Abstract

Objectives: Parental experiences with managing their child's attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can influence priorities for treatment. This study aimed to identify the ADHD management options caregivers most prefer and to determine if preferences differ by time since initial ADHD diagnosis.

Methods: Primary caregivers (n = 184) of a child aged 4–14 years old in care for ADHD were recruited from January 2013 through March 2015 from community-based pediatric and mental health clinics and family support organizations across the state of Maryland. Participants completed a survey that included child/family demographics, child clinical treatment, and a Best–Worst Scaling (BWS) experiment to elicit ADHD management preferences. The BWS comprised 18 ADHD management profiles showing seven treatment attributes, where the best and worst attribute levels were selected from each profile. A conditional logit model using effect-coded variables was used to estimate preference weights stratified by time since ADHD diagnosis.

Results: Participants were primarily the mother (84%) and had a college or postgraduate education (76%) with 75% of the children on stimulant medications. One-on-one caregiver behavior training, medication use seven days a week, therapy in a clinic, and an individualized education program were most preferred for managing ADHD. Aside from caregiver training and monthly out-of-pocket costs, caregivers of children diagnosed with ADHD for less than two years prioritized medication use lower than other care management attributes and caregivers of children diagnosed with ADHD for two or more years preferred school accommodations, medication, and provider specialty.

Conclusions: Preferences for ADHD treatment differ based on the duration of the child's ADHD. Acknowledging that preferences change over the course of care could facilitate patient/family-centered care planning across a range of resources and a multidisciplinary team of professionals.

Keywords: : stated preferences, best worst scaling, caregivers, patient-centered care

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is reported among 10% (6.4 million) U.S. children and adolescents and half, or 3.5 million, use first-line stimulant medication (Visser et al. 2014). ADHD is the only neurodevelopmental childhood disorder with a treatment that has an extensive evidence base from clinical trials. However, there has been relatively poor adherence to treatment (Adler and Nierenberg 2010) even though, for many children, ADHD is a chronic condition. Often treated in pediatric practice (Goodwin et al. 2001), the American Academy of Pediatrics supports management by primary care providers, care planning guided by patient/family preferences (Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Task Force on Mental Health 2009; Wolraich et al. 2011), and treatment outcomes elicited by families' and children's priorities (Foy 2010).

A better understanding of the issues that most influence patients and families is needed (Nielsen 2014). For one, although stimulants to reduce hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention and parent training to manage the child's ADHD behaviors at home are supported by randomized, controlled clinical trials and are emphasized in evidence-based guidelines (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2002; Wolraich et al. 2011), families often prefer nonpharmacologic alternatives, avoiding stimulants until all other efforts have failed (Bussing et al. 2002; Leslie et al. 2007; dosReis et al. 2009; Coletti et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2012). Previous research demonstrates that caregivers of children newly diagnosed with ADHD are coming to terms with how to best manage the behaviors for up to four years (dosReis et al. 2007, 2009). Moreover, practice guidelines are specific to the care management of children as young as four to five years old, yet studies on parent preferences for ADHD treatment generally focus on children aged six years and older and those newly diagnosed rather than those who have been in care for several years (Waschbusch et al. 2011; Fiks et al. 2013). Additionally, the communication between pediatricians, mental health specialists, and school personnel for ADHD care management can be challenging for providers and families (Lynch et al. 2015).

The purpose of the present study was to elicit from the caregiver the relative preference for the components of an ADHD treatment plan, which consisted of seven different care management attributes (i.e., days medication is used, location where behavior therapy is provided, type of provider managing the ADHD, accommodations in school, communication with provider, caregiver behavior training, and out-of-pocket costs). Acknowledging that personal experiences over the course of the child's ADHD influence treatment decisions (Brinkman and Epstein 2011; Coletti et al. 2012) more so than the child's gender or age (Secnik et al. 2005), the main objective was to determine if priorities for specific ADHD treatment attributes differ between less experienced caregivers of a child newly diagnosed with ADHD versus caregivers who are more experienced in managing their child's existing chronic ADHD. The duration of the child's ADHD diagnosis served as a proxy for caregivers' experience in managing ADHD. Although highly correlated with the child's age, duration of the ADHD diagnosis is more precise since symptom severity or functional impairment may not reach the threshold for diagnosis until late childhood. Knowledge of preferences for ADHD management options and any difference in priorities for treatment based on caregivers' experience managing their child's ADHD could enhance the delivery of patient/family-centered care. For example, this could inform the treatment options that providers discuss with individual caregivers or it could identify the design of more patient and family-centered service delivery systems. We hypothesized that medication use would be prioritized differently by caregivers of a child diagnosed with ADHD less than two years versus two or more years.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study of caregivers' preferences for managing their child's ADHD care. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Caregivers of children aged four to 14 years old were eligible if his/her child was being treated for ADHD at the time of study entry. This ensured that participants had sufficient experience with treatment and service delivery to inform preferences. Caregivers were recruited from January 2013 through March 2015 from primary care and mental health specialty pediatric outpatient clinics, a statewide caregiver support organization, and the parent support teams based in the public school system throughout Maryland. Anyone unable to provide written consent due to a cognitive impairment or who did not speak English was not enrolled. Mother and father dyads were both able to participate since each would have a unique preference for treatment.

