Abstract

Natural products, including botanical dietary supplements and exotic drinks, represent an ever-increasing share of the health care market. The parallel ever-increasing popularity of self-medicating with natural products increases the likelihood of co-consumption with conventional drugs, raising concerns for unwanted natural product-drug interactions. Assessing the drug interaction liability of natural products is challenging due to the complex and variable chemical composition inherent to these products, necessitating a streamlined preclinical testing approach to prioritize precipitant individual constituents for further investigation. Such an approach was evaluated in the current work to prioritize constituents in the model natural product, grapefruit juice, as inhibitors of intestinal organic anion-transporting peptide (OATP)-mediated uptake. Using OATP2B1-expressing MDCKII cells and the probe substrate estrone 3-sulfate, IC50s were determined for constituents representative of the flavanone (naringin, naringenin, hesperidin), furanocoumarin (bergamottin, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin), and polymethoxyflavone (nobiletin and tangeretin) classes contained in grapefruit juice juice. Nobiletin was the most potent (IC50, 3.7 μM); 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin, naringin, naringenin, and tangeretin were moderately potent (IC50, 20–50 μM); and bergamottin and hesperidin were the least potent (IC50, >300 μM) OATP2B1 inhibitors. Intestinal absorption simulations based on physiochemical properties were used to determine ratios of unbound concentration to IC50 for each constituent within enterocytes and to prioritize in order of pre-defined cut-off values. This streamlined approach could be applied to other natural products that contain multiple precipitants of natural product-drug interactions.

Keywords: OATP2B1, grapefruit juice, drug interaction, transporter, simulation

Introduction

Phytochemicals contained in botanical natural products, including citrus juices, teas, and herbal supplements, can precipitate pharmacokinetic interactions with conventional drugs by altering absorption and elimination processes, which can lead to altered systemic drug exposure and potentially, enhanced or reduced pharmacologic effect(s) [1–3]. Rigorous assessment of the drug interaction potential of specific constituents within natural products is challenging due to the complex and variable chemical composition inherent to these products [4]. There are no harmonized guidelines for assessing precipitant constituents within natural products, and pre-clinical and clinical testing of each constituent is neither practical nor efficient. These observations, combined with the ever-growing consumer and health care markets for botanical natural products, highlight the need for a streamlined approach to identify, screen, and prioritize high-risk constituents that can precipitate pharmacokinetic interactions with conventional drugs.

Grapefruit juice (GFJ) is an extensively studied natural product that inhibits the intestinal metabolism and/or transport of numerous drugs. The most rigorously studied mechanism underlying the GFJ effect is inhibition of the prominent intestinal drug metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A. A relatively less studied mechanism is inhibition of intestinal organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs) [5], uptake transporters located on the apical membranes of enterocytes that act to facilitate substrate absorption. Such OATP-mediated interactions can lead to a significant decrease in systemic exposure to substrate drugs (e.g., fexofenadine, fluoroquinolone antimicrobials, beta-blockers, and aliskiren), potentially leading to reduced therapeutic effect [6–10]. Natural product-drug interactions mediated via inhibition of intestinal OATPs are not limited to GFJ. For example, orange juice and apple juice have been shown to significantly reduce the systemic exposure to fexofenadine, some beta-blockers, and aliskiren by at least 50% [7, 11, 12]. More recently, constituents in a green tea beverage were reported to decrease systemic exposure to the beta-blocker, nadolol, by 85% in healthy volunteers by inhibiting intestinal OATP1A2, albeit the existence of this transporter is controversial [13, 14]; this reduction in systemic exposure was accompanied by an attenuated reduction in systolic blood pressure [9]. These observations prompted evaluation of a streamlined approach for pre-clinical testing of candidate intestinal OATP inhibitors using GFJ as an archetypal, well-characterized natural product with successful in vitro-in vivo extrapolated drug interaction liability.

