Abstract

Background

Genetically-engineered pigs could provide a source of kidneys for clinical transplantation. The two longest kidney graft survivals reported to date have been 136 days and 310 days, but graft survival >30 days has been unusual until recently.

Methods

Donor pigs (n=4) were on an α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout (GTKO)/human complement-regulatory protein (CD46) background (GTKO/CD46). In addition, the pigs were transgenic for at least one human coagulation-regulatory protein. Two baboons received a kidney from a 6-gene pig (Group A) and two from a 3-gene pig (Group B). Immunosuppressive therapy was identical in all 4 cases, and consisted of anti-thymoglobulin (ATG) + anti-CD20mAb (induction) and anti-CD40mAb + rapamycin + corticosteroids (maintenance). Anti-TNF-α and anti-IL-6R mAbs were administered to reduce the inflammatory response. Baboons were followed by clinical/laboratory monitoring of immune/coagulation/inflammatory/physiological parameters. At biopsy or euthanasia, the grafts were examined by microscopy.

Results

The two Group A baboons remained healthy with normal renal function >7 and >8 months, respectively, but then developed infectious complications. However, no features of a consumptive coagulopathy, e.g., thrombocytopenia, reduction of fibrinogen, or of a protein-losing nephropathy were observed. There was no evidence of an elicited anti-pig antibody response, and histology of biopsies taken at approximately 4, 6, and 7 months and at necropsy showed no significant abnormalities. In contrast, both Group B baboons developed features of a consumptive coagulopathy and required euthanasia on day 12.

Conclusions

The combination of (i) a graft from a specific 6-gene genetically-modified pig, (ii) an effective immunosuppressive regimen, and (iii) anti-inflammatory therapy prevented immune injury, a protein-losing nephropathy, and coagulation dysfunction for >7 months. Although the number of experiments is very limited, our impression is that expression of human endothelial protein C receptor (+/− CD55) in the graft is important if coagulation dysregulation is to be avoided.

Keywords: Anti-IL-6R antagonist, Costimulation blockade, Kidney, Pig, genetically engineered, Xenotransplantation

INTRODUCTION

Pig kidney graft survival in nonhuman primates (NHPs) has recently increased significantly.1–3 This has largely been associated with (i) the increasing availability of pigs with genetic modifications, and (ii) effective immunosuppressive therapy based on costimulation blockade, which together provide protection to the pig tissues from the primate immune response and/or molecular incompatibilities.

Before 2015, the longest survival of a pig kidney graft in a NHP was 90 days,4 though graft survival >30 days was unusual.1,2 In 2015, Higginbotham et al. reported prolonged survival (>125 days) of two rhesus monkeys following the transplantation of kidneys from α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout (GTKO) pigs expressing the human complement-regulatory protein CD55 (GTKO/CD55 pigs).5 The monkeys had been selected for their low titers of anti-pig antibodies. Immunosuppression was provided by an anti-CD154mAb-based regimen. There was no evidence of rejection or other pathology on renal biopsies on day 100. One monkey survived for 10 months at which time the graft failed with histopathological features of acute humoral xenograft rejection (Adams A, personal communication). In contrast to previous reports, features of consumptive coagulopathy and proteinuria were delayed for many months.

In contrast, one baboon with high anti-pig antibody levels (administered the anti-CD154-based regimen) and two baboons with low anti-pig antibody levels but treated with a belatacept-based regimen, lost their grafts within 3 weeks.5

In our own center, the transplantation of kidneys from GTKO/CD46 pigs in baboons (not selected for low anti-pig antibody levels) receiving an anti-CD154mAb-based regimen was invariably followed by the early development of a consumptive coagulopathy, and all recipients required euthanasia within 16 days.6 However, in 2015 we reported the transplantation of a kidney from a GTKO/CD46/CD55/thrombomodulin/endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR)/CD39 pig (though thrombomodulin and CD39 were very poorly expressed in the kidney) in a baboon with high titers of anti-nonGal IgM that functioned for 136 days.7 This encouraging result was obtained with an anti-CD40mAb-based regimen. The baboon died from a septic complication associated with a Myroides spp. Infection.7,8

We here report life-supporting kidney transplantation in 4 baboons, all selected on the basis of having low anti-pig (nonGal) antibody levels. All were administered the identical anti-CD40mAb-based regimen. Prolonged survival was obtained in two baboons with kidneys from a 6-gene pig (though with a different combination of genetic modifications than described above). Renal function remained normal in the baboons at >7 and >8 months, respectively, and there were minimal features of a protein-losing nephropathy. Unfortunately, both baboons developed features of infection from which one died (>7 months) and one required euthanasia (>8 months). In the two other baboons treated with the identical immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory regimen, but that received kidneys from a pig with only three genetic manipulations, consumptive coagulopathy developed within 12 days, requiring euthanasia.

We use this small study (with such discrepant outcomes) to discuss which factors may be important for pig kidney graft survival. Our tentative major conclusion is that expression of human EPCR (+/− CD55) in the kidney may be of importance.

METHODS

Animals

Pigs

Two genetically-engineered pigs (one with 6 and one with 3 genetic modifications; Revivicor, Blacksburg, VA), weighing 16kg (aged 2 months) and 18kg (aged 3 months), both of nonA(O) blood group, served as sources of kidney grafts (Table 1).9 Both pig donors were CMV-negative.

Table 1.

Genetic modifications of donor pigs and kidney graft survival in baboons

| Baboon | Donor pig gene phenotype (a) | Pre-transplant anti-pig antibody (relative MFI) (b) | Survival (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | |||

| B17315 | GTKO/CD46/CD55/EPCR/TFPI/CD47 | IgM 3.0; IgG 0.9 | 237 (Infection) (c) |

| B17615 | GTKO/CD46/CD55/EPCR/TFPI/CD47 | IgM 2.2; IgG 0.8 | 260 (infection) (d) |

| Group B | |||

| B17415 | GTKO/CD46/TBM | IgM 2.0; IgG 0.9 | 12 (CC) |

| B17515 | GTKO/CD46/TBM | IgM 2.5; IgG 0.9 | 12 (CC) |

CC: comsumptive coagulopathy

all pigs were of non-A (O) blood type.

in a group of 14 SPF baboon sers from which the 4 sera were selected, the mean relative MFI IgM and IgG levels were 4.0 and 1.0, respectively, and the ranges were 2.0–7.9 (IgM) and 0.8–1.4 (IgG), respectively.

peritonitis (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus and enterococcus faecium) 2 weeks after third abdominal operative procedure

pneumocystis pneumonia

The 6-gene-modified pig was GTKO and expressed two human complement-regulatory proteins (CD46/CD55), two human coagulation-regulatory proteins (EPCR and tissue factor pathway inhibitor [TFPI]) as well as CD47. (Expression of human CD47 in the pig graft may inhibit macrophage activation through its inhibitory effect on signal-regulatory protein alpha [SIRP-α], and may reduce inflammation and graft injury.10–12

The 3-gene-modified pig was GTKO/CD46 and expressed a single human coagulation-regulatory protein (thrombomodulin), which was inserted on a porcine thrombomodulin promoter (cloned from cells provided by LMU [Munich, Germany] on Revivicor’s GTKO/CD46 background). 9,13,14

The CD46 transgene was controlled by the endogenous human CD46 promoter, whereas the other transgenes (CD55, CD47, EPCR, and TFPI) were incorporated into multicistronic 2A-based vectors under control of the constitutive CAG promoter. Transgene expression was determined by flow cytometry of pig aortic endothelial cells (pAECs).

