Abstract

Background The low-profile dorsal locking plating (DLP) technique is useful for treating dorsally comminuted intra-articular distal radius fractures; however, due to the complications associated with DLP, the technique is not widely used.

Methods A retrospective review of 24 consecutive cases treated with DLP were done.

Results All cases were classified into two types by surgical strategy according to the fracture pattern. In type 1, there is a volar fracture line distal to the watershed line in the dorsally displaced fragment, and this type is treated by H-framed DLP. In type 2, the displaced dorsal die-punch fragment is associated with a minimally displaced styloid shearing fracture or a transverse volar fracture line. We found that the die-punch fragment was reduced by the buttress effect of small l-shaped DLP after stabilization of the styloid shearing for the volar segment by cannulated screws from radial styloid processes. At 6 months after surgery, outcomes were good or excellent based on the modified Mayo wrist scores with no serious complications except one case. The mean range of motion of each type was as follows: the palmar flexion was 50, 65 degrees, dorsiflexion was 70, 75 degrees, supination was 85, 85 degrees, and pronation was 80, 80 degrees; in type 1 and 2, respectively.

Conclusion DLP is a useful technique for the treatment of selected cases of dorsally displaced, comminuted intra-articular fractures of the distal radius with careful soft tissue coverage.

Keywords: dorsally displaced distal radius fractures, low-profile dorsal locking plates, surgical strategy and technique, fracture type, indication and clinical results

Most fractures of the distal radius can be treated with volar locking plates (VLPs) including the majority (89.6%) of AO C3-type fractures.1 VLP has recently gained widespread acceptance as the primary option for the treatment of this trauma.2 However, dorsally displaced fractures accompanied by the following conditions are not easy to treat using a single VLP3 4: when a significant dorsal die-punch is present, which sometimes involves the displacement of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ); or when a volar fracture line is distal to the watershed line or associated with dorsal communicated fractures. In these situations, the ulnar corner fragment occasionally cannot be held by a VLP or the distal edge of VLP can impinge on flexor tendons and cause injury. The displaced dorsal wall is involved with an elevated large roof, a rotated rim fragment, or impaction of the articular surface, which may cause arthritis of the wrist, or irritation of extensor tendon. These displacements seemed to be difficult to correct by a single volar approach.

Although dorsal plating has an advantage for reduction and fixation of the dorsally displaced fracture, surgeons have trended away from using dorsal fixation of distal radius fractures due to historically higher complication rates, including extensor tendon complications.3 5 6 However, a new generation of 1.0- to 1.6-mm, low-profile dorsal locking plates (DLPs) have been designed to minimize tendon irritation.7 8 9 10

Here, we retrospectively reviewed on patients treated by DLPs. The purpose of this study was to demonstrate our surgical strategy and technique of DLPs for displaced distal radius fractures according to the fracture patterns. We showed our DLP techniques based on fracture patterns to obtain accurate correction and rigid fixation and avoid extensor tendon irritations, using our original dorsal soft tissue coverage.

Materials and Methods

Patients

A total of 276 cases who underwent distal radius fracture surgery over the last 6 years (2009–2015) were followed up for more than 6 months at three major trauma institutions. Among them, 197 cases were treated using locking plates and the others were treated using percutaneous Kirschner wires (K-wire), cannulated screws, or bridging or nonbridging external fixators. VLP was necessary in 173 cases and DLP was selected in 24 cases, accounting for 12% of all cases using locking plates. The mean age and male-to-female ratio of each group were 48 years (range, 19–70 years) and 1:0.85 in DLP and 65 years (range, 26–83 years) and 1:3 in VLP, respectively. The patients treated using DLP were significantly younger (p < 0.05) than those treated using VLP. A total of 24 patients were followed up for a minimum of 6 months, and the mean follow-up time was 39 months (range, 6–74 months). X-rays (including posteroanterior, oblique, lateral, and 10 degrees tilt lateral views) were examined before, during, and after surgery. All cases were examined using three-dimensional computed tomography before surgery.

