Abstract

Aging diminishes bone formation engendered by mechanical loads, but the mechanism for this impairment remains unclear. Because Wnt signaling is required for optimal loading-induced bone formation, we hypothesized that aging impairs the load-induced activation of Wnt signaling. We analyzed dynamic histomorphometry of 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old C57Bl/6JN mice subjected to multiple days of tibial compression and corroborated an age-related decline in the periosteal loading response on day 5. Similarly, 1 day of loading increased periosteal and endocortical bone formation in young-adult (5-month-old) mice, but old (22-month-old) mice were unresponsive. These findings corroborated mRNA expression of genes related to bone formation and the Wnt pathway in tibias after loading. Multiple bouts (3 to 5 days) of loading upregulated bone formation–related genes, e.g., Osx and Col1a1, but older mice were significantly less responsive. Expression of Wnt negative regulators, Sost and Dkk1, was suppressed with a single day of loading in all mice, but suppression was sustained only in young-adult mice. Moreover, multiple days of loading repeatedly suppressed Sost and Dkk1 in young-adult, but not in old tibias. The age-dependent response to loading was further assessed by osteocyte staining for Sclerostin and LacZ in tibia of TOPGAL mice. After 1 day of loading, fewer osteocytes were Sclerostin-positive and, corroboratively, more osteocytes were LacZ-positive (Wnt active) in both 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice. However, although these changes were sustained after multiple days of loading in 5-month-old mice, they were not sustained in 12-month-old mice. Last, Wnt1 and Wnt7b were the most load-responsive of the 19 Wnt ligands. However, 4 hours after a single bout of loading, although their expression was upregulated threefold to 10-fold in young-adult mice, it was not altered in old mice. In conclusion, the reduced bone formation response of aged mice to loading may be due to failure to sustain Wnt activity with repeated loading.

Keywords: AGING, WNT/β-CATENIN SIGNALING, ANABOLIC, OSTEOCYTE, OSTEOBLAST

Introduction

The growing skeleton experiences a diversity of mechanical loads that modulate the accrual of bone mass and hence bone strength. However, aging brings a net decline in bone mass in part due to reduced bone formation(1–3) and can ultimately lead to osteoporosis. One factor that may contribute to diminished bone formation is an impaired ability of the aged skeleton to sense and respond to in vivo mechanical stimuli.(4–10) Understanding the mechanism of this impairment may lead to treatments to increase bone mass and reduce osteoporotic fractures.

Canonical Wnt signaling is a key anabolic pathway in bone.(11) When negative regulators secreted frizzled-related protein (SFRP), Sclerostin, or Dickkopf-related protein 1 (Dkk1) do not bind to the Wnt ligands and Lrp5 or Lrp6, respectively, Wnt ligands bind to the Lrp5/6-Frizzled receptor complex. Once activated, the tail end of the complex sequesters GSK3β and allows the stabilization of β-Catenin, which may translocate to the nucleus, interact with T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) and initiate gene transcription. The osteogenic potency of this pathway is evidenced by the fact that global and osteoblast-specific loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in LRP5 lead to osteoporotic and high-bone mass phenotypes, respectively.(12–14)

Mechanical loading, e.g., tibial compression, induces bone formation in mice,(15–17) but the response in middle-aged and old mice is less than in young-adults.(6,8–10,18) In vivo mechanical loading of ulnae in young-adult mice increases bone formation and attenuates the expression of Sost/Sclerostin.(19) Moreover, overexpression of Sost in bone cells,(20) deletion of Lrp5,(21,22) or heterozygous deletion of β-Catenin(23) disrupts the osteogenic response to mechanical stimulation in mice. Because loading-induced bone formation is both dependent on canonical Wnt signaling and is impaired with age, we hypothesized that aging diminishes the activation of Wnt signaling by mechanical loading.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design and animal model

Female C57BL/6JN inbred mice were purchased at 5, 12, and 22 months of age from the National Institute of Aging aged rodent colony (NIA, Bethesda, MD, USA), which is managed by Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). These ages correspond to young-adult, middle-aged, and old mice, respectively,(24) and we have recently shown age-related attenuation of loading-induced bone formation therein.(9) In brief, following a 1-week to 2-week acclimation period, the mice were used to determine kinetic gene expression profiles after tibial compression loading and also to demonstrate bone formation following 1 day of loading, as described in detail below in In vivo tibial compression. Samples from our previous study(9) of similarly aged C57Bl/6JN female mice were reanalyzed to assess mineralizing surface after 5 days of loading.

TOPGAL (TCF/LEF Optimal Promoter/Galactosidase reporter) transgenic mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Tg[Tcf-Lef1-lacZ]34Efu/J, stock # 004623; Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and inbred to produce experimental mice aged 5 and 12 months. The homozygous TOPGAL mice, which were maintained on a CD-1 background, were genotyped as published,(25) contain the LacZ transgene under the control of the TCF/LEF promotor,(26) and were used to assay Wnt activity in osteocytes.(27) In order to corroborate use of the TOPGAL mouse as a model of age-related attenuation of loading-induced bone formation, we determined bone formation by micro–computed tomography (μCT) and dynamic histomorphometry following 2 weeks of tibial compression (5 days/week, study days 1 to 5 and 8 to 12). Next, TOPGAL mice were mechanically loaded for either 1 or 5 days and tibias were harvested 24 hours post-loading—the time point at which sclerostin expression and β-catenin activity are most affected after loading.(27) All mice were housed 4 to 5 per cage under standard conditions with ad libitum access to water and regular chow (Purina 5053 and 5058, Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA). The animal work in this study is in compliance with all applicable agency policies and procedures. The study was approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Strain gauging

For C57Bl/6JN mice, we selected age-specific peak forces (Table 1) to generate peak periosteal strains of −2200 με at the diaphyseal site of interest (5 mm proximal of the distal tibiofibular junction) based on previous studies.(9,28) For TOPGAL mice (5 months old and 12 months old, n = 4 each), we performed strain gauge analysis using methods as described.(29) Briefly, single-element gauges (TML Tokyo Sokki Kenkyujo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; Type: FLK-1-11-1L) were adhered with cyanoacrylate to the anteromedial tibial surface, 5 mm proximal to the distal tibiofibular junction (TFJ). This site is proximal to the 50% midpoint of the tibia, but corresponds approximately to the location of peak strain along the tibial length.(28) Across a range of forces (4 to 12 N), force-strain regressions were determined. Next, each strain-gauged tibia was scanned by μCT (VivaCT 40; Scanco, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) to determine the location of the gauge relative to the neutral axis. These data were used to extrapolate from the tensile gauge site to the site of peak compressive strain (posterolateral apex) using beam theory. For TOPGAL mice, forces were determined to correspond to −650 με and −2200 με peak compressive strain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Force Values Used to Produce Target Peak Periosteal Strains in Different Mouse Groups

| Age (months) | TOPGAL

|

C57BL/6JN

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Force (N) at −650 με | Force (N) at −2200 με | Force (N) at −2200 με | |

| 5 | −4.5 | −12.5 | −8.0 |

| 12 | −4.0 | −11.25 | −7.5 |

| 22 | NA | NA | −7.0 |

NA = not applicable.