Baboons

Four baboons (Papio anubis) from the specific pathogen-free colony at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (Oklahoma City, OK),15 weighing 7–9kg, of blood group B were recipients of pig kidneys. All 4 were selected on the basis of having low anti-pig antibody levels. Two baboons (B17315 and B17615; Group A) received kidneys from the 6-gene pig, and two baboons (B17415 and B17515; Group B) received kidneys from the 3-gene pig (Table 1). Although we did not test the CMV status of the 4 baboons pre-transplantation, they all received ganciclovir i.v. (while i.v. lines were in place) or valganciclovir p.o. (after line removal) throughout the entire course of the experiments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Immunosuppressive, anti-inflammatory, and adjunctive therapy

| Agent | Dose (Duration) |

|---|---|

| Immunosuppressive | |

| Induction: | |

| Thymoglobulin (ATG) (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) | 10mg/kg (day −3) (to reduce the CD3+T cell count to <500/mm3) |

| Anti-CD20mAb (Rituximab) (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) | 10mg/kg (day −2) |

| Cobra venom factor (n=2) (Complement Technology, Tyler, Texas) | 100IU (days −1 and 0) |

| Maintenance: | |

| Anti-CD40mAb (2C10R4) (NIH NHP Resource Center, Boston, MA) | 50mg/kg (days −1, 0, 4, 7, 14, and weekly) (target level >1000μg/mL) |

| Rapamycin (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) | 0.01mg/kgx2/day (target 8–12ng/ml) (from day −3) |

| Methylprednisolone (MP) (Astellas, Deerfield, IL) | 5mg/kg/day tapering to 0.25mg/kg/day |

| Anti-inflammatory | |

| Tocilizumab (IL-6R blockade) (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) | 10mg/kg (days −1, 7, 14, and every 2 weeks) |

| Etanercept (TNF-α antagonist) (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) | 0.5mg/kg (days 0, 3, 7, 10) |

| Adjunctive: | |

| Aspirin (Bayer, Deland, FL) | 40mg p.o. (alternate days) |

| Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Eisai, Woodcliff Lake, NJ) | 700 IU/day s.c |

| Famotidine (APP Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL) | 0.25mg/kg/day x2 (days −5 to 14) |

| Erythropoietin (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) | 2000U (twice weekly) |

| Ganciclovir (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) | 5mg/kg/day i.v |

| Valganciclovir (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) | 15mg/kg/day p.o |

All animal care was in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Research Council (8th edition, revised 2011), was conducted in an AAALACi-accredited facility. Protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgical procedures

Anesthesia, intravascular catheter placement in baboons, kidney excision in pigs, and life-supporting pig kidney transplantation in baboons have been described previously.6,16 In the two Group A baboons, open needle biopsies of the graft were performed at 4 and 7 months after transplantation in one baboon (B17315) and at 6 months in the other (B17615). Ureteric stents (4.8F), placed at the time of the transplants, were removed when renal biopsy was carried out. Furthermore, both baboons developed partial strictures of the pig ureter (resulting in the development of moderate hydronephrosis) requiring corrective surgery at 6 (B17615) and 7 (B17315) months, respectively.

Immunosuppressive and supportive therapy

All baboons received identical therapy, with the exception that one in each group received two doses of cobra venom factor and one did not (Table 2). Anti-CD40mAb (2C10R4, a chimeric rhesus IgG4) was provided by the NIH NHP Reagent Resource.17 We gave erythropoietin throughout the post-transplant course (mainly to compensate for regular blood withdrawals) (Table 2). Erythropoietin also has some immunosuppressive effect which may be beneficial.18–20

Monitoring of recipient baboons

Blood cell counts, chemistry (kidney and liver function), C-reactive protein (CRP), free triiodothyronine (fT3), and coagulation parameters were measured throughout the period of follow-up, as previously described. 7,21–23 Blood cultures were performed whenever indicated. Anti-CD40mAb and rapamycin levels were carried out by MassBiologics and the UPMC Central Laboratory, respectively, and the dosages were based on the current levels or on previous studies by us and others.7,24,25 The pig kidney and ureteric grafts were monitored regularly (every 2 or 4 weeks) by ultrasound (for size and blood flow). Immunological monitoring has been described previously,26 and included (i) flow cytometry to monitor T and B cell numbers (to determine the effect of anti-thymocyte globulin and anti-CD20mAb), and (ii) flow cytometry to monitor binding of xenoreactive anti-nonGal antibodies (IgM and IgG) to GTKO/CD46 pAECs,26

Histopathology and Immunohistopathology of pig kidney grafts

Biopsies of the kidney grafts were obtained at the time of euthanasia (day 12) in Group B, and at approximately 4, 6, and 7 months after transplantation and at necropsy in Group A.27

Statistical analysis

In view of the small number of experiments and the several variables, no statistical analyses were carried out.

RESULTS

Expression of Gal and human transgenes on donor pig AECs

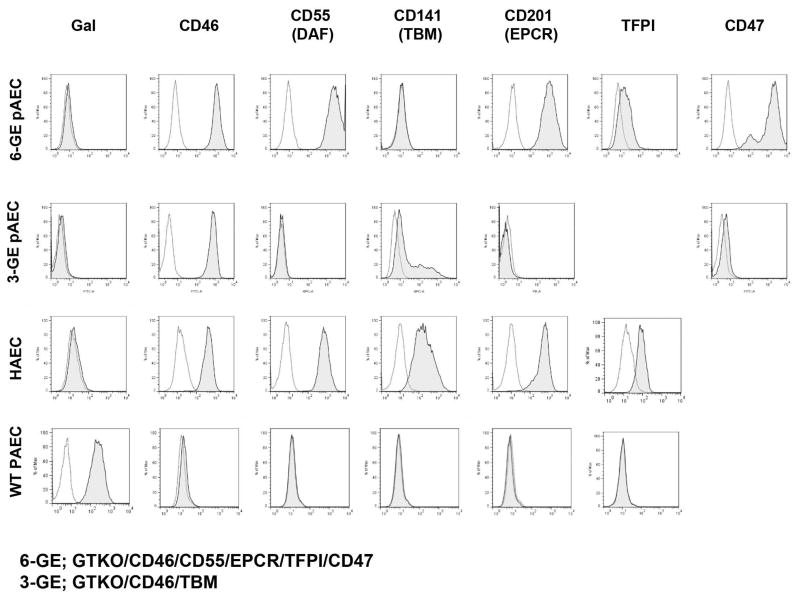

Neither donor pig expressed Gal and both expressed high levels of CD46 on pAECs (Figure 1). High expression of CD55, EPCR, and CD47 on pAECs was documented in the 6-gene pig (Group A), but with a low level of expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) (Figure 1). A moderate level of thrombomodulin was expressed in the 3-gene pig (Group B) (as expected when a porcine thrombomodulin promoter is used) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Expression of human transgenes on donor pAECs by flow cytometry. Gal expression was absent and expression of CD46 was high in both donor pigs. The expression of CD55, EPCR, and CD47 was high on pAECs in the 6-gene donor pig, with some expression of TFPI. In the 3-gene pig, there was moderate expression of thrombomodulin.

Pig kidney graft survival

Both Group A baboons remained healthy for >7–8 months after transplantation, but then succumbed to infectious complications (Table 1). Both Group B baboons required euthanasia on day 12 for consumptive coagulopathy (i.e., thrombocytopenia, falling fibrinogen, spontaneous hemorrhage in one) (Table 1). In Group A, kidney graft function remained excellent until the baboon developed life-threatening complications (see below).

Clinical course and pig kidney graft function

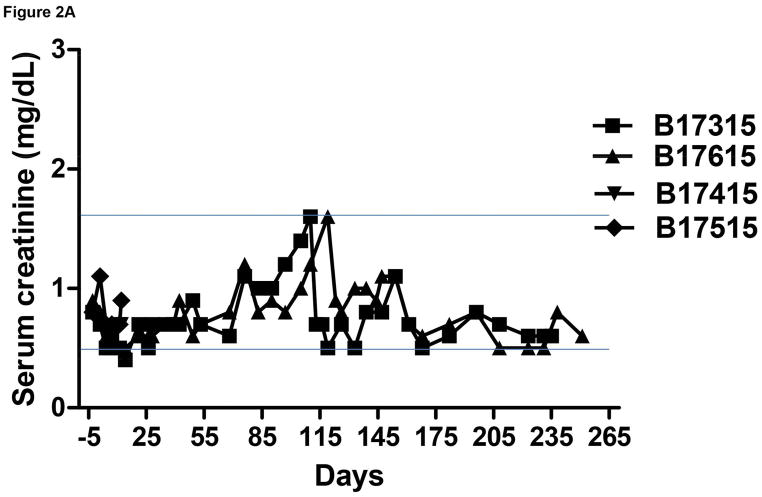

The pig kidney functioned immediately after transplantation in all 4 recipients. Serum creatinine levels normalized quickly with good urine output (approximately 150–200mL/day) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