Caregivers reported the time, in months or years, since his/her child was first diagnosed with ADHD. Those with a child diagnosed with ADHD for less than two years (n = 45) were considered less experienced with treatment, while those with a child diagnosed with ADHD for two or more years (n = 139) were considered more experienced with the chronic management of ADHD. The two-year cutoff was motivated by several factors. For one, many caregivers perceive ADHD as a school-related problem (dosReis et al. 2009) and the distinct encounters in school within the first two years following an initial ADHD diagnosis can influence preferences. For example, in two years, a caregiver typically experiences at least two classrooms and two different teachers, and consistent reports from both teachers could affect caregivers' perceptions of ADHD care management. Second, following an initial ADHD diagnosis, obtaining an individualized education program (IEP) for their child involves an intensive evaluation process that may take several months and cross two academic years, which also could shift treatment preferences.

Survey instrument

The survey used in the present study to elicit ADHD care management preferences was piloted previously (dosReis et al. 2015). The computer-based survey captured (1) current care, (2) treatment preferences, (3) demographic characteristics, and (4) clinical treatment.

Participants indicated which level of each ADHD treatment attribute (Table 2) described their child's current care plan. These questions were informed from feedback during the pilot study (dosReis et al. 2015). Medication use referred to the days when medication was administered, which is how caregivers view the need for medication (dosReis et al. 2009) because this is one of the few psychotropic medications that may be started or stopped acutely. Since caregivers in the pilot study indicated the importance of where behavioral therapy was provided, the response options were home, school, or clinic. School accommodations were based on the most intensive, that is, IEP, to the least intensive, that is, progress notes from the teacher. Caregiver behavior training also ranged from the most intensive, that is, one-on-one with a therapist, to the least intensive, that is, learning on one's own. Caregivers in the pilot study (dosReis et al. 2015) noted the importance of the type of provider managing their child's ADHD and how they communicated with the provider. Therefore, provider types included pediatrician, psychiatrist, or both pediatrician and psychiatrist, which would shed light on preferences for integrated care. Communication method (i.e., face-to-face, telephone, or text/email) reflected preferences for engagement in care. Finally, participants considered monthly out-of-pocket costs, including indirect costs such as childcare, time out of work, and transportation.

Table 2.

Best and Worst Selections for Each Attribute Level Stratified by Duration of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

| Overall | ADHD diagnosed <2 years | ADHD diagnosed >2 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute level | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Pdiagnosed<2 year = diagnosed>2years |

| Medication administration | |||||||

| ADHD medicine is used 5 days a week on school days only | 0.037 | 0.067 | −0.016 | 0.131 | 0.053 | 0.078 | 0.648 |

| ADHD medicine is used 7 days a week except in summer | −0.391 | 0.066 | −0.277 | 0.125 | −0.429 | 0.078 | 0.304 |

| ADHD medicine is used 7 days a week all year round | 0.354 | 0.071 | 0.293 | 0.133 | 0.376 | 0.083 | 0.617 |

| Therapy location | |||||||

| Child gets therapy in the clinic | 0.184 | 0.046 | 0.403 | 0.099 | 0.115 | 0.051 | 0.010a |

| Child gets therapy in school | −0.097 | 0.047 | −0.326 | 0.101 | −0.024 | 0.053 | 0.008a |

| Child gets therapy at home | −0.087 | 0.046 | −0.077 | 0.098 | −0.091 | 0.052 | 0.898 |

| School accommodation | 0.000 | ||||||

| Child's teacher sends home progress note | −0.424 | 0.048 | −0.210 | 0.097 | −0.494 | 0.056 | 0.011a |

| Child gets a tutor at school | −0.114 | 0.047 | −0.329 | 0.085 | −0.043 | 0.055 | 0.005a |

| Child has an IEP | 0.538 | 0.052 | 0.539 | 0.095 | 0.537 | 0.062 | 0.988 |

| Caregiver behavior training | |||||||

| Caregiver learns behavior management on own | −0.837 | 0.046 | −1.006 | 0.092 | −0.785 | 0.053 | 0.037a |