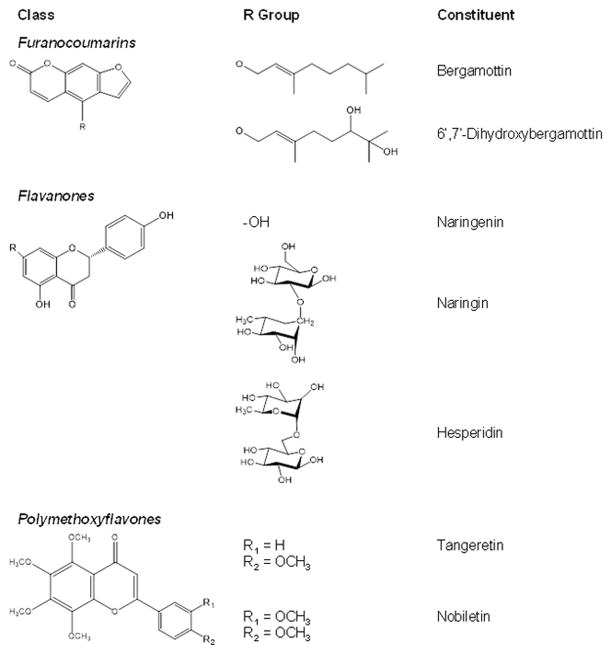

The flavanone naringin is the only isolated GFJ constituent that has been tested as an intestinal OATP inhibitor in human subjects. When administered to healthy volunteers as an aqueous naringin solution (~1.2 mM) or an equimolar concentration in GFJ, naringin alone did not fully reproduce the decrease in the area under the concentration-time curve of the OATP substrate fexofenadine, suggesting that other constituents contribute to the effect of whole juice [15]. A second clinical study involving a modified GFJ devoid of furanocoumarins and polymethoxyflavones showed similar effects as the original GFJ on the pharmacokinetics of fexofenadine [16], suggesting that flavanones are the major OATP inhibitors. Based on these clinical observations, constituents representative of the three chemical classes (Fig. 1) were tested to determine whether the proposed method could accurately identify and exclude clinically relevant OATP inhibitors. Results ultimately could contribute to the generation of a decision tree for systematically identifying and prioritizing intestinal OATP inhibitors for further investigation.

Fig. 1.

Structures of constituents from representative chemical classes contained in grapefruit juice.

Materials and Methods

Materials and chemicals

[3H]Estrone 3-sulfate ammonium salt (54.3 Ci/mmol, purity >97%) was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA). Estrone 3-sulfate potassium salt, D-glucose, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin (DHB), bergamottin, naringin, hesperidin, tangeretin, and nobiletin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Hanks’ balanced salt solution with calcium and magnesium was purchased from Mediatech Inc. (Hendon, VA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); fetal bovine serum; trypsin-EDTA; HEPES; and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 4.5 g/L D-glucose, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). MDCKII parental cells and stably transfected MDCKII-OATP2B1 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Markus Grube (Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University, Greifswald, Germany). All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Ethical approval was not required for the following in vitro and in silico research activities.

Cell culture

Parental MDCKII and stably transfected MDCKII-OATP2B1 cells were cultured and maintained as described previously [17]. Cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well and grown to confluence for 2–3 days prior to experimentation.

IC50 determination

Cells were washed and preincubated for 30 min at 37°C in uptake buffer (125 mM NaCl, 48 mM KCl, 5.6 mM D-glucose, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 12 mM MgSO4, and 25 mM MES, pH 6). Buffer was replaced, and cells were treated with a solution (200 μL) consisting of radiolabeled (0.27 μCi/well) plus unlabeled estrone 3-sulfate (total concentration, 1 μM) and GFJ constituent (0 to 316 μM). After 3 min at 37°C, cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and lysed with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide/0.1% SDS. Cell lysate aliquots (200 μL) were added to liquid scintillation cocktail (5 mL), and radioactivity was counted. Protein concentrations were determined with a BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Estrone 3-sulfate uptake was linear up to 5 min (data not shown).

Data analysis

Uptake rates were normalized to protein content. Net OATP2B1-mediated estrone 3-sulfate uptake was calculated by subtracting uptake in parenteral cells (OATP2B1-negative) from uptake in OATP2B1-expressing cells. Percent control activity was calculated relative to vehicle (3% methanol), which was set at 100% uptake. Initial estimates of apparent IC50s were determined from linear regression of net substrate uptake vs. natural logarithm of GFJ constituent concentration data. IC50s were recovered by fitting the inhibitory Emax model (equation 1 or 2) with untransformed data using Phoenix® WinNonlin® (v7.0, Certara, Princeton, NJ):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where E and E0 denote maximum (i.e., observed) and baseline effects, respectively; Imax denotes the maximum inhibitory effect; C denotes inhibitor concentration; and γ denotes the Hill coefficient. Robustness of model fits was assessed from visual check of observed and predicted data, distribution of residuals, Akaike information criteria, and standard errors. Experimental data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate determinations. IC50s are presented as estimate ± standard error of the estimates.