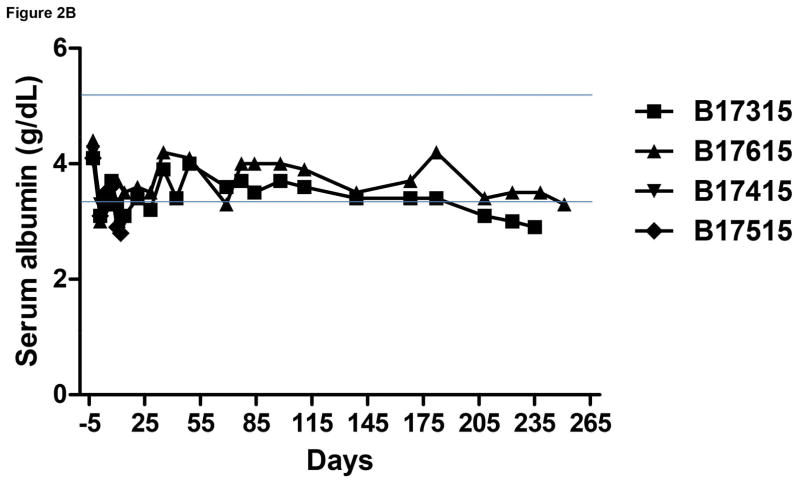

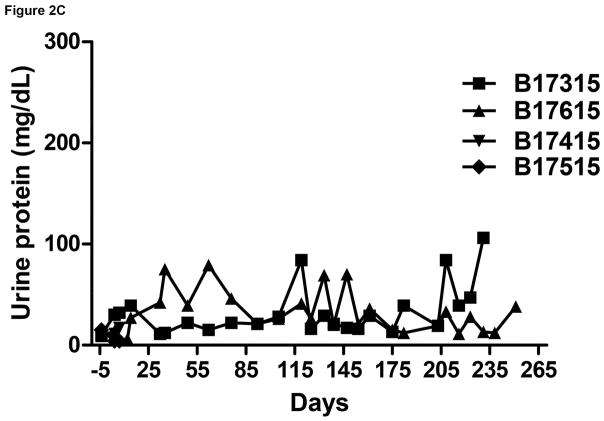

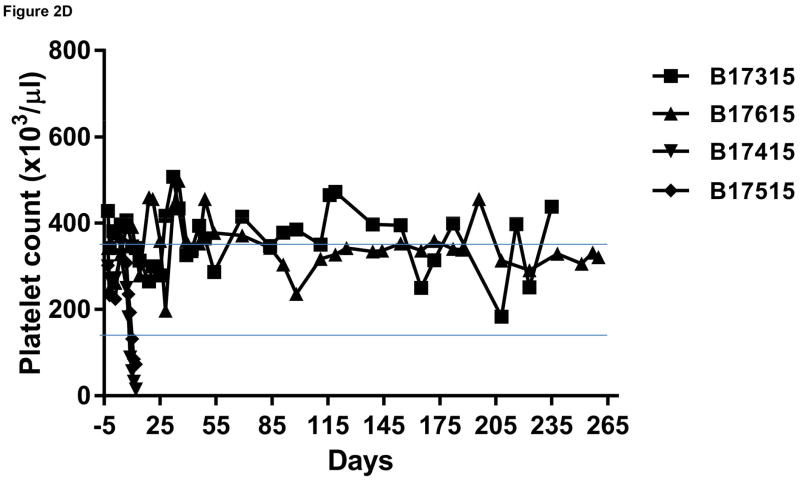

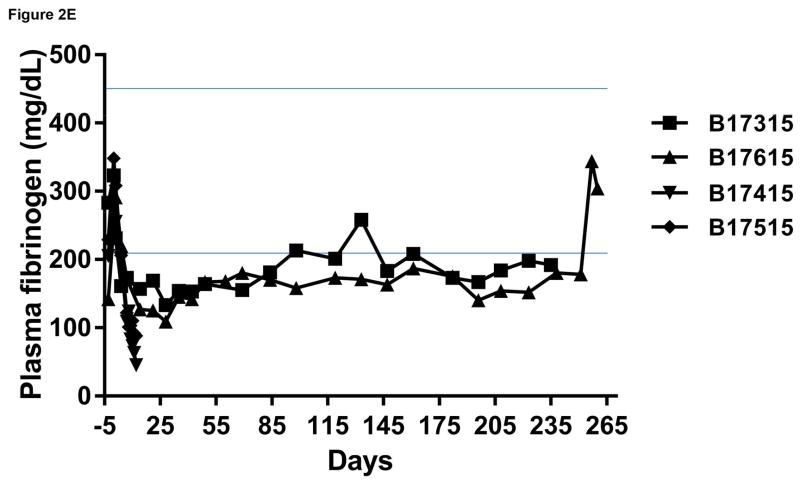

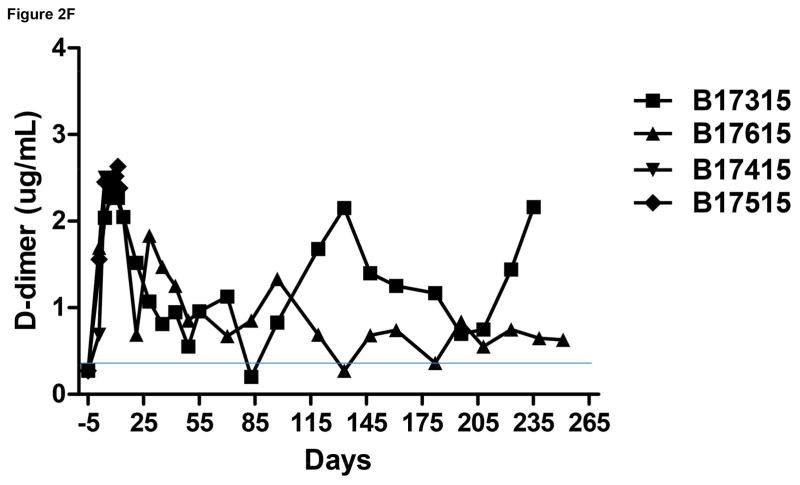

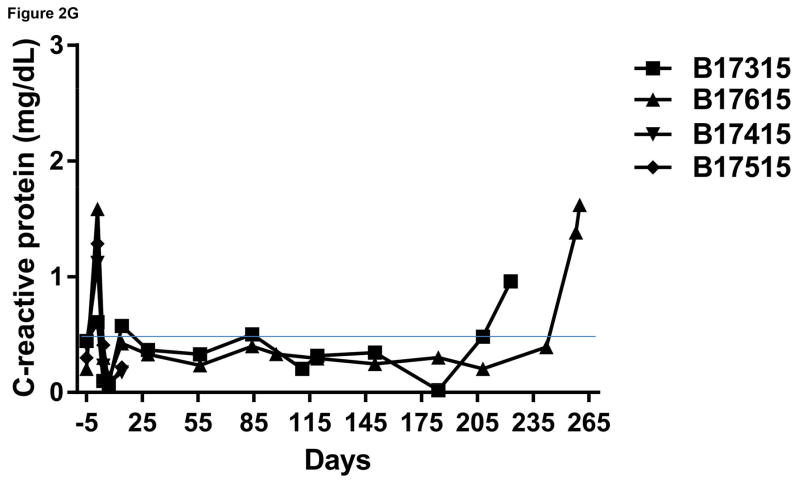

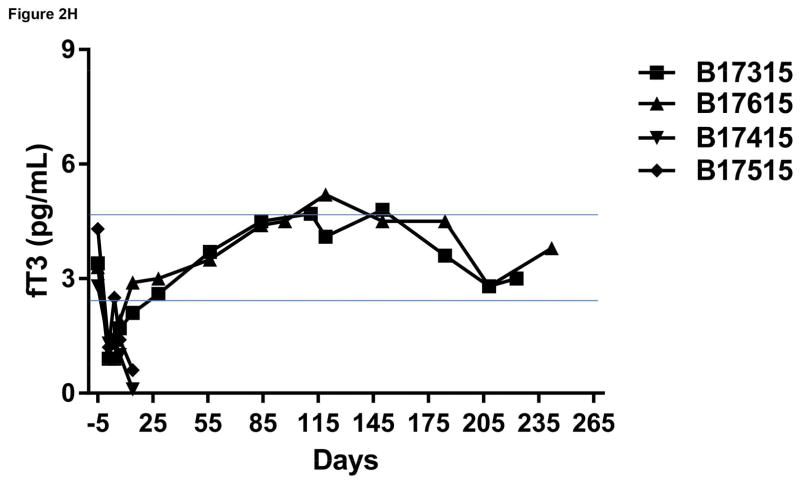

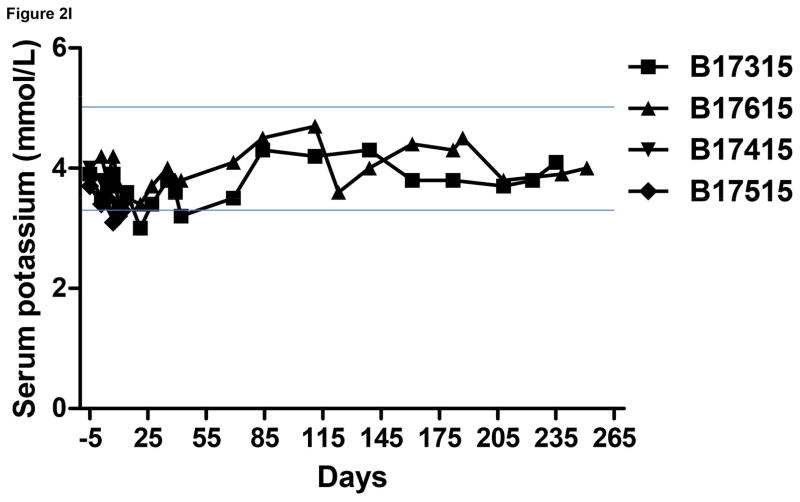

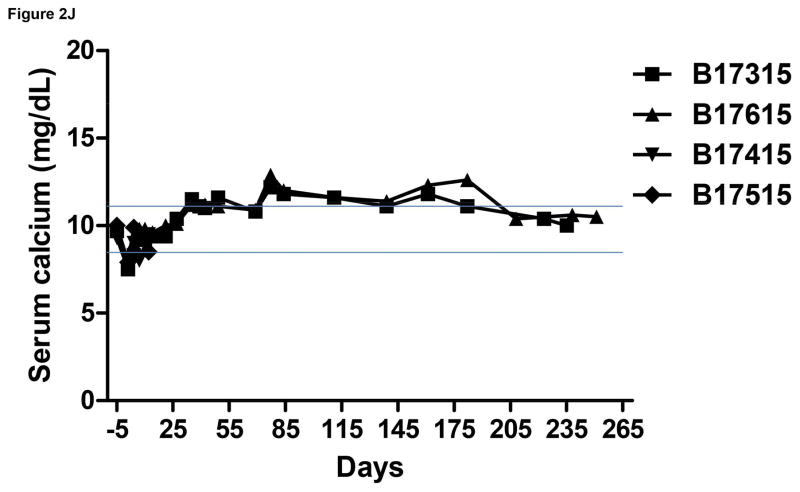

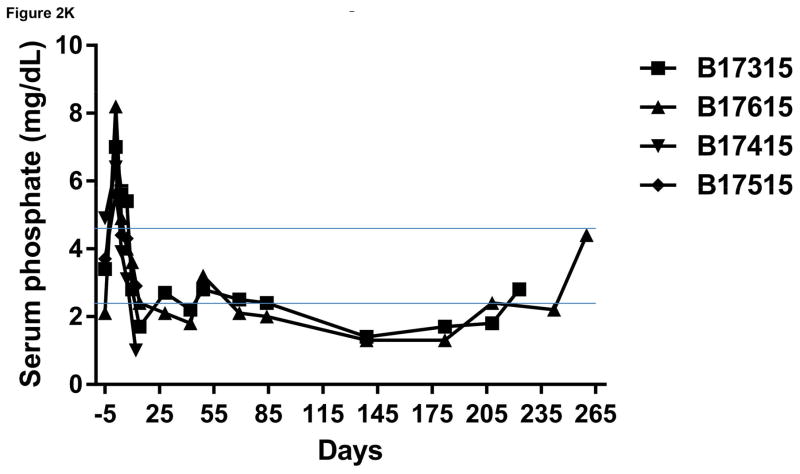

Monitoring of recipient baboon throughout the course of the experiment. (A) serum creatinine; (B) serum albumin; (C) urinary protein; (D) platelet counts; (E) plasma fibrinogen; (F) D-dimer; (G) C-reactive protein; (H) free triiodothyronine (fT3); (I) serum potassium; (J) serum calcium; (K) serum phosphate. The horizontal lines indicate either the upper and lower limits (A, B, D, E, H, I, J, K), or upper limit (F, G), of the equivalent parameters measured in healthy humans.

In both baboons in Group A, the serum creatinine was basically stable and largely within the normal range for >3 months, but thereafter slowly increased even though the baboons were drinking well and passing adequate volumes of urine. Ultrasound studies demonstrated good blood flow through the kidneys. However, increase in size of the kidneys was observed, and also slowly increasing features of hydronephrosis and increasing dilatation of the ureters. No obvious strictures of the ureters could be identified. Serum protein and albumin levels remained basically within the normal ranges (Figure 2B). Proteinuria and albuminuria were generally minimal or modest except after surgical procedures (Figure 2C).

B17315

Because we interpreted the rising serum creatinine as indicating possible rejection or developing thrombotic microangiopathy, we took one of the baboons (B17315) to the operating room to perform an open needle biopsy. During this procedure, the baboon was found to have a low venous pressure and so was administered 