In vivo tibial compression

Mice were anesthetized (2% to 3% isoflurane) and their right tibias subjected to 1 bout/day of axial compression using a materials testing system (Electropulse 1000; Instron, Norwood, MA, USA). Each bout of loading lasted ~5 min, comprising 1200 cycles (4 Hz triangle waveform with 0.1 s rest-insertion after each cycle). This protocol is anabolic for cortical bone in young-adult and aged C57BL/6 mice.(9,16,17) Buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg s.c.) was administered after each loading session to mitigate any pain, and mice were returned to their cages where they were observed to resume unrestricted activity. The left tibia served as a non-loaded, contralateral control.

μCT

Bilateral tibias from TOPGAL mice (n = 5 to 7 in each age group) were scanned in vivo by μCT (VivaCT 40; Scanco, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) following 2 weeks of loading, immediately before euthanasia. Scan resolution was 21 μm (70 kV, 114 μm, 100 ms integration time). Cortical parameters were assessed at the diaphyseal site of interest, 5 mm proximal to the distal tibiofibular junction (TFJ), spanning 50 slices (1.1 mm). Automatic contouring was used to analyze all slices with a lower/ upper threshold of 180/1000 (330 mg hydroxyapatite [HA]/cm3, selected based on previous studies(9)) to segment bone from other tissue. The outcomes for cortical bone included bone volume (Ct.BV), total volume (Ct.TV), medullary volume (Me.V), and tissue mineral density (TMD).

Dynamic histomorphometry

First, a set of 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old C57Bl/6JN mice were subjected to 1 day of loading (n = 10 to 11 in each age group); fluorochromes were injected intraperitoneally on day 3 (calcein green, 10 mg/kg; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and day 8 (alizarin complexone, 30 mg/kg; Sigma), and mice were euthanized on day 10. Tibias were harvested and embedded undecalcified in plastic as described.(9) Dynamic histomorphometric analysis was performed on 30-μm-thick transverse sections taken at the same diaphyseal location used for strain gauge and μCT analysis (5 mm proximal to the distal TFJ). Using commercial software (Osteo II; BIOQUANT, Nashville, TN, USA), standard lamellar bone formation indices were determined: single-labeled and double-labeled surface per bone surface (sLS/BS, dLS/BS), mineralizing surface (MS/BS), mineral apposition rate (MAR), and bone formation rate (BFR/ BS).(30) Periosteal and endocortical surfaces were analyzed separately. Figure 1A illustrates an example of a loaded tibia. Next, to assess bone formation induced by multiday loading in TOPGAL mice (n = 5 to 7/age), mice were loaded days 1 to 5 and 8 to 12; fluorochromes were injected intraperitoneally on days 5 and 12, and mice were euthanized on day 15. Next, dynamic histomorphometric analysis was performed as described in the beginning of the paragraph.

Fig. 1.

(A) An example of a mid-diaphyseal section from a single-bout loaded tibia imaged by fluorescence microscopy. For dynamic histomorphometry, the entire cross-section was analyzed. The dashed square (20× magnification) highlights the posterolateral region of peak compressive strain where we determined the percentage of sclerostin-positive (Fig. 3) and Wnt-positive (Fig. 4) osteocytes. The image is from a 5-month-old loaded tibia. The solid square (40×) illustrates a higher magnification of the region. (B) Periosteal and (C) endocortical single-labeled surface (based on calcein, day 5) of 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias loaded for 5 days and control tibias. (D) Periosteal and endocortical mineralizing surface (based on calcein day 3, alizarin day 8) of 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias loaded for 1 day and control tibias. Data are represented as mean ±SD. *Loaded versus Control; Bars = 5-month-old versus 12-month-old versus 22-month-old of loaded tibias; p <0.05. Ec = endocortical; Ct = cortical; Ps = periosteal; BS = bone surface; Ps.sLS = periosteal single-labeled surface; Ps.MS = periosteal mineralizing surface; Ec.sLS = endocortical single-labeled surface; Ec.MS = endocortical mineralizing surface.

Separately, histological sections from a recent 2-week loading study of 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old C57Bl/6JN mice (n = 11 to 12/age)(9) were reanalyzed to assess mineralization after 5 days of loading. We previously reported that 12-month-old and 22-month-old mice from this study had reduced bone formation compared to 5-month-old mice based on analysis of double labels (days 5 and 12). Here we were interested in the response attributable to the first 5 days of loading and so we assessed single-labeled surface based on the day 5 calcein label (sLS/BS).

qRT-PCR

The kinetic profile of 43 genes, including Wnt pathway and bone matrix genes, was determined in C57Bl/6JN mice. One set of mice was subjected to one bout of tibial compression and tibias were harvested after 4 hours, 24 hours, or 72 hours (n = 4 to 6/age/time). A second set of mice was subjected to two to five bouts, i.e., 2 to 5 days, of tibial compression and tibias were harvested 4 hours after each bout (n = 6 to 8/age/day). At tissue harvest, the tibia was stripped of all muscle, cut at the distal TFJ, and cut to remove 2 mm of the proximal end. The tibia was briefly spun in a centrifuge to remove the bone marrow and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for short-term storage. This sample was predominantly cortical bone.

Next, the samples were pulverized in a Mikro Dismembrator (Mikro-Dismembrator S; B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany) and suspended in TRIZOL (Ambion) until further processing. Total RNA extraction was performed using a standard kit (RNeasy mini kit; Qiagen). RNA concentration was quantified (ND-1000; Nanodrop), and RNA integrity was evaluated (Bioanalyzer 2100; Agilent Technologies). Use of the sample was contingent on meeting quality standards including an appropriate absorbance ratio (260/280 nm) of 1.8 to 2.1 and electrophoretograms consistent with good quality RNA integrity numbers (RIN) ≥7. Here, the RIN mean (standard deviation) was 8.1 (0.5). First-strand cDNA was synthesized (iScript; Bio-Rad) from 500 ng of total RNA. qRT-PCR was performed using TAQMAN probes on 96 × 96 high-throughput chips on the BioMark HD System in collaboration with Genome Technology Access Center (GTAC) at Washington University in St. Louis. Based on a preliminary study, Ipo8 was selected as a reference gene. Of 16 candidate reference genes, Ipo8 had the most consistent expression with age, loading, and time following loading. The relative gene expression in each loaded tibia was represented by normalizing to Ipo8 and then normalized to the control tibia (2−ΔΔCt).

Histology

Beta-galactosidase staining for Wnt activity and immunohistochemistry for Sclerostin expression was completed on samples obtained 24 hours after 1 or 5 days of loading in 5-month-old and 12-month-old old TOPGAL mice (n = 8 to 10/group). Using a protocol developed by Dr. Mark Johnson,(27) tibias were harvested and then submerged in 4% paraformaldehyde (Alfa Aesar; 16% wt/vol aqueous solution, methanol free) for 1 hour. Next, tibias were incubated at 28°C to 32°C in X-gal solution (K3, K4, deoxycholic acid, N,N-dimethylformamide: Sigma; Mg2Cl, Tris-HCl buffer: Ambion; NP-40: Fluka; X-gal powder: Invitrogen) for 48 hours. Tibias were washed in PBS and resubmerged in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Next, tibias were decalcified in Immunodecal (Decal Chem Corp) for 48 hours, then dehydrated in increasing gradations of ethanol from 70% to 100%, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 mm proximal to the distal TFJ. Sections were counterstained with eosin for contrast. Sections for immunohistochemistry were deparaffinized and stained with biotinylated anti-mSOST (BAF 1589; R&D Systems). Counting of Wnt-active (β-gal–positive) and sclerostin-positive osteocytes was done within the posterolateral region of the tibial cross-section, where there is a robust bone formation response (Fig. 1A).