Simulations

GFJ constituent absorption into enterocytes was simulated to assess relative OATP-mediated interaction liability according to the decision trees set forth by the International Transporter Consortium [18]. Simulations were used to estimate [I]ent/IC50 and [I]GFJ/IC50, where [I]ent is the maximum unbound constituent concentration in the simulated enterocyte compartment; [I]GFJ is the maximum reported constituent concentration in GFJ (i.e., the theoretical maximum concentration in the gastrointestinal lumen) (Table 1); and IC50 is the half-maximal inhibitory concentration measured for OATP2B1 in the current work.

Table 1.

Absorption model inputs

| Naringin | Naringenin | Hesperidin | DHB | Bergamottin | Nobiletin | Tangeretin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [I]GFJ (μM)

|

|||||||

| 6540 [38] | 595 [39] | 117 [30] | 52.5 [40] | 36.6 [40] | 28.4* [41] | 78.4* [42] | |

| Predicted physicochemical properties

|

|||||||

| Molar mass (daltons) | 580.55 | 272.257 | 610.57 | 372.42 | 338.397 | 402.39 | 370.36 |

| pKa | 9.94; 8.10 | 9.81; 9.12 7.38 |

9.71; 8.10 | - | - | - | - |

| Diffusion coefficient | 0.56 | 0.86 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.71 |

| O:W partition | −0.26 | 2.42 | −0.33 | 2.79 | 5.85 | 2.77 | 2.92 |

| O:W distribution | −0.34 | 2.10 | −0.40 | 2.79 | 5.85 | 2.77 | 2.92 |

| Peff (cm/s × 104) | 0.12 | 2.99 | 0.13 | 1.08 | 2.12 | 2.55 | 2.75 |

| SW (mg/mL) | 4.37 | 0.31 | 4.89 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SLgastric fast (mg/mL) | 1.27 | 0.13 | 1.09 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| SLgut fast (mg/mL) | 1.46 | 0.36 | 1.31 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| SLgut fed (mg/mL) | 2.26 | 0.58 | 1.96 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Simulated fa (%)

|

|||||||

| 27.27 | 99.65 | 44.58 | 98.62 | 99.83 | 99.90 | 99.94 | |

[I]GFJ, maximum reported concentration in grapefruit juice. O:W partition, octanol-water partition coefficient. O:W distribution, octanol-water distribution coefficient. Peff, effective human jejunal permeability coefficient. SW, native water solubility. SLgastric fast, solubility in GastroPlus™ simulated gastric fluid in the fasted state. SLgut fast, solubility in simulated intestinal fluid in the fasted state. SLgut fed, solubility in simulated intestinal fluid in the fed state. DHB, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin. fa, fraction of the dose absorbed into enterocytes.

Concentration in flavedo (peel).

Structure-based physicochemical properties for each GFJ constituent were predicted using MedChem Designer™ 4.0 (Simulations Plus, Inc., Lancaster, CA) (Table 1). These values were used to populate the Advanced Compartmental Absorption and Transit (ACAT) model within GastroPlus™ (v9.0.0007, Simulations Plus). The ACAT model expands upon the traditional compartmental absorption and transit model [19] by predicting dissolution, ionization, and pH-dependent solubility in simulated gastrointestinal fluid, as well as binding parameters and partition coefficients for multiple enterocyte compartments along the intestinal tract. The model was populated using the default physiology for a fasted 35-year-old healthy man. Specifying the physiology was necessary to create a simulated enterocyte compartment within GastroPlus™; however, neither age nor sex substantially alter intracellular xenobiotic concentrations within the enterocyte compartment produced by the ACAT model. Absorption of a single dose of each constituent was simulated as an immediate-release solution (250 mL) at [I]GFJ (Table 1). Gastric transit time was set at 0.1 h as appropriate for a liquid dosage form. Constituent particle density and mean precipitation time were set at the default values of 1.2 g/mL and 900 s, respectively. OATP2B1 expression and activity were assumed to be homogenous throughout the intestinal tract [13]; thus, [I]ent values represent the average for the entire intestinal compartment. Regulatory guidelines for intestinal transporters specify that [I]1/IC50 ≥ 0.1 (in this case, [I]ent/IC50 ≥ 0.1) or [I]2/IC50 ≥ 10 (in this case, [I]GFJ/IC50 ≥ 10) merits a clinical interaction study [18, 20]; as such, ratios are presented in reference to these cutoff values (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the [I]ent/IC50 and [I]GFJ/IC50 ratios for grapefruit juice (GFJ) constituents as inhibitors of intestinal OATP2B1. [I]ent/IC50 (gray), ratio of the unbound concentration in simulated enterocyte compartments to IC50. [I]GFJ/IC50 (orange), ratio of maximum constituent concentration in GFJ to IC50. The absorption simulation predicted [I]ents of 560 (naringin), 63.9 (naringenin), 16.8 (hesperidin), 2.28 (DHB), 2.78 (bergamottin), 3.71 (nobiletin), and 8.85 (tangeretin) μM. Gray and orange lines denote ratios at which a clinical interaction study is suggested for each metric: [I]ent/IC50, 0.1 (gray); [I]GFJ/IC50, 10 (orange). DHB, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin. Red circles indicate constituents whose ratios exceeded these threshold values.