| Caregiver learns behavior management 1:1 with a therapist | 0.812 | 0.049 | 0.869 | 0.097 | 0.795 | 0.057 | 0.511 |

| Caregiver learns behavior management by going to a class | 0.025 | 0.046 | 0.137 | 0.091 | −0.011 | 0.054 | 0.729 |

| Provider communication | |||||||

| Talk with provider by text/email | −0.378 | 0.042 | −0.319 | 0.094 | −0.398 | 0.047 | 0.451 |

| Talk with provider by phone | −0.093 | 0.040 | −0.171 | 0.089 | −0.069 | 0.045 | 0.304 |

| Talk with provider face-to-face | 0.472 | 0.040 | 0.490 | 0.095 | 0.467 | 0.044 | 0.806 |

| Provider specialty | |||||||

| Pediatrician cares for child's ADHD | −0.481 | 0.047 | −0.779 | 0.102 | −0.386 | 0.052 | 0.001b |

| Psychiatrist cares for child's ADHD | 0.082 | 0.048 | 0.261 | 0.105 | 0.025 | 0.054 | 0.046a |

| Pediatrician and psychiatrist care for child's ADHD | 0.399 | 0.049 | 0.518 | 0.105 | 0.361 | 0.056 | 0.169 |

| Monthly out-of-pocket costs | |||||||

| Out of pocket cost is $50/month | 0.883 | 0.053 | 0.800 | 0.111 | 0.912 | 0.061 | 0.380 |

| Out of pocket cost is $150/month | 0.013 | 0.056 | 0.139 | 0.111 | −0.028 | 0.065 | 0.195 |

| Out of pocket cost is $450/month | −0.896 | 0.054 | −0.939 | 0.109 | −0.884 | 0.063 | 0.663 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IEP, individualized education program; SD, standard deviation.

A Best–Worst Scaling (BWS) instrument was used to elicit preferences for different attributes of an ADHD care management profile. Methodologically, BWS is more rigorous than traditional Likert response scales (Van Brunt et al. 2011; Fiks et al. 2013), which does not distinguish trade-offs among attributes; yet, there is evidence to suggest individuals value attributes differently (Waschbusch et al. 2011; dosReis et al. 2015; Ross et al. 2015). BWS prompts individuals to weigh the benefits and risks of the levels of different attributes, acknowledges that attributes are not valued equally, and reflects real-world decision-making (Matza et al. 2005; Secnik et al. 2005; Muhlbacher et al. 2009; Muhlbacher and Nubling 2010; Fegert et al. 2011; Lloyd et al. 2011; Nafees et al. 2014). Second, most studies focus solely on eliciting preferences for symptom control, the medication's duration of effect, and the medication's side effects (Muhlbacher et al. 2009; Muhlbacher and Nubling 2010; Fegert et al. 2011; Lloyd et al. 2011; Nafees et al. 2014; Schatz et al. 2015). One other study examined a range of evidence-based ADHD treatments by varying the dose (none, low, high) of medication, behavior modification, parent training interventions, and treatment outcomes (Waschbusch et al. 2011).

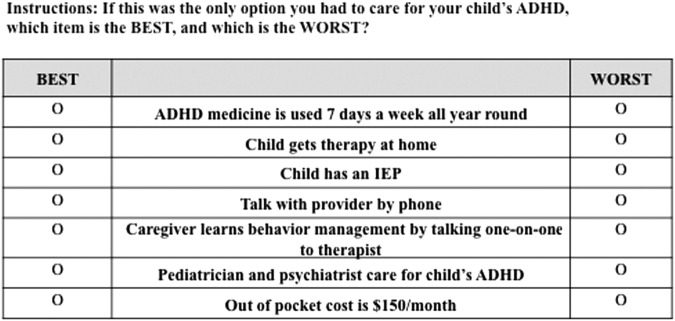

The BWS presents a hypothetical treatment plan that forces individuals to make a choice between one best and one worst attribute from a set of competing care management alternatives presented in a profile (Fig. 1). Conceptually, selecting the two items furthest apart is more precise than ranking attributes because the relative difference between the mid-ranked items becomes less clear (Louviere and Flynn 2010). The SAS database (Kuhfeld 2010) was used to identify a profile design that balanced the number of opportunities any one attribute could be selected as well as the number of times any two attribute levels appeared together as competing alternatives. Each attribute level was shown six times over the 18 profile sets (i.e., questions).

FIG. 1.

Example of a BWS choice task profile for a hypothetical ADHD care management plan. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BWS, Best–Worst Scaling.