Statistical analysis

Paired Student’s t tests compared control, contralateral tibias to loaded tibias. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey tests compared ages (5 months versus 12 months versus 22 months). Statistical computations were completed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 21, Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p <0.05. In addition, correlation and clustering analyses were performed to identify genes that has similar expression patterns, as described in the Supporting Methods and Results.

Results

Older mice have diminished bone formation histologically after one or five bouts of loading

Previous studies have documented reduced bone formation in old versus young mice when subjected to loading protocols of 2 weeks’ duration.(8–10) To determine if an age-related impairment is detectable in less time, we reanalyzed a set of previously described samples from female C57Bl/6JN mice that were loaded 5 days/week for 2 weeks (fluorochrome labeled on days 5 and 12).(9) Here, we measured only the single-labeled bone surface based on the calcein label administered on day 5. The results indicated that periosteal single-labeled surface of the loaded tibia of 12-month-old and 22-month-old mice was significantly less than of 5-month-old mice (Fig. 1B); there was no age-effect for endocortical single-labeled surface (Fig. 1C). Thus, older mice had a diminished periosteal response, detectable after 5 days of loading.

To determine if the age-related impairment was evident after just a single bout of loading, we loaded another set of C57Bl/6JN mice for a single day and analyzed dynamic bone formation indices based on labels administered on days 3 and 8. On the periosteal surface, only the 5-month-old mice had a significantly detectable increase in mineralizing surface due to loading (Fig. 1D; Supporting Table 1). No differences were noted in mineralization surface of control tibias between ages. On the endocortical surface, 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice had a significant increase in mineralizing surface in loaded tibias, but again the 22-month-old mice did not show a loading effect (Fig. 1E). Collectively, the analysis of histological bone formation indicates an age-related impairment in response to one or five daily loading bouts of mechanical loading.

Older mice have diminished gene expression responses after single or multiple bouts of loading

To determine bone responses to loading at the gene transcription level, we performed qPCR on mRNA harvested from loaded and control C57Bl/6JN tibias 4 hours after either one, two, three, four, or five bouts of daily loading. After one bout of loading, expression of genes related to osteoblast differentiation (e.g., Sp7 (Osx)) and bone formation (e.g., Col1a1) was downregulated in younger mice, but not changed in older mice (Fig. 2A, B; Supporting Fig. 1). With each additional bout of loading in young-adult mice, the relative expression of these osteogenic genes increased progressively and was significantly greater in loaded versus control tibias on days 3 to 5. For example, in 5-month-old mice Col1a1 was downregulated approximately twofold by a single bout of loading, but upregulated sixfold after five loading bouts. Older mice had a significantly diminished response to loading versus young mice, with only a few instances of significant loading effects in 22-month-old mice. For Col1a1 in particular, there was no significant effect of loading after one or five bouts in 22-month-old mice. In order to rule out that lack of bone formation in the 22-month-old mice was due to a lack of a loading response rather than an increased basal expression of bone formation, we determined there was no difference in Sp7, Bglap (Ocn), Alpl, Col1a1, or Runx2 expression in the control tibias between 5-month-old, 12-month-old, or 22-month-old mice.

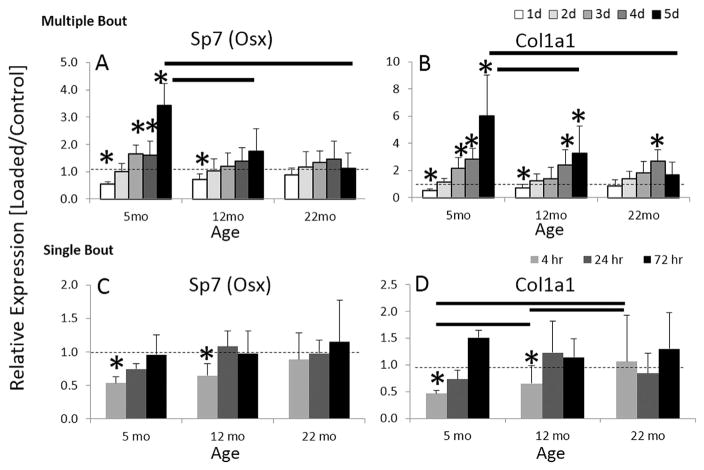

Fig. 2.

Gene expression of osteoblast differentiation marker (A) Osx and bone formation (B) Col1a1 in 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias loaded daily for up to 5 days and tibias harvested 4 hours after each day. Gene expression of (C) Osx and (D) Col1a1 in 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias loaded once and tibias harvested at 4 hours, 24 hours, and 72 hours. Data are represented as mean ± SD. *Loaded versus Control; Bars = 5-month-old versus 12-month-old versus 22-month-old; p <0.05.

To further assess the dynamics of gene expression triggered by loading, we performed qPCR on C57Bl/6JN tibias 24 hours and 72 hours after one bout of loading. In 5-month-old mice, although osteogenic expression was downregulated 4 hours after loading, it normalized by 24 or 72 hours (Fig. 2C, D; Supporting Fig. 1). In the case of Col1a1 and Sp7, relative expression was normalized at 24 hours, whereas for Alpl and Bglap it remained suppressed at 24 hours and returned to normal at 72 hours. In 22-month-old mice, a single bout of loading did not alter expression of osteoblast-related and bone formation–related genes at 4, 24, or 72 hours.

A single bout of loading downregulates Sost and Dkk1 in young and old mice, but only young mice sustain the response after multiple bouts

Downregulation of Wnt pathway antagonists Sost/Sclerostin and Dkk1 is documented in young-adult rodents within the first 24 hours after bone mechanical loading.(19,27,31) To determine if this phenomenon is affected by age, we used qPCR to evaluate Sost and Dkk1 expression in C57Bl/6JN tibias after loading. At all ages, Sost and Dkk1 were significantly downregulated 4 hours after a single bout of loading (Fig. 3A, B). In 5-month-old mice, after repeated daily loading bouts, Sost and Dkk1 were downregulated on day 3, and Sost was downregulated again on day 5. In 12-month-old mice loaded repeatedly, Dkk1 was downregulated significantly on day 3 but not at other times, whereas Sost was not affected by loading (2 to 5 days). Finally, in 22-month-old mice multiple bouts of loading (2 to 5 days) did not alter expression of either Sost or Dkk1. Thus, the early downregulation of Sost and Dkk1 after a single loading bout occurs in young and old mice, whereas only younger mice display this response after multiple loading bouts.