Results

Nobiletin was the most potent OATP2B1 inhibitor, with an IC50 of <5 μM (Fig. 2A). Naringenin was moderately potent, with an IC50 of 20 μM (Fig. 2B). DHB (Fig. 2C), naringin (Fig. 2D), and tangeretin (Fig. 2E) were approximately equipotent, with IC50s ranging from 34 to 40 μM. Bergamottin (Fig. 2F) and hesperidin (Fig. 2G) were the least potent OATP2B1 inhibitors, with IC50s >300 μM. With the exception of nobiletin and bergamottin, all of the constituents stimulated estrone 3-sulfate uptake by as much as 20% at concentrations ranging from <1 to 3 μM. The absorption simulation-predicted [I]ent for naringin, naringenin, hesperidin, DHB, bergamottin, nobiletin, and tangeretin were, respectively, 560, 63.9, 16.8, 2.28, 2.78, 3.71, and 8.85 μM. The [I]ent/IC50 for naringenin, naringin, nobiletin, and tangeretin exceeded 0.1 (Fig. 3). The [I]GFJ/IC50 for naringenin and naringin exceeded 10.

Fig. 2.

Concentration-dependent modulation of OATP2B1-mediated estrone-3-sulfate uptake by grapefruit juice constituents representative of three chemical classes (A–G). Percent control activity is relative to vehicle condition. Symbols and error bars denote means and standard errors, respectively, of triplicate incubations. Curves denote nonlinear least-squares regression of observed data.

Discussion

An increasing number of intestinal and hepatic OATP inhibitors have been identified in botanical natural products, including GFJ, other fruit juices, and green tea [21–26]. Systematic evaluation of the inhibitory effect of each of the many constituents contained in a given natural product using a single in vitro system, and especially human subjects, in a time- and cost-efficient manner is impossible. Because harmonized guidelines do not exist for prioritizing precipitant natural product constituents, an in vitro-in silico streamlined approach was developed using GFJ as a test natural product. IC50s for representative GFJ constituents from three distinct chemical classes were determined using an established OATP2B1-transfected cell system and probe substrate (Fig. 2). These data, combined with results from simulations of intestinal absorption, were used to prioritize constituents based on the unbound concentration/IC50 ratio. The IC50s recovered for DHB, naringenin, naringin, nobiletin, and tangeretin were below the maximum reported concentration in grapefruit juice ([I]GFJ) (Table 1), supporting these constituents as potential clinically relevant intestinal OATP inhibitors. However, simple comparison of the IC50 with [I]GFJ is theoretically not as robust for predicting clinical interactions as a comparison with the unbound concentration at the site of enterocyte uptake ([I]ent). Such an approach has been suggested for hepatic transporters [27] and should be more predictive of the likelihood of an interaction in vivo. A similar strategy was taken in the current work to evaluate the drug interaction liability of GFJ constituents at the site of intestinal absorption.

As mentioned earlier, flavanones are likely the major OATP inhibitors in GFJ, which was confirmed by both metrics ([I]GFJ/IC50 and [I]ent/IC50). Hesperidin was the only flavanone not identified by either metric, probably due to having a relatively low [I]GFJ [28–31]; however, hesperidin may pose an interaction risk when consumed in orange juice, in which [I]GFJ approaches 2 mM [32]. Both metrics correctly excluded the furanocoumarins as OATP inhibitors in GFJ. All of the constituents except nobiletin and bergamottin stimulated estrone 3-sulfate uptake by as much as 20% at the lower concentrations tested (<1 to 3 μM). OATP stimulation has been observed with other natural product constituents [21, 24, 25] and may be attributed to multiple binding sites or conformational changes, which could lead to enhanced uptake by OATP.