Patients were divided into two groups according to the fracture pattern (types 1 and 2 as shown in Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2) as follows.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

| Age (y) | Gender | High energy | MMWS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | ||||

| 1 | 46 | M | Fall | E |

| 2 | 66 | F | – | G |

| 3 | 45 | M | Fall | E |

| 4 | 60 | F | Fall | G |

| 5 | 49 | M | Fall | E |

| 6 | 68 | F | – | G |

| 7 | 55 | F | Fall | E |

| 8 | 54 | M | – | E |

| 9 | 70 | F | – | G |

| Mean | 57 | |||

| Type 2 | ||||

| 1 | 53 | F | Fall | E |

| 2 | 19 | M | Motorcycle | E |

| 3 | 63 | F | – | G |

| 4 | 48 | F | Fall | E |

| 5 | 23 | M | Motorcycle | E |

| 6 | 66 | M | – | F |

| 7 | 21 | M | Motorcycle | E |

| 8 | 70 | F | – | G |

| 9 | 21 | M | Motorcycle | E |

| 10 | 42 | M | – | E |

| 11 | 47 | M | – | E |

| 12 | 20 | M | Motorcycle | E |

| 13 | 51 | F | – | G |

| 14 | 23 | M | Fall | E |

| 15 | 70 | F | – | G |

| Mean | 42 | |||

Abbreviations: –, represents low energy (fall down); E, excellent; F, fair; G, good; MMWS, modified Mayo wrist score.

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the type 1 fracture. This dorsal transition of both radial and ulnar columns is caused by dorsal shearing force and compression force, and is classified as follows. (A) A dorsal Barton fracture with no volar fracture line was observed in one case. The dorsal transition type of that volar fracture line is distal to the watershed line and is often accompanied by (B) central depression of the joint surface (three cases) or (C) the dorsal roof and rim fragments (five cases), which creates instability. RC, radial column; UC, ulnar column.

Fig. 2.

Schematic drawing of the type 2 fracture. This type includes the DUC (dorsal die-punch) fragment in all 15 cases, accompanied by a minimally displaced SSF (in 13 cases) or TVFL (in 6 cases). DUC, dorsoulnar column; SSF, styloid shearing fragment; TVFL, transverse volar fracture line.

In type 1 (Fig. 1), the dorsal transition type which involves or distal to the watershed line. This type is often accompanied by a displaced dorsal roof and rim fragments or central depression of the articular surface. This type was observed in nine cases and treated using H-framed DLP, which can internally fix the dorsal displaced involving both in the dorsal ulnar columns (DUC) and radial columns (RC).

Type 2 includes the DUC which was often accompanying with minimally displaced RC which can be treated percutaneous correction and fixation (Fig. 2). All 15 cases included the dorsal die-punch fragment, which was accompanied by minimally displaced styloid shearing fracture (SSF) in 13 cases or transverse volar fracture lines (TVFL) with little displacement in six cases. In this type, we used small l-shaped DLP to reduce the displaced dorsal die-punch fragment by its buttress effect proximally to distally using a limited DUC opening approach after stabilizing the minimally displaced SSF or TVFL using cannulated screws from the tip of the radial styloid through a small incision. The classification between type 1 and 2 was done according to the surgical strategy, therefore, if the minimally displaced RC could be reduced manually or using percutaneous K-wire and fixed by a screw, these cases were classified as type 2.

We described the preparation of extensor retinaculum and periosteum to avoid direct contact between plate and extensor tendon especially at the distal half of the DLP up to the wound closure (Fig. 3). We always prepared four flaps for the dorsal approach, which makes coverage of dorsal plate stable.

Fig. 3.