400mL of normal saline. The ureter was grossly dilated throughout its course. Although a partial stricture of the distal ureter was suspected (but not associated with the anastomosis of the ureter to the bladder), no surgical procedure was carried out. A needle biopsy of the kidney was taken which showed normal histology.

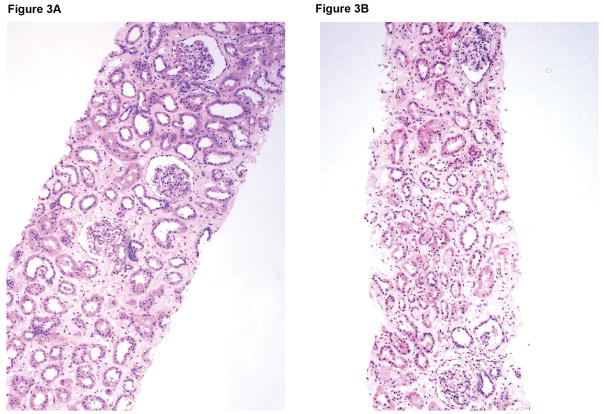

On the following morning, the serum creatinine had returned to the normal range (Figure 2A). Thereafter, we administered normal saline subcutaneously or intravenously x2 weekly until the 7th month, after which it was discontinued. The ultrasound evidence of hydronephrosis increased and so the baboon was explored again after 7 months. The entire length of the ureter was dilated although the partial stricture site was not identified. Therefore, the proximal dilated ureter was re-anastomosed to the bladder (bypass procedure). Another needle biopsy of the kidney was taken which again showed normal histology (Figure 3A). Although the ureter remained dilated, the ultrasound features of hydronephrosis reversed immediately, after which there was some reduction in kidney size (see below).

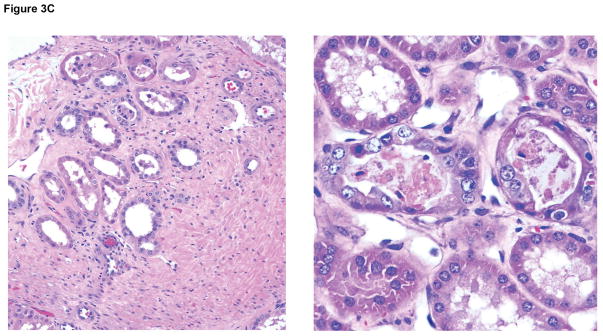

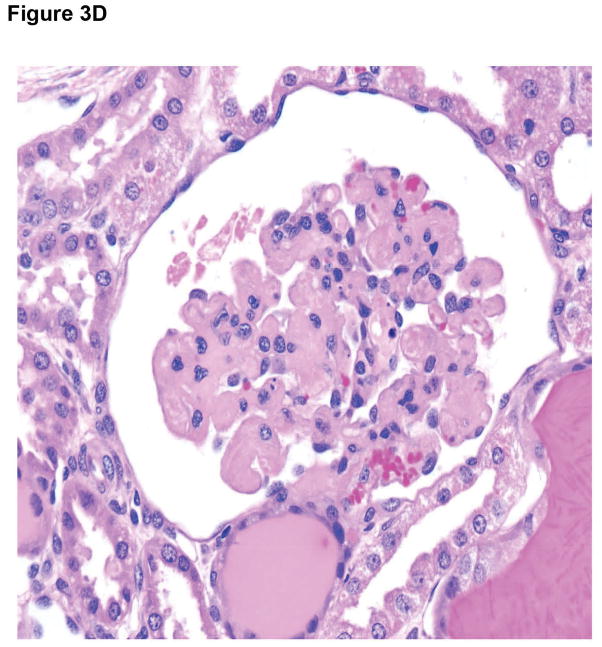

Figure 3.

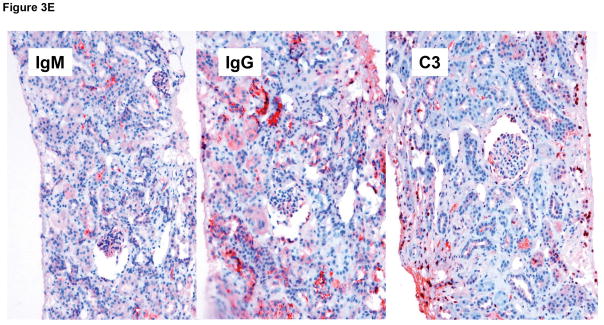

Microscopic appearances of the pig kidney grafts at biopsy at 4 and 7 (A) months (B17315) and at 6 (B) months (B17615) showed no significant abnormalities. At necropsy (at 237 days), the pig kidney in B17615 (C) showed some interstitial fibrosis (left) and mild, patchy acute tubular epithelial cell degeneration in some proximal tubules (right), believed to be secondary to the prolonged hypoxia experienced as a result of the pneumocystis pneumonia. The pig kidney grafts in Group B recipients (D) showed widespread focal hemorrhage and features of thrombotic microangiopathy (multiple occluding thrombi within glomerular capillary loops).