The IC50s recovered in the current work differed somewhat from those recovered using OATP2B1-overexpressing Xenopus laevis oocytes [33]. For example, hesperidin showed no inhibition at the concentrations tested in MDCKII cells (current work), but was a potent inhibitor in oocytes (IC50, >300 vs. 1.92 μM). Differences in membrane permeability, intra- and extracellular non-specific binding, and/or transporter localization and trafficking between the two model systems could account for this discrepancy. Because the mechanism of OATP inhibition by flavonoids is not completely known, studies comparing OATP2B1 function between model systems are needed to clarify the ability of each to appropriately rank these intestinal OATP2B1 inhibitors.

Unlike the [I]GFJ/IC50 ratio, the [I]ent/IC50 ratio additionally identified the polymethoxyflavones nobiletin and tangeretin as possible precipitants of OATP-mediated GFJ-drug interactions, highlighting two areas for further research. First, it is unclear which ratio is more predictive of the likelihood of intestinal OATP2B1 inhibition in vivo. Although both ratios were adapted from decision trees set forth by the International Transporter Consortium [18], studies elucidating mechanisms of OATP2B1 inhibition should aid in selection of the most appropriate ratio and refinement of the cutoff criteria. Second, studies of drug interaction liability of individual constituents within the native environment of the natural product are warranted to determine synergistic, additive, and/or antagonistic effects. For example, it is possible that the inhibitory effects of the polymethoxyflavones are overwhelmed by those of the more abundant flavanones in GFJ. Studies comparing juices enriched in polymethoxyflavones relative to flavanones would provide further insight.

Conclusion

A streamlined approach for prioritizing intestinal OATP inhibitors in a complex natural product was demonstrated using the model natural product GFJ, an established OATP2B1-expressing cell system, and candidate inhibitors representative of three chemical classes. Using in silico-predicted rather than experimentally-measured physicochemical properties contributed to the high-throughput nature of this approach. Further refinement of this approach, including addressing uncertainties in calculated physicochemical properties, may contribute to the development of a decision tree for intestinal uptake transporter-based interactions, similar to that used for interactions mediated by inhibition of the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein [34]. This approach may be applied to natural products for which candidate precipitants are unknown, in which case high throughput analytical chemistry procedures [35–37] can be used a priori to identify bioactive constituents. Collaborations between clinical pharmacologists and natural products chemists would expedite this process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R01 GM077482] and National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [Grant UL1TR000083]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

The authors thank Dr. Markus Grube (Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University, Greifswald, Germany) for providing MDCKII parental cells and stably transfected MDCKII-OATP2B1 cells. Transfection work was completed while K.K. was affiliated with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. M.F.P. dedicates this article to Dr. David P. Paine.