Participants reported his/her relationship with the child, age, gender, race, education, annual household income, health insurance type, individuals living in the same household, marital status, and occupation. Child-level information included age, gender, years since diagnosed with ADHD, stimulant and other psychotropic medications, and receipt of therapy. The Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale (VADPRS) assessed self-reported ADHD symptoms as well as symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder, anxiety and depression, and impairment in academic performance and relationships (Wolraich et al. 2003). Participants completed the VADPRS according to the observed behaviors off medication.

Study procedures

The project coordinator (X.N.) screened individuals by phone and scheduled face-to-face visits with those who were eligible. Surveys were completed at the clinic or other community-based setting (e.g., public library). After reviewing the study's purpose, what would be expected of those who joined the study, and what individuals could do if they no longer wanted to be in the study, written consent was obtained. A research assistant reviewed the instructions, so participants knew how to complete the BWS questions. The entire assessment took ∼45 minutes and participants received a $25 gift card.

Data analyses

Survey responses were downloaded as Excel® files, checked for errors, and converted to SAS 9.3 and Stata 13 datasets for analyses. Bivariate chi-square analyses assessed statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics between caregivers and children diagnosed with ADHD for less than two versus two or more years. A choice model was estimated for the aggregate sample and stratified by duration of ADHD diagnosis of less than two years versus two or more years.

A sequential best–worst choice model was estimated, in which we assumed that participants first chose the best attribute and then the worst attribute from each profile (Flynn 2010). In practice, these assumptions produce similar estimates as a worst–best assumption or maximum difference model in which the respondents choose the attribute pair that maximizes their best–worst difference (Marley and Louviere 2005; Flynn et al. 2008).

The choice model was estimated using a conditional logit model (McFadden 1974). In the choice model, the dependent variable indicated whether an attribute level was chosen as best or worst for a given choice task. The levels of each attribute in the choice task served as independent variables. Attribute levels were effect coded. With effect coding, zero represents the mean effect across all attribute levels and a parameter estimate for all levels can be computed; the omitted attribute parameter is the negative sum of the included attribute parameters.

We stratified the choice model by duration of ADHD diagnosis. A Wald test was used to examine the equivalence of the stratified choice models. Paired t-tests were used to test for the equivalence of individual coefficients between educational groups. In addition, a Louviere–Swait test (Swait and Louviere 1993) was conducted to examine whether observed differences in preferences could be attributed to scale. Scale differences signal that observed differences between the groups are due to differences in error variance, or consistency in completing the choice tasks, and not due to underlying differences in preferences.

Preference weights were then used to identify the importance of an attribute conditional on all other attributes. Since selections were for attribute levels (e.g., medication use five days a week) and not the overall attribute (e.g., medication administration), the preference weights could not be used directly to estimate conditional attribute importance (i.e., medication administration is more important than school accommodation). Rather, the magnitude of difference between the highest and the lowest preference weight for each level within the attribute (i.e., minimum–maximum difference) was calculated. A large minimum–maximum difference resulted when one level was selected more often than other levels within an attribute and thereby discriminated preferences. A small minimum–maximum difference meant that each level was selected approximately the same number of times, which did not discriminate preferences. The minimum–maximum difference for each attribute was summed to get the total variance. The proportion of the total variance explained by any one attribute determines conditional attribute importance. Conditional attribute importance was calculated for each ADHD duration subgroup.

Results

Participant characteristics

The response rate was 61% and nearly all 184 participants were the child's mother. The racial distribution reflected the overall demographics in the state of Maryland (i.e., 68% white and 25% African American/black). The majority were aged 40 years or less, married, and two-parent households. Most attained a college or postgraduate education and reported annual household income greater than $75,000. Participant characteristics were not statistically different between those who had a child diagnosed with ADHD two or more versus less than two years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the 184 Caregivers and 182 Children

| Caregiver characteristicsf | Overall (n = 184) N (%) | ADHD diagnosed <2 years (n = 45) N (%) | ADHD diagnosed ≥2 years (n = 139) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racea | |||

| White | 125 (68) | 36 (80) | 89 (64) |

| African American/Black | 46 (25) | 7 (16) | 39 (28) |

| Other | 13 (7) | 2 (4) | 11 (8) |

| Agea, years | |||

| 27–40 | 88 (48) | 27 (60) | 61 (44) |

| 41–50 | 73 (40) | 15 (33) | 58 (42) |

| 51–70 | 23 (12) | 3 (7) | 20 (14) |

| Mean (SD), yearsb | 41.8 (8.5) | 39.0 (7.9) | 42.7 (8.5) |

| Relationship with the child | |||

| Mother | 155 (84) | 36 (80) | 119 (86) |

| Father | 8 (4) | 3 (6) | 5 (4) |

| Grandmother/aunt | 12 (7) | 3 (7) | 9 (6) |

| Foster/adopted parent | 9 (5) | 3 (7) | 6 (4) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 192 (65) | 27 (60) | 92 (66) |