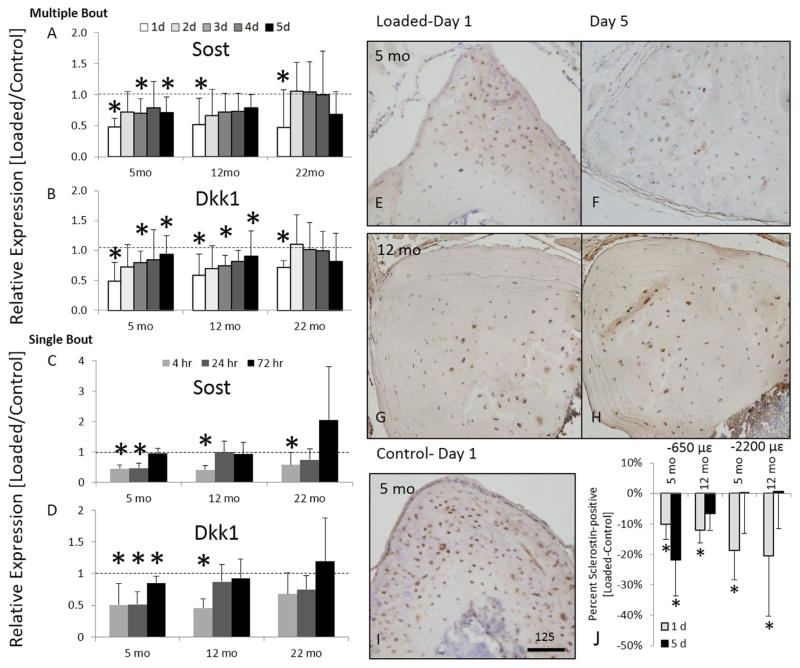

Fig. 3.

Gene expression of negative regulators of Wnt signaling (A) Sost and (B) Dkk1 in 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias loaded daily for up to 5 days and tibias harvested 4 hours after each day. Gene expression of (C) Sost and (D) Dkk1 in tibias loaded once and tibias harvested at 4 hours, 24 hours, and 72 hours. Immunohistochemistry staining for Sclerostin (brown) in 5-month-old (E, F) and 12-month-old (G, H) mice after 1 day (E, G) or 5 days of loading (F, H). (I) Control tibia of a 5-month-old animal that also exemplifies the staining of a 12-month-old control tibia. (J) Percentage of sclerostin-positive osteocytes of 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice subjected to 1 day or 5 days of tibial compression (−650 με or −2200 με). Data are represented as mean ± SD. Scale bar = 125 μm; *Loaded versus Control; p <0.05.

The kinetic profile of Sost and Dkk1 expression were also assessed in C57Bl/6JN mice 24 and 72 hours after a single bout of loading. In 5-month-old mice, Sost and Dkk1 remained down at 24 hours and returned to control levels by 72 hours (Fig. 3C, D). By contrast, expression of both Sost and Dkk1 in 12-month-old and 22-month-old mice were not different between loaded and control tibias at 24 and 72 hours. Thus, loading in younger mice suppresses Sost and Dkk1 for at least 24 hours, whereas the loading effect in older mice is more transient.

To further examine Sost/Sclerostin regulation by loading, we used immunohistochemistry (IHC) to assess the number of sclerostin-expressing osteocytes 24 hours after 1 or 5 days of loading in TOPGAL mice. (Prior to this, we confirmed using μCT and dynamic histomorphometry that bone formation was induced by mechanical loading in these mice [Supporting Fig. 2; Supporting Tables 2 and 3].) Consistent with qPCR findings, 1 day of loading caused a significant reduction in the number of sclerostin-positive osteocytes in both 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice (Fig. 3E–J). Loading for 5 days in 5-month-old mice produced mixed results, with a significant reduction at a low level of loading (−650 με), but not at a higher level (−2200 με). Loading for 5 days in 12-month-old mice did not lead to a detectable decrease in sclerostin-expressing osteocytes at either loading level. Thus, protein-level analysis mostly corroborates the mRNA results, demonstrating that young and older mice show early downregulation of sclerostin after 1 day of loading, whereas only young mice show an ability to sustain this response after 5 days of loading.

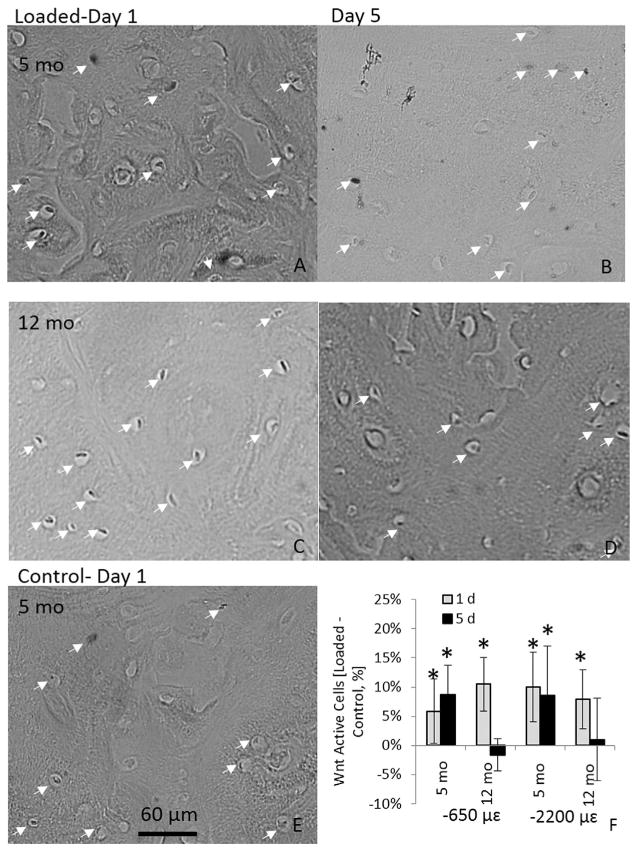

Multiple loading bouts induce sustained Wnt signaling in osteocytes of young, but not older mice

Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteocytes has been documented 24 hours after mechanical loading in TOPGAL transgenic reporter mice.(27) To assess if this response is age-and time-dependent, we loaded tibias of 5-month-old and 12-month-old TOPGAL mice for either 1 or 5 days, and assessed the number of β-galactosidase–positive (i.e., TOPGAL-expressing) osteocytes 24 hours after loading. In both 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice, there was a significant increase in TOPGAL-expressing osteocytes after 1 day of loading (at two loading levels: −650 με and −2200 με) (Fig. 4A–E). In 5-month-old mice, the increase in TOPGAL-expressing cells was also evident after 5 days of loading. By contrast, 12-month-old mice did not show increased TOPGAL expression after 5 days of loading (Fig. 4F). Thus, application of multiple loading bouts in young-adult mice produces a sustained activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteocytes, whereas multiple bouts in older mice does not.

Fig. 4.

LacZ expression (arrow) of Wnt signaling in 5-month-old (A, B) and 12-month-old (C, D) mice after 1 day (A, C) or 5 days of loading (B, D). (E) Control tibia of a 5-month-old animal that also exemplifies the staining of a 12-month-old control tibia. (F) Percentage of Wnt-positive osteocytes of 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice subjected to 1 day or 5 days of tibial compression (−650 με or −2200 με). Data are represented as mean ± SD. Scale bar = 60 μm; *Loaded versus Control; p <0.05.