A dorsal approach to soft tissue treatment before and after dorsal plating. We devised procedures to prepare and close the extensor retinaculum and periosteum to avoid direct contact between the plate and extensor tendon, especially at the distal half of the DLP as shown. The reliable and stable closure was made by making the following four flaps (a, b, c, and p). (A) A longitudinal incision was made 5 to 10 mm ulnar to the Lister tubercle in the distal radius region. Dissection was performed down to the extensor retinaculum. The fourth compartment was opened by cutting the extensor retinaculum in a zig-zag fashion to make three flaps (a, b, and c). (B) The EDC was displaced radially and the gliding floor of fourth compartment and fifth compartment wrist extensors (zone-1; ulnar side) were subperiosteally elevated ulnarly. If radial column exposure is necessary for the treatment of type 1 fracture, the retinaculum of the third or second extensor compartment is opened, elevating the EPL. The third or second compartment (zone-2; radial side) is subperiosteally elevated radially for dorsal plating. The dorsal interosseous nerve may be cutoff for pain reduction. (C and D) Our devised points at the time of wound closure include steps as follows. Removal of tuberculum listeri is rarely necessary. The previously separated flaps of the extensor retinaculum (a, c) were sutured to the ulnar side of the periosteal flap to cover the distal half of the plate. The distal half of the dorsal plate where soft tissue coverage is important to prevent tendon irritation. (E) Another flap of the extensor retinaculum (b) was repaired adjacent to the radiocarpal joint level to prevent the bowstring of extensor tendons. EPL can be used on the outside of extensor retinaculum. The incision is closed. DLP, dorsal locking plating; EDC, extensor digitorum communis; EPL, extensor pollicis longus.

The mean surgical and tourniquet times of each group were 75 and 63 minutes (range, 65–100 and 50–80 minutes, respectively) in DLP type 1 group, 46 and 38 minutes (range, 40–65 and 30–50 minutes, respectively) in the DLP type 2 group, 45/40 minutes (range, 25–70 and 15–60 minutes, respectively) in the VLP group, respectively. The mean surgical and tourniquet times treated by DLP in the type 1 group were significantly longer (p < 0.05) than that of the VLP group.

Hardware selection for DLP was as follows: 9 dorsal H-framed plates (APTUS; TriLock dorsal distal radius plates, plate thickness: 1.6 mm; Medartis, Basel, Switzerland) which support both ulnar and radial columns from the dorsal surface as a dual-row plate, and 15 small dorsoulnar l-shaped plates, (APTUS: 9 cases, Stryker, Freiburg, Germany: 3 cases, DePuy Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland: 3 cases, plate thickness: range, 1.0–1.2 mm) which support the ulnar column. Implant removal was not performed except in considerably young patients or at the patient's request. Nine small l-shaped plates were removed, one for revision surgery with ulnar shortening osteotomy due to reduction loss of the DRUJ. Artificial bone grafting (beta-tricalcium phosphate) was performed in three patients with type 1 fractures who had a severe metaphyseal bone loss and rehabilitation was initiated within a few days. The wrist was rested on a thermoplastic splint with interval active range of motion (ROM) exercises. At 3 to 6 weeks, the thermoplastic splint was removed and progressive passive and strengthening exercises began. Outcomes were assessed clinically and radiographically. Clinical assessment was done by modified Mayo wrist score, ROM, grip strength, and complications. In radiographically, bone union rate, radiographic measurements, and loss of reduction were assessed.