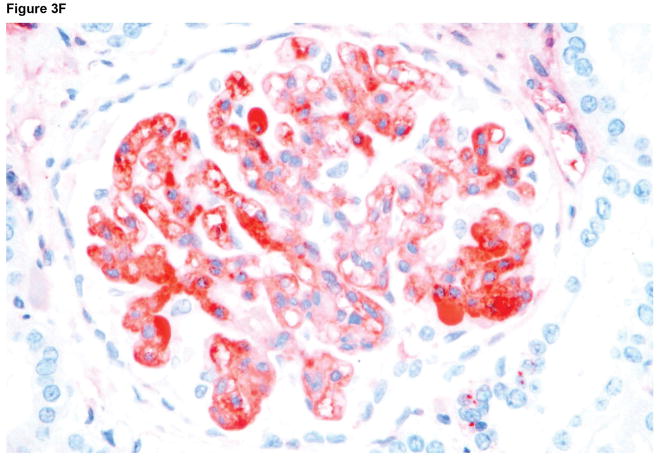

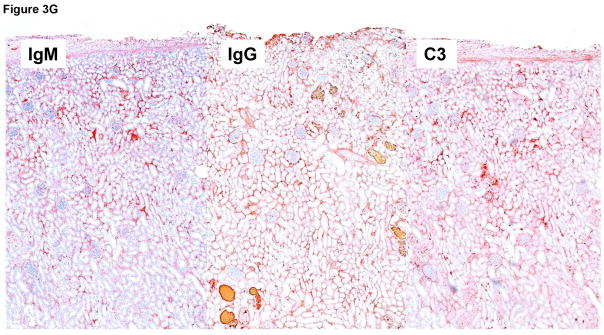

Immunohistochemistry staining of the pig kidney grafts at biopsy at 7 months (B17315) and at 6 months (B17615) in Group A (E), demonstrated non-specific deposition (i.e., not localized to the vascular endothelium) of IgM (left), IgG (center), and complement (C3) (right), suggesting no elicited antibody response. In B17315 at euthanasia (day 237) there was more specific staining for IgM in the glomeruli (F), but no specific staining for IgG or complement (not shown). In Group B at necropsy (G), there was non-specific staining for IgM (left), IgG (center), and complement (right).

Approximately 2 weeks following this (third) surgical procedure (through the same incision), there was a slight partial dehiscence of the abdominal wound, and the baboon became less active. The wound was cleaned daily, but, because a blood culture was negative, systemic antibiotics were not administered. The baboon was found dead on post-transplant day 237. Cultures from the wound and peritoneal fluid grew methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus and enterococcus faecium.

B17615

In view of our experience with this baboon, in the second Group A baboon (B17615), when the serum creatinine rose we administered subcutaneous or intravenous fluids x2 weekly from approximately 3–6 months, by which time ultrasound features of hydronephrosis were increasing. The baboon’s abdomen was explored and a partial stricture was identified in the distal ureter. As in the previous baboon, the proximal ureter was anastomosed to the bladder, thus bypassing the partial stricture. A needle biopsy of the kidney was also taken which showed normal histology (Figure 3B). The ultrasound features of hydronephrosis resolved within 2 weeks, with some reduction in kidney size.

Subsequently, the serum creatinine remained normal without the need for fluid infusions. However, two months after this surgical procedure, the baboon showed features of weight loss and pneumonia. Despite oxygen and systemic antibiotic therapy, the baboon did not improve and was euthanized on humanitarian grounds on day 260. At necropsy, the lungs showed the typical features of a pneumocystis infection (not shown), which unfortunately had not been suspected during life.

Both Group B baboons developed early features of consumptive coagulopathy and required euthanasia on day 12 (see below). The serum creatinine remained within normal limits until the time of euthanasia.

All four baboons underwent necropsy (see below).

Coagulation dysfunction

Platelet counts, fibrinogen levels, D-dimer

No significant changes in platelet count or fibrinogen were observed in the baboons in Group A (Figure 2D), although plasma fibrinogen was maintained at slightly subnormal levels (Figure 2E). In the Group B recipients, after kidney transplantation, thrombocytopenia and a reduction in plasma fibrinogen developed after the first week (Figure 2D,E). A decrease in platelet count to <50,000/μL or <20% baseline was observed within 10days (Figure 2D). After an initial increase associated with the surgical procedure, fibrinogen levels decreased to <100mg/dL or <50% baseline level within 10 days (Figure 2E). One baboon began to bleed from intramuscular and subcutaneous injection sites, and so both baboons were euthanized on humanitarian grounds (on day 12).

In both Group A and B, D-dimer levels initially rose and remained above the normal range, but a variable recovery took place in the recipients in Group A (Figure 2F).

Inflammatory response

C-reactive protein (CRP)

As a result of tocilizumab therapy,23 in Group A, CRP, an indicator of inflammation, remained minimal throughout the post-transplant course, though it rose when infection intervened terminally (at which time tocilizumab was discontinued [day 251]) (Figure 2G). Similarly, in Group B, CRP rose immediately after transplantation, but thereafter recovered and remained minimal (Figure 2G).

Free triiodothyronine (fT3)

Following pig kidney transplantation, there was an immediate rapid fall in fT3 level in all recipients (Figure 2H), which we suggest is a marker of an inflammatory response. 28 Recovery of fT3 within 7 days was seen in Group A, and it remained in the normal range throughout follow-up. In contrast, in Group B, no recovery was seen and fT3 tended to fall as consumptive coagulopathy developed (Figure 2H).

Immunological monitoring

WBC, lymphocyte, T and B cell counts

In all baboons, after ATG on day −3 and anti-CD20mAb on day −2, the WBC count remained low (+/−2,000/μl) throughout most of the period of follow-up (not shown). The total lymphocyte count remained consistently at 200–300/μl (not shown). A profound depletion of T cells was observed. CD3+T cell counts were generally maintained <500/mm3, with CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers frequently less than half of this. After anti-CD20mAb on day −2, B cell subsets were also depleted dramatically and remained almost undetectable throughout the period of follow-up (not shown).

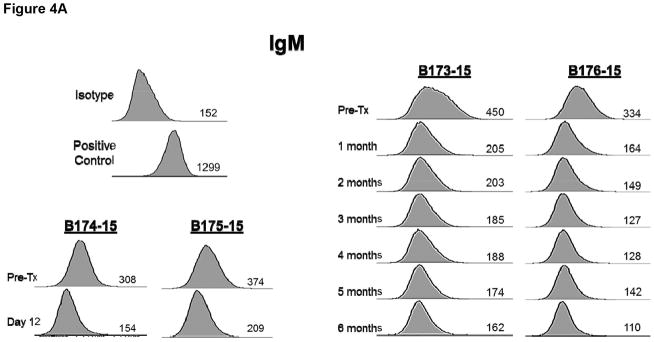

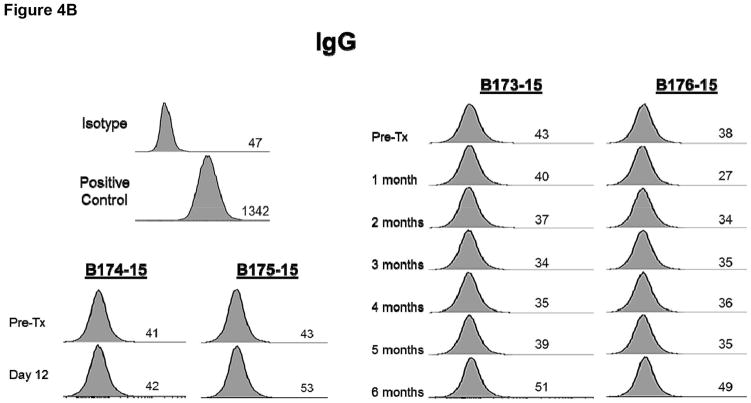

Anti-pig (nonGal) antibodies

There was no increase in xenoreactive IgM in any baboon (Figure 4A) and there was no IgG sensitization to nonGal antigens expressed on the pAECs, indicating no sensitization to nonGal antigens (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Anti-pig nonGal IgM (A) and IgG (B) levels in the recipient baboons (determined by flow cytometry) throughout the post-transplant course.

Monitoring of immunosuppressive drug levels

In Group A baboons, anti-CD40mAb (2C10R4) levels remained high (generally >2,000ug/mL) throughout the first 6 months (not shown). (Later levels are not yet available.) Serum anti-Ig antibody levels remained <10, indicating that no antibody had developed against the 2C10R4 mAb. Serum levels of rapamycin remained largely in the desired range of 8–12ng/mL although there were several spontaneous variations in both Group A baboons (not shown).