| Never married/divorced/widowed | 65 (35) | 18 (40) | 47 (34) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 44 (24) | 11 (25) | 33 (24) |

| College | 80 (43) | 19 (42) | 61 (44) |

| Postgraduate | 60 (33) | 15 (33) | 45 (32) |

| Annual household income | |||

| <$25k | 32 (17) | 7 (16) | 25 (17) |

| $26 to 50k | 36 (20) | 10 (22) | 26 (19) |

| $51 to 75k | 32 (17) | 6 (13) | 26 (19) |

| >$75k | 84 (46) | 22 (49) | 62 (45) |

| Occupation | |||

| Professional | 56 (30) | 17 ((38) | 39 (28) |

| Skilled | 51 (28) | 11 (24) | 40 (29) |

| Unskilled | 22 (12) | 5 (11) | 17 (12) |

| Retired/not working | 55 (30) | 12 (26) | 43 (31) |

| Household composition | |||

| Two-parent family | 118 (64) | 28 (62) | 90 (65) |

| Single-parent family | 53 (29) | 14 (31) | 39 (28) |

| Extended family | 13 (7) | 3 (7) | 10 (7) |

| Insurance type | |||

| Private | 102 (55) | 26 (58) | 75 (54) |

| Public | 82 (45) | 19 (42) | 64 (46) |

| Child characteristicsf | Overall (n = 182) N (%) | ADHD diagnosed <2 years (n = 45) N (%) | ADHD diagnosed ≥2 years (n = 139) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agec | |||

| <10 years | 92 (51) | 34 (77) | 58 (42) |

| 10 years or older | 90 (49) | 10 (23) | 80 (58) |

| Mean (SD), years | 9.7 (3) | 8.1 (2.3) | 10.2 (2.4) |

| Genderd | |||

| Male | 129 (70) | 29 (67) | 100 (75) |

| Female | 47 (26) | 14 (33) | 33 (25) |

| Duration of ADHD | |||

| Mean (SD), years | 3.7 (3) | 0.94 (0.36) | 4.6 (2.4) |

| VADPRS symptoms | |||

| ADHD | 55 (30) | 10 (23) | 45 (33) |

| Inattentive | 9 (5) | 3 (7) | 6 (4) |

| Hyperactive/impulsive | 87 (48) | 23 (52) | 64 (46) |

| Combined type | 31 (17) | 8 (18) | 23 (17) |

| No ADHD | |||

| ODD | 103 (57) | 24 (55) | 79 (57) |

| CD | 26 (14) | 5 (11) | 21 (15) |

| Anxiety/depression | 65 (36) | 17 (39) | 48 (35) |

| Provider | |||

| Pediatrician | 60 (33) | 11 (26) | 49 (40) |

| Psychiatrist | 79 (43) | 20 (48) | 59 (48) |

| Pediatrician/psychiatrist | 26 (14) | 11 (26) | 15 (12) |

| Current ADHD medication | |||

| Any ADHD medicatione | 148 (81) | 33 (73) | 115 (83) |

| Stimulanta | 137 (75) | 28 (64) | 109 (79) |

| Alpha-Agonists | 34 (19) | 4 (9) | 30 (22) |

| Other psychotropic medication | |||

| Any psychotropic medication | 35 (19) | 7 (16) | 28 (20) |

| Antipsychotics | 14 (8) | 1 (2) | 13 (9) |

| Antidepressants | 18 (10) | 5 (11) | 13 (9) |

| Mood-stabilizing anticonvulsants | 13 (7) | 3 (7) | 10 (7) |

| Treatment modality | |||

| Medication only | 56 (31) | 9 (20) | 47 (34) |

| Therapy only | 17 (9) | 7 (16) | 10 (7) |

| Medication and therapy | 96 (53) | 25 (57) | 71 (52) |

| No treatment | 13 (7) | 3 (7) | 10 (7) |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.0001.

Missing data on gender for six children.

Includes atomoxetine and alpha-agonist.

Child characteristics, percentage of 182 children.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD, conduct disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; SD, standard deviation; VADPRS, Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale.

Participants reported on 182 children (Table 1), with two mother–father dyads reporting on the same child. Overall, the male-to-female ratio of children was 3:1 and children had been diagnosed with ADHD, on average, for just under four years. According to the VADPRS, most children were classified as combined-type ADHD. Some (17%) did not feel their child displayed the core symptoms of ADHD despite a clinician-assigned diagnosis and currently in care for ADHD. Symptoms were noted for ODD (57%) and anxiety/depression (36%). With the exception of age, child demographic characteristics were not statistically significantly different comparing participants of a child diagnosed with ADHD less than two years versus two or more years.

