women who use CHC will have the premenstrual change severity that meets criteria for moderate to severe PMS. However, the most symptomatic window and response to treatment were the same for women with moderate to severe PMS regardless of CHC use. This suggests that there is little reason to exclude women who use CHC from future nonhormonal treatment studies for PMS. We again find that whether women retrospectively report problems with premenstrual symptoms or meet prospective criteria for PMDD, they continue to be symptomatic during the first few days of their menstrual period. This suggests that intermittent treatments should include these symptomatic days.

Condensation and Short Version of Title

Effects of cyclic hormone contraception on premenstrual syndrome

Compared with women with natural cycles, those undergoing cyclic hormone contraception experience peak symptoms at the same time, but have slightly milder peak perimenstrual symptoms.

Appendix Table A1.

Mean Effect Size for OCP Groups by Symptom Subgroup During Four Time Intervals

| Days (−6,−1) | Days (−5,1) | Days (−4,2) | Days (−3,3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | |

| Screened cohort | N = 387 | N = 103 | N = 387 | N = 103 | N = 387 | N = 103 | N = 387 | N = 103 |

| Depressed, hopeless, and guilty | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.07 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.08 |

| Anxious, tense | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.07 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.08 |

| Mood swings or sensitivity to rejection | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.08 |

| Anger or irritability | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.75 ± 0.08 |

| Diminished interest | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.07 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.08 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.08 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.67 ± 0.08 |

| Lethargy | 0.79 ± 0.04 | 0.80 ± 0.07 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.08 |

| Increased appetite or cravings | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.70 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.08 |

| Increased or decreased sleep | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.08 | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.64 ± 0.08 |

| Felt overwhelmed or out of control | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.08 | 0.69 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.08 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.56 ± 0.08 |

| Breast discomfort, headache, or muscle pains | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.08 |

Linear mixed-effects models used to estimate differences in OCP and non-OCP groups for DSM 5 symptoms by four premenstrual time intervals ((−6,-1), (−5,1), (−4,2), (−3,3)).

Appendix Table A2.

Mean Effect Size for OCP Groups by Symptom Subgroup During Four Time Intervals

| Days (−6,−1) | Days (−5,1) | Days (−4,2) | Days (−3,3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | Non-OCP LS mean ± SE | OCP LS mean ± SE | |

| Randomized cohort | N = 211 | N = 41 | N = 211 | N = 41 | N = 211 | N = 41 | N = 211 | N = 41 |

| Depressed, hopeless, and guilty | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.10 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.98 ± 0.11 |

| Anxious, tense | 1.24 ± 0.04 | 1.18 ± 0.10 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.11 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.27 ± 0.11 | 1.23 ± 0.05 | 1.29 ± 0.11 |

| Mood swings or sensitivity to rejection | 1.24 ± 0.04 | 1.40 ± 0.10 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.47 ± 0.11 | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 1.48 ± 0.11 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.44 ± 0.11 |

| Anger or irritability | 1.22 ± 0.04 | 1.21 ± 0.10 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.28 ± 0.11 | 1.31 ± 0.05 | 1.29 ± 0.11 | 1.24 ± 0.05 | 1.26 ± 0.11 |

| Diminished interest | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.10 | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.11 | 1.31 ± 0.05 | 1.25 ± 0.11 | 1.28 ± 0.05 | 1.30 ± 0.11 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 1.07 ± 0.04 | 1.19 ± 0.10 | 1.14 ± 0.05 | 1.19 ± 0.11 | 1.18 ± 0.05 | 1.31 ± 0.11 | 1.14 ± 0.05 | 1.31 ± 0.11 |

| Lethargy | 1.13 ± 0.04 | 1.32 ± 0.10 | 1.27 ± 0.05 | 1.41 ± 0.11 | 1.33 ± 0.05 | 1.43 ± 0.11 | 1.32 ± 0.05 | 1.41 ± 0.11 |

| Increased appetite or cravings | 1.15 ± 0.05 | 1.12 ± 0.10 | 1.17 ± 0.06 | 1.23 ± 0.11 | 1.18 ± 0.05 | 1.28 ± 0.11 | 1.11 ± 0.05 | 1.28 ± 0.11 |

| Increased or decreased sleep | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 1.03 ± 0.10 | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.11 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | 1.14 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 1.14 ± 0.11 |

| Felt overwhelmed or out of control | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.10 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 1.03 ± 0.05 | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 1.05 ± 0.11 |

| Breast discomfort, headache, or muscle pains | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 1.06 ± 0.10 | 1.13 ± 0.06 | 1.16 ± 0.11 | 1.18 ± 0.05 | 1.18 ± 0.11 | 1.13 ± 0.05 | 1.16 ± 0.11 |