Surgical Strategy and Technique

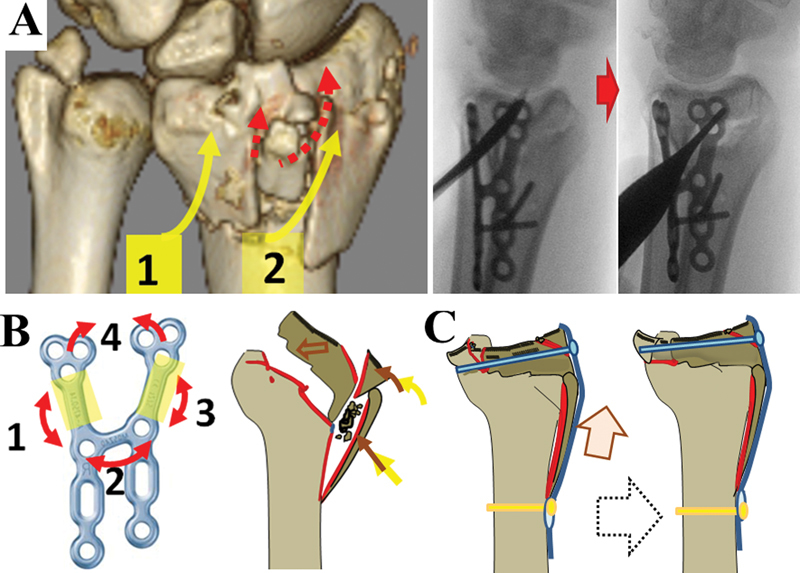

The surgical strategy for reduction and fixation by DLP is performed as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The fracture site is opened and reduced from the ulnar column first and the radial column second. The image in Fig. 4B shows the order of bending the H-framed plate to adapt the plate for correction and fixation of the displaced fragments. The use of the buttress effect on the distal half surface of the bent plate is useful for the reduction of elevated dorsal roof fragments, firmly depressed die-punch fragment. Additional bending of the distal end of the plate may be helpful to catch the rim fragment. In the treatment of type 1 fractures (Fig. 4A), in which the reduction of the radial column is necessary, the buttress effect of the distal half of the bent plate was applied on the radial side as well as on the ulnar column. Displaced radial styloid fragments could be reduced by manual compression. Elevation of the joint depression site could be done performed through the dorsal fracture gap, as shown in Fig. 4A. If necessary, bone graft materials may be used to provide an optimal bone void filler. As a general principal, K-wire was not used as a temporal fixation.

Fig. 4.

Schematic drawing of the surgical strategy of reduction and fixation in the displaced distal radius in the type 1 fracture. (A) Yellow arrows indicate the order of correction of the roof fragment by buttress effect. Red arrows indicate the pathway to elevate central depression of the articular surface. Central depression of the joint surface was elevated through fracture gap at the dorsal side as shown by radiograph during surgery. (B) The left figure shows the order of H-framed plate bending to adapt the plate for correction and fixation of the displaced fragments. (C) The final procedure to obtain precise joint correction by lengthening the radius through oblong holes and positioning the screw in a locking plate.

Fig. 5.

Schematic drawing of the surgical strategy of reduction and fixation of the displaced distal radius in the type 2 fracture. (A) Radial styloid fragments or crossing fracture lines at the volar surface were stabilized using a percutaneous cannulated screw. (B) Buttress reduction of the dorsal die-punch fragment through a limited DUC opening. DUC, dorsoulnar column.

Positioning screws secure the plate to the bone at the sliding holes at the distal side of the oblong hole. These screw holes permit alteration of plate position by using the sliding hole following the fixation of polyaxial (15 degrees in each direction) locking screws at the most distal holes adjacent to the radiocarpal joint. This procedure is similar to the condylar stabilization technique used in volar plating by Kiyoshige et al,11 for correcting alignment as shown in Fig. 4C. Additional locking screws were placed for more rigid fixation. Fig. 5 shows the general order of fixation in type 2 fractures. In this type, as displacement of RC was minimum, RC was reduced manually or using percutaneous K-wire. A styloid shearing fragment with crossing fracture lines at the volar surface was stabilized first using percutaneous screws and buttress reduction of the die-punch fragment was performed under direct vision through limited ulnar column opening second.

Results

Clinical Outcomes

Patient characteristics and clinical results are shown in Table 1. After a mean follow-up of 6 months, outcomes were good or excellent based on the modified Mayo wrist scores, except for one type 2 case (case 6 in Table 1). The mean ROM at 6 months of each type was as follows: in type 1, the mean palmar flexion was 50 degrees (range, 40–80 degrees), dorsiflexion was 70 degrees (range, 40–85 degrees), supination was 85 degrees (range, 60–90 degrees), and pronation was 80 degrees (range, 50–90 degrees); in type 2, the mean palmar flexion was 65 degrees (range, 45–85 degrees), dorsiflexion was 75 degrees (range, 55–85 degrees), supination was 85 degrees (range, 70–90 degrees), and pronation was 80 degrees (range, 55–90 degrees). The mean grip strength of the injured hand was 82.5% (range, 60–100%) of the uninjured side.