Current treatment

The majority (53%) of children received both medication and behavioral therapy at the time of the survey (Table 1). Behavioral therapy alone or in combination with medication was used by 73% of children diagnosed with ADHD for fewer than two years compared with 59% of children diagnosed with ADHD for two or more years. Most children (81%) were using a stimulant or an alpha-agonist with 19% also taking other psychotropic medications. Children who were diagnosed with ADHD less than two years were less likely to receive stimulants (64%) than children who were diagnosed with ADHD for two or more years (79%; p < 0.05). Treatment modality and provider specialty were not significantly different among children diagnosed with ADHD for two or more years versus fewer than two years.

Preference estimates

The Wald test for difference between models was significant (p = 0.0002), even after adjusting for possible scale (p = 0.0033). Thus, results suggest that the observed differences are not due to error variance between the groups. The preference weights and standard errors are presented in Table 2 for the sample overall and stratified by caregivers of a child diagnosed with ADHD less than two versus two or more years. The highest mean scores within each attribute were medication seven days per week all year round, therapy provided in a clinic, an IEP school accommodation, one-on-one caregiver behavior training with a therapist, and the comanagement of a pediatrician and psychiatrist.

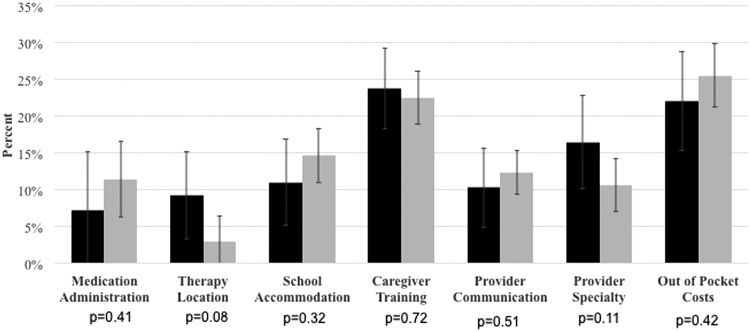

Attribute importance

Conditional attribute importance, stratified by the duration of the child's ADHD, is displayed in Figure 2 as the percent that each attribute contributes to the total variance between minimum and maximum mean scores across all attributes. Regardless of the duration of the child's ADHD diagnosis, variation in monthly out-of-pocket costs and caregiver behavioral training exerted the most influence on participants' treatment choices. For caregivers of children who had been diagnosed for two or more years, medication was ranked fourth in order of importance, while medication was ranked last for those who had a child diagnosed with ADHD for less than two years. The absolute percent difference between groups for each attribute was not significantly different.

FIG. 2.

Relative importance of ADHD care management attributes according to the duration of the child's diagnoses. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Discussion

This research demonstrated that caregivers' preferences for a range of ADHD treatments differ. Variations in approaches to caregiver behavior training exerted a relatively important influence on treatment plan choices than other aspects of an ADHD management plan. However, it is more difficult for providers and families to access evidence-based behavioral services in outpatient settings than it is to access medication. With evidence supporting collaborative care on patient outcomes (Asarnow et al. 2015), this is a clinically relevant gap in our healthcare system. Since obtaining an IEP can take several months, knowing the relative importance of medication and school accommodations in the course of illness would help providers sequence treatment planning and optimize patient/family-centered care. Finally, the current study addressed preferences for a range of modifiable interventions, such as days when medication is used, provider managing the child's ADHD, caregiver behavior management training, and the cost of care, which offers new information that is clinically relevant to patient-centered care.

The current findings can be used to promote shared decision-making, minimize concerns, and improve satisfaction with care, acutely and over time. For one, making informed health decisions is a top priority for caregivers of children with serious medical needs (Feudtner et al. 2015). Second, personal experiences with ADHD and different treatment modalities influence treatment decisions over time (dosReis et al. 2007, 2010; Leslie et al. 2007; dosReis and Myers 2008; Brinkman and Epstein 2011; Coletti et al. 2012). Finally, willingness to use stimulants is tempered by caregivers' perceptions that it is overused, is ineffective, has harmful side effects, can lead to future substance abuse, and lack of satisfaction with treatment (dosReis et al. 2003, 2009; Bussing et al. 2012; Coletti et al. 2012; Glenngard et al. 2013). Consideration of these issues could facilitate family-centered shared decision-making.