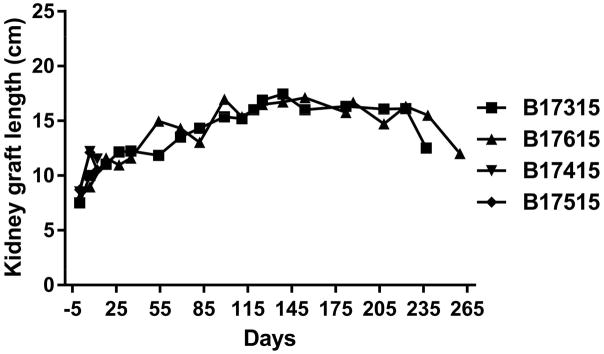

Pig kidney graft size

In the Group A baboons, the pig kidney grafts increased markedly in length during the first 2–4 weeks (but not greatly in width or thickness), but subsequent growth slowed and plateaued (Figure 5). After relief of the hydronephrosis, there was some reduction in pig kidney size.

Figure 5.

Increases in the lengths of the two Group A pig kidneys determined by ultrasound or direct measurement (at operation).

Histopathology and immunohistopathology of pig kidneys and ureters

In Group A, in the biopsies taken at 4, 6, and 7 months after transplantation, there were no features suggestive of antibody-mediated or acute cellular rejection (Figure 3A,B). There were also no features of rejection or inflammation in the ureteric biopsies taken on days 187 and 223 (not shown). At necropsy on days 237 and 260, respectively, there was a mild-moderate increase in vacuolization within the urothelial layer, but no features of rejection or inflammation in the kidneys or ureters, though in B17615 there was some interstitial fibrosis (left) and mild, patchy acute tubular epithelial cell degeneration in some proximal tubules (right), believed to be secondary to the prolonged hypoxia experienced as a result of the pneumocystis pneumonia (Figure 3C). However, there were no significant histopathological abnormalities in any of the native organs.

In Group B, the pig kidney grafts at necropsy on day 12 exhibited focal areas of thrombosis and hemorrhage (Figures 3D). There was also peri-ureteral thrombus and patchy of focally-extensive hemorrhage (not shown).

Immunohistochemistry indicated non-specific deposition of IgM, IgG, and complement (C3) in the Group A grafts on biopsies and at necropsy (Figure 3E), although in B17315 there was more specific IgM staining of the glomerular vascular endothelium at necropsy (Figure 3F). As this specific IgM staining was not present in the biopsy taken only 12 days earlier, we suggest it was related to an inflammatory state associated with the development of an infectious peritonitis. In Group B at necropsy on day 12, only nonspecific staining was seen (Figure 3G).

Physiological observations in the baboons of Group A

In Group A baboons, serum potassium remained within normal limits (Figure 2I), which is consistent with previous reports.5,29,30

Serum calcium was also maintained at normal levels for about 2 months, but gradually increased to a level slightly higher than normal (Figure 2J), which is a similar finding to other reports.5 Serum phosphate rose immediately after transplantation, but thereafter slowly fell, and remained in the low-to-normal range (Figure 2K), as reported previously. 5,29,30

DISCUSSION

We carried out 4 kidney transplants using identical immunosuppressive/adjunctive therapy, identical surgical teams, and identical post-transplant management, but with 2 different genetically-engineered pigs as sources of the kidneys. The only difference in the experiments, therefore, was the genetic-engineering of the source pigs. Although the number of experiments is small (with 2 in each group), we suggest we can draw the following tentative conclusions.

The survival of the Group A baboons progressed for >7 months in the absence of features of thrombotic microangiopathy or consumptive coagulopathy, without the need for a continuous i.v. infusion of heparin (which potentially reduces both thrombosis and inflammation). The absence of the need for heparin is important as prolonged i.v. heparin administration will clearly be impractical clinically. The excellent results following pig heterotopic heart transplantation obtained by the NHLBI group (with graft function in one baboon for >2 years) were achieved using continuous i.v. heparin therapy.31 We suggest that the present encouraging results provide a significant advance in management in this respect.

Proteinuria was not problematic, with no requirement to boost and maintain the serum albumin by the administration of human albumin. This is in contrast to almost all previous studies,4,29,30,32,33 with the exception of our own recent experience 7 and that of Higginbotham et al.5 This suggests that the proteinuria reported previously was associated with a low-grade immune response, e.g., activation of the vascular endothelium by anti-pig antibodies or complement, rather than from physiological incompatibilities between pig and primate.

-

The baboons did not become sensitized to pig antigens, suggesting that the immunosuppressive regimen was successful in the absence of an anti-CD154mAb (which we avoided in view of its thrombogenic effect.34–36

The anti-CD40mAb that formed the basis of the immunosuppressive regimen (2C10R4) was clearly efficient in preventing an adaptive immune response, as we and others have demonstrated previously in kidney, heart, and artery patch transplant models.7,25,31,37–39 The serum levels achieved in the present study were higher than those documented in earlier reports,31 and some reduction in dosage may be possible without detrimental effect. The higher levels documented in the present study may possibly be associated with the concomitant administration of the IL-6R antagonist, tocilizumab, though we have no hard evidence for this. Whether a similar excellent outcome could be achieved with conventional immunosuppressive therapy, e.g., a tacrolimus-based regimen, remains uncertain (though in previous studies the trough levels that proved necessary were extremely high,40,41 which would be detrimental to kidney graft function).

The expression of a modest level of thrombomodulin alone in the graft (as in Group B) on a GTKO/CD46 background may be insufficient to prevent the development of thrombotic microangiopathy and/or consumptive coagulopathy (although we cannot exclude that the absence of expression of CD55 may also be important). This observation is in contrast to the results obtained after heterotopic heart transplantation in the pig-to-baboon model, where hearts from GTKO/CD46/thrombomodulin pigs functioned for months or even years.25,31 However, we and others have observed differences between survival of pig hearts and kidneys,16,42,43 and these have been confirmed on a molecular level by Knosalla, et al.44 Our experience is that kidney transplantation is much more readily associated with an early consumptive coagulopathy whereas heart transplantation is associated with a more gradual development of thrombotic microangiopathy with only the very late development of consumptive coagulopathy. It is possible that, if the expression of thrombomodulin had been stronger, the grafts in the GroupB baboons would have survived longer.

Based on the results in Group A and our previous experience of one baboon in which the kidney graft (that expressed EPCR and CD55, but not TFPI) functioned relatively well for >4 months until infection developed,7 the expression of EPCR in the graft appears to be beneficial or may even be essential. A beneficial effect of EPCR has also been reported by the University of Maryland group in their short-term organ perfusion model where pig lungs are perfused with human blood.45

Induction with cobra venom factor (to deplete complement) is unnecessary (as the outcome within both Group A and Group B was identical whether cobra venom factor was administered or not).

In the Group A recipients (as in our previous case report 7), a marked increase in size of the kidney graft was observed during the first 2–4 weeks post-transplantation. This was not a result of rejection, when interstitial hemorrhage, thrombosis and cellular infiltrates might increase graft weight and size. The cause remains uncertain, but the partial obstruction of the ureter, resulting in increasing hydronephrosis, may well have played a role. Alternatively, it could be associated with compensatory enlargement when one immature kidney takes the place of two mature kidneys excised from an 8kg baboon. Relatively rapid growth in kidney allografts takes place when kidneys from infants or children are transplanted into adult recipients.46,47 However, it is possible that residual pig growth hormone is still present in the graft that leads to an initial increase in size as it would if the kidney had remained in the juvenile (rapidly-growing) pig; rapid growth ceases when pig growth hormone is depleted. An early increase in kidney graft size was reported previously by Soin et al 48 and was seen by us in our previous report (in which, however, hydronephrosis also developed),7 but has not been commented on by others.5,32,43 Nor has rapid growth been reported after heterotopic pig heart transplantation in baboons.25,39,49 Further investigation of this observation is warranted.

The development of infectious complications in the two Group A baboons [as in our recent previous experience 7] is a reminder of the complications that can result in subjects after relatively long-term immunosuppressive therapy. However, we would suggest that both complications would have been much easier to prevent and/or treat in patients under hospital conditions than in baboons in an experimental laboratory. For example, in clinical practice, pneumocystis can be readily prevented or diagnosed and treated. To our knoweldge, no baboon in which a pig kidney or heart graft has functioned well for >6 months has lost the graft from an immune response unless the immunosuppressive therapy has been discontinued or greatly reduced.7,39,49 In view of the great difficulty of managing immunosuppressed nonhuman primates, we suggest that 6-month follow-up is sufficient to determine the success of a pig heart or kidney xenotransplant.

Several questions related to the study remain unanswered.

-

What is the cause of the ureteric partial strictures that developed?