Loading induces strong upregulation of Wnts 1 and 7b in an age-dependent manner

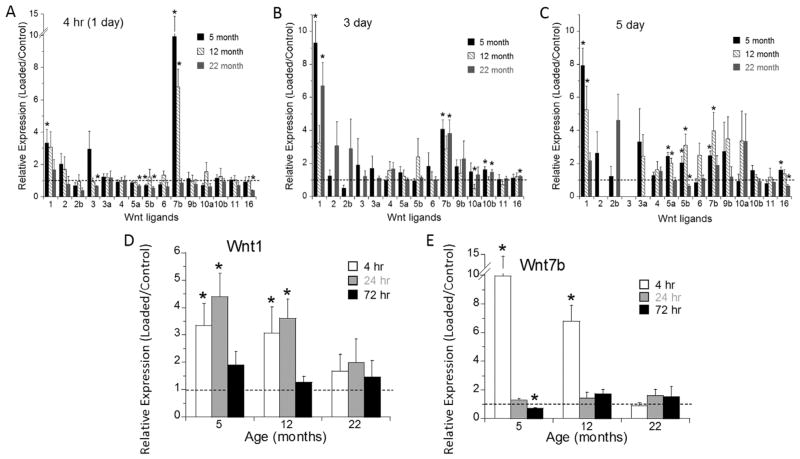

To determine if Wnt ligands are regulated by loading, we used the C57Bl/6JN samples described above to assess mRNA expression of 19 Wnts in C57Bl/6JN tibias. Four hours after a single bout of loading, there was significant upregulation of Wnts 1 (>3.0-fold) and 7b (>6.0-fold) in both 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice, although not in 22-month-old mice (Fig. 5A, Supporting Table 6). No other Wnt ligands were significantly upregulated at this time point, whereas several were modestly downregulated. After 3 days of loading, Wnts 1 (>9.0-fold) and 7b (>4.0-fold) were again upregulated in 5-month-old mice (Fig. 5B). At this time point, these ligands were not significantly upregulated in 12-month-old mice, although they were up in 22-month-old mice. Several additional ligands were differently expressed at 3 days, although by less than twofold. Finally, 5 days of loading caused upregulation of Wnt 1 (>5.0-fold) and 7b (>2.0-fold) in 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice, but not in 22-month-old mice (Fig. 5C). At this time point, Wnts 5a and 5b were also up (twofold to threefold) with loading in the younger mice. In summary, loading caused strong upregulation of Wnts 1 and 7b in an age-dependent manner, with younger mice showing the most consistent response (i.e., up on days 1, 3, and 5).

Fig. 5.

Gene expression of 19 Wnt ligands in 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias loaded for (A) 1 day, (B) 3 days, or (C) 5 days and tibias harvested 4 hours after the last day of loading. Gene expression of (D) Wnt1 and (E) Wnt7b in 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias harvested 4, 24, or 72 hours after a single day of loading. Data are represented as mean ± SD. *Loaded versus Control; p <0.05.

To further examine the dynamics of expression of Wnts 1 and 7b, we performed qPCR on the C57Bl/6JN tibial samples collected 24 and 72 hours after a single bout of loading. The upregulation of Wnt1 in 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice observed at 4 hours was maintained at 24 hours, and returned to normal at 72 hours (Fig. 5D). In contrast, the strong upregulation of Wnt7b observed at 4 hours did not persist at 24 or 72 hours (Fig. 5E).

Additional Wnt-related gene expression

Examination of expression of several Wnt-related genes provides some additional support for the view that the pathway was activated by loading in an age-dependent manner, although the evidence was mixed. The Wnt ligand antagonist Sfrp1 showed a pattern of expression similar to osteogenic genes like Col1a1; i.e., a single loading bout induced downregulation at 4 hours followed by normalization at 24 hours, while three to five loading bouts produced potent upregulation in 5-month-old mice but less so in older mice (Supporting Tables 4 and 5). This contrasts the expression profile of the negative regulators Sost and Dkk1, which were downregulated consistently in younger mice and were never upregulated. The Wnt co-receptors Lrp5 and 6 were modestly downregulated (0.5-fold to 0.7-fold) 4 hours after a single bout of loading in 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice but were upregulated (1.4-fold to 1.7-fold) at this time point in 22-month-old mice. Lrp5 and Lrp6 were essentially unchanged after multiple bouts of loading (maximal change 1.3-fold upregulation). Loading did not strongly alter expression of genes related to Wnt intracellular signaling. Beta-catenin (Ctnnb1) was only modestly regulated by loading (<1.5-fold changed), although it showed a trend to increase with progressive loading bouts in 5-month-old mice, which would favor activation of the pathway. Gsk3b showed no evidence of differential expression with loading. Last, we assayed genes reported to be Wnt targets—Axin2, Ccnd1, Lef1, and Tnfrsf11b (Opg). Ccnd1 showed only modest, inconsistent changes in expression after a single bout of loading, but was progressively upregulated after multiple loading bouts, especially in younger mice. Similarly, Tnfrsf11b (Opg) was not altered by a single bout of loading, but was upregulated approximately 1.7-fold after 3 to 4 days of loading in young mice. Although the increases in Ccnd1 and Tnfrsf11b (Opg) were modest (<2.0-fold), they are consistent with activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. Neither Lef1 nor Axin2 were upregulated by loading, suggesting that they may not be transcriptional targets of loading-induced Wnt signaling in bone.

Adipogenic gene expression

Stimuli that are pro-osteogenic are generally held to be anti-adipogenic. Wnt signaling may be involved in this reciprocal regulation, as canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling via Wnt10b is anti-adipogenic,(32,33) whereas noncanonical Wnt signaling via Wnt11 is pro-adipogenic.(34) We assayed mRNA levels of key adipogenic factors Pparg and Cebpa in loaded and control bones from C57Bl/6JN mice. A single bout of loading suppressed expression (0.5-fold to 0.7-fold) of both Pparg and Cebpa at 4 hours, 24 hours, and 72 hours in 5-month-old mice, but not in older mice (Supporting Table 5). Modest suppression of these genes was also seen at several time points after multiple bouts of loading, although effect sizes were small (0.7-fold to 0.8-fold; Supporting Table 4). Loading did not cause upregulation of either Pparg or Cebpa (except for a small [1.3-fold] increase in 22-month-old mice after 5 days of loading). Thus, loading tended to be modestly anti-adipogenic. Interestingly, two ligands reported to be important regulators of adipogenesis, Wnts 10b and 11, were generally not regulated by loading, suggesting that any anti-adipogenic effects of loading may not be Wnt-mediated.