Nonstandard abbreviations

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DHB

6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin

- GFJ

grapefruit juice

- MDCKII

Madin-Darby canine kidney type II

- OATP

organic anion-transporting polypeptide

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rodriguez-Fragoso L, Martinez-Arismendi JL, Orozco-Bustos D, Reyes-Esparza J, Torres E, Burchiel SW. Potential risks resulting from fruit/vegetable-drug interactions: effects on drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters. J Food Sci. 2011;76:R112–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurley BJ, Fifer EK, Gardner Z. Pharmacokinetic herb-drug interactions (part 2): drug interactions involving popular botanical dietary supplements and their clinical relevance. Planta Med. 2012;78:1490–514. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurley BJ. Pharmacokinetic herb-drug interactions (part 1): origins, mechanisms, and the impact of botanical dietary supplements. Planta Med. 2012;78:1478–89. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Won CS, Oberlies NH, Paine MF. Mechanisms underlying food-drug interactions: inhibition of intestinal metabolism and transport. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;136:186–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.08.001. S0163-7258(12)00162-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dresser GK, Bailey DG, Leake BF, Schwarz UI, Dawson PA, Freeman DJ, Kim RB. Fruit juices inhibit organic anion transporting polypeptide-mediated drug uptake to decrease the oral availability of fexofenadine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71:11–20. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.121152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenblatt DJ. Analysis of drug interactions involving fruit beverages and organic anion-transporting polypeptides. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:1403–7. doi: 10.1177/0091270009342251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey DG. Fruit juice inhibition of uptake transport: a new type of food-drug interaction. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:645–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolton MJ, Roufogalis BD, McLachlan AJ. Fruit juices as perpetrators of drug interactions: the role of organic anion-transporting polypeptides. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:622–30. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misaka S, Yatabe J, Muller F, Takano K, Kawabe K, Glaeser H, Yatabe MS, Onoue S, Werba JP, Watanabe H, Yamada S, Fromm MF, Kimura J. Green tea ingestion greatly reduces plasma concentrations of nadolol in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95:432–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An G, Mukker JK, Derendorf H, Frye RF. Enzyme- and transporter-mediated beverage-drug interactions: An update on fruit juices and green tea. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55:1313–31. doi: 10.1002/jcph.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tapaninen T, Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M. Grapefruit juice greatly reduces the plasma concentrations of the OATP2B1 and CYP3A4 substrate aliskiren. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:339–42. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapaninen T, Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M. Orange and apple juice greatly reduce the plasma concentrations of the OATP2B1 substrate aliskiren. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:718–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drozdzik M, Groer C, Penski J, Lapczuk J, Ostrowski M, Lai Y, Prasad B, Unadkat JD, Siegmund W, Oswald S. Protein abundance of clinically relevant multidrug transporters along the entire length of the human intestine. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:3547–55. doi: 10.1021/mp500330y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J, Michaud V, Moya LG, Gaudette F, Leung YH, Turgeon J. Effects of beta-blockers and tricyclic antidepressants on the activity of human organic anion transporting polypeptide 1A2 (OATP1A2) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;352:552–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.219287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey DG, Dresser GK, Leake BF, Kim RB. Naringin is a major and selective clinical inhibitor of organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1A2 (OATP1A2) in grapefruit juice. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:495–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Won CS, Lan T, Vandermolen KM, Dawson PA, Oberlies NH, Widmer WW, Scarlett YV, Paine MF. A modified grapefruit juice eliminates two compound classes as major mediators of the grapefruit juice-fexofenadine interaction: an in vitro-in vivo “connect”. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:982–90. doi: 10.1002/jcph.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grube M, Kock K, Karner S, Reuther S, Ritter CA, Jedlitschky G, Kroemer HK. Modification of OATP2B1-mediated transport by steroid hormones. Mol Pharm. 2006;70:1735–41. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Transporter C. Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KL, Chu X, Dahlin A, Evers R, Fischer V, Hillgren KM, Hoffmaster KA, Ishikawa T, Keppler D, Kim RB, Lee CA, Niemi M, Polli JW, Sugiyama Y, Swaan PW, Ware JA, Wright SH, Yee SW, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Zhang L. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–36. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu LX, Crison JR, Amidon GL. Compartmental transit and dispersion model analysis of small intestinal transit flow in humans. Int J Pharm. 1996;140:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Zhang YD, Strong JM, Reynolds KS, Huang SM. A regulatory viewpoint on transporter-based drug interactions. Xenobiotica. 2008;38:709–24. doi: 10.1080/00498250802017715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Wolkoff AW, Morris ME. Flavonoids as a novel class of human organic anion-transporting polypeptide OATP1B1 (OATP-C) modulators. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1666–72. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchikami H, Satoh H, Tsujimoto M, Ohdo S, Ohtani H, Sawada Y. Effects of herbal extracts on the function of human organic anion-transporting polypeptide OATP-B. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:577–82. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.007872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandery K, Balk B, Bujok K, Schmidt I, Fromm MF, Glaeser H. Inhibition of hepatic uptake transporters by flavonoids. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;46:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth M, Timmermann BN, Hagenbuch B. Interactions of green tea catechins with organic anion-transporting polypeptides. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:920–6. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.036640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roth M, Araya JJ, Timmermann BN, Hagenbuch B. Isolation of modulators of the liver-specific organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs) 1B1 and 1B3 from Rollinia emarginata Schlecht (Annonaceae) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:624–32. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandery K, Bujok K, Schmidt I, Keiser M, Siegmund W, Balk B, Konig J, Fromm MF, Glaeser H. Influence of the flavonoids apigenin, kaempferol, and quercetin on the function of organic anion transporting polypeptides 1A2 and 2B1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1746–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu X, Korzekwa K, Elsby R, Fenner K, Galetin A, Lai Y, Matsson P, Moss A, Nagar S, Rosania GR, Bai JPF, Polli JW, Sugiyama Y, Brouwer KLR Consortium IT. Intracellular Drug Concentrations and Transporters: Measurement, Modeling, and Implications for the Liver. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:126–141. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross SA, Ziska DS, Zhao K, ElSohly MA. Variance of common flavonoids by brand of grapefruit juice. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:154–61. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(99)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peterson JJ, Beecher GR, Bhagwat SA, Dwyer JT, Gebhardt SE, Haytowitz DB, Holden JM. Flavanones in grapefruit, lemons, and limes: A compilation and review of the data from the analytical literature. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;19:S74–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uckoo RM, Jayaprakasha GK, Balasubramaniam VM, Patil BS. Grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macfad) Phytochemicals Composition Is Modulated by Household Processing Techniques. J Food Sci. 2012;77:C921–C926. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu YH, Zhang CW, Bucheli P, Wei DZ. Citrus flavonoids in fruit and traditional Chinese medicinal food ingredients in China. Plant Food Hum Nutr. 2006;61:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s11130-006-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomas-Barberen FA, Clifford MN. Flavanones, chalcones and dihydrochalcones - nature, occurrence and dietary burden. J Sci Food Agr. 2000;80:1073–1080. doi: 10.1002/(Sici)1097-0010(20000515)80:7<1073::Aid-Jsfa568>3.0.Co;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shirasaka Y, Shichiri M, Mori T, Nakanishi T, Tamai I. Major active components in grapefruit, orange, and apple juices responsible for OATP2B1-mediated drug interactions. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102:3418–26. doi: 10.1002/jps.23653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellens H, Deng SB, Coleman J, Bentz J, Taub ME, Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Chung SP, Heredi-Szabo K, Neuhoff S, Palm J, Balimane P, Zhang L, Jamei M, Hanna I, O’Connor M, Bednarczyk D, Forsgard M, Chu XY, Funk C, Guo AL, Hillgren KM, Li LB, Pak AY, Perloff ES, Rajaraman G, Salphati L, Taur JS, Weitz D, Wortelboer HM, Xia CQ, Xiao GQ, Yamagata T, Lee CA. Application of Receiver Operating Characteristic Analysis to Refine the Prediction of Potential Digoxin Drug Interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:1367–1374. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azzollini A, Favre-Godal Q, Zhang J, Marcourt L, Ebrahimi SN, Wang S, Fan P, Lou H, Guillarme D, Queiroz EF, Wolfender JL. Preparative Scale MS-Guided Isolation of Bioactive Compounds Using High-Resolution Flash Chromatography: Antifungals from Chiloscyphus polyanthos as a Case Study. Planta Med. 2016;82:1051–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-108207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wenderski TA, Stratton CF, Bauer RA, Kopp F, Tan DS. Principal component analysis as a tool for library design: a case study investigating natural products, brand-name drugs, natural product-like libraries, and drug-like libraries. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1263:225–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kellogg JJ, Todd DA, Egan JM, Raja HA, Oberlies NH, Kvalheim OM, Cech NB. Biochemometrics for Natural Products Research: Comparison of Data Analysis Approaches and Application to Identification of Bioactive Compounds. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:376–86. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brill S, Zimmermann C, Berger K, Drewe J, Gutmann H. In vitro interactions with repeated grapefruit juice administration--to peel or not to peel? Planta Med. 2009;75:332–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1112210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho PC, Saville DJ, Coville PF, Wanwimolruk S. Content of CYP3A4 inhibitors, naringin, naringenin and bergapten in grapefruit and grapefruit juice products. Pharm Acta Helv. 2000;74:379–85. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6865(99)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Castro WV, Mertens-Talcott S, Rubner A, Butterweck V, Derendorf H. Variation of flavonoids and furanocoumarins in grapefruit juices: a potential source of variability in grapefruit juice-drug interaction studies. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:249–55. doi: 10.1021/jf0516944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozaki K, Ishii T, Koga N, Nogata Y, Yano M, Ohta H. Quantification of nobiletin and tangeretin in citrus by micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography. Food Sci Technol Res. 2006;12:284–289. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rouseff RL, Ting SV. Tangeretin content of Florida citrus peel as determined by HPLC. Proc Fla State Hort Soc. 1979;92:145–148. [Google Scholar]