Both of the Group A baboons presented with rising serum creatinine levels between 3–4 months after kidney transplantation, as did the baboon we reported previously.3 Both baboons were producing 150–200mL of urine each day, and so we initially thought this may be a result of a pathophysiological disturbance, e.g., the baboons were unaware when they were becoming dehydrated. Subsequently, the serum creatinine could be maintained within the normal range by x2 weekly infusions of fluid. However, throughout the first 3 months, there was ultrasound evidence of increasing dilatation of the ureter throughout most of its course and of hydronephrosis developing in the kidney graft. Exploration of the two baboons at 4 and 7 months (B17315) and at 6 months (B17615) indicated a grossly dilated ureter with a partial stricture of the distal ureter (though not related to the site of anastomosis to the bladder). Bypass of the ureteric stricture resulted in correction of the features of hydronephrosis and maintenance of a normal serum creatinine level without the need for extra fluid administration. The cause of the partial stricture remains uncertain but ischemic injury of the distal ureter is a possibility. (In collaboration with Dr Angus Thomson, we have carried out 19 kidney allotransplants in monkeys [approximate weight 5kg] without encountering this complication,50 suggesting that it could have an immune/inflammatory basis.) We did not investigate whether BK virus might be a causative factor because (i) post-transplant strictures are rarely viral, (ii) to our knowledge cross-species tropism/pathogenicity of BK virus is unknown, and (iii) of a lack of species-specificity of the assays available.

-

Is induction therapy with an anti-CD20mAb essential or even beneficial?

Both McGregor et al. (using a conventional immunosuppressive regimen) and Mohiuddin et al. (using a T cell costimulation blockade-based regimen) provided data to suggest that a full peri-transplant course of anti-CD20mAb (20mg/kg x4) improved outcome.41,49 We, however, reported a high incidence of infectious complications when an anti-CD20mAb (20mg/kg x1) was administered,25 and therefore elected to administer only a single half-dose (10mg/kg) on day −2. We were also influenced by the fact that there has been a trend for reduced doses to be administered to patients receiving ABO-incompatible allografts in recent years.51,52 We remain unconvinced that even a single small dose is necessary, and we plan to omit it in some future experiments.

-

Is anti-inflammatory therapy in the form of IL-6R blockade and/or TNF-α blockade essential or even beneficial?

We have reported evidence for a prolonged inflammatory response to a pig xenograft.23,53,37 We suggest that suppressing the inflammatory response may well facilitate the role of the immunosuppressive therapy and reduce the risk of both rejection and coagulation dysfunction.54–56 We have data suggesting that the cytokine, interleukin-6 (IL-6), is playing a role, and that IL-6R blockade reduces this response.23 IL-6R blockade does not have an inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation in vitro (Iwase H, unpublished data). We have no personal data that tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is important, but its perceived benefit in islet allo- and xeno-transplantation 57–59 persuaded us to incorporate a short course in our protocol. It has also been demonstrated to be protective against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury.60

In the present study, CRP (one of the indicators of an inflammatory response) was minimal under the administration of IL-6R blockade (except transiently after the operative procedures), which correlated with our previous studies.23,53 Following xenotransplantation, we have observed a rapid decline of fT3 within hours. The level of fT3 recovered slowly to only the low-normal range. A persisting low fT3 may be related to an ongoing inflammatory state.28 However, the addition of IL-6R blockade appeared to be associated with a quicker recovery of fT3 and a higher sustained level,28 which was also observed in the long-surviving recipients in Group A. In contrast, when consumptive coagulopathy was developing in the Group B recipients, almost no recovery of fT3 was observed, which is consistent with our previous observations.28

We suggest that D-dimer may also be an indicator of an inflammatory response rather than of a consumptive coagulopathy.25,23 Variable, but slightly higher than normal D-dimer levels were observed in the long-surviving recipients in Group A (Figure 2F).

-

Does the species of the recipient NHP affect outcome?

As cited above, Higginbotham et al. have reported transplantation of GTKO/CD55 pig kidneys (with no transgenic expression of human coagulation-regulatory proteins) in two rhesus monkeys selected for low anti-pig antibody levels that survived for >125 days,5 with one monkey surviving for 10 months without developing features of thrombotic microangiopathy or consumptive coagulopathy until terminally (Adams A, personal communication). In view of our present and previous data, this was a surprising result. Furthermore, these excellent outcomes were obtained with an anti-CD154mAb-based regimen in the absence of any anticoagulation (i.e., no continuous intravenous heparin). Because of the known thrombogenic effects of anti-CD154mAbs,34 particularly in the xenotransplantation setting,36,42,35 it is surprising that coagulation dysfunction did not develop earlier.

This may have been associated with the fact that the monkeys were selected for very low anti-pig antibody levels, the hypothesis being that, in the absence of antibody, no endothelial activation occurs, thus abrogating complement activation and coagulation dysregulation (as put forward independently by several investigators [reviewed in 61], and Tector AJ, personal communication). However, in the present study, despite the fact that all 4 baboons were selected for low anti-pig antibody levels, the results were markedly different between the two groups.

Only slight differences in anti-pig antibody levels between baboons and monkeys have been documented, e.g., cynomolgus monkeys have rather higher levels of anti-nonGal antibodies than baboons,62 whereas anti-Gal antibody levels are particularly low in rhesus monkeys.63 It is possible, however, that there are other immunological and/or physiological differences between rhesus monkeys and baboons that account for the differences in outcome. We would therefore recommend that, before any clinical trials of pig kidney transplantation are undertaken, experiments are carried out in both rhesus monkey and baboon recipients.

In conclusion, we are encouraged by the prolonged survival of two of the baboons with life-supporting pig kidney grafts. We believe that a specific phenotype of the genetically-engineered pig in combination with an effective costimulation blockade-based immunosuppressive regimen and anti-inflammatory therapy may all have contributed to the outcome. The results encourage us that clinical xenotransplantation will become a reality in the near future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Keith Reimann for providing anti-CD40mAb from the NHP Reagent Resource (contract HHSN2722001300031C). Work on xenotransplantation in the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute of the University of Pittsburgh is, or has been, supported in part by NIH grants #U19 AI090959, #U01 AI068642, and # R21 A1074844, and by Sponsored Research Agreements between the University of Pittsburgh and Revivicor, Inc., Blacksburg, VA. The baboon used in the study was from the Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center, Division of Animal Resources, which is supported by NIH P40 sponsored grant RR012317-09.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AECs