There were no cases of tendon rupture or neurovascular complications. The mild discomfort of the dorsum of the wrist was observed three cases in type 1 but the tenderness and swelling resolved with no rupture of the tendons within 6 months after surgery with no request for implant removal. Finally, patients did not experience minor complications associated with flexor or serious extensor tendon irritation or carpal tunnel syndrome.

Radiographical Assessment

The mean time to radiological union was 2.7 months (range, 2.0–6.0 months). There was no nonunion. At the time of union, the mean volar tilt was 5 degrees (range, −5 to 15 degrees), radial inclination was 18 degrees (range, 8–27 degrees), and ulnar plus variance was 0.5 mm (range, −1.0 to 2.0 mm).

Fracture reduction was lost in 2 of 24 patients (8.3%) treated with DLP for unstable dorsally displaced distal radius fractures and occurred within 1 month. One patient (case 6 in type 2) had a collapse of the dorsal ulnar fragment, resulting in a dorsal tilt of 5 degrees and limited forearm rotation, owing to technical failure. Initial postoperative radiographs showed acceptable joint congruity restoration and volar tilt. The dorsal plate was used as a buttress plate with no distal locking screws, resulting in a dorsoulnar fragment collapse. This patient underwent implant removal and ulnar shortening osteotomy at 12 months after surgery. Loss of reduction with depression of the articular surface of 2 mm at scapholunate facet occurred in one case (case 8 in type 1); however, clinical outcomes (i.e., ROM, pain, and the activity of affected hand) improved 3 months after surgery with positive overall outcomes. The displaced fragment recognized as adjacent to the dorsal die-punch fragment in the radial direction did not affect the clinical outcomes.

Discussion

Although the dorsal approach needs more complex procedure for the treatment of soft tissue compared with the volar approach, dorsal plating has an advantage for the correction and fixation of dorsally displaced fractures in selected cases.12 Recent improvements have made the locking plate thinner with a rounder edge, which has led to a lower complication rate.7 8 9 10

In this study, we showed the excellent results of low-profile DLP in both two types of fractures. The type 1 fracture causes dorsal shearing accompanied by compression force.13 In this type, the very distal small volar fragments are difficult to treat with volar plating and incomplete reduction of the dorsal roof fragment of the distal radius delay bone union, cause irritation, or lead to extensor pollicis longus rupture.14 We treated this fracture type with dual ray dorsal plating with favorable results. From a biomechanical point of view, the radial side supported by dorsal dual-ray plating seemed to be weak compared with radial plating; however, wide radial side exposure is invasive which complicates thin dorsal soft tissues coverage. Radial plating could irritate the extensor tendons of the first compartment or radial sensory branch.

The type 2 fracture includes subgroup B2.2 as classified by Muller et al.13 This type of fracture is caused by both dorsal shearing (group B2) and styloid shearing (group B1) force, which is often associated with vehicular trauma due to high-velocity impact, such as motorcycle trauma or falls from a great height. Isolated dorsal marginal fractures are extremely uncommon, as combined lesions of a radial styloid fracture and a dorsal marginal fracture are more common. In our study, the dorsal column was often accompanied by a radial column and volar fracture line with little displacement.

We obtained favorable clinical results, including radiographic bone union, without obvious complications with the loss of correction in 2 of 24 cases. In one case of type 2 fracture, the correction loss of dorsal die-punch fragment led to ulnar plus deformity, which caused ulnar wrist pain. In this case, we did not place the locking screw in the most distal hole of small l-plate. Following this case, we have used locking screws in all holes at the distal end and have not experienced further loss of correction. Reduction loss with joint depression sites was observed in one case of type 1 fracture but it did not affect clinical outcome. This situation could have been prevented by using bone graft to fill the bone void caused by joint elevation. The displaced fragment radially adjacent to the dorsal die-punch fragment, at the scapholunate facet, is a weak point of fixation due to the shape of the implant and transmitted load of radiocarpal joint. However, loss of this fragment alone seemed to have little effect on clinical outcomes, if it did not involve DRUJ displacement.