Linear mixed-effects models used to estimate differences in OCP and non-OCP groups for DSM 5 symptoms by four premenstrual time intervals ((−6,-1), (−5,1), (−4,2), (−3,3)).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants R01 MH072955 (PI Yonkers), MH072645 (PI Kornstein), and MH072962 (PI Altemus) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Yonkers discloses royalties from UpToDate and consulting to Pontifax; Dr. Gueorguieva discloses consulting fees from Palo Alto Health Sciences and Mathematica Policy Research; Dr. Kornstein discloses research support from Palatin Technologies, Takeda, Allergan, Forest, Roche, and Pfizer; consulting or participation in advisory boards for Palatin Technologies, Takeda, Allergan, Forest, Naurex, Pfizer, Lilly, Shire, and Sunovion; and royalties from Guilford Press; and Dr. Altemus and Ms. Cameron have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.ACOG. ACOG issues guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of PMS. 2003. www.acog.org/patients/FAQs/premenstrual-syndrome-PMS Accessed May1, 2015

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurt SW, Schnurr PP, Severino SK, et al. Late luteal phase dysphoric disorder in 670 women evaluated for premenstrual complaints. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartlage SA, Arduino KE. Toward the content validity of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Do anger and irritability more than depressed mood represent treatment seekers experiences? Psychol Rep 2002;90:189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:465–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yonkers KA, Brown C, Pearlstein TB, Foegh M, Sampson-Landers C, Rapkin A. Efficacy of a new low-dose oral contraceptive with drospirenone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:492–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearlstein TB, Bachmann GA, Zacur HA, Yonkers KA. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with a new drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive formulation. Contraception 2005;72:414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halbreich U, Freeman EW, Rapkin AJ, et al. Continuous oral levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol for treating premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Contraception 2012;85:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Backstrom T, Hansson-Malmstrom Y, Lindhe B-A, Cavalli-Bjorkman B, Nordenstrom S. Oral contraceptives in premenstrual syndrome: A randomized comparison of triphasic and monophasic preparations. Contraception 1992;46:253–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham CA, Sherwin BB. A prospective treatment study of premenstrual symptoms using a triphasic oral contraceptive. J Psychosom Res 1992;36:257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman EW. Evaluation of a unique oral contraceptive (Yasmin) in the management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2002;7:27–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien PMS, Backstrom T, Brown C, et al. Towards a consensus on diagnostic criteria, measurement and trial design of the premenstrual disorders: The ISPMD Montreal consensus. Arch Womens Ment Health 2011;14:13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham SS. Oral contraception and cyclic changes in premenstrual and menstrual experiences. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2003;24:185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersch B, Hahn L. Premenstrual complaints II. Influence of oral contraceptives. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1981;60:579–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle GJ, Grant AF. Prospective versus retrospective assessment of menstrual cycle symptoms and moods: Role of attitudes and beliefs. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 1992;14:307–321 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marriott A, Faragher EB. An assessment of psychological state associated with the menstrual cycle in users of oral contraception. J Psychosom Res 1986;30:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paige KE. Effects of oral contraceptives on affective fluctuations associated with the menstrual cycle. Psychosom Med 1971;33:515–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross C, Coleman G, Stojanovska C. Factor structure of the modified Moos Menstrual Distress Questionnaire: Assessment of prospectively reported follicular, menstrual and premenstrual symptomatology. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2003;24:163–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sveinsdottir H, Backstrom T. Menstrual cycle symptom variation in a community sample of women using and not using oral contraceptives. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:757–764 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilcoxon LA, Schrader SL, Sherif CW. Daily self-reports on activities, life events, moods, and somatic changes during the menstrual cycle. Psychosom Med 1976;38:399–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker A, Bancroft J. Relationship between premenstrual symptoms and oral contraceptive use: A controlled study. Psychosom Med 1990;52:86–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yonkers KA, Kornstein SG, Gueorguieva R, Merry B, Van Steenburgh K, Altemus M. Symptom-onset dosing of sertraline for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:1037–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartlage SA, Freels S, Gotman N, Yonkers K. Criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Secondary analyses of relevant data sets. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:300–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnurr PP. Measuring amount of symptom change in the diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome. Psycholog Assess 1989;1:277–283 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warner P, Bancroft J. Mood, sexuality, oral contraceptives and the menstrual cycle. J Psychosom Res 1988;32:417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wittchen H, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol Med 2002;32:119–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]