Discussion

With aging, there is reduced responsiveness of the skeleton to physical loading.(35,36) Weight-bearing exercise that is beneficial to bone in premenopausal women(37,38) is typically not effective in elderly women.(39,40) In animals, the anabolic effects of direct skeletal loading are greater in growing or young-adult animals compared to older animals.(4–6,8–10,17,18) To clarify why the skeleton has diminished mechanoresponsiveness with aging, we applied axial compression to the tibias of young-adult (5-month-old), middle-aged (12-month-old), and old (22-month-old) C57Bl/6JN female mice at forces that produce equivalent peak strains; we characterized early histologic and gene expression changes. We find that tissue-level indices of bone formation are diminished with age for loading protocols as brief as 1 and 5 days, similar to past studies that were 2 to 6 weeks in duration.(8–10,17,18) Similarly, at the transcriptional level, 3 to 5 days of loading produces a smaller upregulation of bone formation–related genes (e.g., Col1a1) in old mice than in young-adult mice. Regarding the Wnt pathway, repeated loading bouts fail to elicit the prototypical downregulation of the negative regulator Sost in old C57Bl/6JN mice, whereas repeated loading fails to sustain activation of osteocytic Wnt signaling in middle-aged TOPGAL mice. Finally, loading induces an early and sustained upregulation of Wnt1 and 7b in bones of young-adult mice, but this response is muted in older mice. Together, these findings support our hypothesis that aging impairs the activation of Wnt signaling by mechanical loading, consistent with an attenuated bone formation response.

Results of numerous animal studies support the consensus that the aged skeleton is less mechanoresponsive than the young-adult skeleton.(7) Early studies of direct skeletal loading in turkeys(4) and rats(5) found negligible responses in older animals to loading protocols that increased bone mass or the rate of bone formation in younger animals. Later studies in mice have shown that old mice are mechanoresponsive, albeit at a significantly diminished level compared to young-adult mice.(6,8–10,18,41) Recently, in C57Bl/6JN female mice, using a loading protocol identical to the one used in the current study, we established that tibial compression leads to a periosteal bone formation response that is reduced by ~50% in old mice compared to young-adult mice.(9) The current study extends these previous findings, which have primarily used tissue-level outcomes such as bone area and bone formation rate, by describing how age affects gene expression and the Wnt signaling responses to loading.

Indirect evidence has implicated altered cell proliferation(8) and Wnt signaling(41) as mechanisms for the age-related decline in bone mechanoresponsiveness. Meakin and colleagues(8) reported that osteoblasts from old mice were less proliferative after in vitro stretching, and also that tibial compression in old mice produced a lesser increase in periosteal osteoblast number than in young mice. They concluded that aging impairs the proliferative response of osteoblasts to loading, although in vivo proliferation was not assessed. Because Wnt signaling is important for osteoblast proliferation,(42) these results are consistent with a model whereby loading in old mice fails to induce a strong Wnt signaling response which in turn leads to a muted osteoblast proliferative response and less bone formation. But in apparent contradiction, they also reported that 24 hours after a single bout of loading, the reduction in the number of sclerostin-positive osteocytes was equal in old and young mice, suggesting no impairment in activation of Wnt signaling.(8) However, our findings indicate that examination of Sost/Sclerostin levels after a single bout of loading fails to discern the age effect, as mice at all ages had comparable downregulation 4 hours (Sost) and 24 hours (Sclerostin) after a single loading bout (Fig. 3). Importantly, in young mice the downregulation responses are sustained (or repeated) after multiple bouts, whereas in older mice they are not. Moreover, older TOPGAL mice fail to show evidence of sustained Wnt activation in osteocytes after repeated bouts of loading (Fig. 4). Thus, impairment of loading-induced Wnt signaling in older mice may contribute to a reduced osteoblast proliferative response. Srinivasan and colleagues(41) used low-dose cyclosporine A to rescue the response of aged mice to tibial loading, and hypothesized that this was through activation of the Ca2+/ NFAT signaling pathway in part via inhibition of Gsk3β. This is consistent with cyclosporine A boosting the activation of Wnt signaling by loading in old mice, although data in support of this mechanism were not presented. Taken together, our results are consistent with the model proposed by Srinivasan and colleagues(41) that aging impairs activation of mechanotransduction pathways, and extends their model by implicating Wnt signaling as a downstream pathway whose activation is aging-impaired.

The importance of the Wnt signaling pathway in loading-induced bone formation is well known.(43) Mechanical loading in young-adult animals induces downregulation of Sost/Sclerostin at sites of subsequent bone formation(19,44) and stimulates canonical Wnt signaling.(27,45) Moreover, the osteogenic response to loading in mice is disrupted by overexpression of Sost in bone cells,(20) deletion of Lrp5(21,22) or heterozygous deletion of β-catenin.(23) Our study extends these previous findings by documenting the changes in expression of Wnt ligands after loading, and finding strong induction of Wnt1 and Wnt7b by single and multiple bouts of tibial loading in young-adult mice (Fig. 5). Old mice had a mixed response, with no upregulation of Wnt1 and Wnt7b after one or five bouts, but upregulation after three bouts. Interestingly, the early (4 hours) upregulation of Wnt1 after a single bout of loading in 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice was sustained for 24 hours before returning to normal at 72 hours (Fig. 5D), whereas the upregulation of Wnt7b was seen only at 4 hours (Fig. 5E). These findings are consistent with Kelly and colleagues,(46) who performed RNA-Seq on tibias of 10-week-old mice after one bout of tibial compression. They reported increased Wnt1 expression in cortical bone at 3 hours (6.2-fold) and 24 hours (6.1-fold) after loading, and increased Wnt7b (3.2-fold) at 3 hours. Collectively, these results demonstrate that upregulation of Wnt1 and Wnt7b is an early response to bone loading. These findings are notable in light of recent genetic evidence for a critical anabolic role of Wnt 1(47,48) and Wnt 7b(49) in the postnatal skeleton.

Our findings differ from previous reports in several regards. First, we did not find a significant change in Wnt10b expression after one bout of loading, whereas others have reported increased Wnt10b at 3 to 4 hours and 24 hours after loading.(45,46) One possible reason for the difference is that we used a less stimulating protocol. We applied 7 to 8 N peak force to engender −2200 με peak compressive strain at the diaphyseal site of interest, a protocol we have shown stimulates lamellar bone formation with little to no woven bone.(9) Kelly and colleagues(46) applied a slightly higher peak force (9 N) using an otherwise identical protocol, whereas Robinson and colleagues(45) used a tibial four-point bending protocol that has been shown to induce woven bone.(50) Another finding at odds with some previous reports is the downregulation of osteoblast/bone formation genes early after initial loading. Specifically, we observed that Alpl, Bglap, Col1a1, Runx2, and Sp7 were 30% to 60% reduced 4 hours after a single bout of loading in 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice, whereas after 3 to 5 days of loading each of these genes was upregulated, consistent with the timing of bone formation (Figs. 1 and 2). Mantila Roosa and colleagues(51) likewise noted upregulation of Col1a1 after 4 days of ulnar loading in rats, but did not find altered expression 4 hours after one loading bout. Furthermore, Kelly and colleagues(46) did not report downregulation of osteogenic genes at the 3-hour time point, despite several consistent findings with our study (i.e., early upregulation of Wnt1 and Wnt7b and downregulation of Sost and Dkk1). On the other hand, Raab-Cullen and colleagues(52) reported decreased expression of Alp, Ocn, and Opn 4 hours after rat tibial bending, and we noted a downregulation of osteogenic genes in 6-month-old male C57Bl/6 mice, 4 hours after 60 cycles of tibial compression.(31) Finally, microarray data from Zaman and colleagues(53) indicate downregulation of Col1a2 and Bglap2 at 8 hours after tibial compression in C57Bl/6 mice. The significance of early downregulation in bone genes is unclear, but this phenomenon is consistent with a phenotypic suppression phenomenon mediated by AP-1(54) that does not impede eventual bone formation.