The mean postoperative palmar-flexion in type 1 fractures was 50 degrees at 6 months after surgery. Recovery after DLP treatment has been reported to be slow for ROM but complication rates are lower compared with VLP.15 Whether dorsal stiffness found during the slow recovery of palmar flexion in the type 1 fracture is caused by the dorsal approach, the dorsal implant (i.e., H-framed in this study), the severity of the injury itself, or both, remains unknown.

Although further refinements have been made to the dorsal plates that are lower in profile and less irritating to tendons, attention to surgical technique in dorsal plating is crucial. We planned the dorsal approach and the reduction technique from the exposure of the column, and the closure method in each layer, with an aim to prevent extensor tendon irritation, but allow fracture reduction and rigid fixation. Since subperiosteal elevation of the second and fourth extensor compartments and interposition of periosteum between the plate and extensor tendons at the time of closure is not always easy in the classical dorsal plating approach, we devised a dorsal retinacula technique using four flaps composed of three extensor retinaculum and one periosteal tissue-based on its ulnar attachment and allows coverage over the plate with no bowstringing of the extensor tendon.

In the treatment of the type 1 fracture, final elevation of the joint surface by lengthening the radius using positioning of the oblong hole of DLP increased the reduction accuracy of the articular surface (Fig. 4C). This procedure imitates the condylar stabilization technique used in VLP.11 In addition, catching and correction of the volar fragment on the opposite side could be performed using the dorsal condylar stabilization technique, in some cases. When treating dorsal displaced fractures using dorsal plating, dorsal buttress plating seemed to prevent dorsal subluxation of the carpus in some cases. In addition, after volar plating, displaced dorsal rim fractures have little effect on functional outcomes16; however, we experienced displaced ulnar rim fragments that were dorsally rotated, leading to subsidence of the articular surface with significant DRUJ incongruity disturbances. A correction to dorsal rim fragments may be beneficial in rare situations.

We postulated that small l-shaped DLP can treat type 2 fractures with a minimally invasive procedure. Limited opening of the ulnar column is easy and safe, and reduction and fixation of the radial styloid fragment through small incisions using the percutaneous screw technique is less invasive. The displacement of ulnar fragments can be difficult to detect correctly by X-ray film or fluoroscopy. Therefore, opening the ulnar column offers good visualization of displaced dorsal die-punch fragments and a precise reduction by the buttress effect of the plate.

A recent report described the limited benefits of dorsal plate fixation compared with other treatment options. In addition, they described that the dorsal plate group had greater complications with statistically higher levels of pain, weaker grip strength, and longer surgical and tourniquet times.17 However, longer surgical and tourniquet times are the only disadvantages of dorsal plating in treating type 1 fractures based on our review. The H-plate procedure offers excellent results without evident soft tissue irritation.

Although the surgical strategy described in this study is simple, the number of cases included was small. There are many complex types of distal radius fractures. Therefore, our strategy does not cover all unstable fractures and those cases must be managed using the techniques supported by the three-column theory advanced by Rikli and Regazzoni18 19 or through the use of implants and techniques specific to fragment-specific fixation.20 21 22 However, we believe that polyaxial screw positioning increases subchondral stability and allows more flexibility than fragment-specific fixation.

An epidemiological review showed a biphasic age at onset of distal radius fractures.23 The patients treated by DLP in this study included those in the younger male generation compared with the patients who received VLP. Higher energy shearing fractures of the end of the distal radius occur most commonly in young people, affecting males more than females, and are more likely to result in greater articular involvement and comminution. However, the overall age-adjusted incidence of distal radius fractures is frequent in women after the postmenopausal years, owing to a reduction in bone mass, and the incidence of comminuted intra-articular fractures increases in both sexes with advancing age. Both type 1 and type 2 fractures in our study correspond to the first and second peak ages and the first peak of younger age, respectively.

Level of Evidence

Therapeutic IV.

Conflict of Interest None.