aortic endothelial cells

- EPCR

endothelial protein C receptor

- GTKO

α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout

- IL-6R

interleukin-6 receptor

- NHP

nonhuman primate

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

David Ayares and Carol Phelps are employees of Revivicor, Inc. No other author has a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cooper DK, Satyananda V, Ekser B, et al. Progress in pig-to-nonhuman primate transplantation models (1998–2013): a comprehensive review of the literature. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:397–419. doi: 10.1111/xen.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambrigts D, Sachs DH, Cooper DK. Discordant organ xenotransplantation in primates: world experience and current status. Transplantation. 1998;66:547–561. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwase H, Kobayashi T. Current status of pig kidney xenotransplantation. Int J Surg. 2015;23:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldan N, Rigotti P, Calabrese F, et al. Ureteral stenosis in HDAF pig-to-primate renal xenotransplantation: a phenomenon related to immunological events? Am J Transplant. 2004;4:475–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higginbotham L, Mathews D, Breeden CA, et al. Pre-transplant antibody screening and anti-CD154 costimulation blockade promote long-term xenograft survival in a pig-to-primate kidney transplant model. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:221–230. doi: 10.1111/xen.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CC, Ezzelarab M, Shapiro R, et al. Recipient tissue factor expression is associated with consumptive coagulopathy in pig-to-primate kidney xenotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1556–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwase H, Liu H, Wijkstrom M, et al. Pig kidney graft survival in a baboon for 136 days: longest life-supporting organ graft survival to date. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:302–309. doi: 10.1111/xen.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H, Iwase H, Wijkstrom M, et al. Myroides infection in a baboon after prolonged pig kidney graft survival. Transplantation Direct. 2015;1 doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayares D, Vaught T, Ball S, et al. Genetic engineering of source pigs for xenotransplantation: progress and prospects. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:361. (Abstract 408) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper DK, Ekser B, Burlak C, et al. Clinical lung xenotransplantation--what donor genetic modifications may be necessary? Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:144–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2012.00708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tena A, Leonard D, Tasaki M, et al. Initial evidence for functional immune modulation in primate recipients of porcine skin grafts following conditioning with human CD47 transgeneic pig hematopoietic stem cells. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20 (Abstract 274) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boksa M, Zeyland J, Slomski R, Lipinski D. Immune modulation in xenotransplantation. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2015;63:181–192. doi: 10.1007/s00005-014-0317-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klymiuk N, Wuensch A, Kurome M, et al. GalT-KO/CD46/hTM triple-transgenic donor animals for pig-to-baboon heart transplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:271. (Abstract #126) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wuensch A, Baehr A, Bongoni AK, et al. Regulatory sequences of the porcine THBD gene facilitate endothelial-specific expression of bioactive human thrombomodulin in single- and multitransgenic pigs. Transplantation. 2014;97:138–147. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182a95cbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou H, Iwase H, Wolf RF, et al. Are there advantages in the use of specific pathogen-free baboons in pig organ xenotransplantation models? Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:287–290. doi: 10.1111/xen.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezzelarab M, Garcia B, Azimzadeh A, et al. The innate immune response and activation of coagulation in alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout xenograft recipients. Transplantation. 2009;87:805–812. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318199c34f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowe M, Badell IR, Thompson P, et al. A novel monoclonal antibody to CD40 prolongs islet allograft survival. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:2079–2087. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cravedi P, Manrique J, Hanlon KE, et al. Immunosuppressive effects of erythropoietin on human alloreactive T cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2003–2015. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013090945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez F, Pallet N. When erythropoietin meddles in immune affairs. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1887–1889. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe M, Lundgren T, Saito Y, et al. A Nonhematopoietic Erythropoietin Analogue, ARA 290, Inhibits Macrophage Activation and Prevents Damage to Transplanted Islets. Transplantation. 2016;100:554–562. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekser B, Bianchi J, Ball S, et al. Comparison of hematologic, biochemical, and coagulation parameters in alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs, wild-type pigs, and four primate species. Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:342–354. doi: 10.1111/xen.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwase H, Ekser B, Satyananda V, Ezzelarab M, Cooper DK. Plasma free triiodothyronine (fT3) levels in baboons undergoing pig organ transplantation: relevance to early recovery of organ function. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:582–583. doi: 10.1111/xen.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwase H, Ekser B, Zhou H, et al. Further evidence for a sustained systemic inflammatory response in xenograft recipients (SIXR) Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:399–405. doi: 10.1111/xen.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson TC, Trambley J, Odom K, et al. Anti-CD40 therapy extends renal allograft survival in rhesus macaques. Transplantation. 2002;74:933–940. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwase H, Ekser B, Satyananda V, et al. Pig-to-baboon heterotopic heart transplantation--exploratory preliminary experience with pigs transgenic for human thrombomodulin and comparison of three costimulation blockade-based regimens. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:211–220. doi: 10.1111/xen.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ezzelarab M, Hara H, Busch J, et al. Antibodies directed to pig non-Gal antigens in naive and sensitized baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:400–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekser B, Klein E, He J, et al. Genetically-engineered pig-to-baboon liver xenotransplantation: histopathology of xenografts and native organs. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwase H, Ekser B, Hara H, et al. Thyroid hormone: relevance to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2016;23:293–299. doi: 10.1111/xen.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soin B, Smith KG, Zaidi A, et al. Physiological aspects of pig-to-primate renal xenotransplantation. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1592–1597. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibrahim Z, Busch J, Awwad M, et al. Selected physiologic compatibilities and incompatibilities between human and porcine organ systems. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:488–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, et al. Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long-term survival of GTKO.hCD46.hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11138. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cozzi E, Vial C, Ostlie D, et al. Maintenance triple immunosuppression with cyclosporin A, mycophenolate sodium and steroids allows prolonged survival of primate recipients of hDAF porcine renal xenografts. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10:300–310. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamada K, Yazawa K, Shimizu A, et al. Marked prolongation of porcine renal xenograft survival in baboons through the use of alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout donors and the cotransplantation of vascularized thymic tissue. Nat Med. 2005;11:32–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawai T, Andrews D, Colvin RB, Sachs DH, Cosimi AB. Thromboembolic complications after treatment with monoclonal antibody against CD40 ligand. Nat Med. 2000;6:114. doi: 10.1038/72162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knosalla C, Gollackner B, Cooper DK. Anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody and thromboembolism revisted. Transplantation. 2002;74:416–417. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200208150-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ezzelarab MB, Ekser B, Echeverri G, et al. Costimulation blockade in pig artery patch xenotransplantation - a simple model to monitor the adaptive immune response in nonhuman primates. Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2012.00711.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ezzelarab MB, Ekser B, Azimzadeh A, et al. Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients precedes activation of coagulation. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:32–47. doi: 10.1111/xen.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, et al. Role of anti-CD40 antibody-mediated costimulation blockade on non-Gal antibody production and heterotopic cardiac xenograft survival in a GTKO.hCD46Tg pig-to-baboon model. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:35–45. doi: 10.1111/xen.12066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, et al. One-year heterotopic cardiac xenograft survival in a pig to baboon model. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:488–489. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Byrne GW, Du Z, Sun Z, Asmann YW, Mcgregor CG. Changes in cardiac gene expression after pig-to-primate orthotopic xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:14–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGregor CG, Ricci D, Miyagi N, et al. Human CD55 expression blocks hyperacute rejection and restricts complement activation in Gal knockout cardiac xenografts. Transplantation. 2012;93:686–692. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182472850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuwaki K, Knosalla C, Dor FJ, et al. Suppression of natural and elicited antibodies in pig-to-baboon heart transplantation using a human anti-human CD154 mAb-based regimen. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:363–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamada K, Tasaki M, Sekijima M, et al. Porcine cytomegalovirus infection is associated with early rejection of kidney grafts in a pig to baboon xenotransplantation model. Transplantation. 2014;98:411–418. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knosalla C, Yazawa K, Behdad A, et al. Renal and cardiac endothelial heterogeneity impact acute vascular rejection in pig-to-baboon xenotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1006–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris DG, Quinn KJ, French BM, et al. Meta-analysis of the independent and cumulative effects of multiple genetic modifications on pig lung xenograft performance during ex vivo perfusion with human blood. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:102–111. doi: 10.1111/xen.12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pape L, Hoppe J, Becker T, et al. Superior long-term graft function and better growth of grafts in children receiving kidneys from paediatric compared with adult donors. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2596–2600. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foss A, Line PD, Brabrand K, Midtvedt K, Hartmann A. A prospective study on size and function of paediatric kidneys (<10 years) transplanted to adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1738–1742. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soin B, Ostlie D, Cozzi E, et al. Growth of porcine kidneys in their native and xenograft environment. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:96–100. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohiuddin MM, Corcoran PC, Singh AK, et al. B-cell depletion extends the survival of GTKO.hCD46Tg pig heart xenografts in baboons for up to 8 months. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ezzelarab MB, Zahorchak AF, Lu L, et al. Regulatory dendritic cell infusion prolongs kidney allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1989–2005. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuchinoue S, Ishii Y, Sawada T, et al. The 5-year outcome of ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation with rituximab induction. Transplantation. 2011;91:853–857. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31820f08e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shin M, Kim SJ. ABO Incompatible Kidney Transplantation-Current Status and Uncertainties. J Transplant. 2011;2011:970421. doi: 10.1155/2011/970421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwase H, Liu H, Gao B, et al. Therapeutic regulation of systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients. Xenotransplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1111/xen.12296. (revised after review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mori DN, Kreisel D, Fullerton JN, Gilroy DW, Goldstein DR. Inflammatory triggers of acute rejection of organ allografts. Immunol Rev. 2014;258:132–144. doi: 10.1111/imr.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ezzelarab MB, Cooper DK. Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients (SIXR): A new paradigm in pig-to-primate xenotransplantation? Int J Surg. 2015;23:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braza F, Brouard S, Chadban S, Goldstein DR. Role of TLRs and DAMPs in allograft inflammation and transplant outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:281–290. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsumoto S, Takita M, Chaussabel D, et al. Improving efficacy of clinical islet transplantation with iodixanol-based islet purification, thymoglobulin induction, and blockage of IL-1beta and TNF-alpha. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:1641–1647. doi: 10.3727/096368910X564058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson P, Badell IR, Lowe M, et al. Islet xenotransplantation using gal-deficient neonatal donors improves engraftment and function. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2593–2602. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takita M, Matsumoto S, Shimoda M, et al. Safety and tolerability of the T-cell depletion protocol coupled with anakinra and etanercept for clinical islet cell transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:E471–484. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagata Y, Fujimoto M, Nakamura K, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha Agent Infliximab and Splenectomy Are Protective Against Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Transplantation. 2016;100:1675–1682. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robson SC, Cooper DK, D’apice AJ. Disordered regulation of coagulation and platelet activation in xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:166–176. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rood PP, Hara H, Ezzelarab M, et al. Preformed antibodies to alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout (GT-KO) pig cells in humans, baboons, and monkeys: implications for xenotransplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3514–3515. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teranishi K, Manez R, Awwad M, Cooper DK. Anti-Gal alpha 1-3Gal IgM and IgG antibody levels in sera of humans and old world non-human primates. Xenotransplantation. 2002;9:148–154. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2002.1o058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]