There a several limitations that must be discussed. First, our study was limited to female mice. We chose to focus our efforts on one gender, and selected female mice in part to avoid the need for individual housing; male mice housed as a group engage in fighting that can limit load-induced bone formation.(55) However, we cannot be certain that the age-related impairment of Wnt activation by mechanical loading that we observed in female mice would also occur in male mice. Female and male C57Bl/6 mice exhibit a similar amount and pattern of age-related cortical bone loss; in both sexes, aged mice lose bone due to marrow expansion and cortical thinning.(8) Moreover, in males and females, tibial loading induces less cortical bone accrual in aged versus young-adult mice, and in both sexes this is due to impaired periosteal apposition.(8) Thus, there is reason to hypothesize that our results also apply to male mice. Second, the histological data demonstrating load-induced Wnt signaling activation in TOPGAL mice and reduced sclerostin expression are based on a subjective, binary grading of individual cells. It is possible that Western blotting could provide a less subjective assessment of protein levels of TCF/LEF or sclerostin. Nonetheless, the findings of the histological analysis were consistent with qPCR data and are complementary because they are based on osteocytes alone. Moreover, the Wnt-reporter TOPGAL mouse is a well-regarded method for demonstrating activation of the canonical pathway; it relies on β-catenin functionally binding to the TCF/LEF motifs and transcription of the LacZ transgene. Last, our current approach at determining the gene expression of the tibias was harvesting the cortical bone of the whole midshaft and extracting RNA from the homogenate. There is the possibility that the gene expression of the osteoblasts on and the osteocytes near the periosteal and endosteal surfaces may have differed. Future studies are needed to unravel potential surface-dependent differences in response to mechanical loading.

In summary, old mice subjected to tibial compression have a diminished early bone formation response and fewer differentially expressed genes compared to young mice (Fig. 6A). Further, the number of significant correlations between gene pairs decreases as a function of age and there are fewer similar correlations between 22-month-old animals and younger mice than there are between 5-month-old and 12-month-old mice (Fig. 6B). Using downregulation of Sost/Sclerostin and activation of Wnt reporter expression (TOPGAL) in osteocytes as indicators of Wnt pathway regulation, we find that old mice have a normal Wnt response after a single loading bout, but appear to be unable to respond to repeated bouts. Finally, early upregulation of Wnt1 and 7b after a single bout of loading is a notable feature of the response of bone to mechanical loading and is also muted with aging. In conclusion, the reduced bone anabolic response to loading in old mice includes a failure to sustain Wnt activity with repeated loading bouts.

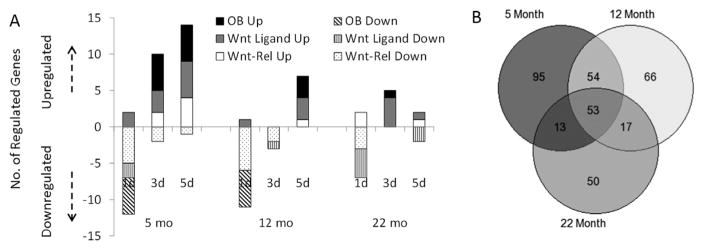

Fig. 6.

(A) Compilation of the number of osteoblast (OB; black bar), Wnt ligand (gray), and Wnt-related (Wnt-Rel; white) genes regulated by 1, 3, or 5 days of loading in 5-month-old, 12-month-old, and 22-month-old tibias, where the solid bars denote upregulation and the patterned bars denote downregulation. Overall, aging reduced the response of bone formation–related genes to multiple days of loading. (B) Venn diagram depicting the number of significant correlations between gene pairs as a function of age. Of the 780 possible gene-pairs analyzed, there were 216, 190, and 133 significant correlations at 5 months, 12 months, and 22 months, respectively; 53 of these were common to all ages (See Supplemental Methods and Results for details of correlation analyses.). OB = osteoblast.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AR047867 (MJS) and F32 AR064667 (NH), by the Washington University Musculoskeletal Research Center (P30 AR057235, T32 AR060719), and by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (UL1TR000448). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. We gratefully acknowledge Michelle Sanchez, Bronwyn Bedrick, Rhiannon Aguilar, and Bradley Bomar, who each contributed to data collection during the study.