Note

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. No funds were received in support of this study.

References

- 1.Earp B E, Foster B, Blazar P E. The use of a single volar locking plate for AO C3-type distal radius fractures. Hand (NY) 2015;10(4):649–653. doi: 10.1007/s11552-015-9757-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fok M W, Klausmeyer M A, Fernandez D L, Orbay J L, Bergada A L. Volar plate fixation of intra-articular distal radius fractures: a retrospective study. J Wrist Surg. 2013;2(3):247–254. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1350086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wichlas F, Haas N P, Disch A, Machó D, Tsitsilonis S. Complication rates and reduction potential of palmar versus dorsal locking plate osteosynthesis for the treatment of distal radius fractures. J Orthop Traumatol. 2014;15(4):259–264. doi: 10.1007/s10195-014-0306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dy C J, Wolfe S W, Jupiter J B, Blazar P E, Ruch D S, Hanel D P. Distal radius fractures: strategic alternatives to volar plate fixation. Instr Course Lect. 2014;63:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyllianakis M E, Panagopoulos A M, Saridis A. Long-term results of dorsally displaced distal radius fractures treated with the pi-plate: is hardware removal necessary? Orthopedics. 2011;34(7):e282–e286. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20110526-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gajdos R, Bozik M, Stranak P. Is an implant removal after dorsal plating of distal radius fracture always needed? Bratisl Lek Listy (Tlacene Vyd) 2015;116(6):357–362. doi: 10.4149/bll_2015_068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu Y R, Makhni M C, Tabrizi S, Rozental T D, Mundanthanam G, Day C S. Complications of low-profile dorsal versus volar locking plates in the distal radius: a comparative study. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(7):1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matzon J L, Kenniston J, Beredjiklian P K. Hardware-related complications after dorsal plating for displaced distal radius fractures. Orthopedics. 2014;37(11):e978–e982. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20141023-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutsky K, McKeon K, Goldfarb C, Boyer M. Dorsal fixation of intra-articular distal radius fractures using 2.4-mm locking plates. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2009;13(4):187–196. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181c15de2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutsky K, Boyer M, Goldfarb C. Dorsal locked plate fixation of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(7):1414–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiyoshige Y. Condylar stabilizing technique with AO/ASIF distal radius plate for Colles' fracture associated with osteoporosis. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2002;6(4):205–208. doi: 10.1097/00130911-200212000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavakolian J D, Jupiter J B. Dorsal plating for distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2005;21(3):341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jupiter J B. Complex articular fractures of the distal radius: classification and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(3):119–129. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zenke Y, Sakai A, Oshige T. et al. Extensor pollicis longus tendon ruptures after the use of volar locking plates for distal radius fractures. Hand Surg. 2013;18(2):169–173. doi: 10.1142/S0218810413500196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matschke S, Wentzensen A, Ring D, Marent-Huber M, Audigé L, Jupiter J B. Comparison of angle stable plate fixation approaches for distal radius fractures. Injury. 2011;42(4):385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J K, Cho S W. The effects of a displaced dorsal rim fracture on outcomes after volar plate fixation of a distal radius fracture. Injury. 2012;43(2):143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horst T A, Jupiter J B. Stabilisation of distal radius fractures: Lessons learned and future directions. Injury. 2016;47(2):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rikli D A, Regazzoni P. The double plating technique for distal radius fractures. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2000;4(2):107–114. doi: 10.1097/00130911-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rikli D A, Regazzoni P, Babst R. Management of complex distal radius fractures [in German] Zentralbl Chir. 2003;128(12):1008–1013. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medoff R J. Essential radiographic evaluation for distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2005;21(3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson L S, Minihane K P, Stern L D, Eller E, Seshadri R. The outcome of intra-articular distal radius fractures treated with fragment-specific fixation. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(8):1333–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geissler W B. Management distal radius and distal ulnar fractures with fragment specific plate. J Wrist Surg. 2013;2(2):190–194. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1341409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brogan D M, Richard M J, Ruch D, Kakar S. Management of severely comminuted distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(9):1905–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]