Treatment priorities should be considered in light of the existing evidence-based and practical constraints. The Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) study supported medication as the best treatment, yet this effect decreased over the observational follow-up when some may have started or stopped medication (The MTA Cooperative Group 2004). This change in preference for medication with duration of the child's ADHD also was evident in the present study. Caregiver behavior management training was important regardless of the child's age or duration of the ADHD diagnosis, whereas school support was less important early in the course of care (dosReis et al. 2010). The considerable caregiver stress accompanied by limited social support (Bussing et al. 2003) highlights the significance of addressing the caregivers' needs, including appropriate referral and access to services, in the context of managing the child's ADHD (Zickafoose et al. 2015). Moreover, variation in the format of communication with providers had a relatively important influence on caregivers of a child diagnosed with ADHD for less than two years, yet communication among providers and with families has been difficult in primary care settings (Lynch et al. 2014). Finally, the present study suggests that additional costs beyond insurance coverage, such as time away from work and child care expenses, could have large negative effects on engagement.

The study has several limitations. Since all participants had a child currently in care for ADHD, the findings do not generalize to families whose child is treatment naïve; a population where research is needed. The sample was drawn from upper middle-class families in one state, which may not extrapolate to families that are less stable financially or have limited access to healthcare resources. The range of attribute levels that were presented may have influenced conditional attribute importance. The study only captured adult caregiver preferences, yet adolescent preferences are important for engagement in care planning and adherence.

Conclusions

Caregivers' experiences managing their child's ADHD over time can influence their preferences for components of evidence-based treatments. Understanding which aspects of the care management plan are preferred at different time points over the course of care can be achieved with ongoing caregiver–provider communications about preferences.

Clinical Significance

These findings also have clinical implications for implementing best practices within an integrated behavioral health and primary care medical home (Silverstein et al. 2015). For example, therapy location, medication administration frequency, and school accommodations had an important influence on preferences for caregivers at different time points in care. This information could assist providers and caregivers in tailoring treatment plans toward the families' values and ultimately improving child and family outcomes.

Disclosures

S.d.R., E.F., G.R., J.B., A.P., X.N., and E.J. have nothing to disclose. S.d.R., E.F., G.R., J.B., and X.N. were supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. C.C.'s participation was supported by the Jack Laidlaw Chair in Patient-Centered Healthcare. He has conducted workshops on COPE, a parenting program for families of children with externalizing problems, and received royalties on COPE leader training videos and manuals.

References

- Adler LD, Nierenberg AA: Review of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHD. Postgrad Med 122:184–191, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Practice parameters for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41(2 Suppl):26S–49S, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Rozenman M, Wiblin J, Zeltzer L: Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 169:929–937, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Epstein JN: Treatment planning for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Treatment utilization and family preferences. Patient Prefer Adherence 5:45–56, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg M, Noguchi K, Mason D, Mayerson G, Garvan CW: Willingness to use ADHD treatments: A mixed methods study of perceptions by adolescents, parents, health professionals and teachers. Soc Sci Med 74:92–100, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Garvan CW: Use of complementary and alternative medicine for symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Serv 53:1096–1102, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Mason DM, Leon CE, Sinha K, et al. : Social networks, caregiver strain, and utilization of mental health services among elementary school students at high risk for ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:842–850, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Task Force on Mental Health. Policy statement—The future of pediatrics: Mental health competencies for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics 124:410–421, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coletti DJ, Pappadopulos E, Katsiotas NJ, Berest A, Jensen PS, Kafantaris V: Parent perspectives on the decision to initiate medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:226–237, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CC, Claudius M, Palinkas LA, Wong JB, Leslie LK: Putting families in the center: Family perspectives on decision making and ADHD and implications for ADHD care. J Atten Disord 16:675–684, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Barksdale CL, Sherman A, Maloney K, Charach A: Stigmatizing experiences of parents of children newly diagnosed with ADHD. Psychiatr Serv 61:811–816, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Evans-Lacko SE, Beltran A, Riley AW, Myers MA: The meaning of ADHD medication and parents' initiation and continuity of treatment for their child. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 19:377–383, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Myers MA, Riley AW: Coming to terms with ADHD: How urban African-American families come to seek care for their children. Psychiatr Serv 58:636–641, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Myers MA: Parental attitudes and involvement in psychopharmacological treatment for ADHD: A conceptual model. Int Rev Psychiatry 20:135–141, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Ng X, Frosch E, Reeves G, Cunningham C, Bridges JF: Using best-worst scaling to measure caregiver preferences for managing their child's ADHD: A pilot study. Patient 8:423–431, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL, Mitchell JW, Ellwood LC: Parental perceptions and satisfaction with stimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr 24:155–162, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegert JM, Slawik L, Wermelskirchen D, Nubling M, Muhlbacher A: Assessment of parents' preferences for the treatment of school-age children with ADHD: A discrete choice experiment. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 11:245–252, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, Hill DL, Carroll KW, Mollen CJ, et al. : Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr 169:39–47, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiks AG, Mayne S, Debartolo E, Power TJ, Guevara JP: Parental preferences and goals regarding ADHD treatment. Pediatrics 132:692–702, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn TN: Valuing citizen and patient preferences in health: Recent developments in three types of best-worst scaling. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 10:259–267, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J: Estimating preferences for a dermatology consultation using best-worst scaling: Comparison of various methods of analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 8:76, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy JM: Enhancing pediatric mental healthcare: Algorithms for primary care. Pediatrics 125 Suppl 3:S109–S125, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenngard AH, Hjelmgren J, Thomsen PH, Tvedten T: Patient preferences and willingness-to-pay for ADHD treatment with stimulants using discrete choice experiment (DCE) in Sweden, Denmark and Norway. Nord J Psychiatry 67:351–359, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R, Gould MS, Blanco C, Olfson M: Prescription of psychotropic medications to youths in office-based practice. Psychiatr Serv 52:1081–1087, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld WF: Marketing Research Methods in SAS: Experimental Design, Choice, Conjoint and Graphical Techniques. https://support.sas.com/techsup/technote/mr2020.pdf Accessed October30, 2012