Authors’ roles: Study Design: NH and MS. Data Acquisition: NH and MB. Data analysis: NH, MB, MS. Data interpretation: NH, MB, MS. Drafting manuscript: NH and MS. NH and MS take responsibility for integrity of manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Lips P, Courpron P, Meunier PJ. Mean wall thickness of trabecular bone packets in the human iliac crest: changes with age. Calcif Tissue Res. 1978;26:13–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02013227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parfitt AM, Villanueva AR, Foldes J, Rao DS. Relations between histologic indices of bone formation: implications for the pathogenesis of spinal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10(3):466–73. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson VL, Ayers RA, Bateman TA, Simske SJ. Bone development and age-related bone loss in male C57BL/6J mice. Bone. 2003;33(3):387–98. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin CT, Bain SD, McCleod KJ. Suppression of osteogenic response in the aging skeleton. Calcif Tissue Int. 1992;50(4):306–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00301627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner CH, Takano Y, Owan I. Aging changes mechanical loading thresholds for bone formation in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10(10):1544–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivasan S, Agans SC, King KA, Moy NY, Poliachik SL, Gross TS. Enabling bone formation in the aged skeleton via rest-inserted mechanical loading. Bone. 2003;33(6):946–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotiya AA, Silva MJ. The effect of aging on skeletal mechanoresponsiveness: animal studies. In: Silva MJ, editor. Skeletal aging and osteoporosis: biomechanics and mechanobiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2013. pp. 191–216. Studies in Mechanobiology, Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meakin LB, Galea GL, Sugiyama T, Lanyon LE, Price JS. Age-related impairment of bones’ adaptive response to loading in mice is associated with sex-related deficiencies in osteoblasts but no change in osteocytes. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(8):1859–71. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holguin N, Brodt MD, Sanchez ME, Silva MJ. Aging diminishes lamellar and woven bone formation induced by tibial compression in adult C57BL/6. Bone. 2014;65:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razi H, Birkhold AI, Weinkamer R, Duda GN, Willie BM, Checa S. Aging leads to a dysregulation in mechanically driven bone formation and resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(10):1864–73. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19(2):179–92. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, et al. LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 2001;107(4):513–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyden LM, Mao J, Belsky J, et al. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein 5. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(20):1513–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui Y, Niziolek PJ, MacDonald BT, et al. Lrp5 functions in bone to regulate bone mass. Nat Med. 2011;17(6):684–91. doi: 10.1038/nm.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiyama T, Meakin LB, Browne WJ, Galea GL, Price JS, Lanyon LE. Bones’ adaptive response to mechanical loading is essentially linear between the low strains associated with disuse and the high strains associated with the lamellar/woven bone transition. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(8):1784–93. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holguin N, Brodt MD, Sanchez ME, Kotiya AA, Silva MJ. Adaptation of tibial structure and strength to axial compression depends on loading history in both C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93(3):211–21. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9744-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch ME, Main RP, Xu Q, et al. Tibial compression is anabolic in the adult mouse skeleton despite reduced responsiveness with aging. Bone. 2011;49(3):439–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva MJ, Brodt MD, Lynch MA, Stephens AL, Wood DJ, Civitelli R. Tibial loading increases osteogenic gene expression and cortical bone volume in mature and middle-aged mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robling AG, Niziolek PJ, Baldridge LA, et al. Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of Sost/sclerostin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(9):5866–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tu X, Rhee Y, Condon KW, et al. Sost downregulation and local Wnt signaling are required for the osteogenic response to mechanical loading. Bone. 2012;50(1):209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawakami K, Robling AG, Ai M, et al. The Wnt co-receptor LRP5 is essential for skeletal mechanotransduction but not for the anabolic bone response to parathyroid hormone treatment. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(33):23698–711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao L, Shim JW, Dodge TR, Robling AG, Yokota H. Inactivation of Lrp5 in osteocytes reduces young’s modulus and responsiveness to the mechanical loading. Bone. 2013;54(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Javaheri B, Stern AR, Lara N, et al. Deletion of a single beta-catenin allele in osteocytes abolishes the bone anabolic response to loading. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(3):705–15. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flurkey K, Currer JM, Harrison DE. Mouse models in aging research. In: Fox JG, Barthold SW, Davisson MT, Newcomer CE, Quimby FW, Smith AL, editors. The mouse in biomedical research. 2. Vol. 3. Burlington: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 637–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holguin N, Aguilar R, Harland RA, Bomar BA, Silva MJ. The aging mouse partially models the aging human spine: lumbar and coccygeal disc height, composition, mechanical properties, and Wnt signaling in young and old mice. J Appl Physiol. 2014;116(12):1551–60. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01322.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126(20):4557–68. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lara-Castillo N, Kim-Weroha NA, Kamel MA, et al. In vivo mechanical loading rapidly activates beta-catenin signaling in osteocytes through a prostaglandin mediated mechanism. Bone. 2015;76:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel TK, Brodt MD, Silva MJ. Experimental and finite element analysis of strains induced by axial tibial compression in young-adult and old female C57Bl/6 mice. J Biomech. 2014;47(2):451–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brodt MD, Silva MJ. Aged mice have enhanced endocortical response and normal periosteal response compared to young-adult mice following 1 week of axial tibial compression. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(9):2006–15. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(1):2–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kotiya AA, Bayly PV, Silva MJ. Short-term low-strain vibration enhances chemo-transport yet does not stimulate osteogenic gene expression or cortical bone formation in adult mice. Bone. 2011;48(3):468–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett CN, Ross SE, Longo KA, et al. Regulation of Wnt signaling during adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(34):30998–1004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science. 2000;289(5481):950–3. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keats EC, Dominguez JM, 2nd, Grant MB, Khan ZA. Switch from canonical to noncanonical Wnt signaling mediates high glucose-induced adipogenesis. Stem Cells. 2014;32(6):1649–60. doi: 10.1002/stem.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohrt WM, Villalon KL, Barry DW. Effects of exercise and physical interventions on bone: clinical studies. In: Silva MJ, editor. Skeletal aging and osteoporosis: biomechanics and mechanobiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2012. pp. 235–56. Studies in Mechanobiology, Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srinivasan S, Gross TS, Bain SD. Bone mechanotransduction may require augmentation in order to strengthen the senescent skeleton. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11(3):353–60. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vainionpaa A, Korpelainen R, Sievanen H, Vihriala E, Leppaluoto J, Jamsa T. Effect of impact exercise and its intensity on bone geometry at weight-bearing tibia and femur. Bone. 2007;40(3):604–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winters-Stone KM, Snow CM. Site-specific response of bone to exercise in premenopausal women. Bone. 2006;39(6):1203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck BR, Snow CM. Bone health across the lifespan—exercising our options. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003;31(3):117–22. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korpelainen R, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Heikkinen J, Vaananen K, Korpelainen J. Effect of impact exercise on bone mineral density in elderly women with low BMD: a population-based randomized controlled 30-month intervention. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(1):109–18. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1924-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srinivasan S, Ausk BJ, Prasad J, et al. Rescuing loading induced bone formation at senescence. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010 Sep 9;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan SH, Senarath-Yapa K, Chung MT, Longaker MT, Wu JY, Nusse R. Wnts produced by Osterix-expressing osteolineage cells regulate their proliferation and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(49):E5262–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420463111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonewald LF, Johnson ML. Osteocytes, mechanosensing and Wnt signaling. Bone. 2008;42(4):606–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.12.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moustafa A, Sugiyama T, Prasad J, et al. Mechanical loading-related changes in osteocyte sclerostin expression in mice are more closely associated with the subsequent osteogenic response than the peak strains engendered. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(4):1225–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1656-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson JA, Chatterjee-Kishore M, Yaworsky PJ, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a normal physiological response to mechanical loading in bone. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(42):31720–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly NH, Schimenti JC, Ross FP, van der Meulen MC. Transcriptional profiling of cortical versus cancellous bone from mechanically-loaded murine tibiae reveals differential gene expression. Bone. 2016 May;86:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joeng KS, Lee YC, Jiang MM, et al. The swaying mouse as a model of osteogenesis imperfecta caused by WNT1 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(15):4035–42. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laine CM, Joeng KS, Campeau PM, et al. WNT1 mutations in early-onset osteoporosis and osteogenesis imperfecta. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(19):1809–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J, Tu X, Esen E, et al. WNT7B promotes bone formation in part through mTORC1. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akhter MP, Cullen DM, Recker RR. Bone adaptation response to sham and bending stimuli in mice. J Clin Densitom. 2002;5(2):207–16. doi: 10.1385/jcd:5:2:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mantila Roosa SM, Liu Y, Turner CH. Gene expression patterns in bone following mechanical loading. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(1):100–12. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raab-Cullen DM, Thiede MA, Petersen DN, Kimmel DB, Recker RR. Mechanical loading stimulates rapid changes in periosteal gene expression. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994;55(6):473–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00298562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zaman G, Saxon LK, Sunters A, et al. Loading-related regulation of gene expression in bone in the contexts of estrogen deficiency, lack of estrogen receptor alpha and disuse. Bone. 2010;46(3):628–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lian JB, Stein GS, Bortell R, Owen TA. Phenotype suppression: a postulated molecular mechanism for mediating the relationship of proliferation and differentiation by Fos/Jun interactions at AP-1 sites in steroid responsive promoter elements of tissue-specific genes. J Cell Biochem. 1991;45(1):9–14. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240450106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meakin LB, Sugiyama T, Galea GL, Browne WJ, Lanyon LE, Price JS. Male mice housed in groups engage in frequent fighting and show a lower response to additional bone loading than females or individually housed males that do not fight. Bone. 2013;54(1):113–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.