- Leslie LK, Plemmons D, Monn AR, Palinkas LA: Investigating ADHD treatment trajectories: Listening to families' stories about medication use. J Dev Behav Pediatr 28:179–188, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A, Hodgkins P, Dewilde S, Sasane R, Falconer S, Sonuga Barke E: Methylphenidate delivery mechanisms for the treatment of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Heterogeneity in parent preferences. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 27:215–223, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louviere JJ, Flynn TN: Using best-worst scaling choice experiments to measure public perceptions and preferences for healthcare reform in Australia. Patient 3:275–283, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SE, Cho J, Ogle S, Sellman H, Dosreis S: A phenomenological case study of communication between clinicians about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder assessment. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 53:11–17, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marley AAJ, Louviere JJ: Some probabilistic models of best, worst, and best-worst choices. J Math Psychol 49:464–480, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Matza LS, Secnik K, Rentz AM, Mannix S, Sallee FR, Gilbert D, et al. : Assessment of health state utilities for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children using parent proxy report. Qual Life Res 14:735–747, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D: Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Frontiers in Econometrics. Edited by Zarembka P. New York, Academic Press, 1974, pp. 105–142 [Google Scholar]

- Muhlbacher A, Rudolph I, Lincke H-J, Nubling M: Preferences for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res 9:149, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlbacher AC, Nubling M: Analysis of patients' preferences: Direct assessment and discrete-choice experiment in therapy of adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patient 3:285–294, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nafees B, Setyawan J, Lloyd A, Ali S, Hearn S, Sasane R, et al. : Parent preferences regarding stimulant therapies for ADHD: A comparison across six European countries. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23:1189–1200, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M: Behavioral health integration: A critical component of primary care and the patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health 32:149–150, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M, Bridges JF, Ng X, Wagner LD, Frosch E, Reeves G, et al. : A best-worst scaling experiment to prioritize caregiver concerns about ADHD medication for children. Psychiatr Serv 66:208–211, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz NK, Fabiano GA, Cunningham CE, dosReis S, Waschbusch DA, Jerome S, et al. : Systematic review of patients' and parents' preferences for ADHD treatment options and processes of care. Patient 8:483–497, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secnik K, Matza LS, Cottrell S, Edgell E, Tilden D, Mannix S: Health state utilities for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on parent preferences in the United Kingdom. Med Decis Making 25:56–70, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Hironaka LK, Walter HJ, Feinberg E, Sandler J, Pellicer M, et al. : Collaborative care for children with ADHD symptoms: A randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Pediatrics 135:e858–e867, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swait J, Louviere J: The role of the scale parameter in the estimation and comparison of multinomial logit-models. J Mark Res 30:305–314, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- The MTA Cooperative Group: National Institute of Mental Health multimodal treatment study of ADHD follow-up: 24-Month outcomes of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 113:754–761, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brunt K, Matza LS, Classi PM, Johnston JA: Preferences related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence 5:33–43, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Ghandour RM, et al. : Trends in the parent-report of healthcare provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:34–46.e32, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, Cunningham CE, Pelham WE, Rimas HL, Greiner AR, Gnagy EM, et al. : A discrete choice conjoint experiment to evaluate parent preferences for treatment of young, medication naive children with ADHD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40:546–561, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M, Feldman HM, et al. : ADHD: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 128:1007–1022, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, Bickman L, Simmons T, Worley K: Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale in a referred population. J Pediatr Psychol 28:559–667, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickafoose JS, DeCamp LR, Prosser LA: Parents' preferences for enhanced access in the pediatric medical home: A discrete choice experiment. JAMA Pediatr 169:358–364, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]